Blackgirls young and old are memory keepers, cultural workers, love pillars, freedom mappers, and actors.1 Radical love is a regular praxis through which Blackgirls create spaces that center themselves and their community. Blackgirls have problematized the settler-colonial project of mapping and moved away from viewing space as an entrenchment of empire. Further, Blackgirls have spatially conceived of built environments as a strategy towards fostering sacred safety and deep social connections.2 Blackgirls’ creative, conceptual, and material placemaking illustrates our own liminality that allows us to (re)member, ritualize, and (re)imagine.3 While not typically viewed as architects, Blackgirls have a rich herstory of magically (re)claiming some of the most historically violent spaces, including farmland, homes, and even our very own kitchens, and converting them into sites for healing. Blackgirls practice love evangelism through unique spatial alchemy.4

Blackness, the physical and spatial embodiments of African Diasporic people that function under the system of racism and colonialism, has been traditionally cited under a white supremacist guise as both hypervisible and placeless.5 This leads to dominant empirical assumptions that Black geography lacks material referents and is defined by words rather than places, discourses, or dispossession.6 Traditional geography benefits from such ascriptions to Blackness as it reinforces the marginalization of difference through the systemic concealment of our physical, creative, and conceptual locations.7 Settler colonialism perpetuates this injustice by not plotting Black boundaries and spaces, which in turn forces Black people to use alternative methods of geography that fosters both their safety from displacement and connection to their communities.8 It follows, then, that womanist cartography becomes the process through which Blackgirls move through and relate to space physically and socio-politically. Equipped with this commitment to womanist cartography, we can unsettle hegemonic notions of memory, land, and sacredness more properly.9 Such a reorientation towards a womanist geography that traverses physical, virtual, and love space allows us to recognize that Blackgirls find liberation wherever we are.

Homeplace

The home has historically been the space where Blackgirls could feel most free. Our matriarchal homes are encumbered by Anti-Blackness and white supremacy. It was in our homes that we constructed a safe place where Black people could affirm one another and by doing so heal many of the wounds inflicted by racist domination. Working to create a home that affirmed our beings, our Blackness, and our love for one another was necessary resistance. Early innovators such have mapped and theorized spaces that Blackgirls create, reconfigure, and maintain in order to contend with and subvert the simultaneous forms of racist/white supremacist and heteropatriarchal violence and oppression to which they are often subjected.10 For instance, in her essay “Homeplace: A Site of Resistance,” bell hooks argues that the homeplace is a space in which Blackgirls who are marginalized by larger society are free not to be the intruder, the interloper, or the Other (as they often are outside of it). Instead, in the homeplace, Blackgirls are the standard, the norm, and the model by which all other things are measured. Homeplace is a space that is continuously forming and where roles and identities are chosen rather than assigned.

Within Black communities, the homeplace has been viewed as a domain of resistance to racism/white supremacy, but it is also experienced by many as a site that advocates for and sustains a heteropatriarchal arrangement of gender and sexuality. For many Blackgirls and Black queers, then, the homeplace has also been a space of violence and oppression that intersects with their experiences of oppression and violence in the larger society. In response to this, Black queer folx often create sacred homeplaces with chosen families that affirm every aspect of their racial, gender, and sexual identities.11 Blackgirl homeplaces allow us to have a necessary space for survival, meaning making, growth and self-definition.

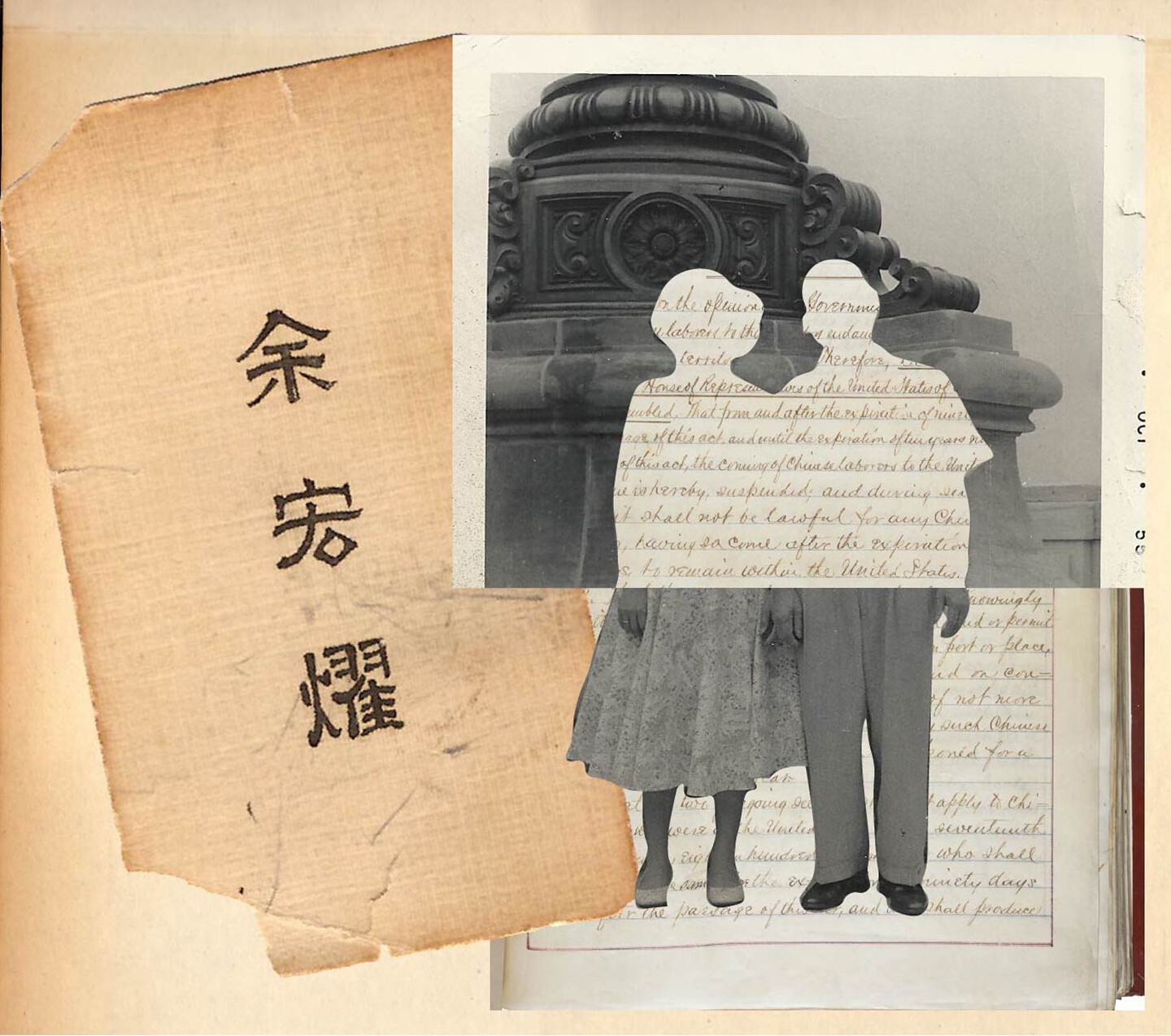

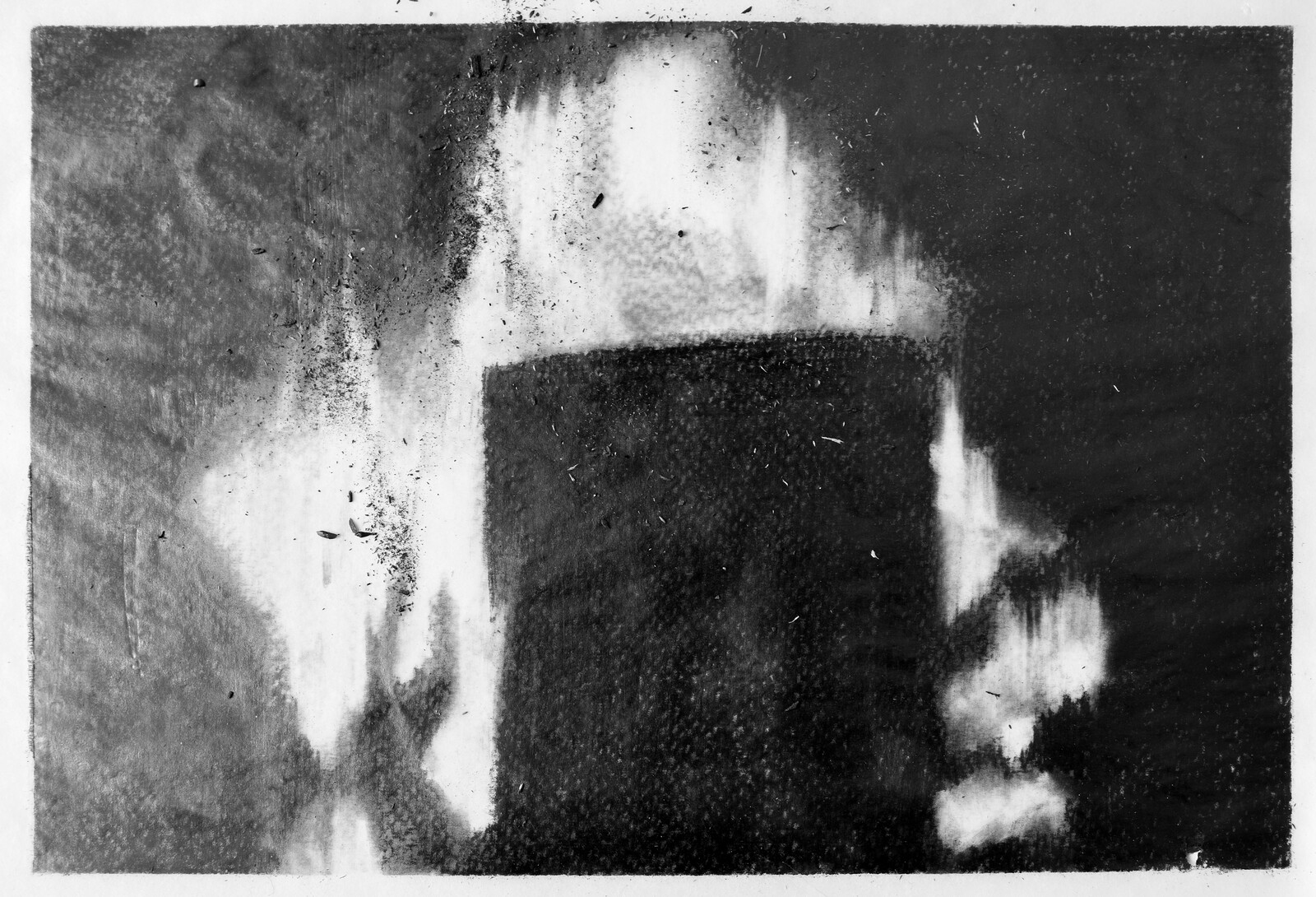

Loren Cahill, Loren’s Love Note Audio Collage, film still, 2021.

Porch/Stoop

The porch, or stoop, is an extension of the home. In its framed simplicity, the front porch/stoop has been a fixture in American life. Among African Americans it holds outsized cultural significance as a stage straddling the home and the street; a structural backdrop for observing your community and threats to your home. The porch/stoop is where Black folx gather to drink, sit, swing, and get their hair done. A natural place for convening and for healing, the porch/stoop is where you listen to yourself and to the stories of others. Zora Neale Hurston, a chronicler of Black Americana, understood the magic and necessity of the porch as a gathering place to witness and soak up herstory. Her prose cast the porch as a stage for storytelling. In Hurtson’s seminal Their Eyes Were Watching God, it was on the porch where Janie told her whirlwind saga of love and loss to her best friend Phoebe, in response to which, Phoebe said: “Ah done growed ten feet higher from jus’ listenin’ tuh you, Janie.”12

Black assemblies even on our own porches have often been considered threatening to authorities and white landowners. Many federally funded or Section 8 housing options regulate and penalize residents from gathering outside their dwellings under the guise of loitering laws. Porch/Stoop talks continue, however, to serve as a critical creative intervention, a space to gather to unpack and archive our memories. Porch/stoop talks are a vital act of Black defiance; a choice for community over isolation.

Kitchen

The kitchen table. Where Black mothers and daughters prep Sunday dinners on Saturday afternoons and each head of hair is pressed for Sunday’s church service. Where Black folx play vicious spades tournaments. Where we gather to eat, drink, share the latest gossip, and break down politics. The kitchen table physically and symbolically represents an inclusive space for Blackgirls to be seen, to be heard, and to just be. The kitchen table signifies the rich herstory of our foremothers and grandmothers who sat at the kitchen table where, beyond gossip and social talk, Blackgirls bore their souls and received healing and affirmation in the company of their sisters.

In 1980, womanist writers and activists including Audre Lorde and Barbara Smith started a publishing press for women of color called Kitchen Table: Women of Color Press. Given challenges faced with White-dominated journals, and particularly some White feminist journals, the press was created to provide publishing opportunities for the work of women, feminists, and lesbians of color. Naming the press “Kitchen Table” emphasizes the political act of women of color creating their own table when the dominant group denies them a seat at theirs. “The kitchen is the center of the home, the place where women in particular work and communicate with each other.”13 Each of these Blackgirls have harvested the power of the kitchen for our community’s good. The kitchen is a decolonial space to heal and empower.

Loren Cahill, Loren’s Love Note Audio Collage, film still, 2021.

#BlackGirlsAreMagic

Virtual space has also become vital for gathering, ceremony, and healing, especially amidst a global pandemic. Historically, hashtags developed as an informal method of highlighting ideas in unformatted text and growing conversation around a topic on social media platforms. The cultural, economic, political, and social presumptions of #BlackGirlsAreMagic inform other social media campaigns begun by Black queer femmes (i.e. #BlackLivesMatter, #SayHerName, etc.).14 It also furthers the necessity of projecting positive images of Blackgirls in a global society that would otherwise objectify, critique, and invisiblize the Black female body, mind, and spirit.15

Dominant narratives presented in media often use hetronormative metrics to construe Blackgirls as less than desirable, beautiful, or attractive. #BlackGirlMagic is a virtual space that counters the flawed dominant narrative that exalts white supremacy as definitive. It posits that since Blackgirls’ shared humanity has proven historically insufficient, then perhaps it is time to identify and moreover revel in what is distinctive, sufficient, and magical about Blackgirls. The opportunity to globally engage and witness the validation from Blackgirls is a unique spatial paradigm that could only be fostered with virtual quickness and ease.

Natural Hair YouTube

For decades, Blackgirls have been excluded from Western society’s normative definition of beauty.16 The glorification of European beauty standards in the media, and in particular straight hair, painted the narrative that our textured hair is not beautiful. This non-inclusive messaging projected the stereotype that natural hair and hairstyles like braids, locs, and twists are unkempt, unprofessional, and unworthy of being worn in public spaces.

If one were to ask many Blackgirls about how they learned to love the way their hair grows naturally, many of us would point to natural hair vloggers. Between 2008 and 2009, Blackgirl natural hair videos began to trickle onto YouTube, showing that textured hair was beautiful despite what society says. Within the past decade, the constant diffusion of natural hair content on YouTube has equipped Blackgirls like me with the knowledge needed to properly care for our curls and send a clear message to the world that natural hair should no longer be left out of conversations surrounding beauty. One of the most well-known Blackgirl hair care vloggers is Whitney White, better known to her YouTube subscribers as Naptural85, who has been sharing her secrets of maintaining healthy Type 4 curls since 2009. YouTube has become a virtual teach-in space for Blackgirls to feel comfortable in their hair, their skin, and with their beauty.

Blackgirl Verzuz

Verzuz competitions began in March amid the Covid-19 pandemic on Instagram Live. The event comprises two musical artists, groups, or producers—generally from the R&B or hip-hop sphere—battling one another in a song-for-song competition that lasts at least twenty rounds. Verzuz became a cultural phenomenon once Blackgirls entered the scene. On Saturday, May 9, 2020, the series finally showcased two women for a singers version: neo-soul sisters Erykah Badu and Jill Scott.17 The “battle” ended up flowing more like two friends having a loving listening session. About the event, journalist Naima Cochrane wrote: “[t]he night was a love fest; two friends and peers in music who genuinely admire and appreciate each other’s work trading stories. The ladies were much better about storytelling than previous participants have been. This match-up was a cultural win. It was music therapy; a salve for recent pain.”18 Jill and Erykah brought loving energy and open spirits to the first women’s battle in the spirit of sisterhood.

Brandy and Monica also participated in a Verzuz showdown on August 31, 2020, reuniting twenty-two years after their R&B hit, “The Boy Is Mine.” They made note that, although they had collaborated in the past, this was their first time speaking in over eight years. They had a mediated conversation prior to the battle to assuage hurt feelings from their previous relationship. The singers infused poetry and gave background herstory to their songs and production. They disclosed that they began singing as preteens at ages twelve and fourteen. At its peak, the web broadcast drew 1.2 million simultaneous viewers, the highest recorded among the series thus far. Twitter’s global director of culture and community God-is Rivera wrote about the event that the battle reminded Blackgirls of “music that we had our first crushes to, songs that we fell in love with, songs that healed us through heartbreak and songs that offer a vision of ourselves.”19 Blackgirls offered us the blueprint to turn music into a virtual platform into a ceremony for love, healing, and cultural celebration.

Love Space

Blackgirls have long been searching, creating, and protecting their plots in the struggle for racial and gender justice. M. Jacqui Alexander finds it imperative that we engage in “crafting interstitial spaces beyond the hegemonic where feminism and popular mobilization can reside.”20 Doing this “would mean building…a meeting place where our deepest yearnings for different kinds of freedoms can take shape and find rest.” In love space, Blackgirls of all ages can be a mother, daughter, and a sister. In love space, collective, cultural, and creative memories are unleashed to connect us directly with our ancestors. Love space ritualizes work, play, and food. Love space allows our imaginations to be Black, radical, ratchet, and to live in the boundless territory of Afrofuturism. Love space is physical, virtual, and ethereal. Love space allows Blackgirls to explore their own radical love, both collective and individual, allowing them to remember, ritualize, and reimagine it in a manner that leads us all toward direct transformation. Love space is the Blackgirl nexus for affective potential, interaction, and interdependence. This radical act of loving spatial creations allows us to begin to create a new world. Whether we start in our homes, online, or lead with our hearts, its transgression is forever mapped onto the spaces we make for ourselves.

See: Robin M. Boylorn, “On Being at Home with Myself: Blackgirl Autoethnography as Research Praxis,” International Review of Qualitative Research 9, no. 1 (2016): 44–58; Ruth Nicole Brown, Hear Our Truths: The Creative Potential of Black Girlhood (Champaign: University of Illinois Press, 2013); Saidiya Hartman, Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments: Intimate Histories of Social Upheaval (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2019); bell hooks, Sisters of the Yam: Black Women and Self-Recovery (Boston: South End Press, 1993); Jennifer C. Nash, “Practicing Love: Black Feminism, Love-Politics, and Post-Intersectionality,” Meridians 11, no. 2 (2013): 1–24; Alice Walker, In Search of Our Mothers’ Gardens: Womanist Prose (San Diego: Harcourt, 1983).

Chinyere Okafor, “Black Feminism Embodiment: A Theoretical Geography of Home, Healing, and Activism,” Meridians 16, no. 2 (2018): 373–381.

Marcus Anthony Hunter, Mary Pattillo, Zandria F. Robinson, and Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor, “Black Placemaking: Celebration, Play, and Poetry,” Theory, Culture & Society 33, no. 7–8 (2016): 31–56.

ThisisSignified, “SIGNIFIED: Alexis Pauline Gumbs,” YouTube, September 7, 2012, ➝.

See: Henry Louis Gates, Jr., “Introduction,” in Black Cool: One Thousand Streams of Blackness, ed. Rebecca Walker (New York: Catapult, 2012); Kiese Laymon, How to Slowly Kill Yourself and Others in America (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2020); Mychal Denzel Smith, Invisible Man, Got the Whole World Watching: A Young Black Man’s Education (New York: Bold Type Books, 2016).

Katherine McKittrick, Dear Science and Other Stories (Durham: Duke University Press, 2020).

See: Marcus Anthony Hunter and Zandria F. Robinson, Chocolate Cities: The Black Map of American Life (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2018); Otherwise Worlds: Against Settler Colonialism and Anti-Blackness, eds. Andrea Smith, Tiffany Lethabo King, and Jenell Navarro (Durham: Duke University Press, 2020).

See: Brandi Thompson Summers, Black in Place: The Spatial Aesthetics of Race in a Post-Chocolate City (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2019); Ashanté M. Reese, Black Food Geographies: Race, Self-Reliance, and Food Access in Washington, D.C. (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2019).

See: M. Jacqui Alexander, Pedagogies of Crossing: Meditations on Feminism, Sexual Politics, Memory, and the Sacred (Durham: Duke University Press, 2005); Katherine McKittrick, Demonic Grounds: Black Women and the Cartographies of Struggle (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2006).

See: Patricia Hill Collins, Black Sexual Politics: African Americans, Gender and the New Racism (Milton Park: Routledge, 2004); bell hooks, “Homeplace (A site of resistance),” in Yearning: Race, Gender, and Cultural Politics (Boston: South End Press, 1990), 41–49.

Okafor, “Black Feminism Embodiment.”

Zora Neale Hurston, Their Eyes Were Watching God (Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott, 1937).

Barbara Smith, “A Press of Our Own Kitchen Table: Women of Color Press,” Frontiers: A Journal of Women Studies 10, no. 3 (1989): 11–13.

See: Satoshi Kanazawa, “Why Black Women Are Less Physically Attractive Than Other Women,” Psychology Today, May 16, 2011 (article has been redacted due to controversy); Akiba Solomon, “The Pseudoscience of ‘Black Women Are Less Attractive,’” Colorlines, May 17, 2011, ➝.

See: Maxine Leeds Craig, Ain’t I a beauty queen?: Black women, beauty, and the politics of race (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002); Tamara Winfrey Harris, The Sisters Are Alright: Changing the Broken Narrative of Black Women in America (San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler Publishers, 2015); Noliwe M. Rooks, Hair Raising: Beauty, Culture, and African American Women (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1996).

Joshua Espinoza, “Stream Jill Scott and Erykah Badu’s ‘Verzuz’ Battle,” Complex, May 10, 2020, ➝.

Naima Cochrane, “Jill Scott vs. Erykah Badu ‘Verzuz’ Battle of Neo-Soul Titans: See Billboard’s Scorecard and Winner For the Showdown,” Billboard, May 10, 2020, ➝.

God-is Rivera (@GodisRivera), “I hope after tonight folks really understand and appreciate what Brandy and Monica gave to young Black girls in the 90s. They gave us songs to have our first crushes to, songs to fall in love to, songs to get thru our first heartbreak. They gave us a vision of ourselves #Verzuz,” Twitter, August 31, 2020, ➝.

Alexander, Pedagogies of Crossing.

Survivance is a collaboration between the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum and e-flux Architecture.