The 1990s were dominated by debates about postmodernism, one strand of which was concerned with the so called “aestheticization of the life world.” Wolfgang Welsch, for example, wrote in Grenzgänge der Ästhetik, “The facades get prettier, the shops more animated, the noses more perfect. But such aestheticization reaches deeper, it affects fundamental structures of reality as such.”1 For aestheticization means “basically that the non-aesthetic is made aesthetic or is grasped as being aesthetic.”2 However what counts as aestheticization and which concept of the aesthetic is presupposed can vary, as he goes on to explain:

In the context of an urban environment, aestheticization is referring to the expansion of the beautiful, the pretty, and the stylish; in advertisement as well as in self understandings it means the growing importance of performance and life style; in view of the technological determination of the objective world and the social effects of the media, “aesthetic” primarily designates virtualization. Finally, aestheticization of consciousness means: We no longer see first or last foundations, instead reality takes on a condition we formerly only knew with respect to art—a condition of being produced, changeable, non-committal, levitating etc.3

Whereas Welsch, from the perspective of a somewhat generalized constructivism, affirmed these developments as a move towards the freedom of designing ever more spheres of life,4 others were more skeptical. Not only did they doubt that postmodern urban space should indeed be characterized by an “expansion of the beautiful and the pretty,” they also saw in the postmodern emphasis of the surface a symptom of an ugly social truth: that of a profound alienation. In their view, the postmodern cult of the surface was a symptom of a novel domination of simulacra that erodes the substance both of our ethical self understandings and our political culture. “Reality,” Rüdiger Bubner wrote, “gives up its ontological dignity in favor of an applauded semblance.”5 Both sides of the debate, however, assumed that aestheticization is not just a question of design, but that this question itself should be seen in a broader social context. “Aestheticization of the life-world” is thus a formulation with which both sides tried to find a tangible concept for the state of contemporary Western societies.

However, the agitated argument over the status of a supposedly obvious societal development that dominated the 1990s was soon to be deflated by sociology, for the philosophical debate remained unfounded as long as it was possible to question the actual scope of this development.6 As a result, attempts to empirically substantiate the thesis of the aestheticization of the life-world quickly came in for criticism, such as Gerhard Schulze’s thesis of an “experience society” brought about by affluence,7 who was in turn accused of falsely generalizing a phenomenon located in the more privileged part of society.8 Today, the parameters of this debate seem to have shifted: A much more prominent role is played by studies which show that aesthetic motifs such as creativity, spontaneity and originality are no longer signs of a sphere of freedom lying beyond the necessities of social reproduction, but have themselves become an important productive force in the capitalist economic system. According to this research, these motifs have turned into crucial social demands, representing an increase of constraints rather than freedom.9 In any case, sociology seems to have become the central location for serious debate on how to appropriately describe, explain and evaluate the crucial position of aesthetically connoted criteria both for individuals and for the organization of society in Western democracies.

But as relevant as these debates are, I believe that philosophy has been wrong to retreat from them. After all, the diagnosis of aestheticization implies an assumption about the undistorted essence of both ethics and politics, which is not merely an empirical, but systematic question. The specific approach of philosophy in the context of contemporary diagnoses, however, can only become fully visible once we turn away from the business of diagnosing the present and turn to the history of philosophy. Contrary to the impression raised by recent debates, aestheticization in no way represents simply a contemporary problem; and traditionally, the concept is much more philosophical than is suggested by the largely sociological character of the current discourse. In fact, philosophical discussion of the challenges posed by certain aesthetic motifs for understanding ethics and politics even goes back to antiquity. The history of practical philosophy can even be seen as a history of crisis-diagnoses that have sought to combat the invasion of the aesthetic and its disintegrating effects into the spheres of ethics and politics. Without a reflection on the long history of this discourse the claim that the “aestheticization of the life-world” represents a new phenomenon and a new epoch will remain questionable. Without a detailed discussion of the problems that practical philosophy has historically ascribed to “the aesthetic,” our judgment of current developments will be in danger of either merely carrying over old prejudices into the present, e.g. by criticizing a supposedly novel domination of simulacra, or we will end up becoming a part of an old problem rather than a part of the solution, e.g. by becoming proponents of a supposedly new, constructivist relation to ourselves and the world. In order to clarify the philosophical assumptions that at least indirectly influence these debates, we require a historical and systematic discussion of the history of the philosophical critique of aestheticization.

As I have already indicated, this history begins in antiquity, or more precisely, with Plato’s critique of democratic culture in The Republic. Plato mistrusts the “colorful” plurality of life-forms in a democracy, as well as the “dazzling” democrats that have learned from (theatre) poets that it is possible to adopt several roles in life. He even sees a major problem in the pretty appearance of democratic culture and its privileged life-form. For according to Plato’s diagnosis, the logic of appearances constitutes the essence of democracy itself: The ethical commitment to the good gets replaced by an aesthetic stylization of existence, while good government (i.e. government that is committed to the good) gets replaced by an uncontrolled spectacle that seduces the people. For Plato, this logic is a small, dangerously subtle step on the path from democracy to tyranny. What is astounding about this diagnosis from antiquity is how familiar its central motifs are even today. Indeed, these motifs were picked up again in the philosophical discourse at the beginning of modernity (around 1800) and have continued to play an important role into the twentieth century and beyond. But why does Plato, of all thinkers, prove to be such a decisive source when it comes to naming the problems of modern democracy, or rather the problems associated with its aestheticized culture? After all, the model of democracy in antiquity cannot be applied to modern democracies; just as little can the arts of antiquity, which Plato criticized for their subversive influence on morals, be equated with modern art-forms. Nevertheless, it is no accident that modern philosophical thought on the matter draws on the work of Plato.

Plato invented a type of critique that has become so crucial for modernity that, despite the obvious differences between antiquity and modernity, a good deal of conceptual effort has been undertaken to revive it. Plato connects his analysis of various forms of government with his investigation of—to put it in modern terms—forms of subjectivization. The connection between government and self-government takes on greater significance in modernity, despite the fact that the organization of the state is no longer regarded as mirroring that of the soul, as is suggested at several points in The Republic. However, if we take a closer look at Plato’s account of this connection, we find the more complex argument that government and self-government are not merely similar to each other, but rather that they form an analogous unity via their respective relation to a value that is central to both, which in the case of democratic culture, is freedom. This thesis on the relationship between ethics and politics is what has remained crucial to the modern critique of aestheticization, and the key to the modern debate on aestheticization is likewise the problem of freedom. If the diagnosis of aestheticization sometimes more, sometimes less explicitly refers to democratic culture, then the freedom that defines this culture is the systematic problem with which it is both ethically and politically concerned.

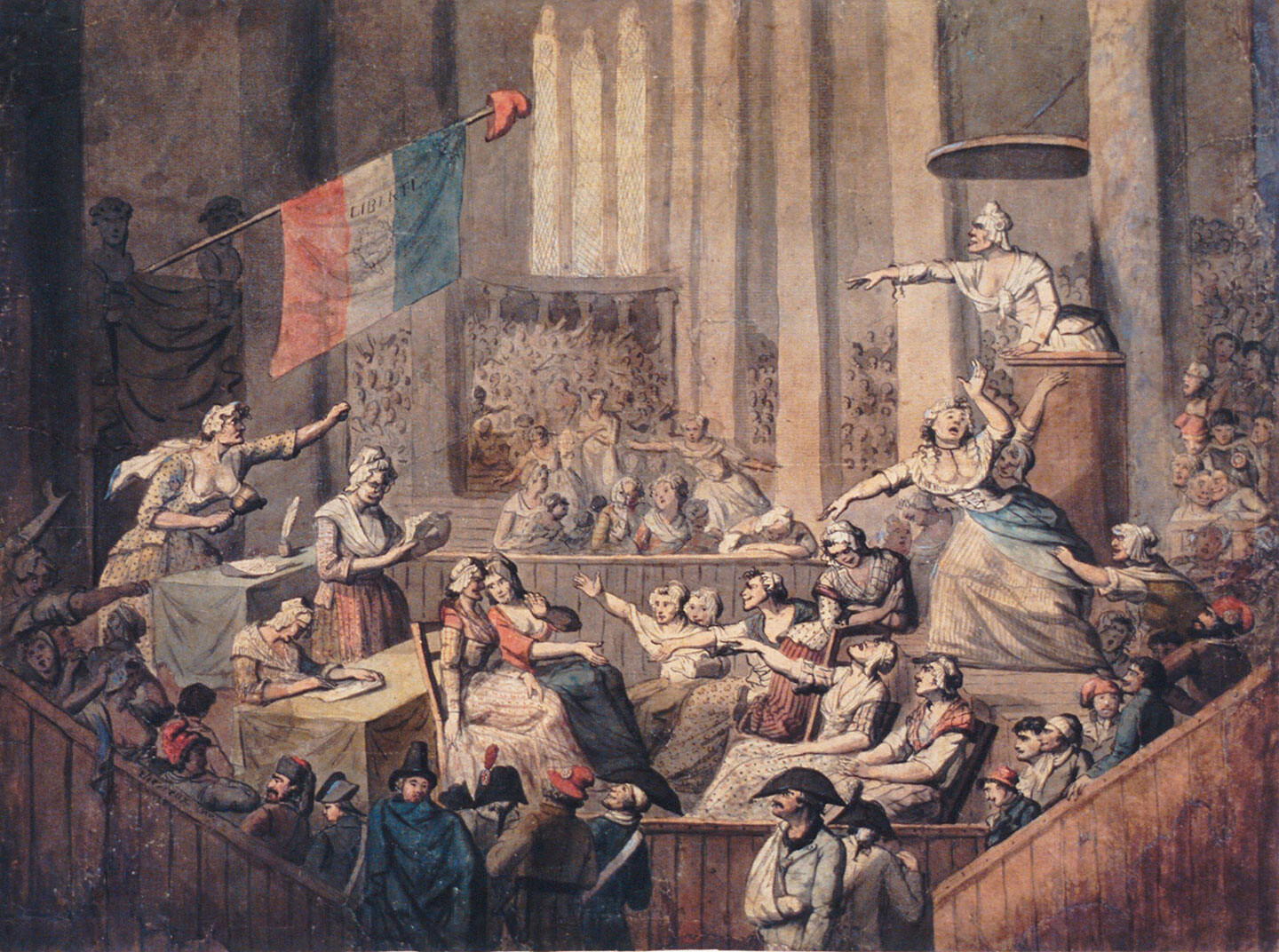

More precisely, what is at stake is a concept of freedom associated with aesthetic motifs, namely a form of freedom that contradicts social practices, their normative orders and the corresponding identities or roles. It does so by giving private motives (moods, pleasure, taste) such a clear priority over conformity to a given social order that they come to dominate the way that individuals determine their own lives. Critics of aestheticization fear that such a private model of freedom, if successful in establishing itself in society, will have a disintegrating effect on the political community. At best, social bonds will be replaced by “aesthetic” relations; and where there are no longer any social bonds, the staging of community becomes a politically decisive force. Yet the staging of community, as critics of aestheticization go on to argue, does not create community. On the contrary, not only does it barely conceal the fact that it is only necessary because the collective has been undermined from within by the aesthetic self-understandings of its (non-)members, but it is only capable of producing a community to the degree that it simultaneously establishes a divide between those that produce the community and those who—again in the form of moods, pleasure and taste—receive it. The political community thus disintegrates into a spectacle and an audience.

Because of its disintegrating effects, the aesthetic form of freedom has been denounced as a “degenerate freedom” by Plato or as “caprice” or “arbitrariness” (Willkürfreiheit) by Hegel. In the history of the philosophical critique of aestheticization very different conceptual presuppositions have been employed in order to deliver proof, and it is here that the gap between modernity and antiquity becomes particularly visible. However, since Hegel’s objection to the romantic ironist, this critique has taken the shape of a reference to the constitutive role of social practices for the unfolding of individual freedom. Without question, this reference is still justified today. It captures extreme constructivist positions that reduce the possibility for shaping one’s own life to a question of individual ethics,10 as well as all those who argue that Foucault’s demand “not to be governed like that” refers to the entirety of life—just as if a life beyond all social determination were desirable or even possible.11 Not only is everybody always involved in social practices, but any understanding of the self requires social recognition in order to be realized.12

But by exclusively associating “aesthetic” freedom with freedom from the social in toto, the critique of aestheticization conceals another, more productive interpretation: Distance from the social does not necessarily entail a distance from all social determinacy—a distance that would be as abstract as indeed imaginary. We could also grasp this distance in a different way: not as a model for the life of the subject, but as a productive element of it. Referring to aesthetic existence, to “dazzling” life-forms, does not mean demonstrating and defending abstract freedom from the social, but rather the mutability of the social itself. The aestheticization of freedom would then no longer stand for the misunderstanding of a kind of freedom from the social, in a kind of non-dialectic opposition, to freedom in the social. Rather, it would express the tension at the heart of the life of every individual. Changes of the self are not brought about by a pseudo-superior subject standing above all social identity. Instead, such changes are rooted in experiences of self-difference, which compel the subject to reconceive of itself, its self-understanding, and the meaning of its subjectivity from a distance. I do not distance myself from an overly disciplined self-understanding, for example, by placing myself over this understanding—as if I were the sovereign of my own sovereignty—but, to the contrary, by experiencing desires that counter them in such a way that I (by laughing about myself) become free for new, probably more appropriate self-images. Whoever lives within the misunderstanding of solipsistic self-production is thus just as unfree as those who have never had the experience of distance from themselves, their social roles and its corresponding expectations. It is only possible to mediate between both sides of this tense relationship if we grasp them as elements in a process in which we can change both ourselves and the social practices of which we are a part.13 Indeed we would misunderstand the changes in ourselves if we took them to be merely private changes. Through these changes we change the practices of which we too are a part. Occasionally this can occur without our noticing, while in other cases it can lead to collisions between ourselves and existing practices, a collision that can only be removed by making explicit changes to either ourselves or the world. That I now choose to understand myself differently can also mean that in order to be able to live out my new self-understanding I must enter into a struggle for recognition.

To defend the possibility of such change, however, means to defend the possibility of changing given determinations of the good as a good in itself. The form of government that has integrated the possibility of questioning given determinations of the good into the concept of the good itself is—as Plato already clearly recognized—democracy. It is the only form of government in which it is allowed to publicly criticize everything, to publicly call everything into question—including the shape of democracy itself. Because it remains open, despite all the risk involved, to re-determinations of the good, and thus to the possibility of a more just order, democracy remains—to cite the now famous formulation employed by Jacques Derrida—“to come.”14 Yet this is not meant, as Derrida is often misunderstood, as an eternal suspension until the arrival of a coming messiah of democracy. On the contrary, our determinations of the good are all that we have for realizing our freedom in the here and now. Democratic openness to future events neither means openness for the sake of openness, nor is this a fundamental criticism of normative determinations in general. Rather, it emphasizes the possibility of historical revision. For precisely this reason, democracy, to cite Claude Lefort, is the “historical society par excellence.”15 Yet due to its insight into the historicity of the good, democracy indeed has an internal connection to what has been criticized as the “aestheticization of the political.” We can make plausible that participants in social practices are always potential non-participants, and thus also that members of society are potential non-members, such that the meaning of social practices can be called into question at any time. If this is the case, then the immediate result will be a critique of pre-political conceptions of the order and unity of the political collective. Neither the order nor the unity of the community can simply be presupposed; rather its character is revealed to be a political determination. Furthermore, this means that the unity of the community, along with the order within which it is grasped, must be politically created, produced, staged. Because democracy knows neither order nor unity beyond political representation, it not only stands in clear opposition to Plato’s anti-democratic conception of the natural political order, but also concerns the idea of collective self-government, an idea that is central to the modern understanding of democracy. This latter point has far-reaching consequences, for if it is true that the self of collective self-government cannot be assumed to be a unified will and that it must first be brought forth by political representation, then this means that the demos of democracy can never exist beyond the separation thereby established between representatives and the represented, producers and receivers, the rulers and the ruled, performers and the audience. The demos can therefore never exist outside of relations of power and domination; it never exists as such. In fact, sovereign power and authority are presumed the moment someone steps forward and claims to speak for everyone, yet the people being spoken for are helpless against this presumption of power only to the extent that they are blinded by measures designed to conceal the elements of sovereignty and rhetoric entailed by this act. The democratic answer to the problem of sovereign power does not consist in concealing the latter, but in exhibiting it and thus exposing it to an examination of its legitimacy. For it is precisely through this democratically understood “aestheticization of the political” that democracy preserves its openness to the future. On the democratic political stage, the representatives of the demos must justify themselves before those whose will they represent; they must face a heterogeneous audience whose members always potentially have or develop alternative conceptions of the democratic general will, which can ultimately be asserted publicly as a (counter) power in opposition to the currently prevailing conception.16

Such a defense of an aesthetic, even theatrical dimension of democracy, of the necessity of representation (and the sovereignty that comes with it) does not mark the end of a critique of representation but its beginning. Contrary to the generalized critique of all forms of political stagings or “the media,” we now need a critique in the original sense of the term, i.e. as differentiation. First of all, we must distinguish the aesthetic of totalitarian stagings of unity and of post-democratic disintegration from the political stagings in which democratic power justifies itself before the demos that it claims to represent. Within the framework of totalitarian mass spectacles, for example, everything serves the ideological expression of unity. However, the realization of such a totality, which excludes any kind of division, can only be had at an extraordinarily high price. To the degree that power succumbs to the “madness,” as Claude Lefort and Marcel Gauchet write, of embodying the position of universality and articulating the true general will, power necessarily passes over into the particular: “Instead of the universality to which it lays claim, we only perceive the arbitrariness of rules and decisions, the narrow bias of judgment and the constant resort to brute force”.17 The contradiction of totalitarianism consists of the fact that “the sought-for elimination of all divisions within society requires a power that separates itself from this society and thereby divides itself between the claim of its transcendence and its factual social immanence.”18 The fact that totalitarian rule is “doomed” in spite of “all the compulsory measures at its disposal” does not eliminate the possibility that the totalitarian vision can succeed in reality—even if only for a certain time, which history has shown to be necessarily too long.19

Italian police officers covered in pink paint by students protesting a school reform plan in Milan, Italy, March 12, 2015.

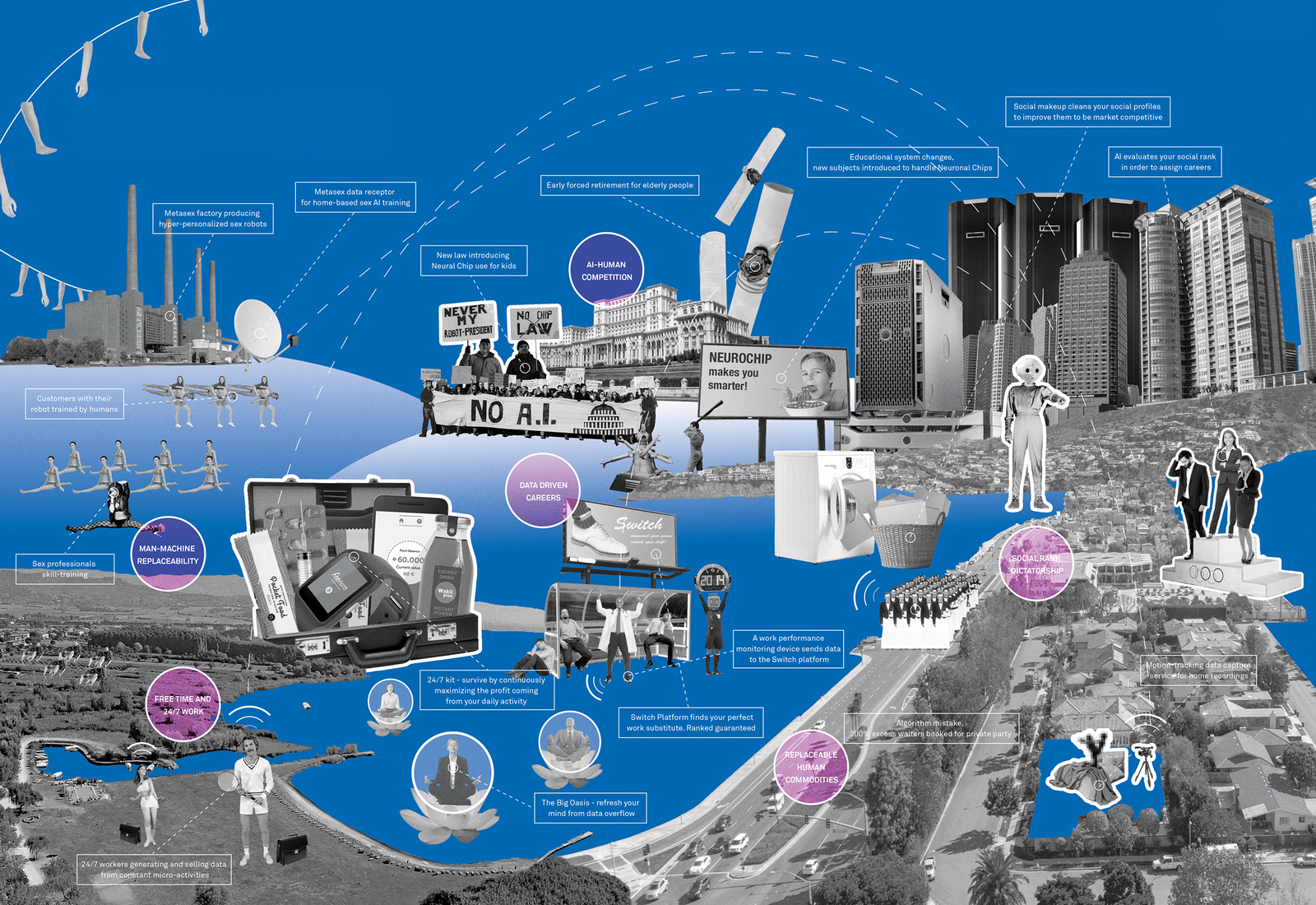

In its own way, post-democracy, too, is determined, like totalitarianism, by the ideological conception of a complete accordance of power and society.20 Only this time the idea of accordance is accompanied by a visual culture that is not shaped by an aesthetic of unity, but by an aesthetic of disintegration; it is precisely the endless openness of this culture which proves to be especially inclusive. Post-democratic power denies itself up to a point at which it negates its own sovereignty to define the common good and instead merely claims to manage economic necessities and constraints.21 To the degree that power legitimates its actions by invoking its own powerlessness, the responsibility for the state of society and the situation of each individual is pushed onto the governed (and no longer onto the government), thereby equating itself with the image of a (neoliberal) classless society that embraces even the poorest of the poor by according them the potential for creative self-realization. Each individual should see himself “as his own militant,” 22 as a bundle of energy that can be molded to fit into continuously new contexts with new contracts, all the while viewing themselves as being in pursuit of their own pleasures. You just have to want it. In terms of a politics of representation this corresponds to a “regime of the all-visible” which eliminates the distinction between image and reality; all citizens are granted the opportunity to present themselves and their individual particularity, but they are no longer met with the expectation of a demand for political representation. By granting each person the possibility of individual visibility, post-democracy claims that it has given each person his or her just due. In both aesthetic and political terms, this recalls the nightmare of a society that has taken on the form of an afternoon talk show.

Both extremes demonstrate the urgency to not only defend a democratic setting in which power appears and must legitimize itself as such, but also the many stages on which arguments about the appropriate representation of the demos, about the respective version of the general will, can be carried out. These are the different, partially interlocking dimensions of democratic life on which the self-difference of the demos can occur: it not only appears in the relation between the government and the non-parliamentary opposition, but also in the relation between the government and the parliamentary opposition; between politics and the media; between the media and the citizens; and finally, between citizen and man, the limit of democratic community. Those cases in which one or more of these differences are absorbed or ignored should appear to be a problem, such as whenever human rights are equated with the civil rights granted by nation-states, or when the relationship between the government and the opposition is eliminated in favor of a one-party state; when free speech and the right to protest are restricted, or when the influence of economic and/or political power blurs the line between politics and the media. Within this perspective, discussions about different formats and strategies of political communications, or the role of new technologies and media for the formation of publics and counter-publics, gain critical relevance.

Defending the levels of democratic life that bear witness to a conflict over various views of what is publicly relevant, of what constitutes the common will, means abandoning the conception of democracy as the final, good form of rule in which the problem of sovereignty has been overcome, just because “the people” itself takes up the position of the sovereign, for this conception presupposes the problematic fiction of an identity of the demos with itself. Given the unforeseeable heterogeneity of its (non-)members, this notion of democracy is a structurally totalitarian one. The insight that the demos never exists outside its representation implies, as we have seen, the recognition of an element of sovereignty at the very foundation of democratic societies. However, this is not the unfortunate death, but the beginning of democratic politics. For this is the kind of politics whose dynamic derives from the experience of the self-difference of the demos, in which democracy is realized only by means of a constant struggle over the nature of its very concept.

Wolfgang Welsch, “Ästhetisierungsprozesse – Phänomene, Unterscheidungen, Perspektiven”, in: ders., Grenzgänge der Ästhetik, 1996: 20.

Ibid, 20f.

Ibid, 21.

Ibid, 55.

For this position see Rüdiger Bubner, “Ästhetisierung der Lebenswelt”, in Ästhetische Erfahrung (Frankfurt/Main: Suhrkamp, 1989), 150.

This is Axel Honneth’s justified objection to this past discussion: See Axel Honneth, “Ästhetisierung der Lebenswelt”, in Desintegration: Bruchstücke einer soziologischen Zeitdiagnose (Frankfurt/Main: Fischer, 1994), 29f.

See Gerhard Schulze, The Experience Society (London: Sage, 1995).

For a critique on Schulze, see Honneth, “Ästhetisierung der Lebenswelt”, 37f.

For the more recent tendency, see Luc Boltanski & Ève Chiapello, The New Spirit of Capitalism (London: Verso, 2007).

On the justified critique of a reduction of life to the “disposable material of an individual who is proud of his autonomy”, see the discussion in Kritik der Lebenskunst, eds. Wolfgang Kersting and Claus Langbehn (Frankfurt/Main: Suhrkamp, 2007), 8.

See Michel Foucault, “What is Critique”, in The Politics of Truth, ed. Sylvere Lotringer (Los Angeles: Semiotext(e), 2007), 44.

See Axel Honneth, “Diagnose der Postmoderne”, in Desintegration, 18f.

Because there is a tension between the individual and the social good, which are nevertheless interwoven, both sides cannot be reconciled with each other by relegating them to two separate spheres, as Richard Rorty suggests when he locates self-creation in the private sphere and solidarity in the public sphere. See Richard Rorty, Contingency, Irony and Solidarity (Cambridge/UK: Cambridge University Press, 1989), 13f., 142.

See the compact determination of “démocratie à venir” in Jacques Derrida, Rogues: Two Essays on Reason (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2005), 86.

Claude Lefort, The Political Forms of Modern Society: Bureaucracy, Democracy, Totalitarianism (Cambridge/Mass: MIT Press, 1986), 305.

See also Jacques Rancière, Dissensus: On Politics and Aesthetics (London & New York: Continuum, 2010), 34.

Claude Lefort, Marcel Gauchet, “Über die Demokratie: Das Politische und die Instituierung des Gesellschaftlichen”, in Autonome Gesellschaft und libertäre Demokratie, ed. Ulrich Rödel (Frankfurt/Main: Suhrkamp, 1990), 102.

Ibid, 104.

Ibid.

Jacques Rancière, Disagreement: Politics and Philosophy (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1999), 102.

Ibid, 113. The self-emasculation of power thus goes along with the naturalization of a specific economic order, a specific form of capitalism.

Ibid, 114.

Superhumanity is a project by e-flux Architecture at the 3rd Istanbul Design Biennial, produced in cooperation with the Istanbul Design Biennial, the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea, the Govett-Brewster Art Gallery, New Zealand, and the Ernst Schering Foundation.

Category

Subject

Superhumanity, a project by e-flux Architecture at the 3rd Istanbul Design Biennial, is produced in cooperation with the Istanbul Design Biennial, the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea, the Govett-Brewster Art Gallery, New Zealand, and the Ernst Schering Foundation.

The text documents a lecture in which the author summarized some of the theses from her book The Art of Freedom. On the Dialectics of Democratic Existence (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2016) for discussion.