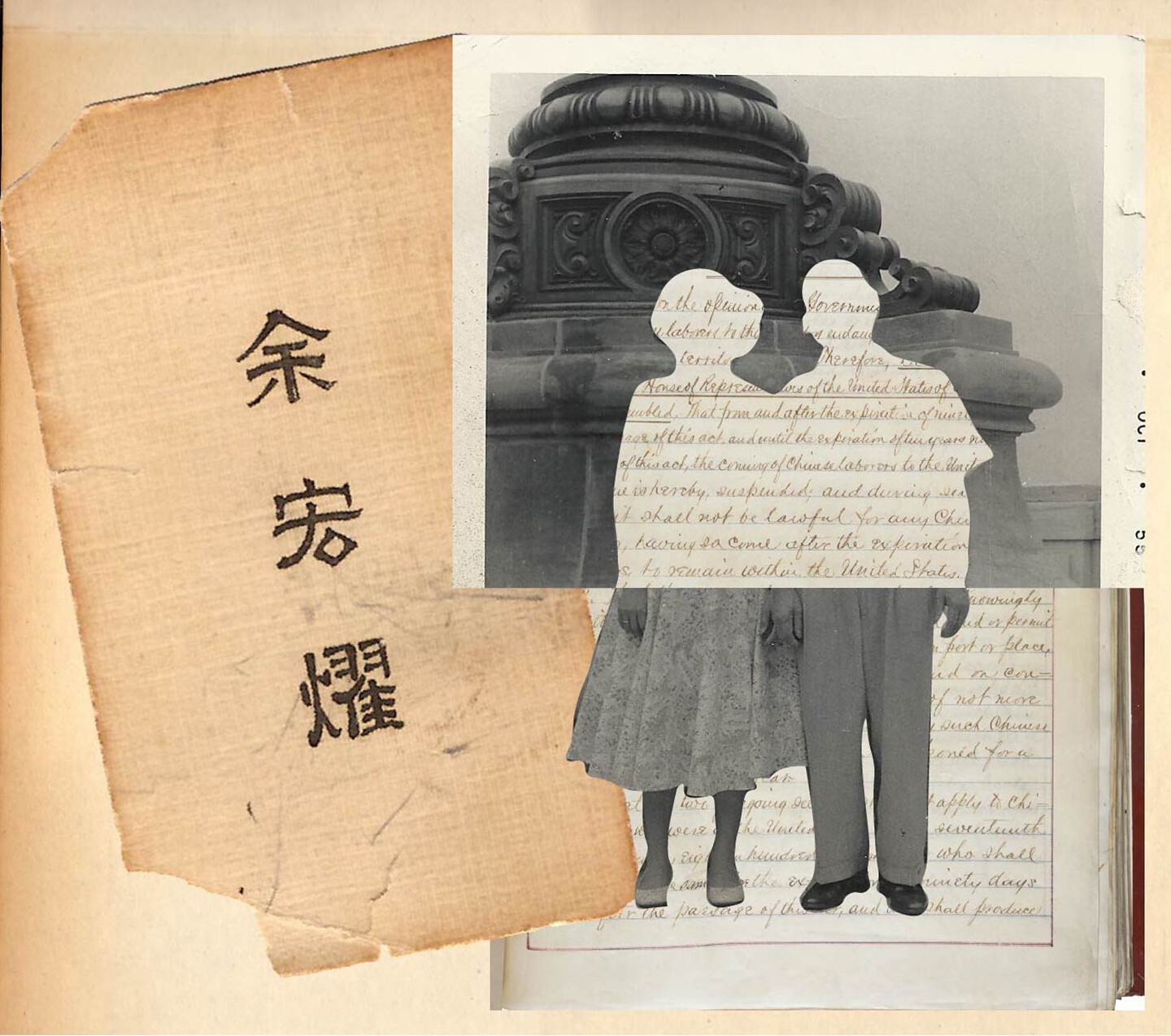

Cultivate Christchurch, the Aotearoa New Zealand based urban farm and youth wellbeing project, has inspired people all over the world with its grounded, place-attentive approach to youth wellbeing in a disaster recovery setting. This conversation is between Bailey Peryman, one of the founders and vision holders of the organization, and Kelly Dombroski, a curious academic who partnered with Cultivate for a nationally funded project on urban wellbeing, and discusses how Cultivate’s work relates to the concepts of survivance and havening. Since it took place, Bailey is now working on his PhD project with Kelly as supervisor via a second nationally-funded urban wellbeing research program.

Kelly Dombroski The first time I visited Cultivate in 2016, I was intrigued and excited by the idea of drawing on a place—an assemblage of human and more than human actors—as a caregiver for youth wellbeing in a time of crisis. It seemed to offer so much more than just “therapy,” but a whole-body experience of care and transformation for young people in need. When we came to you, we could see how the ideas our team was using at the time around “surviving well” through cultivating commons were being implemented and stretched further. But before we get there, could you tell us a bit more about Cultivate, the context of how it started, and what it does?

Bailey Peryman Cultivate is an urban farm and youth wellbeing project in Ōtautahi, Christchurch, Aotearoa New Zealand. It integrates youth employment training and skills development into the operations of an organic urban farming system. This system supplies organic produce to local residents and hospitality customers while taking their organic waste in return for composting. It’s a circular economy that supports working with youth in need of additional care beyond that which is accessible to them, either via family or government or otherwise in the community. The main vehicle for this is employment and opportunities to volunteer in groups. In doing so, it also taps into the capacity of a particular place to actually nurture people, a kind of reciprocal arrangement for the caring we do for soils and with the diversity of life already co-existing there.

In terms of how it got started, Fiona Stewart and I founded Cultivate together in 2015 after a nine-month intensive design and planning phase. The project was born out of an invitation to collaborate as alumni of the Vodafone New Zealand Foundation. It has grown up in the context of natural disasters, local emergencies, and global crises. In the past ten years, this region has witnessed major earthquakes, tsunamis, major fires, political removal of regional democracy, a terrorist attack, and a global pandemic—all of which have claimed many lives. Fiona and I chose “cultivate” as a working title for the project and both wanted for it to be an urban farm school for youth with learning and behavioral difficulties. Fiona has a background in youth development, mental health, and education and also grew up on a family sheep and beef farm in South Canterbury. I have formal training in environmental management and professional planning, plus experience with setting up local food initiatives. We both had strong support networks and healthy lifestyles that, when combined, made for a comprehensive foundation to start with. We had mentors around us to support each phase and this eventually developed into a governance group that shared legal and decision-making responsibilities, as well as a lot of the technical grunt work needed to form an organization.

KD What is your role within the organization?

BP I left the organization in 2020. However, during my time there, my part in the leadership of Cultivate was focused on the design, build, growth, and sustainability of the urban farming system. The first farm we established is built on compacted rubble in the inner city of Christchurch, where over 70% of buildings have been demolished due to earthquake damage since 2011.1 This particular parcel of vacant land is 3,000 square meters (0.75 acres) that we “commoned” via the voluntarily participation of both the land owner and ourselves.2 Our goal here was to work with young people in a community setting, to build the farm, to connect youth with their surroundings, to feel invigorated by the energy of a working farm and collective, and most of all, to share in the success and continue forming the project into something that worked well for as many people as possible.

KD How do you understand the meaning behind what you do at Cultivate?

BP Cultivate creates an environment and a system of welcoming people into the space where therapy can happen organically. It now engages more than 600 youth, guests, and community volunteers per year on top of ten-to-twelve paid “employment training” youth internships. Many have commented to me on how the farm is the only place they truly feel safe. Previous interns (sometimes with their grandparents) often return to say hello and make staff emotional with their own stories of personal growth.

KD Beyond cultivating produce and serving as a space for community, what else does Cultivate do?

BP With each load of food scraps collected from local cafes and restaurants using an electric bike, we compost wood-chips delivered for free by arborists, building the productive capacity of the farm. Cultivate’s connectedness has also grown, and we have become frequent collaborators with the community. With staff generally guiding key activities, participants work alongside each other, learning together about creating healthy soil-plant communities in pursuit of the vision of a network of urban farms, powered and propagated by youth.

The Cultivate Christchurch electric bike in action on a fresh produce delivery. Photo by Clinton Lloyd, 2018.

KD Cultivate is a great name for what you have done. I have often thought about what you are cultivating there. It is not just vegetables, obviously, but different sorts of subjects—perhaps commoners, and thus different kinds of possible futures. It seems like it is about creating a space which nurtures different possibilities for individuals, human communities, and communities that include other species. Could you tell us a bit more about your inspiration for the kaupapa of Cultivate and your current work in Ōtautahi Christchurch?3

BP Paying attention to the space and place in which care is practiced is not always recognized by everyone working with youth. I remember feeling shocked at my first trip to a local alternative education school we visited in our early efforts to start inviting youth into our space. The youth we targeted were kids who had been excluded from mainstream education, often with a foot in the justice system and almost always coping with background mental health issues, neglect, violence, and poverty in their home environment—if they had a home. Their learning environment was an old office space accessed through a carpark shared with liquor stores, fast food outlets, busy traffic intersections, and bars with multiple forms of gambling available, all conveniently located next to the government welfare agency’s local office. We felt that we needed to get them into a space where they could receive more positive signals from the world without necessarily removing them from their local community and family support networks. Coping is not living.

KD So are you saying that resilience is a practice, not a state of being?

BP Yes, resilience is definitively a practice. I hear our local senior public officials saying that Christchurch has so much to offer a global audience in terms of experience in disaster resilience. I agree, and yet our resilience didn’t just happen to us; we have to cultivate it continually and find places where our innate desire to thrive will come to life. This is where the practice of resilience becomes about finding ourselves as individuals, where we belong, and as collectives living within more than human worlds, altogether expressing our unique gifts.

KD A lot of people in Christchurch feel worn out by the idea of resilience, and got sick of people telling them they were resilient, especially as years of fights with insurance and difficulties with adequate housing in the winter started to take their toll. It seems to me that your work at Cultivate does not just ask people to be individually resilient, but offers a space in which care is built into the landscape and the practice, building resilience.

BP Yes, I’m particularly inspired at the moment with readings on care ethics, such as the feminist philosopher Joan Tronto’s recent article on homines curans (caring people).4 I can relate to the discussion on moving from caring about this place to actively caring for and with it as part of my journey that lead to the founding of Cultivate. I was striving then and do still put a fair amount of consideration into how to embody the ethics of people care, earth care, and fair shares that define the permaculture movement. These ethics are followed by principles, strategies and techniques that have played a significant part of how Cultivate has come to form with the respective places it works.5 For me there is a spiritual dimension to permaculture practice as well, which is fundamental. I am inspired by Māori culture that invites participants to include spiritual awareness of space in everyday life. It is an honor to receive acknowledgement of these practices working holistically from the wide range of people involved in supporting Cultivate’s development.

KD The kaupapa of manaakitanga is a powerful one indeed.6 The research we did interviewing Cultivate youth certainly supported the idea that the hospitality of the staff, the organization, and the place itself were important. It seemed that something about working together in place and with place spoke to youth in ways that “youth interventions” based on job readiness or social counselling might not. One interviewee in our project talked about the value of transplanting seedlings:

it’s quite therapeutic, I’d say…if I’ve had a lot going on…if I do that kind of job, it kind of gets me to focus on that more, just focusing on the little seeds and putting them in…So instead of getting all wound up about my personal life, [it’s just] me focusing outside and just gardening, and, like, helping the seeds grow.

I’m also thinking of another intern who spoke of how he would go and have a “lie down” at the end of the row in the grass, and look at the sky and just be for a bit. There was another who told us that it was the working together as community with the soil, the plants and the people that inspired him. I asked him what he appreciated about this and what he said was intriguing:

Just the actual feeling, the energy from what earth actually has to offer I think. Just actually, oh, it’s just a bit of soil. But soil can make a whole oak tree. It can be a whole other thing with just a seed and a bit of care and love and all that… So you put, I think, all that brainstorming stuff together and you’ve got this one awesome void [sic] of cool people with cool plants and all that sort of stuff.

I can see how the place and landscape itself really speaks to the people that come there, and cares for them in a way. Could you say a bit more about how that interaction between youth and place has been intentionally built into your philosophy and practice, both at Cultivate and since?

BP I grew up in a sheltered beach village, with a temperate coastal valley climate and numerous opportunities for recreation, from organized sports to nature play in the hills or the ocean. The sounds, the atmosphere, and community feelings were akin to a haven. I think it trained me to appreciate just how unlike a sanctuary many parts of our world are. Learning about the political and economic forces creating these destructive and dysfunctional urban forms and being grateful for my privileges has been a source of motivation to be more effective at co-creating more positive environments with youth and for future generations. The other critical dimension of working with place is that each has its own unique energy, as if every farm has its own signature. Working intentionally with a place can evoke powerful feelings in those present. I witnessed young people in Cultivate farms having lightbulb moments while learning and seeing in front of them, the connections between our bodies, the living world around us and the choices we are making every day. What we eat, where it comes from, how it became food and why this matters are all fairly profound realizations to experience irrespective of your background and education. This is the starting point for beginning to better articulate the places we want to inhabit.

KD It really struck me that the safety of Cultivate was like the safe attachment that a baby might have to a parent, where they initially need to be calmed by the parent, but how the continual calming and feeling of “alrightness” that the parent gives can then be internalized. It’s like the youth don’t attach to one single “parent” here, but a place and community of safety that then allows them to also be an individual. Does this capture some of what you are trying to achieve with the concept of havening? How is that playing out in your current work?

BP One of the key decision-making criteria for where Cultivate operates has always been about accessibility for young people and the community. The place has to read like an environment that youth will cross a threshold for and enter into. I think sometimes designing for this can be akin to theater, as if a play of life, working with the place to create a future haven. I am keen to play a role in mobilizing existing and new communities of practice towards co-creating future havens.

KD Tell us a bit more about where you are going next with this work.

BP After giving and receiving so much in the process of co-creating Cultivate, leaving to enter new fields has been a leap of faith.7 I am here on this planet to support a proliferation of urban agriculture and the rekindling of soil-plant communities with people in their local environment. Food systems influence every human life on this planet. A healthy soil is a series of diverse relationships that together support thriving ecosystems, our sources of sustenance and community. Given the climate, health and biodiversity emergencies and associated pressures on human populations we’re experiencing collectively as a planetary species, it stands to reason that we ought to be channeling much greater energies into reconditioning our soils for vitality. I see part of my project now is to mobilize a decentering of the food systems of Christchurch using holistic havening practices.

KD Where will you begin?

BP I’m (re)starting with collectives that are diverting centralized organic “waste management” flows into community hubs, which I think will in turn restore integrity to local nutrient cycles that support agro-ecological and indigenous ecosystem health. I was reading the other day that food security has suddenly become “a national and pressing matter of concern” for many people in Aotearoa New Zealand.8 I’m interested in the possibility of performing a transformation of community food security on a civic scale, starting in the areas of greatest inequity and need. My research is also concerned with the ongoing loss of precious topsoils, largely to poor agricultural practices, and the relentless march of greenfield housing developments on remaining versatile soils.9 Christchurch’s “residential red zone” alone still has 600 hectares (1,500 acres) of river corridor, wetland, and lowland coastal ecologies to recover from impacts of the 2010–2011 Canterbury earthquakes.10 I believe a transition can happen a lot faster than many (including myself) can possibly imagine right now. In any case, we may be forced into this change in the inevitable event of future shocks to our ecosystems and communities.

KD I know you are thinking about the word “havening” as something that describes the kind of ethic of care practiced at Cultivate. Is this something that we could explore further in this sort of work?

BP I am aware that havening is a healing modality that already exists and this is practiced by Cultivate’s co-founder, Fiona Stewart.11 The collectives I am part of are intentionally spending more time with the practices we’ve already mentioned, such as intentionally working with place as caring and supporting of wellbeing. Our exploration is about continuing to develop havening as a design method and a practice, stuff which can be done in real time, for example, through linking commercial property development opportunities with place-based communities. These moments are inviting us to be creative, reflexive with our thinking, and feel our way into embodying havening as a practice. What is being achieved with Cultivate and in these various other settings is really important to ruminate on. There are many more instances where people want this to happen too. I want to be in positions where I can support, expand myself in the process, keep learning, and open new possibilities for other people to enjoy life as much as possible.

See Charlie Gates, “1240 Central Christchurch Buildings Demolished,” stuff, February 20, 2015, ➝.

This connection was brokered through the Life in Vacant Spaces Trust (LiVS), an organization created post-earthquake, which has enabled Bailey Peryman to test a diversity of different local food initiatives. The land is accessed legally via a rolling lease with a thirty-day notice period and a verbal tenure agreement of two to five years.

In Te Reo Māori, the word kaupapa encompasses a number of meanings. Here, it is used to refer to a set of agreed principles or values that a group is working with; see: Te Ahukaramū Charles Royal, “Papatūānuku—the land—Whakapapa and kaupapa,” Te Ara—the Encyclopedia of New Zealand, September 24, 2007, ➝. It is used fairly regularly in New Zealand English by people of any cultural and linguistic background.

Joan Tronto, “There is an alternative: homines curans and the limits of neoliberalism,” International Journal of Care and Caring 1, no. 1 (2017): 27–43.

See “Permaculture Principles,” Permaculture in New Zealand, ➝.

Manaakitanga is a Te Reo Māori noun encompassing hospitality, an ethic of care and generosity. It is sometimes used in New Zealand English; see: Molly Mullen and Bōni Te Rongopai Tukiwaho, “Taurima Vibes: Economies of manaakitanga and care in Aotearoa New Zealand,” in The Routledge Companion to Applied Performance, vol. 1, eds. Tim Prentki and Ananda Breed (Oxon and New York: Routledge, 2021), 43–55, ➝.

You can learn more about the state of Cultivate as of January 2020 by listening to the following podcast, captured at the time author Bailey Peryman was committing to moving out of the organisation: “Food: The Healer,” The Why We Grow Show, January 8, 2020, ➝.

Kelly Dombroski et al., “Food for People in Place: Reimagining Resilient Food Systems for Economic Recovery,” Sustainability 12, no. 22 (2020): 9369, ➝.

This is a vast corridor of land that, since the 2010–2011 earthquakes, is no longer considered stable enough to build upon. See: “Christchurch residential red zone areas,” Land Information New Zealand, October 14, 2020, ➝.

For more on certified havening practices, see Frances Lamb, “What is Havening,” Havening, 2020, ➝.

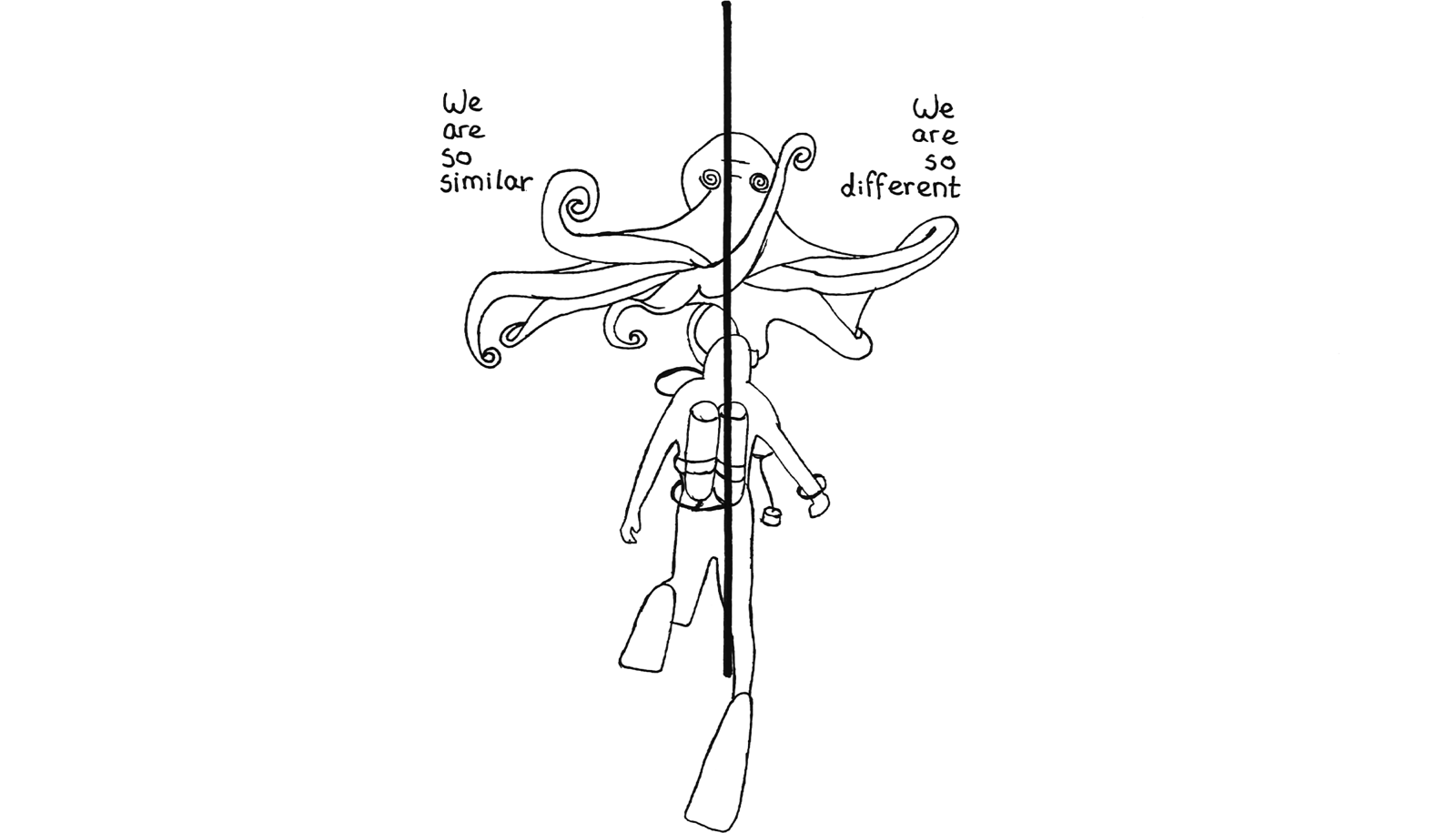

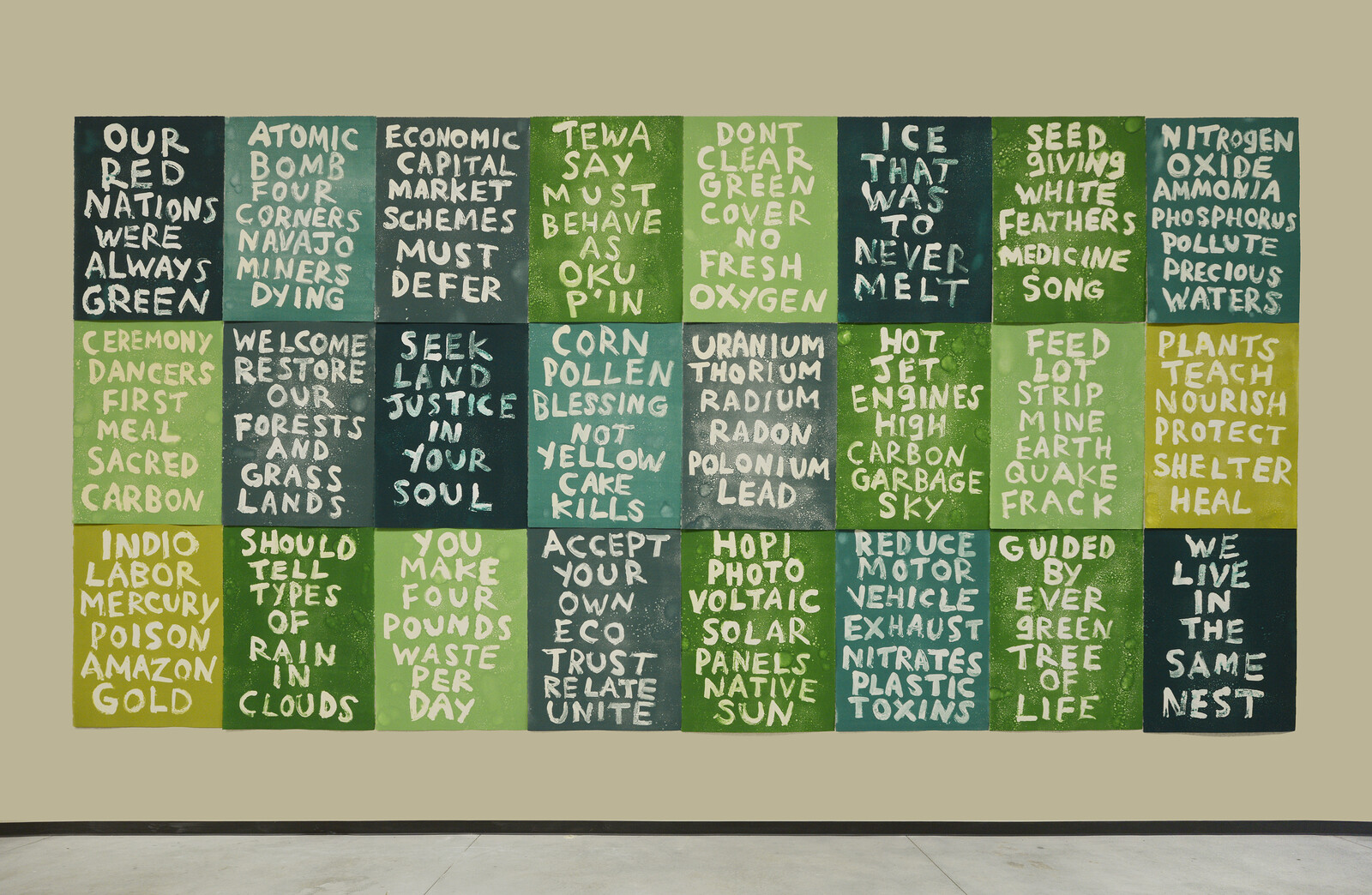

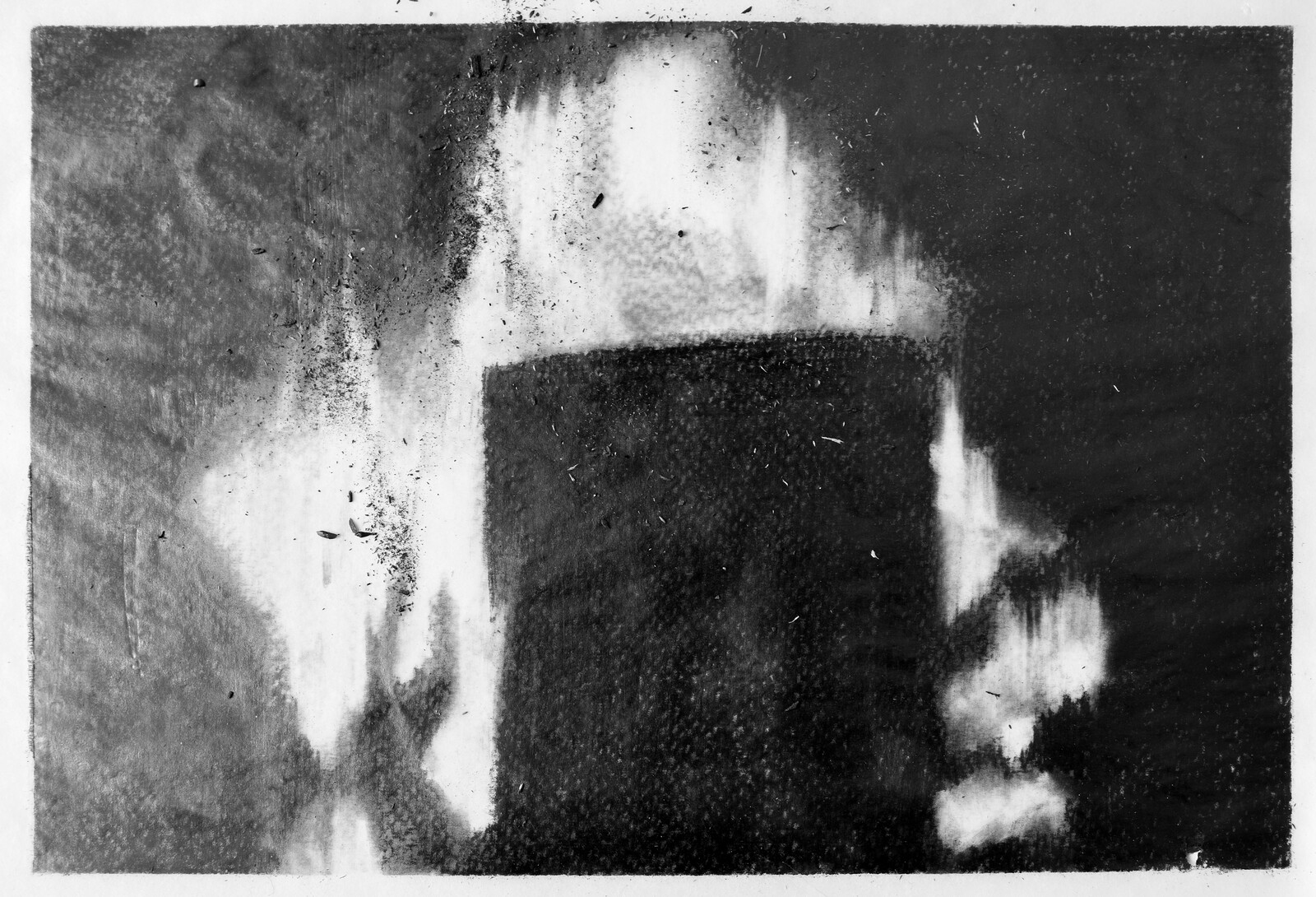

Survivance is a collaboration between the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum and e-flux Architecture.

Category

Subject

The authors would both like to acknowledge Fi Stewart and the staff and interns at Cultivate, without whom this piece would not be possible. Thanks to Clinton Lloyd, Sophie Merkens, and Cultivate Christchurch for the images. Kelly would like to acknowledge funding from the National Science Challenge Building Better Homes Towns and Cities, for the project Delivering Urban Wellbeing for Transformative Community Enterprise. She would like to acknowledge her collaborators Gradon Diprose, David Conradson, Stephen Healy, and Alison Watkins, particularly Gradon and David, who conducted some of the interviews quoted. Bailey would also like to acknowledge scholarship funding from Building Better Homes Towns and Cities, part of the Huritanga Systems Change for Urban Wellbeing program.

Survivance is a collaboration between the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum and e-flux Architecture.