Having spent most of my life between cultural dissonance and cultural isolation, double consciousness has always been a part of my daily reality. Struggling to make sense of my otherness, I gradually began to romanticize Ethiopia, the country my mother had to leave behind during the “Red Terror” (Qey Shibir) in the late 1970s. This romanticizing took place in the absence of a positive narrative about Ethiopia, or about the African continent as a whole, in either the classroom, with my peers, on TV, in art museums, or anywhere outside of the places I called home. The dominant narrative I absorbed from the environments around me, and especially from school, was one that defined Africa as nothing more than a single tiny village of non-autonomous victims. There was no indication of its vastness, history, complexity, beauty, wealth, cultures, languages, of any contributions to global knowledge-generation, or of its possible futures. It was a far-away and undesirable place where only tragic things happened and where people always needed “our” help. From these environments, I was taught that we were less than human, and that this was our reality.

However, at home, I absorbed a completely different reality. It was my mother’s nostalgia that shaped my conception of Ethiopia. She told me fond stories of her childhood in Goree, of the fun she and her friends had during her time in nursing school in Gondar, of her adventures while working in remote parts of the country like Gambela, and then of her cosmopolitan city life working for Ethiopian Airlines in the capital. She lived through the trauma of Qey Shibir. She uprooted her life and migrated to the US by herself. Yet she was human. She had hopes and dreams, highs and lows. Her memories of a “regular” life in Ethiopia were precious to me. They stared boldly in the face of the dominant narrative of victimhood that society seemed so desperate to believe. Her nostalgia equipped me with an oral counter-archive, a counterimagining; an immaterial toolbox with which I could liberate myself from the double consciousness and dehumanizing hegemonic narratives I unwillingly internalized at school.1

My mother’s stories defined a surreal and fragmented dream of Ethiopia, my own heterotopia of sorts. Somewhere in between the reality of her memories and my need to construct an emancipatory and nuanced understanding of my culturally and racially mixed, half-first-generation identity, an imaginary nostalgia was born. This “inner landscape” was not sourced from my own nostalgia, but from the ideas I projected onto my mother’s.2 I depended upon a version of Ethiopia of my own design, both real and unreal; a virtual countersite, a productive space of illusion that I could superimpose over the hegemonic narrative, the simulation of the continent and my identity that I felt the burden to combat and correct every day.

This imaginary nostalgia was a space in which I was free from feeling like a contradiction of Black and white, East and West; free from the oscillation between invisibility and hyper-visibility. It was a decolonial space in which my mixed identity could exist unapologetically and without question; a place where home was post-spatial and encompassed impossible geographies. Although partially imagined and a bit magical, my imaginary nostalgia was the only “real” space that reflected my reality. Tezeta is an Amharic word that can be translated to “nostalgia” or “a state of longing.” Tezeta is also the name of a melancholic sub-genre of Ethio jazz which became the soundtrack of my childhood.3 I first unknowingly accessed my imaginary nostalgia through this music, but over time it became an intentional ritual.

In high school, I used to work at the Empress Taytu Ethiopian restaurant in Cleveland, Ohio. Although I didn’t fully understand the meaning or significance of working there at the time, I needed a space where I could enthusiastically and openly embrace my culture, where I could express pride in being Habesha. I saw myself there as an ambassador, and the customers my guests. On slow nights, I wished for every customer to order the coffee ceremony at the end of their meal so I could brag about how we are the birthplace not only of humanity, but also coffee. I’d tell them the legend of Kaldi and the dancing goat with exuberance.4 Frankincense burned on hot coals, tezeta music played, and I relished with pride when I nailed the delivery of the story, when guests were enthralled and left wanting more. With each recitation, it was as though I was making a case for the authenticity of my Ethiopianness, and simultaneously making a case for people to believe that there was more to being Ethiopian or African than what they might already think.

Looking back, it is frustrating that one of my few outlets of cultural pride at the time existed in the service of making a case for predominantly white people to see Ethiopia through a nonracist and nonreductive lens. I made their burden my own and then tried to correct it too. Despite this entangled dimension, I transformed this toxic hierarchical binary into an infrastructure for conversations that I wanted to have about Ethiopian history, traditions, cuisine, and contributions to the world. Although these stories were structured in a way that appears to replicate historical power structures, we don’t always have the ideal or most convenient life circumstances for liberating ourselves from simulations of our identity. Inconveniences and toxic binaries are ubiquitous; the question is how and when are we able to thrive despite and within them?

Emancipatory Storytelling

The image of Africa as inferior infected almost every instance, conversation, media or scholarly representation of the continent that I experienced while growing up in diaspora. This image was contrary to my sense of pride, and my own knowledge of the reality I had experienced –Africa as having so much value, both intellectually and culturally. This message of hierarchy and inferiority insidiously dominated my ability to perceive the continent as possessing any knowledge that could be of global relevance or prestige. As a child and young teenager, it never occurred to me that Africa could be a site of knowledge-generation. The image of the victim is essential to the perpetuation of the oppressor’s own self-perception as superior.

Identifying strength, recognizing erasure and internalization, understanding how it functions and is perpetuated, and actively seeking a counterimagining is an act of resistance. Drawing from the very cultures that are perceived as permanent and essential “victims” and portraying their value is not only contrary to the oppressor’s cycle of victim-creation, but it also subverts their messaging and can liberate those bound by it.

The essence of emancipatory storytelling is the continued presence of active traditions, spirit, cast of mind, and even humor. Wisdom and spirit need a space to live—whether that space be physical or immaterial, oral or digital, 1:1 or 1:∞. Active presence resists erasure and oblivion by living within a story told by a mother to a daughter, or told by a waitress to a customer; within the context of a restaurant, or an artifact of memory.

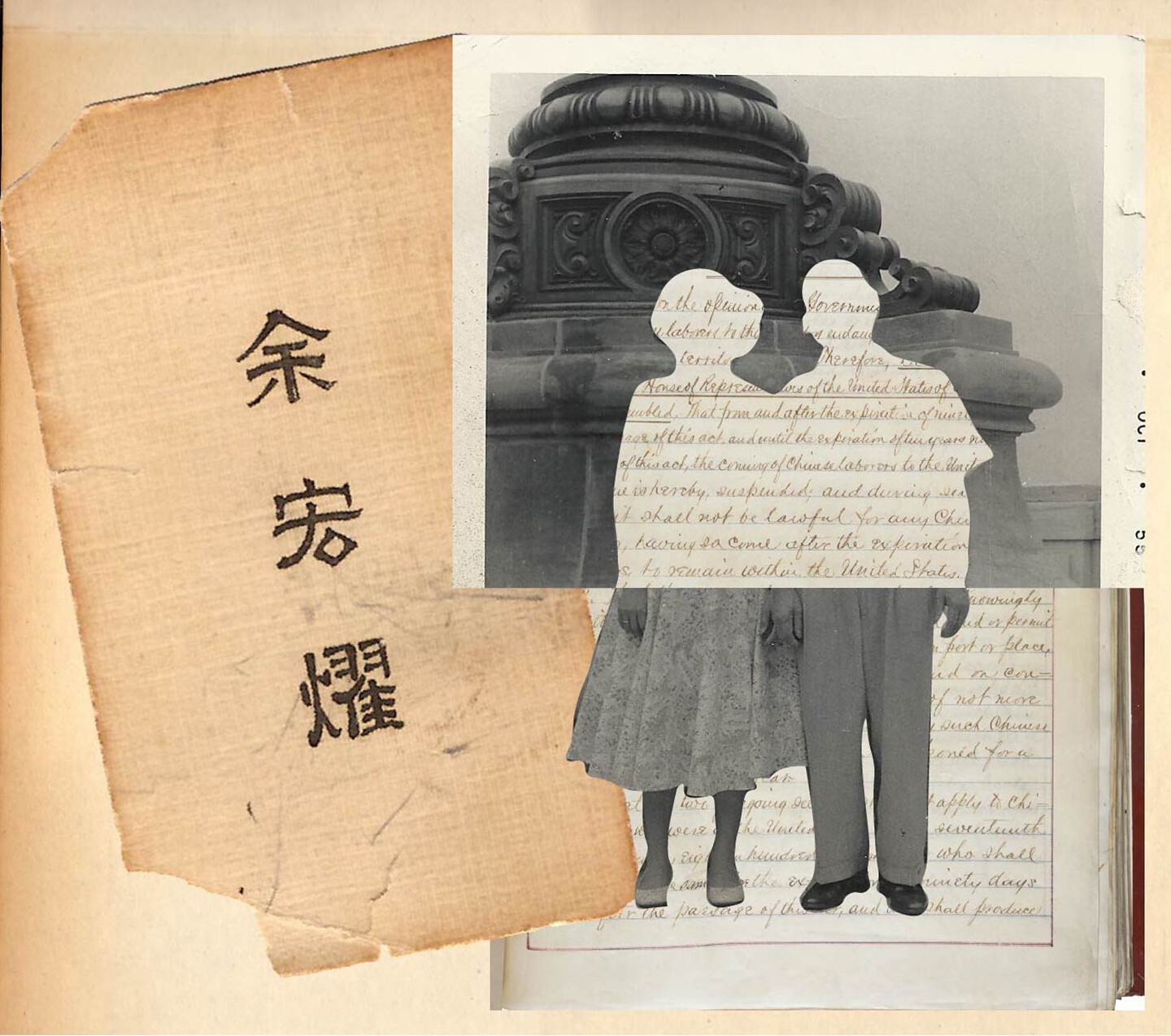

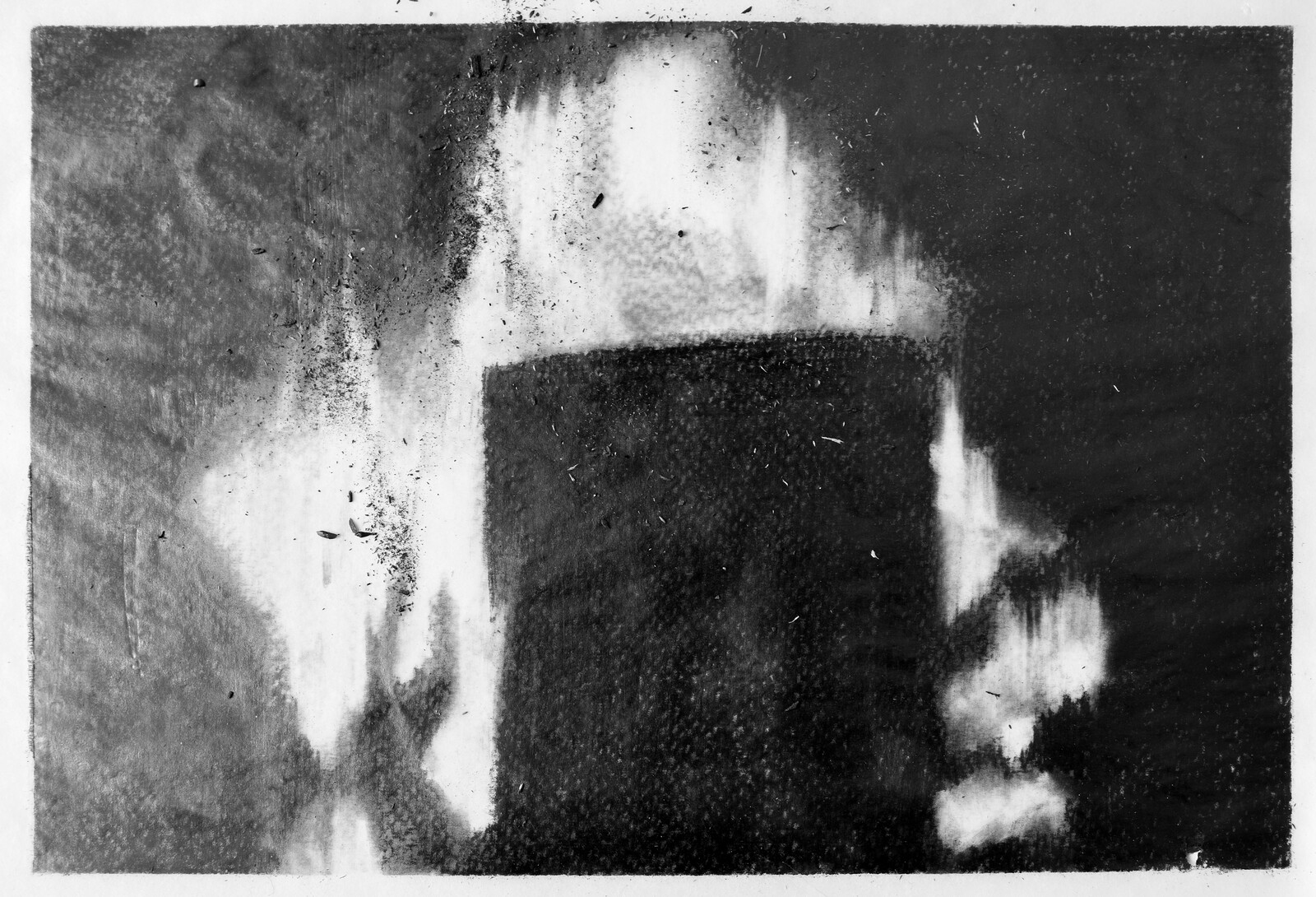

Ferenj: A Graphic Memoir in VR is an exercise of emancipatory thought in resistance to cultural domination, and othering. Using photogrammetry, I captured fragments of memory that aren’t typically seen through the lens of advanced technology. These everyday spaces of life and resistance—a corner store, local butcher, a fruit stand—form a counter-archive that works against the white-defined and imposed narrative of my intersectional, post-spatial identity.5 Instead, they present a narrative derived from snippets of memories and family stories; a narrative taken from what I knew to be true of Addis Ababa, and one that contains pride, hope, advanced technology, and a host of possible futures.

Ainslee Alem Robson and Kidus Hailesilassie, The Culture Archive, 2021, VR still.

Ainslee Alem Robson and Kidus Hailesilassie, The Culture Archive, 2021, projection mapping.

Ainslee Alem Robson and Kidus Hailesilassie, The Culture Archive, 2021, VR still.

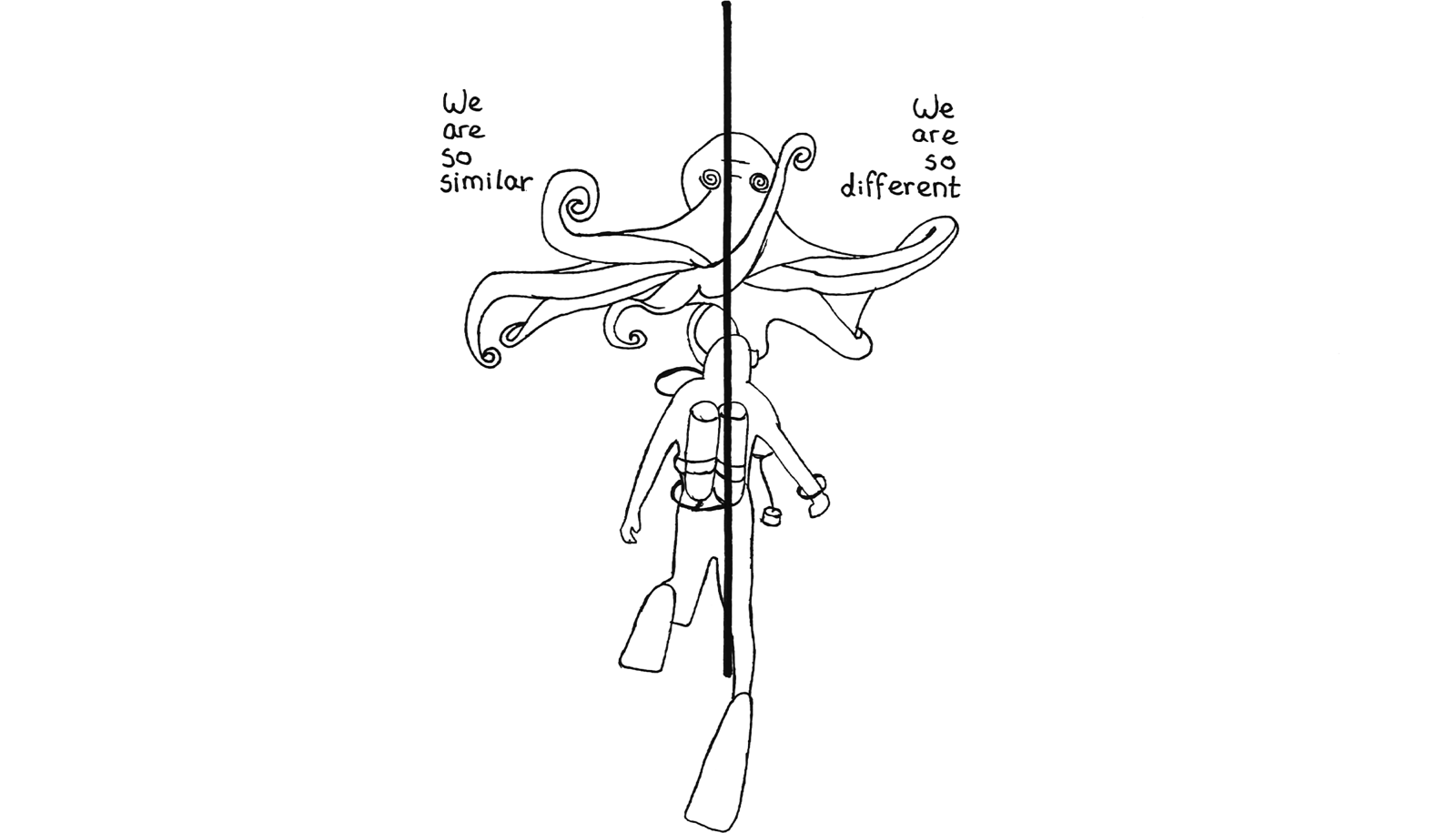

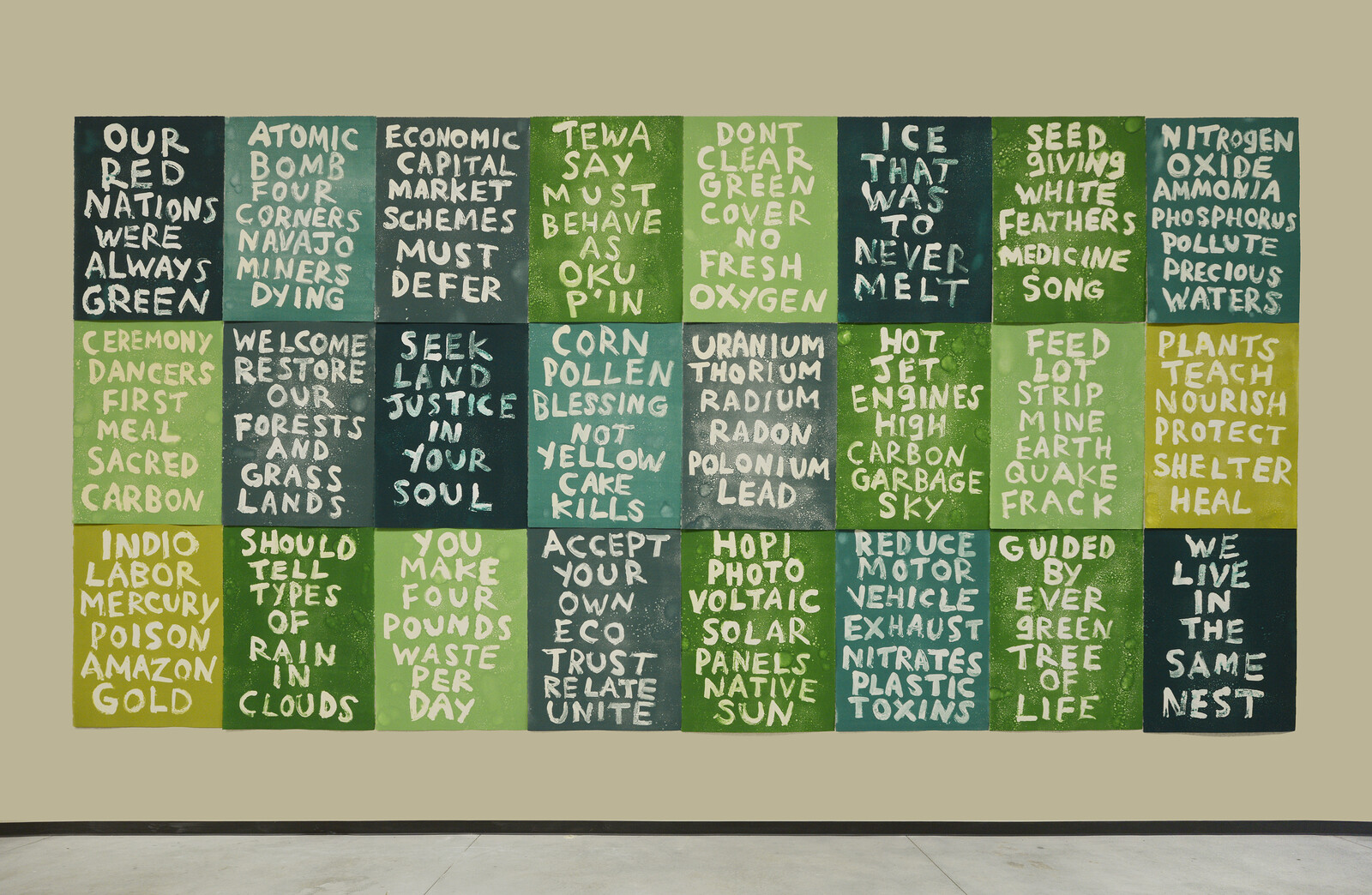

The Culture Archive, created in collaboration with Kidus Hailesilassie, recontextualizes the process of archiving Black consciousness, knowledge-generation, and technology through the lens of sankofa. The Ghanaian concept of sankofa refers to an ideograph from the Adinkra writing system which describes the process of bringing elements from the past into the present in order to learn from them and progress into the future. Emerging technologies such as AI and machine vision are placed at the heart of the narrative and technical world build to reframe alphabetic characters from indigenous African writing systems as vessels of African knowledge-generation, technology, and wisdom, and to allow the wisdom embedded within them to thrive in a new dimension.

“…natives must assert counterimaginings to create their authentic presence as what Vizenor calls postindians. Such imaginative self-recreation is accomplished primarily through storytelling because Indian was and is a stereotypic substitute for actual natives created by white storytelling…” Karl Kroeber, “Why It’s a Good Thing Gerald Vizenor is Not an Indian,” in Survivance: Narratives of Native Presence, ed. Gerald Vizenor (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2008), 29.

Term coined by Parisa Ahmadi, Ph.D. Candidate of Comparative Literature at the Ohio State University.

Tezeta was the soundtrack of my childhood as it was frequently played in Empress Taytu Ethiopian Restaurant in Cleveland, Ohio. Azmaris are poets who improvise verses while playing an instrument called the masenqo. They are lyrical storytellers who simultaneously critique and entertain society. They are living archives of oral history.

The origin story of coffee.

I am using Vizenor’s terminology to refer, in this case, to the fabricated reality and unbalanced perspectives produced by the White Gaze about Ethiopia, the continent, and Blackness.

Survivance is a collaboration between the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum and e-flux Architecture.