The question of “superhumanity” presupposes that there might exist something other than the human in the human, a presupposition that might be as old as humanity itself. Such an idea has known many returns. It has continuously been addressed within the philosophical tradition, and indeed, it is returning again today.

In October of 1968, at a conference in New York called “Philosophy and Anthropology,” Jacques Derrida gave a keynote address entitled “The Ends of Man.” In it, he insisted on how difficult it is to open a space between, on the one hand, the innumerable differences that hide behind the word “human”—national, ethnic, cultural, gender—and on the other, the universality of the term’s overt signification. Addressing the organizers of the conference, Derrida wrote,

At a given moment, in a given, political, and economic context, some national groups have judged it possible and necessary to organize an international encounter, to present themselves, or to be represented in such [an] encounter by their national identity (such, at least, as it is assumed by the organizers of the colloquium), and to determine in such encounters their proper difference, or to establish relations between their respective differences.1

Fifty years later, we are confronted with the same issue. I am necessarily trapped within the paradoxical injunction of articulating my position from a particular place, the perspective of my own culture and identity—that is as a French, or at least European, philosopher—which prevents me from universalizing my discourse, and yet nonetheless hope I to develop something that can be understood by an unknown audience.

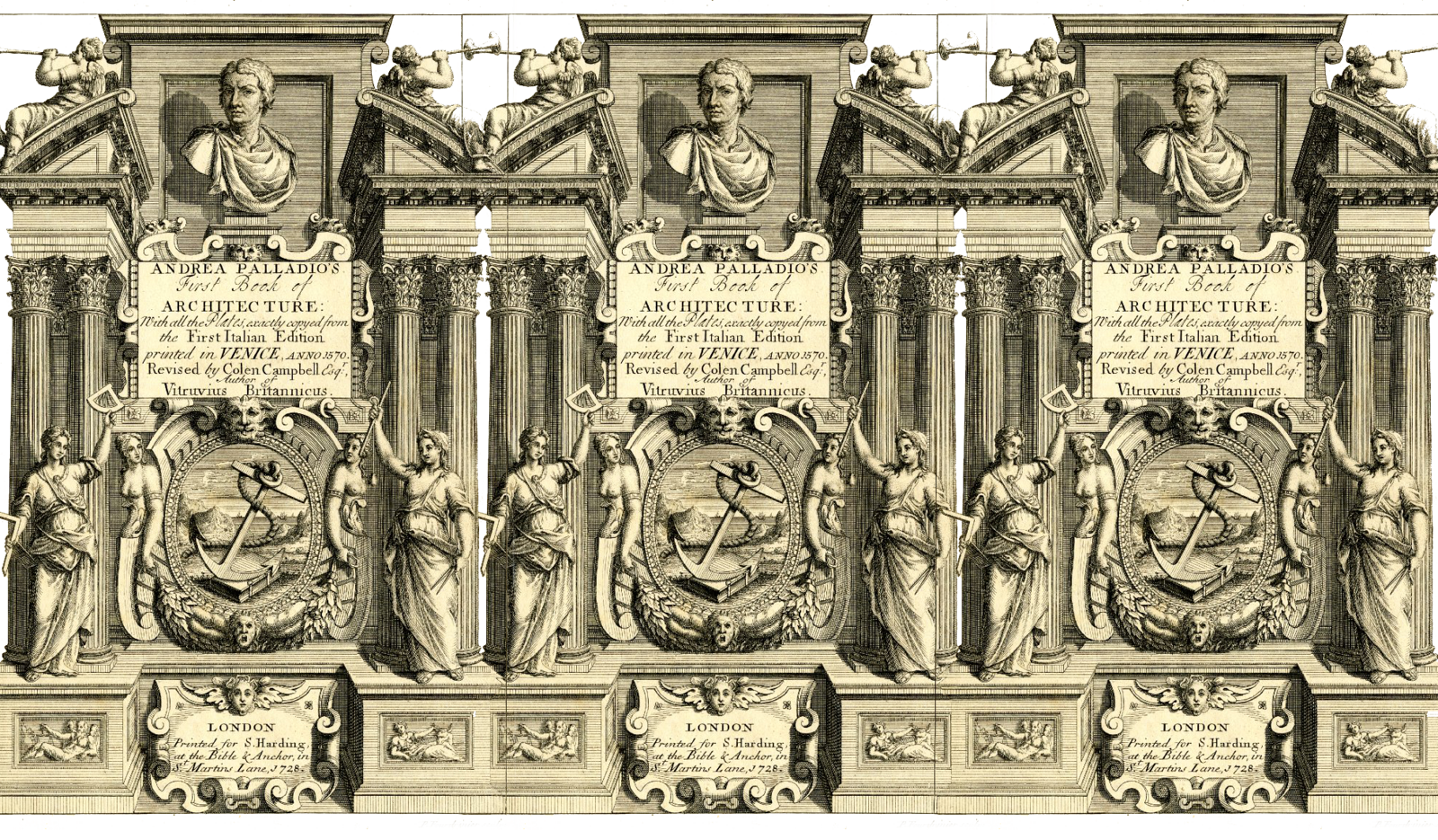

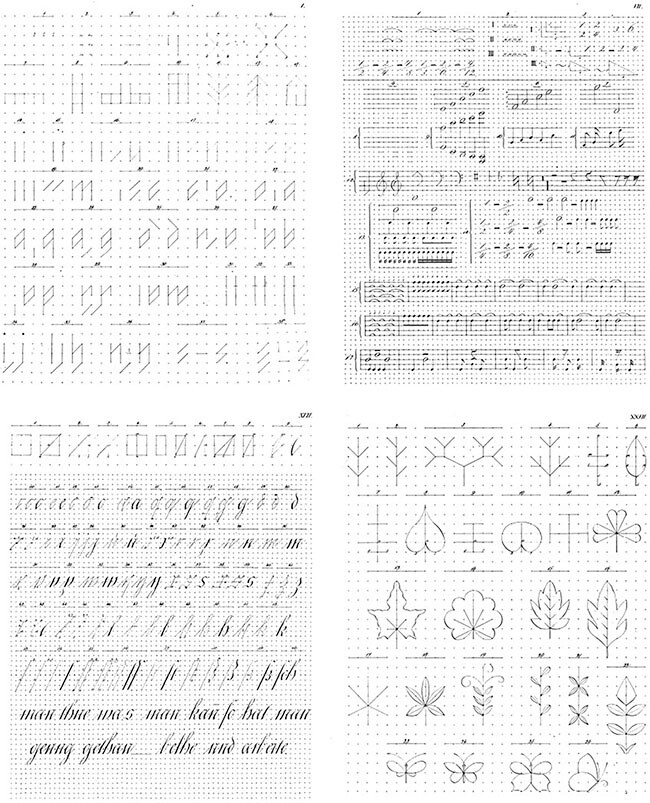

If I explicitly present my discourse as a repetition, a reiteration of Derrida’s, it is because I intend to demonstrate that the question of the human is linked with repetition in a very specific way. This is not to say that repetition is specifically human. There are of course innumerable occurrences of animal repetition, as well as many cases of nonliving repetition: automatisms, mechanisms, etc. So the human is not the repetitive or repeating character per se, but its relationship to recurrence is perhaps unique, and can be formulated as follows: the human does not exist prior to repetition, but is designed by it. The human is the product, not the origin, of repetition. What, then, is this plastic operation, according to which fashioning has priority over being? Can it be understood as a mold for the superhuman?

The inhuman (the historical problem of evil), the nonhuman (animal or machine), or more recently, the transhuman and the post-human are all different versions of the same idea, that the human might contain its own alterity. We can therefore say that the human is that which repeats itself beyond, and perhaps even in spite of, all attempts to challenge or deconstruct its essence. The “properly” human relationship to repetition is thus always at the same time a debasement of any “proper” essence of the human.

To return briefly to the title of Derrida’s lecture, we should read the meaning of “end” to be double, both as disappearance and accomplishment. The human is achieved in its disappearance, in becoming inhuman, nonhuman, post-human… Such is the apocalyptic nature of the human: its destruction is its truth, whereupon the unity of death and completion, dissolution and achievement, are to be revealed.

Even Derrida himself presented his own talk as a repetition, which follows in the wake of Nietzsche and his proclamation that a new human was coming. This nonhuman human, the “Overman,” was above all else characterized by its plastic quality; it was the incarnation, the very body of plasticity. Yet if there is something specific to the human for Nietzsche, it is precisely what he calls the spirit of revenge. For Nietzsche, revenge is essentially another name for repetition. Revenge, taking revenge, wreaking, meaning to push, drive, herd, pursue, persecute … The human is the only being that seeks revenge after an offense. This should not be confused with, for example, divine punishment, for gods can punish men, but they don’t seek revenge proper. It has nothing to do with struggle or conflict either: animals can fight and kill each other, but it does not occur out of vengeful instinct. Revenge is human, all too human.

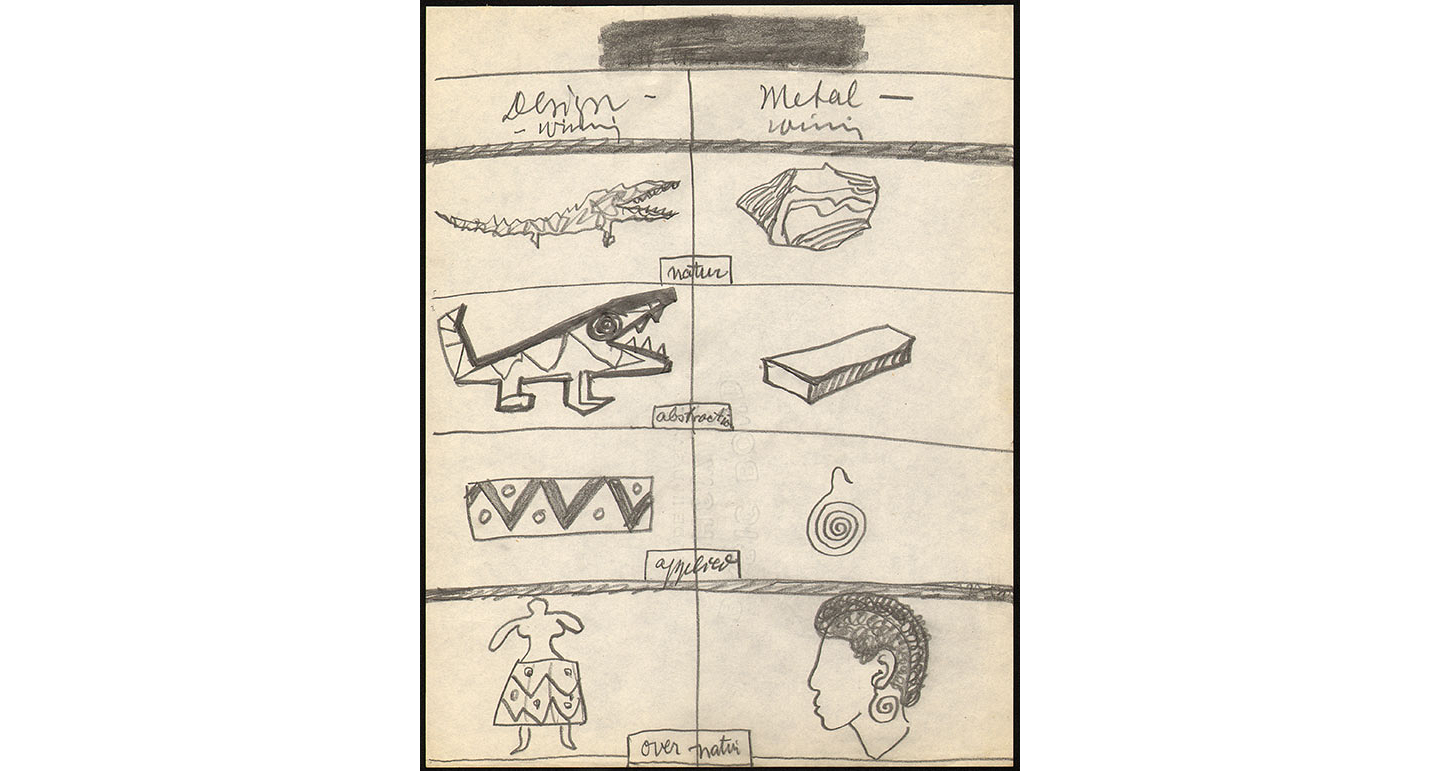

The human is a being who cannot forget offense, who cannot erase the past, and constantly ruminates over it. Plasticity, as we know, designates the capacity to concurrently receive and bestow form. Thus one who creates—the artist, for instance—is simultaneously created anew by their work. Yet as we can hear in the words “plasticage” or “plastic,” the putty-like explosive, plasticity also implies the ability to destroy oneself. We can therefore affirm that each creation is at the same time an explosion of a previous form. While an imprint is kept, it becomes difficult to recognize the past in its new identity. Revenge, on the contrary, implies rigidity, incapacity to change, and attachment to sameness. How, then, can repetition be assimilated with plasticity, if it is in essence nonplastic, mechanical, and iterative? If plasticity implies explosion and forgetfulness, can it be linked with repetition?

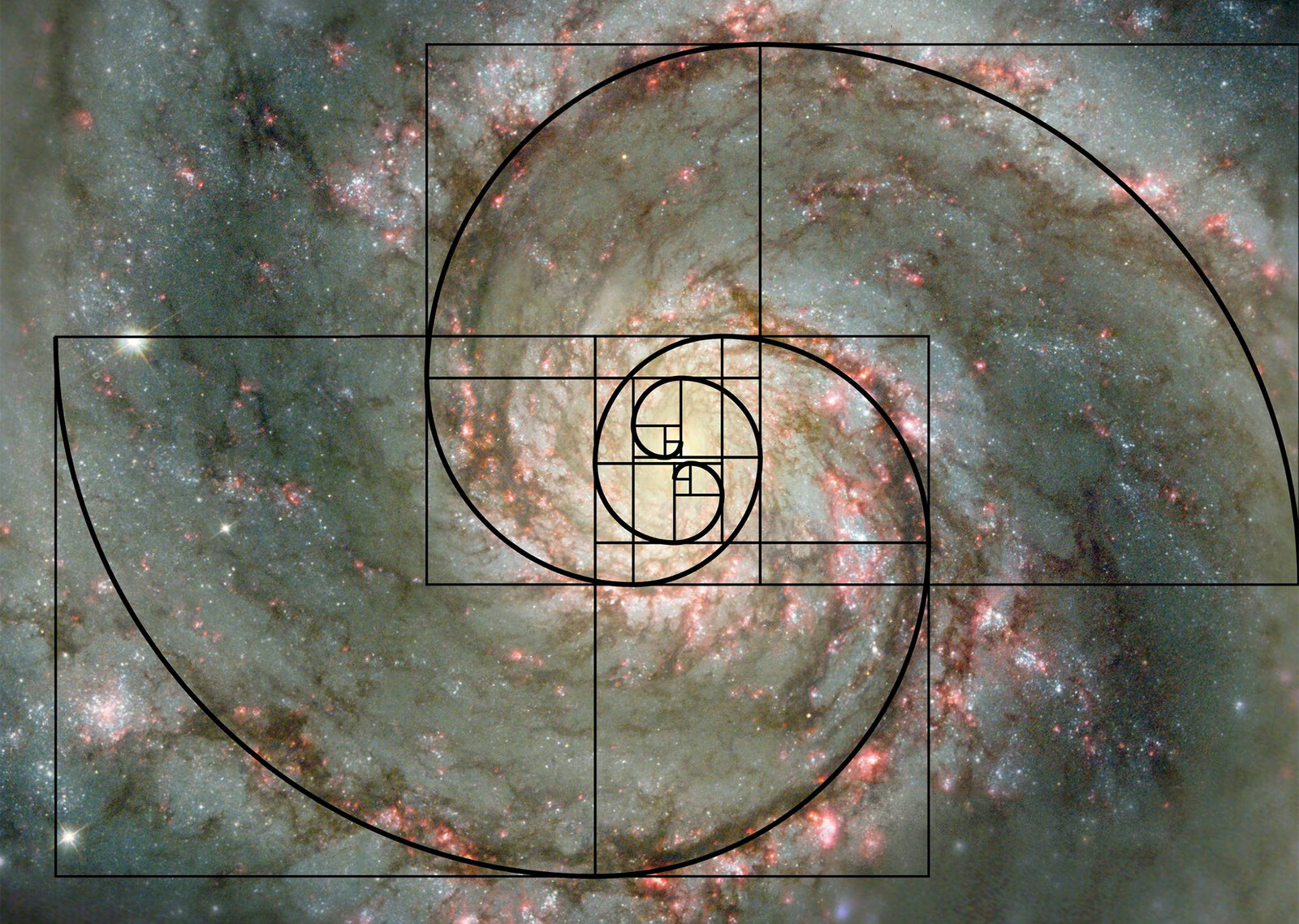

In order to answer these paradoxes, we first have to inquire where, for Nietzsche, the spirit of revenge and repetition comes from, about which he is adamant: it originates in a relationship to time. The human is the only being for whom time is a spiritual injury. If there is only one thing the human seeks revenge for, it is the passage of time, and thus, of course, finitude. Having to die is the utmost injury. Time is the utmost offense. In this regard, Nietzsche, through Zarathustra, says: “This, yes, this alone is revenge itself: the will’s ill will toward time and its ‘It was.’”

Revenge is not only revenge towards the past, but resentment toward temporality in general. Here, “past” means “passing away.” Revenge is the will’s ill will toward time, toward passing away, toward transiency. Transiency is that against which the will can take no further steps, that against which it constantly collides. There is nothing we can do against time. Finitude is the unpassable obstacle. Life is short, what is done is done. This engenders resentment. We repeat what we cannot change. We repeat because we cannot change. The essence of humanity is to repeat its anger and dispossession; it is always too late. For a god, it is always early. For an animal, time is always now. But for the human, time is a repetition of instants that each say “nevermore.”

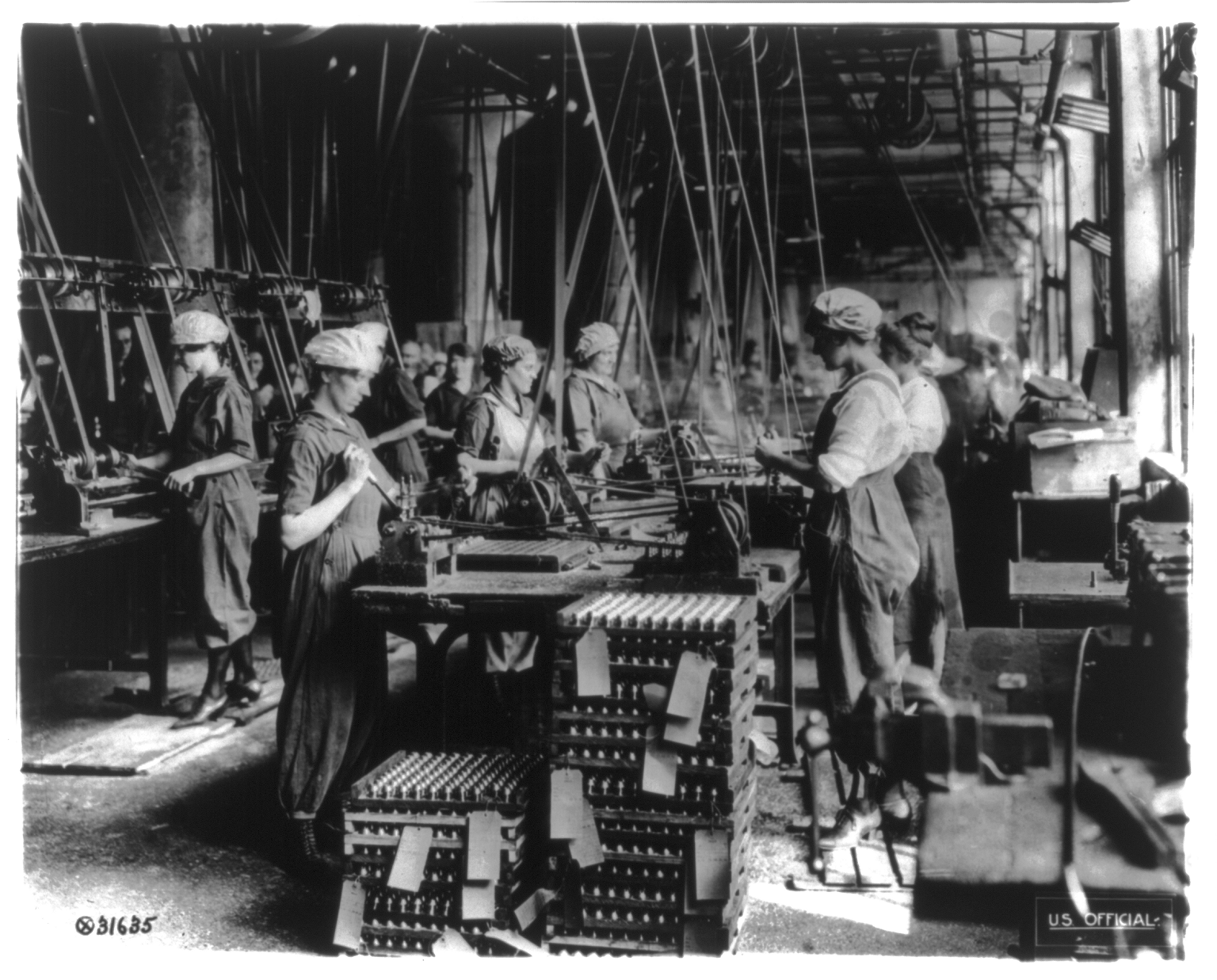

Competition, wars, profit, and labor exploitation are all too human, rooted as they are in the vengeful instinct, the rage against transiency and the impossibility to start again, anew. Yet at the same time, humans are constantly trying to escape the spirit of revenge, to emancipate themselves. In democratic states, for example, law is supposed to guarantee the functioning of justice against any private acts of revenge. The birth of written laws and codes in ancient Greece appeared as the triumph of logos and reason over revenge and subterranean authority. Democratic law is still currently perceived as a rational system that opposes personal, unruly ways of settling conflicts. From the perspective of democratic institutions, for instance, vendetta and other modes of revenge are considered uncivilized. We think that law has won, or at the very least should win, over revenge. But in fact, as Nietzsche claims in the second treatise of the Genealogy of Morals, law is not the end of the spirit of revenge, but rather its very accomplishment. Law, Nietzsche writes, is the institution which tries “to sanctify revenge under the name of justice, as if justice were basically simply a further development of a feeling of being injured, and to bring belated respect to emotional reactions generally, all of them, using the idea of revenge.”2

Justice is simply a new, more subtle, refined version of revenge. Reason, law, and morals disguise resentment as ideals. Discourse and code serve to conceal haunting bitterness. Yet in spite of being hidden, repetition repeats in the form of retribution, retaliation, punishment, and the like. The ghost of time comes back again. The human is still there. We are humans, seeking revenge for being human.

While condemning humanity to the repetitive spirit of revenge, Nietzsche also points towards a potential for liberation, and the Overman, or Superman, is its name. “For that man be redeemed from revenge—that is for me the bridge to the highest hope and a rainbow after long storms.”3 Emancipation from revenge is exposed in the extraordinary chapters of Thus Spoke Zarathustra “On the Vision and the Riddle,” “The Tarantulas,” and “The Great Longing.” Zarathustra begins the last with the words: “O my soul, I taught you to say ‘Today,’ ‘One Day’ and ‘Formerly.’”4 Zarathustra teaches his soul to treat time in a non-vengeful way by reforming its relationship with repetition itself: instead of thinking of repetition as the return of the same—that “most abysmal thought”—he learns to recognize that the space for difference it opens. That is, he learns to affirm what is repeated, thus transforming repetition itself. Instead of passively bearing what happens, one can desire it, plastically.

“Redemption,” Heidegger writes, “releases the ill will from its ‘no’ and frees it for a ‘yes.’” To renounce revenge, that which leads to the Overman, implies what Nietzsche calls “active forgetting” (“aktive Vergessenheit”). Yet is it possible for the human to actively forget what it is? Will we ever be liberated, freed from revenge, and thus from our humanity? Will we ever be able to invent a new relationship to time, to law, to justice? If I raise the question of repetition today, it is not only because the human is what repeats itself, but also because repetition has become paradigmatic of contemporary theoretical and institutional practices. Repetition has, in other words, become culturally dominant. More than ever, repetition has become the raw material of our lives. Is this phenomenon conferring more plasticity onto our humanity? Can it achieve our superhumanity?

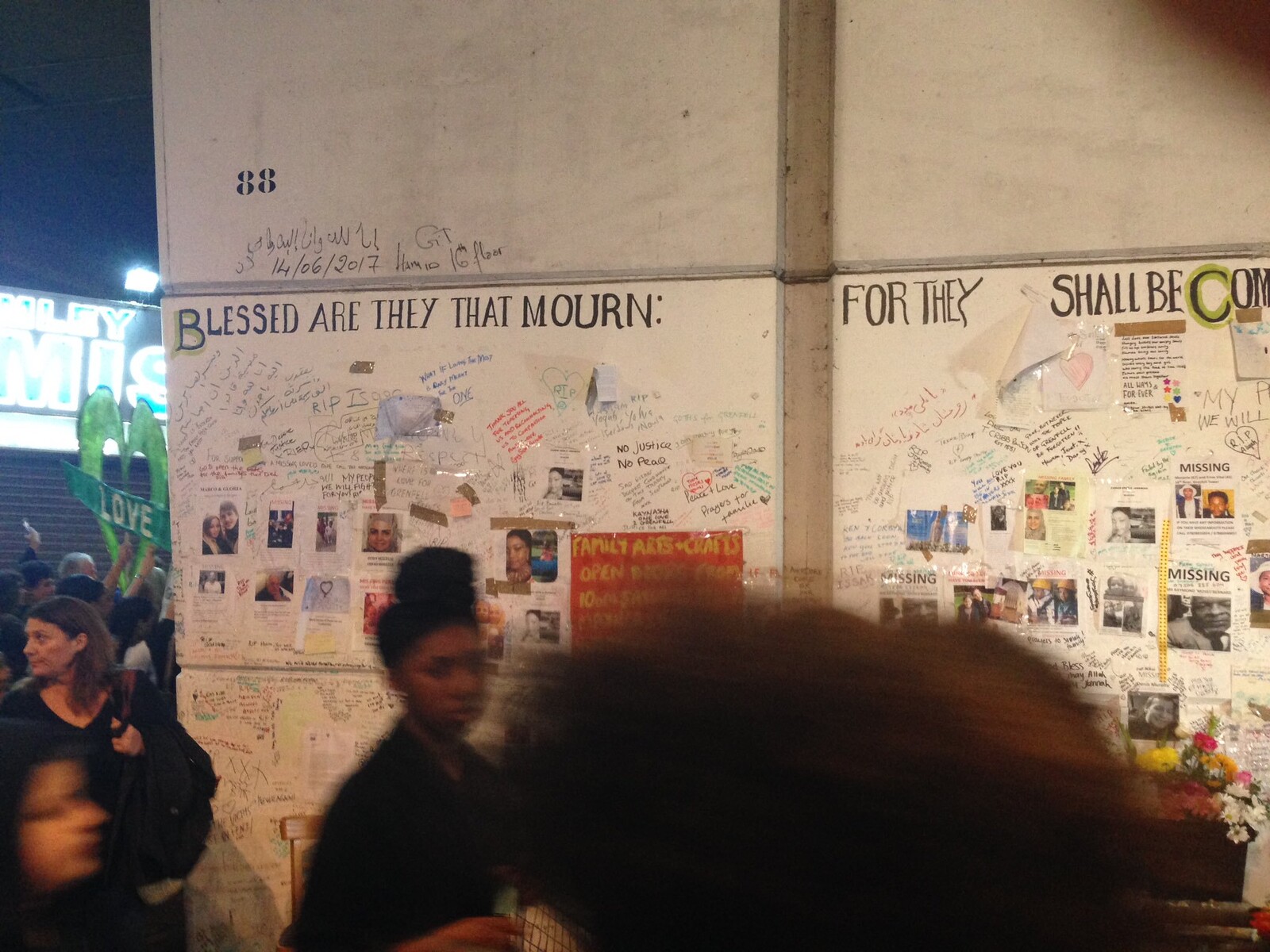

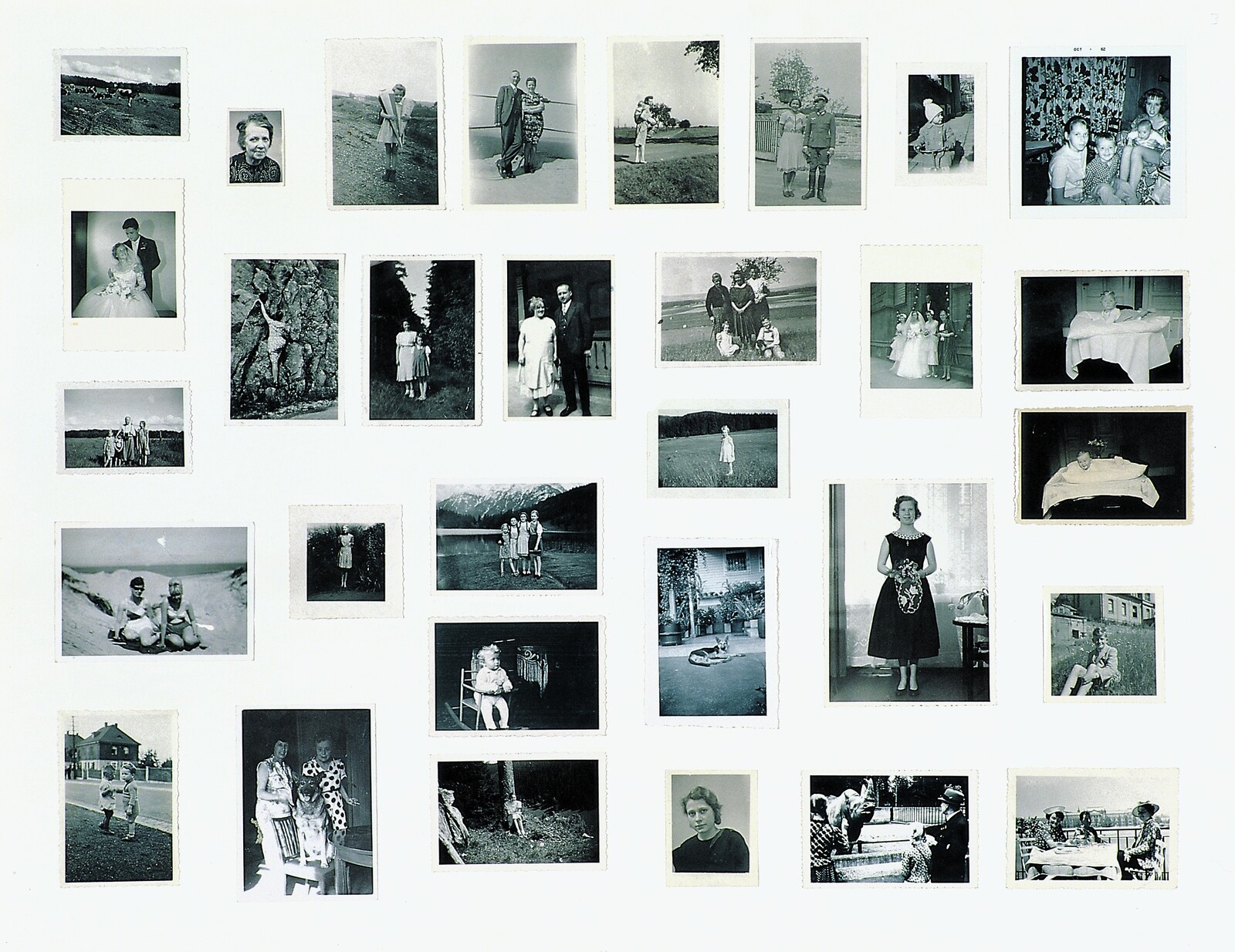

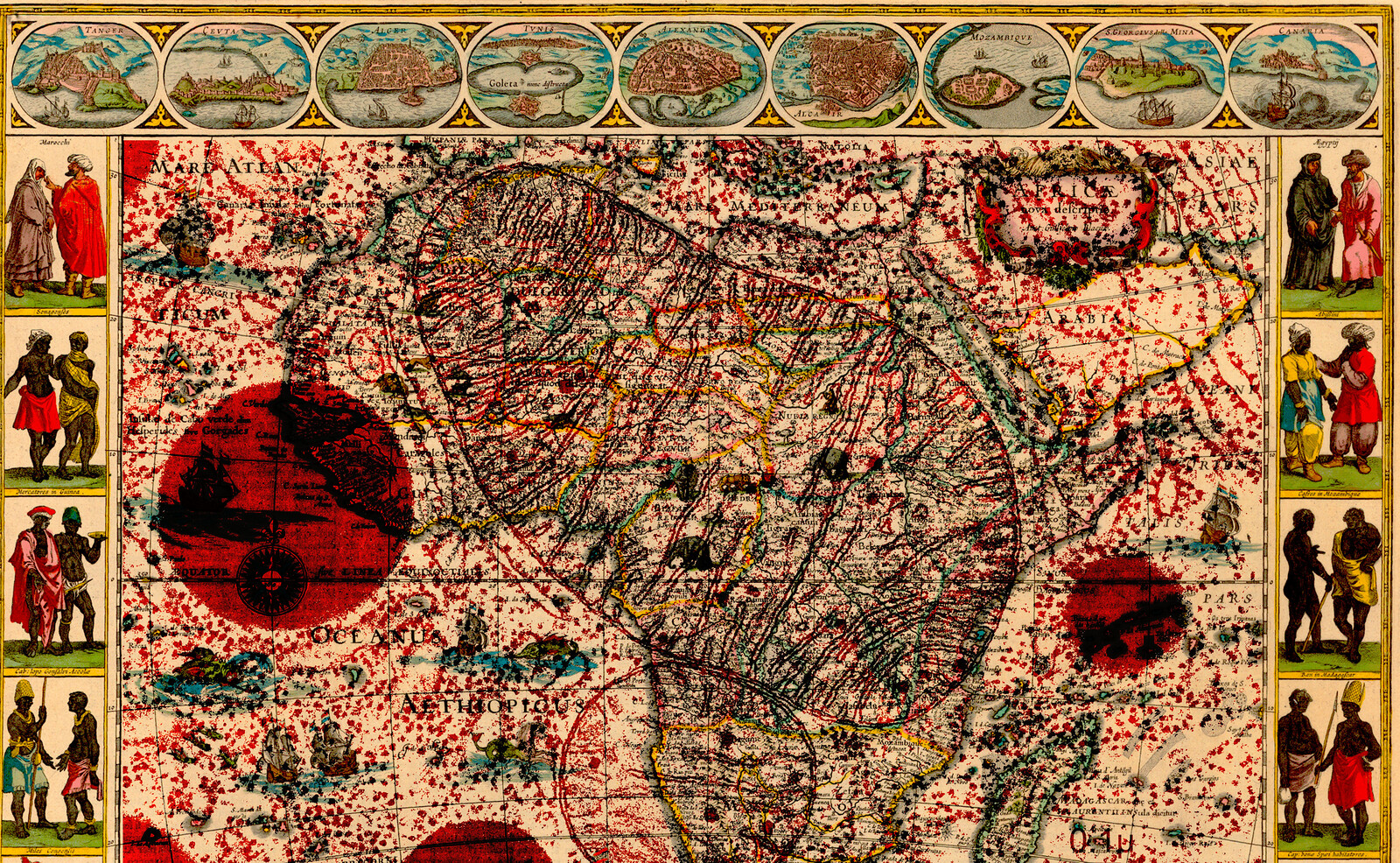

In the juridical domain, the issue of return has become crucial: as the return of indigenous lands, as reparations and recognition in postcolonial law, as forgiveness for apartheid, as acknowledgment of war crimes, etc. Questions of memory, ancestrality, and genealogy are acute today, as if what comes back, what returns, what needs to be repaired and restituted, were the most urgent of all problems. As Derrida notes, the urge for repetition, for forgiveness and repair, for repentance and redemption, for remembrance in order to forget, to repeat in order not to repeat, has become so strong that it has become transgressive:

The [current] proliferation of [the] scenes of repentance and asking for forgiveness no doubt signifies, among other things, an “il faut” [moral necessity], of amnesis, an “il faut” without limit toward the past. Without limit, because the act of memory, which is also the subject of the auto-accusation, of the “repentance,” of the [court] appearance [comparution], must be carried beyond both legal and national state authority.5

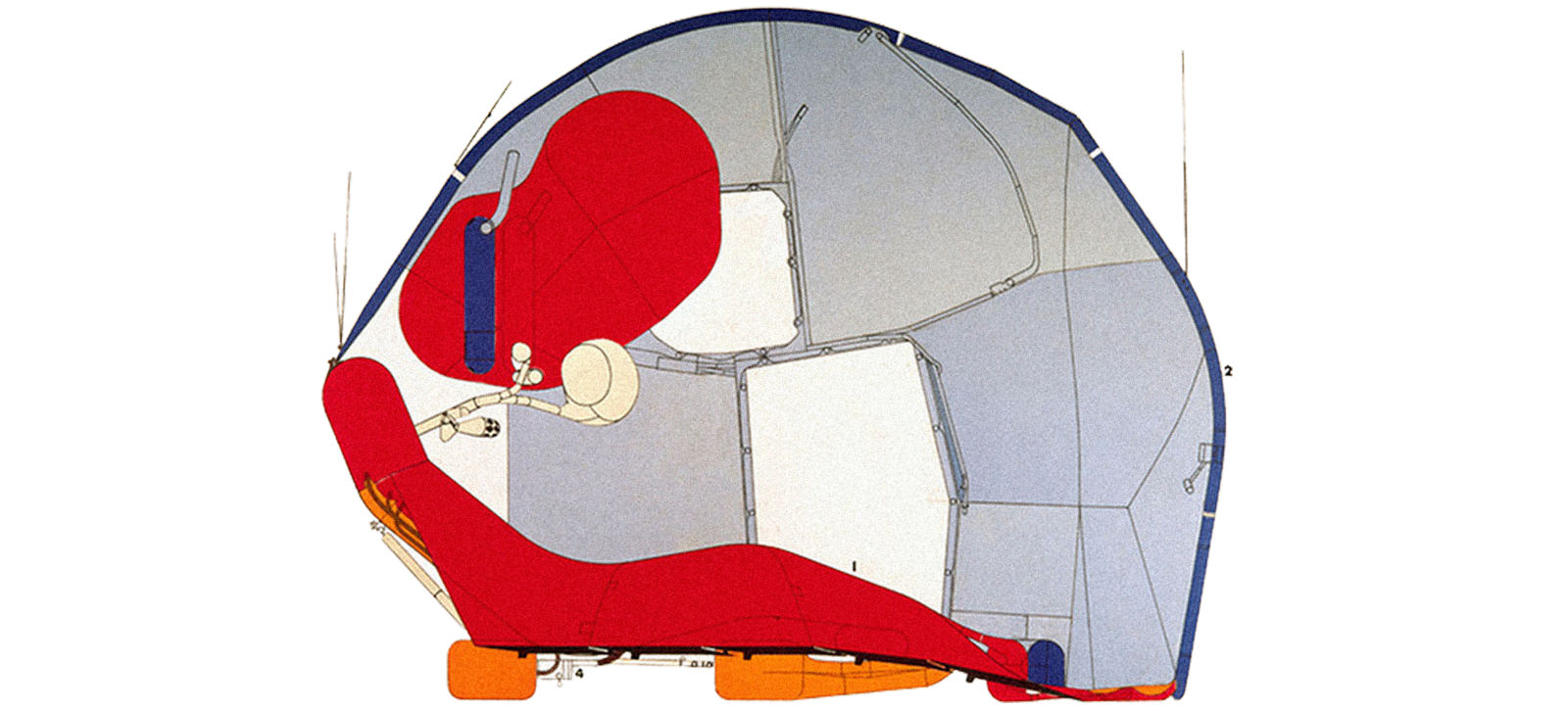

Another striking example of the current thematic insistence on repetition is biology. Repetition plays a major role at all levels of contemporary molecular biology, particularly in genetics and epigenetics. Think of stem cells: these nonspecialized cells, present in every important organ of mammalian bodies, have the capacity to transform themselves into any kind of cells. They also can “self-renew” to produce more stem cells. There are two types of stem cells: embryonic and adult. In a developing embryo, stem cells, called “pluripotent” cells, can differentiate into any type of specialized cells. Adult cells are conversely said to be “multipotent,” meaning that they can transform themselves into a limited gamut of specialized cells.6

In 2006, Japanese Nobel Prize winner Shinya Yamanaka created pluripotent stem cells (iPS) from multipotent ones, transforming them back into an undifferentiated state and effectively erasing the difference between adult and embryonic stem cells. This example, among others, characterizes the phenomena of what is today known as “stem-cell plasticity.” The entire field of regenerative medicine is based on the possibility of using stem cells to replace injured organs or tissues. The possibility to duplicate, to repeat oneself has replaced other forms of treatment like grafts and transplants. Plastic self-replacement has become the new paradigm.

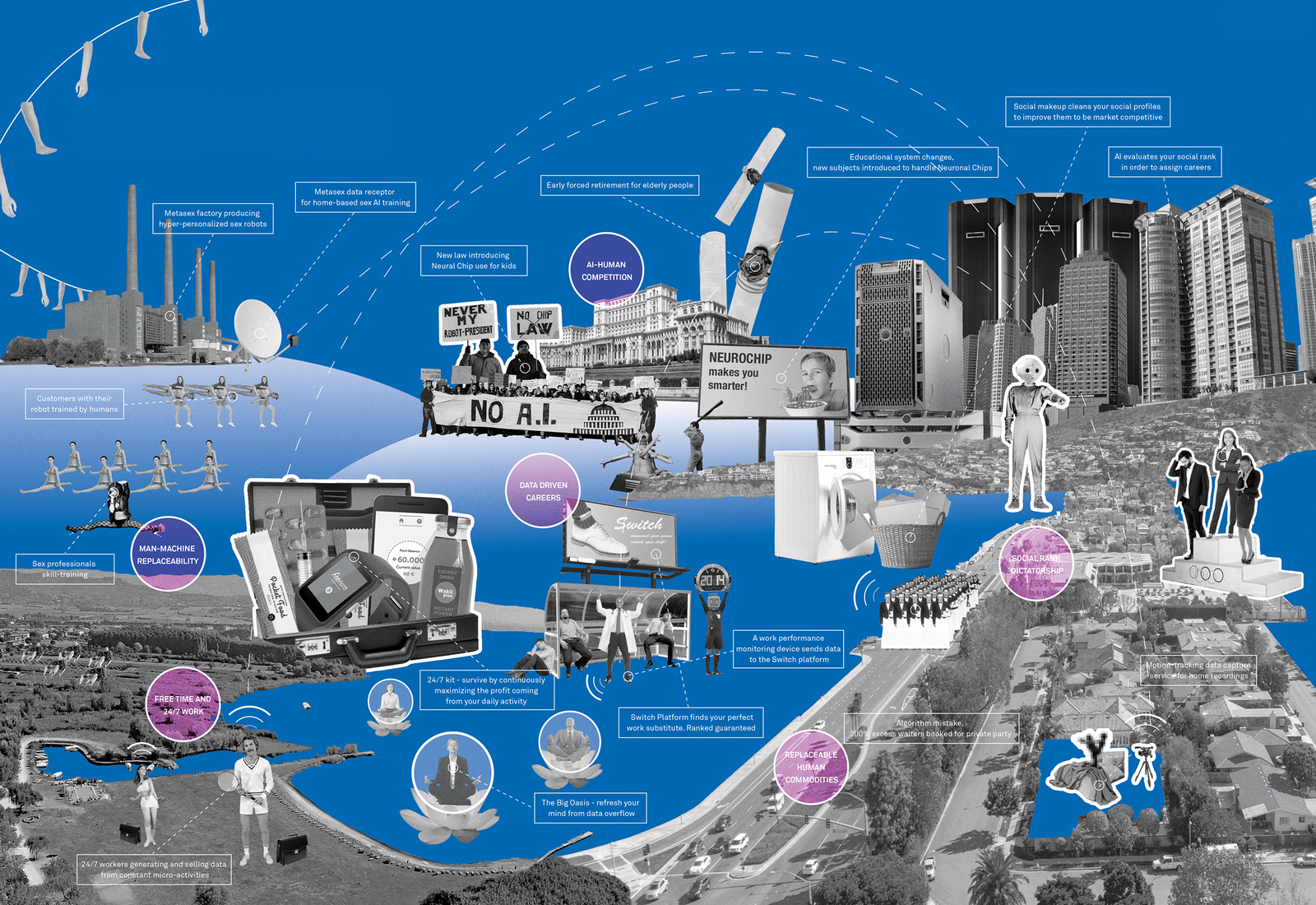

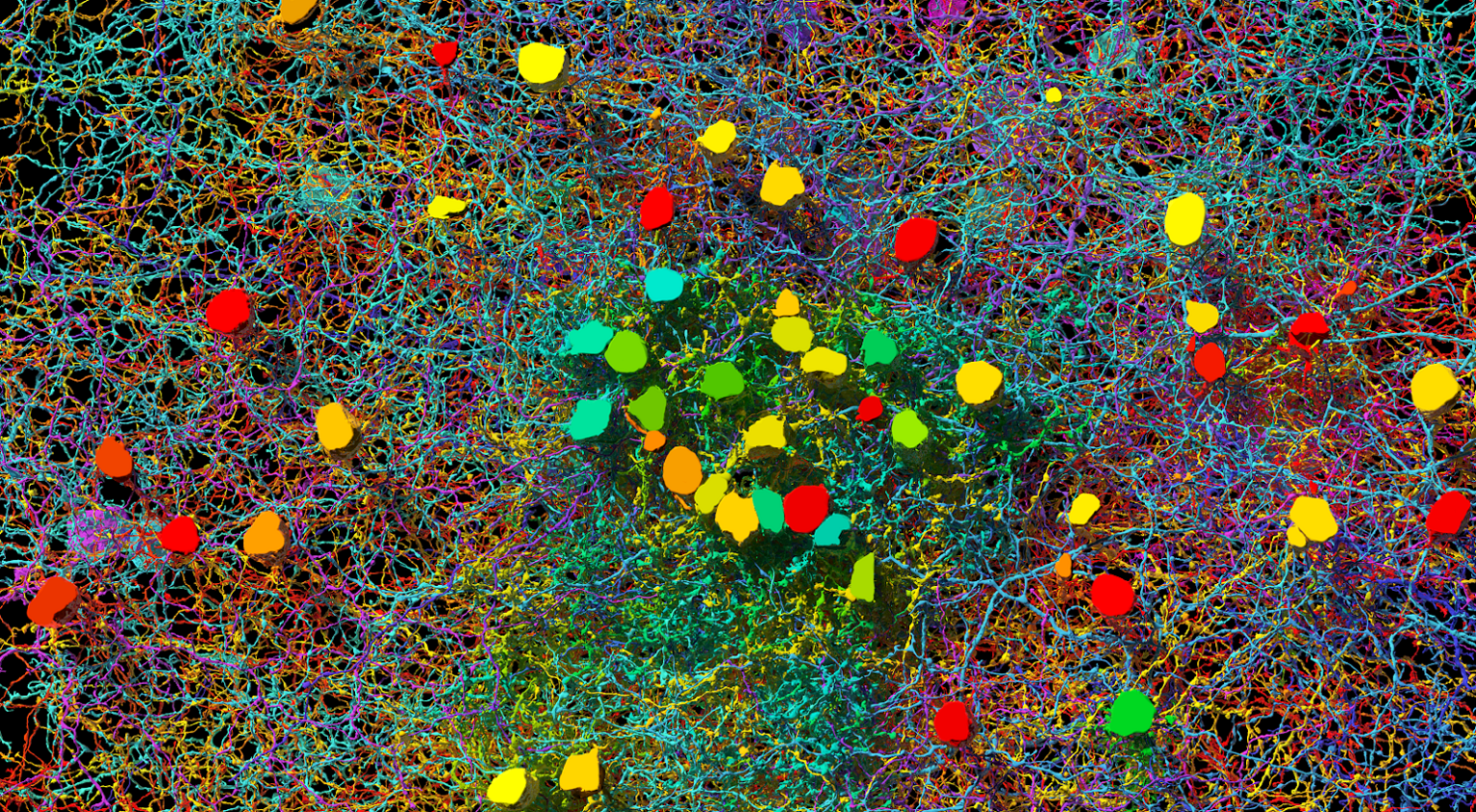

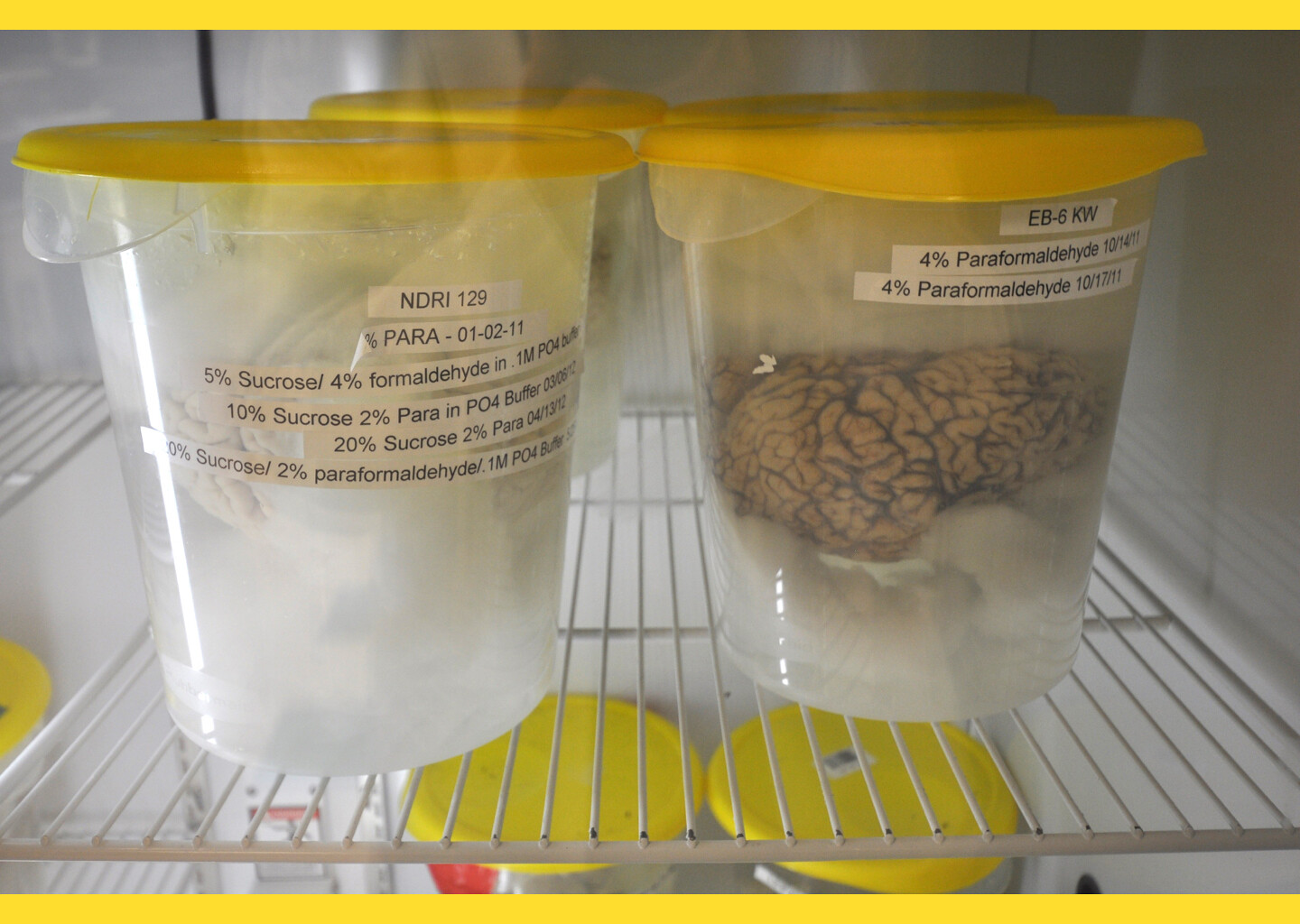

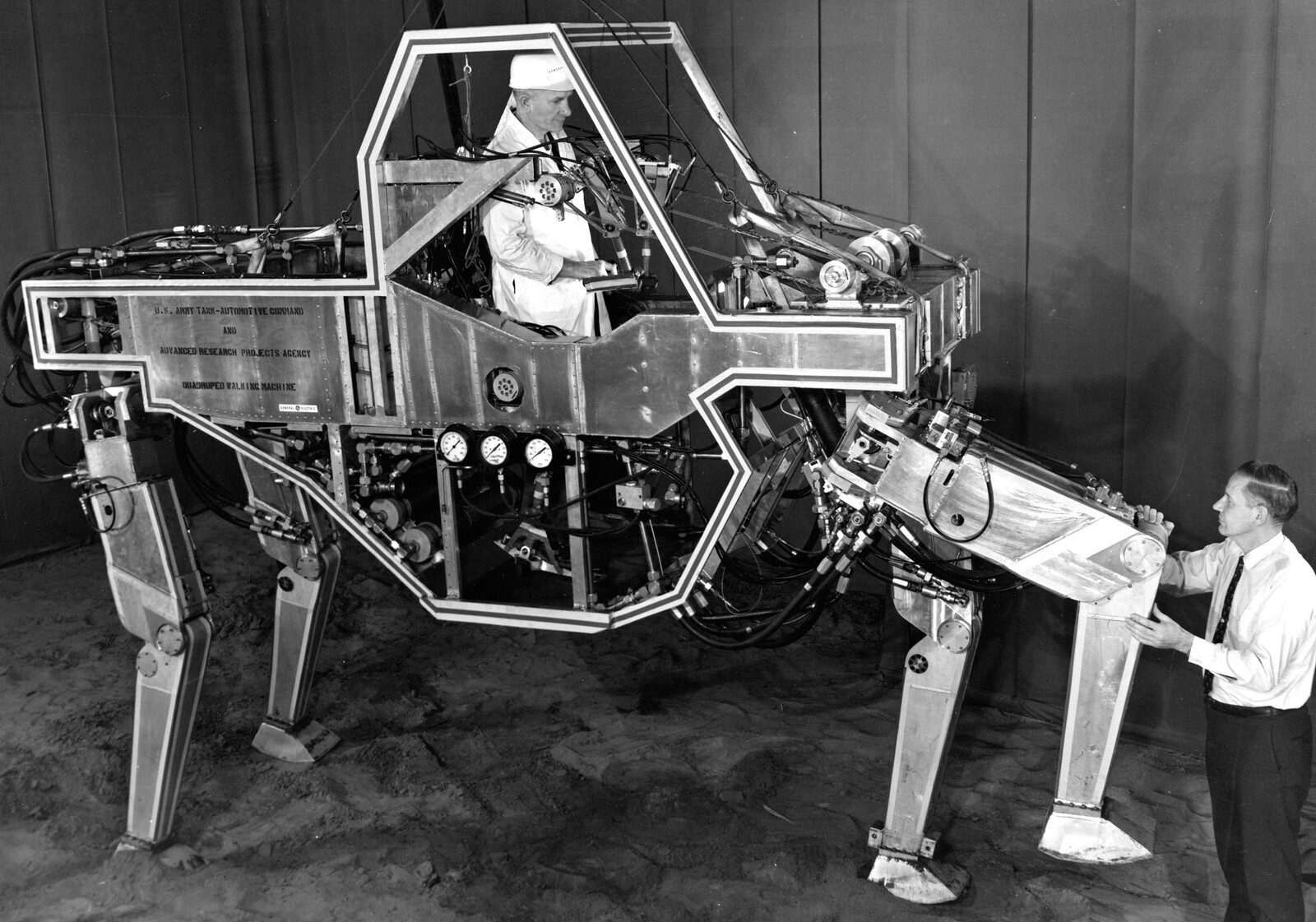

Artificial intelligence is another example, as its goal is to simulate, that is, to repeat, cognitive operations. I am referring here specifically to the Human Brain Project, a large ten-year scientific research project established in 2013 by Henry Markram.7 The Human Brain Project will develop information and communication technology platforms in six main areas—neuronformatics, brain simulation, high-performance computing, medical informatics, neuromorphic computing, and neurorobotics—with the aim of producing a complete and detailed cartography of the human brain. There are other major large-scale brain initiatives around the globe, such as the Japanese Brain/MINDS project, and the Korean Brain Research Institute, and others currently being planned in both China and Taiwan. As a recent report from one brain project puts it, “it takes the world to understand,” and also to simulate, double, and duplicate the functions of, “the brain.”8

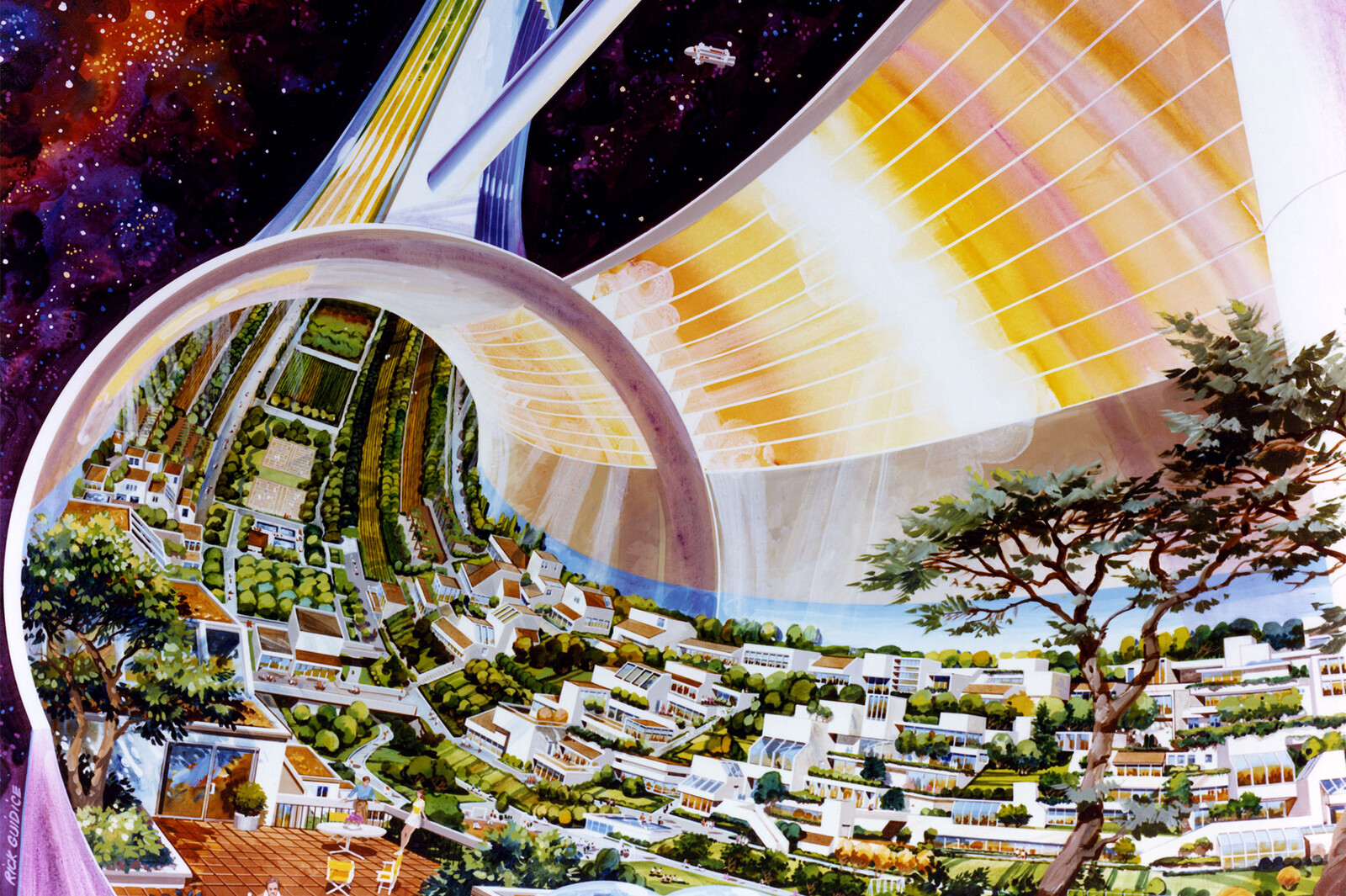

The issue raised by all these new occurrences of repetition is not, as we too often think, whether we are replaced or augmented by machines, as the post-humanists predict. It is rather the question of whether we are able to deal with this new urgency for repetition without seeking revenge against it or against finitude. Is the post-humanist claim that human beings will become amortal not precisely a sign of such a revengeful tendency? Are we, the superhumans to come, different from post-humans in being able to open ourselves to the future without developing hatred against time, without trying to crucify transiency and passage? Or in other words, is the plasticity that can currently be found everywhere—in aesthetics, medicine, ecology, physics, psychology, neurobiology—actually what it proclaims to be, or does it merely coincide with flexibility, that sham of plasticity? If plasticity entails the power to bestow form, flexibility only designates the capacity to be molded or bent in all directions without resistance. Will the superhuman be plastic, or flexible?

In a wide-ranging discussion on “the end of work,” Derrida cited The End of Work: The Decline of the Global Labor Force and the Dawn of the Post-Market Era by Jeremy Rifkin, which, he said, proclaims that a new revolution is “moving us to the edge of a workerless world.” In a certain sense, the idea of “post-labor” is a plastic occurrence, to the extent that it is the emergence of both a new form of life and a new form of the subject. Nevertheless, Derrida adds that this new form, which is presented as flexibility, entails the layoff of millions of workers, including, for example, “underpaid part-timers” at universities. Is the same crucial ambiguity between plasticity and flexibility at work in the aforementioned examples?

Returning to where we began—the search for an answer to the question of how it is possible to repeat plastically, how repetition changes and transforms what it repeats—we can look to Nietzsche again:

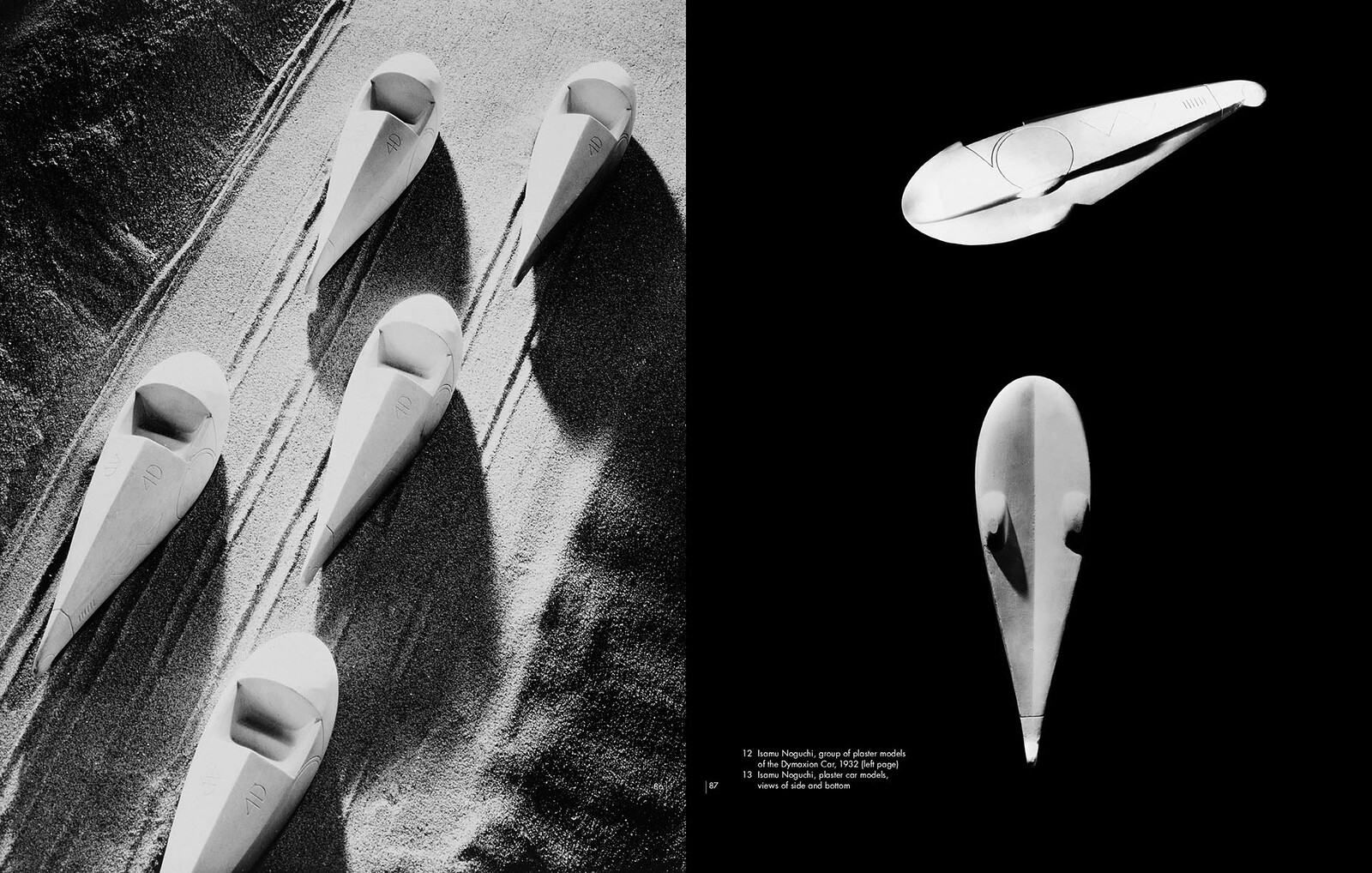

To determine this degree, and therewith the boundary at which the past has to be forgotten if it is not to become the gravedigger of the present, one would have to know exactly how great the plastic power of a man, a people, a culture is: I mean by plastic power the capacity to develop out of oneself in one’s own way, to transform and incorporate into oneself what is past and foreign, to heal wounds, to replace what has been lost, to recreate broken molds.9

“To develop out of oneself” and “to recreate broken molds” implies openness to what makes the routine of time explode, that is, the event. But do we really wish for the other to come? Beneath all of the technological novelties of our time, I am not sure “we” actually want novelty. Yet in the trembling openness of this question appears the possibility of sculpting the human to come, that creator of new genealogies, deprived of originary guilt, ready to play anew—that is, to repeat differently.

Jacques Derrida, “The Ends of Man,” in Margins of Philosophy, trans. Alan Bass (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1972), 112.

Friedrich Nietzsche, “On the Genealogy of Morals,” in On The Genealogy of Morals and Ecce Homo, trans. Walter Kaufmann and R. J. Hollingdale (New York: Vintage Books, 1989), II, §11.

Friedrich Nietzsche, “On the Tarantulas,” Thus Spoke Zarathustra, trans. R. J. Hollingdale (London: Penguin Classics, 1961), 123.

Ibid., 238.

Jacques Derrida, Pardonner: l’impardonable et l’imprescritible (Paris: L’ Herne, 2004), 544ff., 382.

Adult stem cells act as a repair system for the body, maintaining the normal turnover of cells in regenerative organs, such as blood, skin, and intestinal tissues.

The Human Brain project is the European Union’s version of the American BRAIN Initiative (Brain Research through Advancing Innovative Neurotechnologies), also referred to as the Brain Activity Map Project, President Obama’s 2013 program to map the activity of every neuron in the human brain by using Big Data.

Z. Josh Huang and Liqun Luo, “It takes the world to understand the brain,” Science 350, no. 6256 (October 2, 2015): 42–44.

Friedrich Nietzsche, “On the Uses and Disadvantages of History for Life,” in Untimely Meditations, ed. Daniel Breazeale, trans. R. J. Hollingdale (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1983).

Superhumanity is a project by e-flux Architecture at the 3rd Istanbul Design Biennial, produced in cooperation with the Istanbul Design Biennial, the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea, the Govett-Brewster Art Gallery, New Zealand, and the Ernst Schering Foundation.

Superhumanity: Post-Labor, Psychopathology, Plasticity is a collaboration between the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea and e-flux Architecture.