A lot of people say that after they punch a wall they feel a lot better, but their hand is broken.

—David Wojnarowicz1

On June 14, 2017 a fire broke out in a tower block in North Kensington, West London. It quickly spread. The residents’ organization based in the flats had frequently raised safety concerns about the building’s upkeep and maintenance, and expressed anxieties about the poor quality of renovations undertaken there. Their concerns were routinely ignored. The rapid spread of the fire is thought to have been due to the cheap cladding added to the exterior of the building, designed to cut costs but also, it has been speculated, to make cosmetic changes to the building’s appearance so as to make the surrounding area more attractive to prospective property buyers. This was an atrocity that could have been avoided. The local authority’s emergency response to the blaze was also insufficient. Seventy-two people are known to have died in the fire. Though the residents of the building were mostly working-class people living in social housing provided by the council, the tower was located in the Royal Borough on Kensington and Chelsea, one of the richest in the country. The fire starkly and tragically revealed deep structural inequalities—classed and racialized—in British society. The fire was an extreme though by no means isolated example of the brutal consequences of an affluent and callous ruling class more interested in hiding, moving, or ignoring poor people, whose immiseration and exploitation their wealth and status depends upon, than in eliminating or even ameliorating poverty.

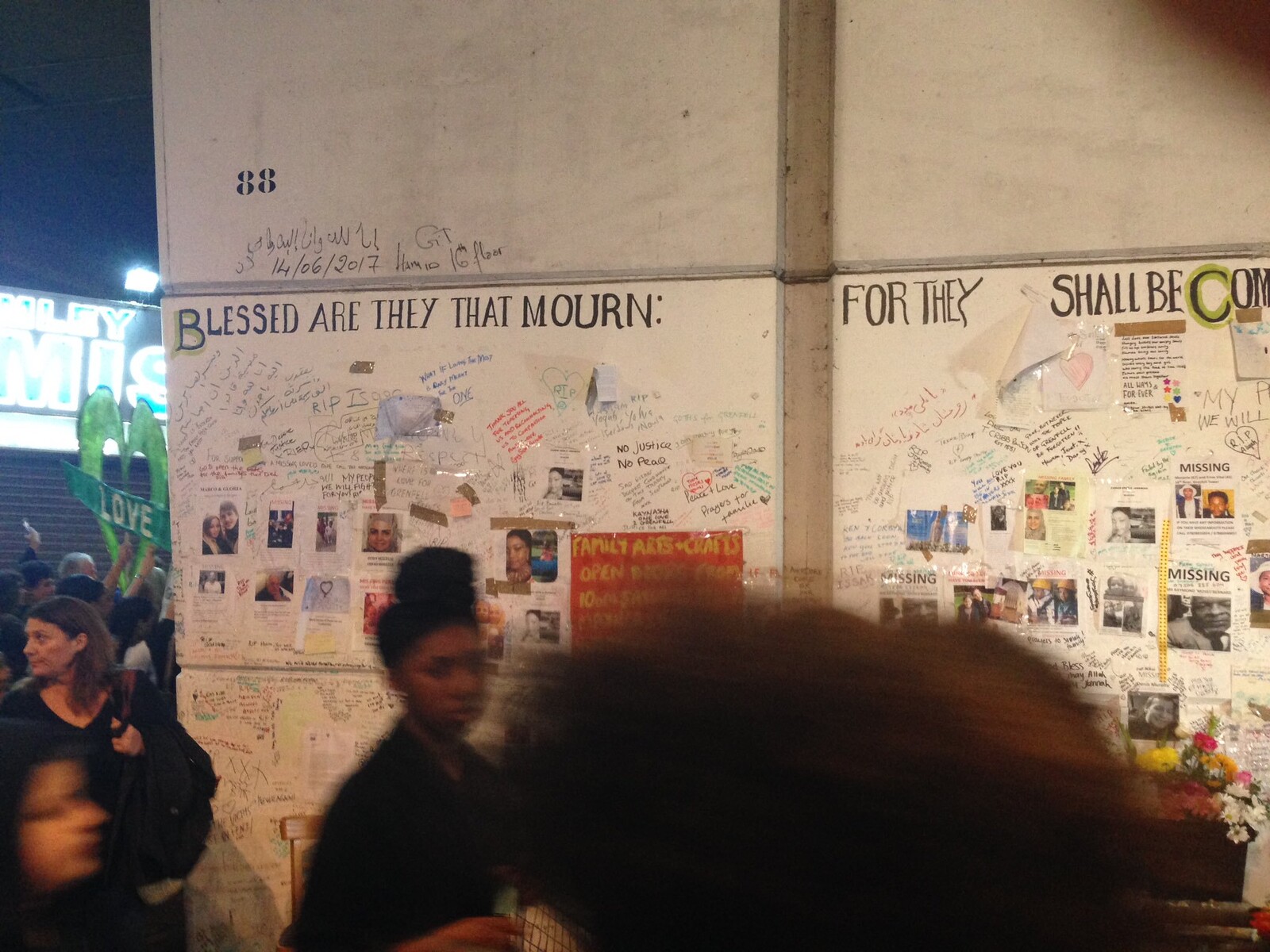

A silent march was held on October 14, 2017, marking four months since the fire took place, protesting the failure of the local council to provide adequate, permanent housing to survivors (and many other failures). On a wall along the march’s path was a sign which reads: “Blessed are they that mourn, for they shall be comforted” (Matthew 5:4). However, the inadequate political response to the crisis and the gross negligence that enabled such a catastrophe to occur in the first place obstruct the process of mourning. The handwritten notes on the walls beneath the sign attest to the difficulty, for survivors and others from the community, of finding any comfort. How to mourn, which implies the possibility of moving on from the original traumatic event, in the face of such glaring social injustice? How to continue the struggle for justice while grieving? How to fight while healing?

In the essay “Paranoid Reading and Reparative Reading” Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick stresses the importance of finding a vocabulary that can “do justice to a wide affective range,” claiming that the term “paranoia” is “a theory of negative affect [which] leaves open the distinctions between or among negative affects.” According to Sedgwick, “a disturbingly large amount of theory seems explicitly to undertake the proliferation of only one affect, or maybe two, of whatever kind—whether ecstasy, sublimity, self-shattering, jouissance, suspicion, abjection, knowingness, horror, grim satisfaction, or righteous indignation.” Her theoretical approach, she contends, is capable of attending to multiple, contradictory, or overdetermined affective states. But before outlining this approach, she caricatures, with her characteristically lacerating wit, various positions that exhibit a reductive approach to affect:

It’s like the old joke: “Comes the revolution comrade, everyone gets to eat roast beef every day.” “But Comrade, I don’t like roast beef.” “Comes the revolution, Comrade, you’ll like roast beef.” Comes the revolution, Comrade, you’ll be tickled pink by those deconstructive jokes; you’ll faint with ennui every minute you’re not smashing the state apparatus; you’ll definitely want hot sex twenty to thirty times a day. You’ll be mournful and militant. You’ll never want to tell Deleuze and Guattari, “Not tonight, dears, I have a headache.”2

Assuming I’m not just being paranoid, among this avalanche of pithy dismissals is a jibe at Douglas Crimp’s 1989 essay “Mourning and Militancy,” a text I have found myself returning to again and again in my attempts to think about how activist communities have responded to forms of psychological damage and developed forms of psychological care within their milieus. Contra Sedgwick’s satirical characterization of his understanding of affect as straightjacketed by a reductive binary, Crimp explicitly claims that a wide range of emotional states accompany political movements and their aftermaths. He is not concerned simply with the seemingly contradictory coupling of mournfulness with militancy, but also in attending to “frustration, anger, rage, and outrage, anxiety, fear and terror, shame and guilt, sadness and despair.”3 Being a mournful militant consists precisely in acknowledging this litany of conflicting emotions.

Following the unexpected death of his father, with whom he’d had a difficult relationship, Crimp recalls that he expressed no sorrow and soon resumed his regular routines. Weeks later, however, he developed a large abscess in his left tear duct which eventually burst, spilling “poison tears” down his face, a symptom he interpreted as a physical manifestation of his repressed grief. “I have never since doubted the force of the unconscious,” he writes, “nor can I doubt that mourning is a psychic process that must be honored.”4 This personal anecdote attesting to the psychic tenacity of unprocessed loss is recounted in the opening pages of his essay, in which Crimp confronts the seemingly oxymoronic relationship between his two eponymous concepts. Writing in the context of the AIDS crisis in the US, and addressing his community of fellow AIDS activists (he was involved with ACT UP in New York), Crimp describes how mourning processes and rituals like candlelit vigils were frequently decried as anathema to militant political struggle—“indulgent, sentimental, defeatist”—by those involved in the movement.5 As people in the gay community lost lovers and friends to the ravages of a devastating illness, the call was to fight for the living, rather than to weep for the dead. But Crimp insists on the necessity of mourning within radical political communities and, more importantly, cautions against the dangers of not mourning. “It is because our impatience with mourning is burdensome for the movement that I am seeking to understand it,” he writes.6

Crimp acknowledges that mourning, as canonically defined in 1917 by Freud in “Mourning and Melancholia,” does indeed seem incompatible with political activism. For Freud, though a finite process, mourning is all-consuming—it “leaves nothing over for other purposes or other interests.”7 Crimp frames his argument in relation to Freud’s outline of the concept of mourning, but nonetheless acknowledges that “normal” mourning in Freud’s sense is impossible within the context he is describing.8 According to Crimp, Freud’s theory says very little about communal grieving rituals, nor does it address the possibility that such rituals could be socially obstructed.9 “Reality-testing” is central to Freud’s discussion of mourning, through which the subject comes to acknowledge and eventually accept the loss of the loved object, consequently withdrawing or detaching their libido from it. But “reality” was not a neutral empirical backdrop in the context of the AIDS crisis because of American society’s “ruthless interference with bereavement” and because loss was not a fact of the past to come to terms with and move on from but remained a possibility for the future—“whether we share this fate is so unsure.”10 In the face of “social and political barbarism” and the enforced silencing of grief within a hostile, homophobic and callous society, Crimp declares that “mourning becomes militancy.”11 Except his argument doesn’t end there. Though sympathetic to the transformation of sorrow into anger, he claims that because this process only takes place on a conscious level, it leaves unconscious antagonisms unresolved. Militancy cannot function as a substitute for mourning but instead results from the socially enforced disavowal of grief; poison tears remain unwept. In this sense, militancy represses mourning.

Crimp complicates and reconceptualizes Freud’s definition of mourning by calling into question the notion that mourning can be accomplished by deferring to reality. Instead, he insists that the subject must engage in a process of attempting to survive within the external world without accepting it, while also being attentive to the damaging qualities of internal unconscious processes. In this (re)definition, mourning no longer entails a “respect for reality,” as Freud outlined, but involves interrogating and reconfiguring both external and internal realities.12 Crimp also implicitly challenges Freud’s statement that in mourning “there is nothing about the loss that is unconscious”;13 but though Crimp identifies a certain melancholic self-doubting disposition in the AIDS activist community, he refuses to follow Freud in defining melancholia as pathological nor does he claim that this affective state results from a melancholic (and hence fully unconscious) relationship to the lost object.14 Crimp’s understanding of militant mourning is thus distinct from both (normal) mourning and (pathological) melancholia as defined by Freud.

Sarah Schulman’s 2012 book Gentrification of the Mind seeks to redress the absence of a public conversation about the consequences of AIDS in America and overcome the pervasive social amnesia that persists about the scale and impact of mass death. She writes: “Every gay person walking around who lived in New York or San Francisco in the 1980s and early 1990s is a survivor of devastation and carries with them the faces, fading names, and corpses of the otherwise forgotten dead.”15 Schulman contrasts the “barely mentioned” 81,542 people known to have died of AIDS in New York City as of August 2008 with the 2,742 people killed on 9/11, whose deaths have been officially memorialized through national mourning rituals and commemorative sites.16 Her fury is not only directed at the forgetting of the dead but, moreover, at the forgetting of the neglect of politicians who have never been held accountable for their actions which enabled the crisis to reach such a devastating scale: “The names of our friends whom Ronald Reagan murdered are not engraved in a tower of black marble.”17 Crimp similarly discusses the “gross political negligence” that contributed to exacerbating the AIDS epidemic, and addresses the psychic damage inflicted by a homophobic society which delegitimized experiences of bereavement and “blamed, belittled, excluded, derided” the gay community rather than offering empathy, support, or adequate health care (here the parallel with the aftermath of the Grenfell Tower fire is most apparent).18

Despite identifying brutal governmental policies and negligent social practices, Crimp nonetheless warns against carving too neat a dichotomy between the external and the internal, the social and the psychological. Yes, he says, the world is violent and unjust and this must be combated. However, violence is not only located outside the subject in a hostile society but also operates on an internal, unconscious level. No single line can be plotted that moves inexorably from external violence (cause) to internal misery (effect). Instead, suffering might better be understood as resulting from ongoing conflicts between the social and the psychological which are always mutually constituted and whose origins are never located in a single time or place: “Violence is also self-inflicted.”19 For Crimp, focusing solely on transforming the external world through militant action does nothing to resolve the corrosive effects of unconscious processes. After all, whatever activism might succeed in achieving, nothing can ever undo the original traumatic events. Here he cites Jacqueline Rose’s discussion of a disagreement between Freud and Wilhelm Reich concerning the origins of misery, which echoes a passage in Sexuality in the Field of Vision (1986) where she identifies a long-standing tendency for left-wing theorists seeking to politicize psychoanalysis to imagine that a clean distinction can be made between psychic and social processes (and which thus dispenses with the unconscious in the process):20

Historically, whenever the political argument is made for psychoanalysis, this dynamic is polarized into a crude opposition between inside and outside—a radical Freudianism always having to argue that the social produces the misery of the psychic in a one-way process, which utterly divests the psychic of its own mechanisms and drives.21

Following Rose’s insights, Crimp insists that locating all negative feelings in the external world only serves to compound psychological antagonisms and experiences of suffering: “By making all violence external, we fail to confront ourselves, to acknowledge our ambivalence, to comprehend that our misery is also self-inflicted.”22 As such, Crimp insists that activists should be able to acknowledge feelings of “frustration, anger, rage, and outrage, anxiety, fear, and terror, shame and guilt, sadness and despair” (to repeat the list cited above) and also attend to the experiences of those “who feel only a deadening numbness or constant depression … who are paralyzed with fear, filled with remorse, or overcome with guilt”—those for whom coherent expressions of anger in the form of explicit political action may be impossible.23 This, however, entails a more expansive understanding of militancy rather than a rejection of it. Caring for remorseful and withdrawn friends and comrades is a form of political practice that should not displace but be combined with other more public or combative forms of resistance.

Crimp concludes his essay with a demand for a militancy that acknowledges the necessity of mourning:

The fact that our militancy may be a means of dangerous denial in no way suggests that activism is unwarranted. There is no question but that we must fight the unspeakable violence we incur from the society in which we find ourselves. But if we understand that violence is able to reap its horrible rewards through the very psychic mechanisms that make us part of this society, then we may also be able to recognize—along with our rage—our terror, our guilt, and our profound sadness. Militancy, of course, then, but mourning too: mourning and militancy.24

Crimp’s use of the conjunction “and” in the essay’s title and in this closing line risks suggesting that mourning and militancy are distinct but parallel processes, whereas the essay “Mourning and Militancy” actually reconceptualizes both terms. It concludes by advocating a kind of mournful militancy, a militancy that can be expressed in numerous affective registers—grief and anger, care and sadness, collectivity and withdrawal—and one which attends to psychic wounds while simultaneously attempting to radically transform society.

Epilogue

Few political movements have contended with death in an analogous manner to the activism that responded to the AIDS crisis, but Crimp’s argument is nonetheless useful for thinking about a tendency for piety and moralism within other activist milieus. Indeed, Crimp makes this connection himself, citing the famous phrase of labor organizer Joe Hill: “Don’t mourn! Organize!”25 He clearly outlines a recurrent tendency within radical political movements to dismiss negative emotions as detrimental to a collective cause, and to characterize anxiety, suffering, despair, and introspection as self-indulgent and apolitical. Yet the fact of this recurrence, which recalls what Freud describes as “laments which always sound the same and wearisome in their monotony,” suggests that such experiences persist and need to be acknowledged.26 Following Freud, Crimp is also explicit that the mourning processes he is considering do not solely apply to the literal dead but also to the death of ideals (in his case the death of the promise of uninhibited sexual expression). It is this latter form of mourning that might be most generatively thought in relation to the aftermath of other historical moments or movements (although, of course, actual corpses—often those of people killed at the hands of the state—are not absent from other struggles). Assuming people’s political ideals are not crushed along with their movements, the immediate past of defeat is not only something to be worked through and left behind, but memories of solidarity and shared conviction might also give hope and even shape to the future.

In Simone Weil’s Gravity and Grace, a book which was compiled posthumously by a priest named Gustave Thibon with whom she was friends and to whom she had entrusted her notes, Thibon mentions the biblical passage scrawled on the wall near the site of the Grenfell Tower fire: “Blessed are they that mourn: for they shall be comforted.” In a footnote to Weil’s text, Thibon expresses concern that her pronouncement seems to disagree with the bible. She writes:

Human misery would be intolerable if it were not diluted in time. We have to prevent it from being diluted in order that it should be intolerable. “And when they had had their fill of tears” (Iliad).—This is another way of making the worst suffering bearable. We must not weep so that we may not be comforted.27

Weil is asserting that so long as suffering exists, individual consolation or amelioration is impossible; mourning processes should not be completed as long as injustice is ongoing. For Weil, weeping implies acceptance. Mourning dilutes injustice. Weil’s position is uncompromising. She insisted on the possibility of entering fully into the experiences and sufferings of other people, but as Anne Carson observes: “It is hard to commend moral extremism of the kind that took Simone Weil to death at the age of thirty-four; saintliness is an eruption of the absolute into ordinary history and we resent that.”28 Crimp’s essay, on the other hand, refuses the absolute and instead attempts to find a way to continue living—to find a way to weep that might provide comfort without diluting the demand to end suffering. The situation is intolerable but we need to find ways to mourn within it if we ever hope to destroy it. Mourning, of course, then, but militancy too: mournful militancy.

David Wojnarowicz, Close to the Knives: A Memoir of Disintegration (New York: Vintage Books, 1991), 203.

Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick, “Paranoid Reading and Reparative Reading, or, You’re so Paranoid, You Probably Think this Essay is About You,” in Touching Feeling: Affect, Pedagogy, Performativity (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2003), 123–151.

Douglas Crimp, “Mourning and Militancy,” October 51 (1989): 3–18, 16.

Ibid., 4–5.

Ibid., 5.

Ibid., 10.

Sigmund Freud, “Mourning and Melancholia,” Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, vol. 14 (1914–1916), ed. and trans. James Strachey et al. (London: Hogarth Press), 243–58, 244.

Here Crimp contrasts his approach to that taken by Michael Moon in “Memorial Rags,” which proposes to read mourning through the lens of fetishism. Moon rejects Freud’s definition of mourning for being too individualized and normative but his concluding reading of Walt Whitman’s “The Wound-Dresser” is not ultimately incompatible with Crimp’s analysis. See Michael Moon, “Memorial Rags,” in Professions of Desire in Literature: Lesbian and Gay Studies in Literature, eds. George E. Haggerty and Bonnie Zimmerman (New York: Modern Language Association of America, 1995), 233–40.

Crimp, 7.

Ibid., 8–9.

Ibid., 10, 9.

Freud, 245.

Ibid.

Crimp argues that a certain “moralizing self-abasement” within the gay community has something in common with Freud’s description of the egoistic melancholic (12).

Sarah Schulman, The Gentrification of the Mind: Witness to a Lost Imagination (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2012), 45.

Ibid., 46.

Ibid., 48. Schulman also gives the example of Jesse Helms, a homophobic senator from North Carolina who argued on moral grounds that money should not be spent on helping people with AIDS. On the “state-condoned violence and murder” enabled by politicians like Reagan and Helms, see also David Wojnarowicz, “Do Not Doubt the Dangerousness of the 12-Inch Politician,” Close to the Knives, 138–64, 148.

Crimp, “Mourning and Militancy,” 15.

Ibid., 16.

Of course, people involved in AIDS activism were not necessarily on the left. As Leo Bersani famously notes: “To want sex with another man is not exactly a credential for political radicalism—a fact both recognized and denied by the gay liberation movement.” See Bersani, “Is the rectum a grave?,” October 43 (1987): 197–222, 205. The question of the relationship between American communism and gay liberation struggles is central to Tony Kushner’s 1991 play Angels in America: A Gay Fantasia on National Themes, which includes a fictionalized version of Roy Cohn, the infamous McCarthy-era lawyer who acted as prosecutor in the trial of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg, and who was a closeted homosexual. He died of AIDS in 1986.

Jacqueline Rose, Sexuality in the Field of Vision (London; Verso, 1986), 10.

Crimp, “Mourning and Militancy,” 17.

Ibid., 16.

Ibid., 18.

Ibid., 5.

Freud, 256.

Simone Weil, Gravity and Grace, trans. Emma Crawford and Mario von der Ruhr (London: Routledge, 2002) 14.

Anne Carson, “Decreation: How Women Like Sappho, Marguerite Porete, and Simone Weil Tell God,” Common Knowledge 8, no. 1 (2002): 188–203, 203. I write in more detail about Weil in “Rub it Better Til It Bleeds,” How to Sleep Faster #7 (London: Arcadia Missa, 2017).

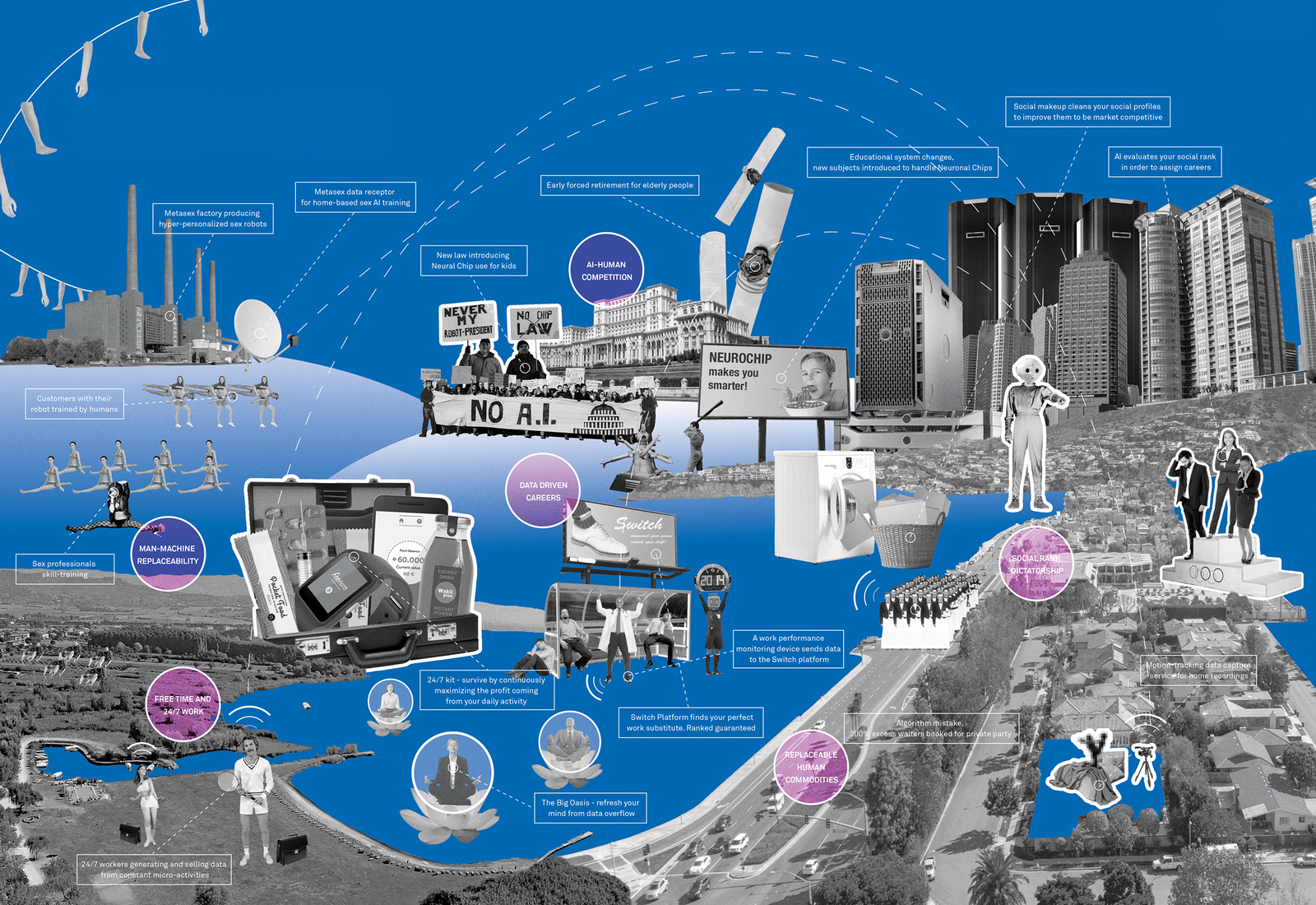

Superhumanity is a project by e-flux Architecture at the 3rd Istanbul Design Biennial, produced in cooperation with the Istanbul Design Biennial, the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea, the Govett-Brewster Art Gallery, New Zealand, and the Ernst Schering Foundation.

Category

Superhumanity: Post-Labor, Psychopathology, Plasticity is a collaboration between the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea and e-flux Architecture.