I’ve long thought that conventional understandings of geography were a little too “horizontal”. That geographical concepts such as production, uneven development, territory, scale, geopolitics and the like tended to be theorized on an assumed horizontal plane of human existence makes sense, because the vast majority of human activity does more-or-less conform to the relatively narrow vertical band on the earth’s surface that can support human life. But human infrastructures and activities also inhabit a vertical axis, from deep sea mining and undersea cables to outer, and even arguably interstellar, space. As others have observed, different topologies of development, politics, urbanism, and the production of space emerge when we begin to consider the vertical dimensions of human world-making.1

What follows are some sketches of case-studies from my own work that have been personally helpful in considering what a theory of vertical geography might encompass. There is nothing comprehensive here, nor anything actually theorized at all. These are simply some examples of things I think about.

-20,000ft (Undersea Cables)

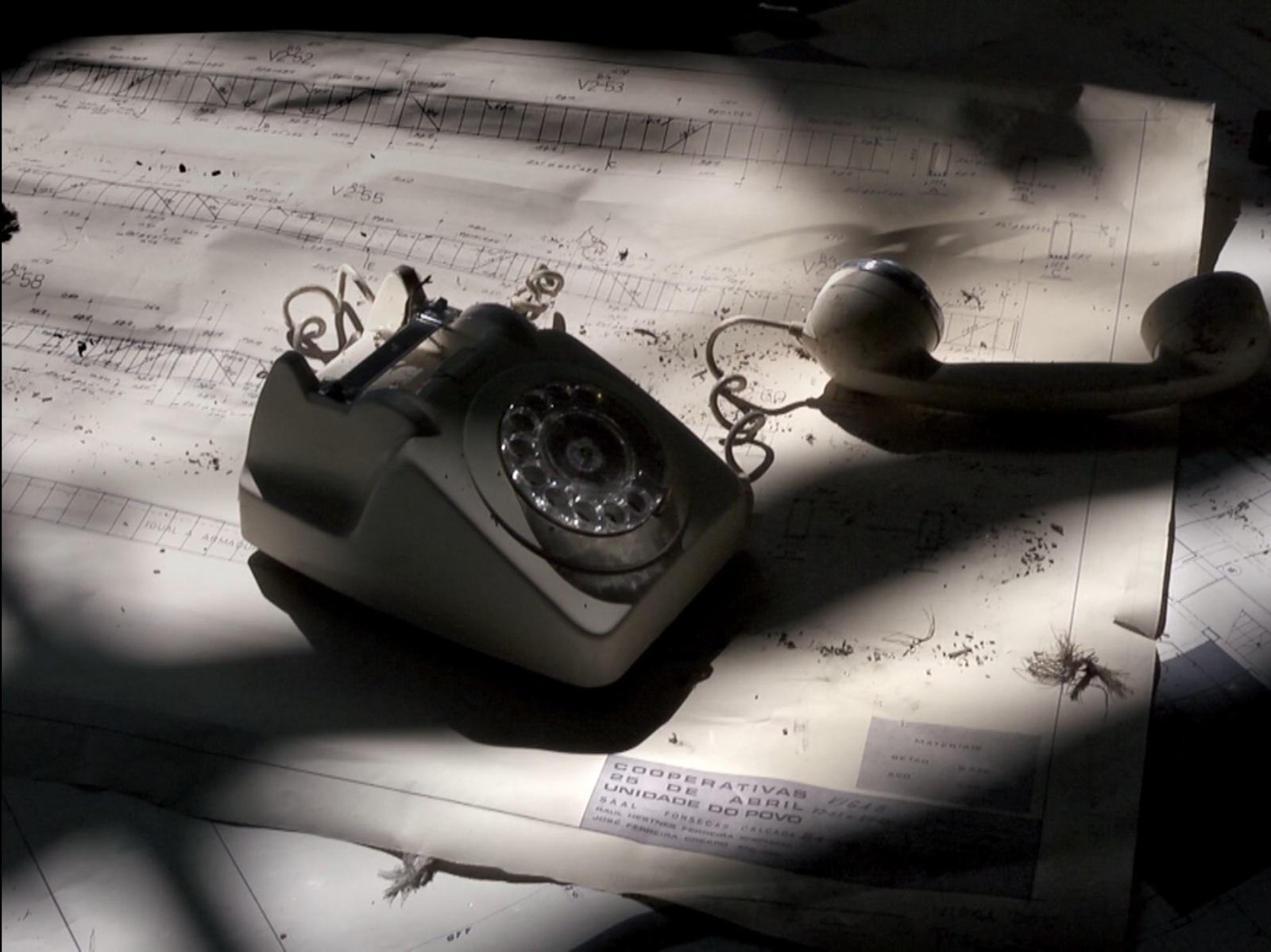

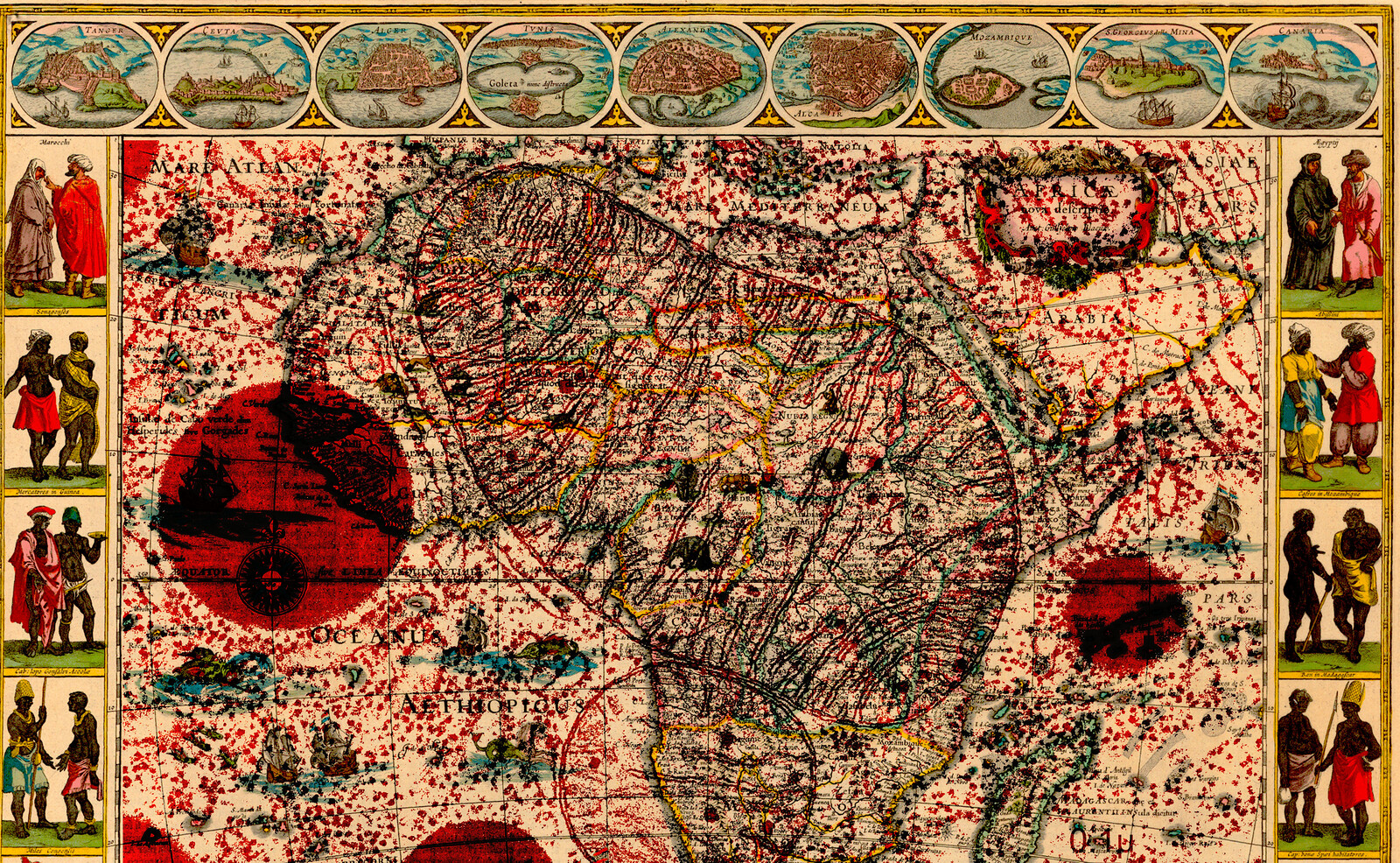

More than 99% of the world’s data travels through fiberoptic cables draped across the ocean floor. Undersea cable encircle the globe at depths of 20,000ft (6,000m), connecting continents and providing the backbone of the world’s telecommunications infrastructure.

After an aborted attempt in 1857, the first undersea cable connecting North America to the UK was laid in 1858 when the warships Niagra and Agamemnon met in the middle of the Atlantic to splice the two ends of the telegraph cable they had lain from their respective ports. The first transcontinental conversation (which took a day to conduct) was the following:

Repeat, please.

Please send slower for the present.

How?

How do you receive?

Send slower.

Please send slower.

How do you receive?

Please say if you can read this.

Can you read this?

Yes.

How are signals?

Do you receive?

Pease send something. Please send V’s and B’s.

How are signals?

Within a month, the cable was dead. Other attempts between 1857 and 1866 either failed outright or after short amounts of time. The first reliable cable came online in 1866.2 As of 2016, there are more than 300 active undersea cables.

The undersea world of cables and communications is studied and acted upon by an American intelligence agency called the National Underwater Reconnaissance Office (NURO), jointly staffed by the CIA and the Navy.3 A sister agency to the National Reconnaissance Office (charged with the operations of reconnaissance satellites), the NURO conducts undersea surveying, search operations, oceanographic research, and the installation of undersea infrastructure, including taps on undersea cables. Since its inception in 1969, the NURO has deployed a handful of specialized ships and submarines to conduct its operations, including the USS Parche, the Hughes Glomar Explorer, the USS Halibut, the NR-1, and the more recent USS Jimmy Carter. The National Underwater Reconnaissance Office is a so-called “black” agency, meaning its existence is classified.

The deep-sea geographies of internet cables and telecommunication are, quite literally, a submerged infrastructure that exists far below the altitudes that can support human bodies. On a vertical axis, the depth of undersea communications and reconnaissance activities is only superseded by specialized oil-drilling activities; the ill-fated Deepwater Horizon platform in the Gulf of Mexico drilled the deepest oil well in history at a vertical depth of 35,055ft (10,685m).

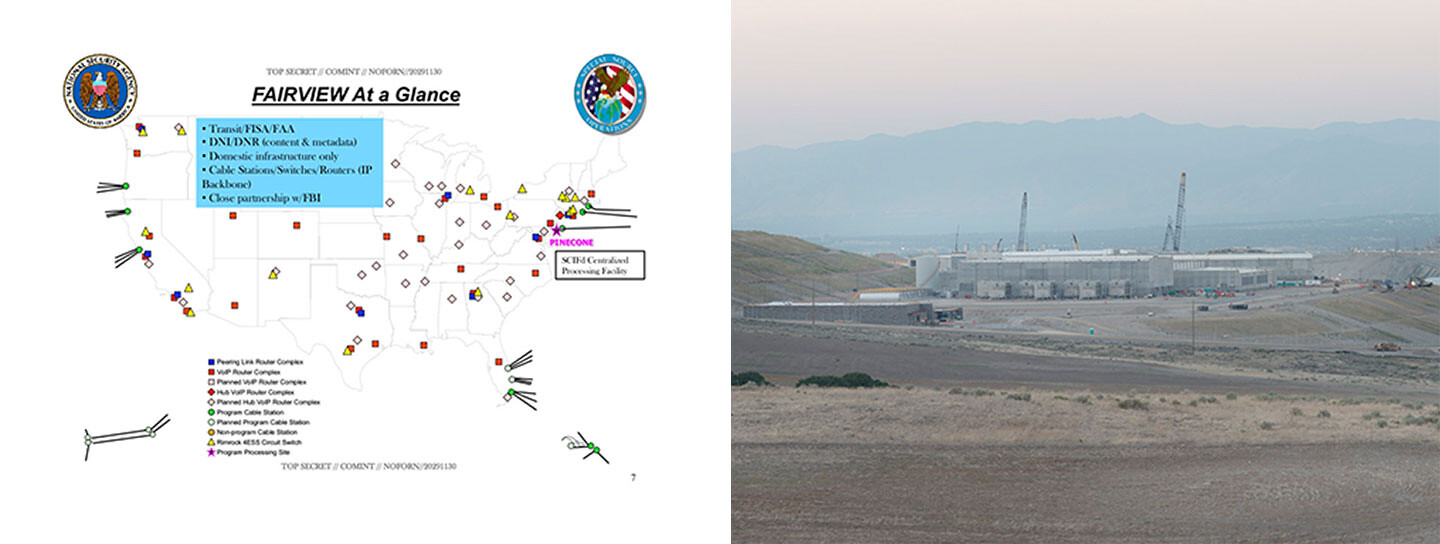

Left: Internal NSA Document, “FAIRVIEW”; Right: Author’s field note: NSA Utah Data Center.

0 (Backbone)

Cable landing points are the places where undersea cables come onshore, usually connecting to a building called a cable landing station. The cable landing station is typically a windowless building that supplies power to an undersea cable’s amplifiers and repeaters (a typical undersea cable has between three and four thousand volts applied to it). In many cases, the cable landing station also connects the undersea cable to terrestrial “backhaul” cables, which lead to the common internet backbone, with switches, core routers and other equipment, effectively connecting the undersea cable to the terrestrial internet infrastructure.

Cable landing stations serve as natural “choke points” of the internet, and are therefore of great interest to intelligence agencies like the NSA. Numerous internal NSA documents describe the importance of cable landing stations as surreptitious data-collection sites, often in collaboration with local telecommunications companies, including AT&T (“FAIRVIEW” in internal NSA documents), Verizon (“STORMBREW”), British Telecom (“REMEDY”), Vodafone Cable (“GERONTIC”), etc.

2,500ft (Persistent Surveillance)

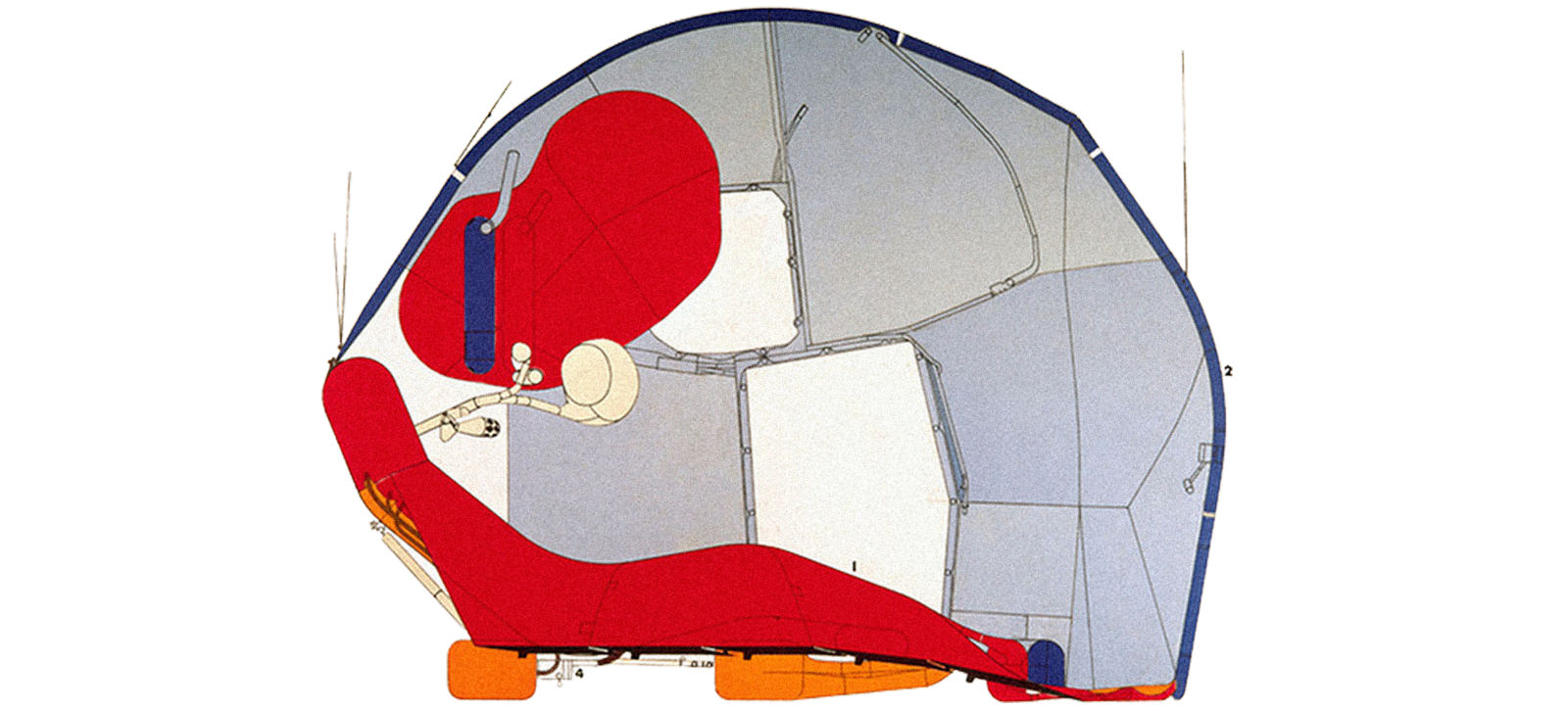

Modern aerostats began to see widespread use in the 1980s when the US Customs Service installed the Tethered Aerostat Radar System (TARS) at High Rock, Grand Bahamas and Fort Huachuca, Arizona as part of the Reagan-Era “War on Drugs.”4 These airships were designed to provide radar-surveillance of border regions, and have been subsequently deployed throughout the Caribbean and Southwest at: Cudjoe Key, Florida; Deming, New Mexico; Eagle Pass, Texas; Fort Huachuca, Arizona; Lajas, Puerto Rico; Marfa, Texas; Rio Grande City, Texas; and Yuma, Arizona.

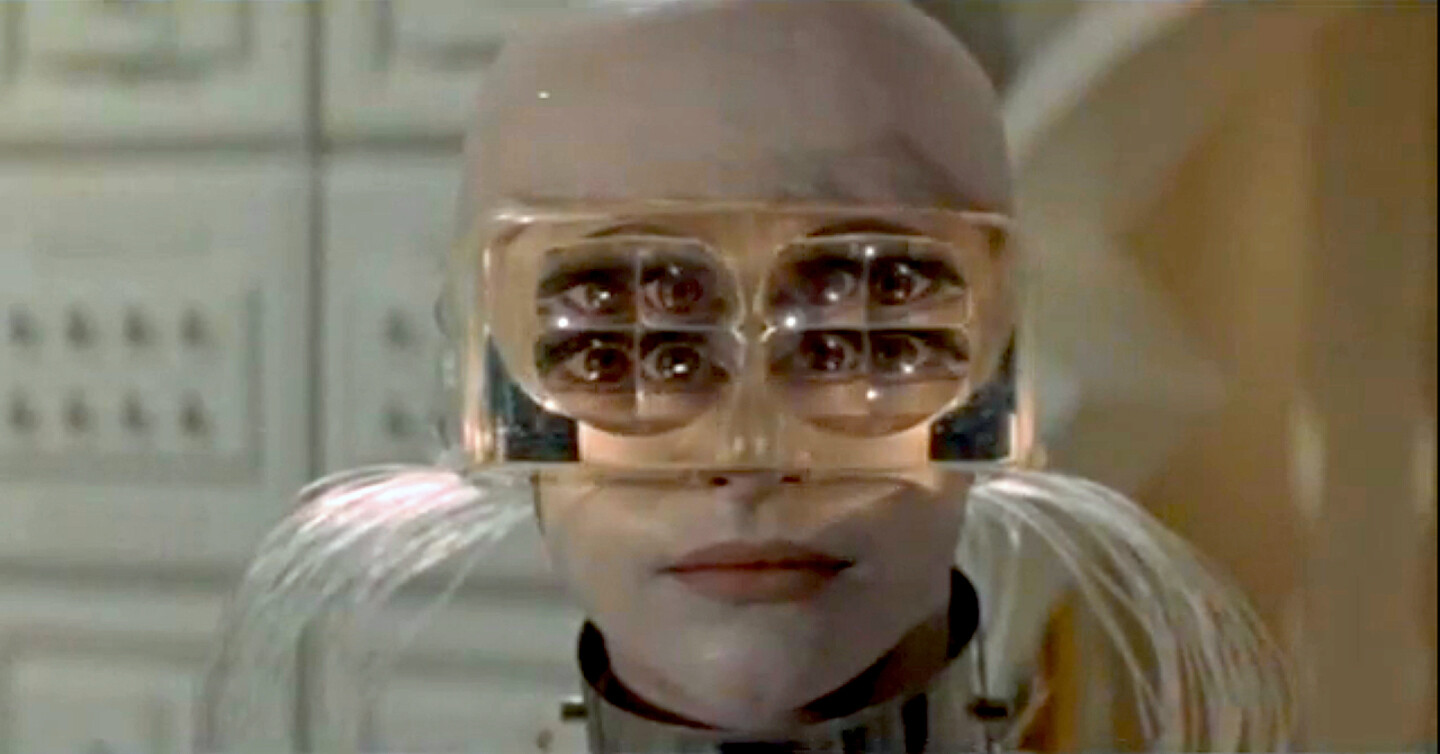

In the aftermath of the US invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq, the US Army contracted Lockheed Martin to develop aerostats that could be used to conduct persistent surveillance over occupied cities. The first Army aerostat was deployed in 2004. In the ensuing years, the Army has ordered and installed dozens of other aerostats over urban centers and war zones. Military aerostats utilize surveillance and sensor payloads such as Gorgon Stare, Kestral, and ARGUS-IS (Autonomous Real-Time Ground Ubiquitous Surveillance Imaging System, which uses 368 cell phone cameras to provide a 1.8 gigapixel video imaging system). ARGUS can continuously monitor a thirty-six square mile area and uses automated tracking software to algorithmically track vehicles, pedestrians, and other objects and to conduct automated “pattern-of-life” analyses. Other sensor packages are designed to track cell phone and geo-location metadata, conduct multispectral analysis, synthetic aperture radar imaging, and more.

Inspired by the military’s use of persistent surveillance systems over war zones, companies in the US have developed variations intended for domestic law enforcement. The most widely known of these, Persistent Surveillance Systems of Dayton, Ohio, uses modified lightweight aircraft to provide law enforcement with continuous 0.5m resolution video over a sixty-four square kilometer area. An export-authorized variation on the military’s Kestral system, developed by a company named Logos, is scheduled to be deployed on four aerostats over the Rio de Janiero Olympics. “We create a Google Earth view of the city and update it every second,” John Marion, President of Logos, told Popular Mechanics, “And we store everything, so we can go through it like TiVo.”5

25,000ft (Predators, Reapers, Sentinels)

260,000ft (Numbers)

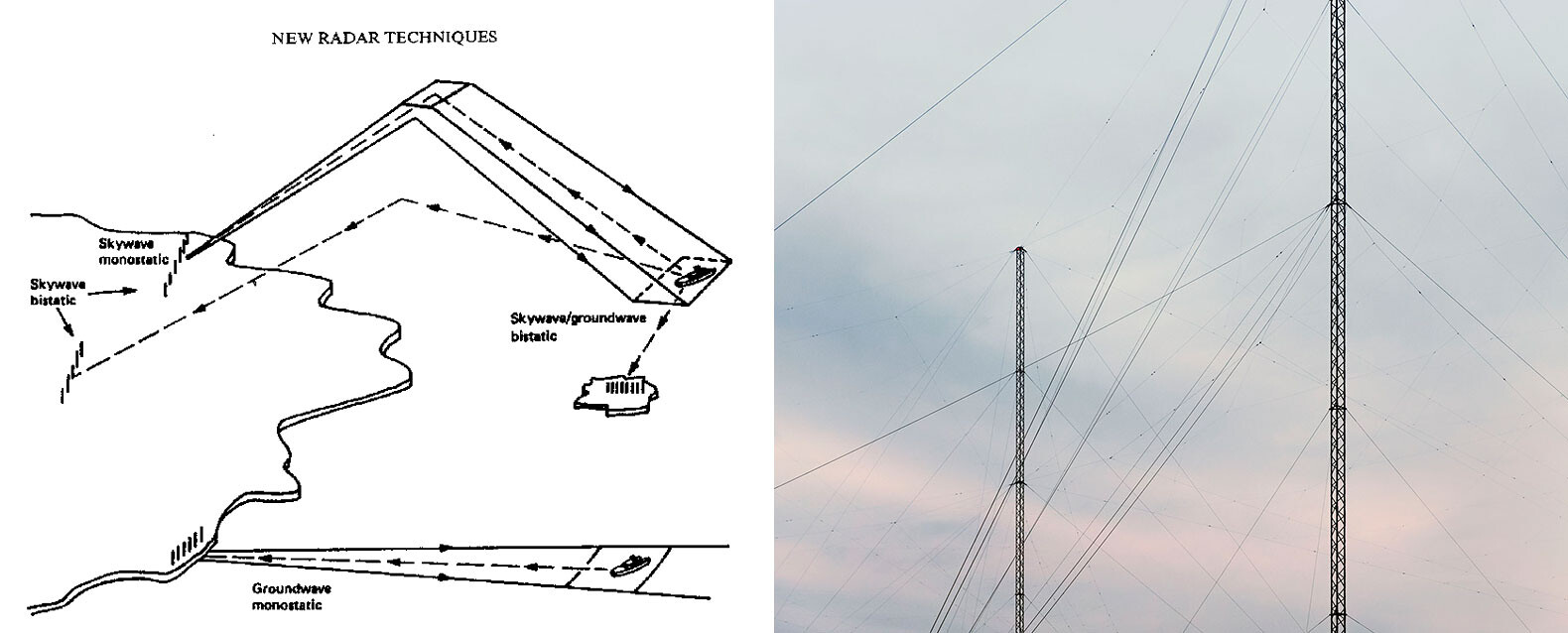

In the 1920s, amateur shortwave radio operators discovered something unusual about radio transmissions between 1.3–30Mhz: when radio transmissions at these frequencies encountered ionized air in the upper atmosphere, they were “backscattered”, “skipping” back to earth. This meant that shortwave signals could be used for long distance communication and other applications beyond the “line of sight” limitations of most radio transmissions.

Throughout the Cold War and into the present, amateur radio enthusiasts and state entities have taken advantage of skipping in a number of ways, like stations broadcasting propaganda and news or militaries creating “over the horizon” radar systems and developing detection capabilities in otherwise inaccessible regions. Transmitting shortwave is inexpensive, difficult to censor and ownership of shortwave radio outside the western world is common. Moreover, much machine-to-machine communication happens over shortwave, especially in applications for synchronizing time across global infrastructures, oceanic air traffic control, and weather reporting.

The most unusual signals skipping between the earth surface and ionosphere are arguably the “number stations”, which typically consist of a computer generated voice reading seemingly random sequences of numbers, usually preceded by a signature piece of music or other unique sound to identify itself. Numbers stations are used by intelligence agencies to communicate with agents in the field; the signals’ intended recipient is able to decode the signal using a “one-time pad”, an encryption technique that is mathematically impossible to decrypt. While number stations were far more pervasive during the Cold War, there are a few still in use. Although finding the source of shortwave broadcasts can be exceptionally difficult, radio enthusiasts have been able to trace some numbers stations to various intelligence installations.

160–2,000km (Low Earth Orbit)

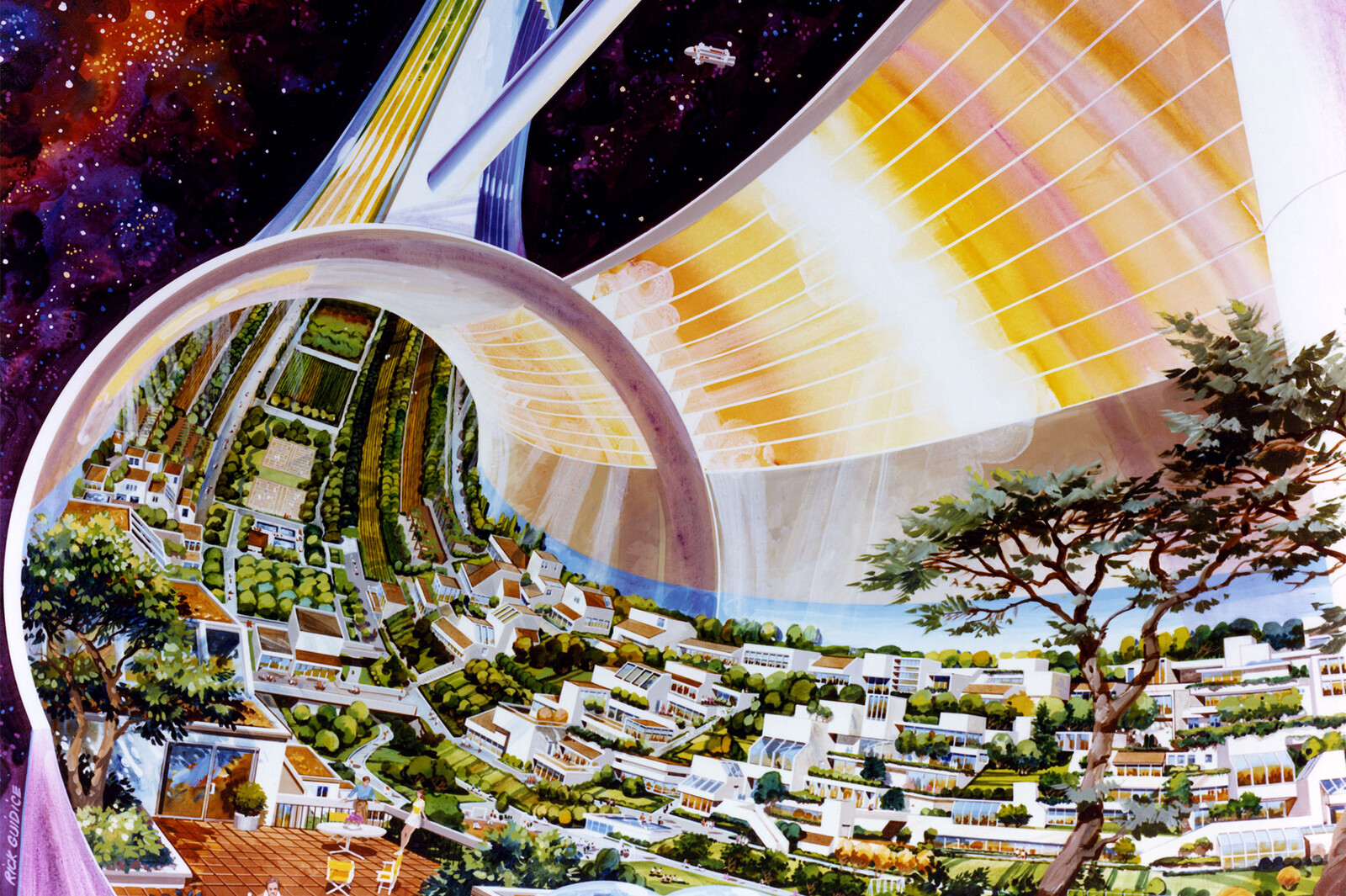

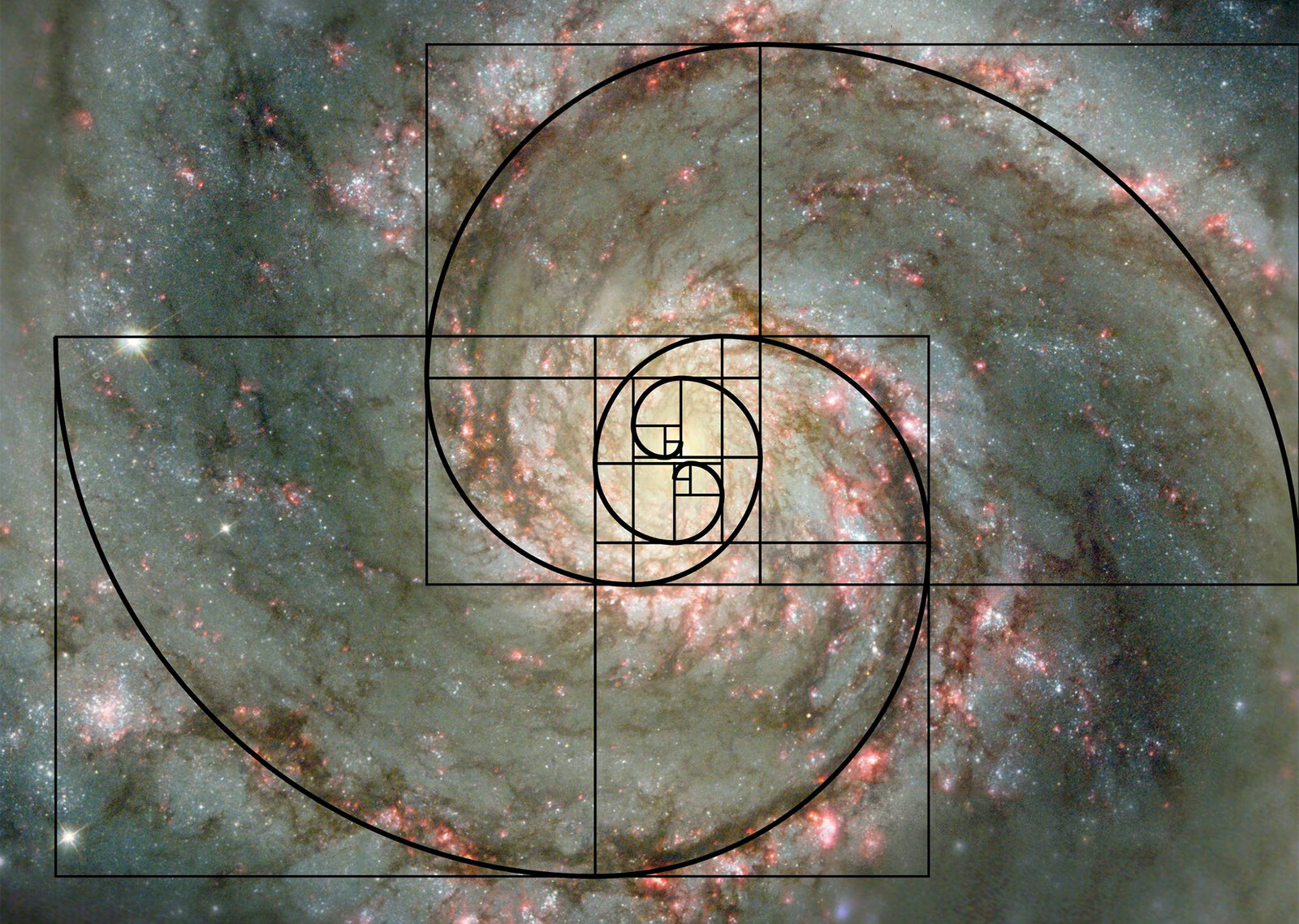

One of the most important things to understand about space, explains military space theorist Jim Oberg, is that “space is unearthly” and that “much ordinary ‘common sense’ doesn’t apply. One has to be cautious about making analogies with everyday life.”6 Oberg’s point is that objects in orbital space inhabit very different topologies than more familiar infrastructures on the planet’s surface. Orbital space isn’t even closely analogous to the strategic notion of “high ground” used in terrestrial military theory, but neither is orbital space smooth and undifferentiated, an unmodulated expanse of nothingness. Orbital space is rather a topology characterized by the gravitational interactions of the sun, earth, moon, and outer planets; by irregularities in the earth’s surface that translate into gravitational peaks and troughs in orbital space; by magnetic fields, solar radiation pressure, and by stray atmospheric molecules that travel upwards. What’s more, the topology of orbital space is strongly influenced by geopolitical and economic policies and conventions of spacefaring nations on the earth below.

Low Earth Orbit (LEO) is generally defined as the orbital region between about 160–2,000km from earth (objects cannot remain in orbit under 160km), and is where the vast majority of earth’s satellites are based. LEO is primarily used for remote sensing and imaging satellites, scientific monitoring, and communications infrastructures such as the Iridium system, the most popular satellite phone network. Low Earth Orbits are also the domain of optical and radar-imaging reconnaissance satellites, which take advantage of their closeness to earth to conduct high-resolution photography over vast swaths of land in a short periods of time.

The fact that low earth orbit exists at all is the result of a geopolitical quirk that became a de facto convention. Before the Soviet Union launched Sputnik, no one knew whether a satellite in orbit could be said to violate the territorial integrity of the nations that it overflew. As historian Everett Dolman points out, the Eisenhower administration was secretly elated that the Soviet Union first established the precedent that a satellite in orbit did not violate the sovereignty of the countries that it overflew.7 Some historians have gone so far as to suggest that the Eisenhower administration deliberately allowed the Soviets to put to first object in orbital space, confident that American spy satellites in development would be able to use the Soviet precedent to overfly and conduct reconnaissance of the Russian interior without resorting to the increasingly dangerous U-2 spy plane program.

Still to this day there is no internationally agreed upon vertical limit of a nation’s territory. The highest airships and balloons can operate up to an altitude of about 37km, while the lowest satellites can only operate at approximately 160km. The fact of this practical “grey zone” in which no vehicles typically operate has meant that it’s been unnecessary to define an agreed-upon international convention on the limits of vertical sovereignty.

Left to right: Author’s field notes: Geostationary Orbit; Author’s notes on work: Powler; MiTEx Patch; Geostationary orbit demonstration

36,000km (Geostationary Orbit)

The “space” in “earth-orbit-space” that has most in common with terrestrial territory is the geostationary-orbit (GEO), a thin gravitational ring only a few kilometers thick and wide, 36,000km directly above the equator. This space is important to the world’s militaries, intelligence agencies, and corporations because objects placed in GEO orbit the earth at the exact same rate that the earth itself rotates. An object in geostationary orbit effectively “hovers” over a particular place on the earth’s surface, making it an ideal location for communications satellites. Because the ring of space where the geostationary orbit “works” is so thin, and because prime geostationary “slots” are finite, the International Telecommunications Union (ITU) regulates the allocation of space within the geostationary belt.

The geostationary belt of commercial and military communications satellites, data relay satellites, and television and broadcast satellites—all of which are, in fact, small variations on a basic “communications satellite” design—are a core part of global military and commercial telecommunications systems. Unsurprisingly, the geostationary belt is also home to scads of signals intelligence (SIGINT) satellites designed to vacuum up communications of all sorts emanating from the planet below.

At a distance of 36,000km above earth, geostationary orbit is far more distant than the satellites in low-earth-orbit (160–2000km). This makes ground-based monitoring of the geostationary belt exceptionally difficult. As the American military began developing technologies and techniques of counter-surveillance and covert action, an increasingly significant geopolitical infrastructure is being placed in GEO. Beginning with a classified payload called “PROWLER” in the early 1990s and continuing more recently with spacecraft like “MiTEx” (Micro-satellite Technology Experiment), the US military has sought to build small, stealthy spacecraft that can wander undetected through the geostationary orbit. The ultimate goal of such satellites appears to be the the capability to turn on and off other countries’ military and commercial communications infrastructures, and to do it in such a way that the institution being targeted wouldn’t be able to attribute the attach to any specific agent or even differentiate between an attack and a mechanical failure.

In the longer term, geostationary spacecraft are not only part of the world’s communications backbone, but will invariable be some of the humans’ longest-lasting artifacts. Because the belt is so far from earth, GEO spacecraft don’t experience orbital decay (which is caused by small quantities of atmospheric molecules that made it into space and induce drag on lower orbiting spacecraft). In an environment absent of erosion, volcanism, rain, winds and other geomorphic processes, the spacecraft in geostationary orbit could potentially remain there for billions of years into the future, long after humans have gone extinct or evolved into other life forms as alien to mankind as lobsters.

60ly (Galaxy)

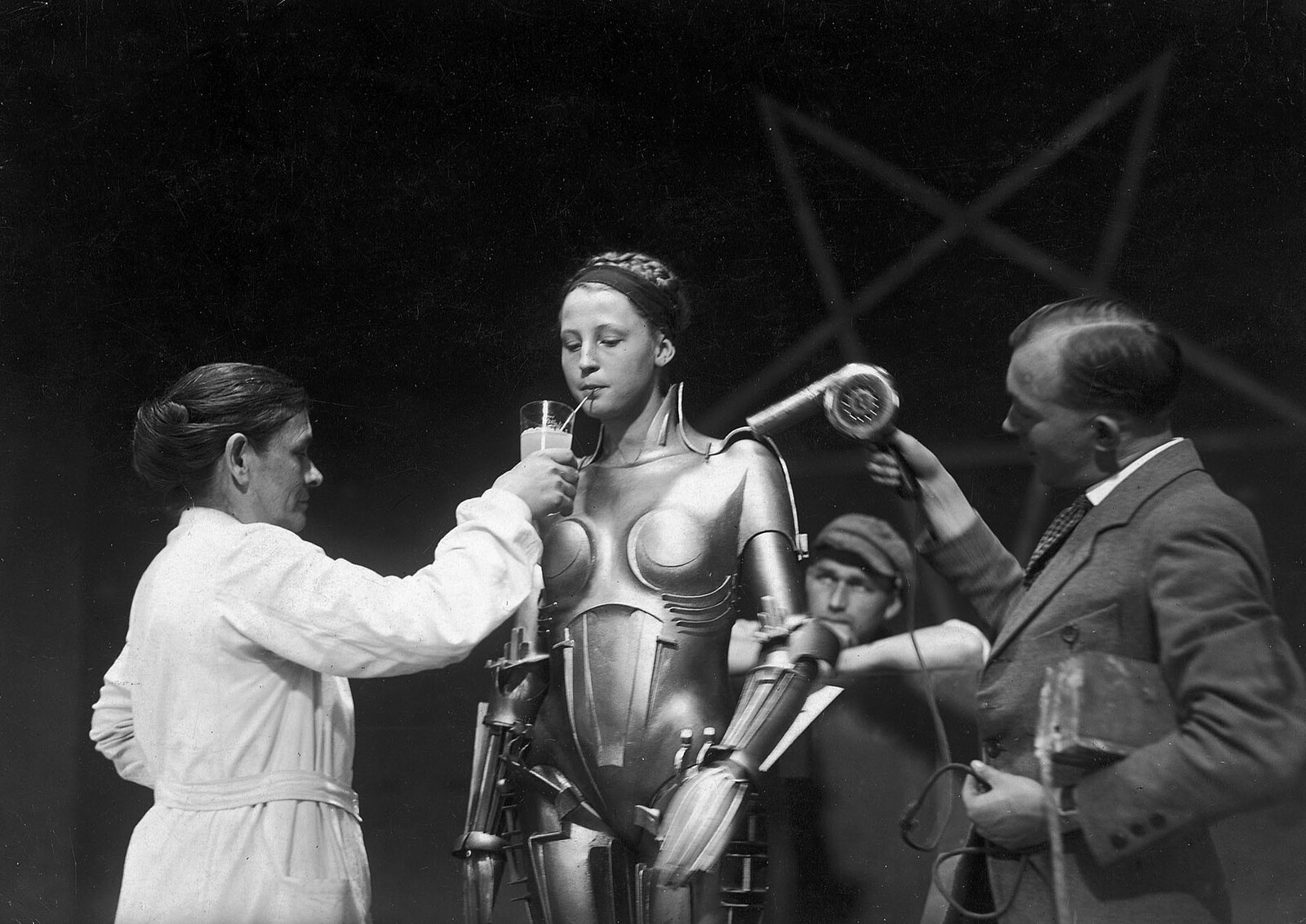

Researchers involved in the Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence (SETI) understand that their discipline has a paradox at its core, which is that no one knows what an extraterrestrial civilization (ET) is supposed to look like. Thus, scientists periodically ask what human civilization might look like to a civilization in the vicinity of a distant star. It turns out that the earth looks like a kind of cosmic lighthouse, oscillating with a distinct spectral signature of radio peaks and valleys over a twenty-four hour period.

In 1979, astronomer W. T. “Woody” Sullivan worked with two undergraduates at the University of Washington to publish a now-classic paper entitled “Eavesdropping: The Radio Signature of Earth”.8 Sullivan et al. found that the brightest continuous signals emanating from earth came from military radar systems designed to detect ballistic missiles and track satellites in earth orbit, followed by carrier waves used in conventional television broadcasting. The researchers concluded that since 1957, when significant military radar systems began going online, “the earth has indeed become a very bright planet, in fact easily outshining the sun in certain narrow frequency ranges.”

In “Eavesdropping”, the astronomers pointed out that earth’s galactic footprint now extends to neighboring planets up to about sixty light years away (the distance that military radio waves have travelled since they started going online in the late 1950s). What’s more, they pointed out, an alien civilization examining earth’s radio signature could deduce “far more … about our culture than one would at first think.” “The very fact that we allow all of this power to escape might be taken as a sign of our prodigal nature,” the authors surmised, “or even of our lack of an ethic concerning environmental pollution in our galaxy.” Moreover, the repeating peaks and valleys of our planet’s radio signature might strongly imply the uneven economic development that characterizes human societies, and the political, territorial, and cultural divisions that characterize human civilizations.

From its inception in the 1960s to its closure in 2013, earth’s most powerful radio source was a 216.983MHz signal emanating 768kW from Lake Kickapoo, Texas. Colloquially known as “the Fence” or the “Space Fence”, the Lake Kickapoo transmitter was used to track satellites overflying the continental United States as part of the military’s space surveillance network. Although the Fence was shut down in 2013, it is being replaced with a new transmitter based at Kwajalein Atoll scheduled to go online in 2019.

Arthur C. Clarke, How the World was One (New York: Bantam, 1992).

Jeffrey Richelson, The U.S. Intelligence Community – Seventh Edition (Boulder: Westview Press, 2016); Shelly Sontag and Christopher Drew with Annette Lawrence Drew, Blind Man’s Bluff: The Untold Story of American Submarine Espionage (New York: Public Affairs, 1998).

See →.

See →.

Jim Oberg, Space Power Theory (US Air Force Academy, 1999).

Everett Dolman, Astropolitik: Classical Geopolitics in the Space Age (Routledge, 2001).

See →.

Superhumanity is a project by e-flux Architecture at the 3rd Istanbul Design Biennial, produced in cooperation with the Istanbul Design Biennial, the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea, the Govett-Brewster Art Gallery, New Zealand, and the Ernst Schering Foundation.

Category

Subject

Superhumanity, a project by e-flux Architecture at the 3rd Istanbul Design Biennial, is produced in cooperation with the Istanbul Design Biennial, the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea, the Govett-Brewster Art Gallery, New Zealand, and the Ernst Schering Foundation.