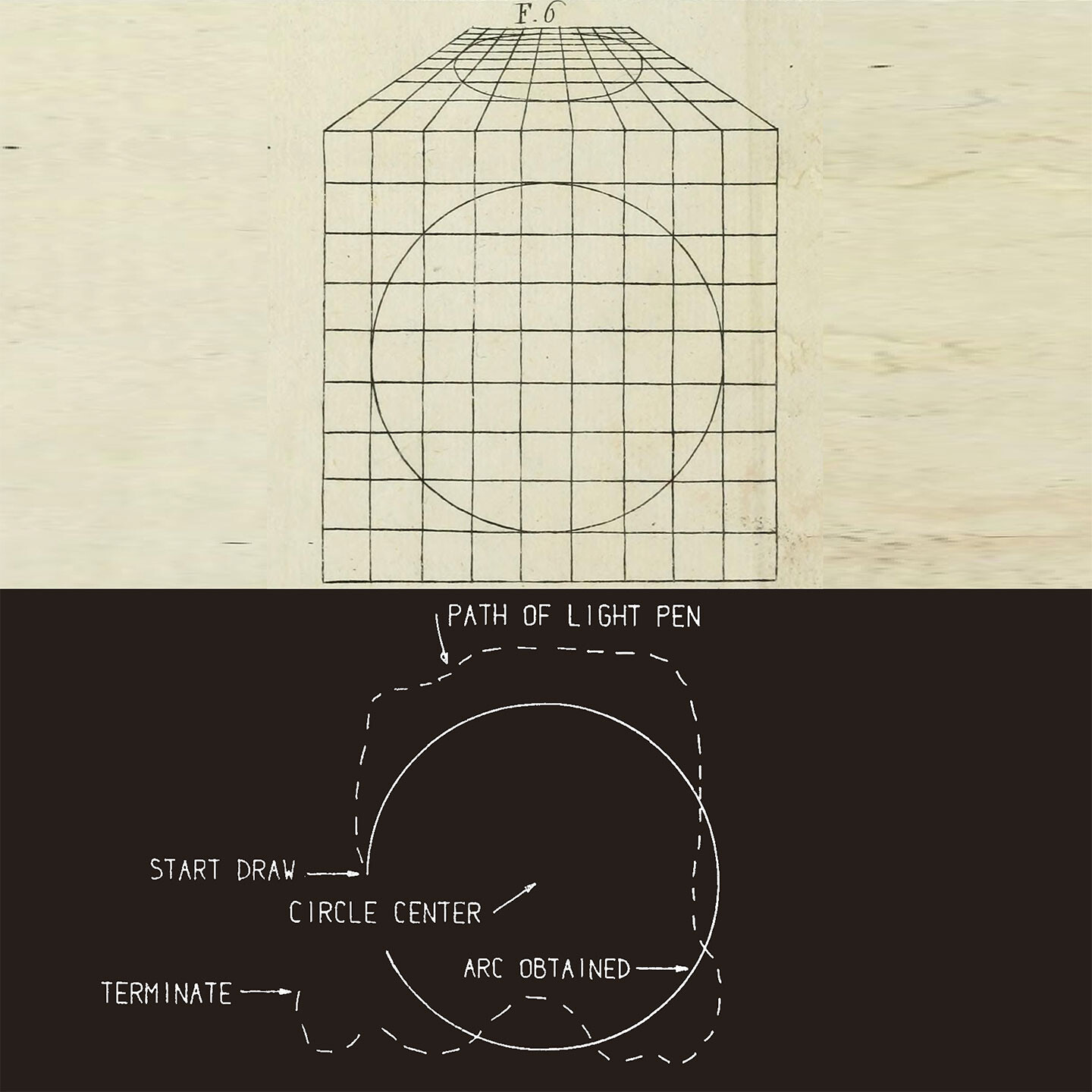

In 1986, during a flight over southwest Amazonia, the geographer Alceu Ranzi noticed a huge geometric earthwork cut through the middle of a vast tract of deforested land. From the ground, the structure was nearly imperceptible, as it mingled with the environment like a natural topographic feature, but from the vantage point of the aircraft, its precise architectural plan was clearly distinguishable as an engineered inscription on the surface of the earth. Ranzi recognized that the “geoglyph” was a pre-Colombian construction, and since then satellite-based surveys are showing that his striking finding is just one piece of a much larger archaeological complex formed by at least four hundred geoglyphs spread across a territory nearly the same size as the Netherlands. It is still uncertain whether this extensive network of monumental structures served military, religious or resource-management purposes, but through carbon dating it is possible to infer that they were occupied between the years 900 and 1500 of the current era, demonstrating that before the European colonial invasion this region of Amazonia was inhabited by Amerindian societies whose spatial designs produced remarkable transformations in the forest landscape.1

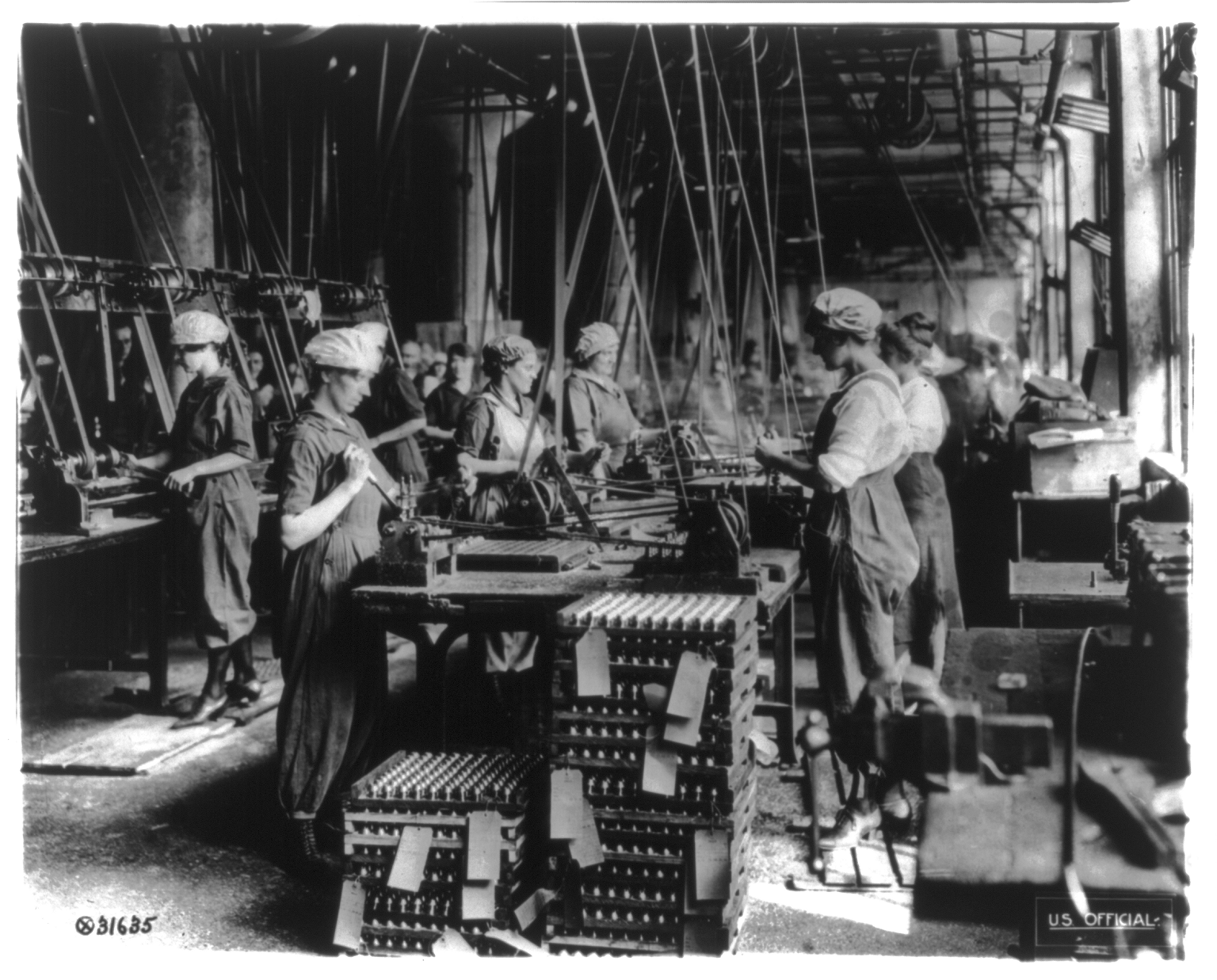

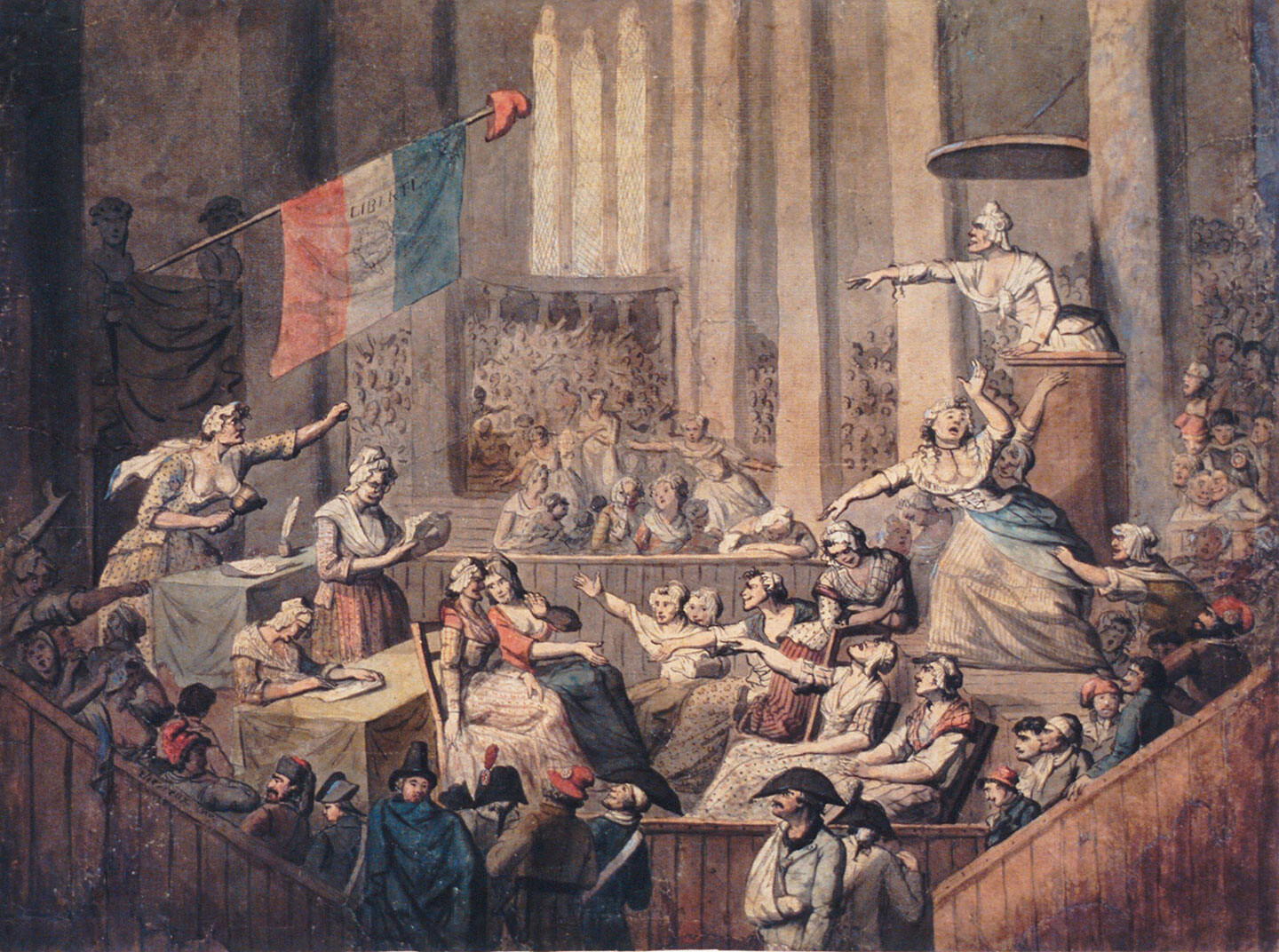

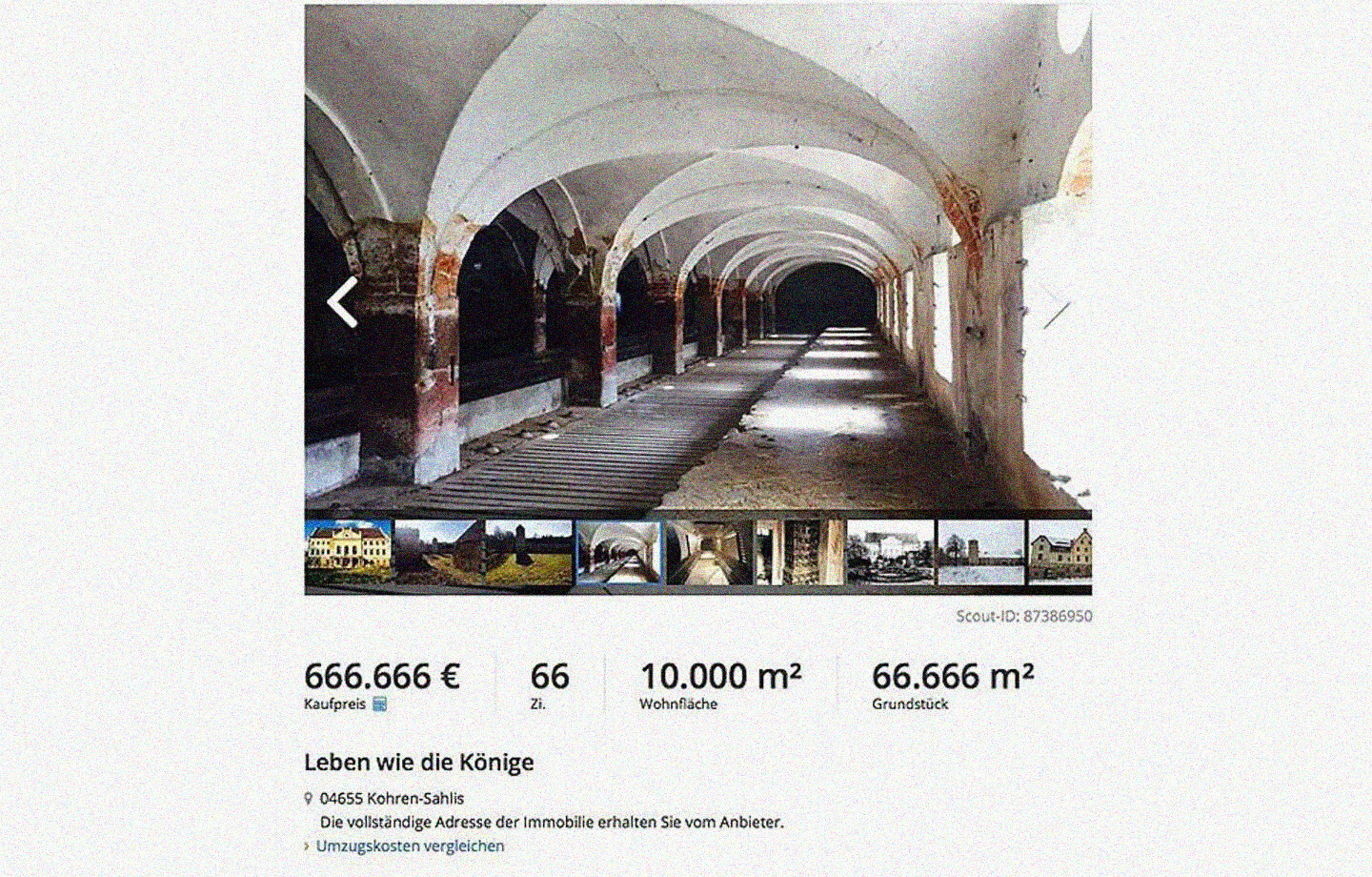

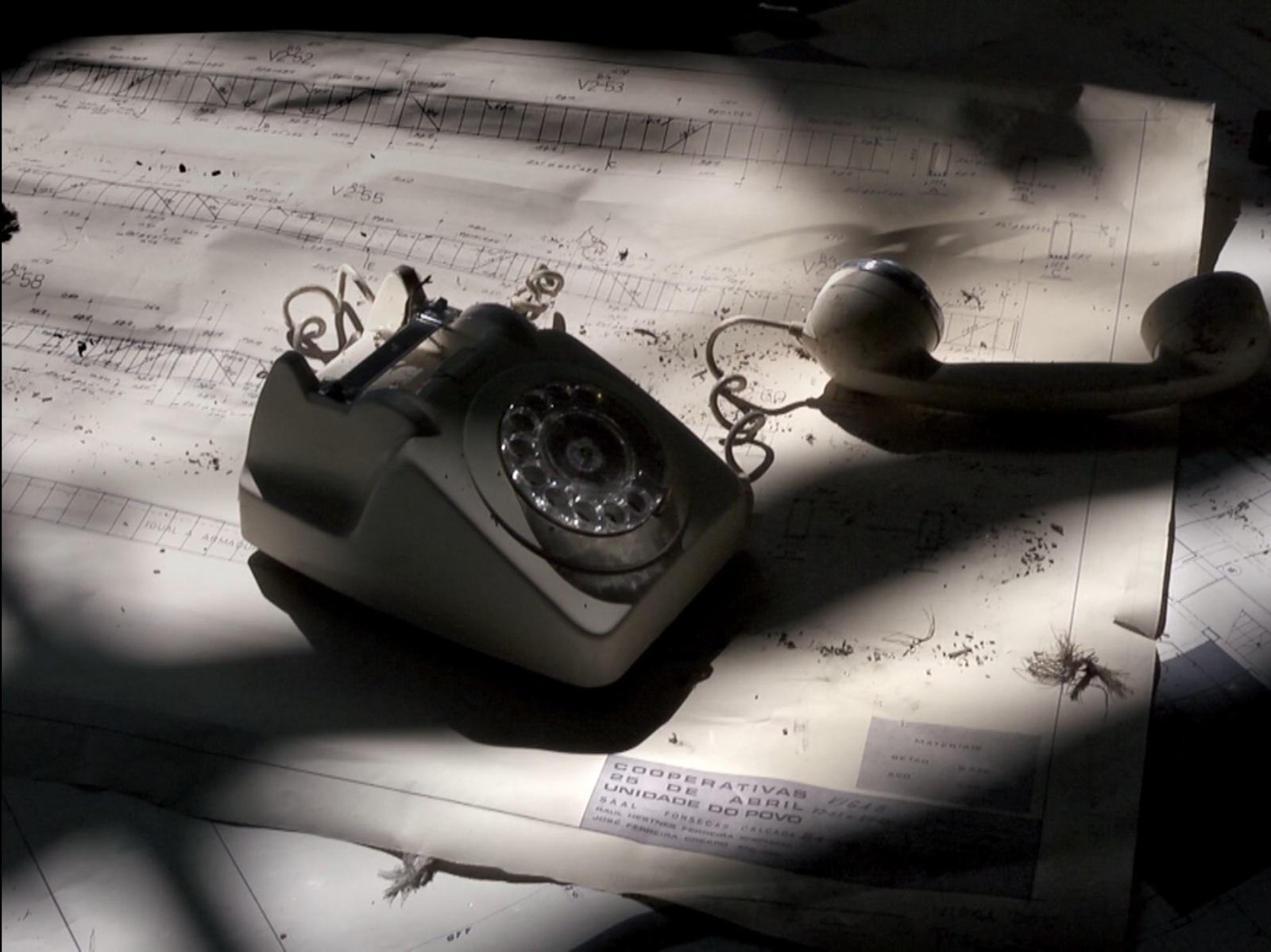

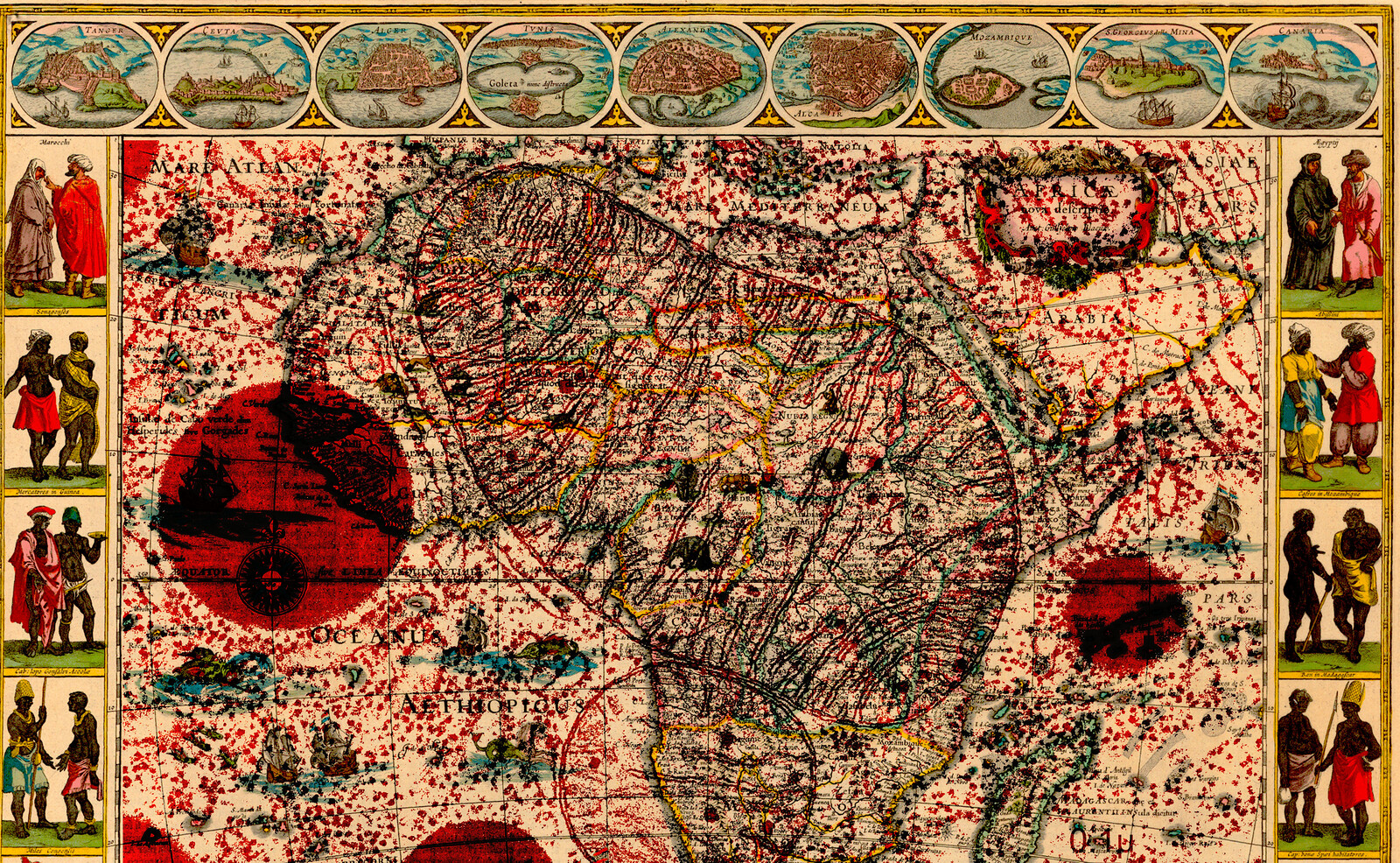

The geoglyphs remained unknown because after they were no longer occupied, the earthworks became covered by forest vegetation, and there probably exists hundreds more beneath the trees that still stand. In the 1970s and 1980s, when Brazil was ruled by a modernizing military dictatorship, this region was subjected to an aggressive project of colonization that unleashed rapid deforestation. This project was part of a macro-planning strategy to “occupy and integrate” the entire portion of the Amazon basin that fell within Brazilian sovereignty, nearly sixty percent of the total basin area. Its modern territorial schemes and spatial designs were based on the conception that the forest was an empty and homogenous terra nullius/tabula rasa that could be rationally domesticated, planned, and re-engineered as a whole. On the ground, the impacts of this militarized, masculine ideology of total control and exploitation of nature were extremely violent. Frontier modernization was accompanied by what the Brazilian Truth Commission described as a “politics of erasure” of indigenous peoples, which left on its wake thousands of disappeared persons, countless communities displaced, and caused severe, long-term and widespread damage to the forest ecosystem.2

The geoglyphs became visible in the middle of the devastated, savannah-like landscape inherited from the military dictatorship. Two monumental ruins of distant eras—the scorched lands of late modernity and pre-colonial earthworks—overlapping in space as complementary evidences of a continued, five hundred years-long genocide. More than historical documents of violence, the discovery of these structures shattered the colonial imaginary about the nature of the forest that animated frontier expansionism. Figurations of the pristine, wilderness, the “green desert” and many other images of de-humanized nature employed to describe the forest constituted other means by which the politics of erasure was perpetrated, displacing indigenous peoples and eliminating their histories in language as to veil the bodily violence of evictions, massacres and land grabs on the ground.3 This colonial imaginary had its complement and legitimation in scientific models that considered Amazonia to be a primeval environment that changed little since the Pleistocene, and over which native peoples exerted no meaningful impact. One of the central arguments supporting this view was the apparent lack of evidence that indigenous societies had domesticated and transformed their environs in any meaningful way, which was most clearly expressed by the conspicuous absence of archaeological complexes in the forest landscape. The lack of human design conformed to the pristine nature of the forest, inasmuch as the forest represented a negative image against which the concepts of both design and the human could be defined.

The Forest Against the City

The modern concept of design is directly associated with categories used to describe the environment in terms of dialectical oppositions, which in themselves contain relations of dominion, between domesticated and wild, cultivated and uncultivated, artificial and natural spaces. Forests—a term whose etymology in Romance languages, silva, is at the roots of the word savage—were particularly important in the historical process by which these cognitive schemes were crafted.

In the history of western ideas, forests most commonly represent a threshold against which the human condition is defined, figuring as the territory of humanity’s primeval state and its antithesis at the same time. This liminal aspect is related not only to the intimate association between the forest environment and the concept of wilderness, but foremost refers to the ways in which forests came to symbolize the outside, the negation, or the enemy of the space of the civic. The myth of the foundation of Rome tells that the city was built in a clearing carved in the dense silva: cutting and burning the trees was the first inscription of human design in the landscape. In its concrete form, the forest demarcated the legal-political boundary of Rome’s jurisdiction beyond which land was terra nullius, a lawless and unruly territory populated by barbarian tribes and all sorts of outcasts and outlaws. In the western imagination, the space of the social par excellence is the city, and the forest stands to the city in a relation of fundamental opposition.4

This image of the forest as a pre-civilizational space inspired modern theories of the social contract from Hobbes to Rousseau, and by the nineteenth century became entangled with orientalist geographies of colonialism and its attendant doctrines of social evolutionism and racial inferiority. Through the narratives of white explorers, colonial administrators, naturalists and ethnographers, the tropical forests of the colonial world were depicted as the Earth’s last pristine environments, isolated territories where society was found in its infancy and humans remained in a primitive, animal-like developmental stage. Amazonia, the world’s greatest tropical forest, was one of the most symbolic spaces through which this image of nature and society, and the structures of knowledge-power it sustained, was factored.

Amazonia was seen as a territory whose nature was as luxurious as it was inhospitable to civilization, which by virtue of its own environmental characteristics, imposed severe limits to the development of human societies. The north-American archaeologist Betty J. Meggers, whose pioneering work in Amazonia set the basis of this interpretation, attributed this limiting factor to cultural development to the incapacity of the tropical forest soil to sustain intense agriculture, which in turn hindered demographic growth, socio-political stratification, technological innovation and the consequent emergence of urban agglomerations. In Meggers’ model of environmental determinism, intensive agriculture was the “cradle of civilization,” and thus the predominance of the wild, undomesticated forest constituted the most meaningful evidence of the lower social evolutionary stage of Amazonian indigenous peoples.5

Since the 1980s, innovative work of a generation of archaeologists, botanists and anthropologists has been radically challenging this view.6 A series of new archaeological findings as impressive as the geoglyphs show that before European colonialism, great territorial expanses of the Amazon basin were occupied by populous and complex societies that employed advanced spatial technologies to produce large-scale modifications in the layout of the land. Moreover, the evidence shows that indigenous modes of inhabitation, both in the pre-colonial past and in the modern present, not only leave profound marks in the landscape but also play an essential role in shaping the forest ecology. Vast tracts of forests and savannahs in Amazonia that we perceive as natural are in fact cultural landscapes with a deep human past. The botanical structure and species composition of the Earth’s largest biodiversity refuge is to a great extent a heritage of indigenous design.

The Forest as the City

But what does it mean to say that Amazonia, a territory which so profoundly shaped the idea of pristine nature in our imaginaries and epistemic constructions, is an artifact of human designs? And, furthermore, that the planning technologies through which such a remarkable architecture came into being is well alive in the knowledge and spatial practices of contemporary indigenous societies? First, it means to finally abandon the still predominant socio-evolutionist interpretations inherited from the nineteenth century, to which the modern concept of design is largely tributary, that such practices are technologically primitive. But more important than asserting that the landscape architectures produced by Amerindian societies are as sophisticated as their modern counterparts, is to inquire into how they may open new venues for conceiving design altogether.

Rather than evidence of the lack of culture, we now know that the forest can be interpreted as a cultural artifact in itself, yet one whose contours do not fit within the binaries typical to western thought. Boundaries between domesticated-wild, cultivated-uncultivated or artificial-natural are not only never sharply demarcated in the landscape, but are practically meaningless to the modes by which the majority of indigenous societies perceive, engage with, and produce the forest. The Achuar, for example, like most indigenous groups of Amazonia, see the forest as an extension rather than the outside of the village space, and use the forest as a vast orchard which they codify in great detail.7 Ethno-botanic studies show that Kinja communities recognize nearly all trees and vine species in a given “wild” forest as directly useful,8 and the same is true for the Ka’apor, who employ a specific name—taper—to designate anthropogenic forests that grew over sites of ancient settlements, whose trees and plants they clearly distinguish as “archaeological” remnants of former villages inhabited by their ancestors.9

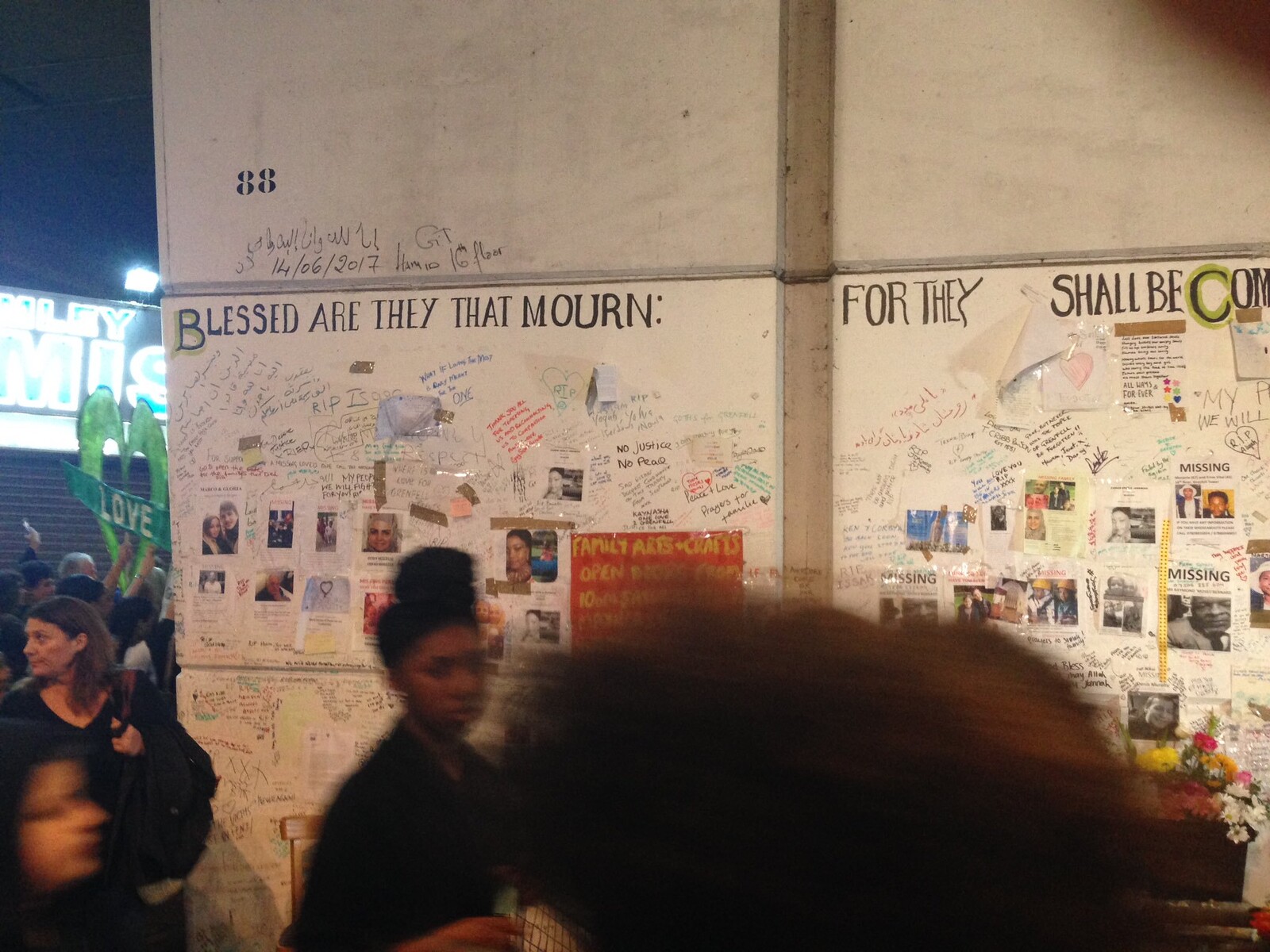

This apparent indifference to natural and cultural boundaries is also registered in the way the ruins of indigenous constructions appear as natural elements in the landscape, blurring figure and ground, while the natural environment itself—the content and distribution of plant species, the shape of the canopy, variations in topography and soil composition etc.—constitute archaeological records in their own right. Certain types of trees such as fire-resistant palms or highly fertile anthropic soils known as dark earths are among the most telling evidences of the constructed nature of the forest. Since they are part of the living structures of the forest, the nature of these ruins is completely different from the traditional idea of a ruin, to the extent that untrained eyes may hardly identify them in the forest landscape, let alone perceive the sophisticated infrastructures, landscape designs and urbanisms to which they bear witness.

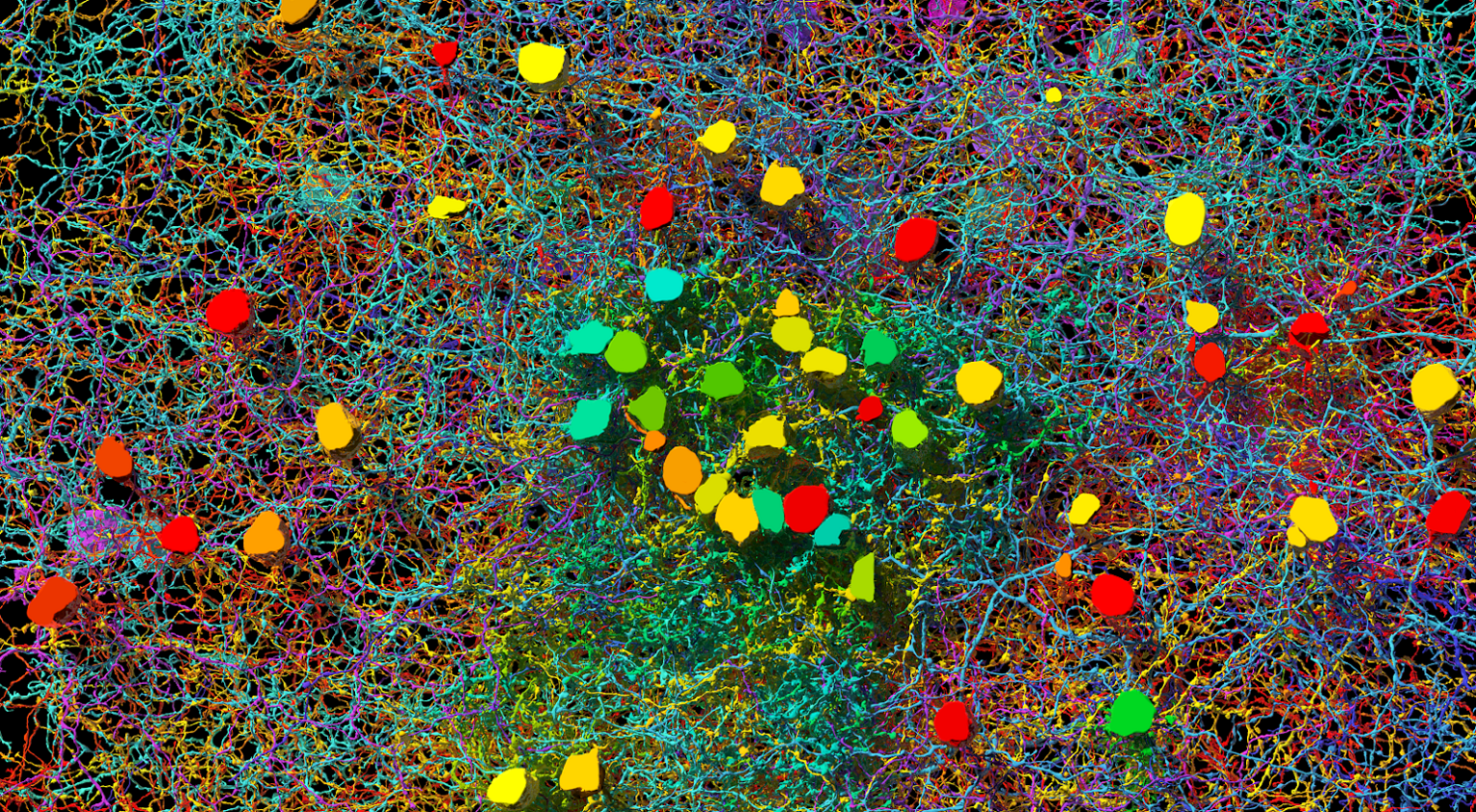

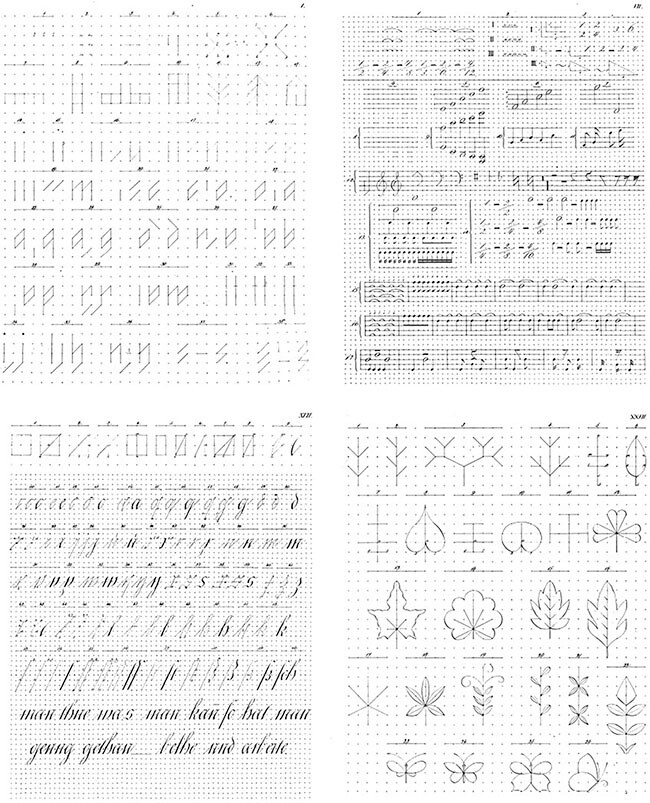

Analysis of anthropogenic disturbances in the forest fabric identifying sites of former settlements in the Kinja territory that were forcibly evicted during the “pacification” implementedby the Brazilian military dictatorship.

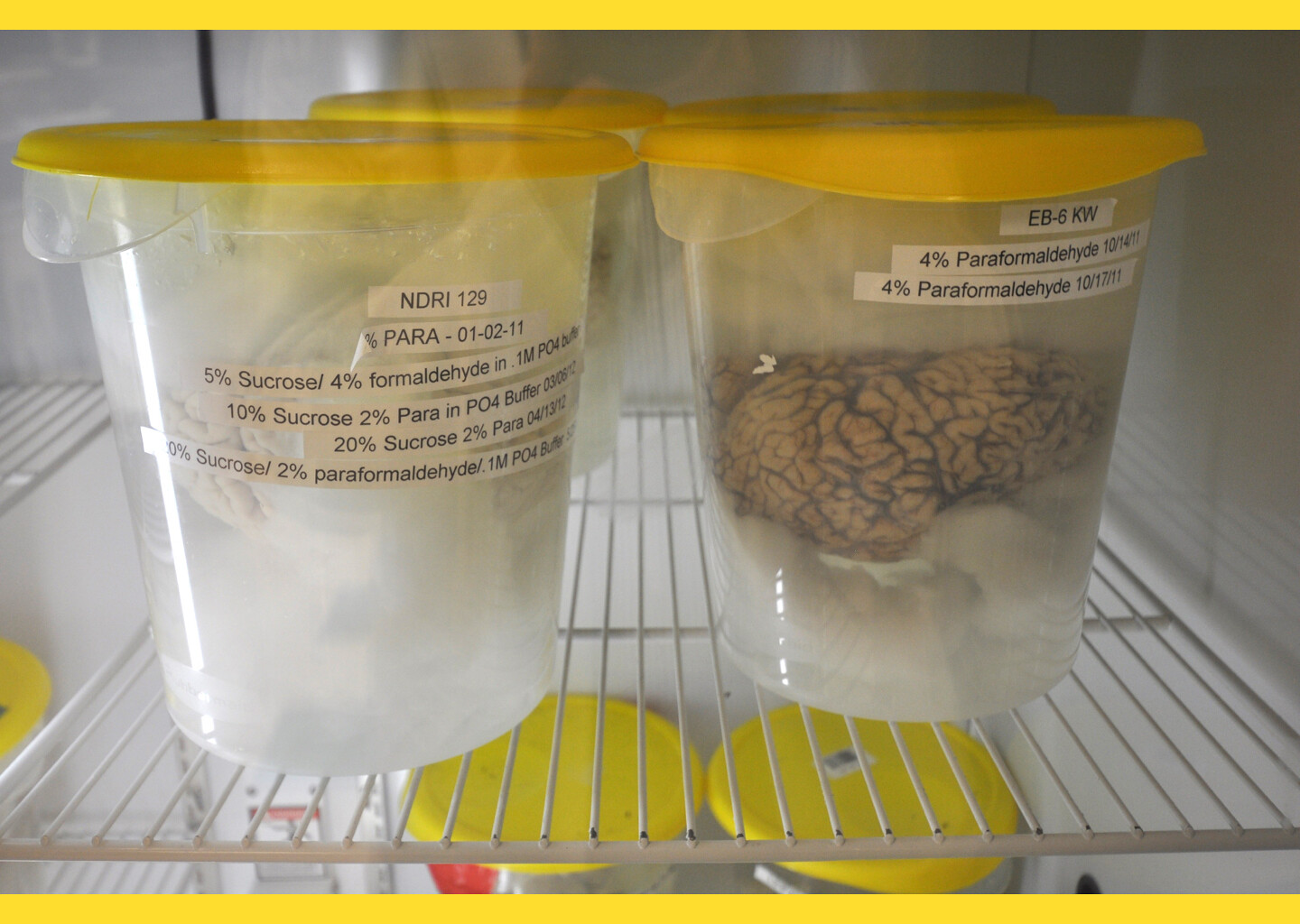

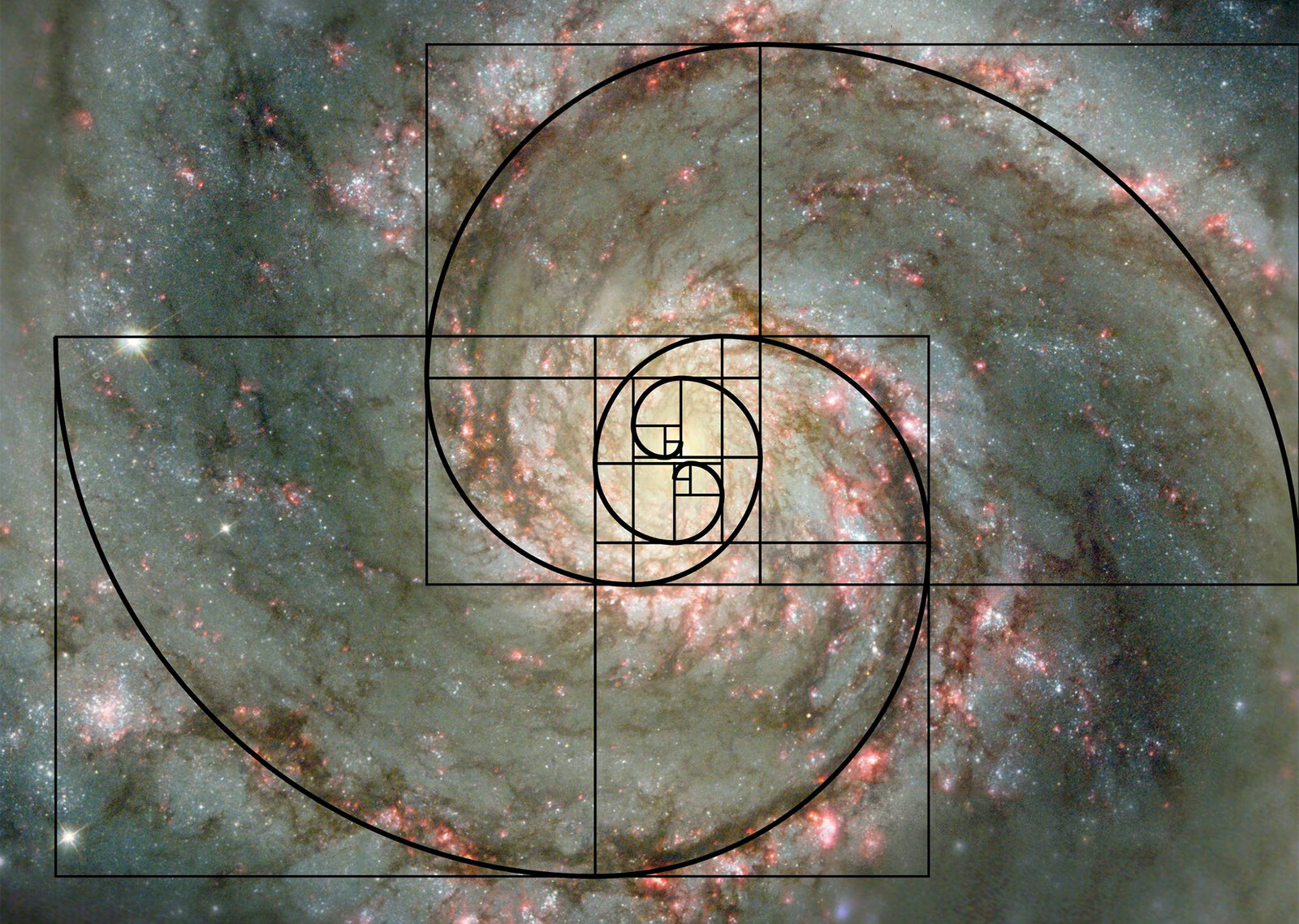

New evidentiary technologies—from remote sensing large-scale environmental transformations to the micro-forensic analysis of fossil seeds—are allowing to make visible the many different forms by which the forest, as ecologist William Balée writes, configures a great archaeological archive that “harbors inscriptions, stories and memories in the living vegetation itself.”10 In the same way we read the city as a historical text produced by social forces coded into material form—layers on top of layers of ruins forming a living social fabric—the forest stands to be interpreted through the syntax of spatial designs. Yet these living ruins are neither fully or exclusively human, nor are they completely natural. Rather, they are the product of long-term and complex interactions between human collectives, environmental forces and the agency of other species, themselves actors in the historical process of “designing the forest.”

Various indigenous societies not only recognize this constructed nature of the forest, but also extend the boundaries of this cultural milieu to the multitude of nonhuman beings housed by the forest. Amazonian peoples, like the majority of other non-western peoples around the globe, experience their relations with the environment and other beings as a continuum within which humans are elements of a vast social space that also include animals, plants and spirits. Therefore for the Makuna, “just like the indians, animals live in communities, in longhouses”;11 while the Kichwa of Sarayaku contend that the forest is populated by llaktas, “villages” or “towns” inhabited by all sorts of beings. As Débora Danowisky and Eduardo Viveiros de Castro write, what in western cultural imagination is called environment, the peoples of Amazonia consider “a society of societies, an international arena, a cosmopoliteia.”12 Such conception of the forest as a cosmopolis implies that every being that inhabits the forest—rivers, trees, jaguars, peoples—are “citizens”; agents or subjects within an enlarged political arena to whom even rights ought to be granted.13

The radical other that the forest presents is not a completely natural landscape, the absolute antithesis to the culturally saturated space of the urban, as in the mythology of Rome. Instead, it is an altogether different form of polis itself, one that escapes the spatial imaginaries, political geometries and epistemic frames of colonial modernity. Confronted with these other ruins, we may need to imagine a different myth of the foundation of the city as the space of the political, where the original design-act does not rest on clearing the forest but rather on the continued practice of its cultivation. This jurisdiction constitutes a political space beyond the limits of the city of western experience, a territory inhabited by all those human and nonhuman beings that live outside its walls, the outcasts and outlaws to the models of civilization, progress, and development to which the forest has always been the enemy.

Design Beyond the Human

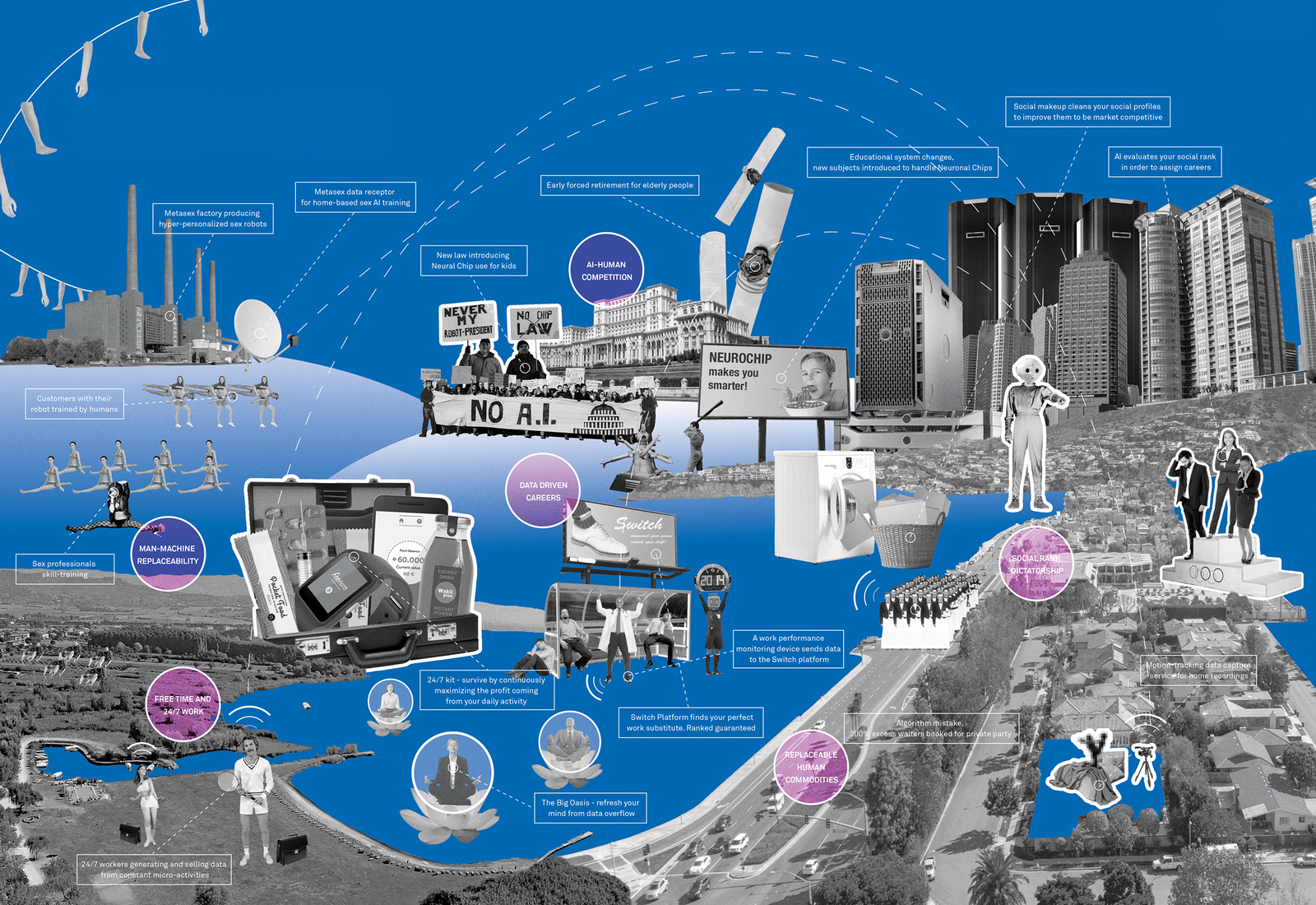

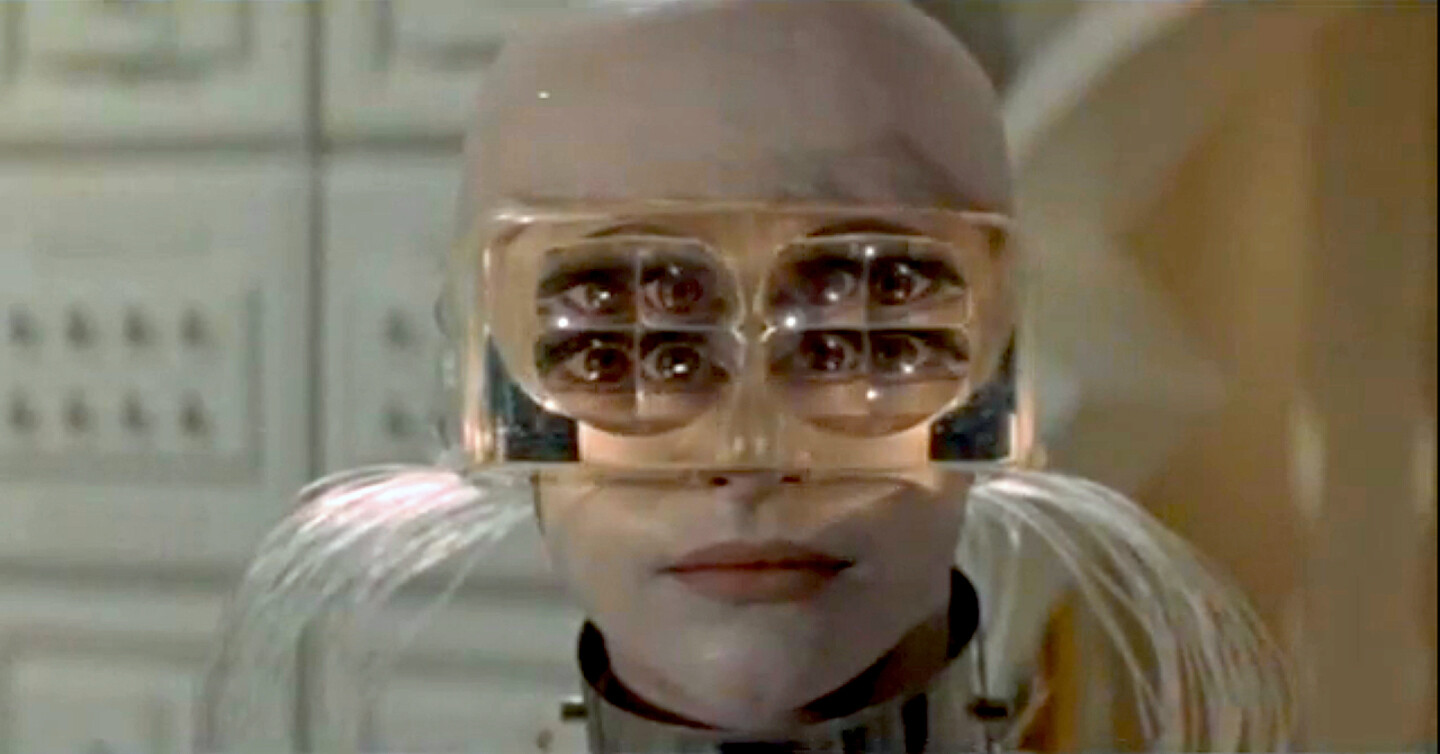

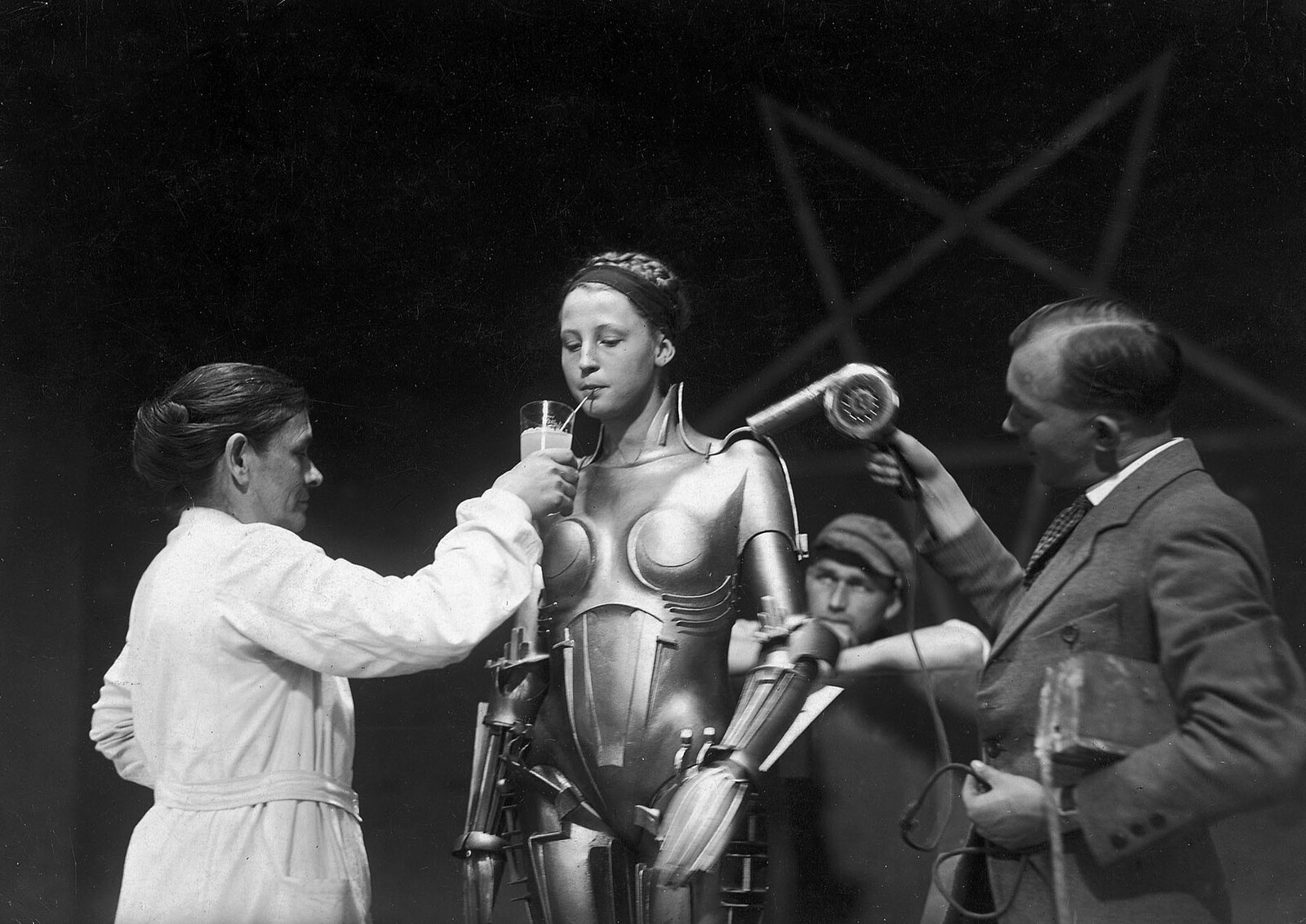

The modern meaning of design derives from the notion that design is a singular attribute that differentiates the human species from other beings, separating humans from nature by virtue of the unique power it confers to human subjects over the world. More than referring to the aesthetic or functional qualities of human-made objects, here the concept of design performs the function of an “ontological device” that delineates the realm of the exclusively human, since humans and only humans—by design—can impose instrumental control and symbolic meaning over nature due to their endowment with special qualities such as cognition, intent, and subjective will. As Karl Marx wrote in the nineteenth century, “a bee puts to shame many an architect in the construction of her cells, but what distinguishes the worst architect from the best of bees is this, that the architect raises his structure in imagination before he erects it in reality.”14

The ways by which we think the relationships between the concepts of design and the human still cling to this nineteenth century formula that man is homo designer, an autonomous calculating individual who can bend nature to his will. However, like Amazonian peoples but in a different way, contemporary science shows that the boundaries that separate humans from other beings are much more porous and unstable, for many of the attributes with which we try to distinguish ourselves as unique, such as reflective consciousness, intentionality, planning and language, are not limited to the human species. Ethologists teach us that various animals act with some degree of consciousness and planning, and that some species, particularly apes, manifest cultural behavior developed through language and the transmission of cognitive and technical skills, including the use of tools.15 Birds employ a form of sonic grammar; the communication systems of dolphins “exhibits all the design features present in the human spoken language;”16 and even bees are capable of transmiting knowledge and skills over generations.17 Some trends in ecological sciences consider trees in a forest as social beings, since they can learn, remember and exchange information through a living internet of funguses.18

Should we not also start considering that design is not the exclusive attribute of humans? Only if such an experiment would not follow the naïve idea that birds or jaguars or apes design their environments in the same manner as humans do, but rather enable us to forge a different image of design itself. When the anthropologist Eduardo Kohn, in his fascinating ethnography of the Runa people of western Amazonia, claims that “forests think,” he is not saying that forests think like humans, but offering a radically different possibility of thinking what thought can be.19 Beyond the human, we could draw a concept of design whose definition is not based on the act of a sovereign individual who imposes form over an inert and passive world of objects. But on a much more distributed, networked and collective process within which many forces and beings participate with varying degrees of agency in shaping and being shaped by the environments within which they coexist. After all, “wolves change rivers.”20

As design becomes such a widespread concept as to be rendered virtually meaningless, the way design is conceptualized has never been so politically consequential. The roots of the human-engineered ecological catastrophe towards which we are moving are deeply connected to the modes by which the relations between design, the human and nature have been conceived and operated in modernity. Anthropogenic global climate change make us realize that design is always the design of the Earth, of life itself, but there are different ways of articulating the novelty this represents. The concept of the Anthropocene is so hype in the field of design because it denotes that the whole planet, in the totality of its geophysical processes, has turned into design’s ultimate object of mastery. The living ruins of Amazonia tell a different, dissident story, suggesting an image of design that is less about planning and more about planting the planet, inasmuch as planting is also a practice of planning and design, but one that needs to be fine-tuned to the agency of winds, climates and the myriad of beings upon which the seeding and pollination of life depends. Beings as vital to humans as bees, and at a moment in which the ecocidal designs of late modernity are driving bees to extinction, let be the bees, and not man, draw the concept of design with which we can make life a possible project amidst the ruins of the “age of humans.”

Martti Pärssinen, Denise Schaan, and Alceu Ranzi, “Pre-Columbian Geometric Earthworks in the Upper Purus: A Complex Society in Western Amazonia,” Antiquity 83 (2009): 1084–1095.

Comissão Nacional da Verdade (CNV), Final Report, Volume II: Tematic Texts (December 2014).

A common practice used in the period of the military dictatorship was the emission of “negative certificates” to attest the inexistence of indigenous peoples in areas they traditionally inhabited and from which they had been evicted to open space for development projects.

Robert Pogue Harrison, Forests: the shadow of civilization (Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, 1992).

Betty J. Meggers, Environmental Limitation on the Development of Culture, in: American Anthropologist, New Series, Vol. 56, No. 5, Part I (Oct, 1954).

My engagement with archaeology in Amazonia is informed by reading, interviewing, and talking with many protagonists of this generation, including Eduardo Neves, Michel Heckenberger, William Balée, and Stephen Rostain, to whom I am most grateful. Particularly important were the works of Heckenberger, The Ecology of Power (New York: Routledge, 2005); Balée, The Cultural Forests of Amazonia (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2013); and Eduardo Neves, Sob os tempos do equinócio: oito mil anos de história na Amazônia (Doctoral Thesis, Museum of Archeaology and Ethnology, University of Sao Paolo, 2012).

Philippe Descola, In the society of nature: a native ecology in Amazonia (Cambridge University Press, 1994).

William Miliken et all, Ethnobotany of the Waimiri Atroari Indians of Brazil, (Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, 1992).

Ibid., Balée.

Ibid., Balée.

Philippe Descola, Beyond nature and culture (Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, 2013).

Déborah Danowski and Eduardo Viveiros de Castro, “Is there any world to come?” e-flux →.

By the influence of Maori peoples activism, New Zealand courts recognized forestlands and rivers as legal persons. See Bryant Rousseau, “In New Zealand, Lands and Rivers can be people,” New York Times, (July 13, 2016) →; in Bolivia and Ecuador, countries where indigenous movements play an important role in national politics, the constitutional law considers nature as a subject of rights.

Karl Marx, “The Labour-Process and the Process of Producing Surplus-Value,” in Capital: A Critique of Political Economy, Volume 1 (London and New York: Penguin Books, 1990).

Ape Culture, eds. Anselm Franke and Hila Peleg (Leipzig: Spector Books, 2015).

Sarah Knapton, “Dolphins recorded having a conversation ‘just like two people’ for first time,” The Telegraph (11 Sept. 2016) →.

Kate Kelland, “Brainy Bees learn how to pull strings to get what they want,” Reuters (4 October 2016) →.

Sally McGrane, “German Forest Ranger Finds That Trees Have Social Networks, Too,” New York Times (Jan 2016) →.

Eduardo Kohn, How forests think: toward an anthropology beyond the human, (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2013).

“How Wolves Change Rivers,” Youtube →.

Superhumanity is a project by e-flux Architecture at the 3rd Istanbul Design Biennial, produced in cooperation with the Istanbul Design Biennial, the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea, the Govett-Brewster Art Gallery, New Zealand, and the Ernst Schering Foundation.

Subject

Superhumanity, a project by e-flux Architecture at the 3rd Istanbul Design Biennial, is produced in cooperation with the Istanbul Design Biennial, the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea, the Govett-Brewster Art Gallery, New Zealand, and the Ernst Schering Foundation.