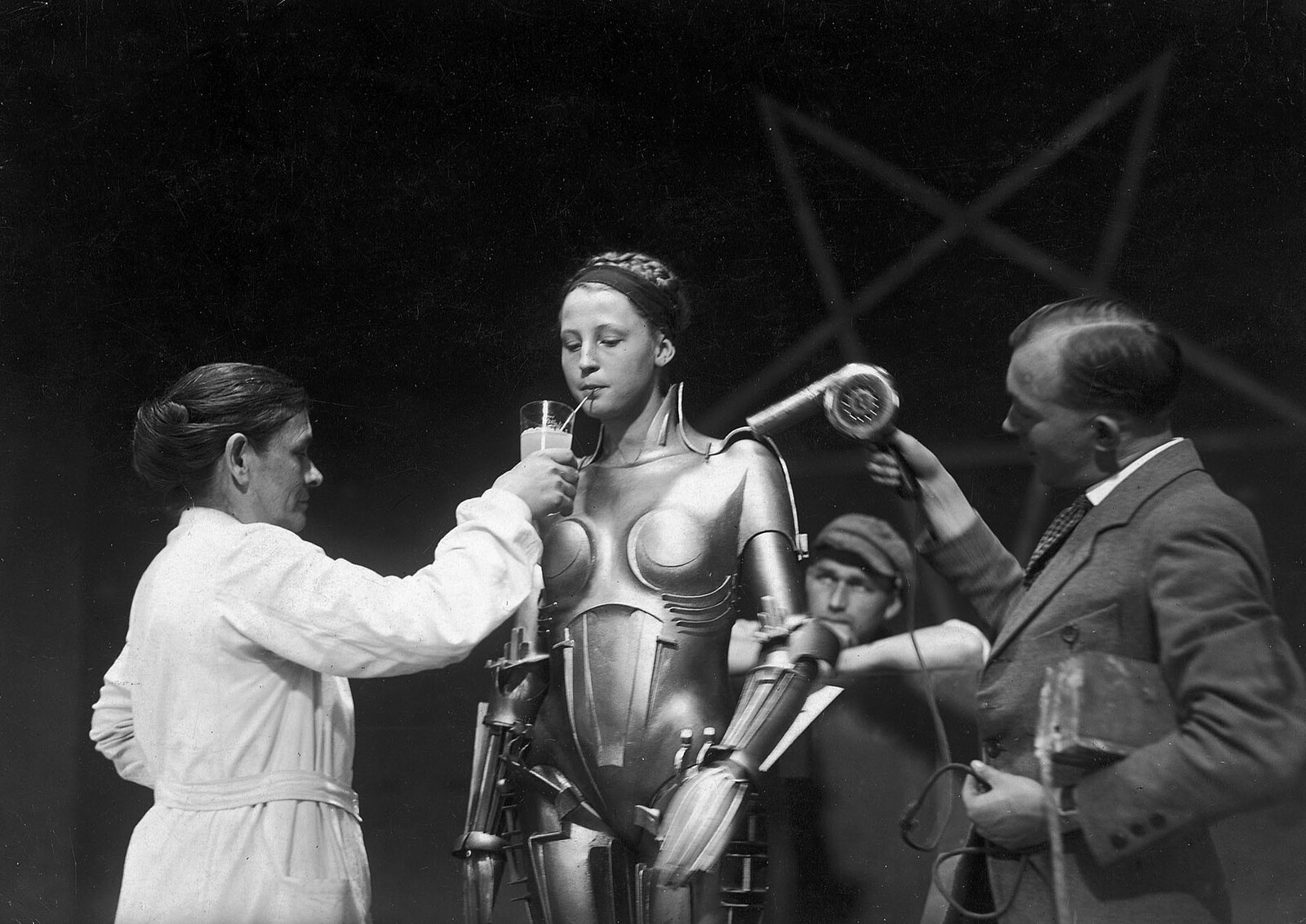

In the 1950s, the famous American psychiatrist Bruno Bettelheim treated an autistic boy named “Joey.” After ceasing all communication with the world, Joey began to think that he was a mechanical robot. He could only fall asleep after connecting his body to a complex set of machines, both imaginary and real, on his bed. The images he drew, of houses, isolated rooms, and moving vehicles full of machines, contributed to Bettelheim’s diagnosis. In working with Bettelheim, Joey slowly overcame autism by driving out his acquired identity as a machine and recovering humanity. As Joey improved, he began to draw nature alongside machine, such as people driving cars. Bettelheim’s report concludes with a description of Joey at a Memorial Day parade holding a picket sign that says “feelings are more important than anything under the sun.”

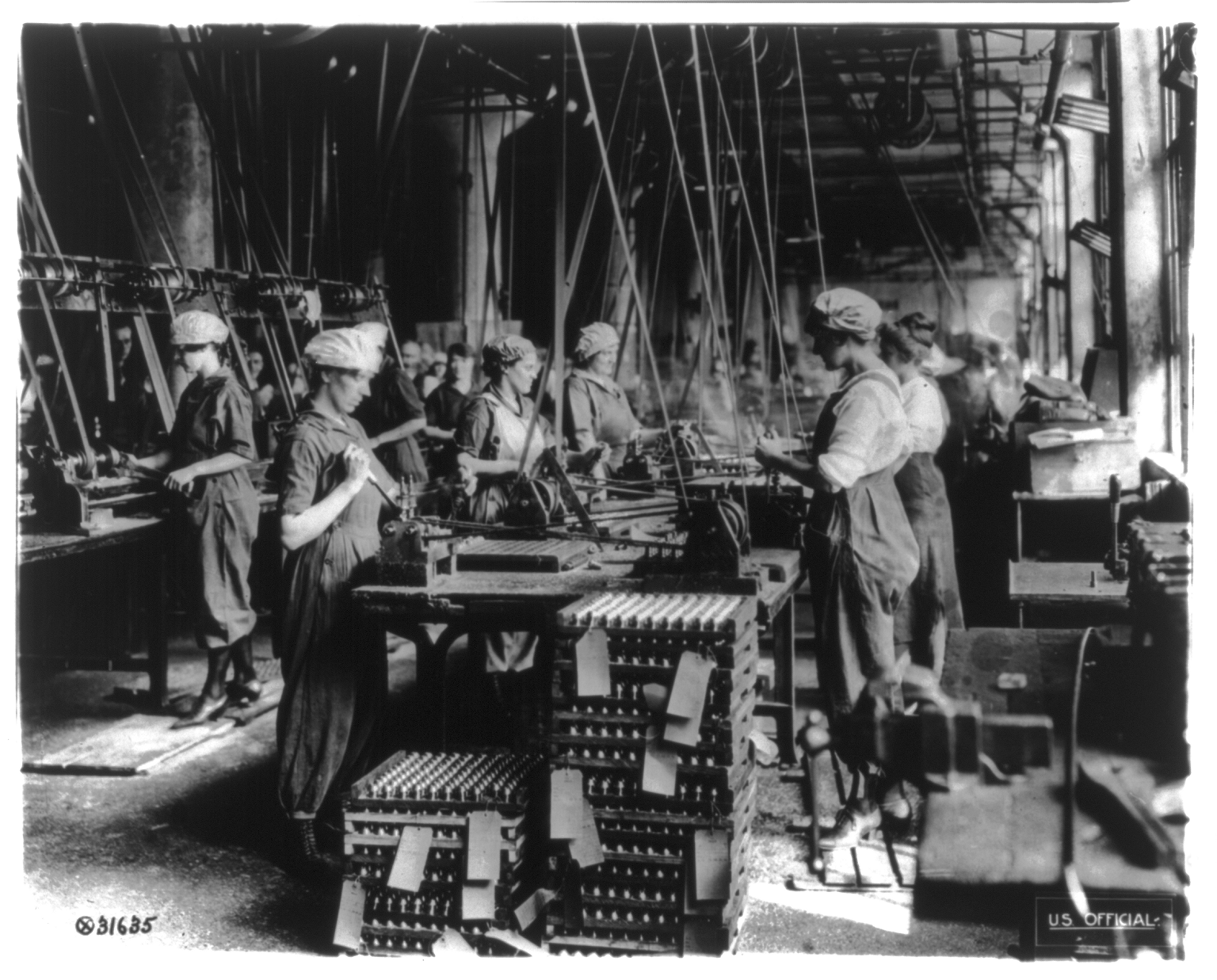

Back then, humans and machines were largely assumed to be adversarial. Using a thermodynamic figure of speech, if the sum of humanity and technicity was presumed to be constant, the increasing autonomy of machines would necessarily lead to the contraction of humanity. Bettelheim worked with an understanding that the technicity that dominated young Joey suffocated his humanity, and thus caused his autism. In light of posthumanism, actor-network theory, and a critique of anthropocentrism, Joey’s case demands to be interpreted anew.

At the time of Bettelheim’s experiment, the term “child schizophrenia” was used more often than autism. In fact, the word “schizophrenia” was even used to characterize the time. Erich Fromm, for instance, wrote that “in the nineteenth century, inhumanity meant cruelty, but in the twentieth century it means schizophrenic self-alienation.”1 Similarly, Günther Anders, through dialogue with Major Claude Eatherly, the “hero of Hiroshima” who was later diagnosed with schizophrenia, claimed that a reality in which mass destruction by nuclear weapon is possible makes people schizophrenic and act like “isolated and uncoordinated beings.”2 Henry Kissinger’s 1957 Nuclear Weapons and Foreign Policy warned that a limited nuclear war against the Soviet Union was indeed possible, and Herman Kahn, a nuclear strategist at the RAND Corporation, similarly claimed that if a nuclear war against the Soviet Union were to take place, the United States would suffer from approximately sixty million casualties, but could win and rebuild society quickly afterward. But on the other hand, many respected scientists warned that nuclear war was a dangerous gamble that could possibly bring the annihilation of humankind, and reports were published on the lives of the survivors of Hiroshima’s atomic bombing, claiming they were worse than death. If both sides were speaking with the “authority of science,” which should be taken as truth?

At the same time, schizophrenia also figured as a key term within cybernetics and communication theory. Gregory Bateson, for instance, created the concept of a “double bind” to understand schizophrenia, which he put forth after studying communication in the family of a schizophrenia patient. Simply put, Bateson’s double bind refers to the situation where contradictory messages are continuously imposed on someone; a well-worn example of this is a mother coldly scolding her child while saying, “I love you.” Continuously exposed to such messages, the child becomes unable to understand which message is real and gets confused, potentially resulting in schizophrenia. In cybernetics, this would be an instance of the feedback loop between input and output being broken.

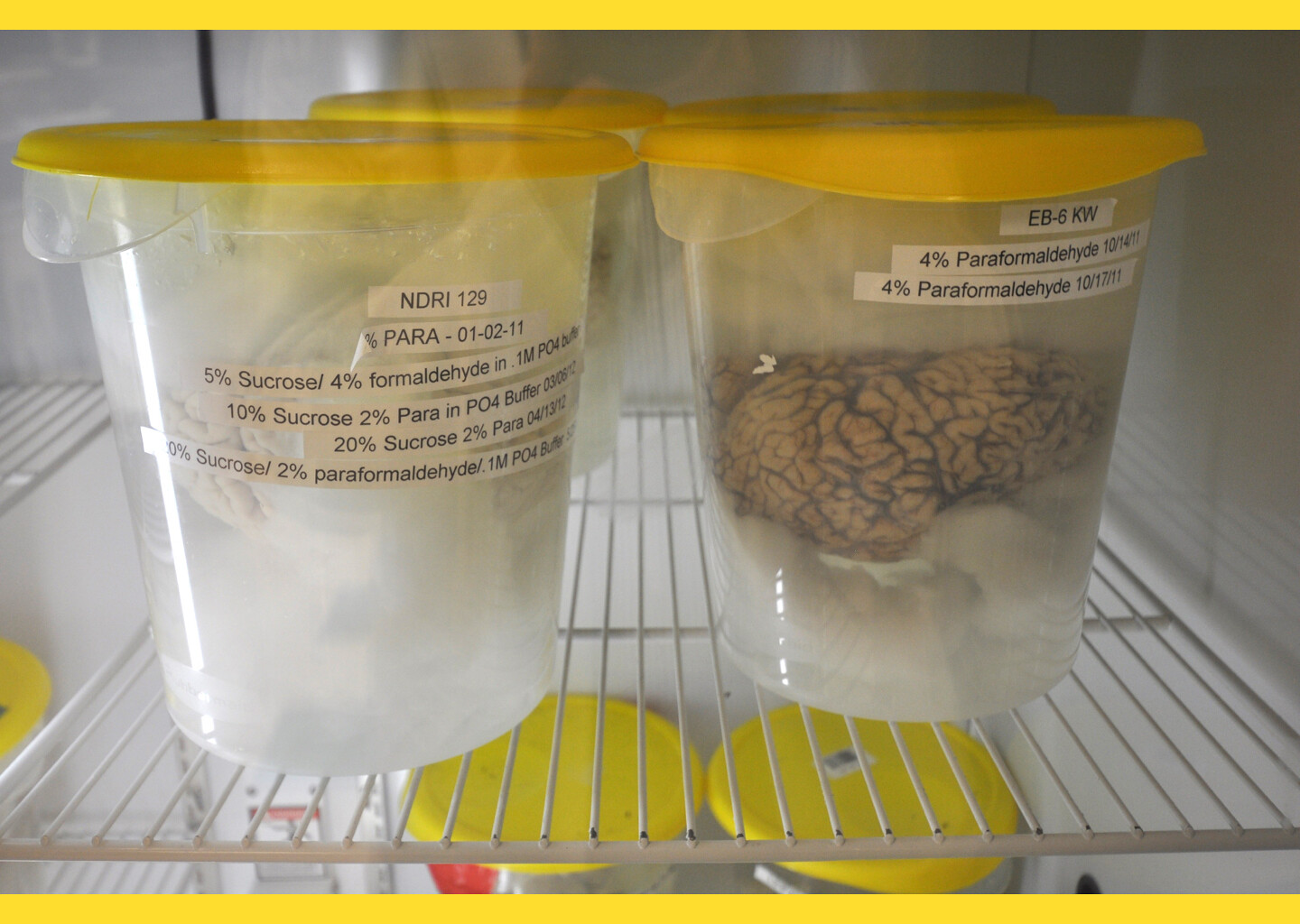

Bettelheim, director of the Orthogenic School for Disturbed Children at the University of Chicago, turned Bateson’s double bind theory into a more approachable theory for the public. Bettelheim contended that cold and apathetic mothers who think their children “should not exist” cause them to develop schizophrenia, a theory commonly referred to as “Refrigerator Mother Theory” or “Schizophrenogenic Mother Theory.” He claimed that in an ordinary family, the existence of an authoritative father compensates for the mother’s apathy. However, in America at the time, this authority could not be maintained as the number of fathers who died or were physically or mentally injured during war grew, which resulted in children whose apathetic mothers failed to form emotional bonds with them and increasingly drove them to mental illness.3

Bettelheim’s 1959 Scientific American article “Joey: A ‘Mechanical Boy,’” which condemned apathetic mothers as the cause of child autism (schizophrenia), attracted public attention.4 According to Bettelheim, Joey’s mother did not realize that she was pregnant, and when she gave birth, did not have a strong emotional connection to the child. Joey’s father was a young veteran who was also uninterested in raising children. Joey cried all day, and his parents let him. They fed him at regular intervals. His mother gave him very strict toilet training because it would ultimately save her time. At the age when he started speaking, Joey already showed interest in machines, such as fans, and was adept at disassembling them, but would only talk to himself, not others. “By treating him mechanically,” wrote Bettelheim, “his parents made him a machine.”

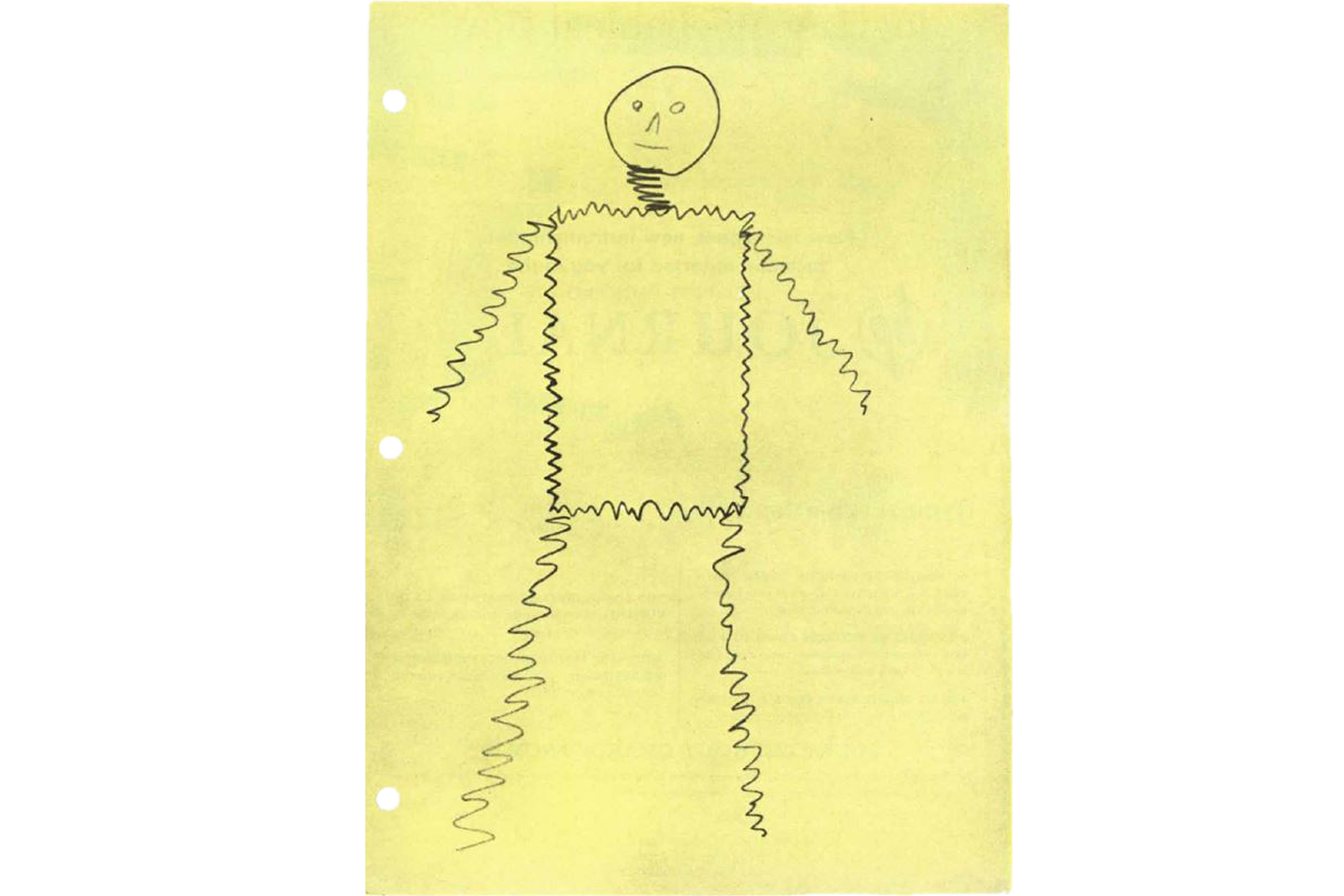

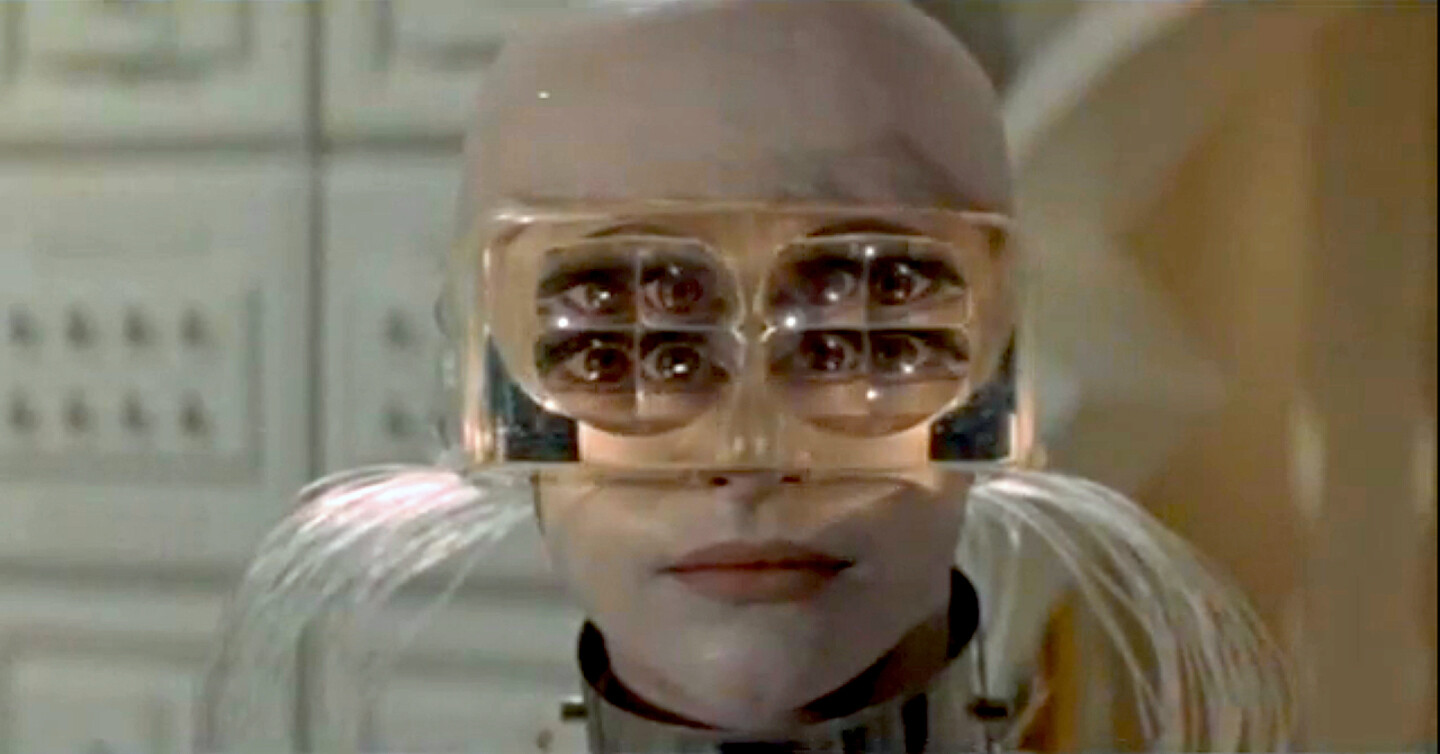

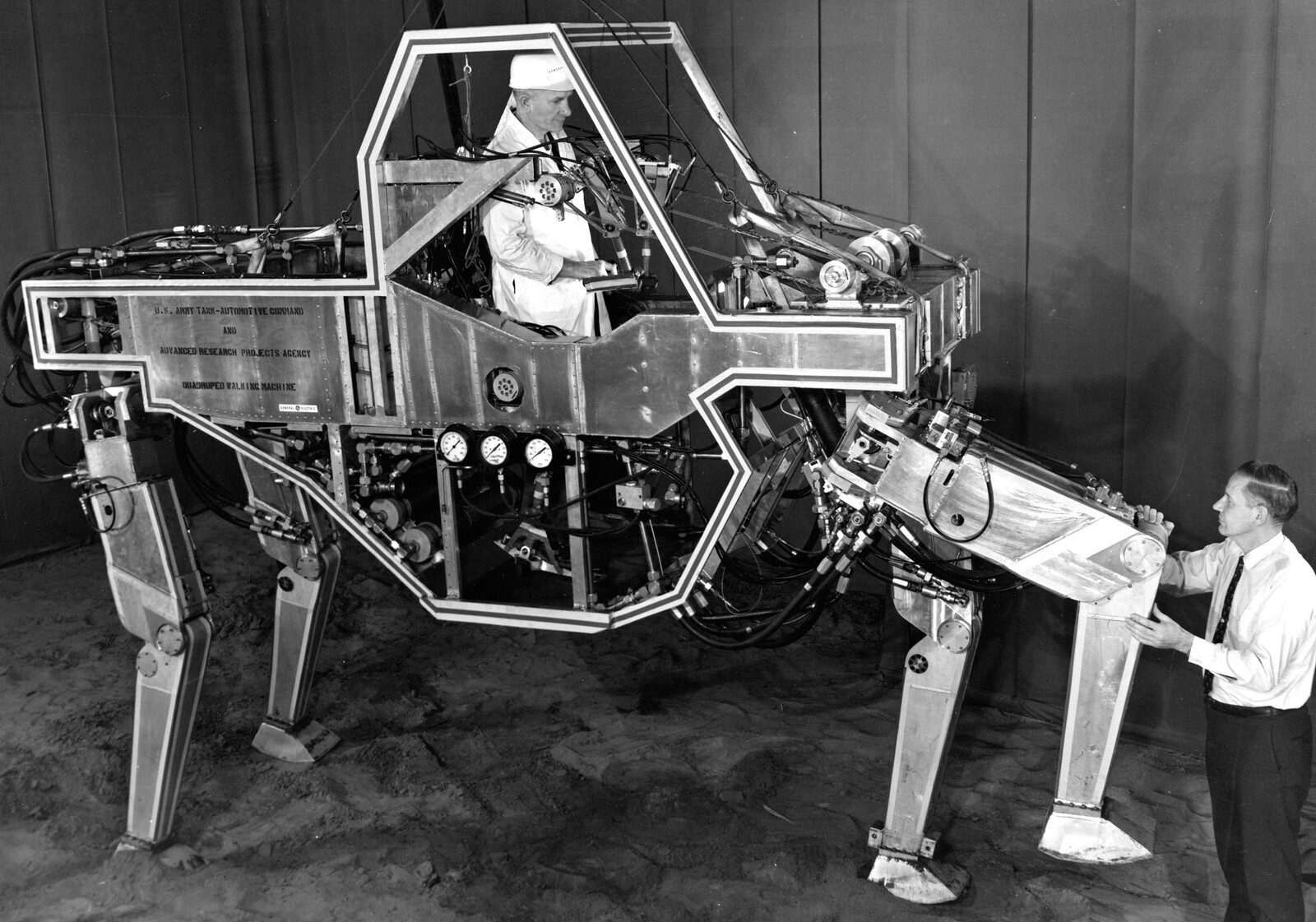

Not being able to adjust to a regular school, Joey was sent to an alternative school at the University of Chicago. During his first visit, Joey felt as if he was supplied with electrical power from an invisible source. Joey felt that he could only survive if he was connected to a power source. Other students had to take care not to step on the invisible power lines. Joey installed tubes and motors around his bed, insulated himself with napkins, and slept with his body “connected” to these apparatuses. He would not address people by name when talking to them, but would give each of his machines names. He believed that his machines controlled him and gave him orders. One of his machines was the “criticizer,” which prevented him from feeling unpleasant feelings.

Joey saw himself as a machine. He thought, for instance, that his brain had to be replaced with machinery when he forgot something or made a mistake; when he dropped something, he thought that his arm must be broken since it failed to function correctly. Bettelheim said that Joey not only had a mechanical body but also mechanical feelings: when he was rejected by another child who he got close to, Joey said, “He broke my feelings.” Joey would make complicated machinery, take it apart, and put it together again. Bettelheim interpreted this destructive behavior as a brief recovery of human identity, but with the reconstruction that followed, it did not last.

Bettelheim began his treatment by teaching Joey that he could do things by himself, autonomously, without the aid of machines. The first was bowel movements. When going to the bathroom, Joey had to bring an imaginary vacuum tube and hold it against the wall to receive energy to push the excrement out. After Bettelheim made him use a portable toilet instead of visiting the bathroom, Joey became able to have bowel movements without the tube. From then on, Joey started building relationships with the world little by little, and was able to gradually separate himself from the mechanical environment that surrounded him.

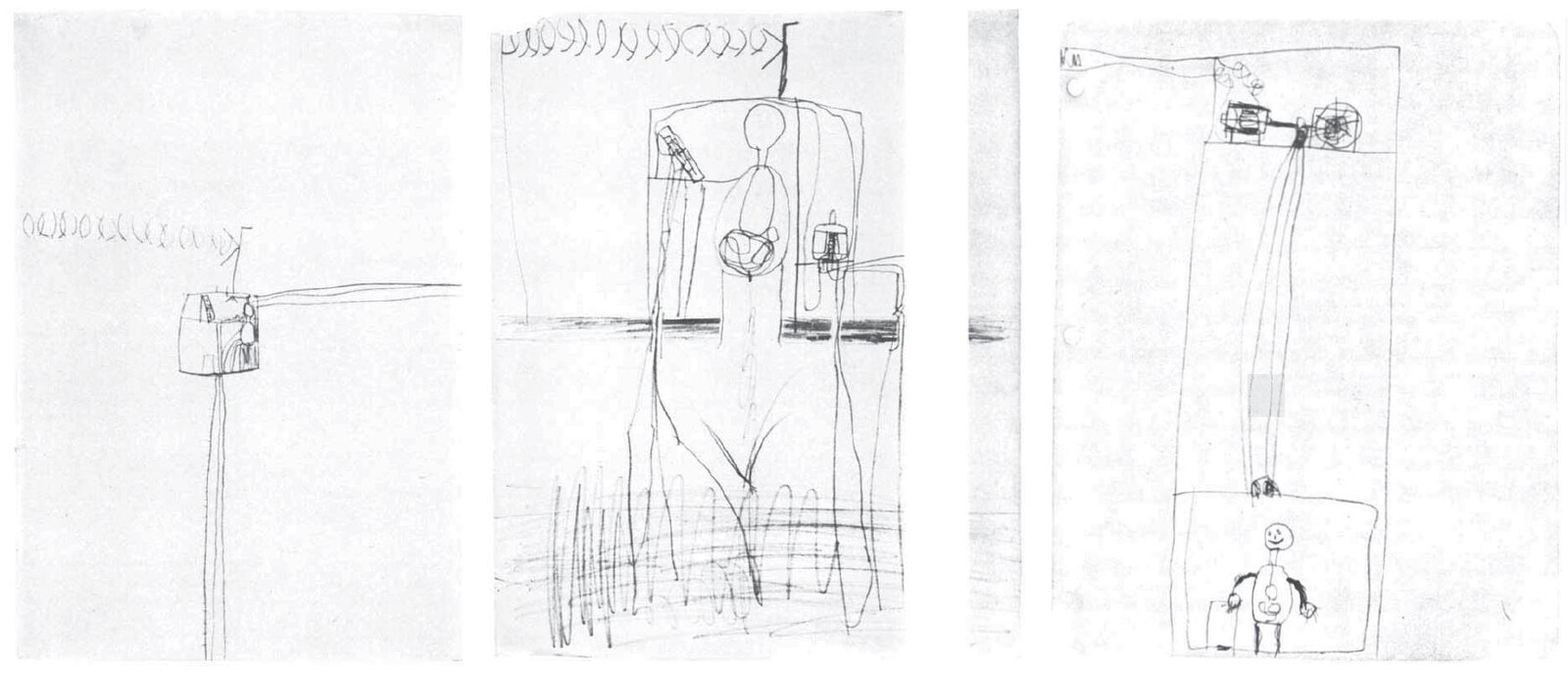

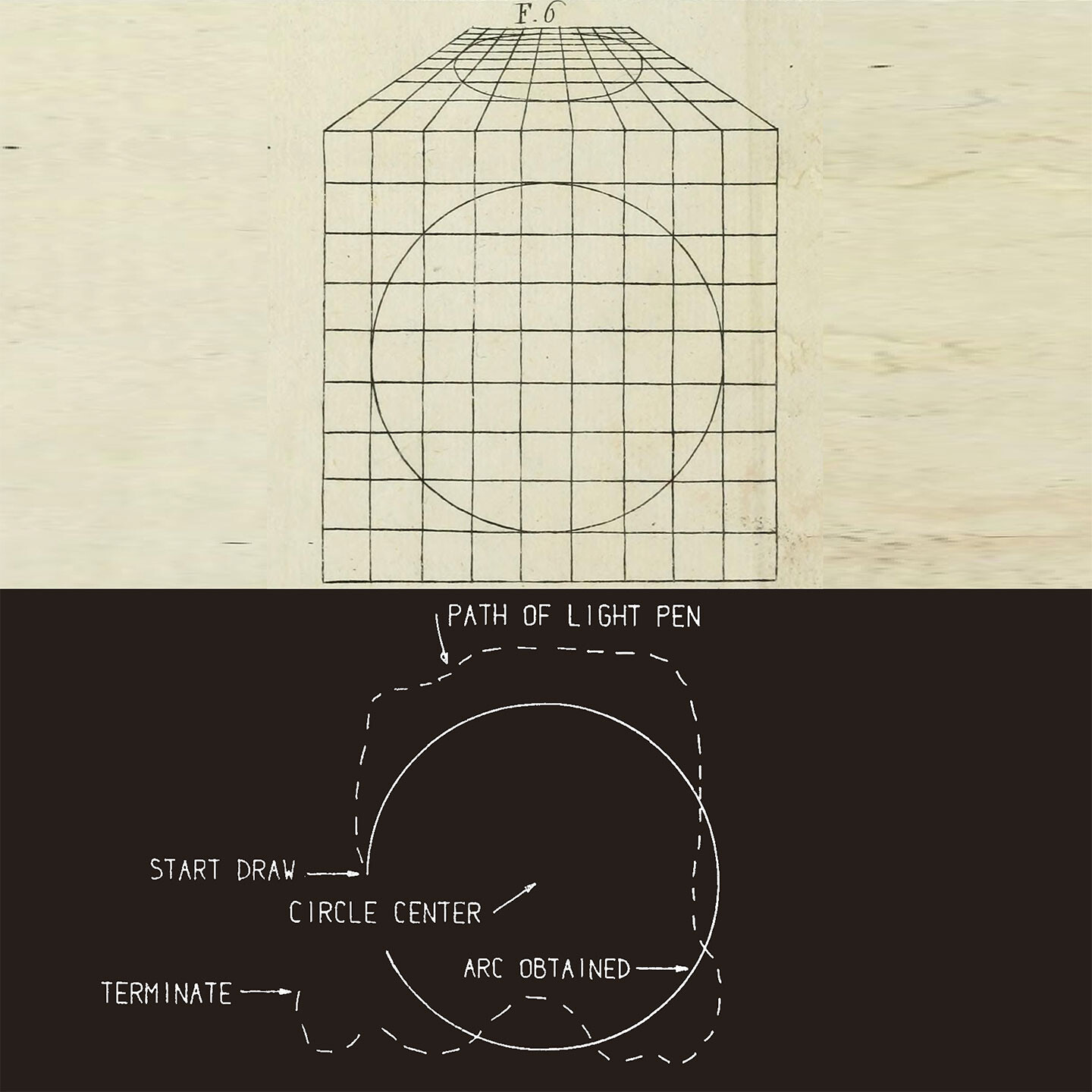

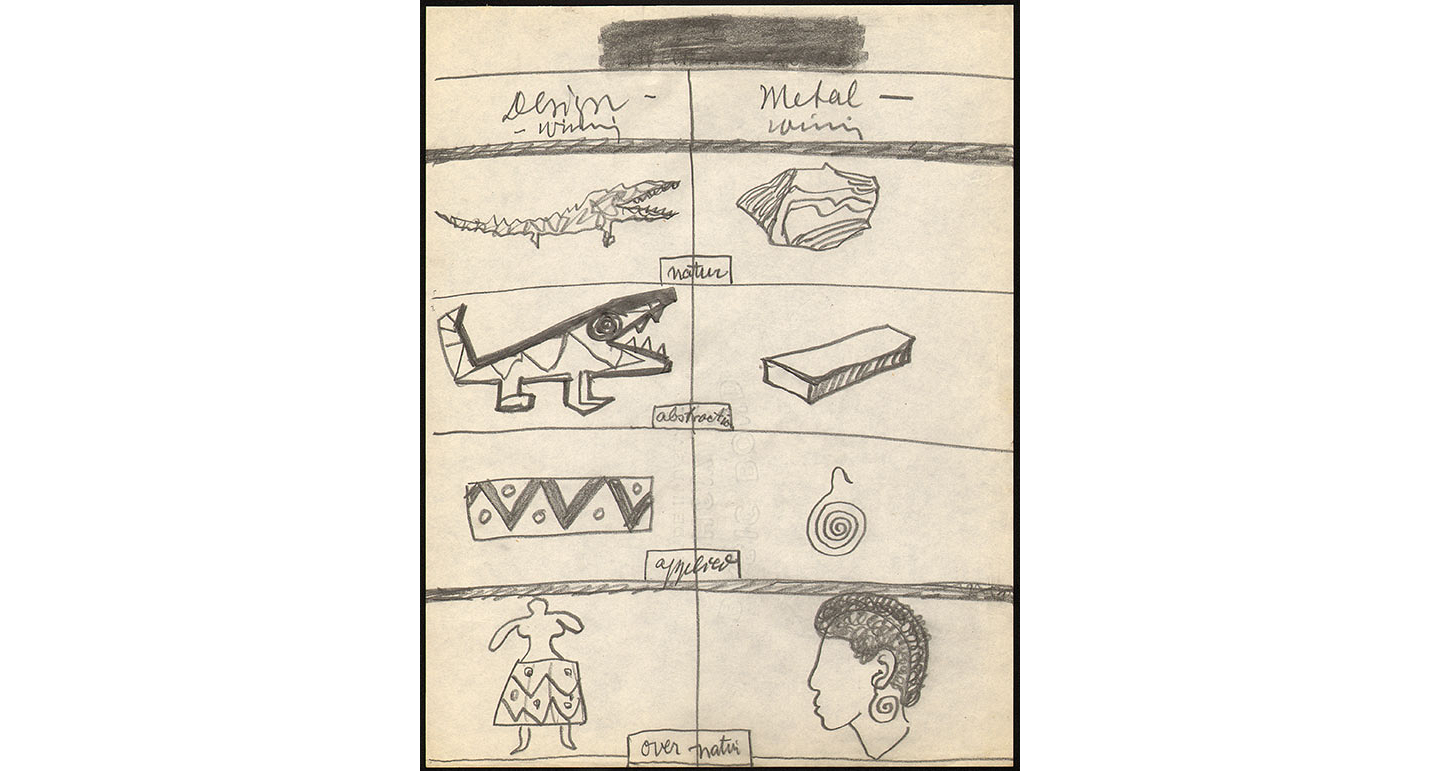

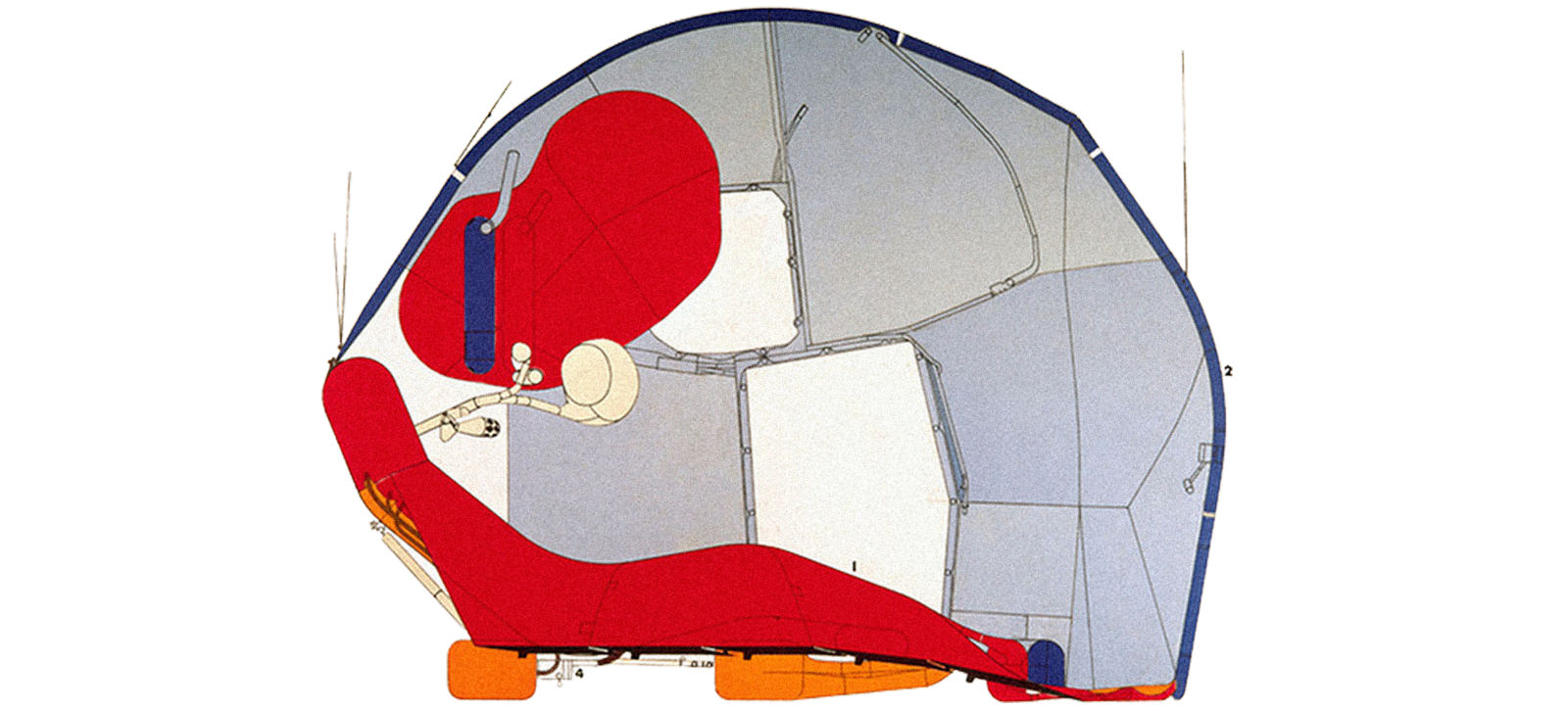

Along the way, Joey produced numerous drawings. One series that Bettelheim analyzed consisted of three drawings. He described the first drawing as Joey’s “mechanical womb,” which he interpreted as Joey’s growing self-esteem. In the second drawing, a figure with visible internal organs sits on a toilet in a bathroom. On the left there is a machine that looks like a radio or a TV, and on the right there is something that looks like a motor. Wires connect the machine to the motor, and the child to both, as in the first drawing. In these first two drawings, the room is connected to the world through some kind of wireless apparatus, whose function is unclear—perhaps it provides power to the devices. In the third drawing, however—which otherwise resembles the previous two—the “womb” is hardwired to the world. Moreover, the machines are not directly connected to Joey’s bowel movement, but nor do the machines completely disappear. Bettelheim interprets this drawing as showing that Joey’s hands can control his environment, and the machines are separated from the room.

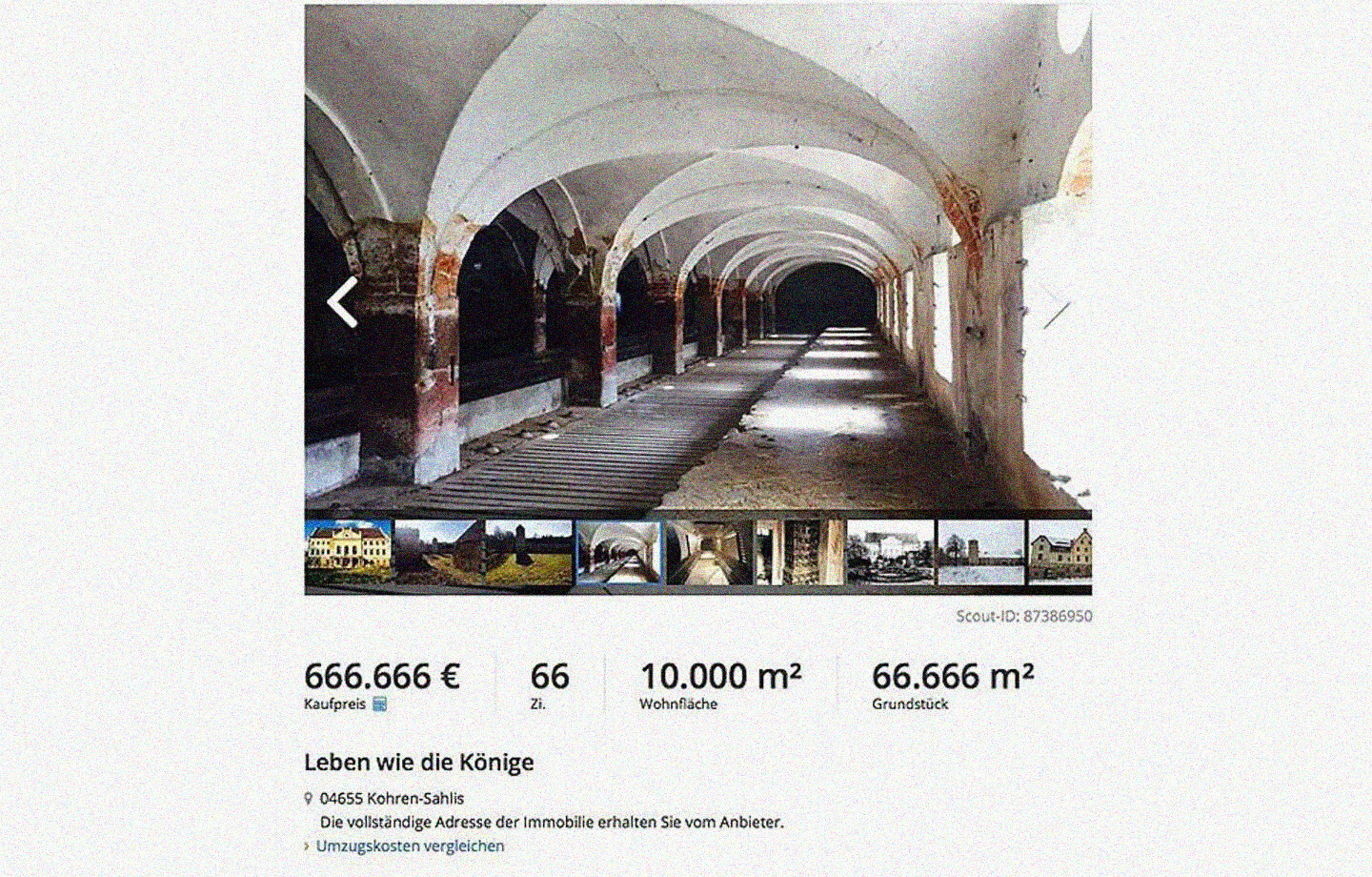

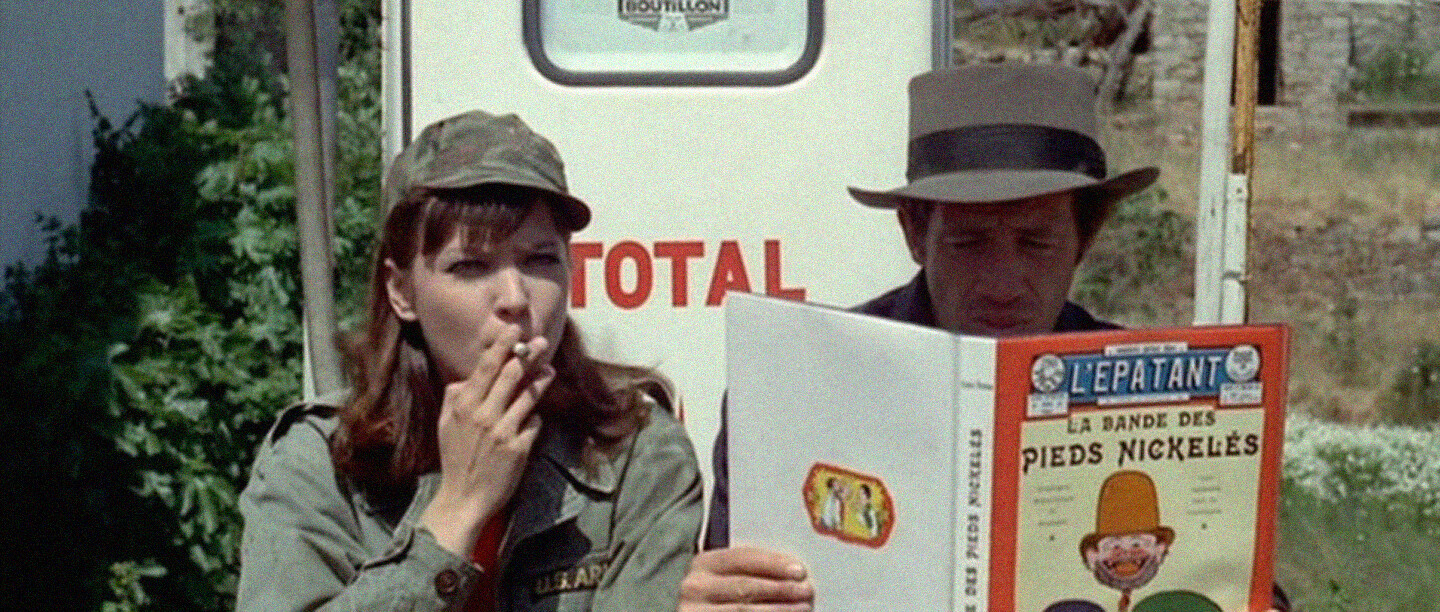

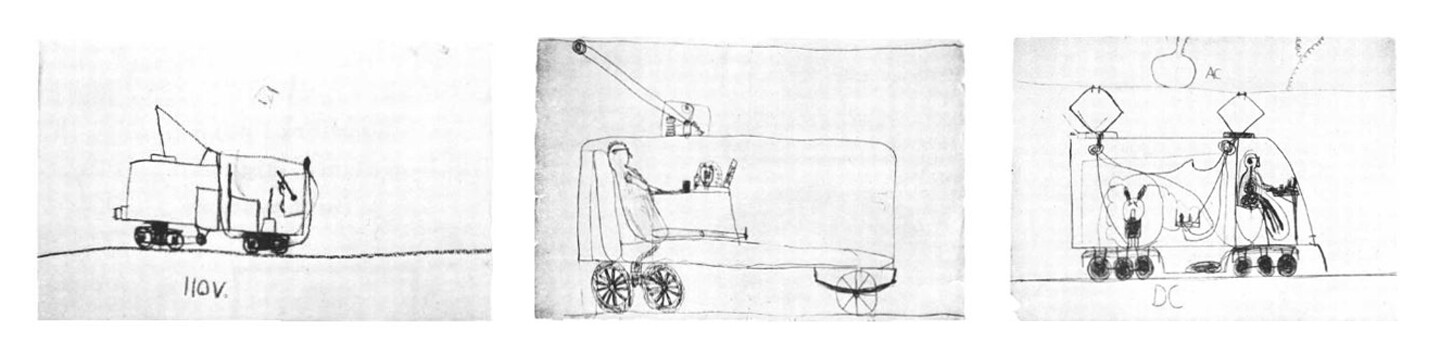

Joey’s “Carr Family” drawings.

Another series of drawings that Bettelheim analyzed were Joey’s “Carr Family” drawings, which he interpreted as demonstrating Joey’s “growing autonomy.” According to Bettelheim, while there is no human in the first drawing of the series, the second drawing includes a human passively riding in the back of a car. The third drawing shows a human actively controlling the car. However, these drawings seem to be not of cars, but rather of trolleys, evinced by the electrical symbols such as 110V, AC, and DC positioned above and below the figures. Unlike ordinary cars, streetcars could appear (especially to children) as if they are moving by themselves. Furthermore, Bettelheim’s interpretation of the second car drawing as Joey’s passive ego is unconvincing if we recognize the fact that there are types of cars and streetcars that are controlled by a driver in the back.

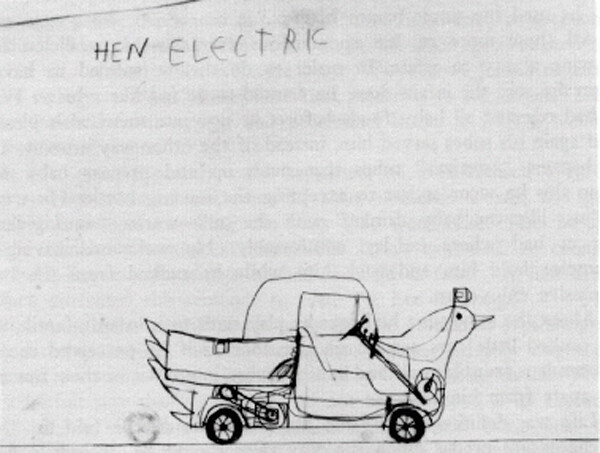

Comparable to Joey’s first (street)car drawing is “Hen Electric,” his drawing of an electric hen that drives itself like a car and which Joey thought had an “electric fetus” in its belly. The first in Joey’s “Carr Family” drawings appears to have more in common with the electrical hen than the other two drawings. Like an animal, it is self-moving and autonomous.

Joey’s “Hen Electric” drawing.

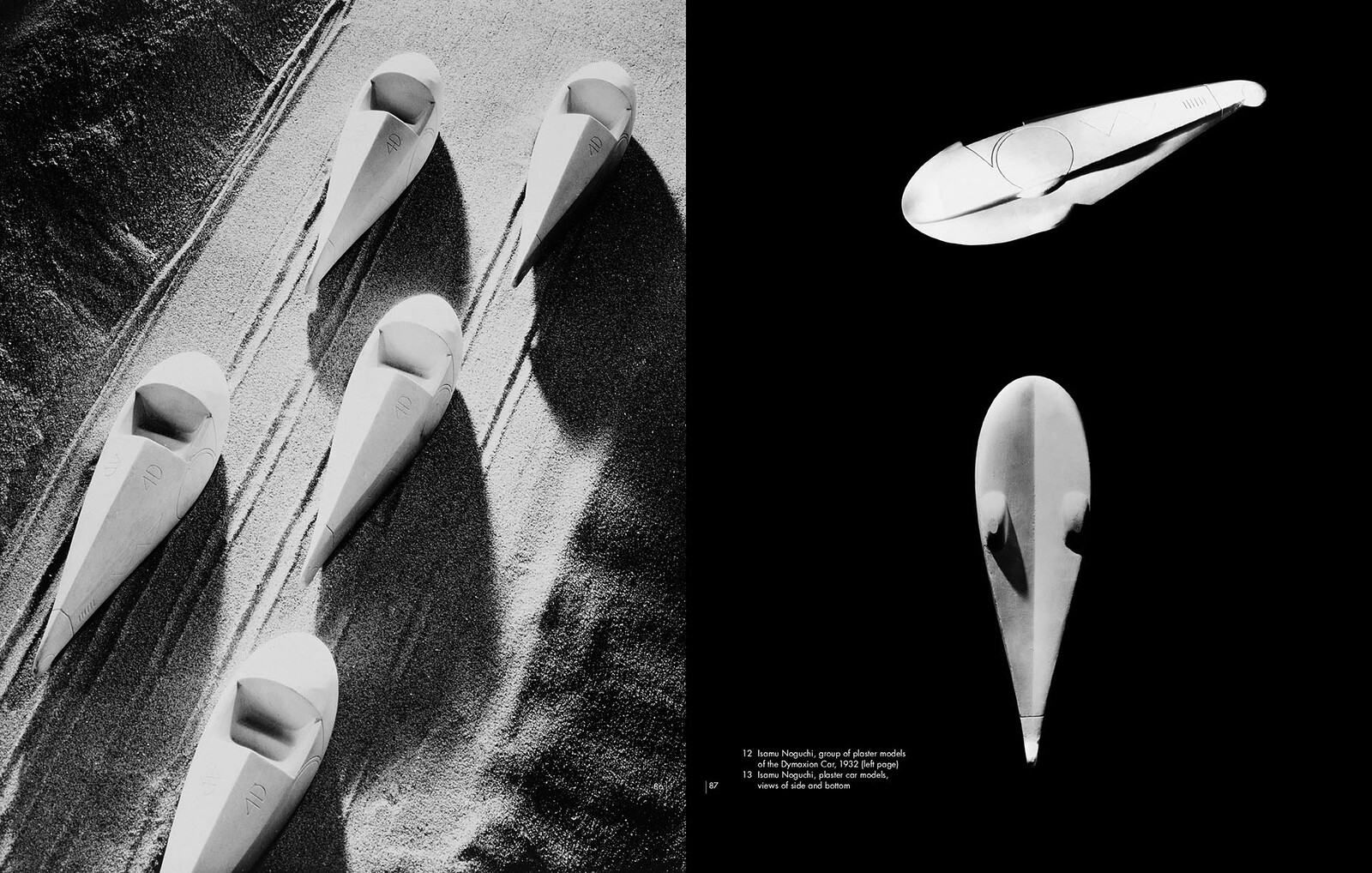

Bettelheim interpreted the third drawing to show that Joey had acquired control over machines and found complete autonomy. But something else appears in the drawing: at the back, there is another piece of mechanical equipment in a box that seems to be drawing power from the streetcar. Depending on one’s perspective, this could also be seen as an animal. Neither Bettelheim nor his critics talk much about this, but Bettelheim did mention that, after seeing an artificial egg incubator at the Museum of Science and Technology, Joey rearranged the tubes that were attached to his bed, pretended that a hen had laid an egg under his desk, and proclaimed that he had laid an egg like a hen, hatched it, and was born again. “I laid myself as an egg, hatched myself, and gave birth to me.” Joey called the third car drawing “hennigan wagon,” which Bettelheim interpreted to mean “hen-I-can,” in other words, “I can (be) hen.” This could be extended to mean “I can lay an egg.” It might then be appropriate to read Joey’s third drawing as an egg incubator powered by electricity to maintain a certain temperature. Egg incubators that children can make at home usually maintain temperature with a light bulb. In Joey’s drawing, the streetcar, the egg incubator—which contains what looks like a light bulb—and the driver are all connected together with wires. If the car Joey drew is a big egg incubator, one could interpret the drawing not to signify autonomy from machines, but the possibility of doing something with them that cannot be done by humans alone.

Bettelheim lived during a time when a cultural understanding of the relationship between humanity and machines was undergoing dramatic changes. “What is entirely new in the machine age,” Bettelheim wrote, “is that often neither savior nor destroyer is cast in man’s image any more. The typical modern delusion is of being run by an influencing machine … Man’s delusions in a machine world seem to be tokens of both our hopes and fears of what machines may do for, or to us.”5 While this might have been the reason why Bettelheim believed Joey to be obsessed with machines, in an interview given three years after he left the alternative school at the University of Chicago, Joey offered a completely different interpretation of his behavior. Answering a question about why he was drawn to machines, Joey said that machines “had wings that rotate” and “were a way to show that [I] had intelligence.” He was “afraid that people would think that [I] was independent” (if he didn’t pretend to be a machine), and he said he “could find many shapes in the shapes the machine parts had.”6 The antagonistic confrontation between humans and machines that Bettelheim identified as the pathological origin of Joey’s condition is evidently absent from Joey’s own thinking. There is unfortunately no record of Joey other than Bettelheim’s analysis, which clearly reflects the naive understanding of machines characteristic of their era. We should instead see Joey as an early, if not radical, pioneer in exploring the potential of what might be possible if humans and machines come together.

Erich Fromm, The Sane Society (New York: Rinehart & Company, Inc., 1955).

Günther Anders and Claude Eatherly, Burning Conscience (New York: Monthly Review Press, 1962). Major Claude Eatherly, whom Anders met and exchanged letters with, was, having dropped the bomb, the “hero of Hiroshima.” Yet after the war, he behaved quite unlike a hero, having attempted suicide, getting arrested for suspicion of theft, and ultimately being diagnosed with schizophrenia. Through his interaction with Eatherly, Anders came to think that his schizophrenia was caused by a fragmented society. It is natural for someone who murdered tens of thousands of civilians by dropping an atomic bomb to suffer from guilt, but American society put him on a pedestal as a hero who brought victory to America. At the same time, there was not a small amount of criticism about the bombing. He was agonized amid these conflicting messages and finally became schizophrenic. According to Anders’s interpretation, the solution that would allow him to escape the role of a gear in the “war machine” was schizophrenia.

Criticism of Bettelheim’s theory started to appear in the mid-1960s. Bernard Rimland, a psychologist, psychiatrist, and a parent to an autistic child, made an effective argument in Infantile Autism (1964) based on his experience and research that autism had no relation with apathetic mothers.

Bruno Bettelheim, “Joey, A ‘Mechanical Boy,’” Scientific American 200 (March 1959).

Bruno Bettelheim, The Empty Fortress: Infantile Autism and the Birth of the Self (Glencoe: Free Press, 1967), 234.

Ibid., 336–37.

Superhumanity is a project by e-flux Architecture at the 3rd Istanbul Design Biennial, produced in cooperation with the Istanbul Design Biennial, the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea, the Govett-Brewster Art Gallery, New Zealand, and the Ernst Schering Foundation.

Category

Superhumanity: Post-Labor, Psychopathology, Plasticity is a collaboration between the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea and e-flux Architecture.