Perhaps you have been struck by the frequency and regularity with which people find it necessary to state what one might think was the most obvious thing in the world: that they are human beings, or that they would like to live like them.

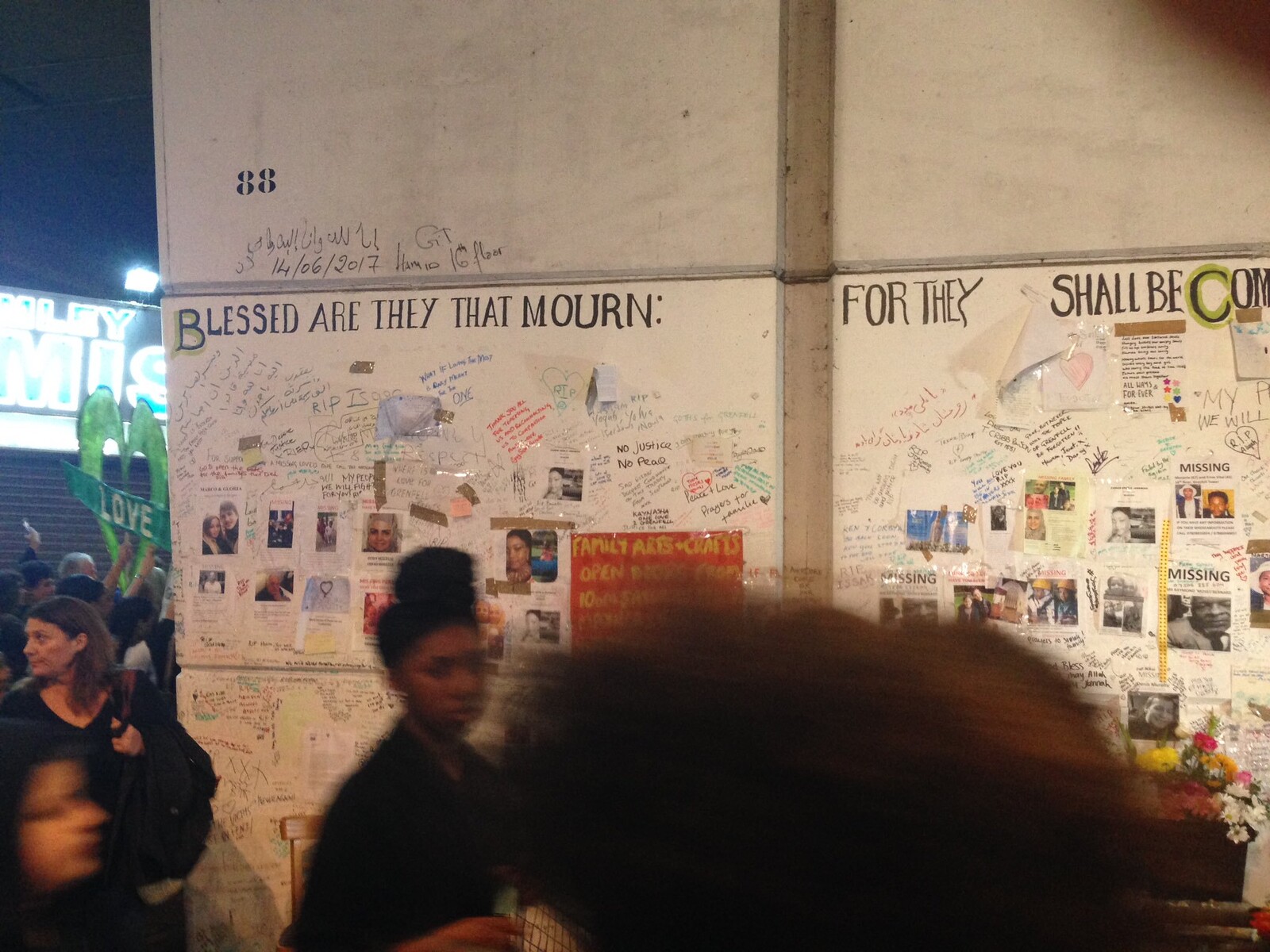

Here’s an example from the front lines of the so-called “refugee crisis” in Europe last March: “‘May God take his revenge on them—everyone who did this to us—from whatever country they come from,’ said Raife al-Baltajy, a Syrian from near Aleppo, as she waited for a bus with her family. ‘May god take his vengeance out on them. Isn’t it sinful? Are we animals? Or are we human beings?’ She said she had been living in Syria for four years under the shelling, but traveled to Turkey, then to the Greek island of Lesbos, where she took a ferry to the mainland and on to Idomeni.”1

Or this claim from another Syrian refugee who spoke out from his new home in the United States: “‘I was born as a human and raised as a human. I have been in some situations that made me feel not like a human,’ [Refaai Hamo, a civil engineer] said. ‘I would like to grab any opportunity I can to prove I am a human being and if I don’t have that opportunity, I refuse to live anywhere I don’t feel like a human.’”2

How do we understand this repeated need of people in situations of displacement, conflict, and injustice, to ask others whether they, the speakers, are in fact human, which is to say, their need “to prove I am a human being”? What is going on when people say this? It seems obvious, but in fact it’s one of the most complicated, enigmatic, unstable things that can possibly be said. We should not take its possibility for granted.

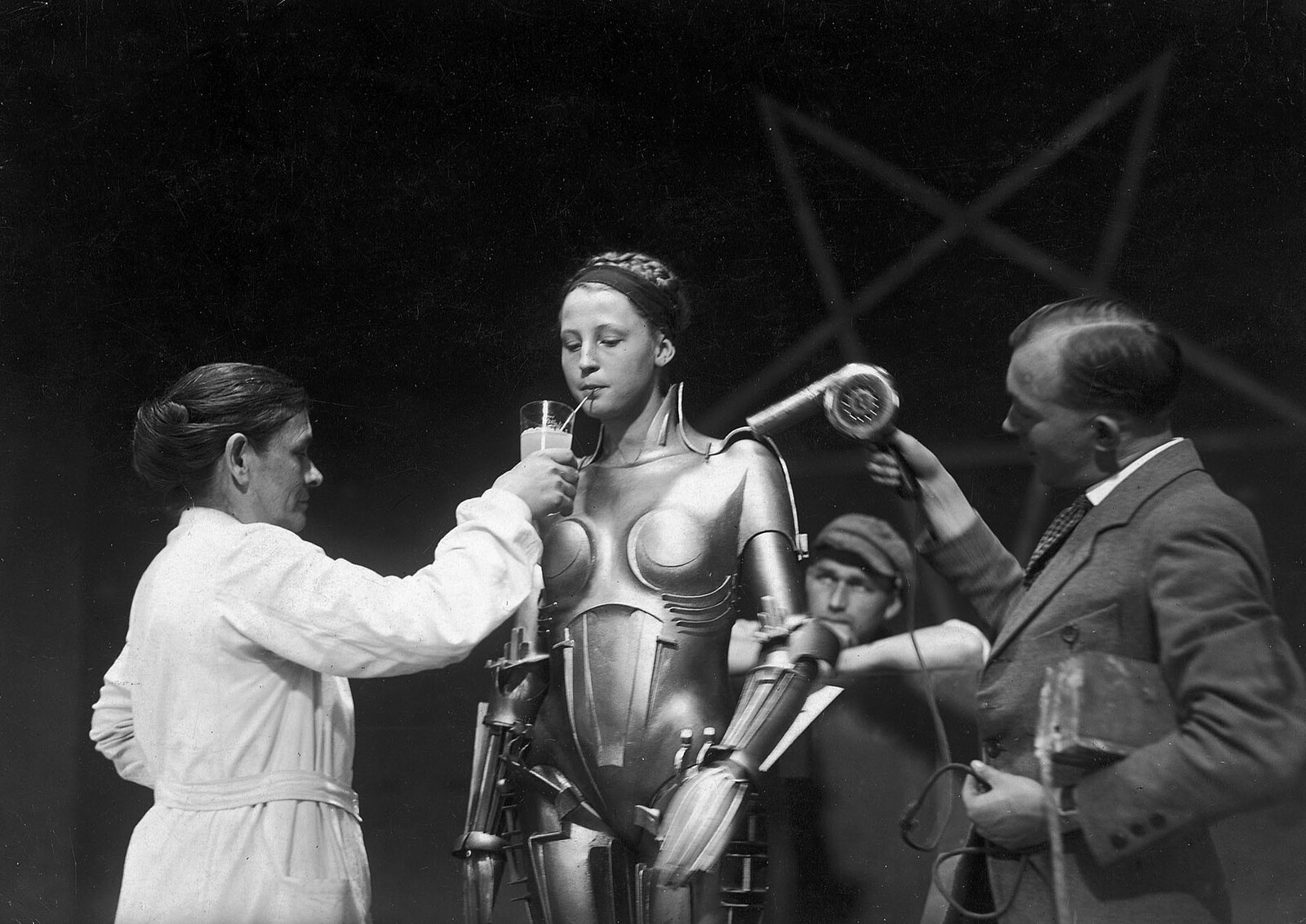

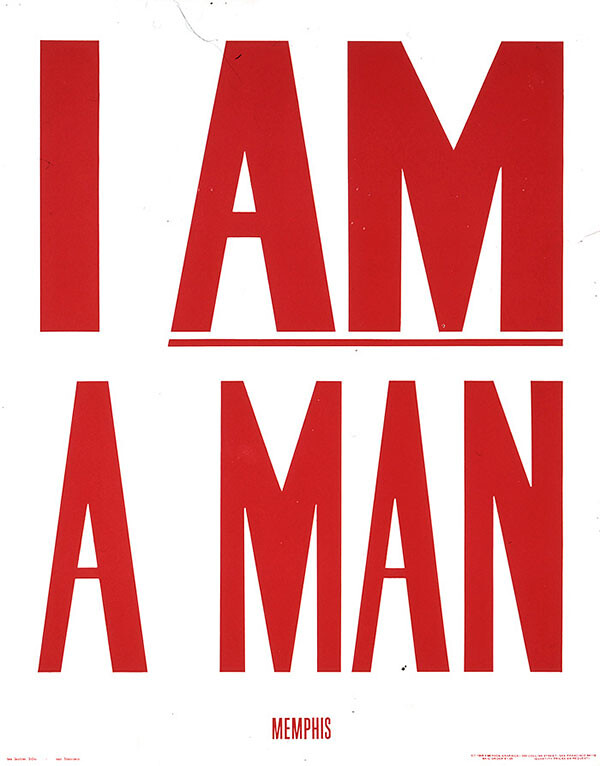

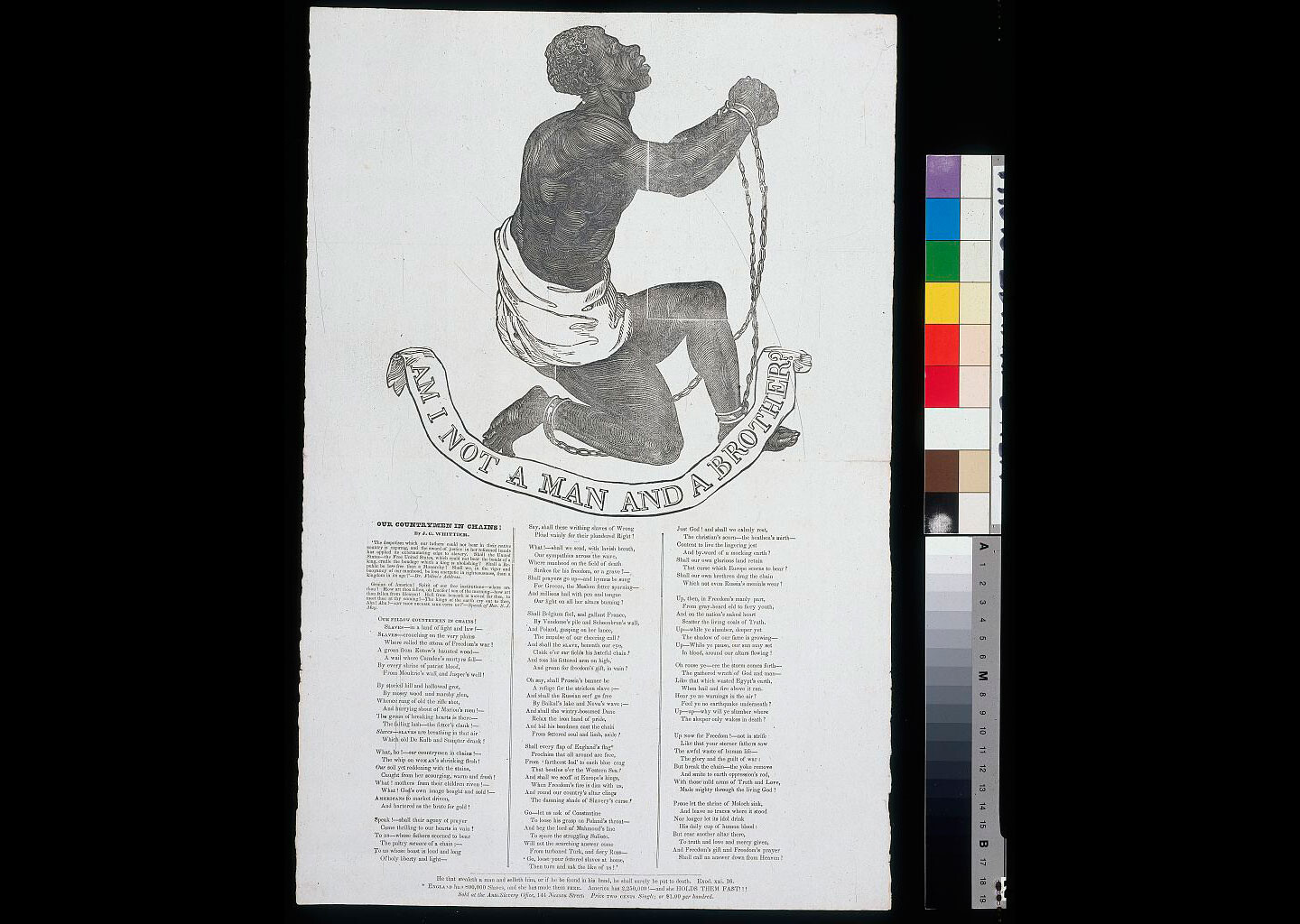

That said, people have been saying it, more or less, for a while. Versions of the claim have a long history—think back to Josiah Wedgewood’s famous anti-slavery medallion of 1787, featuring a shackled African figure knelt in a plea and bearing the inscription “Am I not a man and a brother?,” or to the even more economical signs borne by the Memphis, Tennessee sanitation workers on strike in the spring of 1968, “I am a Man.” This rich provenance makes the utterance somehow even more perplexing: haven’t we learned this yet? Why do people still need to say this? What accounts for the persistence of this claim?

To begin to understand and appreciate these words, “I am a human being,” we need to back up and ask just what sort of speech act is being performed here. I will call it a claim, whether it’s formulated as a question (“Am I not …”), a desire (“we want to live like …”), a simple declaration or an apparent tautology (“I am a …”). In each case, the statement makes a claim, and a claim on others.

I would suggest that rights, especially what we call human rights, are better treated as things we claim rather than things we have. This may seem like a minor matter of words but I believe that it has the potential to challenge profoundly the ways we think about and act with the discourse of human rights. It does not weaken the force of these claims to admit that they are only, or just, that, claims; in fact, it might make them stronger by making them less essentialist, dogmatic, sacred, or as Michael Ignatieff once put it, idolatrous.3 I think this can help us appreciate a number of things, including: what it means to say that human rights are being “violated,” the fact that what counts as a right—and who counts as a rights-bearer—can and has varied so dramatically over time and place, the common experience that the would-be universality of rights is so hard to grasp, and the fact that rights language can serve to propel campaigns of domination and not just struggles against injustice.

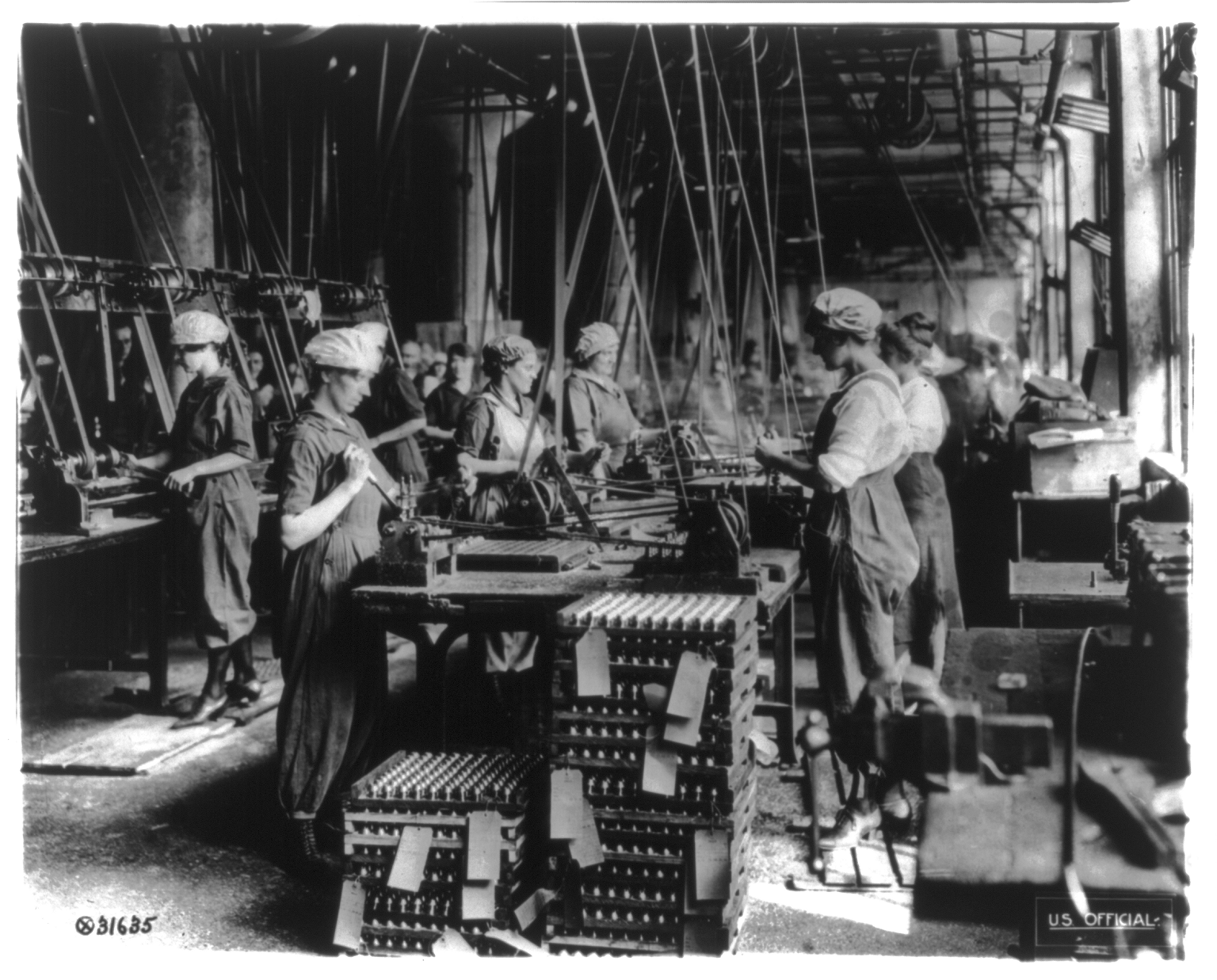

Memphis sanitation workers, the majority of them African American, went out on strike on February 12, 1968, demanding recognition for their union, better wages, and safer working conditions after two trash handlers were killed by a malfunctioning garbage truck. As it dragged on through March, with the Memphis mayor refusing to negotiate, the strike gained national attention. As they marched, striking workers carried copies of a poster declaring “I AM A MAN,” a statement that recalled a question abolitionists posed more than 100 years earlier, “Am I not a man and a brother?”

A few years ago, introducing the mammoth photobook The Face of Human Rights, Walter Kalin economically summed up the contemporary status of his topic with this formulation: “Human rights are the product of an historical process which has not yet reached completion.”4

Here the modesty of the concession to history is balanced, or even overwhelmed, by the confident faith in a progressive expansion signaled by the little phrase “as yet.” The fact of incompletion is paradoxically the sign of more to come.

And yet we could detach this narrative of ongoing accomplishment from its teleology and see in it an important insight about human rights as a thought and practice: in spite, it seems, of their would-be eternality and universality, human rights are structurally incomplete, without fixed limits. This happens not despite this aspiration to universality, but because of it. The universe of their extent is not given in advance, and in fact we could say that the struggle to define its extents—which is in fact the struggle to determine who or what is and is not the subject or bearer of those rights—constitutes the story and the history of human rights. Because rights are a matter of claims, which is to say, disputations, and because those claims require evidence and demand assent, the subjects and the borders of rights are structurally in flux.

The contemporary world offers at least two contradictory answers to the question of how that “process” is coming along.

On the one hand, violations of rights seem more widespread, more visible, and less adequately answered than they have been in a long time. The civil war in Syria, with videotaped sarin gas attacks and an archive of torture photos on one side and mass executions of prisoners heralded by the executioners on another, plus the civic activists attacked by both, offers a convenient figure of this. Likewise the so-called “refugee” or “migrant crisis” that is at least in part the result of that war and its extraordinary cruelties. Amidst so much violence and a tide of displaced people, who could possibly speak of human rights?

But on the other hand, rights claims continue to proliferate, with new subjects speaking its language in new dialects and new spaces every day. Many have noted this, some approvingly and some with dismay about the hegemony of the discourse. What matters in this perspective is not simply that rights are being violated but that the assaults are understood, and answered, as violations rather than as mere suffering. Claiming the right to have rights is not the same as actually enjoying them, of course, but it is the claim, and the demand that people be treated as rights-bearers rather than remaining invisible or as victims or recipients of charity, that makes all the difference. The declaration that “we have become citizens, when once we were sheep,” as a resident of Damascus in the early days of the uprising there was quoted saying, echoes loudly, and it is that transformation in status, the eruption of demands out of obedience, dissent out of acquiescence, that would, in this regard, call for our attention.5

But what if this paradox in fact points to something essential that happens when we speak in terms of rights, whether civil or human? It has often been remarked that rights are nowhere more vigorously claimed—or even recognized as such—than in the aftermath of their violation. Given the generally high level of creativity humans have shown in inventing new ways to harm each other, this might indicate that rights claims are constitutively incomplete. Not that they have “not yet reached completion,” but that they cannot—they quite simply cannot reach that destination.

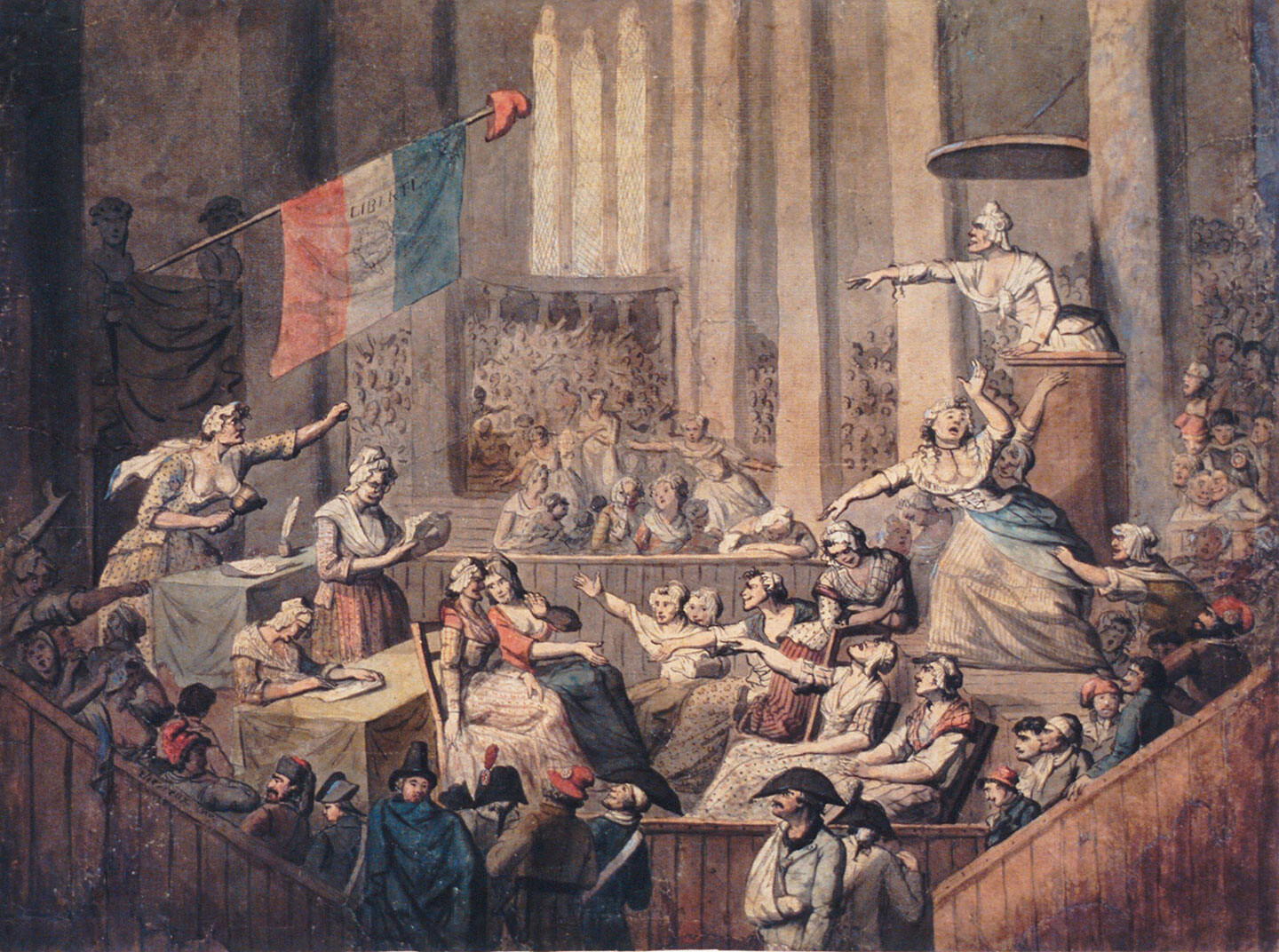

Historian Lynn Hunt argues for a version of this narrative in her important, if sometimes controversial, account of the history of human rights, Inventing Human Rights.6 A prominent scholar of the French revolution, she tells the story of the 18th century emergence of politically powerful notions of autonomy, bodily integrity, and the capacity to identify with others who are not obviously like us. Rights, in this sense of universal claims about what we all share, have a history, which is what she means by “invented.”

She too starts from a paradox: how is it that, without ever defining what a man or a human being was, and in fact intending to limit this category to a small group of white male Catholic property-holders, the French Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen of 1789 turned out to be so contagious in its application, so uncontrolled in its spread? If, as the Declaration begins, “men are born and remain free and equal in rights,” to whom exactly did the phrase “men” refer? The abstraction seems so general as to be useless, imprecise and unenforceable. Deprived of almost all reference to nature or to history, nation or faith or tradition, how could these assertions go anywhere?

Hunt agues that this bland generality concealed a very specific set of assumptions. “Those who so confidently declared rights to be universal in the late eighteenth century,” she writes, “turned out to have something much less all-inclusive in mind. We are not surprised that they considered children, the insane, the imprisoned, or foreigners to be incapable or unworthy of full participation in the political process, for so do we. But they also excluded those without property, slaves, free blacks, in some cases religious minorities, and always and everywhere, women.”7

But the Declaration simply took all that for granted, and what it stated was notable not for its exclusions but for its lack of them—its vague, sweeping, abstract generality. It named its subject simply as “men.” This definitional reticence structured its discourse: no subject was ruled out a priori, even if they might be excluded in fact.

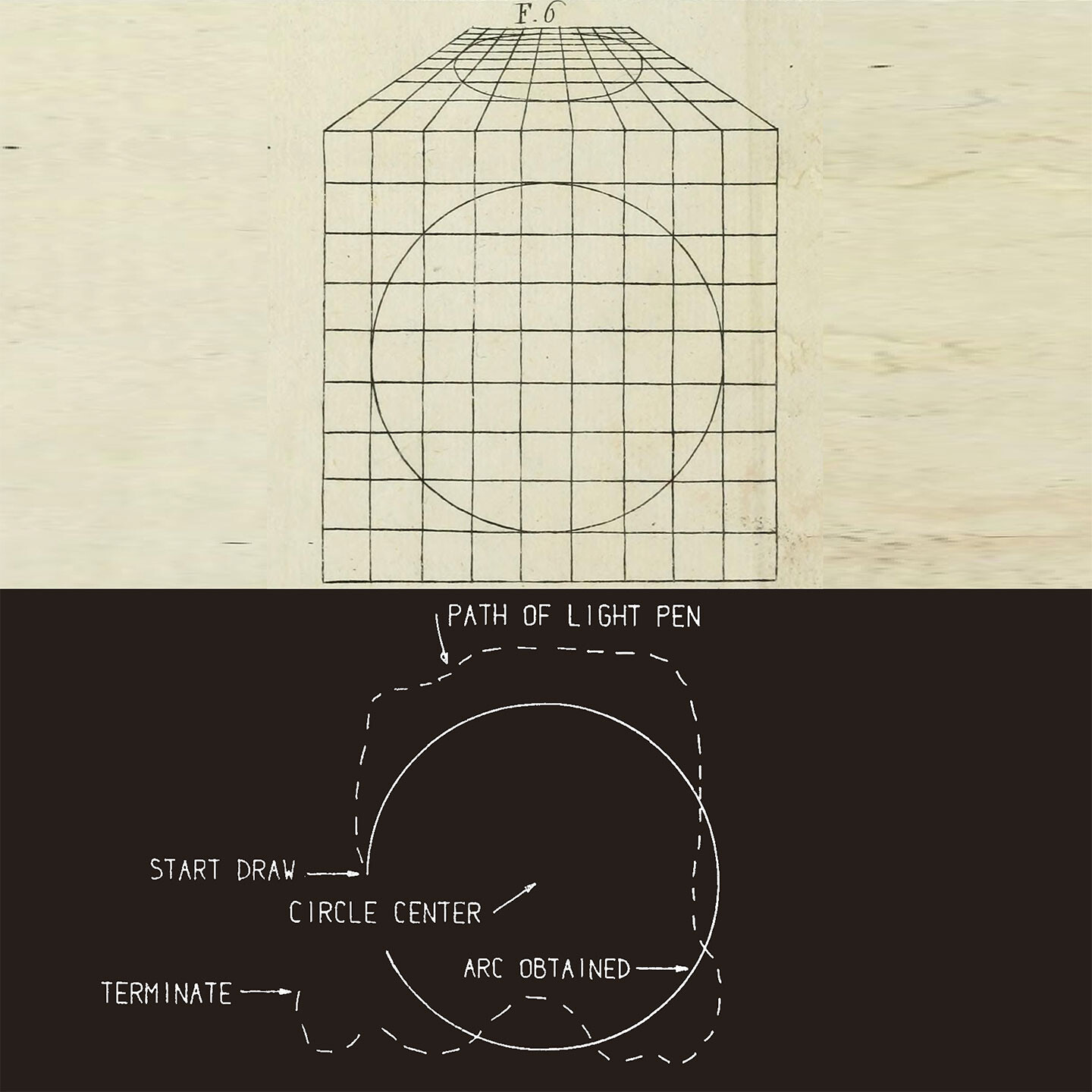

And so something unintended happened. Rights, and claims of rights, began to spread. How did these vague abstractions come to be so productive of concrete, particular, specific effects? Hunt’s answer is that their apparently crippling abstraction and lack of definition were in fact responsible for their viral mobility. Rights ungrounded and stripped of metaphysical justification, rights without pre-given subjects, rights proclaimed “without defining the qualifications for citizenship,” as she puts it, were rights that exceeded their original limitations, spread far beyond their prescribed borders.8

And so the salient feature of articulating grievances and emancipatory desires in terms of the rights of “men” was an implicit commitment to an overflow: without definition and in the absence of all qualifications for having them, rights belong not so much to everyone as to anyone. If it can’t be shared, if it belongs only to me or to one group, it might be a protection or an entitlement, but it’s not a right. Rather than offering a definition of citizenship or human being and then attaching rights to it like a predicate to a subject, the process seems to work in reverse: the rights enumerated are themselves what come to define the man or citizen. This meant that the declaration of rights unleashed an unanticipated, unpredicted, and unpredictable process. For better and for worse. No one knew in advance to whom they referred. Their referent was, structurally, in question, and the political realm was thus revealed as a space of constitutive dispute or conflict: who could take part, who could claim, who counted? These questions are political ones par excellence. Invoking “rights” was nothing more or less than a way of calling existing subjects and definitions into question. Since, as Hunt argues, “rights once announced openly raised new questions—questions previously unasked and previously unaskable,” they constituted a radically destabilizing force. The Declaration put everything into question, and “rights questions thus revealed a tendency to cascade.”9

This happened thanks to the lacuna: “precisely because it left aside any question of specifics, the July-August 1789 discussion of general principles helped set in motion ways of thinking that eventually fostered more radical interpretations of the specifics required. The Declaration,” Hunt reiterates, “offered no specific qualifications for active participation. The institution of a government required movement from the general to the specific; as soon as elections were set up, the definition of qualifications for voting and holding office became urgent. The virtue of beginning with the general became apparent once the specific came into question.” And thus the cascade: “over the next months and years, group after group came up for specific discussion and eventually most of them got equal political rights.”10

Group after unqualified group made their claims, based on nothing more than the projection of an analogy between themselves and those who had already made their own claims. Rights were extended first to non-Catholics (first Protestant men, then Jewish), to free black men, and then to all men in metropolitan France except servants and the unemployed. The tide continued with Toussaint l’Ouverture’s insurgency in the French colonial Caribbean (“I want Liberty and Equality to reign in Saint Domingue,” he said), which led to the abolition of slavery in 1794, and finally with the unsuccessful campaigns of Olympe de Gouges and others for equal rights for women. Each time the grammar and rhetoric of rights claims were repeated in a chorus of new voices—not always successfully, and not always effectively, but repeated and transformed nonetheless.”11

The story of this conceptual and practical movement, born of abstraction, is structured by ebbs and flows. It is a story of conflict, of injustice and struggle, of claims made and sometimes rebuffed and sometimes answered. But it is certainly the story of an outpouring, of an overflow that, although it often followed pre-existing features of the terrain, did not have to. Each new claim came with its own performatives and justifications, articulated new qualifications and challenges, washed away the fixed features of the landscape of status in order to remake the definitions of what was required in order to take part in political life—to remake the political, in fact, by politicizing what hadn’t been political.

Hunt writes: “The notion of the ‘rights of man,’ like revolution itself, opened up an unpredictable space for discussion, conflict, and change.” And it is not over: it is always incomplete, since nothing given prevents the space from contracting or expanding. That is what a “process” means. “The cascade of rights continues, though always with great conflict about how it should flow.”12

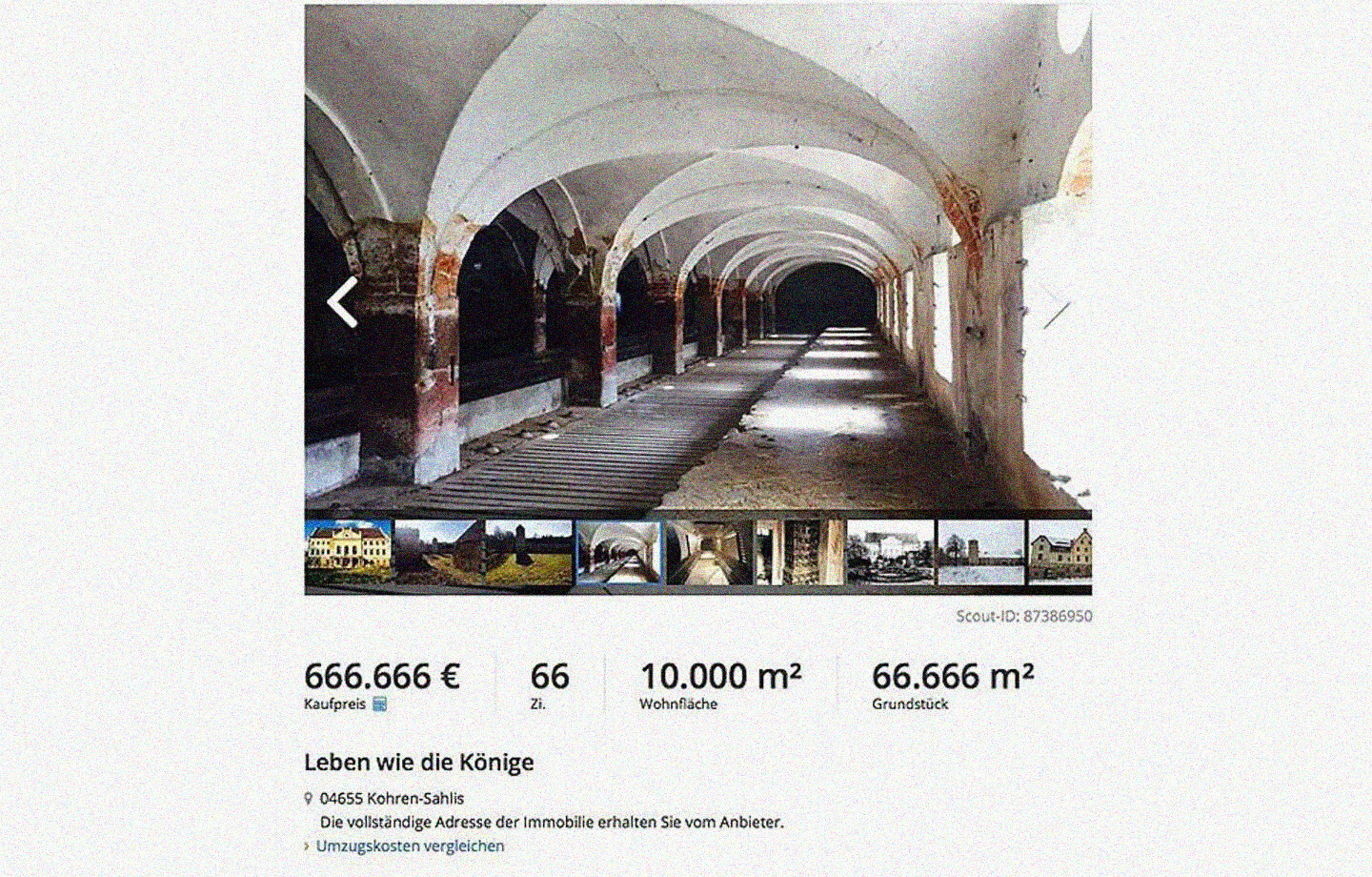

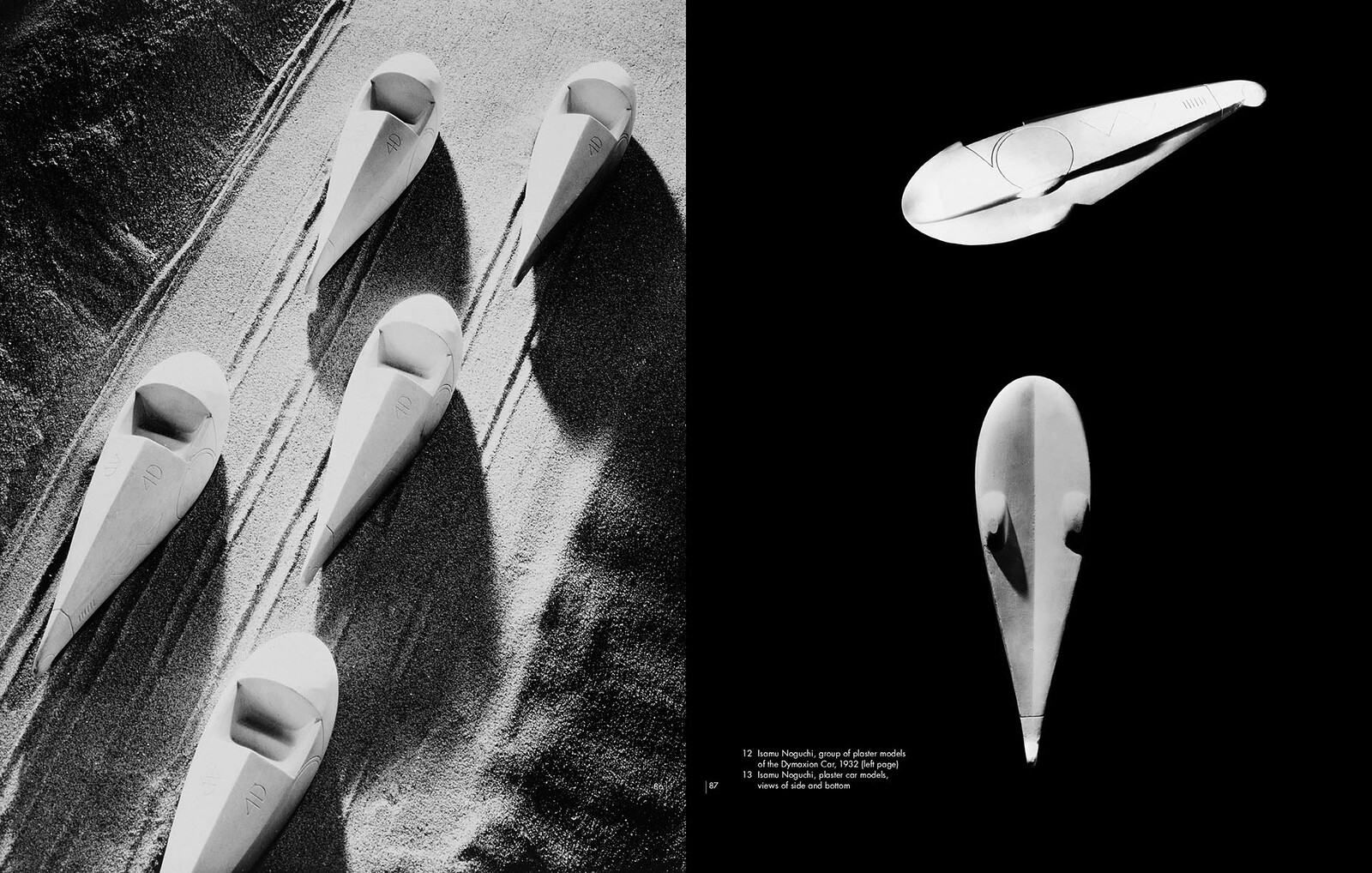

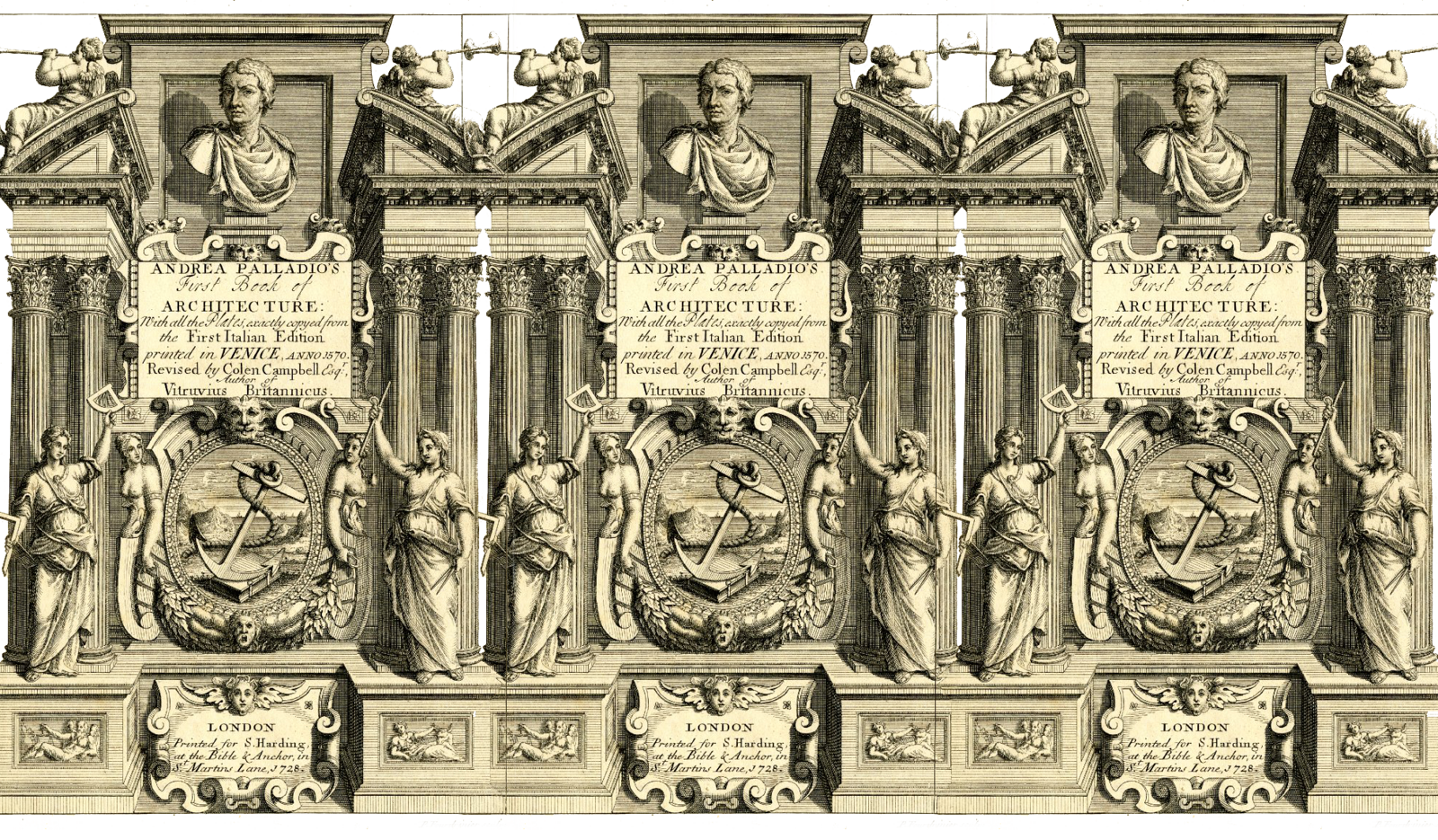

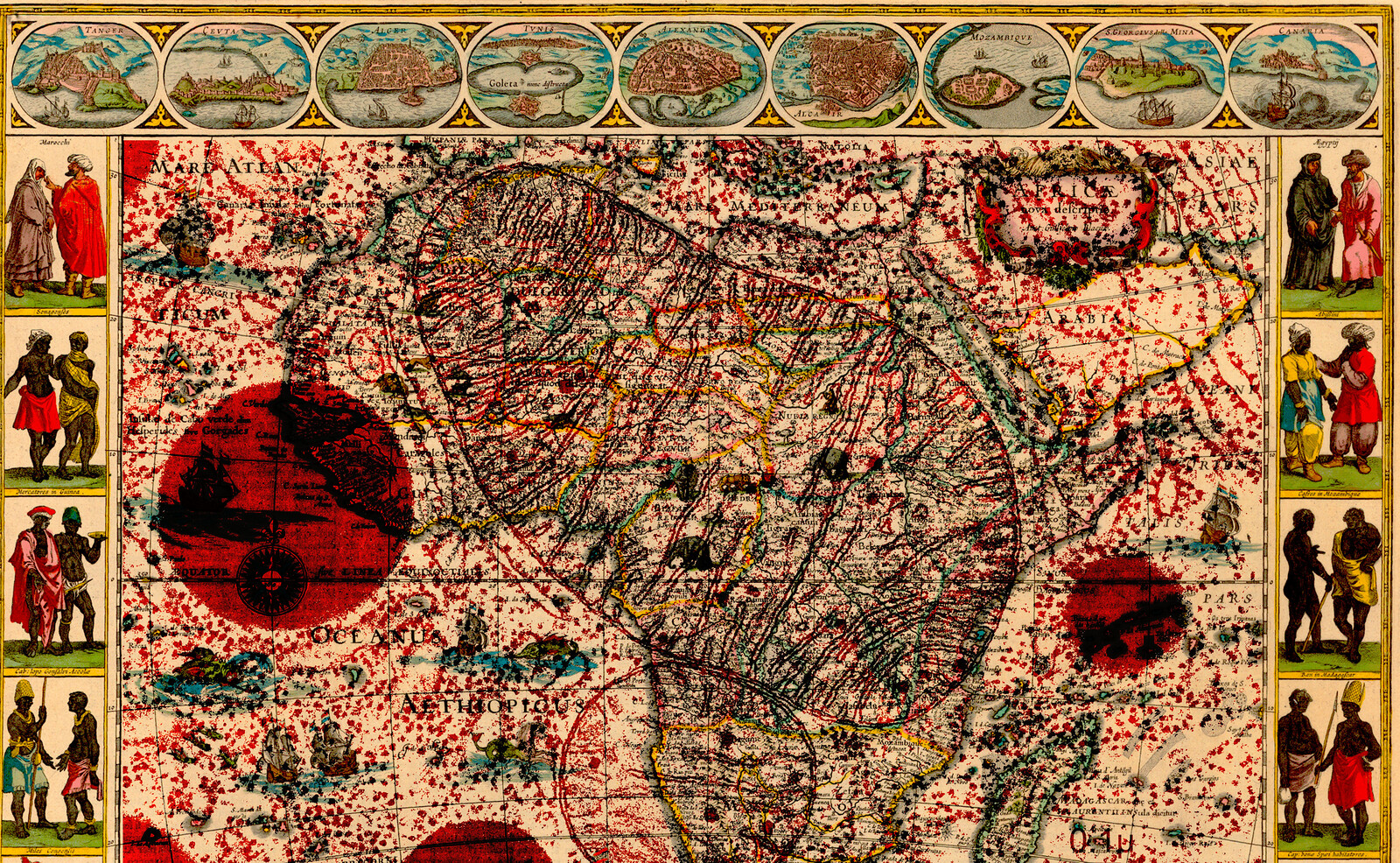

The large, bold woodcut image of a supplicant male slave in chains appears on the 1837 broadside publication of John Greenleaf Whittier’s antislavery poem, ”Our Countrymen in Chains.” The design was originally adopted as the seal of the Society for the Abolition of Slavery in England in the 1780s, and appeared on several medallions for the society made by Josiah Wedgwood as early as 1787. Photo: Library of Congress

This may sound insanely optimistic and out of touch with reality. It’s neither. It amounts simply to the claim that, politically speaking, humanity is an essentially contested category. It would not be overstating things, in fact, to say that politics is, in its richest sense, about this contest.

Because, let’s be clear, the groups of people that Hunt discusses, like the speakers whose demands I began by quoting, have not just been accidentally or inadvertently “left out” of political life. It is not a simple omission, not a matter of haste or a momentary lapse, that excludes them from participation or recognition. At any given moment, there is a line, or lines, demarcating who counts as a member of the community and who doesn’t. This is easy to see when we are talking about citizenship, but the structure extends to any and all such communities. Even ones that proclaim their universal extension and radical openness have to make decisions, conscious or not, about the minimal requirements for inclusion, whether they are seemingly trivial ones like age or species, or seemingly vicious ones like race or gender. The existing features of any political sphere, the constitution of the community, at any given time is premised on exclusion. One cannot wish or theorize this away. One can only put up with it or challenge it. And the story of politics, exemplified by the ebb and flow I’ve retold from Hunt’s historical narrative, is about the challenges and the contests over these lines of demarcation. Or, to put it a bit more carefully, it’s about projects to politicize subjects and topics that have not previously been seen as political, and, in the other direction (lest you think this is always a happy story), about projects to put certain subjects and issues out of political contest, to naturalize or depoliticize them.

So “humanity” is, ironically, as Bruno Latour would say, a thing: “the issue that brings people together because it divides them.”13 We are that issue, precisely because it is not clear who we are. We are the ones deciding, which is to say debating, who we are. Many years ago Claude Lefort put this very elegantly, in an economical and profound critique of the erroneous attribution of a theory of natural rights to the American and French declarations: this masks, he says, “the extraordinary event constituted by a declaration that was an auto-declaration, that is, a declaration by which human beings, speaking through their representatives, revealed themselves to be both subjects and objects of the utterance in which, all at once, they named the human in one another, ‘spoke to’ one another, appeared before one another, and, in so doing, erected themselves into their own witnesses, their own judges.”14

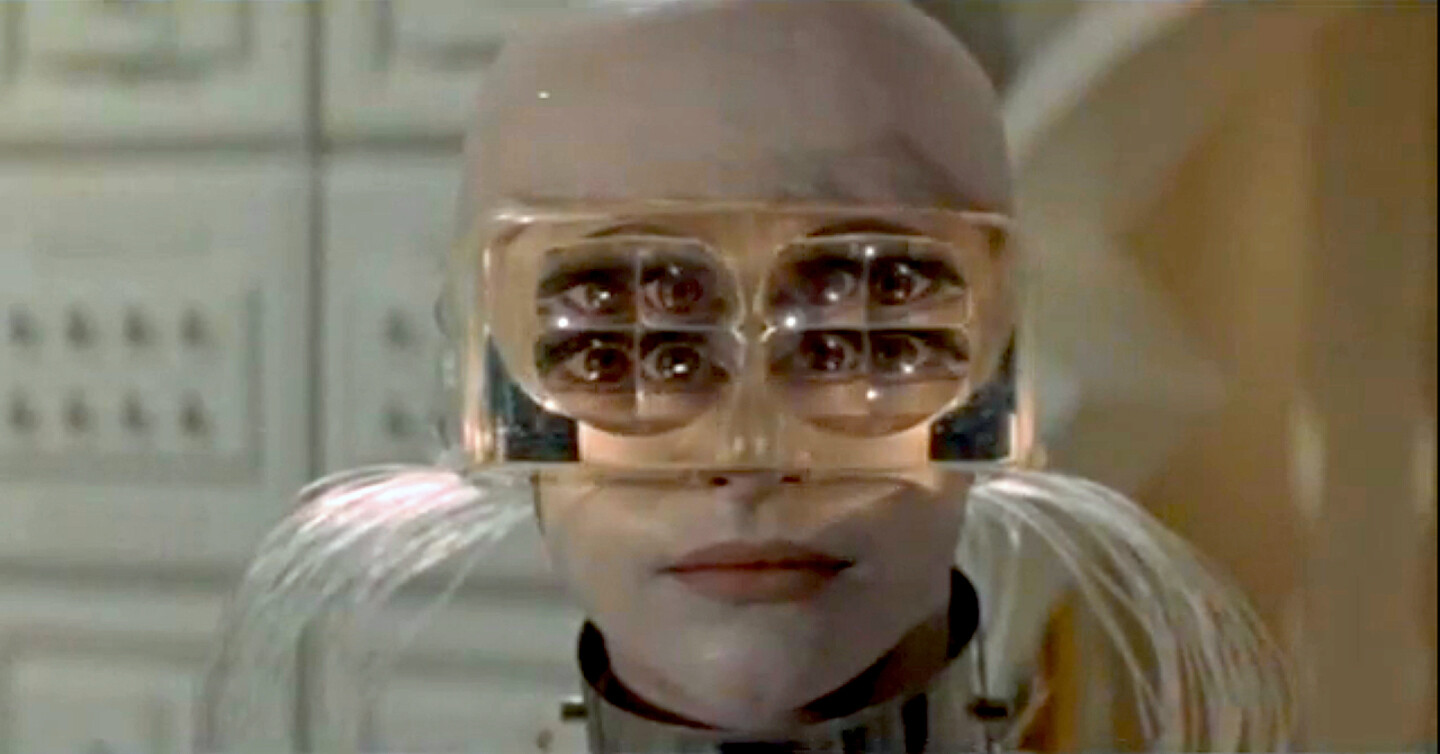

This implies the persistence of the debate about who or what is the subject of human rights, a debate which can go any one of a number of ways at different times. There is division and a debate because who or what is a human being is not a matter of intuition nor of self-evidence; hence, an irreducible part of those claims and that debate will be the presentation of evidence, which is to say that we are in the domain of mediation, representation, and rhetoric—what Latour calls the “long retinue of complicated proof-giving equipment.”

Claims, in other words, require evidence, and the consideration of that evidence is always the task of others. I began with a pair of examples of apparently obvious statements of the sort “I am a human being,” claims that, I’ve argued, are actually far from obvious. In fact, in some cases it’s a wonder that we can hear them at all: how do those who have no standing, whom we do not recognize as one of us, who do not count and do not even appear before us as fellow political subjects, how do they make themselves heard and attended to? These are not rhetorical or overly-dramatic questions: think of how long it took for slaves to be registered or recognized as human beings, a struggle that has still not been definitively accomplished, or for torture to be abolished, also not exactly a done deal. And for good reason, as it were: if membership in the community is premised on the exclusion of others from it, then the identity and self-understanding of those who do count depends precisely on not being those who don’t. So when the excluded say, “count us, we are humans (or French, or whatever) like you,” they are not asking simply to make the space of the community bigger, to add some extra chairs to the table, as it were. They are asking for a new space, a new table, and a new definition of who it is that sits at it. When they are recognized, heard, admitted, the definition of who we all are undergoes a shift. It’s no wonder that these matters are so strongly contested, and that people have to keep contesting them.

See ➝

See ➝

Michael Ignatieff, Human Rights as Politics and Idolatry (Princeton University Press, 2003).

The Face of Human Rights, eds. Walter Kälin, Lars Müller, Judith Wyttenbach (Lars Müller Publishers, 2004), 21.

“The squeeze on Assad,” The Economist (30 June 2011), ➝

Lynn Hunt, Inventing Human Rights (New York: W.W. Norton and Company Press, 2007).

Ibid. Hunt, 18–19.

Ibid. Hunt, 132.

Ibid. Hunt, 145, 147.

Ibid. Hunt, 147, 151. Hunt’s frequent critic Samuel Moyn underlines the power of this argument: “Hunt is most interested in what she repeatedly calls the cascading logic of human rights, whereby those who announced rights were compelled to extend them to Jews, blacks and women (or at least to consider doing so). And when groups initially excluded from humanity were not brought into the fold, as Hunt points out, they sometimes forced the issue. Early feminists like Olympe de Gouges and Mary Wollstonecraft declared the rights of women, while slaves in the French Caribbean demanded liberation.” Samuel Moyn, “On the Genealogy of Morals,” The Nation (16 April 2007), ➝.

Ibid. Hunt, 149–50, 166, 171. Napoleon reestablished slavery in the colonies in 1802, which lasted until 1844.

Ibid. Hunt, 175, 212.

Making Things Public. Atmospheres of Democracy, eds. Bruno Latour and Peter Weibel (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2005), 13.

Claude Lefort, Democracy and Political Theory (Cambridge: Polity Press, 1988), 38.

Superhumanity is a project by e-flux Architecture at the 3rd Istanbul Design Biennial, produced in cooperation with the Istanbul Design Biennial, the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea, the Govett-Brewster Art Gallery, New Zealand, and the Ernst Schering Foundation.

Category

Subject

Portions of this text also appear in The Flood of Rights, eds. Thomas Keenan, Suhail Malik, Tirdad Zolghadr (forthcoming, 2017).

Superhumanity, a project by e-flux Architecture at the 3rd Istanbul Design Biennial, is produced in cooperation with the Istanbul Design Biennial, the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea, the Govett-Brewster Art Gallery, New Zealand, and the Ernst Schering Foundation.