The New Old Gentry

Housing is meant to make our lives more comfortable from the outside. Besides walls that protect us from hostile circumstances, we have equipped the interior with an accumulation of tools and devices. To be spoiled by all those belongings has only been followed by even more things. Digitalization marked a shift in the minimalism of interior design; while it was first about shrinking, smoothing, and hiding those tools and devices, 3D printing and the Cloud enable us to live with almost nothing aside from what we need at this very moment.

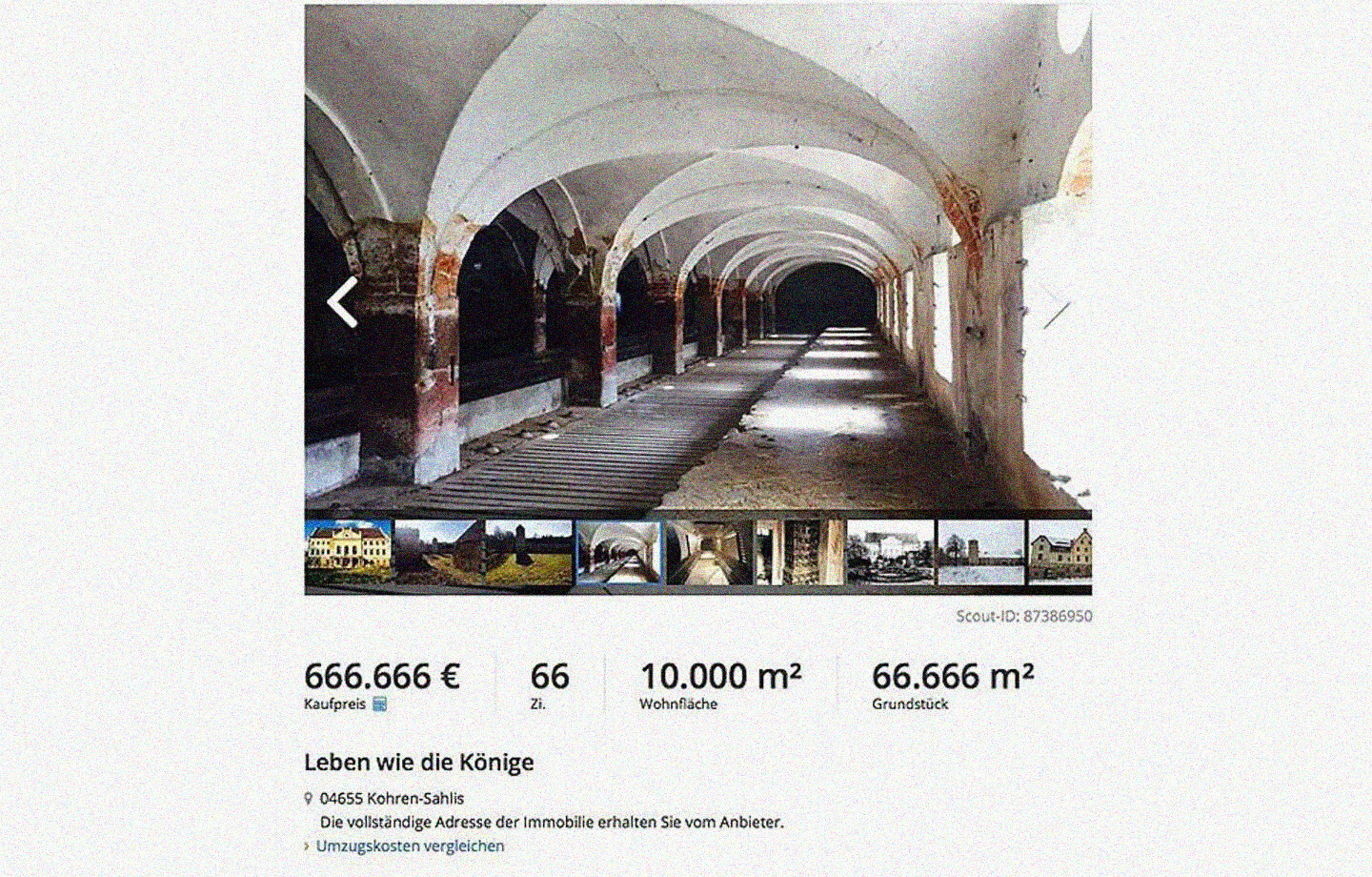

The only thing that cannot be expanded out of nowhere is our exclusive living area. Earth’s surface is fixed and the population continues to grow while further building is restricted. The result is a cult of vast, empty, naturally lit space, in densely populated areas, if possible. After thousands of years of civilization and mass murder, we are talking square meters. The medium-rich are selling shares or their companies to buy architectural jewels, devote years of their lives to polishing them, live in them like in a shrine, and make a living by occasionally renting it out for special occasions.

Walled space has become the ultimate luxury. Even more everyone needs a minimum of shelter—to have a place to put a bed and your clothes is just as important as having an address to gain the status and benefits of a full citizen. Still, while lots of states guarantee their inhabitants food, clothes and health care, they don’t guarantee shelter. At most they pay your rent up to a certain amount.

Virtually everywhere on Earth the prices to rent or buy residential space have been rising faster than the average income, the result of which is a self-fulfilling prophecy of mass speculation for a further rise in prices. If you don’t buy a house or apartment now, you probably won’t be able to afford a similar one for the rest of your life. You are under the gun to start climbing the real estate ladder as fast as possible, and to already include space for your eventual kids so that you won’t be forced to move to a worse part of town when you actually start a family. Couples stay together only because of the decent piece of real estate they once got together. Maybe the piece of real estate is so exquisite that it becomes the true love interest, effectively turning the marriage into a menage a trois. Ghost, 9½ Weeks, Sleepless in Seattle … since the 1980s, many famous erotic thrillers and romantic comedies show an uninhibited level of real estate porn.

Nothing has created more millionaires than the worldwide boom in real estate. Yet at the same time it enslaves a majority of people to a life-long mortgage and flawless career. With prices for real estate skyrocketing, it gets harder and riskier for every new generation to secure decent housing with their income. Even if you could sell something you were able to buy and make a profit worth a couple of annual salaries, it wouldn’t be worth moving into a cheaper area as its underperforming job market and poor infrastructure would cost you even more.

A decent inheritance is the last chance. People who don’t have to pay their rent or take out a mortgage are the new old gentry: highly privileged but often hardly solvent. Maybe it’s the creative class, but I know an increasing number of people who own huge flats and have hardly enough to eat. The rising cost of utilities are eating them up, and renting out the flat can be against house rules. Or, renting can make property lose value. In Germany, this can be up to fifty percent, as it’s quite difficult to kick out tenants, and rent can only be increased slowly without renewing the contract. As a result, many private owners rather keep their property empty or only offer it on Airbnb.

Airbnb officially started as the possibility to rent out your flat when you are not home, or to rent out an extra room when you don’t need it. But in fact, Airbnb reduces permanent living space, and by increasing the possible income from owning flats or houses, their prices are being pushed up even further.

The Landlord’s Guilt

Six years ago I had saved and inherited enough money to buy a decent flat in a mildly gentrified part of Berlin. Compared to other European capitals and many other German cities, prices in Berlin were still amazingly low, just like the rents and wages. The population hadn’t been growing since reunification, even though Berlin was Germany’s new capital and the country’s economy was finally booming again. Berlin’s economy was still doing bad and there weren’t enough international bohemians moving to the city to compensate for a new suburban flight. During the Cold War, the Western, capitalist part of the city had been encircled by a wall, and the Eastern, socialist part had left people without personal fortune, so the possibility to build your own house outside the city was still new.

But the global 2008 economic crisis in general, and the 2009 Euro crisis in particular, was about to have a drastic impact on Berlin’s real estate market. The crisis had been triggered by mortgages being belligerently issued to Americans with precarious income. From a self-fulfilling prophecy, the housing boom had turned into a worldwide pyramid scheme. To stop the crisis, national banks flooded the market with cheap money. Yet as interest rates were plummeting, where could money be safely invested? Again, the main idea was private housing.

Whether at art events in Berlin or private parties in Nairobi, everywhere I would hear people talking about Berlin’s spectacularly cheap real estate. People hardly knew the city but their pronunciation of upcoming quarters like Moabit, Schöneberg or Neukölln was remarkably good.

I had been based in Berlin for more than twenty years and finally I could profit from my deep knowledge of the city. Different from the outsiders, I would focus my search on Wedding, a part of the city where I had been living for a couple of years. Wedding was neighboring Mitte, the historical center of the city, and despite its exquisite location gentrification was still sparse.

The longer I searched, the more it became clear that it would be hard to find a flat that I would like as much as the one where I lived. My flat was small but extremely quiet, had a lot of light and a spacious balcony. Situated on a pedestrian road with no shops, gentrification could not manifest in an accumulation of neat cafes and shops. And still, Mitte and Prenzlauer Berg were only a stone’s throw away.

But of course, my rent would rise and the house could eventually be sold to a rigorous investor or even torn down. Besides, at some point in my life I might stop traveling so much and be fed up with living on my own in only one room. So I continued to search for a two- or three-room apartment in Wedding. As I wouldn’t need this apartment right away, my search wasn’t limited to ones that were already free. I wouldn’t want to be a mean investor, and I would be fine as long as the current tenants paid enough rent to cover running costs and taxes.

Only when I visited the first flats I realized that either I detested the tenants so much that I would never be able to deal with them, or I liked them too much to make them fear that one day I could kick them out to move in myself. Just the idea of standing again in someone’s apartment as its potential owner became unbearable. Renting out an apartment was far too personal to be acceptable as a business relationship. I couldn’t do it, just as I could never go to war. I’d rather lose the opportunity to live decently in the future.

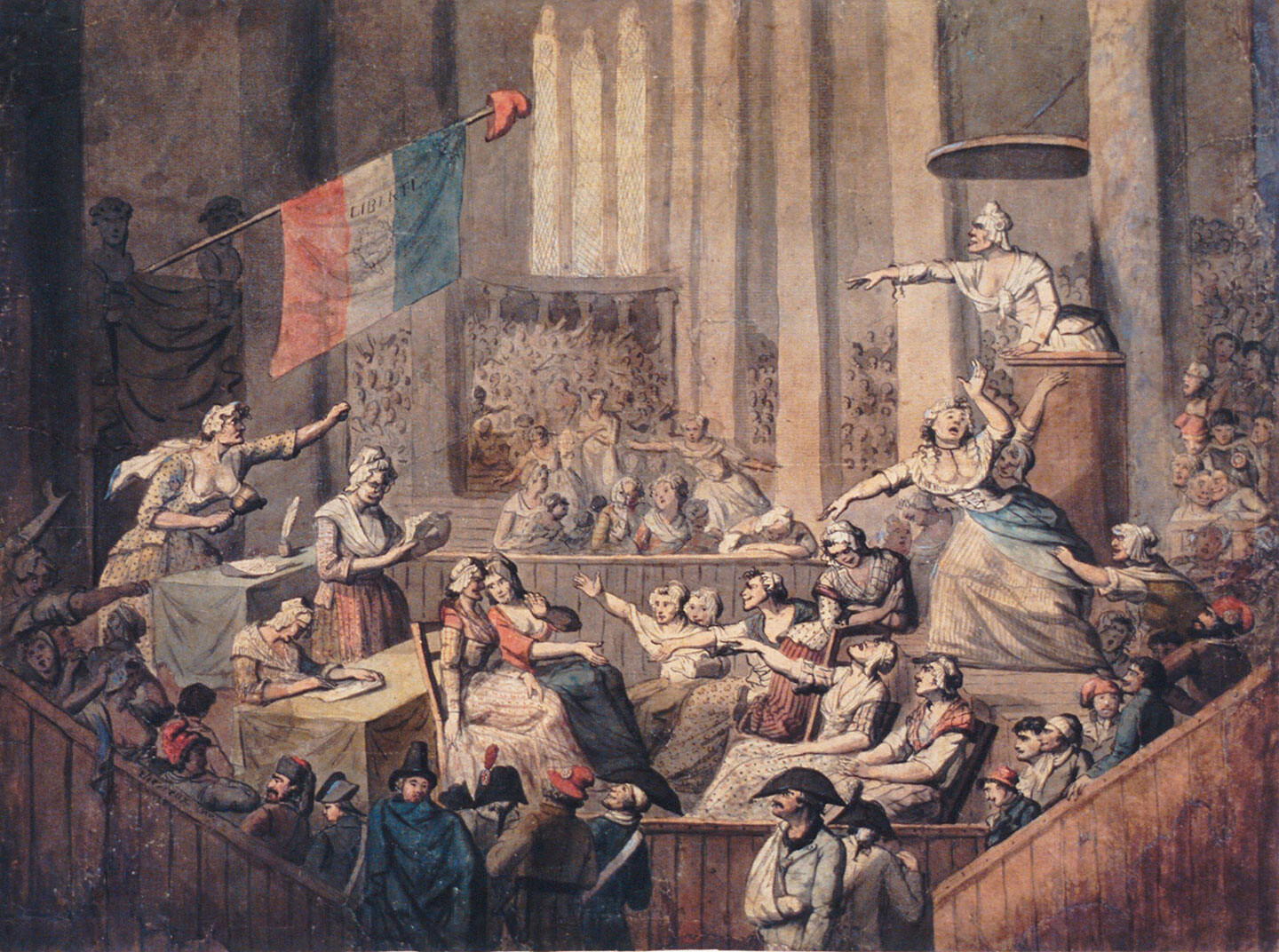

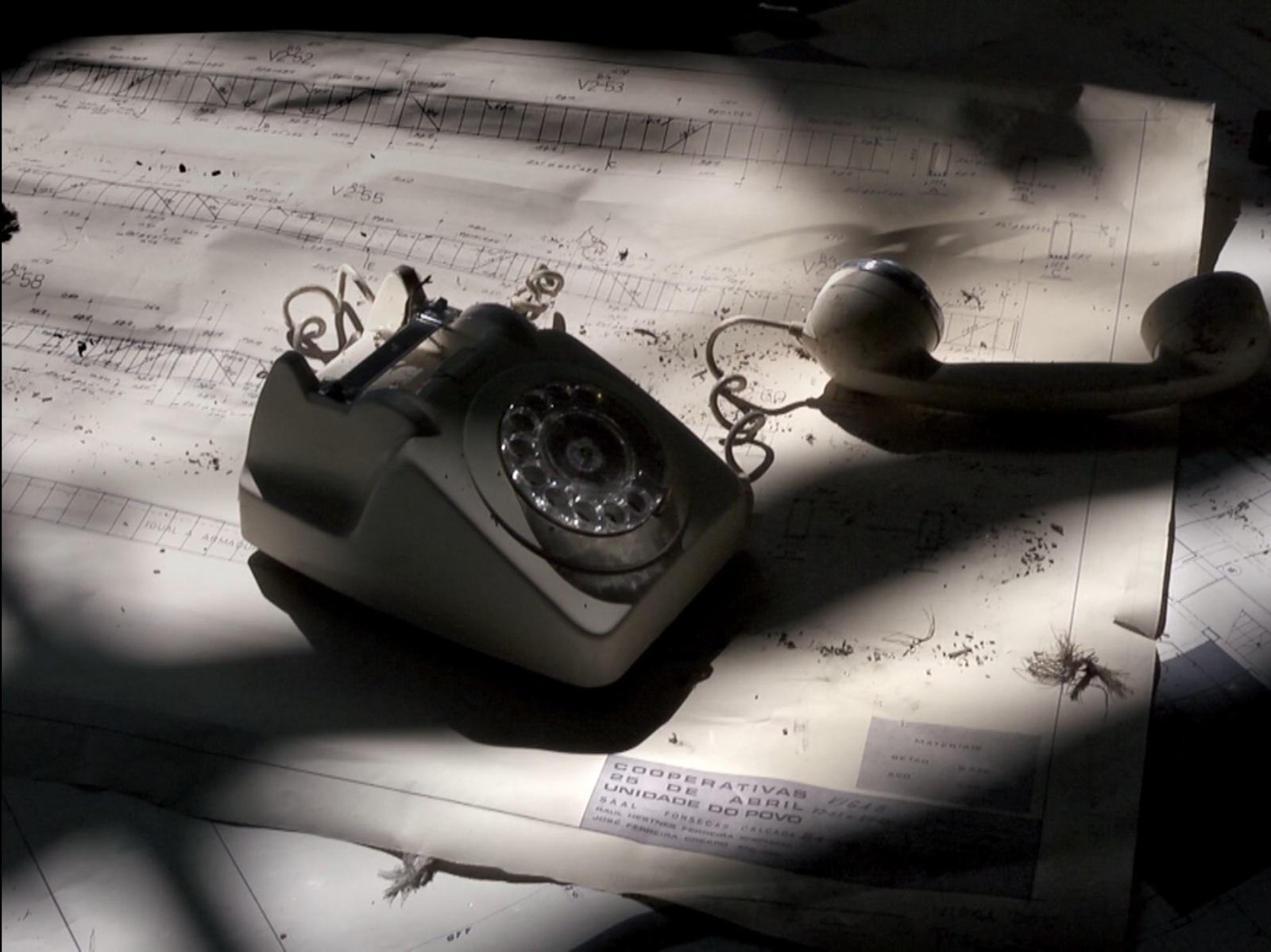

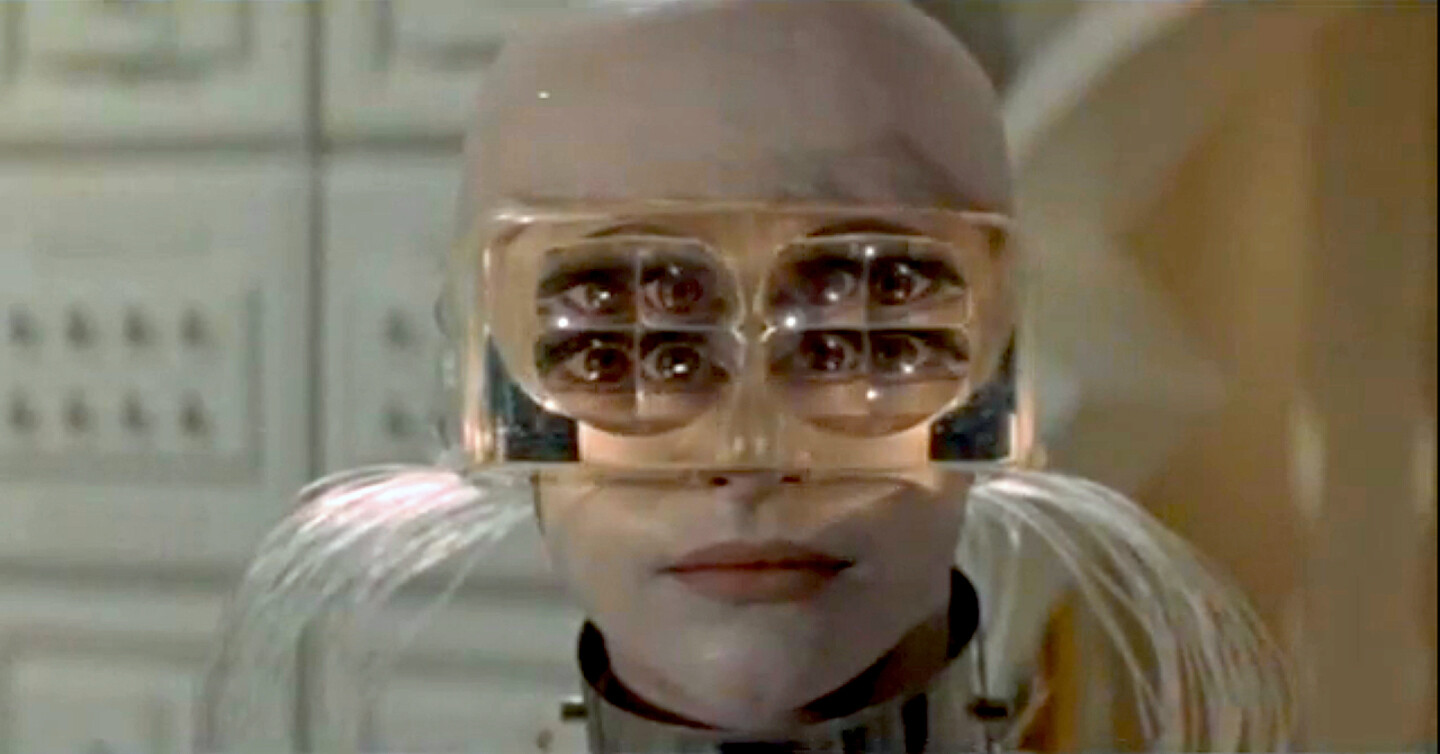

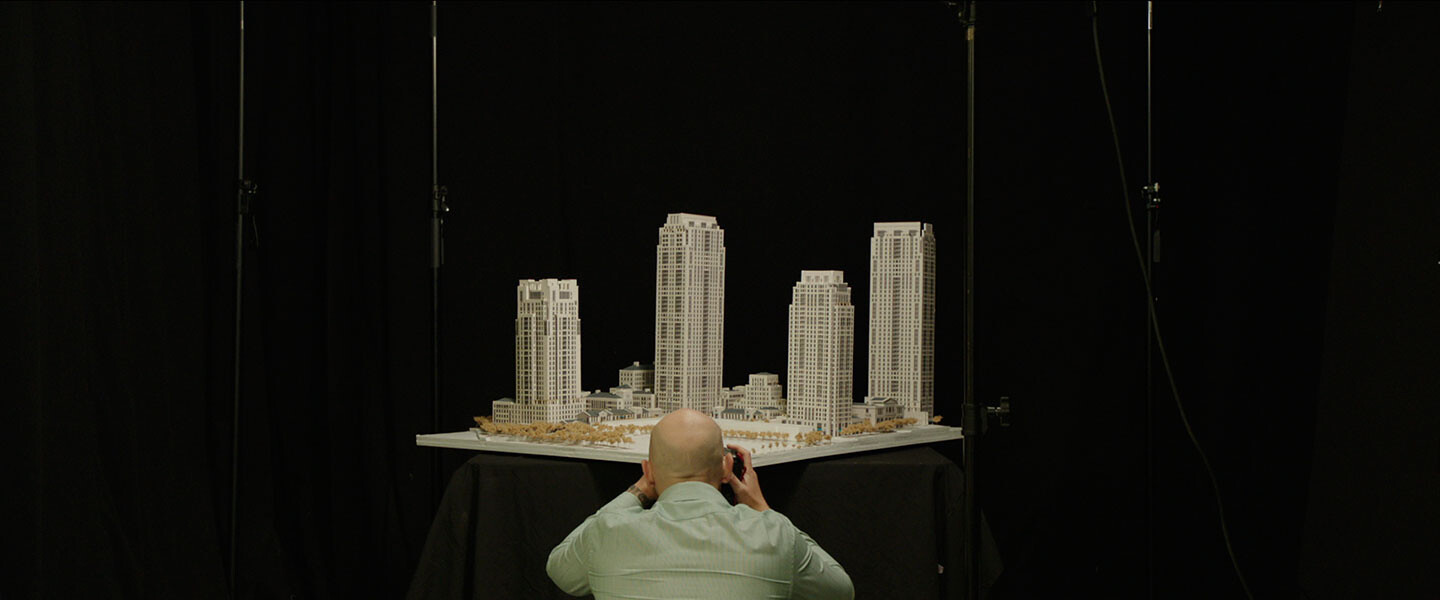

Amie Siegel, The Architects (still), 2014, HD video, color/sound. Courtesy the artist, Storefront for Art and Architecture, and Simon Preston Gallery, New York

The Housing Lottery

The fear of losing your familiar shelter might be banal compared to the fear of dying from sudden cancer or being killed. In the worst case you have to commute longer, have less space and less sunlight. But unlike finding a job or staying healthy, we get no practical support in securing our living space (neither from scientists nor from politicians), making it one of the things that causes us to feel most responsible for ourselves. A large part of our courage and energy is absorbed by finding and paying off a proper living space. Real estate is the enemy of love, fun and generosity; it makes our lives fearful and boring. We don’t own our houses, but our houses own us.

What have you been doing all your life?

Oh, I secured a really nice piece of property. Unaffordable by now.

Only for some of the really rich is it not enough to reside in architectural jewelry, who instead feel compelled to activate their villas, gardens, and islands for very special moments and encounters, or transform them into residencies for artists or shelters for refugees.

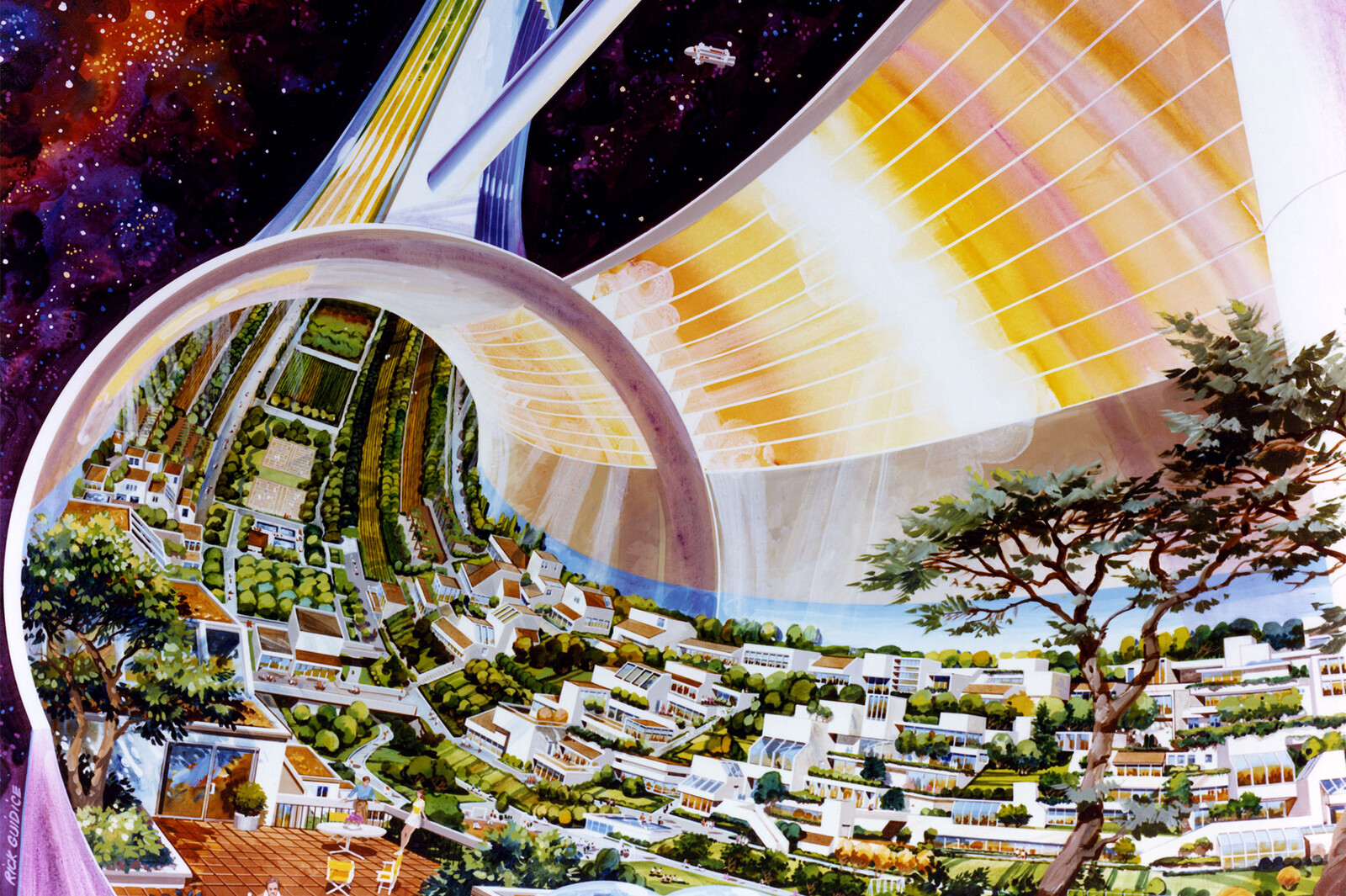

What would a society look like that provides generous hospitality to everyone? A “basic habitat”—similar to a basic income—is not easy to offer. People have different needs and desires, and existing houses cannot be cut into similar slices like in a land reform. But every or every-other year there could be a compulsory lottery to redistribute housing among an entire population. As personal material belongings are no longer so relevant, moving from one space to another is simple. And if you were to draw a small space, you could put most of it in a storage. You could also put it on display from time to time at a public showroom. Conversely, if you draw a huge space, you can earn extra money with aquaponics, an illegal swap, or the production of actual real estate porn.

The redistribution lottery is a transitory phase untill genetic engineering (a la CRISPR) will enable a future us to comfortably live outdoors in any climate. When that time comes, there’ll be endless virtual possibilities to find seclusion, when desired. People who continue to insist on a vast physical space just for themselves will appear as an inacceptable burden on the environment.

Superhumanity is a project by e-flux Architecture at the 3rd Istanbul Design Biennial, produced in cooperation with the Istanbul Design Biennial, the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea, the Govett-Brewster Art Gallery, New Zealand, and the Ernst Schering Foundation.

Category

Superhumanity, a project by e-flux Architecture at the 3rd Istanbul Design Biennial, is produced in cooperation with the Istanbul Design Biennial, the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea, the Govett-Brewster Art Gallery, New Zealand, and the Ernst Schering Foundation.