I

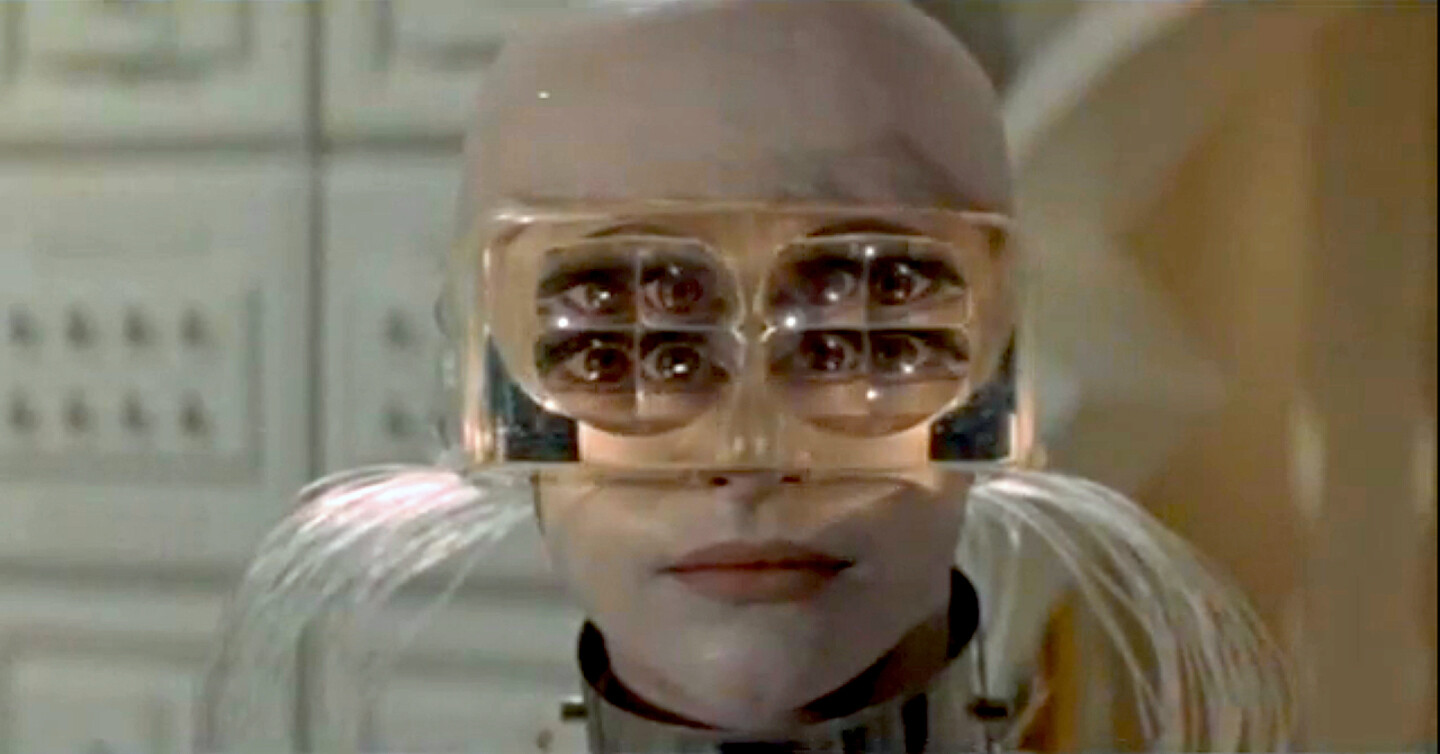

You burn me

—Sappho, addressing passion

A song from my childhood, by Fairuz, Lebanon’s most famous singer, goes like this:

I wish

You and I were in a house

A house the furthest house

Erased behind the frontiers of darkness and wind

And snow falling, wounding the surface of all things,

Making you lose your way, so that you would never leave,

And you would remain,

Next to me you would remain,

While a thousand season of jasmine would blossom, and wither

And you would remain,

Next to me you would remain,

Next to me you would remain,

And not one drop of oil would be left in the lantern

I wish

I wish

The song is considered romantic, like most of her songs (except the patriotic ones); the musical arrangements are vanilla-sweet, and the tonality of her voice is pure, with a touch of melancholy. These are all the ingredients needed to make a cheesy pop song about love, which the YouTube videos uploaded by fans have internalized, adding images of isolated cottages, flowers and hearts to the formula.

But is this song about love, really? One could argue that it isn’t, that the lyrics—which were actually written by a man—are more about possessing the Other rather than loving him, which leaves no place for love or desire to unfold, to blossom. This is perhaps true; the lyrics’ juvenile character, their immaturity, their remoteness from how love is experienced in today’s world, make them very unconvincing.

But in spite of all that, there is something very strange about these lyrics: they are knit together to create a universe of total darkness, “behind the frontiers.” The singer wishes to redesign the entire world in order to keep the man she loves next to her, which she does not by inventing a new world but simply by rearranging the elements that make up this one. In this universe there are no paths, because they are covered by the violent snow falling on the world, making it impossible for the man to leave the house even if he so wishes. This situation presupposes that the woman is already contained in the house and it is the man who arrives, after which the elements of Nature, redesigned by the woman, keep him from leaving. In this universe, there is no time: the moment of intimacy lasts for a thousand years, while flowers come into being and collapse into oblivion. In this universe there is no light; it is a universe of total darkness, where the absence of light is necessary to abolish the act of seeing, further locking the man in a universe with no points of reference that would help him orient himself.

Tony Chakar, “An Endless Quick Nightmare,” 2011

II

The earth was formless and void, and darkness was over the surface of the deep, and the Spirit of God was moving over the surface of the waters.

Then God said, “Let there be light”; and there was light.

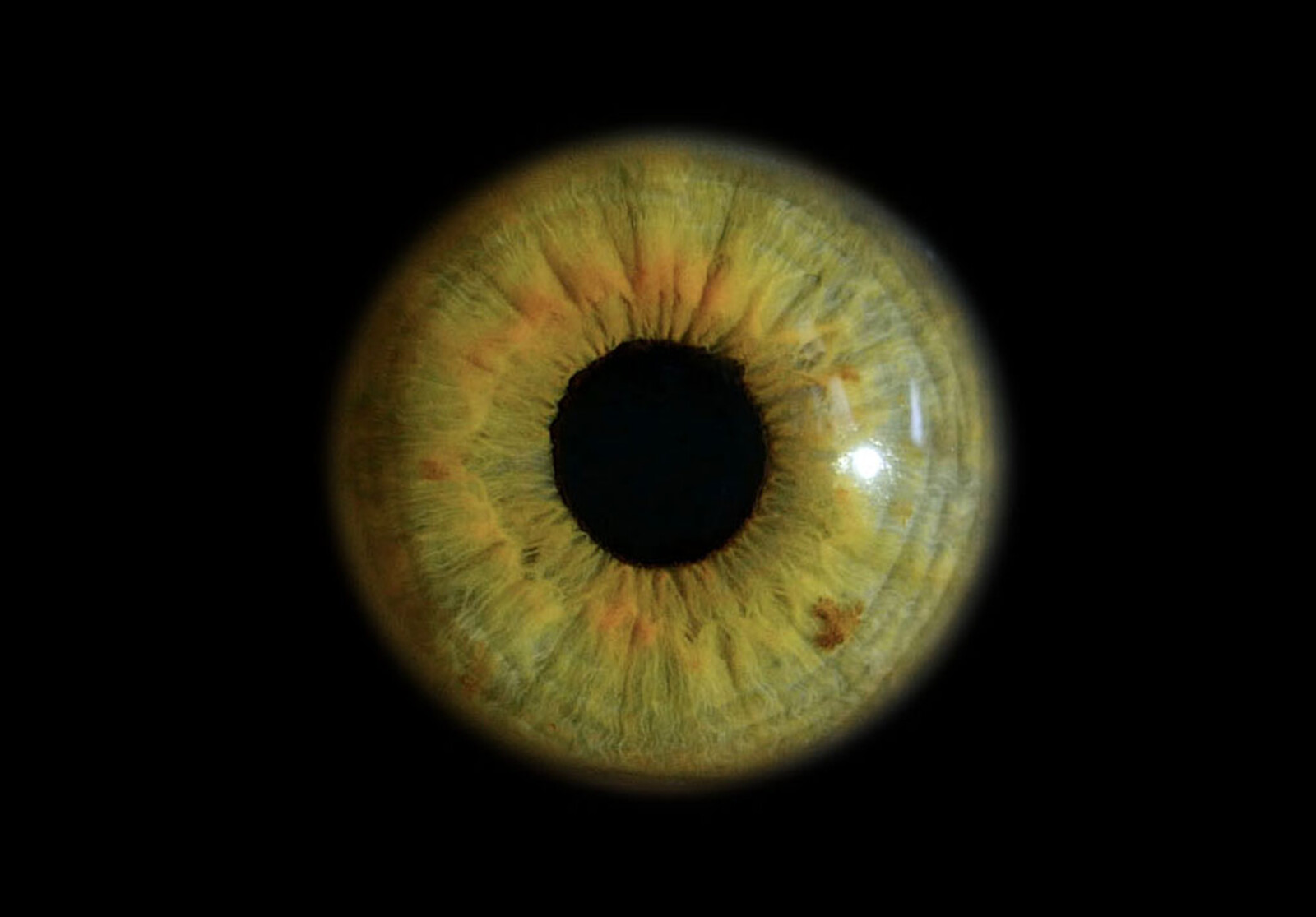

God saw that the light was good; and God separated the light from the darkness.

— Genesis 1:24

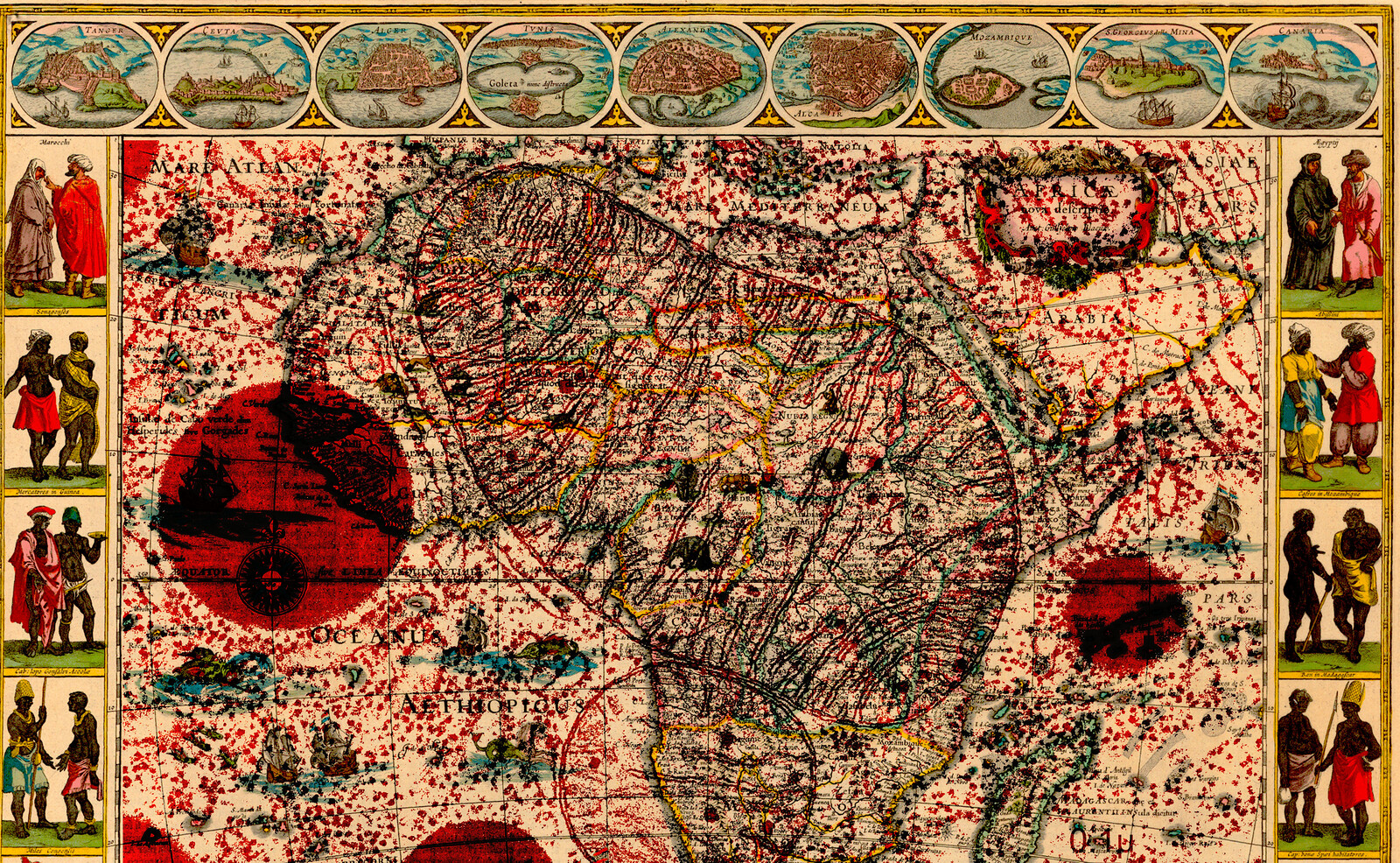

In God’s design, light is crucial. It gave form to the Earth and filled the void; because of the separation between light and darkness, the rest of the plan of creation became possible. Who, then, is this woman singing that song about that house, that dwelling “erased behind the frontiers of darkness”? Who is she who wishes to reverse all of God’s design? Is she even human? And what does she replace it with? What is her design for the world?

The funny thing about devils and demons—at least the way they are understood in popular culture—is that they never really try to undo God’s design of the world. They instead try to control it by manipulating humankind, but that’s not exactly the same thing. Why didn’t Satan try to gain control of all plant life, for instance, and use it to attack humans and subjugate them? In the popular imagination, it seems that the devil, however he’s called, accepts God’s order of things; he lures and seduces and leads humanity astray, but that’s just about it. He competes in order to take over, but does not propose a different plan, a different design.

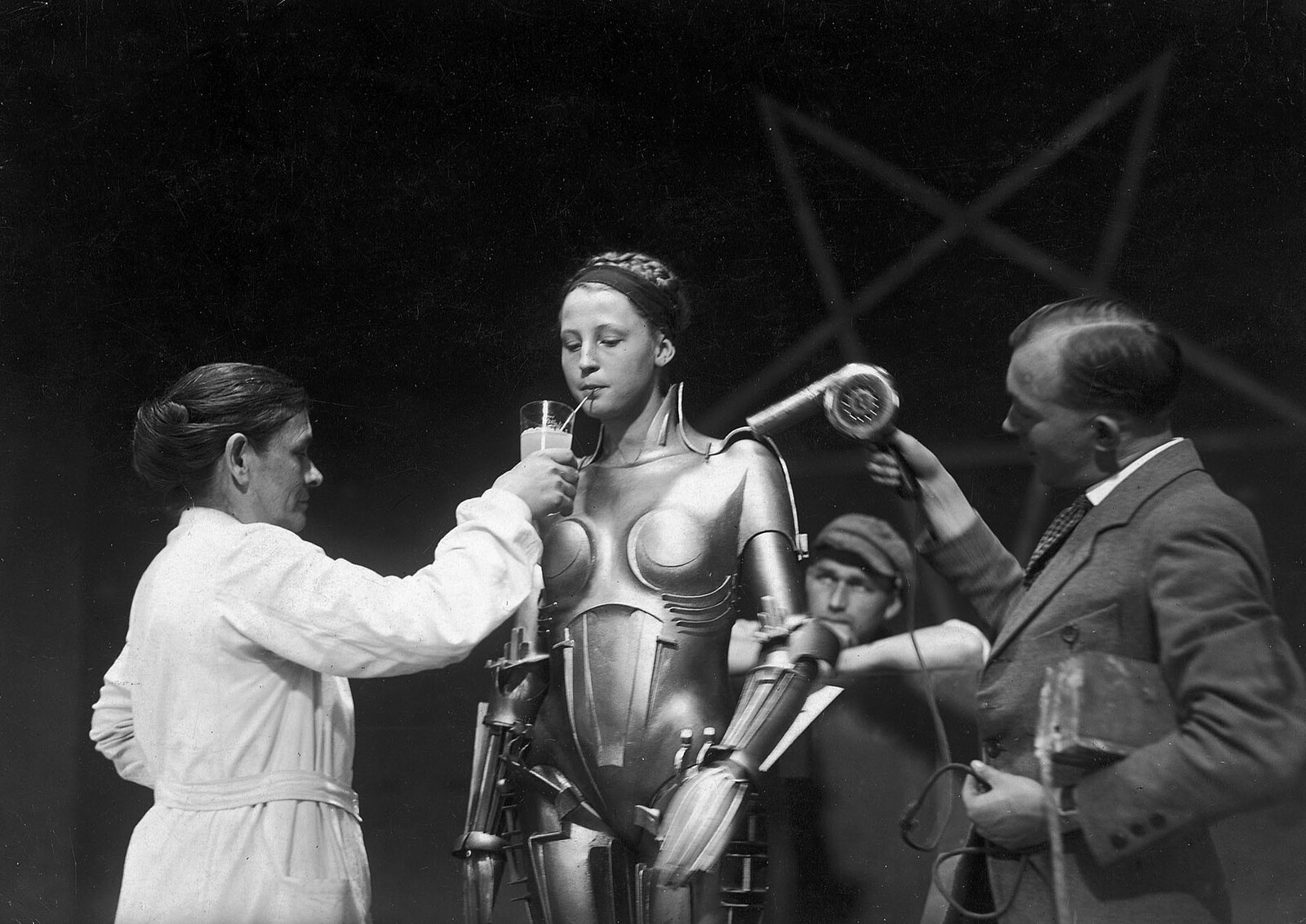

There is one exception though: the “other” woman, the first woman, Lilith. In the bible, when God created Adam, it was not only Adam he created: “So God created man in His own image; in the image of God He created him; male and female He created them.”1 The shift in pronouns, from “him” to “them,” suggests that there was a female as well, and that she was equal to the male because she was created from the same substance as the male and at the same time. Her name was Lilith, and she is associated with the night. Her name in fact shares the same root with the word “night” in Arabic (L/Y/L, ليل), and she still lives on in popular culture as the Succubus, or in Arabian mythology “Qarinah” (قرينة), an old silent woman connected to every man who appears in dreams. Lilith refused to be subservient to Adam, so she grew wings and flew out of Eden. She coupled with the demon Samael and begot hordes of demons until God castrated Samael and made Lilith eat her children. Lilith’s domain is the night, where and when she roams, to have sexual encounters with sleeping men and to prey on pregnant women, attempting to steal their unborn babies.

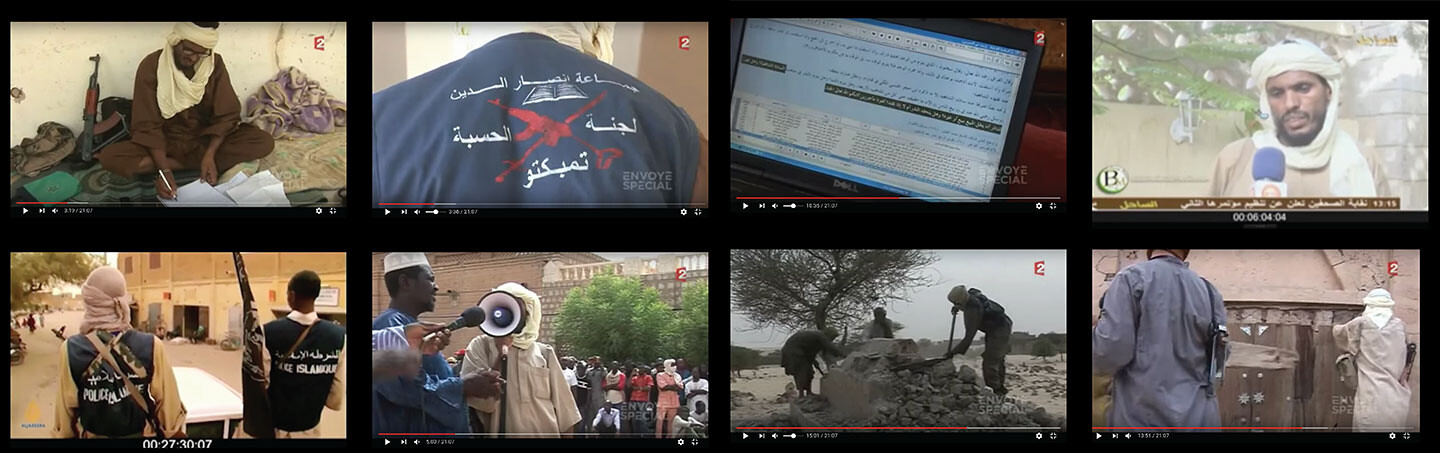

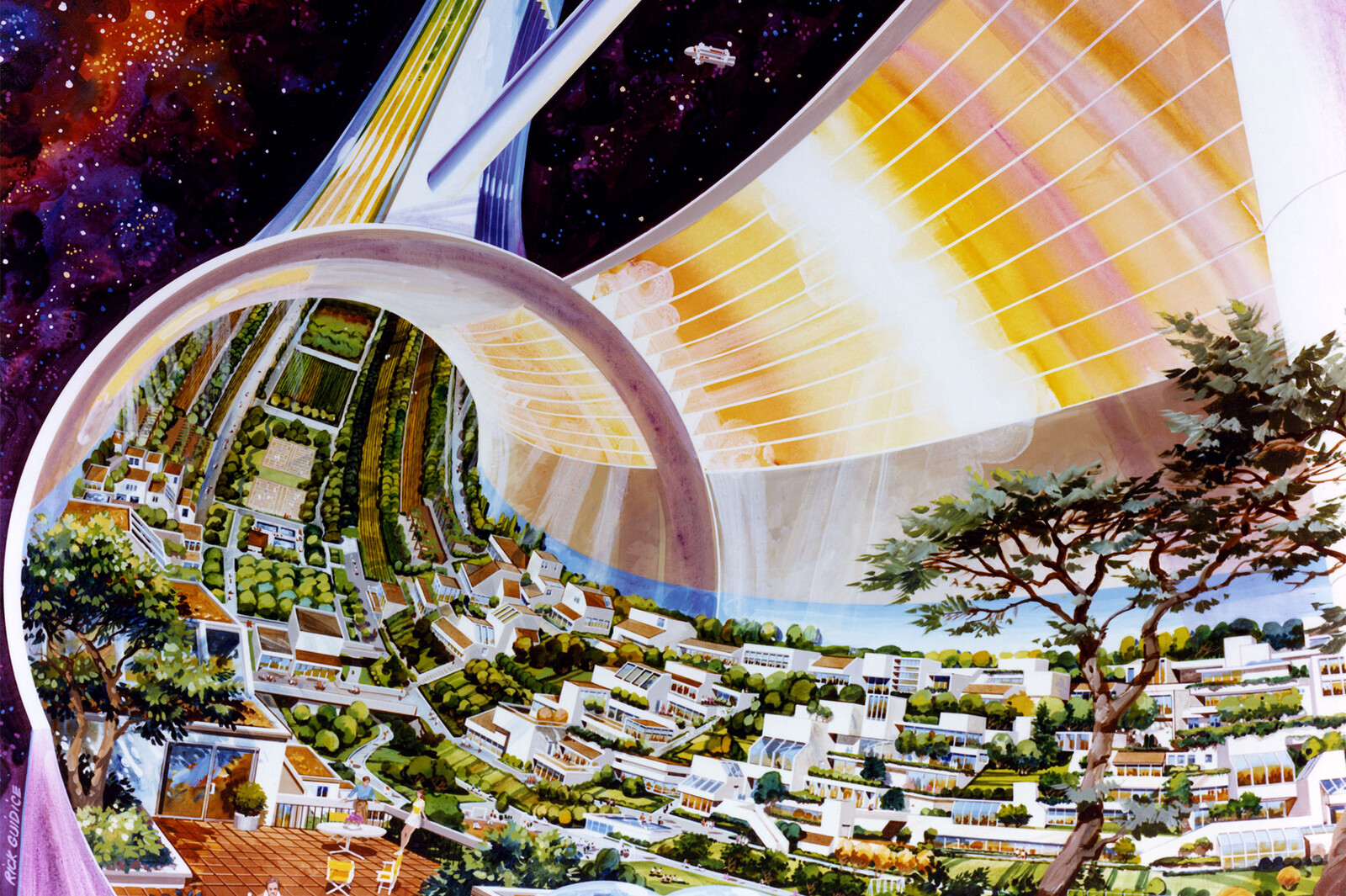

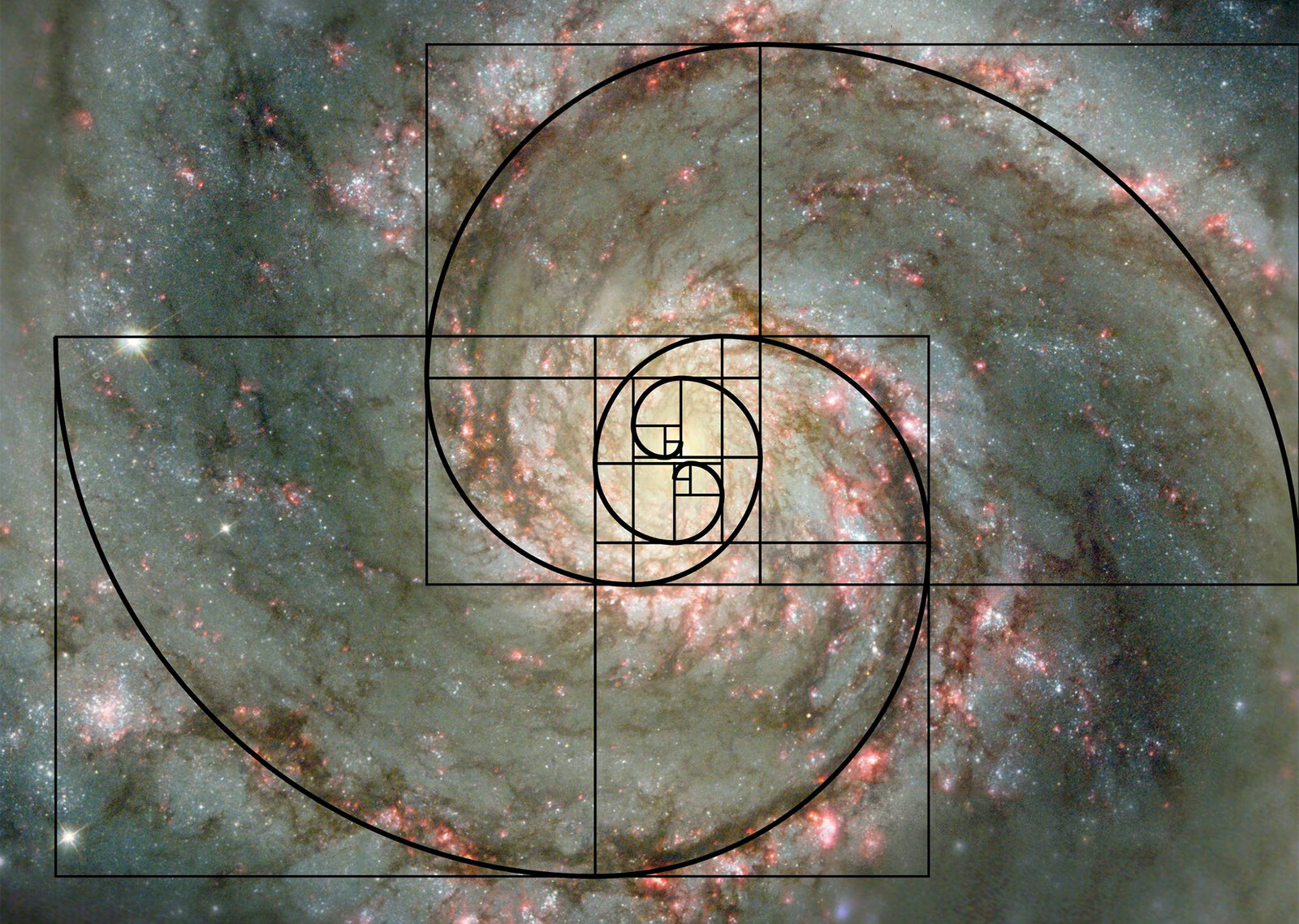

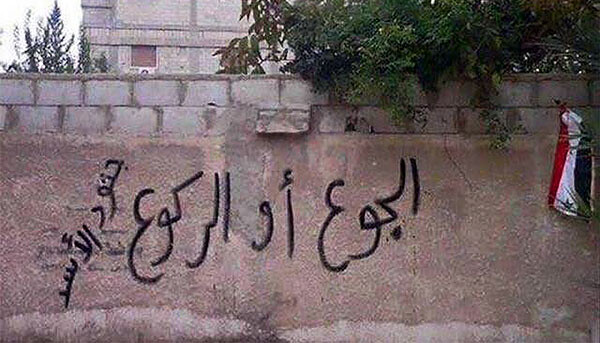

A graffiti in Syria reads “Go hungry or kneel,” in other words, “Surrender or face Hunger” and is signed “Assad’s Soldiers.”

Lilith’s domain is exactly what God tried to suppress and banish from His design: formlessness, void, darkness. One might think that it was probably a good thing, what God did, but if we think of this void not as pure emptiness but rather as something containing millions of possible universes, then a million “what ifs?” spring to mind. This is precisely what Lilith has to work with: millions of possibilities, millions of other universes that do not necessarily begin with “Let there be light,” where humankind is not necessarily at the center of all creation (and knowing why Lilith flew away from Eden, universes where Man, or the male element, is not necessarily “on top”), where life is not necessarily intermingled with death, love with hate, war with peace; a gentle universe where it does not hail violently on defenseless parsley leaves. This universe is one where the foolishness of creation, God’s design, the design that we’ve been told for thousands of years is perfection, is replaced by something else, let’s call it “tenderness”, or “Hanaan” (حنان ) in Arabic; a universe where things long for each other, where everything waits for the other, listens to the other, and lets the other grow, separate, then return in an endless dance, the dance of life.

Lilith’s design is not one of control. She wanted to be free, to liberate herself from the control of the one who was supposedly created as her equal. In order to do so, she first had to blaspheme; by pronouncing the Tetragrammaton she was able to grow wings and escape to the other side of the world that God designed where millions of other possibilities lay dormant. But in order for these possibilities to come to light, so to speak, the existing order, the order of domination of the equal by his equal, had to be undone; and this is, I presume, the real purpose of the nightly wanderings, the hauntings, the silence. This is the real meaning of the “furthest house erased behind the frontiers of darkness,” where light and time are erased, or where everything is undone in order to start anew.

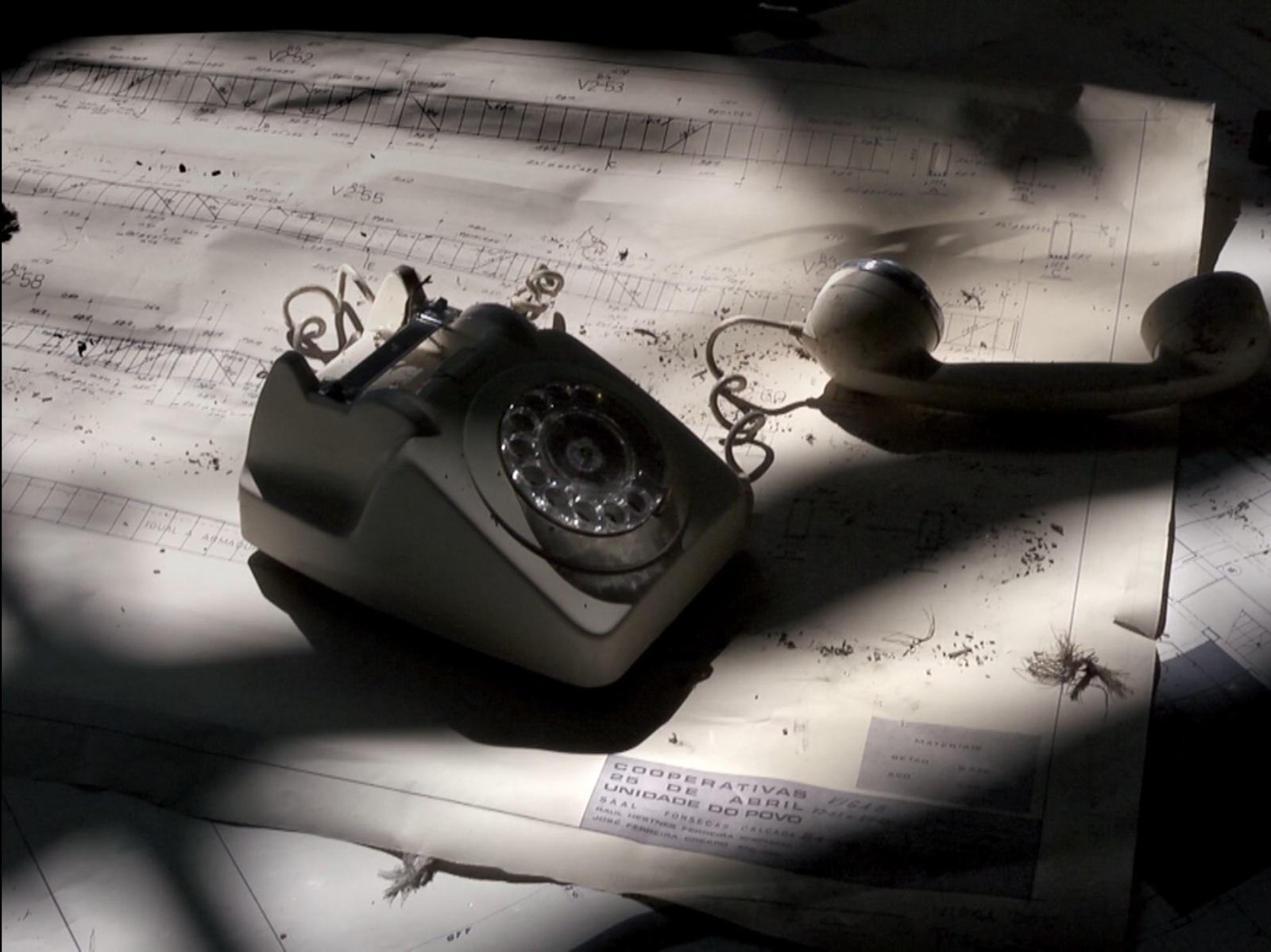

A facebook photo of demonstrators in the proximity of Kafranbel, Syria.

III

O you who fly in (the) darkened room(s),

Be off with you this instant, this instant, Lilith.

Thief, breaker of bones.

—Incantation against Lilith, 7th or 8th century BCE, Syria

Undoing the world, God’s Design and opening up all the latent possibilities that were banished into darkness—everything that can be imagined, everything that can be possible—does not go unopposed. In the story of Lilith, it is said that God punished her by making her eat all her children at the rate of one hundred every day. Consequently, the story says that her actions are driven by rage and revenge. Needless to say, this account was written from the side of the established order, from the side of the forces who were victorious, and who are still shaping our world today, dictating what and how we see, listen, smell, taste and touch; how we establish relationships with everything that is outside of us: people, things, nature, the cosmos.

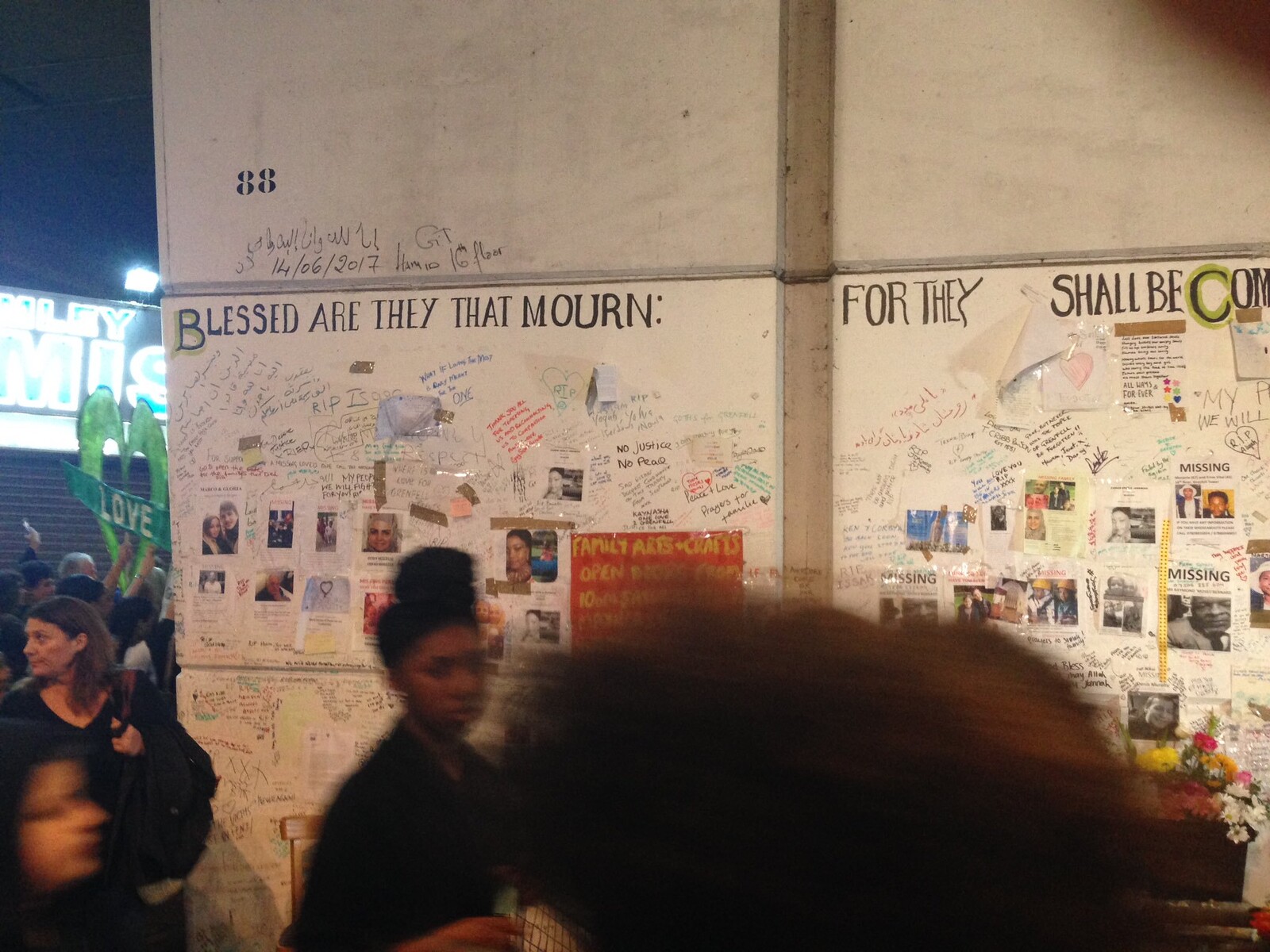

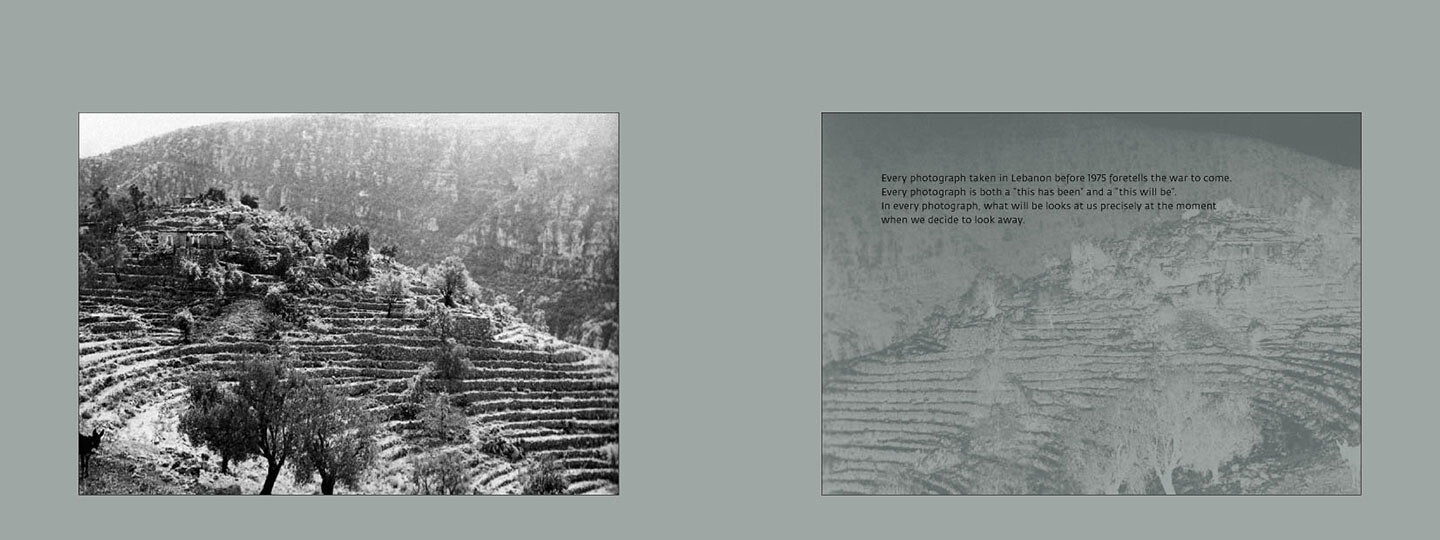

It’s not easy to think of other possibilities, but there are always moments of lucidity. On October 14th 2011, in a small village in Syria called Kafranbel, a banner was held by the inhabitants during a demonstration. The banner read:

Down with the regime and the opposition…

Down with the Arab and Islamic Nations…

Down with the UN Security Council…

Down with the world…

Down with everything

Occupied Kafranbel 14 10 2011

In the photo documenting the event, we can see the villagers holding the banner and making an upside-down V-for-victory sign with their fingers. After that date, “Down with the World” graffiti was spotted in different cities around the world: Cairo, London, Baghdad, and so on.

The banner sounds nihilistic, bitter, politically naïve even. At first glance, one would think that it was written by people who have reached the bottom, the last level of desperation. But the moment of an absolute absence of hope can usually lead to a moment of absolute clarity. The Syrian revolution started as peaceful protests against a dictator. The response of his followers was “Bashar [Assad] or we will burn Syria.” And they did. While the world was negotiating with Mr. President, Destroyer of Cities, talking about a “peaceful solution,” worrying about ISIS before ISIS even existed, organizing “peace conferences” with self-proclaimed oppositions, sending weapons to different factions, refugees were being treated as if they were garbage, politely referred to as a “problem” to be dealt with. Someone who has lost everything, who takes a perilous journey across seas, forests, borders, cities and security forces to finally arrive to his or her coveted destination only to discover that he or she is merely a “problem”… The world order that allows for such a thing to happen should be destroyed and trampled under foot. This order of things should be undone—and this is what the banner is saying. It is not nihilistic; it is an absolutely viable political program. The precise moment that allowed the residents of Kafranbel to see the truth of the world is the moment that allows the rest of us to think of other possibilities, of other worlds where such things are simply not possible.

IV

I speak to you over cities

I speak to you over plains

My mouth is against your ear

The two sides of the walls face

my voice which acknowledges you.

—Paul Éluard

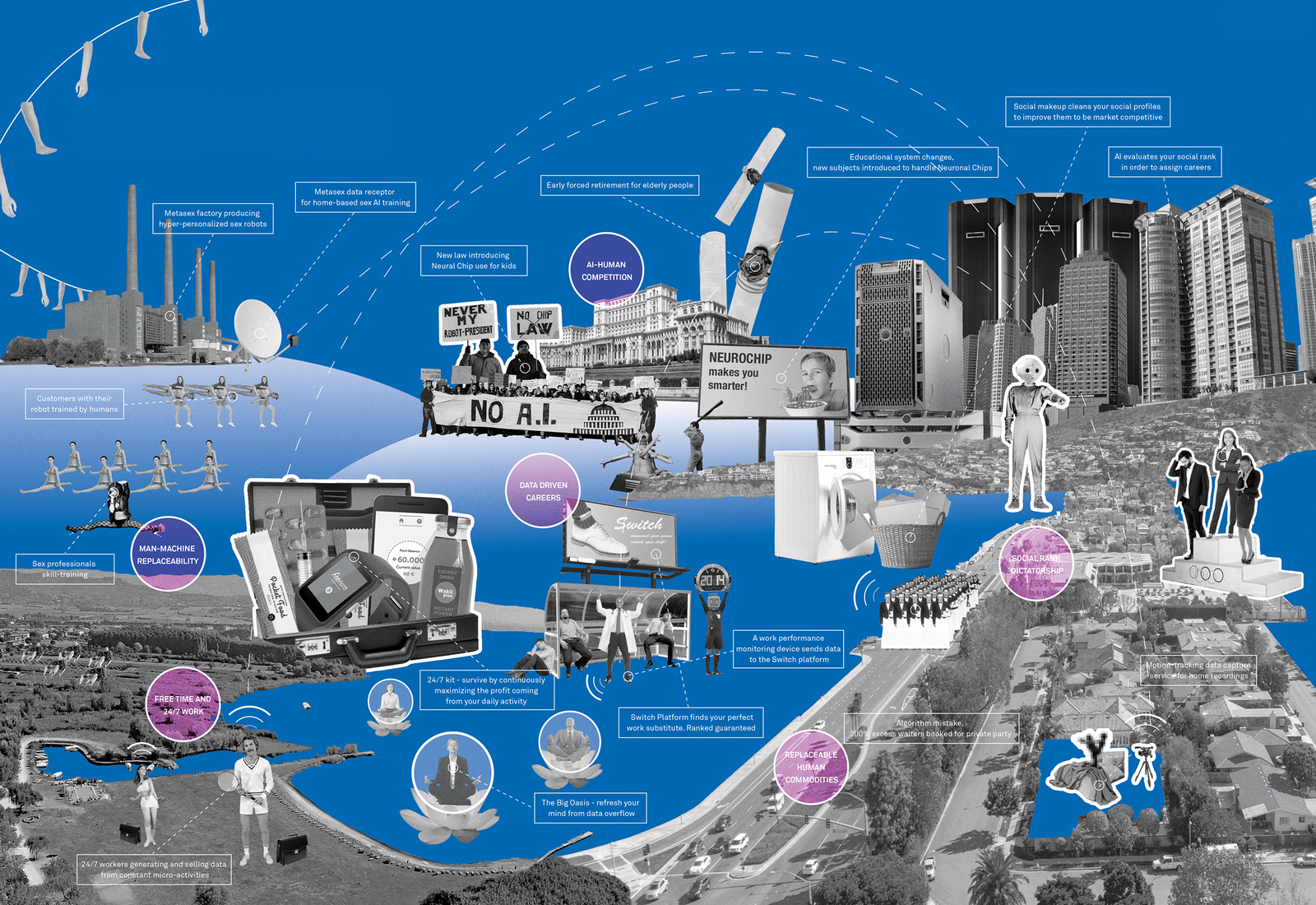

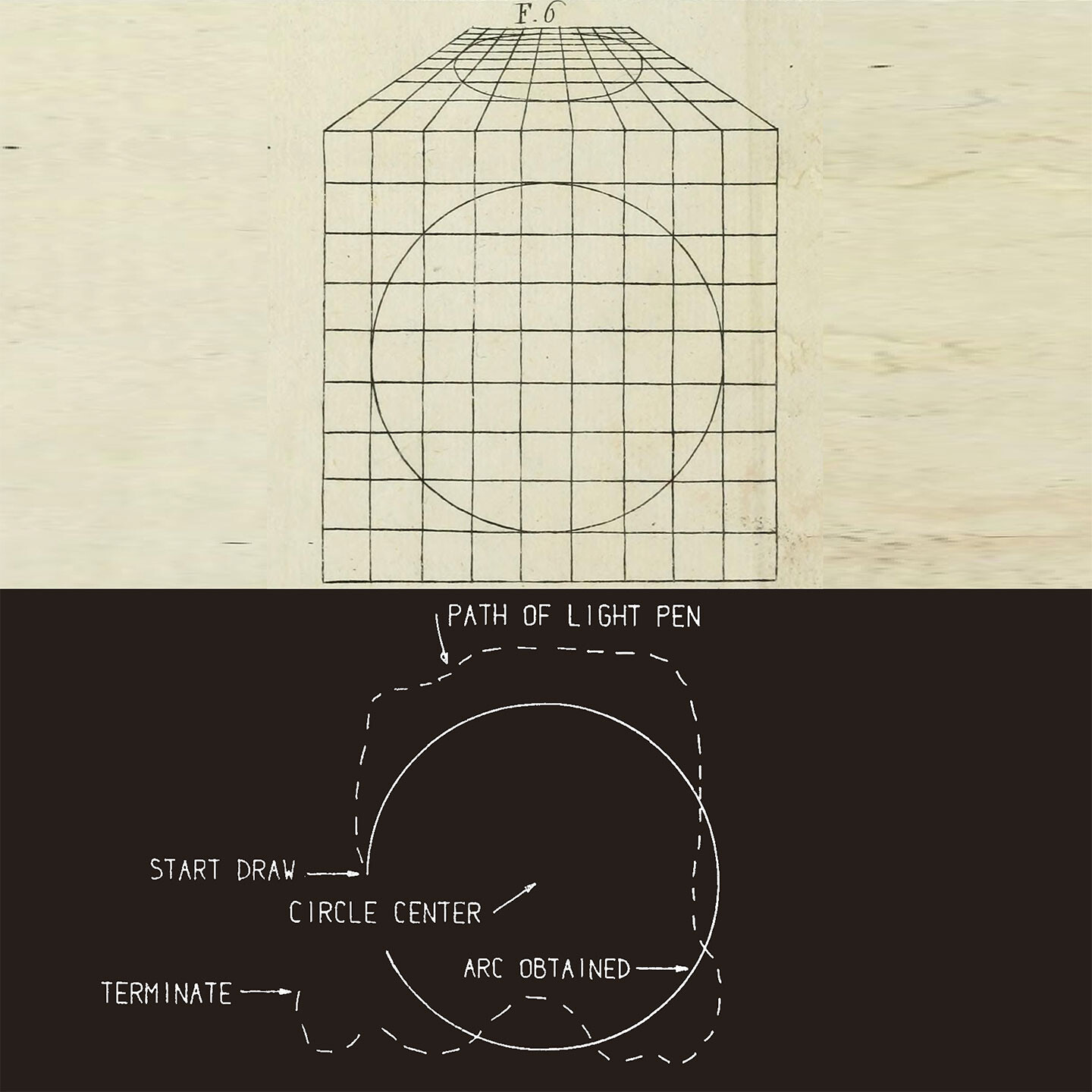

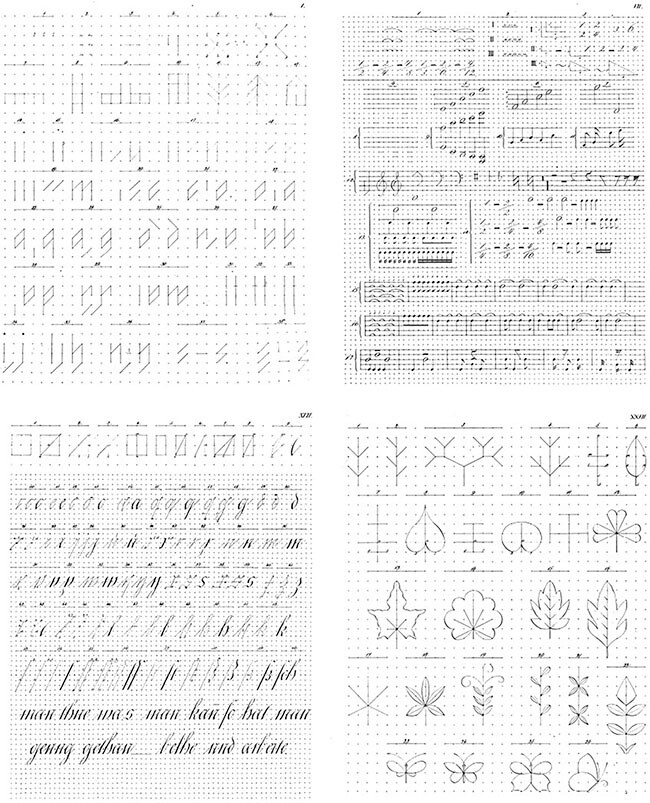

Undoing the world means unlearning everything that we were taught; from the way we see to the way we hear and smell and touch. Everything. Could design, as a specific practice, play a role in that plan? It is possible, but it needs to stop believing in the world-as-it-is in order for that to happen. Design needs to let go of the primacy of the individual, something that is so deeply imbedded in the idea of design itself, or else it’ll remain stuck in creating objects of comfort (what is comfort? Whose comfort?) that would “make life better.” I am not advocating for social design or the social responsibility of design; if we are to undo the world, then the first thing to unlearn is all that what we have been taught about the individual, his completeness, his well being, his emotions, his states, his sociality. Instead of the hermetic individual who finds it increasingly difficult to inscribe themselves in the world, we should opt for another mode of inscription, that of an ongoing, incomplete, enriching conversation that would blow up the borders between us and the things of the world. Or as Friedrich Hölderlin once put it, “Cette conversation que nous sommes.” “This conversation that we are.”

Genesis 1:27

Superhumanity is a project by e-flux Architecture at the 3rd Istanbul Design Biennial, produced in cooperation with the Istanbul Design Biennial, the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea, the Govett-Brewster Art Gallery, New Zealand, and the Ernst Schering Foundation.

Category

Subject

Superhumanity, a project by e-flux Architecture at the 3rd Istanbul Design Biennial, is produced in cooperation with the Istanbul Design Biennial, the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea, the Govett-Brewster Art Gallery, New Zealand, and the Ernst Schering Foundation.