In the small north island township of Tāneatua stands Aotearoa New Zealand’s first living building. This building, known as Te Kura Whare, is located near the fringes of Te Urewera, a mountainous and forested terrain that covers over two hundred hectares and is ancestral homeland to Ngāi Tūhoe, or “children of the mist.”1 Te Urewera is not only bustling with life of various forms: she is life—of Papatūānuku, Earth mother.2 It is due to the leadership and unwavering advocacy of Tūhoe that New Zealand law now recognizes Te Urewera as a living entity, with legal rights of personhood.3

The Living Buildings framework, as set out by the International Living Future Institute, awards the title of “living building” to regenerative dwellings that not only limit negative impacts upon the biosphere but mitigate these impacts altogether.4 There are a growing number of such buildings around the world, and each has its own story to tell. Te Kura Whare serves as the first tribal headquarters for the Ngāi Tūhoe tribe, and, more broadly, as a community center and cultural hub for both Tūhoe and manuhiri (visitors) alike.

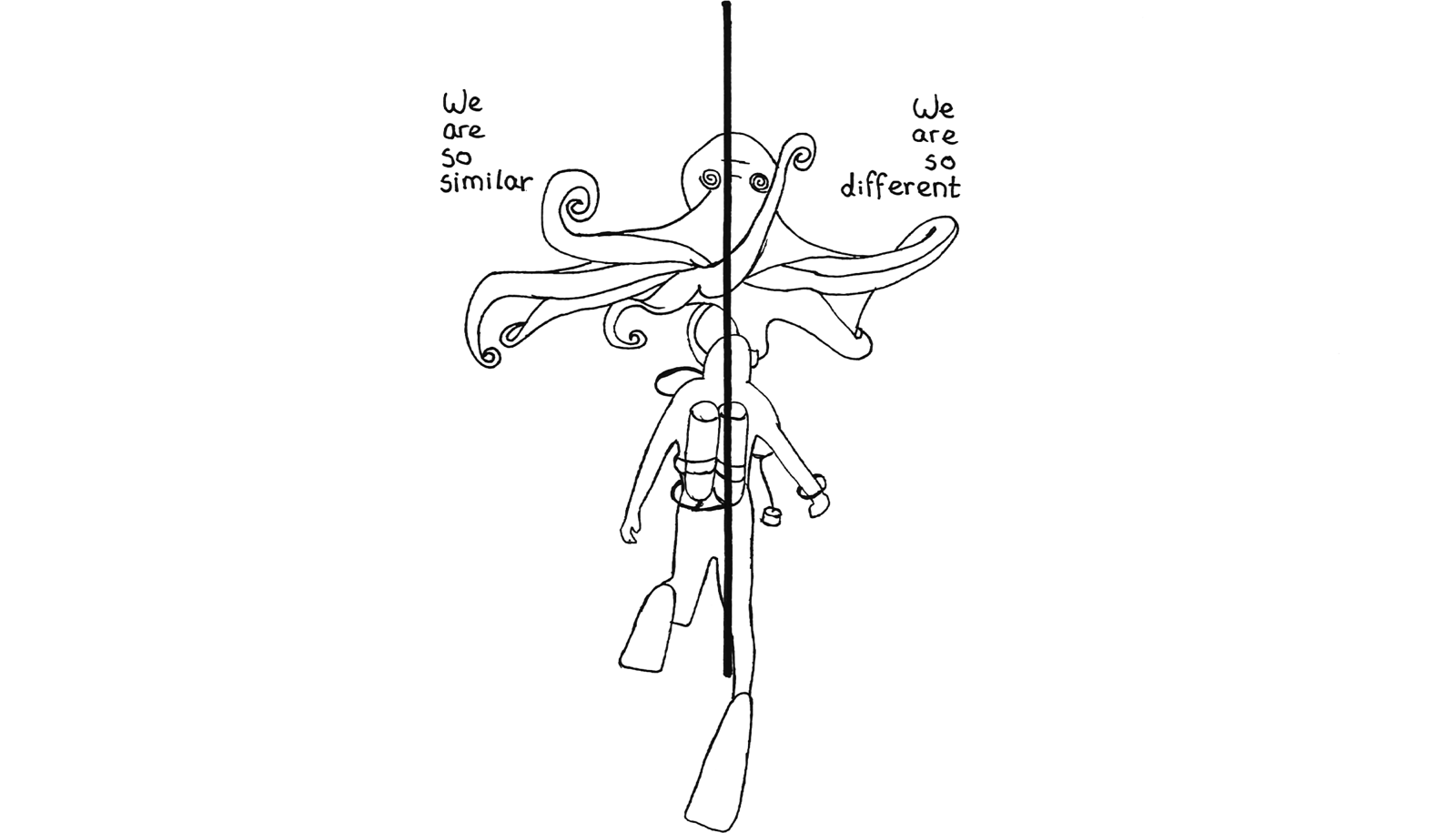

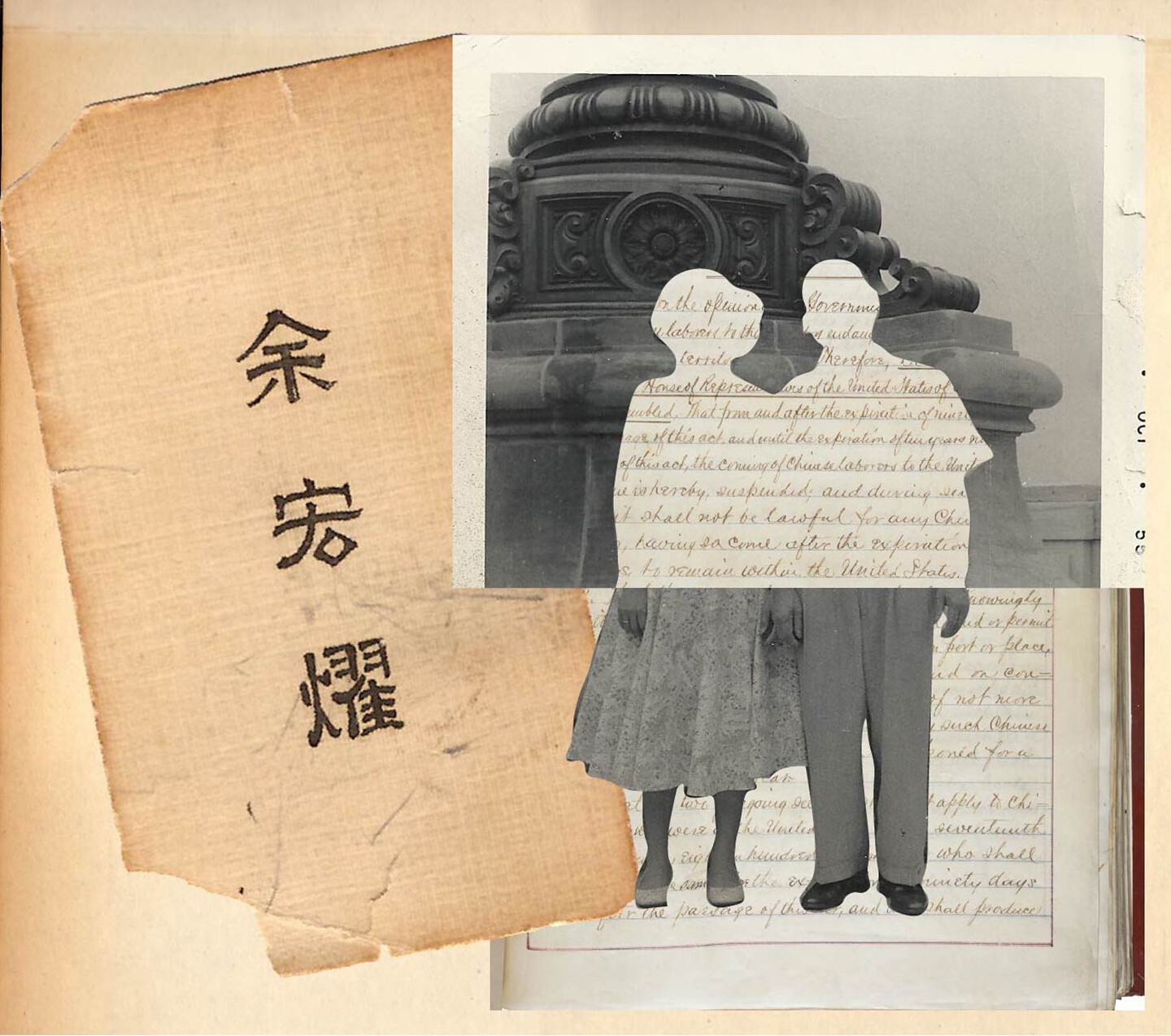

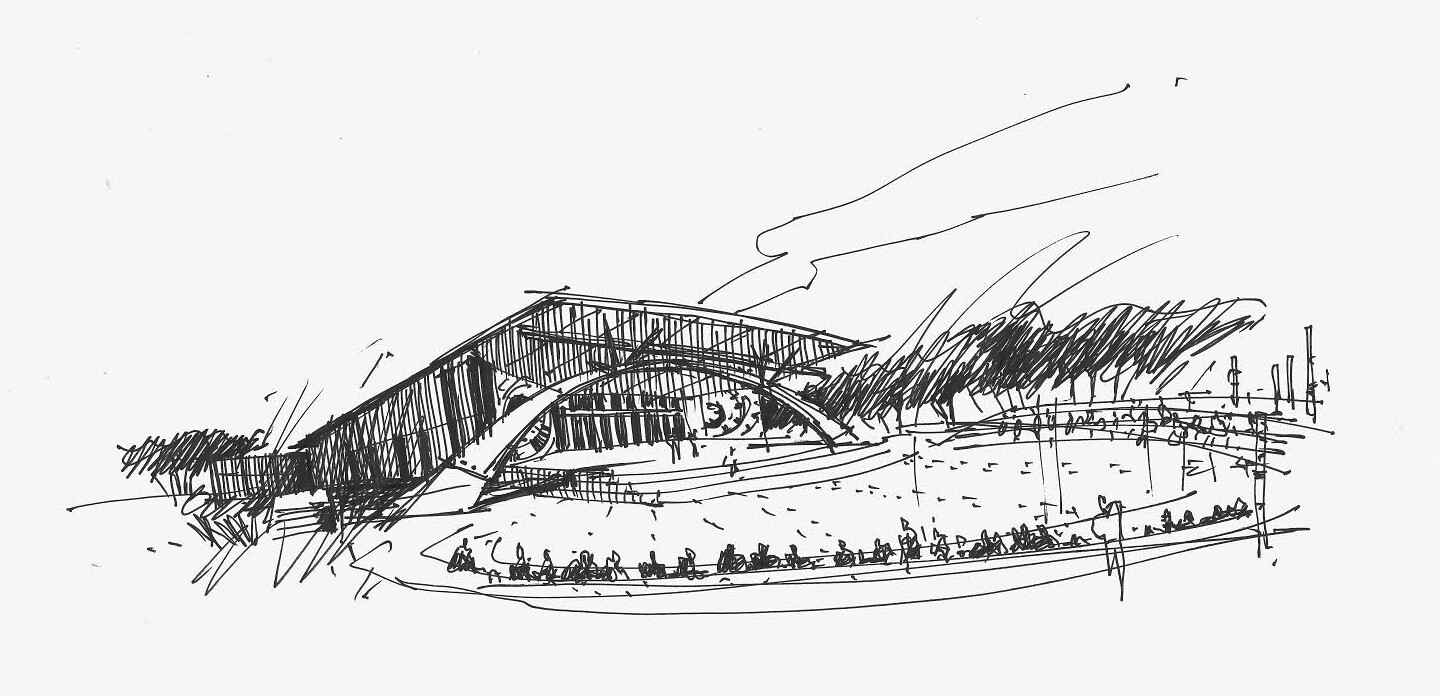

Sketch by Hamish Boyd, principal, Jasmax.

As noted by the International Living Future Institute, the intention for Te Kura Whare was clear from the very beginning: to be “an architectural representation of the Tūhoe people—their beliefs, traditions, culture, and history.”5 In order to realize this vision, Tūhoe, in collaboration with the (late) New Zealand architect Ivan Mercep and his team at Jasmax, followed the Living Building framework.6 Their aim—and mission—was to ensure the construction of a building that avoided creating any negative bearings upon the environment (achieved through net-zero energy, water, and waste), as well as having an ongoing regenerative impact on both the environment and the local community.7 Te Kura Whare is as much about capacity building, community building, and hope as it is about kaitiakiatanga, or guardianship of the environment.8 One of the guiding principles in the construction of Te Kura Whare, and the aspirations Tūhoe had for the building, was that of matemateone: a principle that can be translated as a form of “kinship love” and “love for all creation.”9

Since its construction in 2014, Te Kura Whare has received international attention and has been frequently noted as exemplary in terms of its biophilic design and wider cultural significance.10 Indeed, this building illustrates what is possible in terms of approaching design and architecture—and for that matter, community building and cultural regeneration—with bold aspirations and the meshing of indigenous worldviews grounded in nature alongside technologies capable of producing the most self-sustaining and regenerative buildings possible.

With strong biophilic design elements and a commitment to cultural preservation and regeneration, Te Kura Whare connects to and reflects Te Urewera throughout. Te Kura Whare is comprised of offices and meeting rooms, a Tribal Chamber, an amphitheater, a café that specializes in local cuisine (including food grown in gardens on site and infused with flavors both endemic to Aotearoa and inspired by Te Urewera, such as kawakawa and horopito leaves), as well as a cultural repository in the form of a library and archive dedicated to the preservation and presentation of Tūhoe history. Its structure is formed by locally supplied (and sustainably sourced) timber, including matai, rimu, tawa, and totara that had fallen within Te Urewera.11 These contributions are particularly important, as the wood used in the building has its own whakapapa, or emplaced genealogy and symbolic meaning. Its earth bricks, which provide the thermal mass that regulates air temperature and humidity inside the building, consist of clay sourced from local areas and constructed by-hand by members of Tūhoe nation, young and old. Additionally, logs throughout the building act as posts, trusses, and beams in a way that mirrors the structure of a living forest. Likewise, distribution of natural light throughout the building is intended to create a sensorial experience that emulates sun rays and shadows, reminiscent of a forest setting.12

Prior to European colonization, Tūhoe routinely lived in a way that reflected their deep and reciprocal relationship with Papatūānuku and her non-human children (their kin). This meant that many of the community’s basic needs were sustained by the land and through their connections with kin, human and non-human alike.13 Aspects of this relationship were severely undermined through colonization, which began in Aotearoa in the nineteenth century. As Tūhoe have expressed: “Our disconnection from Te Urewera has changed our humanness [and] we wish for its return.”14 Colonial powers subjected Tūhoe to what has been termed a calculated genocide.15 Wrongful killings, police raids, and various miscarriages of justice occurred alongside pillage and the confiscation and destruction of fertile lands, crops, and cultural taonga, or treasures, which included traditional knowledge, practices, and lifeways.16

Te Kura Whare symbolizes and conveys the journey and evolution of Tūhoe and their ongoing commitment towards healing their people and the land. Te Kura Whare can be seen as the mauri, or the living, expressed life-force of Tūhoe, and representing a rebirth, regeneration, and restoration of mauri within a profoundly-felt post-colonial context.

Tūhoe Te Uru Taumatua.

Tūhoe Te Uru Taumatua.

Tūhoe stories are conveyed through artwork and design featured throughout Te Kura Whare. The construction of an arch at the entrance of the building’s Tribal Chamber, for example, “simulates the flight path of Tama-nui-te-rā [the sun] across the sky, from east to west” and “represents potential … [reminding] Tūhoe to look forward, rather than backward at the bitter legacy of colonialism.”17 Various motifs, symbols, and color choices feature as crucial (and intentional) design elements throughout Te Kura Whare, reinforcing connection to people and place while simultaneously providing an architectural expression of core principles tied to Tūhoetanga, or Tūhoe identity.

The construction of Te Kura Whare occurred at a significant point in time for Tūhoe, coinciding with long-overdue reparations by New Zealand’s Crown.18 Part of these reparations involved a monetary settlement (part of which paid for the building), but far more important to Tūhoe was the return of Te Urewera herself, which had from 1954 until 2014 been established as a national park and subjected to decades of commercial logging. The return of Te Urewera created an opportunity for Tūhoe (and wider Aotearoa) to re-connect with Te Urewera. The key guiding document for these processes, Te Kawa o Te Urewera, has its emphasis not on managing Te Urewera, but rather on instructing humans tasked with her care and protection. This is reinforced through the Treaty document’s intentional use of language such as “friendship agreements” in place of “concessions.”19

Prior to the construction of Te Kura Whare, Tūhoe engaged in a series of early blueprint discussions whereby Tūhoe leadership sought input from Tūhoe throughout the country (and the world) in order to ask what a Tūhoe future might look like.20 Key themes to emerge during these conversations linked to (re)connection with place and the advancement of mana motuhake, or self-determination. As part of this process, the vision for Te Kura Whare was born. Features such as the building’s 352 solar panels support these aspirations, enabling life to occur off-grid.21

Kirsti Luke, Chief Executive Officer at Tūhoe Te Uru Taumatua, has shared the Tūhoe saying: “people build a building, but a building raises a people.”22 Hundreds of Tūhoe members (of diverse ages and backgrounds) pitched in to support the building’s construction. Their contributions took multiple forms, ranging from the felling of trees to the clearing of fences on site, locating native trees, milling wood, making earth bricks by hand, hammering floors, building walls, painting ceilings, preparing food for the workers, installing systems, planting trees and gardens, concreting driveways, and more.23 The building process—as well as the finished result—created multiple learning and training opportunities for those involved. A number of Tūhoe members, for example, secured full time employment as part of the process.24 As the New Zealand Property Council also noted, when announcing Te Kura Whare as the winner of their 2014 Green Building Award: “the level of community involvement achieved by the project has been transformational, with the skills developed now being used on a number of new projects.”25

Part of the Living Building Challenge criteria necessitates that the origin of each building material is known and that they do not contain any prohibited “Red List” materials.26 As such, every piece of material used in Te Kura Whare was researched and added to a comprehensive tracking sheet in order to ensure compliance and best practice, showing just how mindful and deliberate the process was, from start to finish.27 Te Kura Whare has now established a benchmark for buildings throughout the Tūhoe region.28 Its legacies also extend wider than this, particularly in terms of strengthened ecological awareness within New Zealand’s building industry.29 As Jeff Vivian, former Project Director at Arrow International, the third largest construction company in New Zealand, noted in an interview, his involvement in the construction of Te Kura Whare had a significant impact upon his experiences, practices, and views around building.30 As part of the process, Vivian and others involved were guided by the Living Building Challenge’s function as an advocacy tool. This required that they not only ensure they were sourcing compliant materials, but that they also write to companies identified as not meeting these requirements, to educate them about the toxic or otherwise unsustainable elements of their products and request that they consider supplying more ethical alternatives. With this, Vivian and his team became increasingly cognizant of the often “nominal cost difference between good and bad [materials]” and left the project with the view that “good materials” should—and, realistically, could—become more standard within New Zealand’s wider building industry.31

There is much to be learnt from Te Kura Whare, and in particular, from the care that Tūhoe have extended to the building, and to the living entity (Te Urewera) that it pays homage to. The full extent of the building’s transformative impacts is yet to be seen and will continue to unfold over the generations to come. In the meantime, however, other challenges inevitably persist. Tūhoe are navigating the complex processes of healing and (re)connection while facilitating their post-Treaty settlement transition. The extent of this challenge has been articulated by Tūhoe leader Tāmati Kruger, expressed the need to acknowledge the multiple impacts of colonization and the imposition of worldviews and ideologies that were antithetical to Tūhoe ways of being, and how such disconnective practices, common throughout industrialized, “westernized” contexts, have steered Tūhoe away from living in ways that reflect their ideals and duties as Tūhoe people.32 To remedy this, Kruger has noted:

We have given ourselves around about forty years, or two generations, to do something about that… [We know] that we are attached to nature, we are attached to Te Urewera, but there has been great damage to that whakapapa, to that link, over 177 years.33

These changes won’t happen overnight, as signaled by the long-term visions held by Tūhoe. Time, however, is no deterrent to Tūhoe, who know a brighter future is not only possible, but already unfolding. As Kruger emphasizes, a central part of the process involves the deliberate “unlearning” and “re-learning” of what it means to be human and to live in a way that reflects Tūhoe values and worldviews, grounded in nature. Te Kura Whare, and all that it stands for, is an integral part of that process.

The meaning behind their name, and the deep connection that Tūhoe have with Te Urewera, can be traced back to ancient times, and more specifically, to a union between Hinepūkohurangi, the Mist Maiden (who came from Rangiroa, the lofty heavens and Rangimamao, the distant sky) and Te Maunga, the mountain. The union between this pair resulted in the creation of a son, Pōtiki, and, in the generations to follow, in the birth of the Tūhoe people. See: John H. Alexander, “Maungapohatu: An Epoch in History,” Te Ao Hou, December 1959, ➝.

Tūhoe, “Te Kawa o Te Urewera—English,” Ngāi Tūhoe, 2017, ➝.

“Ngāi Tūhoe,” New Zealand Government, 2021, ➝.

The International Living Future Institute is a non-profit organisation based in Seattle (but working globally) that seeks to promote, and work towards, the vision of a world that is ecologically healthy, socially just, and restorative. It has several initiatives designed to enact a “living future,” focused upon buildings, products, and communities.

“Healing From Within: Te Kura Whare,” International Living Future Institute, 2021, ➝.

The Living Building Challenge, created by Jason McLennan in 2006, is guided by the view that design and construction can make the world a better place. See “Living Building Challenge,” International Living Future Institute, 2021, ➝. This challenge—or invitation, as it might also be viewed—is not bound to one category, but instead operates simultaneously as a philosophy, a certification programme, a toolkit, and a means of advocacy for the advancement of regenerative architectural and building practices. Its influence is spreading throughout the world in what its founder, McLennan, describes as an architectural revolution. See TEDx Talks, “Living Buildings for a Living Future | Jason McLennan | TEDxBend,” YouTube, May 26, 2015, ➝.

Ever the Land: A People, a Place, Their Building, dir. Sarah Grohnert (2015; New Zealand: Monsoon Pictures International).

Kaitiakitanga is a principle that stands in stark contrast to westernized notions of land “management.” The late Māori elder and tohunga Hohepa Kereopa elucidated what it means to be a kaitiaki as thus: “When one considers kaitiaki, you have to consider for what purpose it is being used. If you have a pipi bed {pipi is a local crustacean}, for example, you cannot talk about kaitiaki until you know about all of concepts and life of the pipi. So you need to know how to keep the pipi safe, but you keep it safe for the pipi’s benefit and not for your’s {sic}. Because the job of kaitiaki is to keep the things of Creation safe. The return from this is the relationship you get with the thing you are protecting, and the knowledge and learning that comes from that…So if people want to exercise kaitiaki, they will first need to understand the value of all things…For us, this does not mean being in charge of things…It’s about knowing the place of things in this world, including your place in this world.” Paul Moon, Tohunga: Hohepa Kereopa (Mangawhai: David Ling, 2003), 131.

Ibid., 171.

“Healing From Within,” International Living Future Institute.

Ever the Land, dir. Grohnert.

“Healing From Within,” International Living Future Institute.

Moon, Tohunga.

Tūhoe, “Te Kawa o Te Urewera,” 8.

Judith Binney, Encircled Lands: Te Urewera, 1820–1921 (Wellington: Bridget Williams Books, 2016).

See: Binney, Encircled Lands; Paul Moon, When Darkness Stays: Hōhepa Kereopa and a Tūhoe Oral History (Mangawhai: David Ling, 2020); Kennedy P. Warne, Tūhoe: A Portrait of a Nation (Auckland: Penguin, 2013). Significantly, armed police raids in Te Urewera occurred as recently as 2007, and as such these types of actions are not just part of a disturbing distant past. See The Price of Peace, dir. Kim Webby (2015; New Zealand: NZ On Air and Māori Television).

“Healing From Within,” International Living Future Institute. Also note that in the legend of Māui, particularly in his guise as Māui-tikitiki-a-Taranga, work during the day was made possible by the simultaneous slowing down and diminution of the powers of the sun with the ensnaring. Any depiction of Tama-nui-te-rā has the idea that work is to be valued implicit in its depiction (author’s communication with Lloyd Carpenter).

These reparations were formalised through the Ngāi Tūhoe Deed of Settlement, initialled by Tūhoe and the Crown on March 22, 2013, and subsequently ratified and signed by the people of Tūhoe on June 4, 2013. See “Ngāi Tūhoe,” New Zealand Government. This settlement process occurred at the end of a prolonged and emotionally difficult claim consideration process which subsequently morphed into a lengthy claim settlement process. The Waitangi Tribunal (a permanent standing Commission of Inquiry within Aotearoa that works with claims made by Māori to determine where and how Crown actions may have breached the principles of New Zealand’s founding document, the Treaty of Waitangi) was the mediator that saw the settlement recommendations and monetary compensation provided to Tūhoe through the (then) Te Kāhui Whakatau/Office of Treaty Settlements (now the Office for Māori Crown Relations—Te Arawhiti).

Tūhoe, “Te Kawa o Te Urewera.”

Justine Murray, “A people build a house, and a house builds a people,” Radio New Zealand, May 21, 2017, ➝.

“Healing From Within,” International Living Future Institute; Murray, “A people build a house.”

Property Council, “2014 PCNZ Best in Category Green Building Property Award,” YouTube, June 11, 2014, ➝.

Tūhoe, “Te Kura Whare: The Approach,” Ngāi Tūhoe, 2015, ➝.

Lesley Springall, “Surviving New Zealand’s First Living Building,” ArchitectureNow, March 5, 2014, ➝.

Property Council, “2014 PCNZ Best in Category Green Building Property Award.”

The Red List is comprised of materials, chemicals, and elements which, despite often being prevalent and easy to source within mainstream construction, have been recognized as posing potentially significant risks to environmental and human health. See “About the LBC Red List,” International Living Future Institute, 2021, ➝.

Ever the Land, dir. Grohnert.

Tūhoe, “Te Kura Whare.”

Murray, “A people build a house.”

Springall, “Surviving New Zealand’s First Living Building.”

Ibid.

Tāmati Kruger, “We are not who we should be as Tūhoe people,” E-Tangata, November 18, 2017, ➝.

Ibid.

Survivance is a collaboration between the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum and e-flux Architecture.

The author offers her thanks and gratitude to Ngāi Tūhoe for their support and assistance with this article, as well as the inspiration for it. She also thanks Nick Axel, Troy Therrien, and Amba Sepie for their invaluable feedback and editorial assistance, as well as her research supervisors at Lincoln University—Lloyd Carpenter, Kevin Moore, and Christopher Rosin—for their support in writing this article, and for Lloyd’s valuable insights into te ao Māori, the Māori world.

Survivance is a collaboration between the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum and e-flux Architecture.