Superimposed memories in the soil of postcolonial Korea

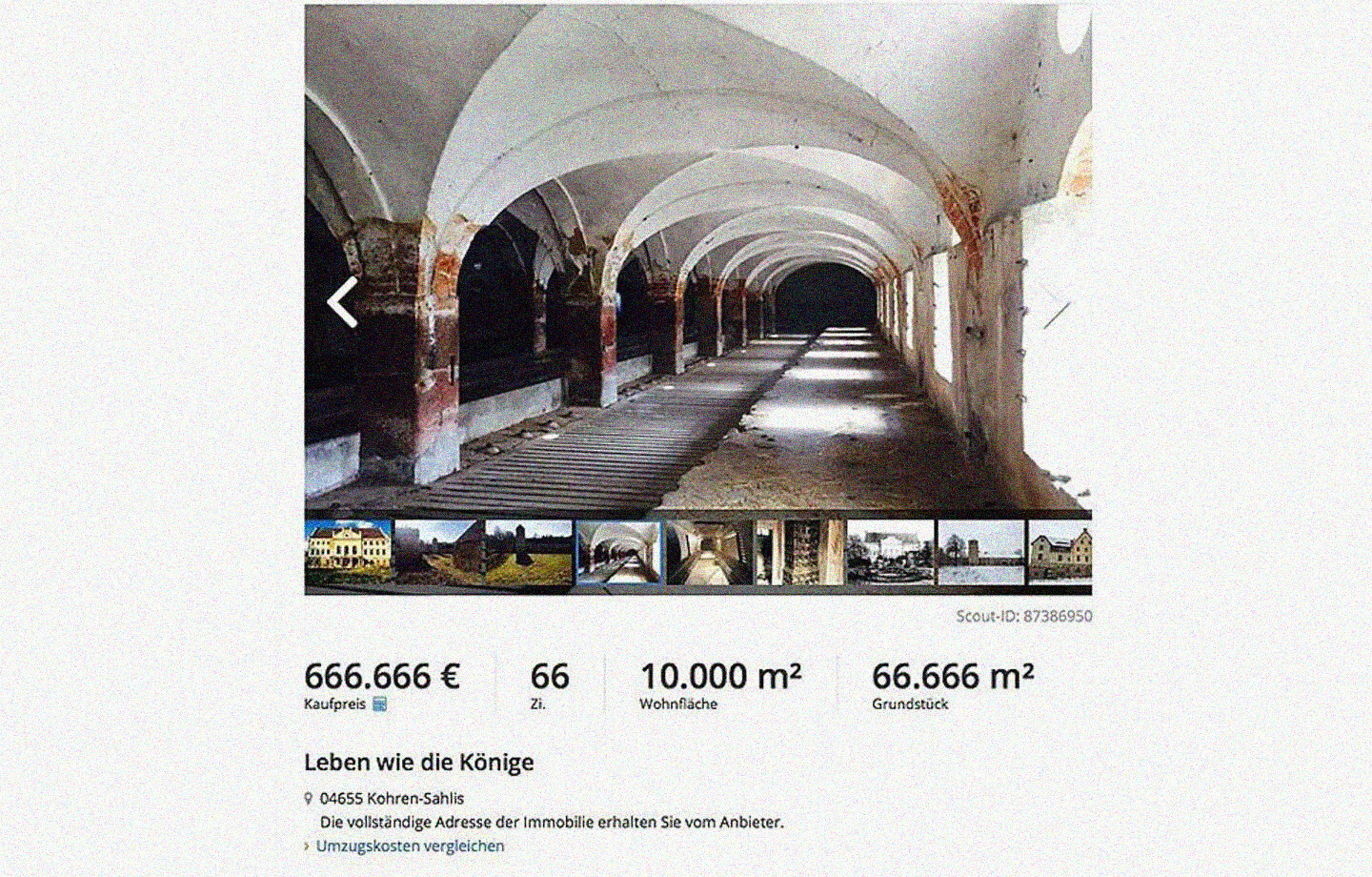

In 1936, amidst the Japanese occupation of Korea, a Japanese kaibatsu corporation called Maruboshi started to build residential areas and stables near the Daegu train station, within which there was a collective village named Maruboshi, near Chilseung-dong.1 From colonial liberation in 1945 to the end of Korean War, Maruboshi filled with refugees fleeing to South Korea, transforming into a vibrant topos of commoners’ life. After the rapid introduction of modernity and industrialization during Park Chung-Hee’s military regime (1961–1979), traces of Maruboshi’s colonial past, from its facades to collective wells, started to disappear and be replaced by western-style apartment complexes. Instead of refugees or colonial subjects, these apartments were designed for and marketed towards laborers who dreamt of a bourgeoisie middle-class family life for themselves. As a metonym for a compressed modern history of Korea, in 2016 this multi-layered urban palimpsest was completely demolished to reveal its bare and wild face, waiting for another space of residence to be built on top again.

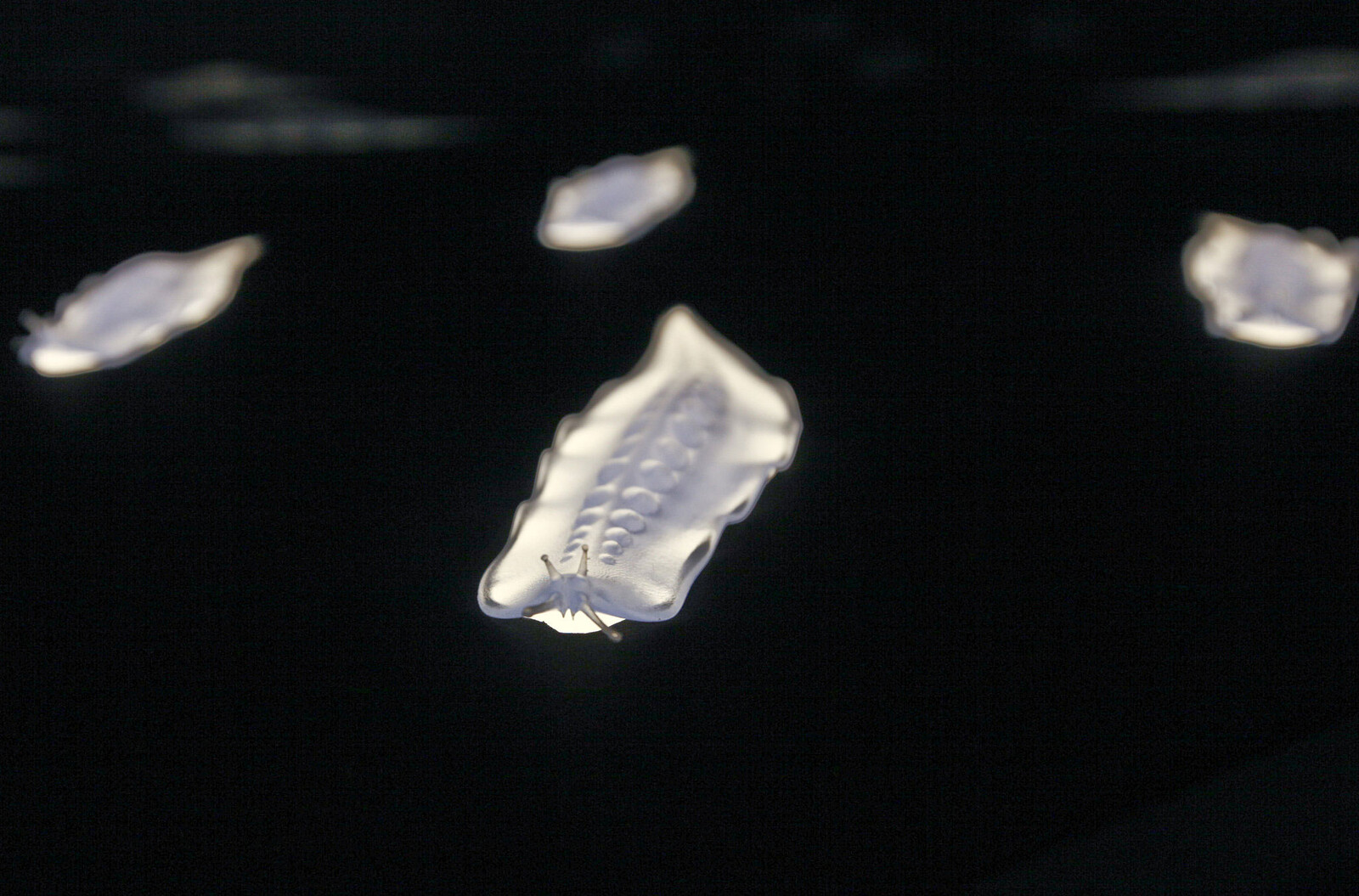

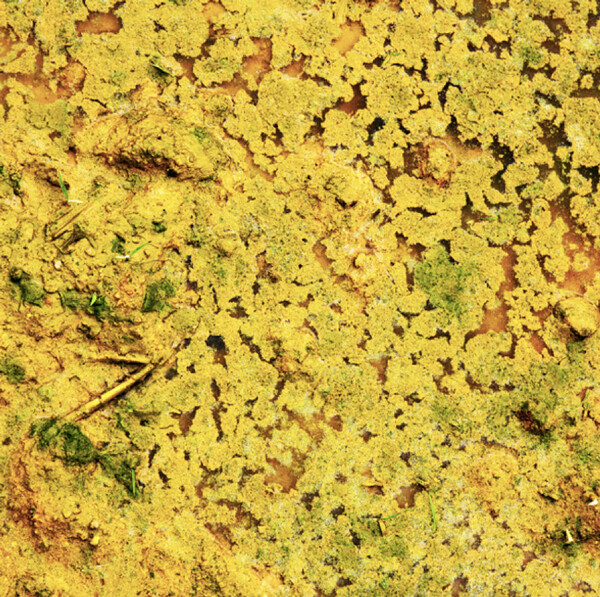

The gaemangcho (Erigeron Aannuus), a biennial North American plant species with white daisy flowers, was first brought into Korea when the Japanese empire built railways as part of colonial modernization. Apart from its humble appearance, the plant soon came to represent the loss of national sovereignty among Koreans, and was often referred to in a derogatory way such as MangGukCho (nation-ruining plant) or Oepul (Japanese plant). The seeds of gaemangcho, first buried deep below the colonial Maruboshi eighty years ago, flourish today. The ephemeral forest that has come to cover the barren sites of Maruboshi germinates according to the concealed structure of a disjointed modernity. Recall Gramsci’s remark on the interregnum, on the disjunction of time and space as a symptom of contemporaneity: “The crisis consists precisely in the fact that the old is dying and the new cannot be born: in this interregnum a great variety of morbid symptoms appear.”2 This ghostly return of the “have-lived things” permeates into life as an uncanny cartography of modernity.

There is a primitiveness to a foreign plant species’ profuse sprouting. The gaemangcho in Maruboshi presents us with self-reflexive questions about Korean modernity through the materialization of aboriginality and non-human diaspora. This essay is a reflection on postcolonial Korean modernity that interrogates the articulation of speciesism as a racist metaphor, the discourse of animality and the pervasion, representation and sovereignty of non-human species both during and after the colonial period in Korea. It attempts to allow for cultural translation across and beyond issues of anthropocentrism and postcolonial modernity, not only at the level of narrative or convention, but also on the level of a specifically non-human, postcolonial, modern condition.

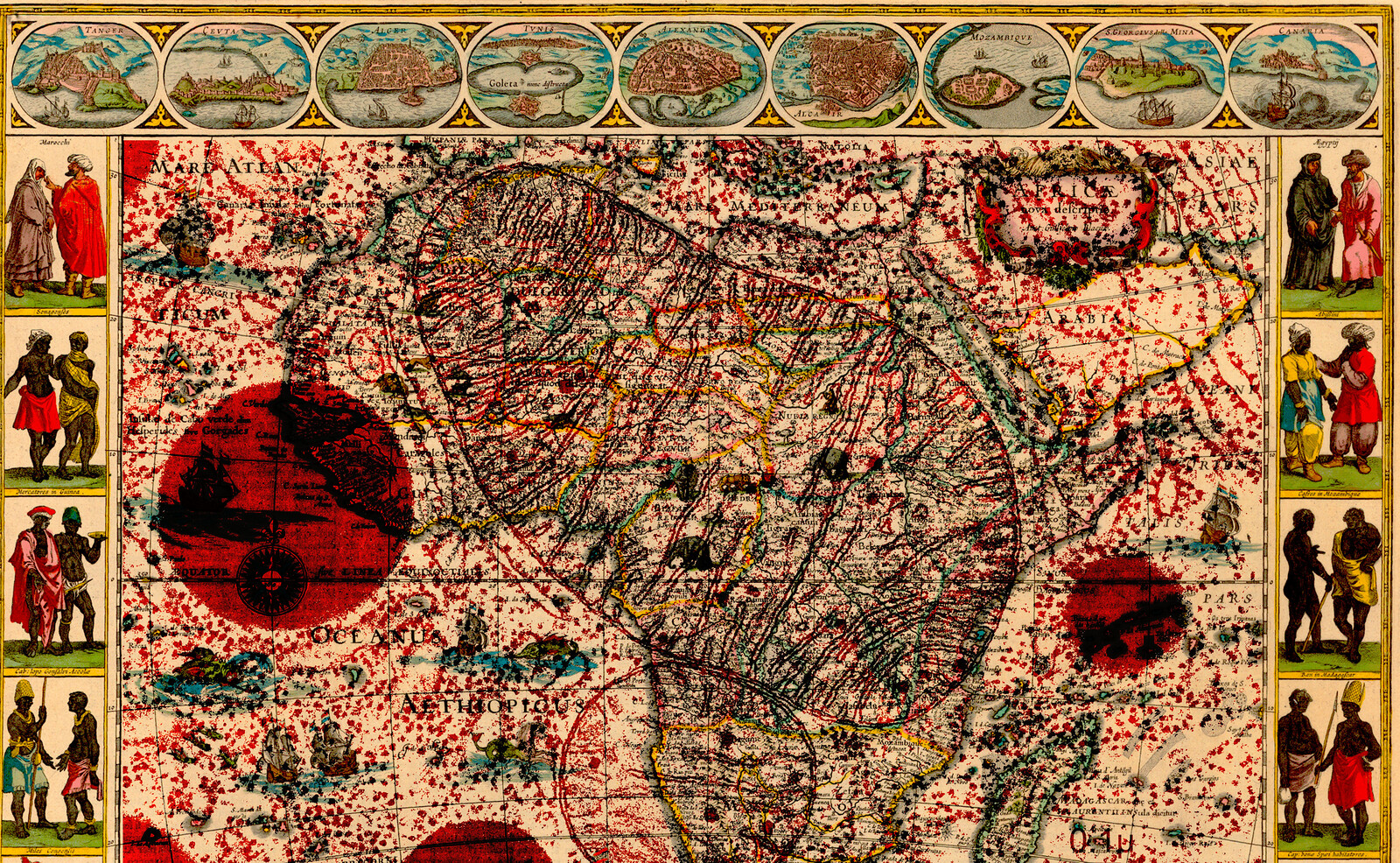

Above: Map of Daegu/Taikyu right after the colonial redesigning by Japanese empire circa 1910. Below: Postcard, Views of Bukseongno in Daegu/Taikyu in 1920s.

The Return of the Primordial and the Recursive Questions of Colonial Memory

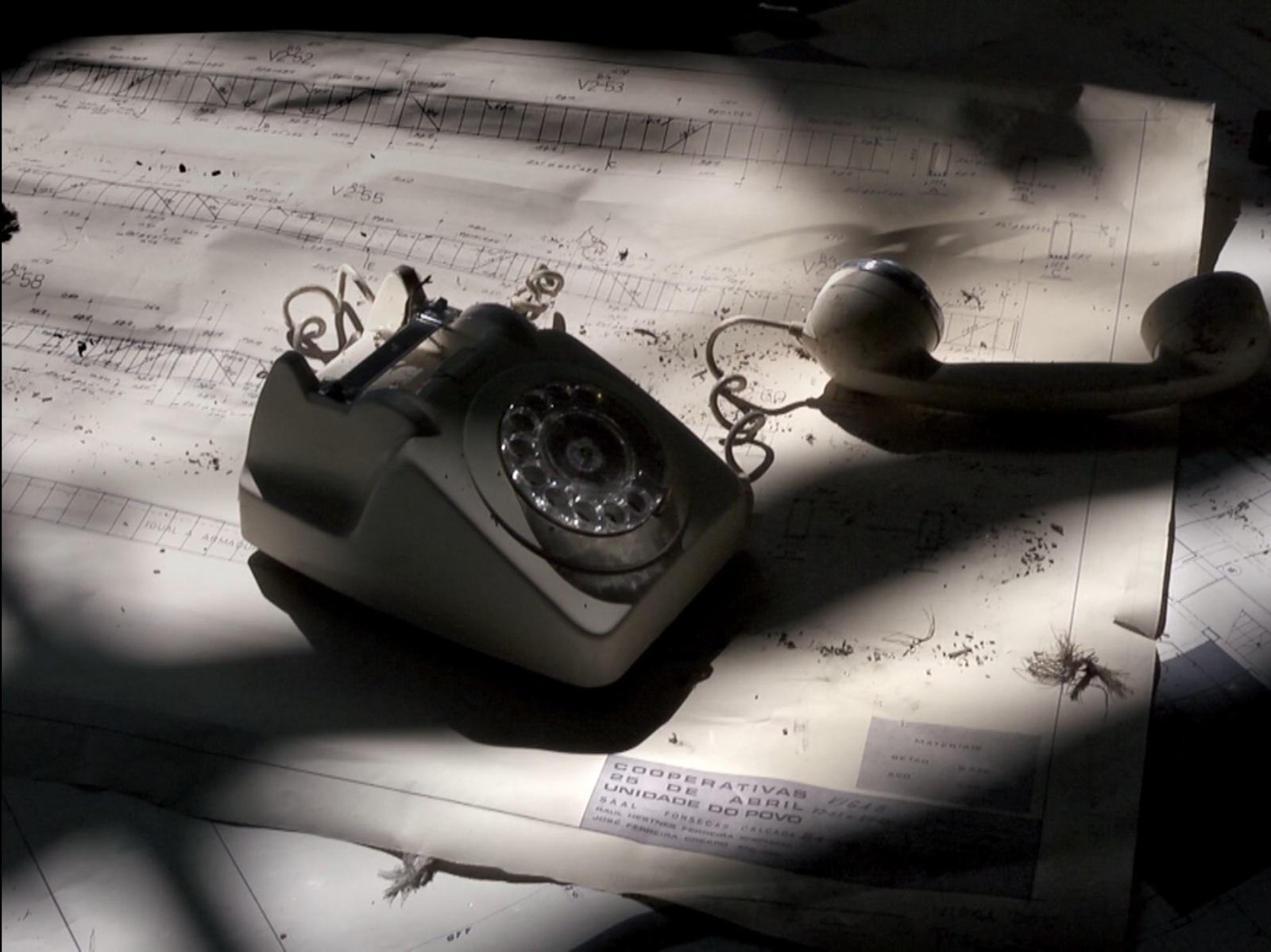

The return of the primordial encompasses a narrative of time’s bifurcation, of the past and the present, and as such has been deeply rooted in the space where we once stood. The modern self, having been enamored with the apparatuses and tropes of modernity (read: uniformity and hybridity), is now reeling from the uncanny symptoms summoned by the return of the have-lived.

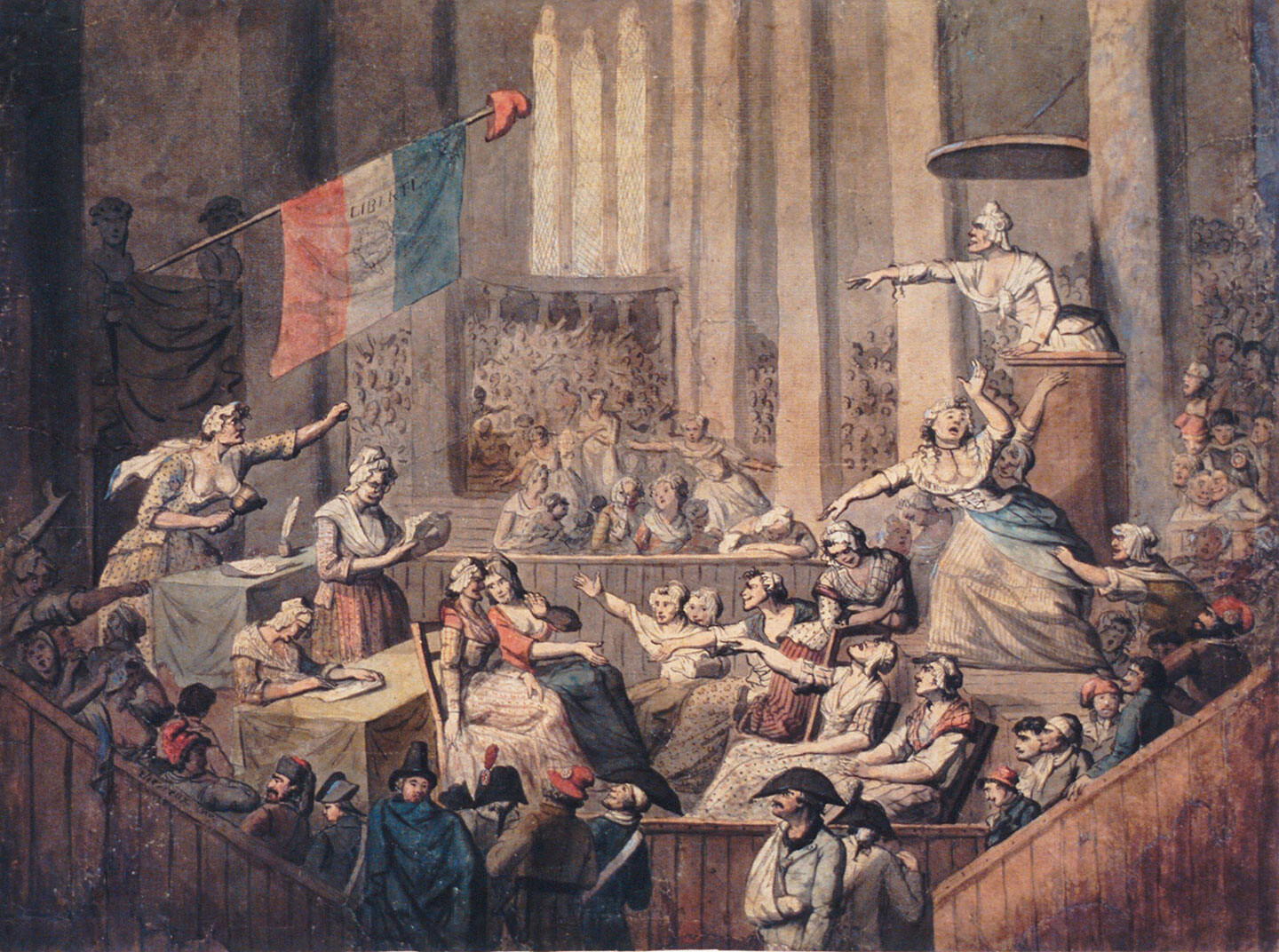

Postcolonial life is full of contradictions and paradoxes. At a conscious level, the post-colonized reject the knowledge, both past and present, inherited from the colonizer. But the colonizer has reorganized itself as part of the global capitalist system, thus making its shadow impossible to escape. Furthermore, if we accept Yoshimi Takeuchi’s observation that the East could not have recognized itself without the West’s invasion, then non-Western and/or Asian modernity acquired self-consciousness only through the recognition of the West, and specifically as its Other.3 Postcolonized Koreans roam around inside the prison yard of imperialist mantra, burdened with symptoms of our incommensurable colonial legacy and absence of autonomous self-recognition and self-reflection. Asia’s process of nation-state building is a phantasmagoric maelstrom of postcolonial cartography, where the cultural discourse on racial and ethnic diversity wears the skin of anthropology and the debris of the colonial unconscious is superimposed on the logic of industrialization and the identitarian impasse inherent to modernization. In such a world, how do we experience multiple modernities? Is it possible to resurrect, bring back to life the presence of primordial and animistic spirits that were thought to be killed long ago?

Let us forget, for the time being, the discourse of unknown places, indeterminacy, the biological body, life, and nature. The primordial, as represented by gaemangcho, has always been around in many manifestations. It can be found in the chaotic noise of the city as it rumbles; in the quiet flowering of weeds by the suburban roadside; in a midsummer’s night swarm of insects by the river bank. There is the story of dead mayflies found in heaps below glittering storefront windows.4 Similarly, there is the story of how the nutria came to Korea.5 These stories are signs of rupture in an unconscious silence about the forgotten world that was once full of animistic magic. They allow us to unmask a story of modernity as a symptom of an ever-present colonialism wrapped in capitalist phantasmagoria.

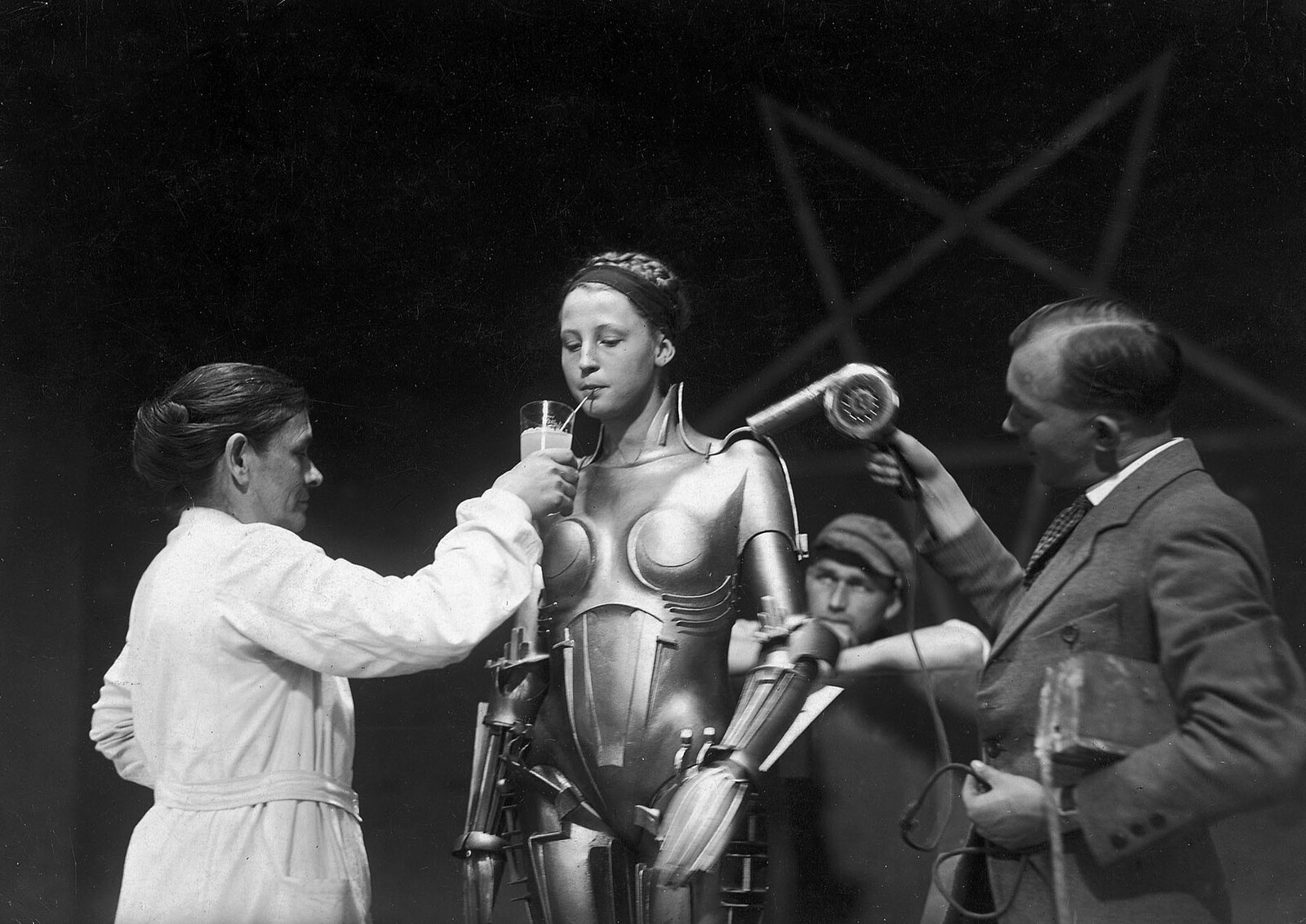

If Benjamin’s philosophy on the repetition of cultural history was centered on the ways in which an original thing is produced in a certain moment of history and how it contains the possibility of its reproduction within time, then Korea is a site for the “afterlife” of colonial modernity. Buck-Morss elaborates on this when she illustrates Benjamin’s fascination with a female wax figure, saying “her ephemeral act is frozen in time. She is unchanged, defying organic decay.”6 Constantly querying acts of remembrance, the gaemangcho is a cultural embodiment of a particular historical moment.

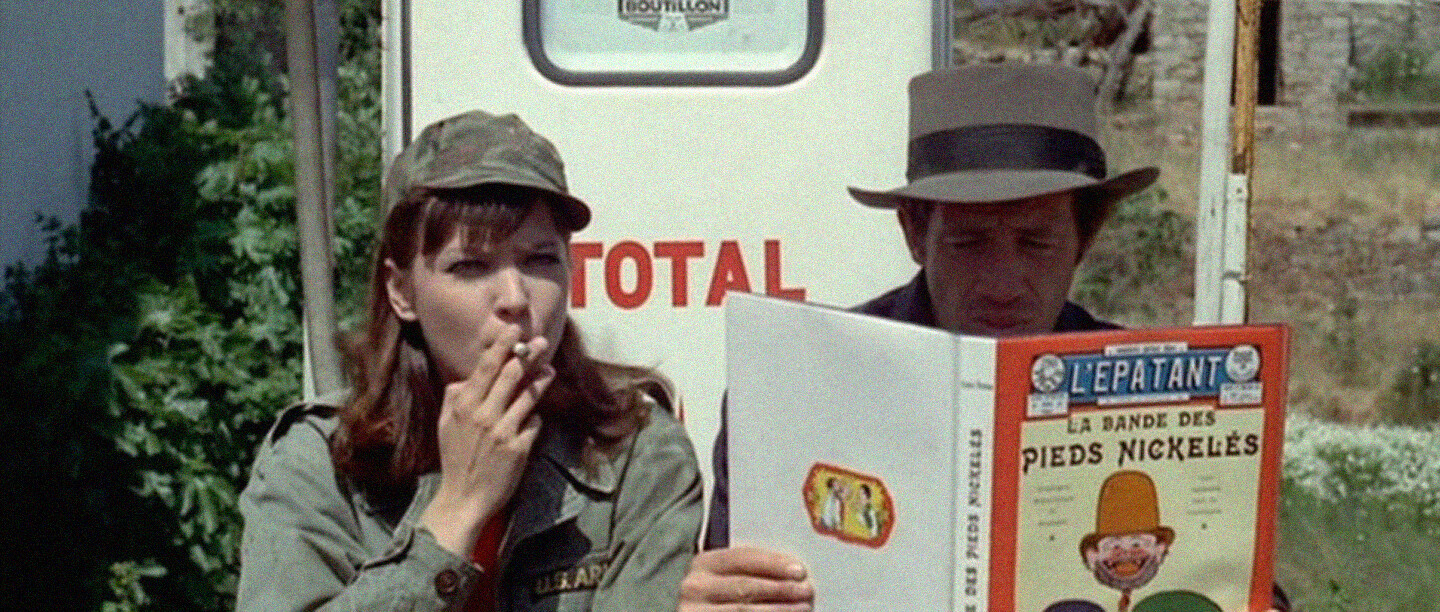

Film stills from Pom Poko (平成狸合戦ぽんぽこ), a Japanese animated film directed by Isao Takahata, Studio Ghibli, 1994.

Ever Present Past as Colonial Phantoms

The spine of colonial tropes and analogous scientific discourses in East Asia that have caused xenophobia, collective fear and a psychology of victimhood are closely linked to a particular form of Japanese anthropology that was “invented” as an imperialistic strategy against the Orientalism inherent within its Western variant.7 Anthropology as a discipline under Imperial Japan constructed a Japanese identity in dialectical opposition to Korean and other Asian Others. Micronesians, for example, became the “lazy Other”; Koreans, Taiwanese, the Ainu in Japan and the indigenous people of Taiwan became “them,” not “us.” Through various discourses on race, gender, and pseudo-science, Imperial Japan reorganized Asia’s epistemological topography with the colonial logics of inclusion and exclusion, and in so doing, secured their position as the superior Asian, as the one that was “almost white but not quite.”8

However, since colonial liberation, such differentiation amounts to no more than the narrative of the ethnic abjection.9 The question thus remains: after the fall of the Japanese Empire, how do the discourses of colonialism and pseudo-science remain as a historical trauma within Korean society? How did the internalized rhetoric of mono-ethnic nationalism and the mimesis of colonial imperialism come to represent South Koreans’ memorable—as well as forgettable—wounds?

The body of South Korea has experienced rhetorical plagues with the enchanting but humiliating ambivalence between discourses of victimhood, the circulation of colonial modernity/mentality, the sorcerous conjuration of both anti-communism and fascism, the invention of the North Koreans as the non-human animal “Other” and a compressed version of twentieth century modernization.10 The prosthetic modernity embedded within the colonial memories from two Empires, Japan and the US, caused postcolonial pathology in which the South Koreans incessantly imitate the imperialists’ logics while underestimating themselves and limit their own possibilities.

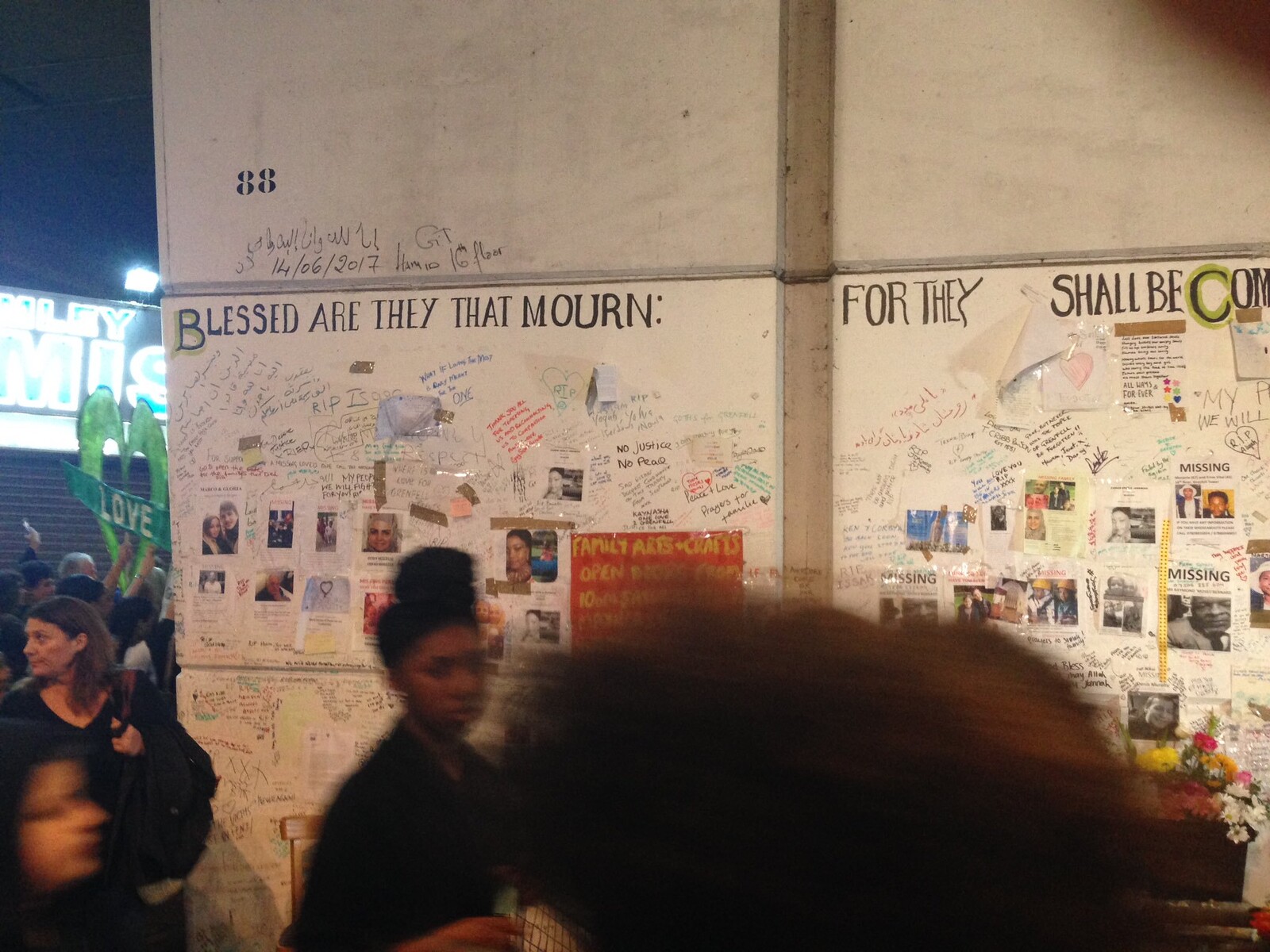

If the metonymy of interregnum, which Gramsci describes as an intermediate state between life and death, could be applied to the recent Sewol ferry incident,11 we can find evidence of a “hypertrophy of memory,” from both within the art world and its treatment of the politics of mourning and the spheres of mass media and popular culture.12 “Colonial memory” is an epistemological and ontological problem for the question of bare life and the right to live. In the context of Korean modernity, the crucial aspect of the interstitial returns through the Sewol ferry incident, in that it posed the following questions: “Who counts as human? Whose lives count as lives? And what makes for a grievable life?”13 It is precisely the reification of multiple modernities that fissure and rupture the cognitive topography of modernity and allow these questions to be asked without clear answer.

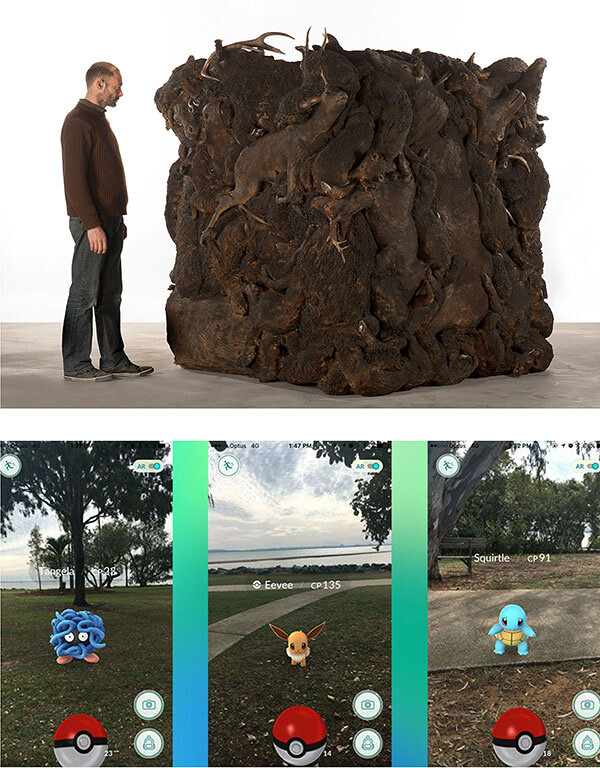

Above: Adel Abdessemed, Who’s Afraid of the Big Bad Wolf, 2011-2012. Photo: Vaga. Courtesy of David Zwirner Gallery, New York. Below: Pokémon GO is location-based augmented reality game developed by Nintendo, which became a global phenomenon and one of the most profitable mobile apps of 2016.

The Non-Human and Animal Subjectivities

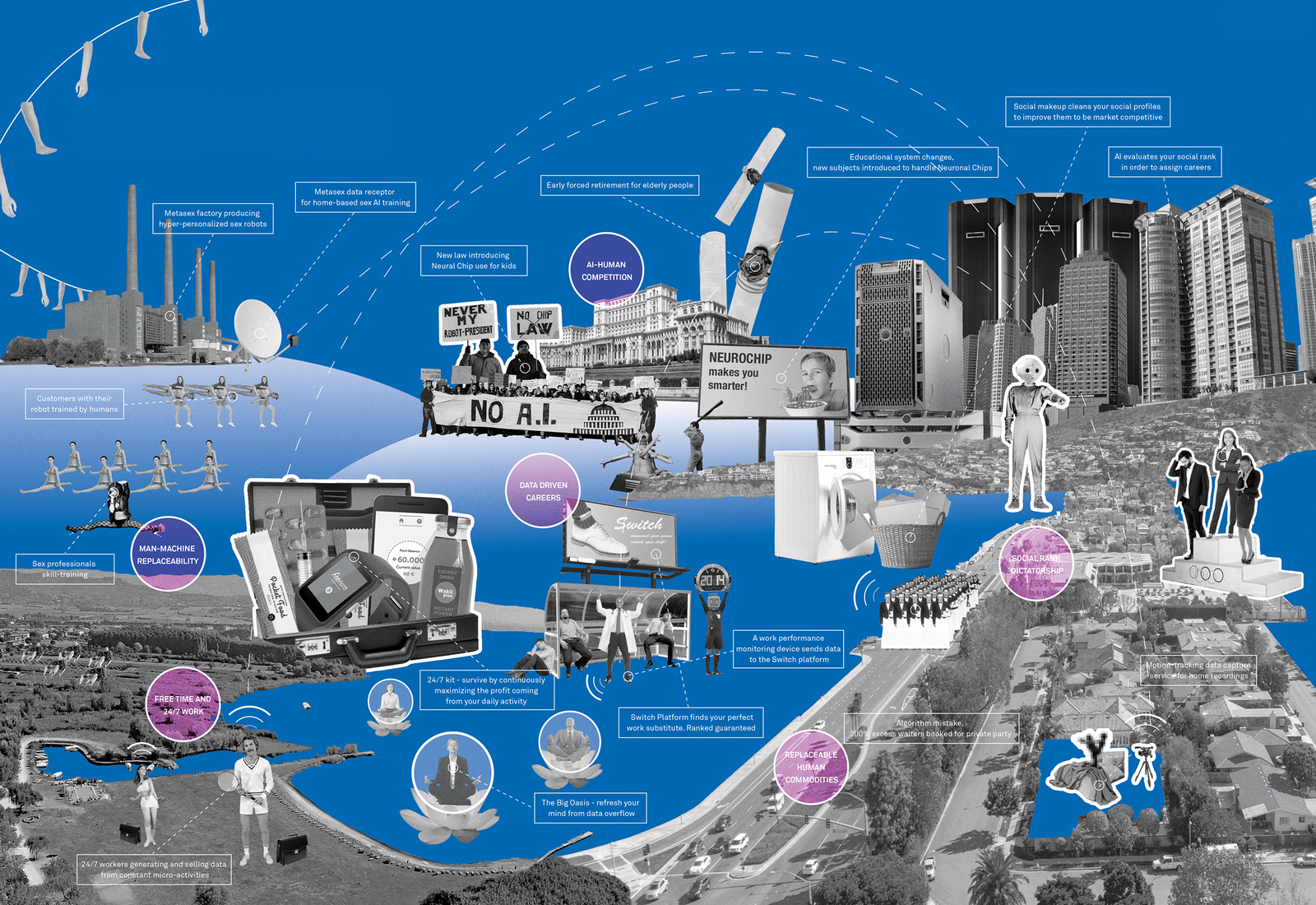

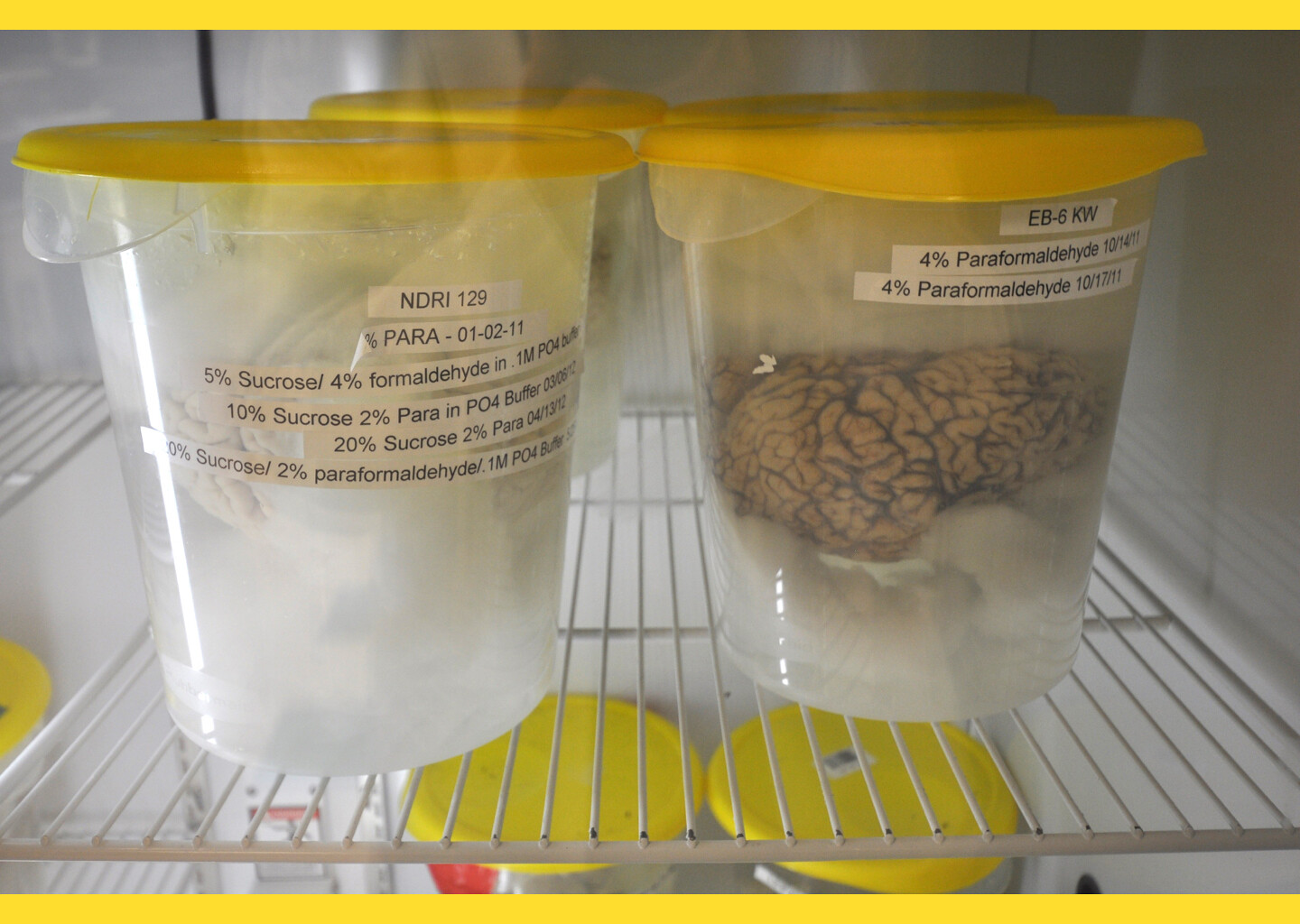

In the late 2010, food-and-mouth disease and avian influenza (AI) spread throughout the country. In most countries including Japan and the US, only the livestock in the infected farms were disposed of, but in Korea the government killed all animals within a three kilometer radius of the farms under investigation. The foot-and-mouth disease is a mild virus; it has a one percent mortality rate and can be cured in a mere ten days. Yet in spite of this, to secure the country’s status as an AI-free nation, over 3.5 million livestock animals including pigs, cows and goats were killed in eleven provinces and cities across South Korea, and four million uncontagious ducks and chickens were also killed. According to the regulation and guideline provided by the Animal and Quarantine Agency of South Korea, livestock should be disposed of by incineration after euthanasia, but most of the animals were buried alive in order to meet such rapid demands.14 Over 4,800 burial grounds were legally sealed by the government for three years. The hastily sutured sites are gradually returning to their nature in the form of the paddy fields and barns, yet in the process, in land where the smell of death still permeates the air, bones rise to the surface and blood seeps down and saturates the water, flowing into rice fields and rivers.

In 2014, the ban on forensic investigation was lifted on the burial grounds. These non-human subjects resurfaced as fractal images in germs, fungi and bones, shouting in silence to question the biopolitics of modernity. The buried, nameless animals are now returning to the ground as a sign of a revolt against the hygienic logic of modernization, a phenomenological proof of dehumanization and a fundamental question on the anthropocentric demarcation of life and death. The return of the primordial in Korea threatens the status reserved exclusively for humanity, which is the colonial superior vis-a-vis nature; furthermore, it now opens up the possibility that Otherization and objectification of humanity is negotiable. Along with the Sewol ferry incident, these animals raise new cultural discourses on Korean contemporaneity within the magnetic field of sovereignty and non-human subjectivities.

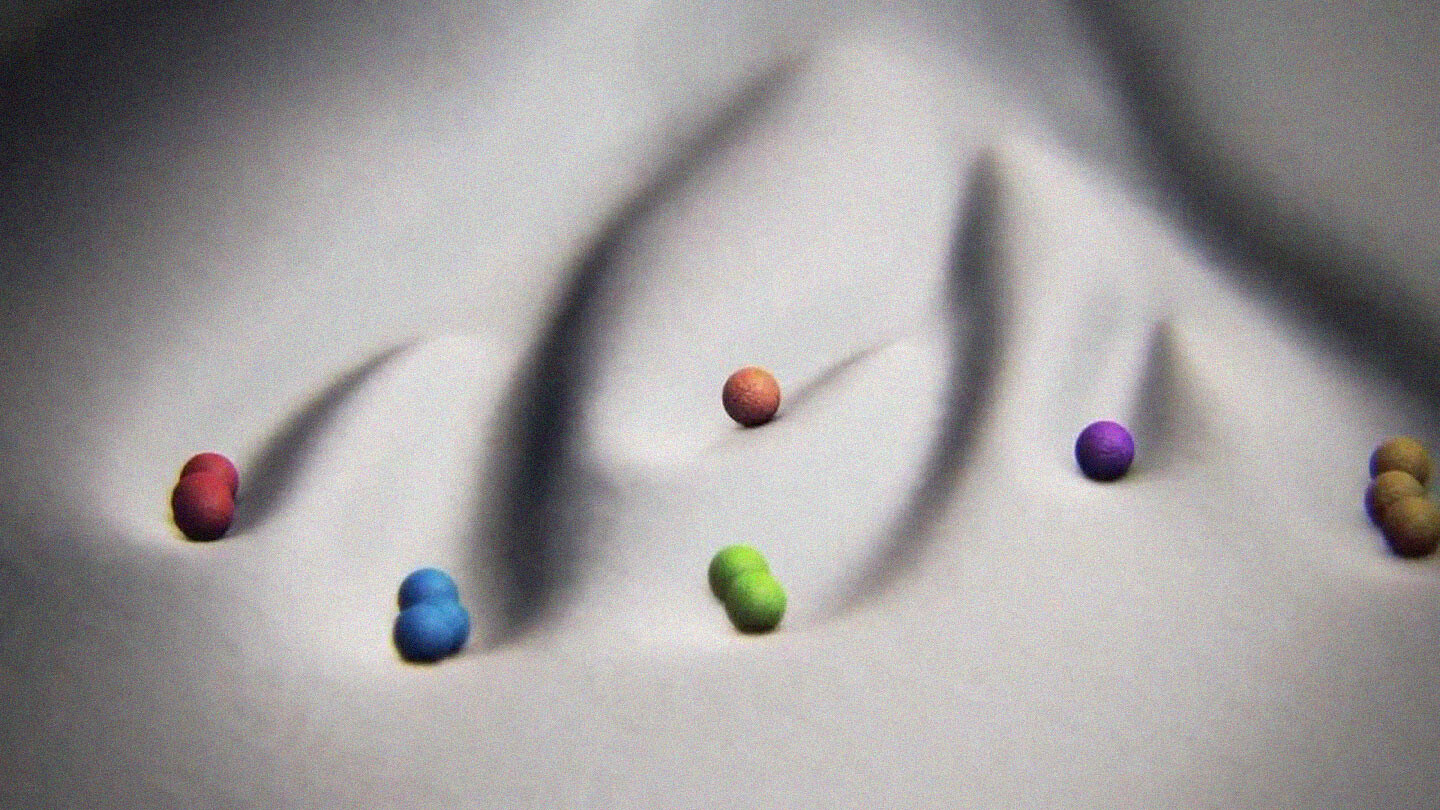

Photography by Seon Hee Moon of the site and number of dead animals. North Chungcheong Province, Jincheon, Pigs, 1765.

Coda

In discourses of modernity, the “repatriation” of animals and the primitive have been handled as if the subject was an appendage. Where is the limit of the ambiguous ethical questions on humanity? The logic of speciesism was first invented by Darwin. Imperial Japanese philosopher of science Tanabe Hajime of the Kyoto school gave it a slight twist to promote the ideology of ethnically homogeneous modern nation states and his logic of race (minzoku). What are the Lamarckian legacies implanted in our bodies that relentlessly Otherize races and non-humans in order to obtain a holistic comprehension of humanity? The non-human and animal, “neither human nor beast,” have always lived among us, and are trying to come back into presence.15 This essay must conclude with a discussion of how the return of the dispossessed, its dreadful prospects, and our screen memories of animality can be transformed and become curative memory.

I wish to be on guard against the humanist reflections of pseudo-postcolonial narcissism. Taking a position from the opposite side, animism/animality is a mirror reflection of humanity, defined as irrational and anti-scientific by modernity but then ultimately born again from it. I dream of humanity within animism in the form of the less familiar unconscious and new primal scenes. That is to say, I dream of animism as an alternative form of humanity that would manifest itself sometimes as a present-progressive form of sorcery and primitive religion and other times as an exuviated spirit of colonial modernity disjointed from time and space. I dream of a humanity that would put “the punctum of the uncanny” on all Otherized objects and forever remain as a healing memory.16

Maruboshi was a rail freight transportation and cargo unloading company that operated in every railroad station in colonial Korea. After liberation, it was classified as an enemy business and was nationalized. In 1962, it became Korea Transportation Ltd. (now Korea Express) and merged with Joseon Rice Warehousing.

Antonio Gramsci, Selections from the Prison Notebooks, (New York: International Publishers, 1971), 276.

Richard F. Calichman, What is Modernity? Writing of Takeuchi Yoshimi, (New York: Columbia University Press, 2005). For a discussion of universalism and particularism of the West and East in modern knowledge, see Naoki Sakai, “Dislocation of the West and the Status of the Humanities,” Traces 1: A Multilingual Journal of Cultural Theory and Translation, Specters of the West and Politics of Translation, (2001); 71-94.

“Ephemera Orientalis McLachlan (…) is a common burrowing mayfly which is found distributed throughout temperate East Asia including northeastern China, Mongolia, the Russian Far East, the Korean Peninsula, and the Japanese Islands (Hwang et al. 2008). The larvae occur abundantly in the lower reaches of streams, rivers, and lentic areas such as lakes and reservoirs, and are becoming more important in the biomonitoring of freshwater environments. The mass emergence and light attraction behavior of this species during the late spring and summer seasons, however, frequently causes serious nuisance to people residing in towns and cities near streams and rivers. This species is particularly abundant in the Han River that runs across Seoul and the frequency and intensity of its mass emergence has evidenced an increase in recent years.” Jeong Mi Hwang, Tae Joong Yoon, Sung Jin Lee and Yeon Jae Bae, “Life history and secondary production of Ephemera orientalis (Ephemeroptera: Ephemeridae) from the Han River in Seoul, Korea,” Aquatic Insects, Vol. 31, Supplement 1, (2009) 333–341, ➝.

The nutria (Myocastor coypus), also known as river rat, was first imported in Korea in 1987 from Bulgaria for meat. They were initially farmed in Yongam-ni, Seosan-gun, South Chuncheong Province. However, the nutria meat business did not quite take off in Korea, and thus nutria farmers began abandoning the business and releasing the giant rats into the wild. The rats have now become a serious threat to the environment and are being hunted and killed.

She describes the wax figure in the Musée Gravin as a “Wish Image as Ruin: Eternal Fleetingness,” that “No form of eternalizing is so startling as that of the ephemeral and the fashionable forms which the wax figure cabinets preserve for us. And whoever has once seen them must, like André Breton (Nadja, 1928), lose his heart to the female form in the Musée Gravin who adjusts her stocking garter in the corner of the loge.” Susan Buck-Morss, The Dialectics of Seeing: Walter Benjamin and the Arcades Project (Cambridge, Mass. and London: MIT Press, 1991), 369.

For more reference about the colonial anthropology and its tactics during the Imperial era, see Sakano Tohru, Teikoku Nihon to Junyuigakusha (Imperial Japan and Anthropologists) (Tokyo: Keiso Shobo Publishing, 2005) and Wartime Japanese Anthropology in Asia and the Pacific, eds. Akitoshi Shimizu and Jan van Bremen, (Osaka: National Museum of Ethnology: 2003).

Homi K. Bhabha, The Location of Culture (London: Routledge, 1994).

The term “ethnic abjection” was first used by Rey Chow in “The Secret of Ethnic Abjection.” Postcolonial theories have contributed to the global spread of the discourse of hybridity and cultural diversity as counter narratives to trans-nationalism and globalization. “Ethnic abjection” refers to the identity of heterogeneity that is being artfully concealed within this counter-discursive frame and the emotional structure of the ambiguity, rage, pain, and melancholy brought about by the politics of recognition. Rey Chow, “The Secret of Ethnic Abjection,” Traces 2: A Multilingual Journal of Cultural Theory and Translation, Specters of the West and Politics of Translation, (2001); 53-77.

During the Park Chung-hee dictatorship in 1960s-1970s, North Koreans were frequently represented in popular media as animals such as rats, pigs, wolves, and foxes, and became associated with the hatred and negative symbolism that these animals carry for their potential to spread infectous disease, such as typhus and epidemic hemorrhagic fever. In so doing, anti-communist narratives constituted an uncanny heterogeneous contemporaneity with the culture of (post-)colonial Japanese. Therefore, various class, gender and ethnic-based narratives suddenly become sutured under the rubric of modernization and national security.

The Sewol Ferry incident occurred on 16 April 2014 and killed more than 300 people, mostly high school students on the school trip going to Jeju Island. It is seen as a disaster that resulted from the combination of the government’s lack of effort, evasion of responsibility and mishandling of a very preventable disaster. The disaster created an outrage in South Korea and created a demand for special legal investigation of the disaster to reveal and bring to justice parties who were responsible for the sequence of events. This demand, however, was met with disappointing response from the government, being misrepresented and mis-portrayed as an effort to shift blame to the victim’s families and suppress the protests.

This term is borrowed from Andreas Huyssen, with which he tries to explain the academic discussion and exhaustion of topics of memory. Andreas Huyssen, Present Pasts: Urban Palimpsests and the politics of memory, (Stanford: Stanford University Press: 2003), 3.

These questions are proposed by Judith Butler in drawing on Agamben’s notion of bare life to the post-9/11 Iraq war America. Judith Butler, Precarious Life: The Powers of Mourning and Violence (London: Verso, 2006), 20.

Among the places where the animals were buried alive, there were many sites that did not obey the instructions to install basic facilities such as drainage with perforated drainpipe. See ➝.

For Agamben, the wolf symbolizes a metonym of the return of the primitive in the collective unconscious, as what he describes “a monstrous hybrid of human and animal.” He said “what had to remain in the collective unconscious as a monstrous hybrid of human and animal, divided between the forest and the city – the werewolf – is, therefore, in its origin the figure of the man who has been banned from the city. (…) The life of the bandit, like that of the sacred man, is not a piece of animal nature without any relation to law and the city. It is, rather, a threshold of indistinction and of passafe between animal and man, physis and nomos, exclusion and inclusion: the life of the bandit is the life of the loup garou, the werewolf, who is precisely neither man nor beast, and who dwells paradoxically within both while belonging to neither.” Giorgio Agamben, Homo Sacer: Sovereign Power and Bare Life, trans. Daniel Heller Roazen, (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1998), 105.

“The punctum of the uncanny” is a phrase Hal Foster uses in reference to Roland Barthes’s concept of “punctum.” Barthes speaks of “the tactile trace, the marks that photography leaves on our body.” Foster is referring to the uncanny feeling one gets from objects that seem to actually exist. This is related to the Freudian “return of the repressed,” or the unconscious desire to return to the state of not knowing the distinction between life and death, between organism and inorganic substance. Hal Foster, Compulsive Beauty, (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1993).

Superhumanity is a project by e-flux Architecture at the 3rd Istanbul Design Biennial, produced in cooperation with the Istanbul Design Biennial, the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea, the Govett-Brewster Art Gallery, New Zealand, and the Ernst Schering Foundation.

Category

Superhumanity, a project by e-flux Architecture at the 3rd Istanbul Design Biennial, is produced in cooperation with the Istanbul Design Biennial, the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea, the Govett-Brewster Art Gallery, New Zealand, and the Ernst Schering Foundation.