Welcome to the shores of Moreton Bay, just to the east of the sunny, sub-tropical city of Brisbane (or Meanjin, in the language of the Turrbal people), Australia. Our tour begins here at Brisbane Airport, on the reclaimed tidal mudflats at the mouth of the Brisbane River (Maiwar). This is the largest capital city airport in the nation, carrying on average more than 23.8 million passengers each year, conveniently located just opposite the Port of Brisbane, another significant cargo hub in the Asia Pacific region.

The land on which the airport is now situated is the suburb formerly known as “Cribb Island,” once home to many of Brisbane’s working poor—and the BeeGees—which was sacrificed at the altar of progress to make way for the jet-capable Brisbane Airport in the late 1970s. Sadly all that remains as a reminder of the area’s past is the ability to dine at the drolly-named Cribb Island Beach Club, located at one of the local airport hotels. If you’re game, try their house special, the “Cribb Island Burger.”

Before we move on however, we should remember this: while Brisbane is on “the Bay,” the Bay is not only of Brisbane. For the Quandamooka people, the Indigenous custodians of Moreton Bay, these unceded lands and waters are Quandamooka Country. Hugging the shores of Moreton Bay is a sprawling suburban region, encompassing the city of Brisbane and surrounding metropolitan governments. The bayside suburbs are connected and connective spaces; at an obvious level the ports link with national and international mobility hubs and global circuits of capital as passengers and cargo are ferried all over the world.

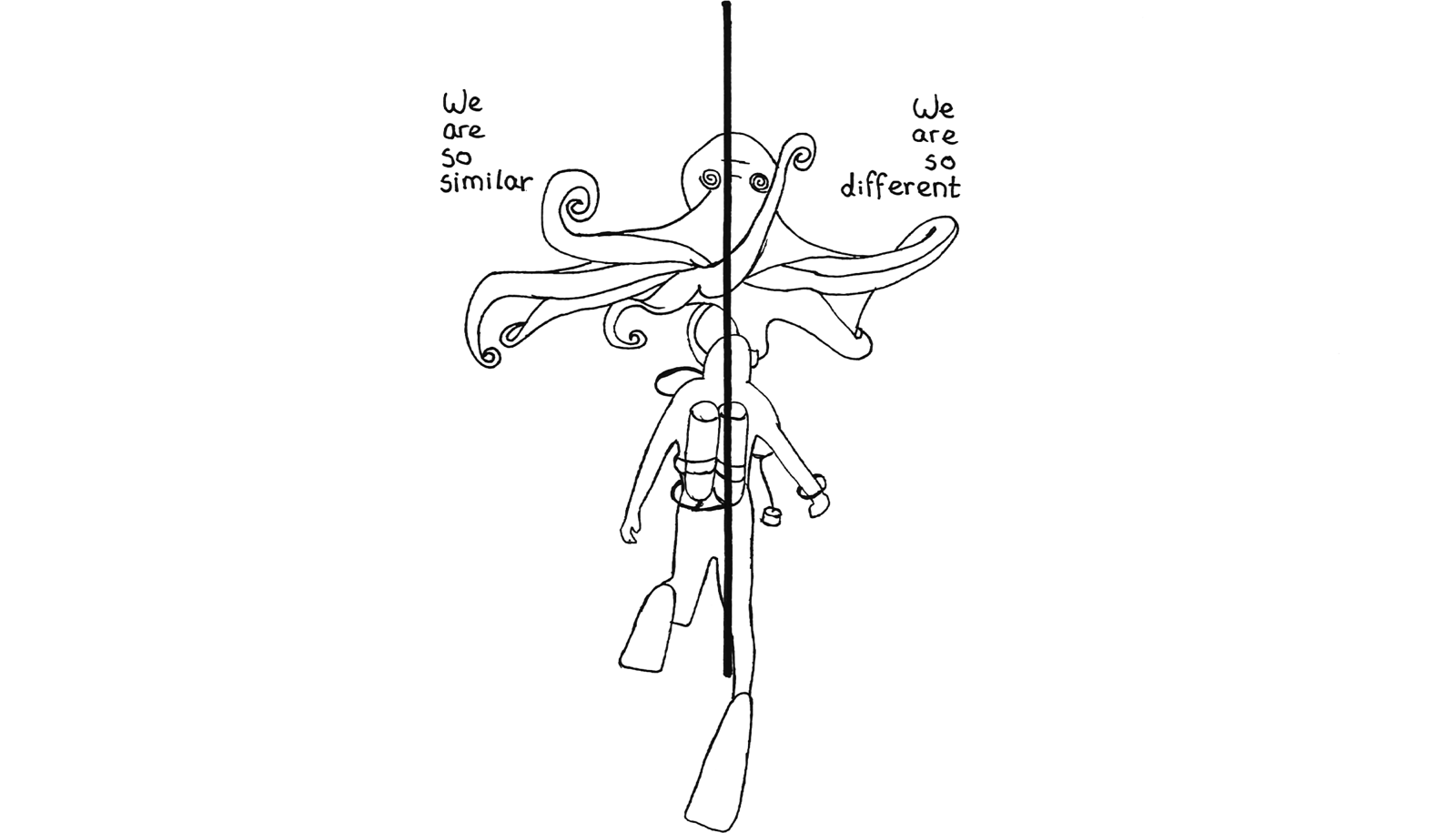

Yet the Bay is more than just a transit hub for the ever-expanding activities of the human population. It is, in fact, a hub for many highly mobile species: humpback whales, turtles, sharks, and migratory shorebirds—the “frequent flyers” of the nonhuman world. For the well-heeled Far Eastern Curlew, a bird that travels the distance of the moon and back in their lifetime, these shores are their overwintering home. If you look closely—you may have to squint to see them at the low-tide—you might glimpse a smattering of these tiny brown or greyish shorebirds that travel from here in the Antipodes right up to the Arctic on their annual migrations.

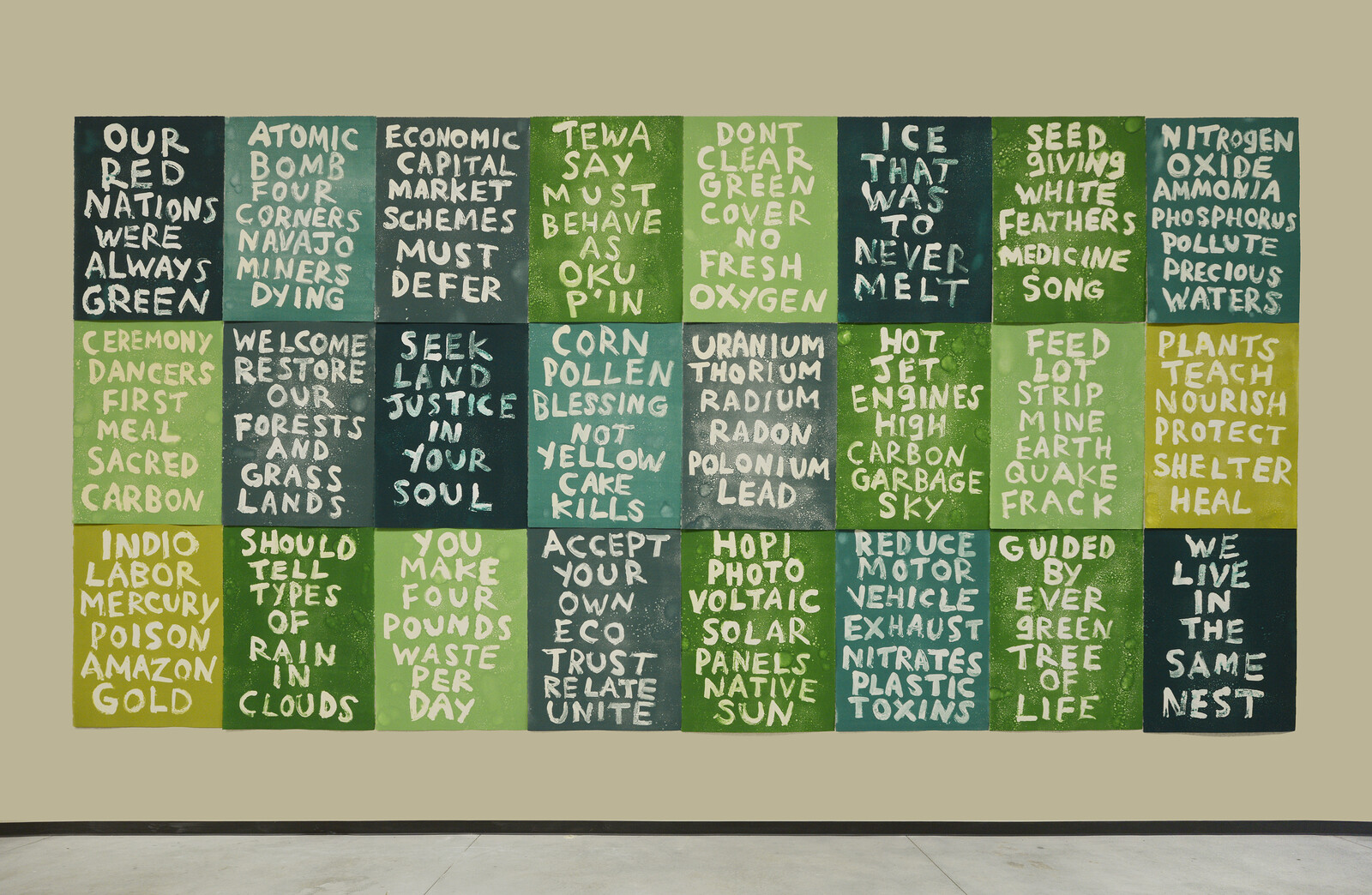

Watch your step. Around the back of the airport land are more ghosts of settlements past. Before there were oil refineries, air services, and sewage plants, the small bayside town of Pinkenba was home to agriculturally-minded European settlers. Myrtletown—a now defunct suburb, which was absorbed into Pinkenba—was renowned for its vineyards and market gardens, and most famous for its cauliflower crop. Settler-colonial families grew fresh fruits and vegetables, which were sent to Brisbane for sale, or further afield to support other forms of colonial expansion. Potatoes from Myrtletown were shipped north to feed enslaved Pasifika workers working the prolific sugar plantations in central Australia.

Little remains of this agricultural past—an industry also made possible by “reclaiming” the mudflats and mangroves—except for a historic schoolhouse that was the sign of a thriving local economy. Even less remains of the Aboriginal people upon whose land this bucolic idyll was built, with only the faintest traces of the violent encounters between European settlers and Indigenous inhabitants evident in a few place names: the name “Pinkenba” derives from the Turrbal “binkenba,” or “the place of the land tortoise.”

Sandwiched in between the carbon-intensive industries and industrial wastelands are a network of re-routed canals, artificial channels, and persistent mangrove pockets, all of which are monitored around-the-clock by security surveillance. An unlikely place for a thriving multispecies existence.

All sorts of things wash-up along these shores for our delight: organic, inorganic, microbial. If you look down, we find a duty-free bag, fish scales, sea glass that has been pummeled by the waves, tangled fishing line, and small bits of polystyrene. The ebbs and flows of the tides leave traces of mobility from elsewhere, evidence of an always connected shoreline being composed by ocean currents and trade winds. As geographers Kimberley Peters and Phil Steinberg remind us, “the ocean exceeds its material liquidity,” forging routes that bridge sea and land, and carrying the millions of humans and nonhumans along these long-haul travel corridors.1

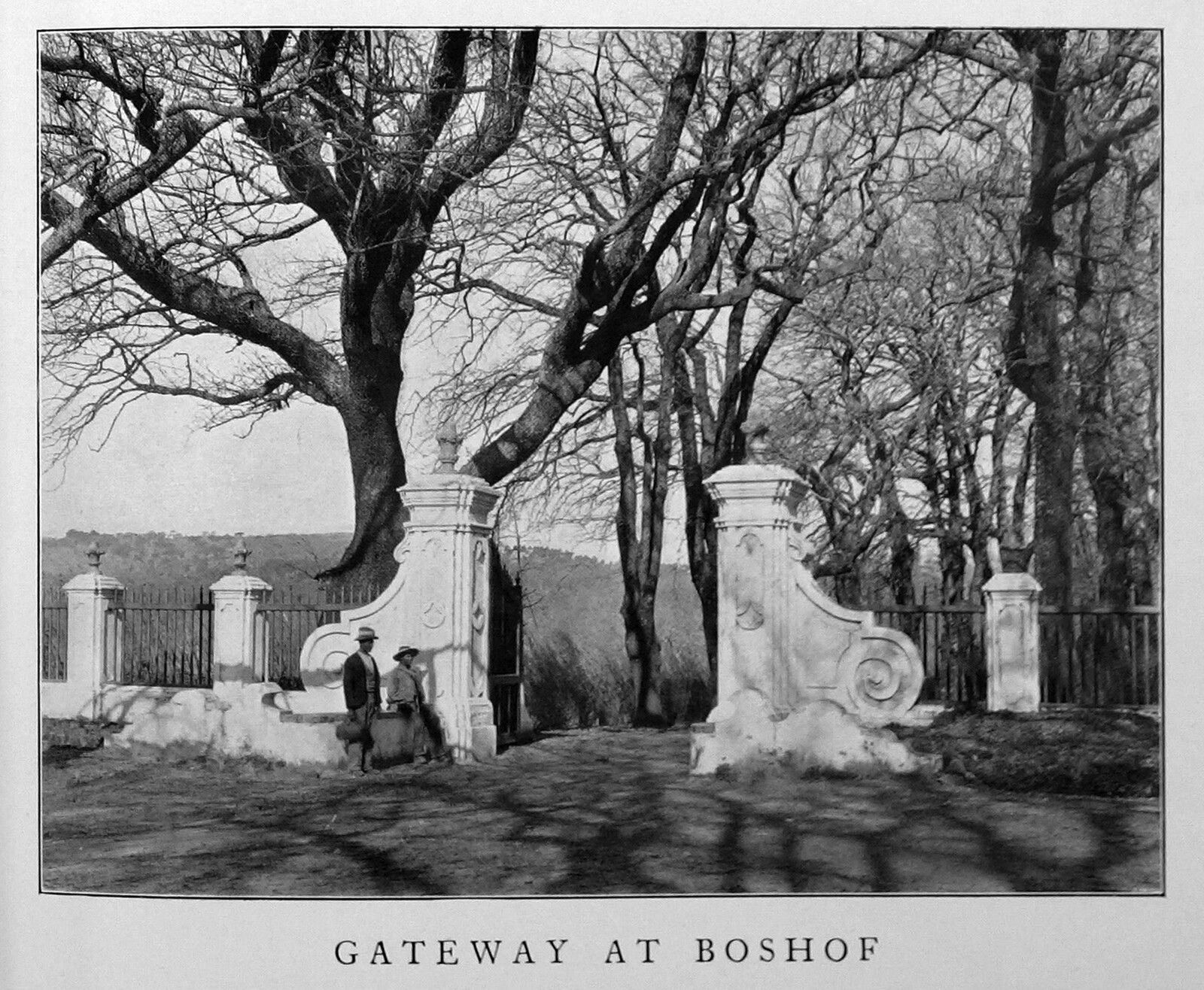

Today, we often think of global connectivity as a product of the jet aircraft. However, this little patch of creeks, mangroves, and mudflats has been deeply connected to the global political economy through multiple mobilities since colonization. Before the development of the first container terminal on the other side of the river, Pinkenba Wharf served as an important logistical hub of oceanic military force. Young colonial subjects embarked ships such as the SS Cornwall to fight with British forces in the Boer War. Decades later, global warfare imposed itself on the riverbank, with a sophisticated anti-submarine defense system being installed at Myrtletown. The concrete remnants of this defense remains, keeping a watchful eye over the river towards the oil refinery and container terminals.

On the other side of the inlet, we have Luggage Point, another location marked by its rich mobile heritage. It now houses the recently completed international cruise terminal, just around the corner from the city’s major sewage treatment plant. With all this technical know-how, experts have yet to do something about the smell: a heady mixture of salt air, wastewater, avgas, and mud hits as the breeze changes direction.

This vast port land is a geoengineering masterpiece, where the entire stretch of tidal wetlands was dredged and reclaimed over the past few decades. Eleven million cubic meters of sand were used to raise the ground above the flood line and sculpt this scenic location for each arriving flight.2 Since the first port expansions into the river delta and the reclamation of these tidal flats, the populations of avian visitors have dwindled, at first gradually, but now markedly. But the shorebirds’ heritage can still be admired in the cartography of these landscapes. The seaport’s arterial streets are named after migratory birds, and the names of the airport’s streets are a mixture of famous aircraft and coastal vegetation shrubs. Robert Smithson’s artistic designs for the Dallas-Fort Worth Regional airport are echoed here, where the carefully planned “landscape begins to look like a three-dimensional map rather than a rustic garden.”3 A curated authenticity pervades these functional, angular shorelines.

While this hypermobile landscape is marked by impervious terrestrial defenses—chain-link fence, barbed wire, biosecurity warning signs—and is under the watchful eye of the national security state, the terraqueous zone beyond the shoreline is subject to a different kind of scrutiny. A world away and several decades ago, nation-states came together to sign—and later ratify—the Ramsar Convention on Wetlands of International Importance Especially as Waterfowl Habitat of 1971. This mouthful of a treaty was the first international agreement to be directed toward environmental conservation, and one by which important wetland sites are putatively governed and protected.

Large swathes of Moreton Bay are home to migratory shorebirds and are designated Ramsar sites, meaning that local, state, and federal legislation and regulation must ensure the protection and conservation of these fragile habitats. Yet, the force of these designations dissolves into gesture, as developers and planners lobby decision-makers to gerrymander ecological systems, and engineers and environmental consultants insist that their administrative boundaries drawn on a map can ensure a clean separation between protection and extinction. At the very edge of Brisbane Airport, a little further beyond Luggage Point, migratory shorebirds travel thousands of kilometers for their annual layover. A perfectly straight line separates runway from “flyway,” and so long as the birds stay on the other side of that line, they can be counted and protected.

“Where to land?” the philosopher Bruno Latour asks, urging us to question of the scale of humanity and the impact of our mobilities on the planet.4 Surely when the winds are howling, the aircraft are in holding patterns, and the king tides are slapping at the remnants of the shoreline, these tiny wading shorebirds must also ponder this question.

After their long-haul journeys, the magnetic pull from one hemisphere to the next can only take them so far. These small patches of smelly, muddy shorelines along Moreton Bay offer a brief reprieve. When it’s low tide, you can feel the rumble of aircraft take-off and landing that reverberates across the mudflats. Local residents run, jump, and explore, accompanied by dogs, jetskis, and small fishing boats. Even such minor noises and disturbances send the timid shorebirds into a flurry, squawking and flapping. These momentary interruptions are a small but significant part of the pressures that many endangered species are facing, and these everyday actions entwine our futures with theirs. As we face common threats of rising seas, extreme weather and the fight for community space to inhabit along the coastlines, our “very coastal lives shadow those of the birds.”5

The ports along Moreton Bay are not their last port-of-call, but they are a significant piece of the future survival prospects for migratory species. Robert Smithson reminds us that an “airport is but a dot in the vast infinity of universes, an imperceptible point in a cosmic immensity, a spec in an impenetrable nowhere.”6 The infrastructures of human mobility are artfully overlaid on the habitat upon which these avian sojourners depend, almost as if we expect the shorebirds to see reason in the logic of progress and get on board. Protected zones are carefully inscribed on maps while the tumult of human progress bears down on the flight ways of species existence.7 Enjoy the view, while you can.

Kimberley Peters and Philip Steinberg, “The ocean in excess: Towards a more-than-wet ontology,” Dialogues in Human Geography 9, no. 3 (2019): 293–307.

Rachel Bronishon, “Brisbane’s New Runway: A timeline from conception to construction to completion,” BNE Brisbane Airport, January 5, 2021, ➝.

Robert Smithson, “Aerial Art (1969),” in The Writings of Robert Smithson, ed. Nancy Holt (New York: New York University Press, 1979), 92–93.

Bruno Latour, Down to Earth: Politics in the New Climatic Regime (Cambridge: Polity, 2018).

Andrew Darby, Flight Lines: Across the globe on a journey with the astonishing ultramarathon birds (Crows Nest: Allen & Unwin, 2020), 257.

Smithson, “Aerial Art (1969),” 92–93.

Thom Van Dooren, Flight Ways: Life and Loss at the Edge of Extinction (New York: Columbia University Press, 2014).

Survivance is a collaboration between the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum and e-flux Architecture.