Death is a plastic force. Operating through communication channels and grounded in a culture of image sharing, domestic spin-off technologies in which death is embedded have engendered a new human body: one that contains within itself ceremonies for the deceased and counterpart sites for a new type of cemetery. These memorials are embedded in modifications of the body itself as auto-performative ritual. In a reflexive mode, this instrumentalization of death and its memorial-body shapes and is shaped by architectural contexts of domesticity, introducing a series of unique spatial consequences such as typological twinning, programmatic promiscuity, and physiological transmutations in otherwise ordinary sites like the bathtub, the living room, and the bedroom.

Upon Whitney Houston’s death, Bobbi Kristina Brown inherited the entirety of her mother’s estate. She came to own her wardrobe, furniture, property, and personal effects. One month following the death, Bobbi Kristina told Oprah Winfrey that the morning after her mother’s body was discovered, she moved back into Houston’s Atlanta home, having felt encouraged to do so in communion with her mother’s spirit. “I have to carry on the legacy. We’re going to do the singing thing. Some acting, some dancing.”1 Three years and four months after her mother’s own drug-induced drowning, Bobbi Kristina was found face down in a bathtub. Where Whitney’s death—at age forty-eight, in the bathroom of suite 434 of the Beverly Hilton Hotel—had been deemed an accidental drowning aided by the effects of atherosclerotic heart disease and the use of cocaine, Bobbi Kristina’s was suspected to be a deliberate act, restaging her mother’s demise in the bathtub.

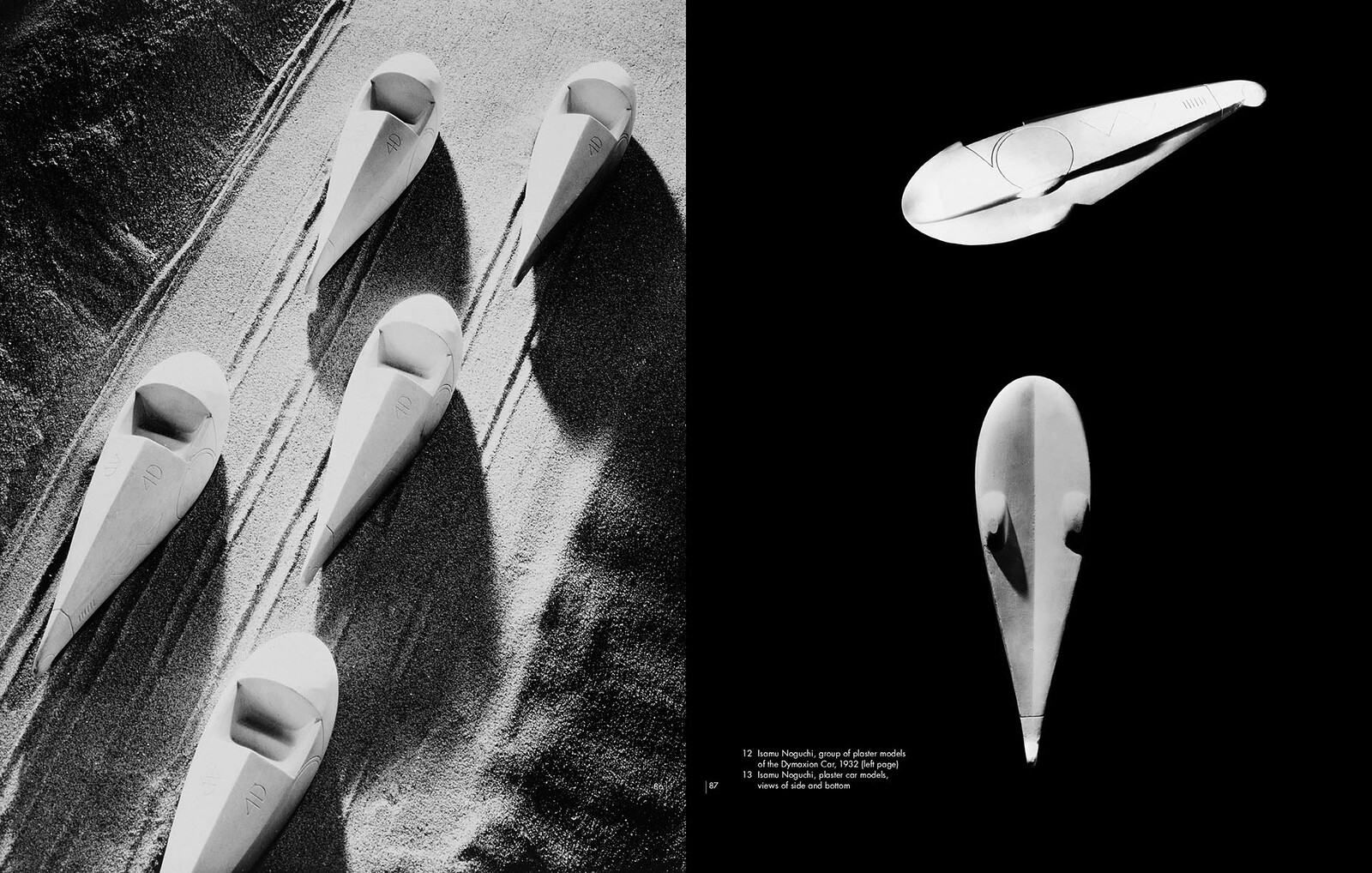

Gottfried Semper, musing on the idea of plasticity, observes that “our language lacks a general and comprehensive expression for all the arts whose common material basis or primeval material … is potter’s clay—that is, those arts whose common primeval technique consists of giving form and shape to a plastic soft paste.”2 After Whitney’s death, Bobbi Kristina’s life can be understood as a period of self-fluidity, a plastic remodeling into her mother’s image. Bobbi Kristina’s suicide and the reignition of the media zeitgeist that would ensue is her ultimate attempt to confirm herself as an extended memorial to the maternal pop star: as sacrificial tribute and twin event.

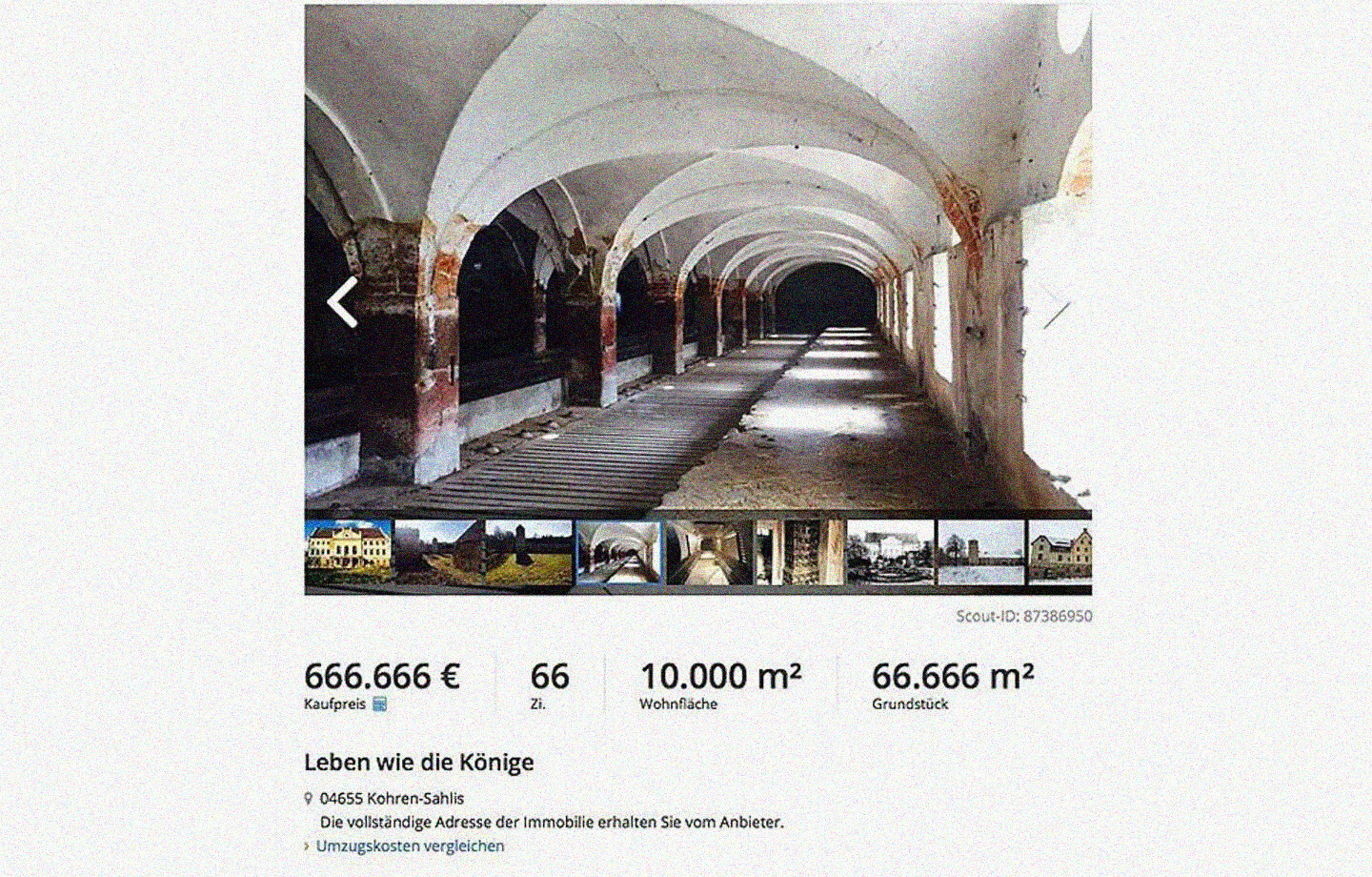

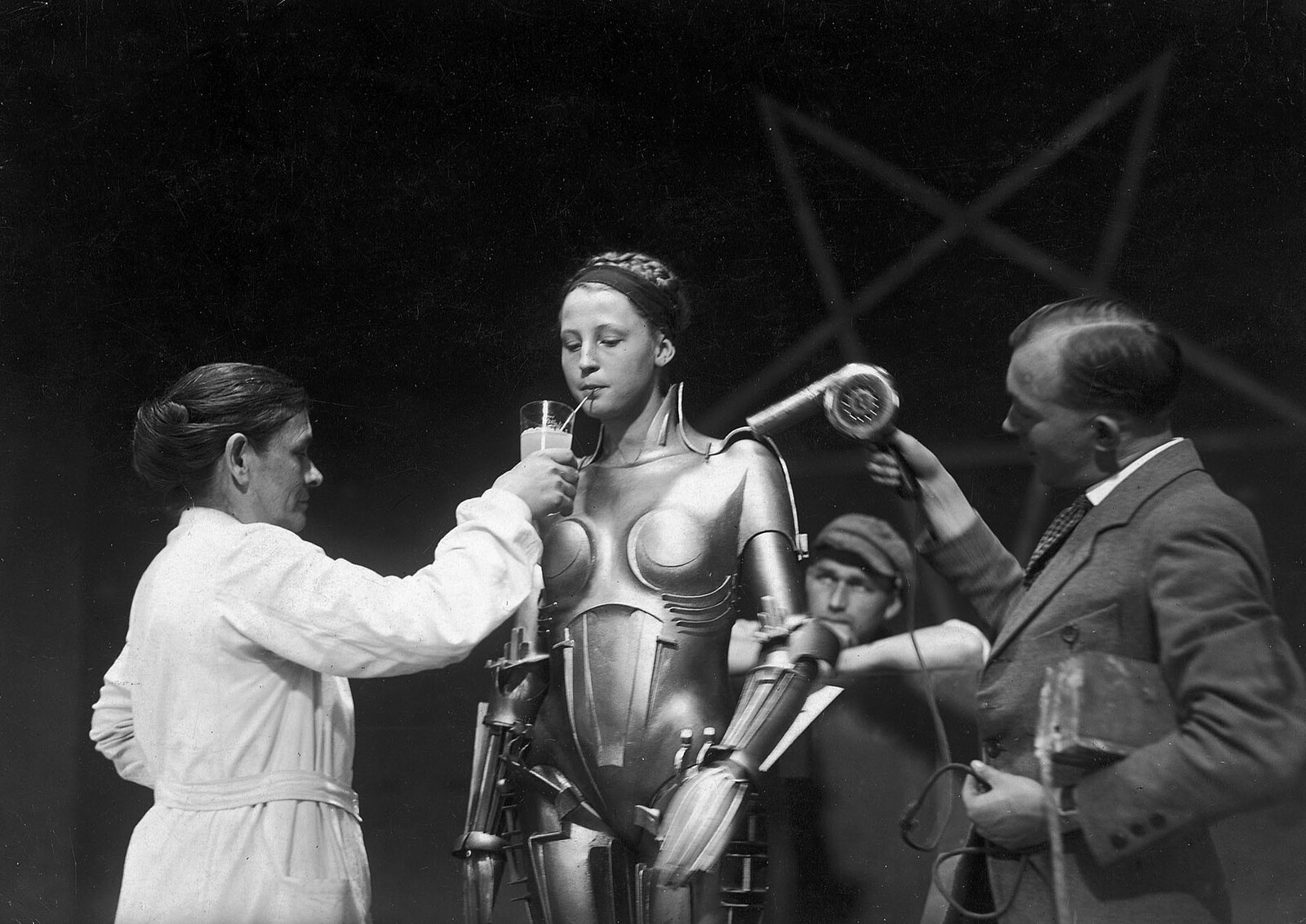

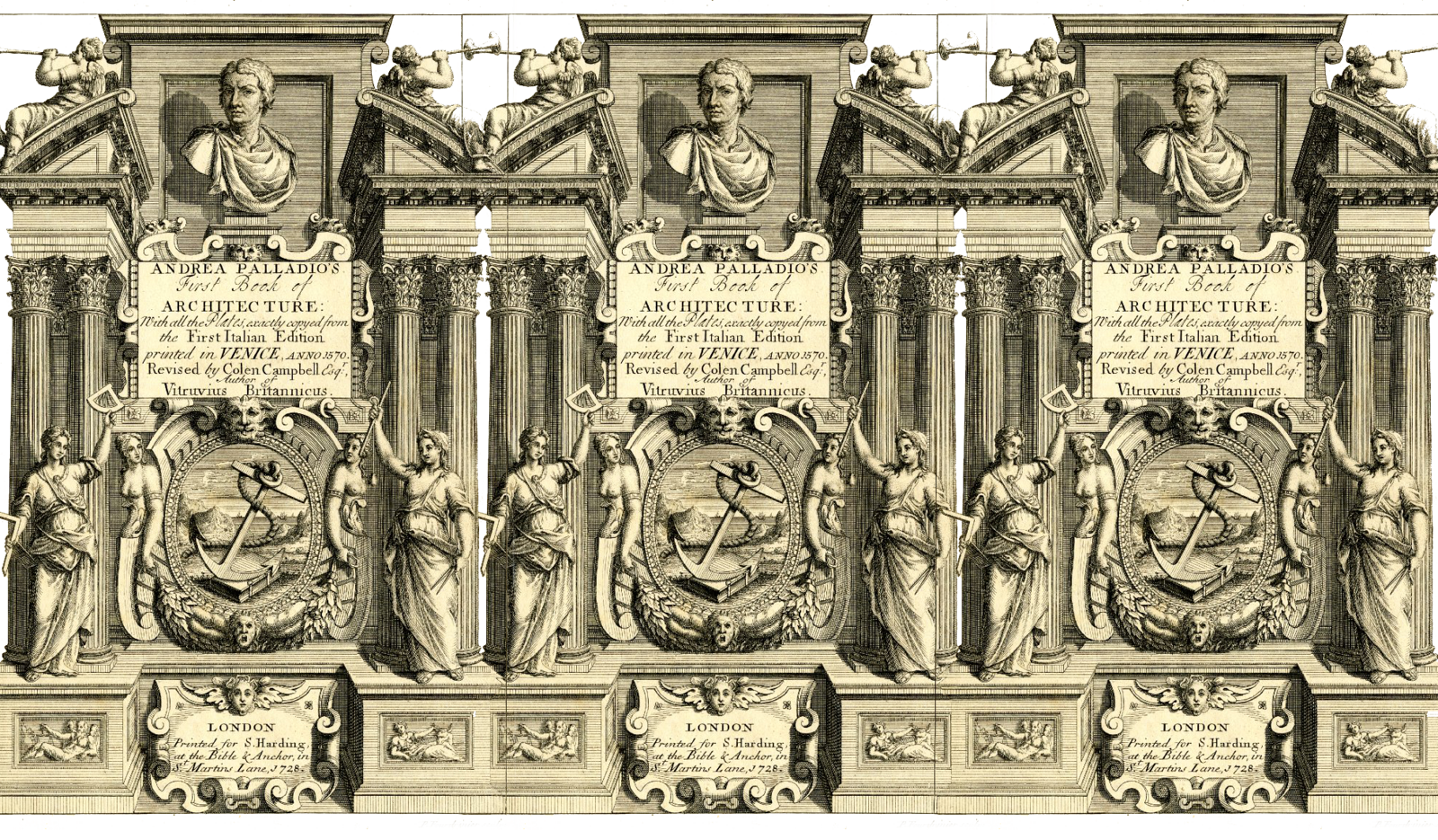

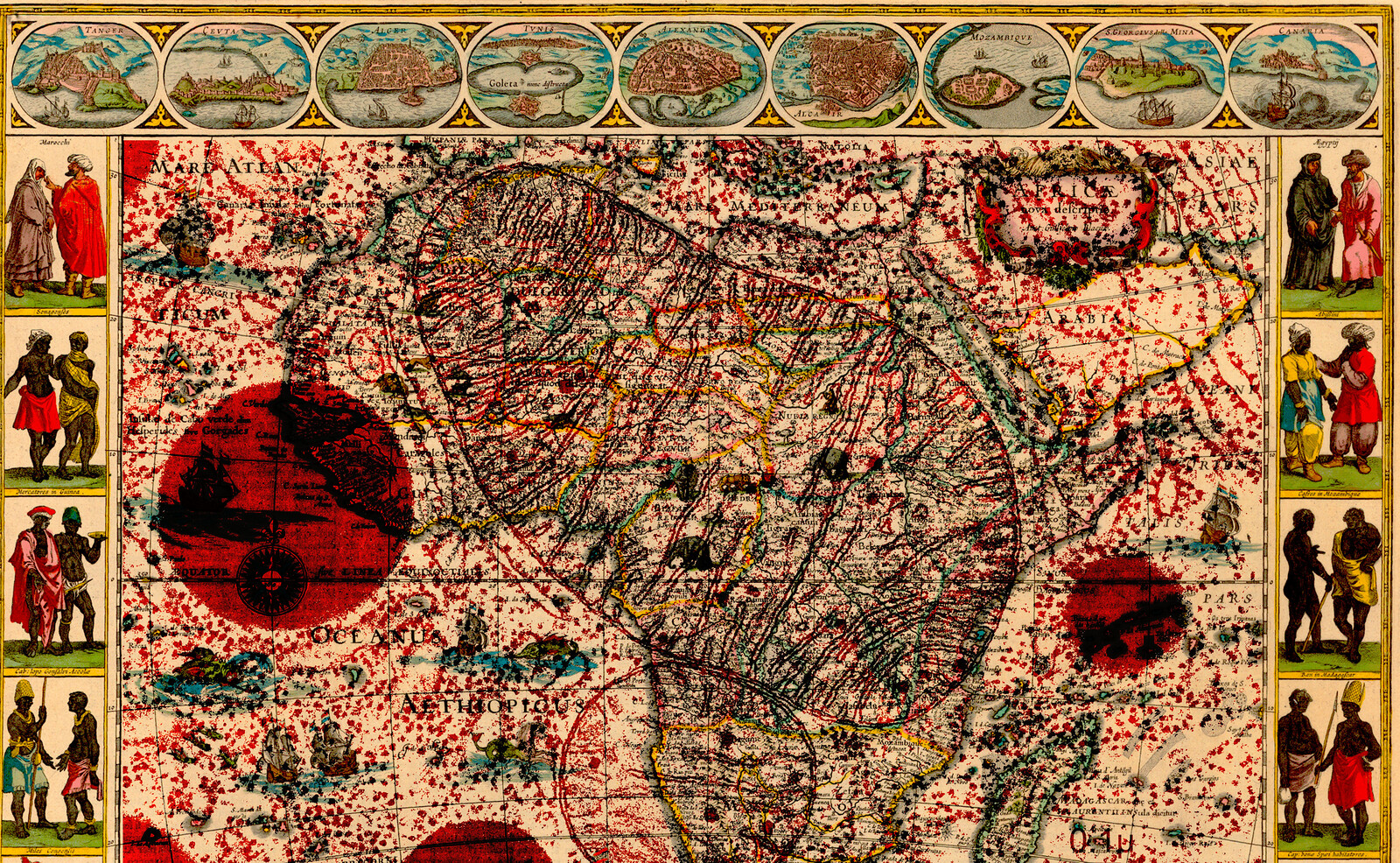

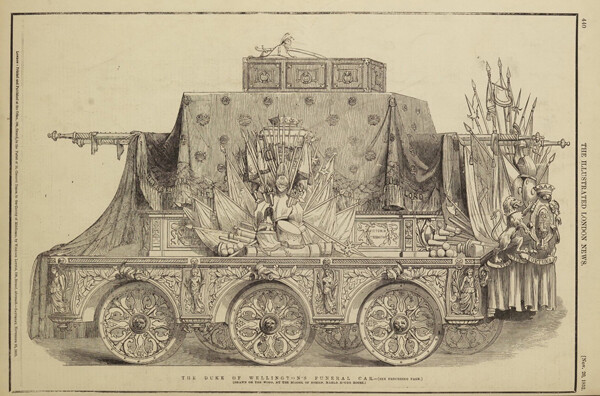

Gottfried Semper, The Duke of Wellington’s Funeral Car, originally published in The Illustrated London News, November 20, 1852.

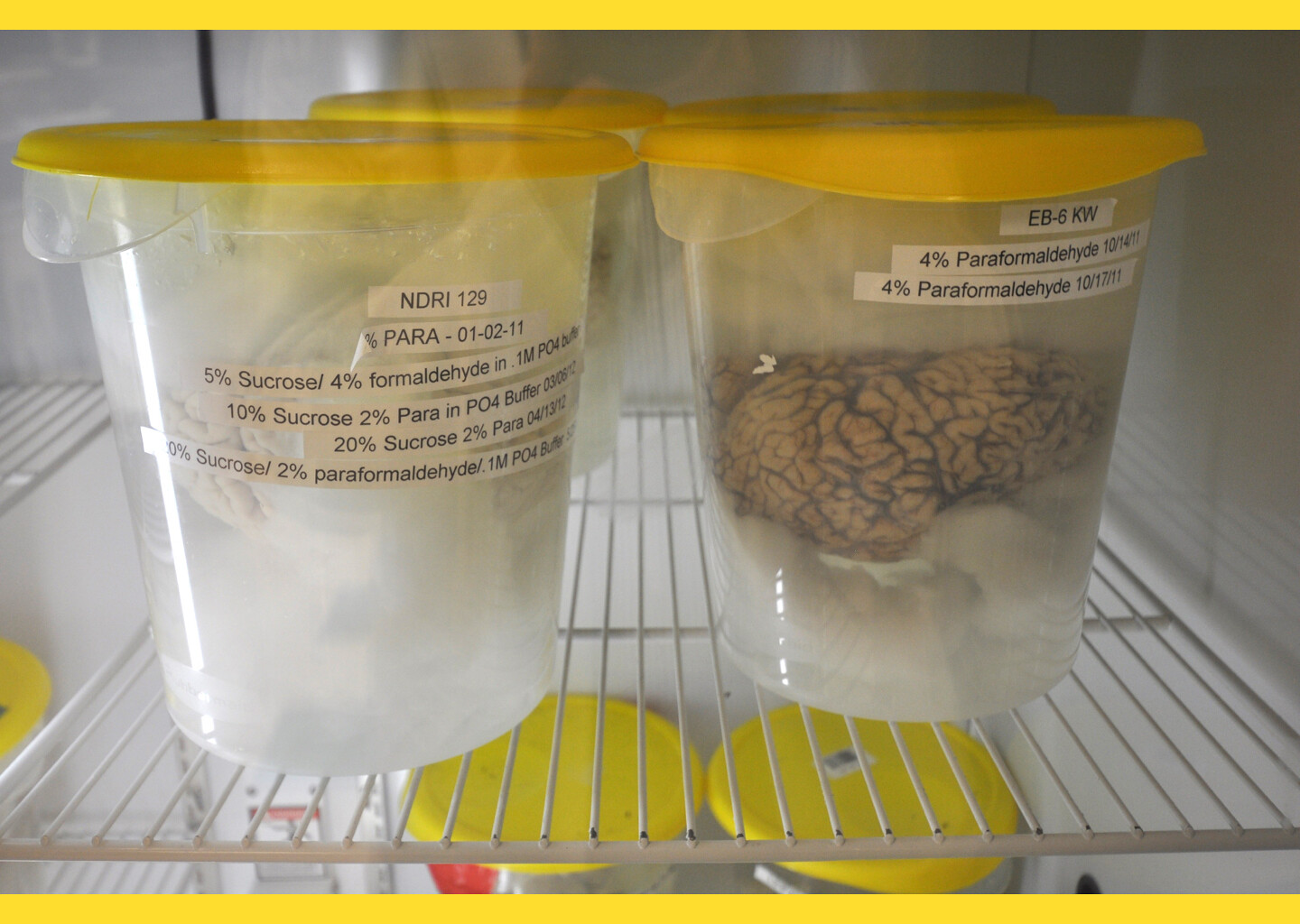

Clay takes precedence in Semper’s understanding of the plastic process of form-making because clay “was the first material to be used for this technique … and because clay, as the first plastic material, to some extent established the style to be followed for other materials later.”3 Clay thus stands in for any material substance conducive to shaping in a “soft” state. In this sense, we could understand the design of human bodies—Bobbi Kristina’s included—as an analogous mode of plastic design. Unlike Semper’s pottery, the design of the human in the face of death never culminates in a fixed instantiation, but rather functions in a state of constant fluidity. Bobbi Kristina’s body continued to evolve past her immersion in the tub: first as a semi-resuscitated organism on hospital life support, then as a cadaver in fluid processing in the embalming chamber of a funeral home, next as a cosmetically enhanced corpse in an open-casket funeral, then finally as an image circulated again and again in print and on online tabloid sites.

Nonetheless, Semper’s consideration of death remains compelling. He claims the plastic practice of ceramics as one of “vessel making,” and points to the reciprocal origins of both the tub and sarcophagus and the urn and the canopic vase, claiming them as simultaneously archetypal instruments of death, ritual, sustenance, and hygiene. And indeed, in the final act before her biological expiration, Bobbi Kristina recast her bathtub as a sarcophagus, just as Whitney did. Healing and decay—or the reconstruction of the body of the living and the extension of death—lie on a fluid scale and inhabit the same artifacts, spaces, and technologies. All this places these trans-biological instruments, extending between the living and nonliving, into the domestic realm. Bobbi Kristina’s hygienic sarcophagus, like her mother’s, was provided by a uniquely domestic architecture. Furthermore, Bobbi Kristina’s extended memorial to her mother—the adoption of her properties, the ambitions to mimic her career, and the rehearsal of her death from three years prior—required an architecture of domesticity and the personal effects it housed.

In Facebook’s first significant encounter with death, we can observe a related case of extended memorial via body transformation facilitated by an architecture of domesticity. John Berlin was a middle-aged, overweight, married father of three living in a trailer home in Arnold, Missouri. On January 28, 2012, his twenty-one-year-old son Jesse died unexpectedly of unknown causes in his sleep. That same year, John Berlin started a YouTube channel and began posting videos of day-to-day activities, many featuring his kids. Experiments with Traffic Control (“Just another day at work,” Feb. 15, 2012, now 305 views), Trippy Cat (“She’s cool man, she just kinda trippy,” July 23, 2012, now 1,189 views), and Rubber Face (“Just me and a leaf blower,” Oct. 22, 2012, now 6,602 views) documented the months following Jesse’s death and the subtle ways in which it started to mobilize changes around the Berlin family home.

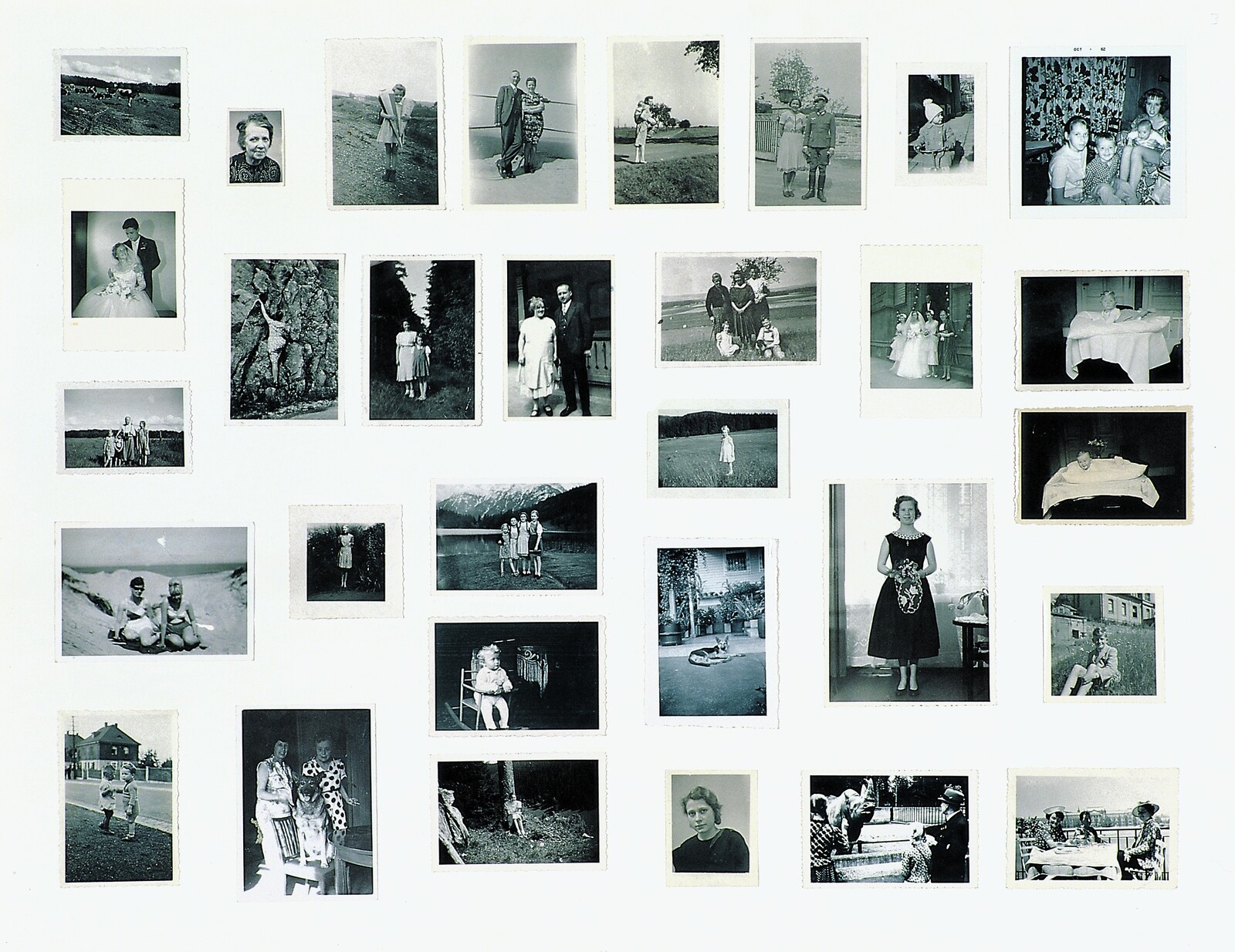

Common Accounts, John Berlin’s Trailer Home in Transition, 2012–2014, 2017.

A few months after Jesse’s death, John discovered the Insanity physical fitness program, developed by Santa Monica–based Beachbody LLC. Confronted with death, Berlin turned to exercise to reverse the effects that a sedentary lifestyle had had on his forty-four-year-old body. On September 15, 2013, John posted his first fitness-oriented video, showing him competing in an obstacle course race. One month later, he began posting videos of Insanity workouts in his trailer home living room (now 5,344 views). By December, he announced he was taking on clients as a trainer in that same living room (now 21,809 views), now outfitted with an ad hoc memorial to his son, Jesse, on the room’s back wall.

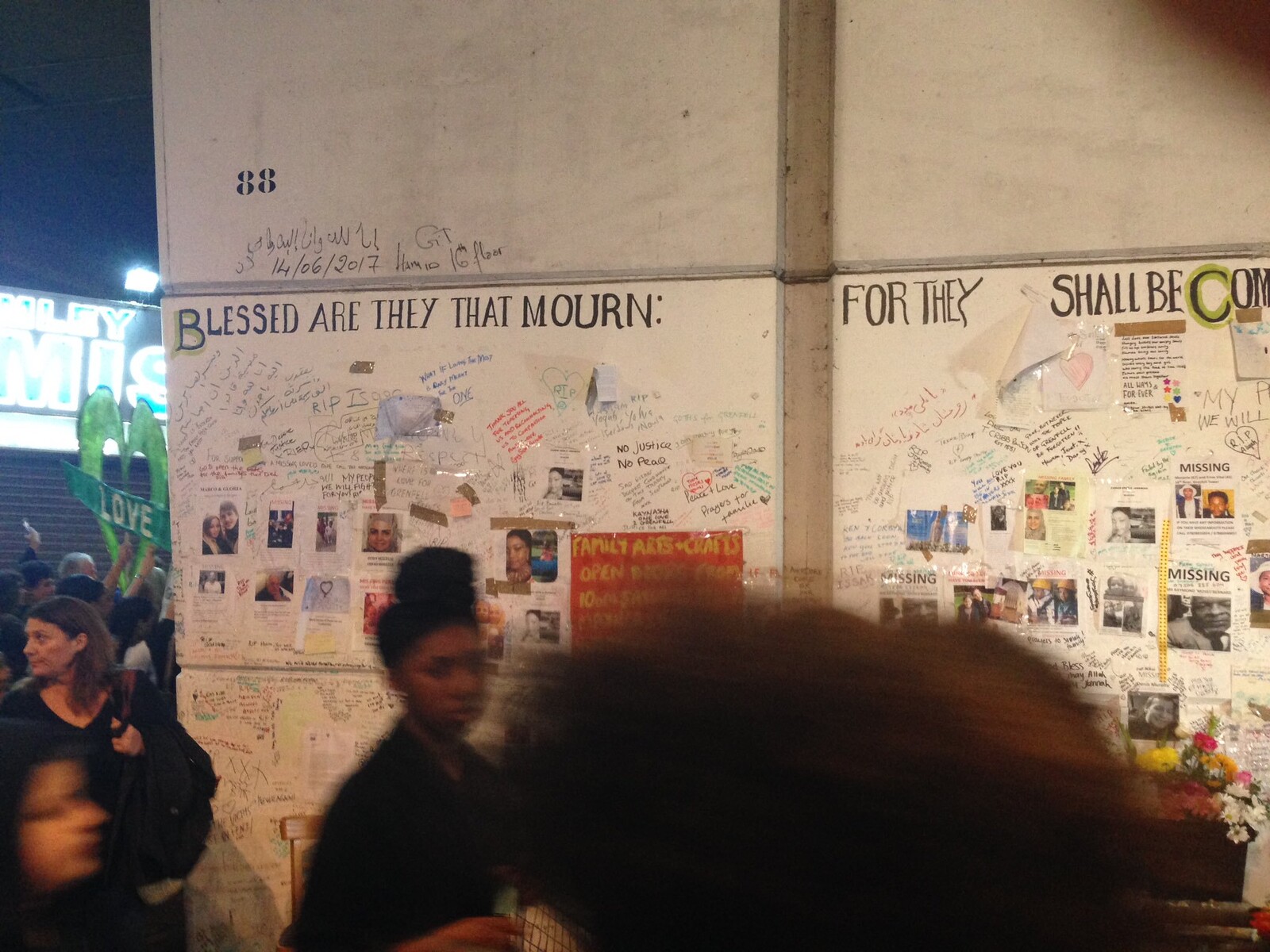

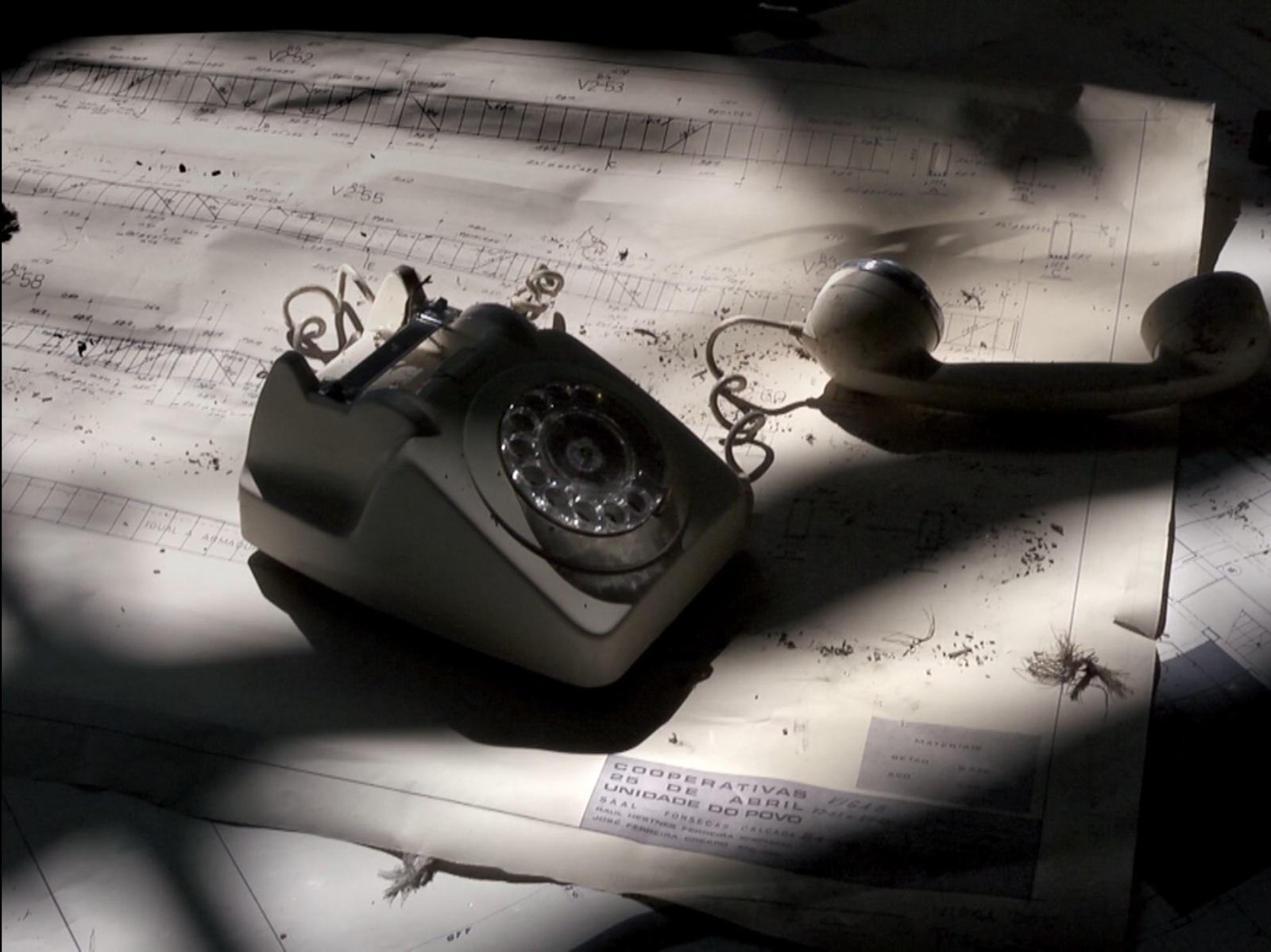

Two years after his son’s death, John posts his first viral video, in which he makes a plea to Facebook for a “Look Back” video of his dead son’s account. The Look Back video format, a slideshow of greatest hits from a user’s virtual material, was a result of Facebook’s tenth anniversary celebrations. An emotional Berlin wanted Facebook to generate such a video from the material he didn’t have access to on his son’s account and share it with him. After logging two million YouTube views in a couple of days, Berlin received a call from Mark Zuckerberg, granting his request and announcing an immediate review of Facebook’s policies toward memorialization and the accounts of dead users.

In the background of the plea video (now 3,051,927 views, 59,884 likes, 646 dislikes), Berlin’s living room had been further transformed. His son’s memorial wall was replaced by floor-to-ceiling mirrors, revealing sports equipment behind the camera and confirming the space as a gym—and Berlin as a trainer. The viewer, in turn, became a participant in Berlin’s mourning. Berlin’s Facebook page and his YouTube video comment feeds came to operate as a social platform for others to commiserate and mourn their own deaths. Among the virtual crowd of well-wishers, supporters, and sympathizers, YouTube user sunrise1965 wrote, “I am so sorry for your loss. I think that you will get your wish for a beautiful memory of your son. My brother died a few months ago, suddenly and I look at his photos on facebook every day. It is a way to feel close, to see parts of his life that were so important to him.”

Berlin’s bodily transformation mirrors the programmatic promiscuity of his living room, both of which served as acts of memorialization. Death has long since moved beyond the cemetery, and new opportunities in remains disposal, ceremonial protocols, and the prospect of a virtual afterlife demand collective attention. Death is perhaps most evident today online, where a lack of design regularly lets death come to the fore in ways that are increasingly unresolved for the living. The fluidity of the body between material and digital domains fosters its own self-reflexive agency. Yet in order for a body to operate in the afterlife, participation in the sociopolitical systems of the living is needed and only granted through mundane and bureaucratic mechanisms. The afterlife endures as long as it efficiently replicates and remains present among the structuring conditions of the living. The dead bear importance within spaces of social and political engagement through channels and platforms identical to the ones inhabited by the living. Thus, the deceased can only be eternally ceremonialized as long as they are able to occupy and transform real estate, virtual estate, and the human body, and if they remain culturally and financially productive. The extension of death into life can only persist as long as the defunct body is able to mobilize value.

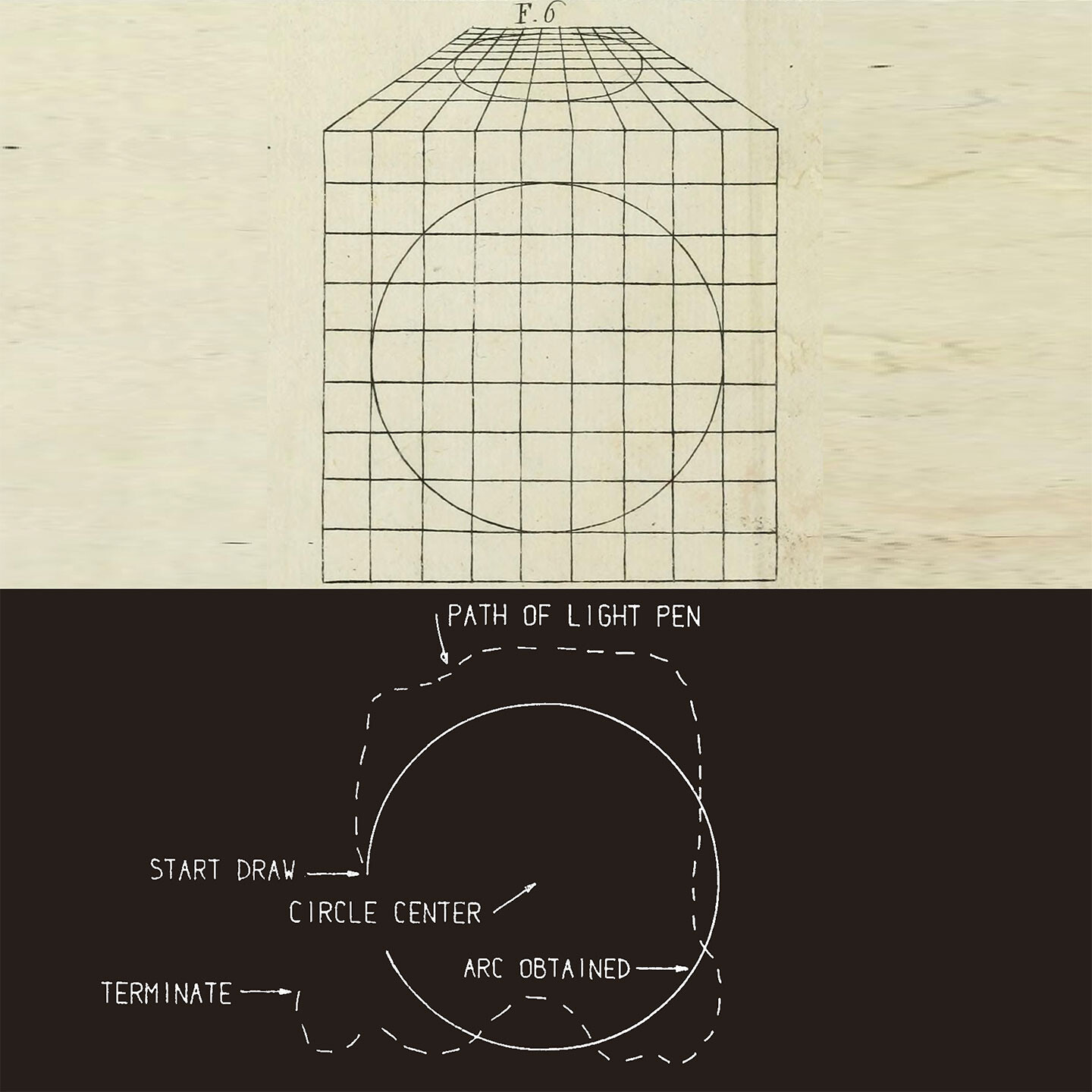

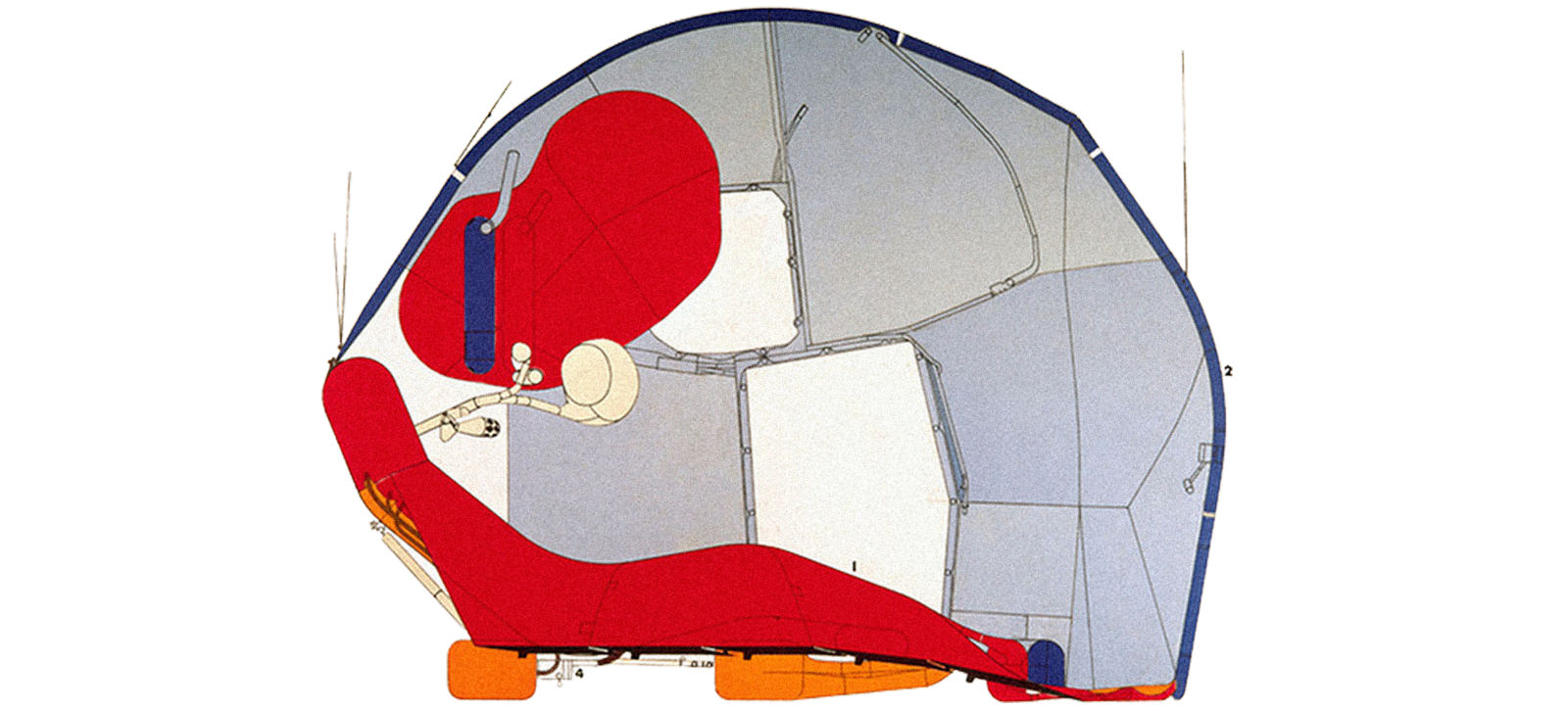

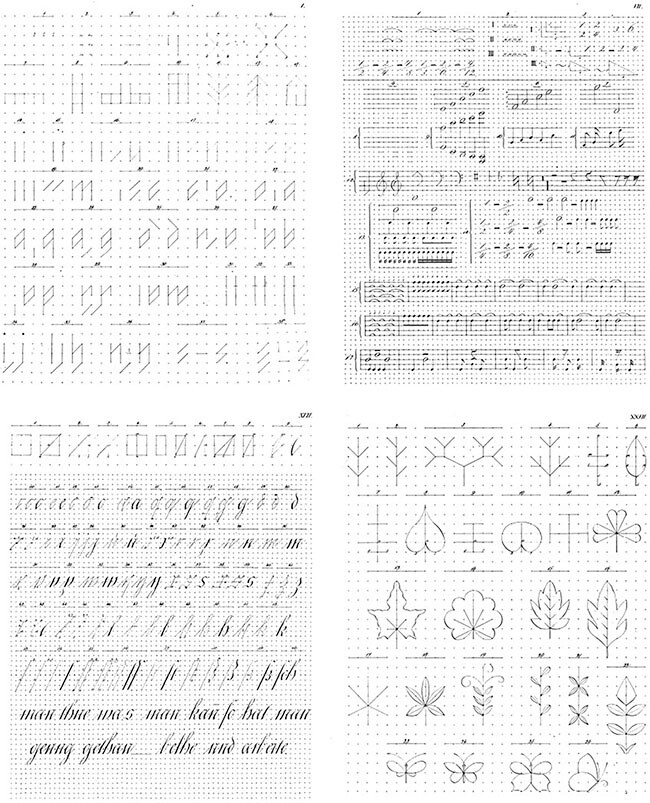

Detail of Hans Hollein, Arrengement of Interrelated Subjects, 1976.

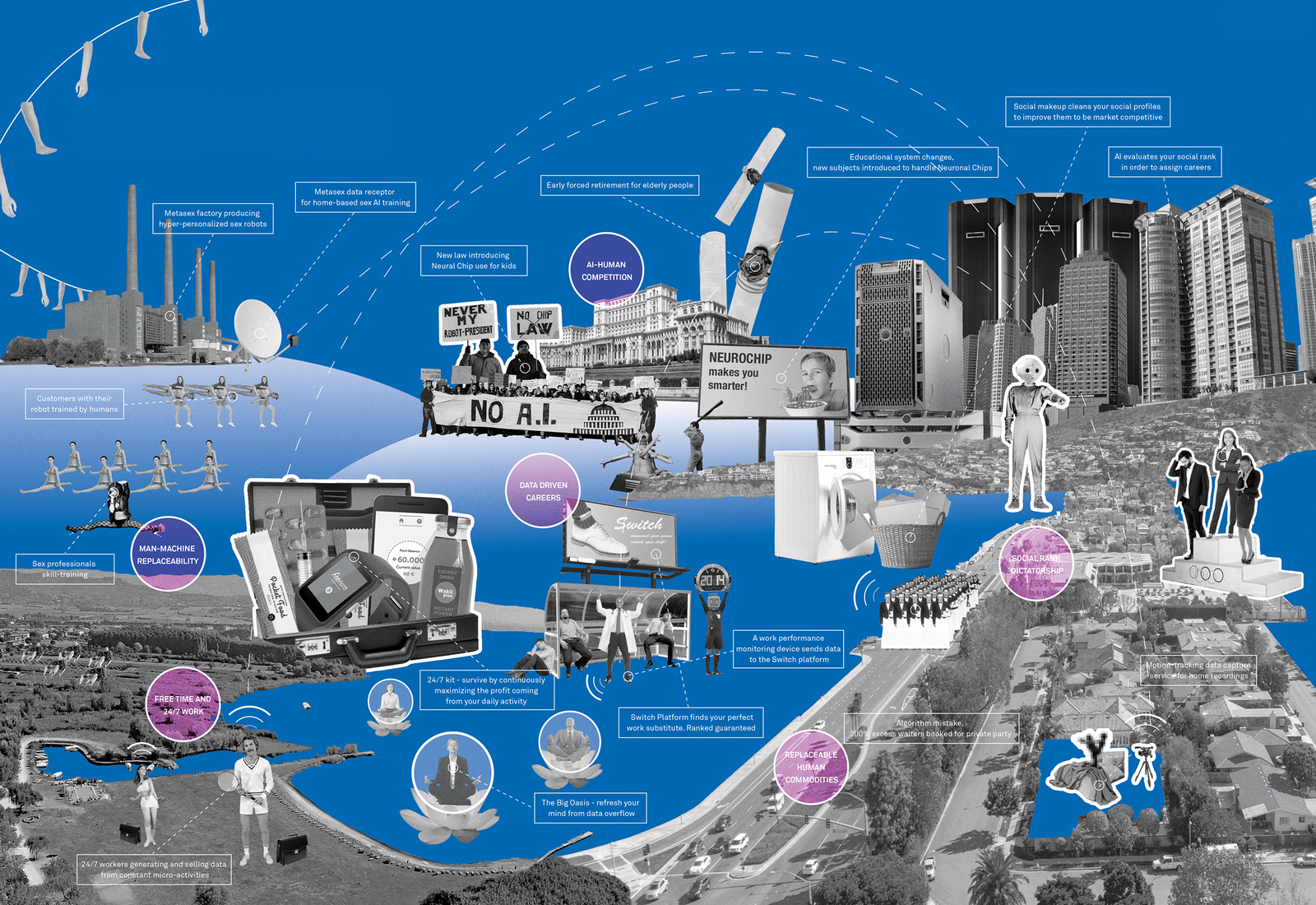

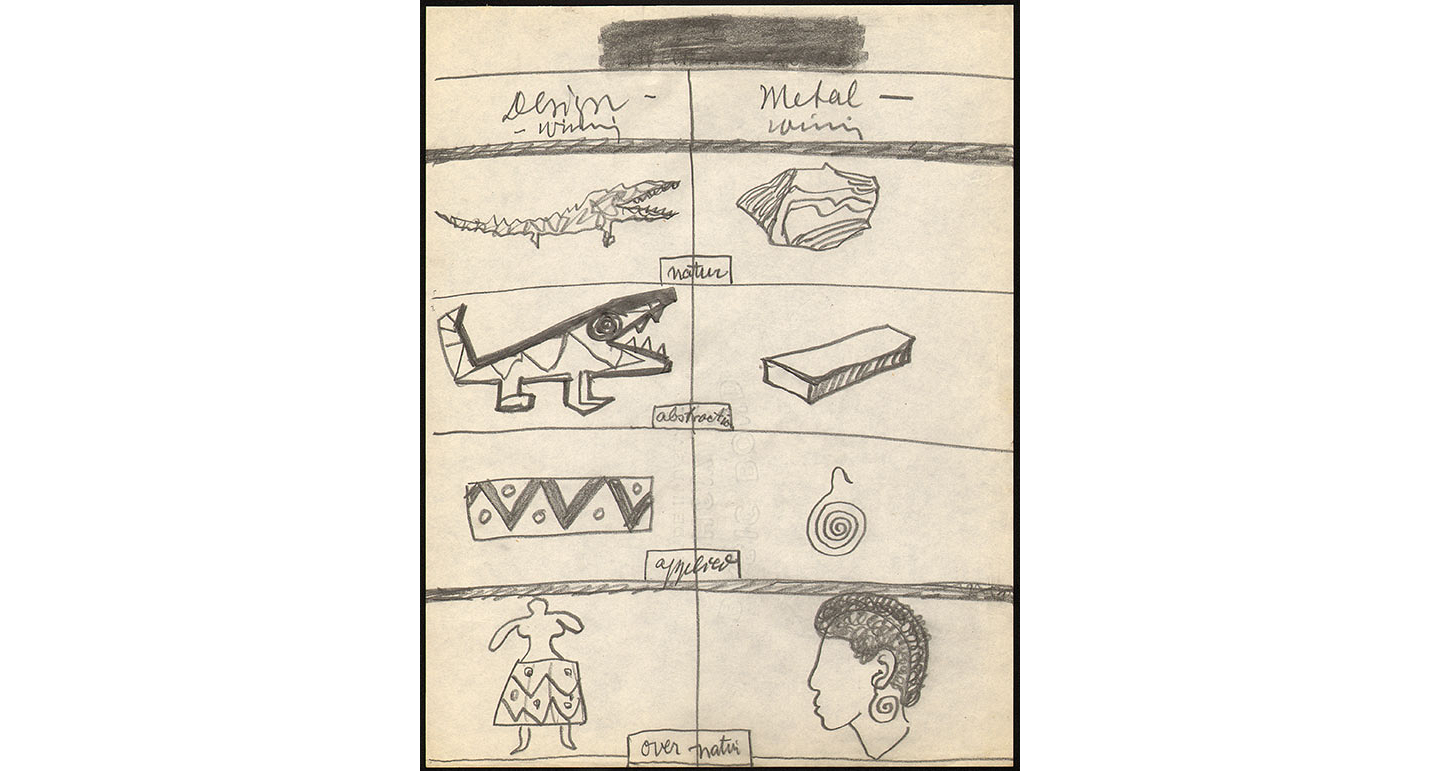

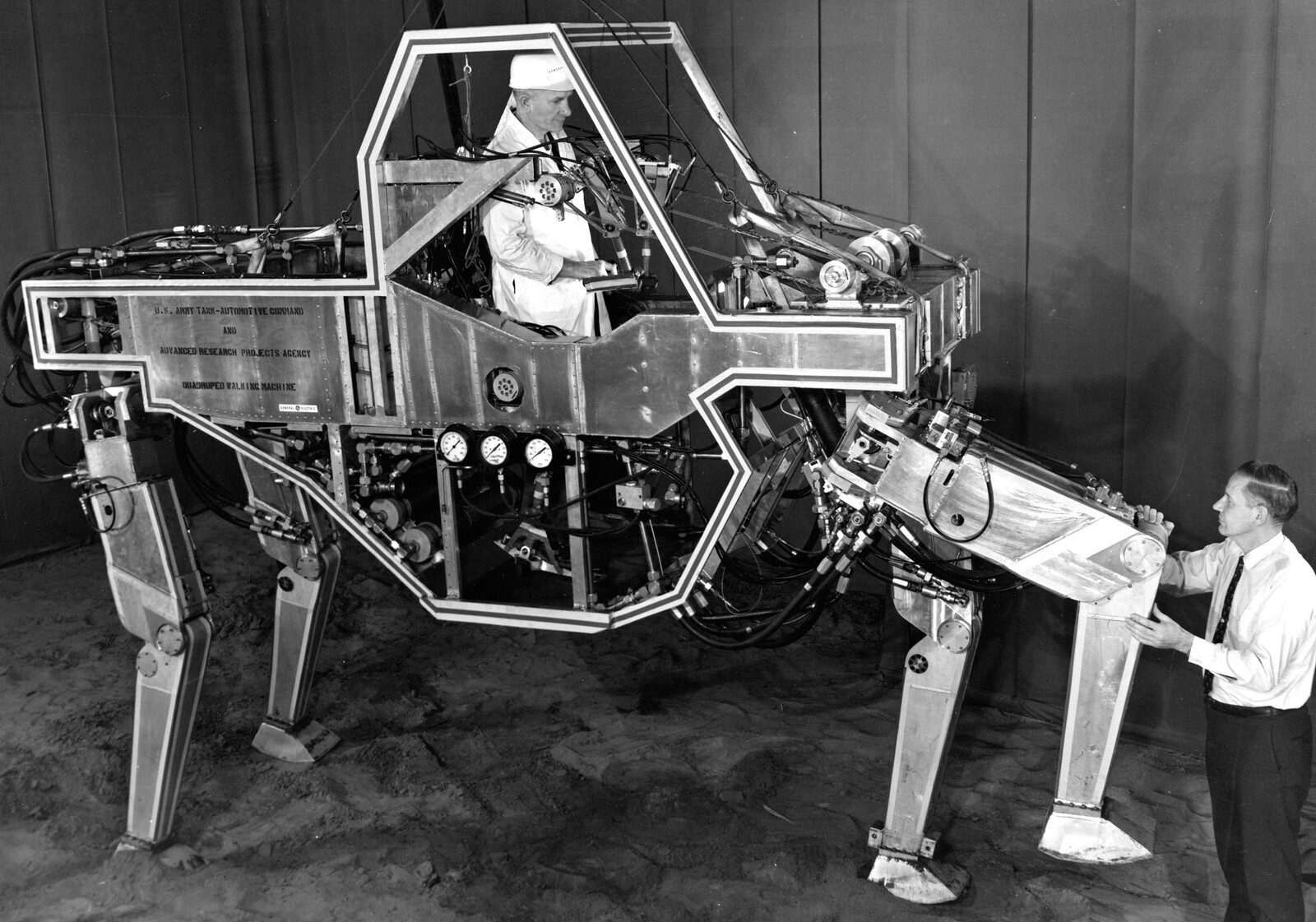

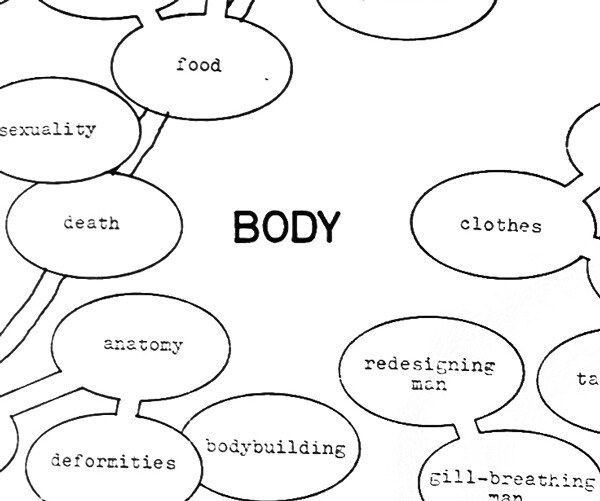

The catalogue of Hans Hollein’s “MAN transFORMS” exhibition of 1976 asserted that “there are mainly two fields of man’s activity: to survive during life and to survive after life.”4 The reason we engage design is, Hollein proposed, “to live and to die and possibly to live beyond death,” which presciently described the condition of the virtual afterlife and the persistence of life’s digital remains after the point of biological expiration. But it also describes the way technologies foster transformations of the body indiscriminately, in both life and death. Perhaps unsurprisingly, a structuring cloud diagram for Hollein’s exhibition featured the central figure of the “BODY.” Among the few “interrelated subjects” that orbited around it were “redesigning the man,” “bodybuilding,” and “death.” Self-design, or rather “self-DESIGN,” according to the frame of the exhibition, is among those transformations which provide the extension of life after death: the survival, twinning, transmutation, or upgrading of the body. While the cases of John Berlin and Bobbi Kristina Brown operate through contemporary mechanisms, Semper provides a corresponding case from the early industrial period.

His and Richard Redgrave’s 1852 design for a hearse for the funeral parade of Field Marshal Arthur Wellesley, the first Duke of Wellington, rematerialized the war hero into a mobile architectural vessel at the heart of one of modern Europe’s largest urban events to date. Their design had the spoils of the Duke’s greatest triumph—“eighteen tons of bronze from cannons captured from his victory at Waterloo”—melted down to form the body of the carriage. The Duke was reinstantiated as a mobile architecture to equip him with a literal visibility to match the celebrity with which he had lived as hero and public figure. The parade drew an audience of three million (on par with John Berlin’s viral viewership) and spawned spin-off celebrations and markets along its course. Hollein’s theory of death-surviving extra-human transformations only holds as long as the living mobilize prosthetic and extra-human upgrades toward the construction and their subsequent participation in economies and societies extended for the afterlife. Once dead, continued participation in society is what ensures survival, fosters ceremony, and proves existence simply by remaining ever-active and ever-transforming.

Not only is one’s own afterlife a design project within the domain of the living, but its very existence is described by the precondition of access and influence between virtual and material channels. John’s memorials to his son—the portraits on the wall, the Look Back video, YouTube uploads, and his own improved body—are only possible because he and his son Jesse participated in social networks online. They agreed to terms of service when first navigating the social media and virtual channels to which they would become lifelong subscribers. They agreed to produce “content” and to commit their casual labor toward the tacit promise of their own eternalization. They are online and proven to have existed. John and his son are now as present in the distributed data banks of the internet as they are in Arnold, Missouri. The Berlin family trailer home exists multiple times over: as an architectural type, as the “real thing,” and as the infinitely reproducible backdrop to home videos. The virtual afterlife of Jesse Berlin has been formed by John’s actions and the series of events following Jesse’s biological death. That is, the level of resolution of its archive, the person it approximates (how they are, how they look, etc.), and how well that accounts for the actual, lived “profile” of Jesse Berlin is a product of several factors, many of which developed after his death.

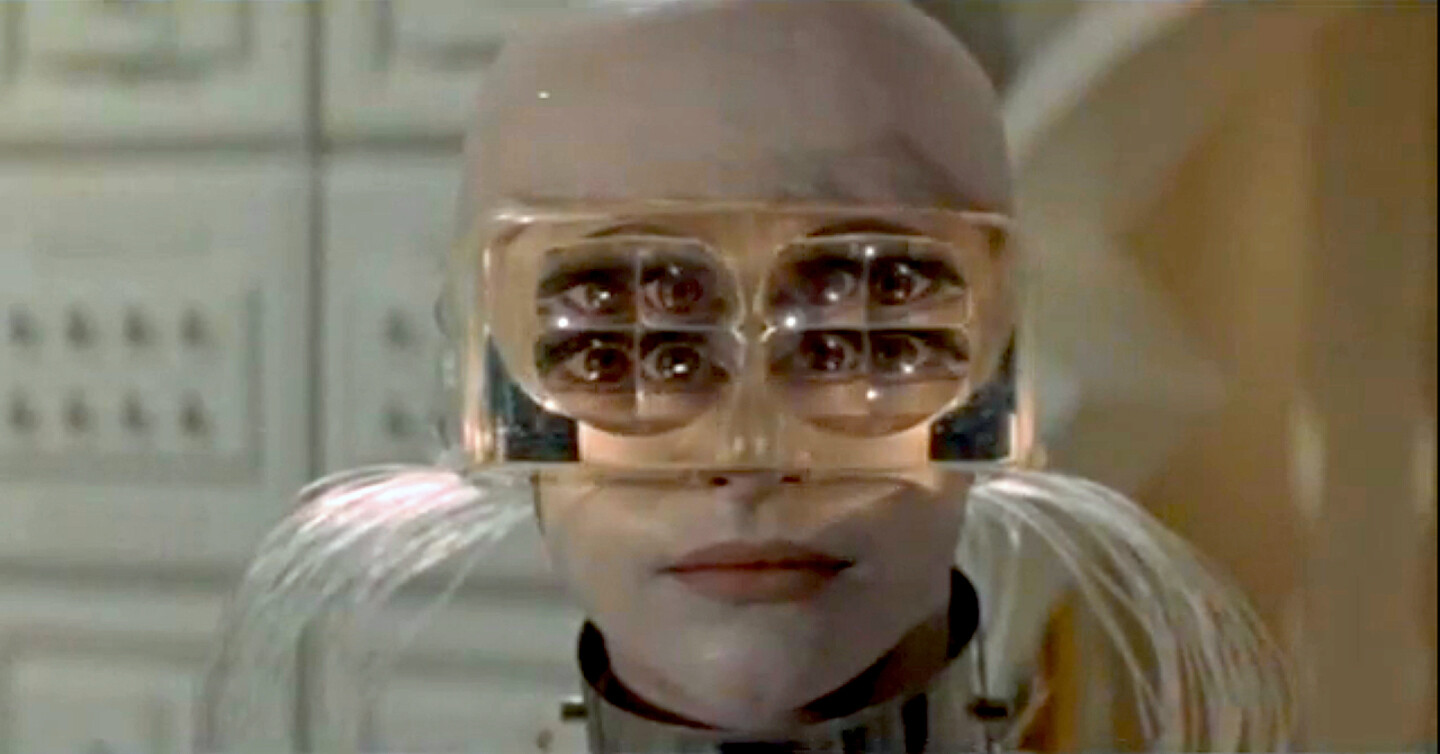

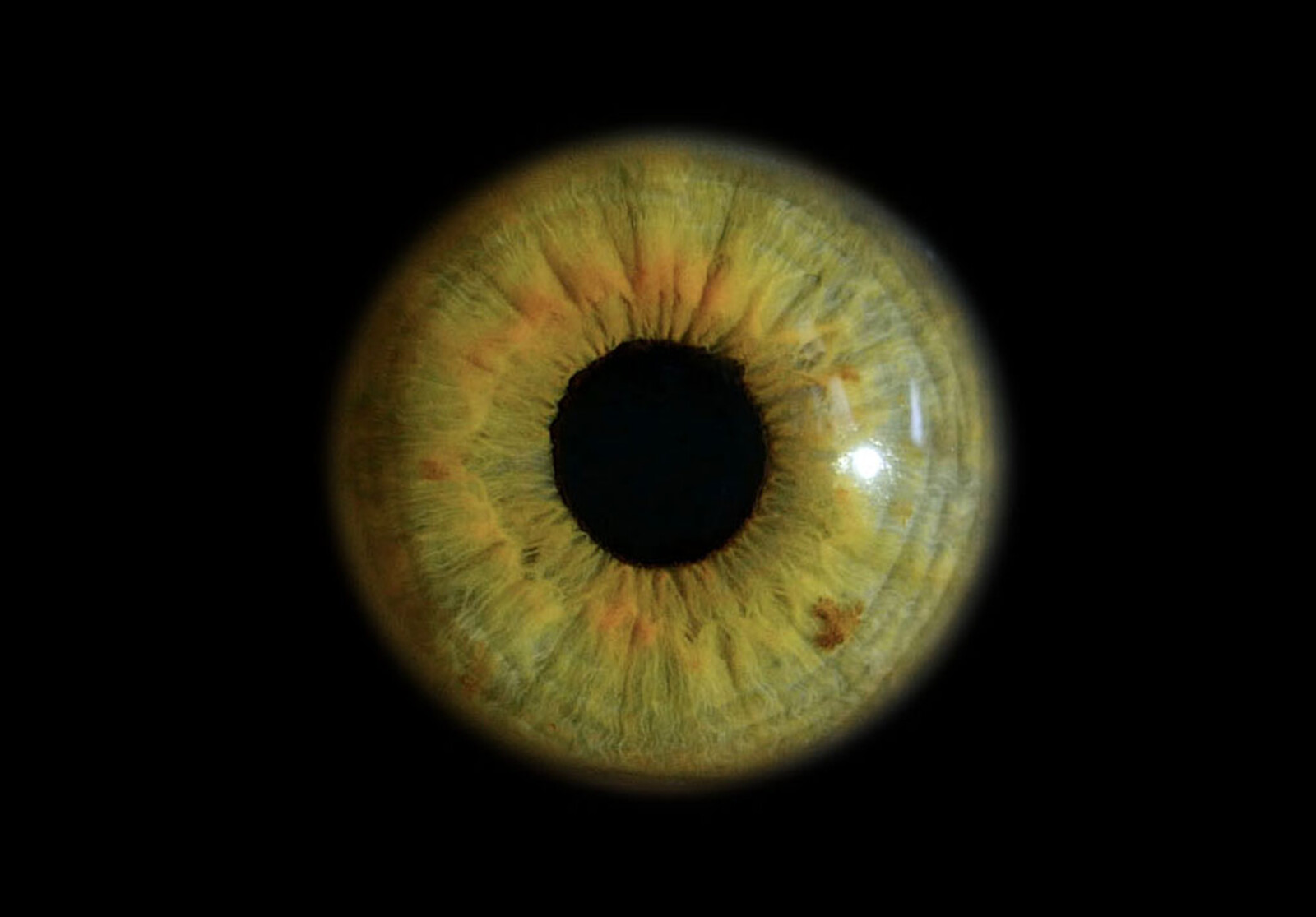

This kind of virtual and material reflexivity via integrated prosthetic enhancement is perhaps nowhere more apparent today than in the world’s most active plastic surgery district, in Gangnam, Seoul. The modern Korean plastic surgery industry originated in the wounded bodies of the Korean War. In the 1950s, American reconstructive surgeon Doctor Ralph Millard began a program of physiognomic reconstructions on survivors of the conflict, which led to the development of new procedures not rooted in an ethos of repair, but of “enhancement.” His invention of blepharoplasty, or double-eyelid surgery, rapidly gained notoriety and is to this day among the most popular surgeries practiced in Gangnam. Gangnam comprises a sophisticated infrastructure—medical, bureaucratic, urban, and digital—that softens its subjects. It promotes a cellular, nutritional, and identity fluidity, both physical and legal. The architectural, infrastructural, and urban technologies of the district—here understood as the attendant technologies that allow participation in and shape the urbanism throughout the process of surgery (before, during, and in post-op recovery)— design the human as a parallel operation to those involving the surgeon’s scalpel. New noses, eyelids, and jawlines demand a protocol across scales; tubing, smoothies, neck pillows, automated beds, cushioned vans, hotel rooms, convenience stores, beauty salons, and shopping centers are the technological and urban counterparts to the bloggers, nurses, beauticians, administrators, and customs agents also required along the way.

The late 1990s and early 2000s marked the period of consolidation of plastic surgery clinics between Gangnam and Sinsa subway stations. At the same time, Cyworld “Virtual Homes” (1999) and Daum Cafe (1999)—the first Korean social media computer programs based on the construction of an avatar or a new self—and Naver Knowledge Search (2002), YouTube (2005), and Facebook (2006) became part of the daily life of millions in South Korea. At the beginning of the new millennium, when clinic towers began to reach a critical mass and participation in virtual worlds multiplied, Koreans could design their avatars with equal fluency in both material and digital worlds. Gangnam is an ecosystem of both radical and mundane logistics for body processing in a context where youth cultures engage in casual worship of the image of the body. It constitutes a cosmetic urbanism where the technologically enhanced face of the patient becomes yet another televisual surface for reprogramming and playback. The transmedia exchange of images—travelling freely between billboards, screens, and faces—demands a sophisticated set of design protocols.

According to the Gangnam local government and South Korea’s National Tax Service, more that five hundred of Korea’s 671 registered plastic surgery clinics were located in Gangnam as of 2015.5 The neighborhood’s doctors attract no less than fifty-five thousand annual foreign patients, and with the amount of collagen imported in a single year, half a million people can be rendered wrinkle-free.6 Seoul’s Banobagi Clinic, for instance, operates on roughly twenty-eight thousand patients annually in a fifteen-story building, while another seventy thousand come through their doors for consultations alone. The fluidity that Gangnam promotes is the result of a deliberate techno-urbanism instrumentalized toward the redesign of the human body. The public video diaries of East Asian beauty bloggers hired to advertise clinics through their own surgeries reveal the overabundance of cellular fluidity that the micro-violence of the surgical procedures instigate. They reveal the swelling and bruising that obscure the body in the two weeks of recovery following surgery and the healing that follows through its auto-metabolization. During this time many patients, including medical tourists who have travelled to Seoul from afar, take up residency in the neighborhood.

The district’s cosmetic skyscrapers are unique socio-technological ensembles that simultaneously engage extreme conditions of radical isolation and hyper-connectivity. The towers isolate themselves with ornamented and screened façades, masking any external reading of the clinic interiors, and by consolidating retail and pharmaceutical programs within, reducing the need for clients to leave and engage the neighborhood. In contrast, the fluidity and connectivity that the plastic surgery towers demand in the city’s public realm are critical to their survival. In Korea—the fastest and most web-connected country in the world—an extreme body-consciousness and the rate at which body images circulate in social media have pushed clinics like Regen Plastic Surgery to redirect advertising from subways, streets, and buses to KakaoTalk groups, YouTube vlogs, Daum forums, BabiTalk posts, and Instagram micro-celebrities. The urban space for casual encounter, discussion, and participation in an outward display of a consciously photogenic lifestyle—the material and social aestheticization of one’s daily life—might as well be located thousands of kilometers away from Gangnam. The bedroom of an Indonesian, Singaporean, or Chinese lifestyle blogger is one of the backdrops where the cosmetic agora opens up, where people meet, negotiate, and argue about past, future, and hypothetical body updates.

The paradoxical condition of simultaneous social hyper-connection and physical isolation collapses in a single architectural space: the lobby. This is the site where aspirations for enhancement, both individual and collective, virtual and physical, collide. Traditionally understood as the space for sociality as well as the portal that welcomes the urban realm into the building, the ground-floor lobby of the plastic surgery tower is now a residual space entertaining a minimum amount of public interface. At street level, the sixteen-story BK Plastic Surgery tower has a single 4.5-square-meter lobby. The fifteen-floor Regen Clinic is accessed by a 1.4-meter-wide, 12-meter-long corridor. Both of these towers, as well as many others, provide reception spaces—with some other functions associated with lobbies—on higher floors, where check-in desks greet patients right out of the elevator. But reception isn’t kept at such heights just for the spectacular view. The lobby no longer has to occupy storefront space since most patients already know exactly where they’re headed after having made their appointment online. Many of the clinic’s website menus even match those of their elevators, adopting the building section as navigational framework. The virtual realm has obviated the need to materially appeal to the passerby. Although plastic surgery is a somewhat public affair in Seoul, hidden lobbies keep the fluid patients well within the procedural confines of the tower, and out of reach of the plastic forces of the neighborhood, effectively reproducing the virtual communities that clinics seek to foster with vlog-based endorsements and day-by-day patient diaries. Gangnam’s online participation amounts to a form of reality television: a web series, with the consultation, surgery, and recovery rooms as the set for a patient’s solo performance.

How can the ritualistic condition of the prosthetic body be mined for new urban protocols of the everyday? How might ceremonialized transformations of the body produce new opportunities for the production of value? And what is architecture’s role in the redesign of the body—living and dead—in an age of constant self-fashioning? The human body is not only a site of design, but a simultaneous instrument for the instant and reflexive design of its own prostheticized environment and image. That is the nature of Semper’s vessel: whether as an avatar, bathtub, trailer home, carriage, clinic, or web server. In this mode of plastic reflexivity, the human is enlisted as the design agent that initiates a productive reciprocity between the body, other bodies, and the techno-urban ecology. This is the spirit of self-design: precarious operativity on a fluid spectrum between death and healing: “a condition in between destruction and regeneration.”7

Mike Fleeman, “Bobbi Kristina: Mom Whitney Houston Talks to Me in Spirit,” People Magazine, March 12, 2012.

Gottfried Semper, Style in the Technical and Tectonic Arts; or, Practical Aesthetics, trans. Harry Francis Mallgrave and Michael Robinson (Los Angeles: Getty Publications, 2004), 467.

Ibid.

Hans Hollein, MAN transFORMS (New York: Cooper-Hewitt Museum, 1976).

Gangnam Community Health Center, “Clinic Index,” 2015, ➝.

“Plastic Surgery Boom Reaches Alarming Proportions,” The Chosunilbo, November 21 2009.

Semper, Style in the Technical and Tectonic Arts, 71.

Superhumanity is a project by e-flux Architecture at the 3rd Istanbul Design Biennial, produced in cooperation with the Istanbul Design Biennial, the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea, the Govett-Brewster Art Gallery, New Zealand, and the Ernst Schering Foundation.

Category

Superhumanity: Post-Labor, Psychopathology, Plasticity is a collaboration between the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea and e-flux Architecture.