e-flux Architecture is pleased to announce the return of Superhumanity, in collaboration with the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea, with Superhumanity: Post-Labor, Psychopathology, Plasticity, featuring contributions by Chin Jungkwon, Common Accounts (Igor Bragado and Miles Gertler), Arisa Ema, Hong Sungook, Yuk Hui, Kim Jaehee, Catherine Malabou, Hannah Proctor, Erik and Ronald Rietveld, and Mark Wasiuta. Superhumanity: Post-Labor, Psychopathology, Plasticity will be published as a book later in 2018, in both English, by Actar, and Korean, by Moonji.

Post-Labor

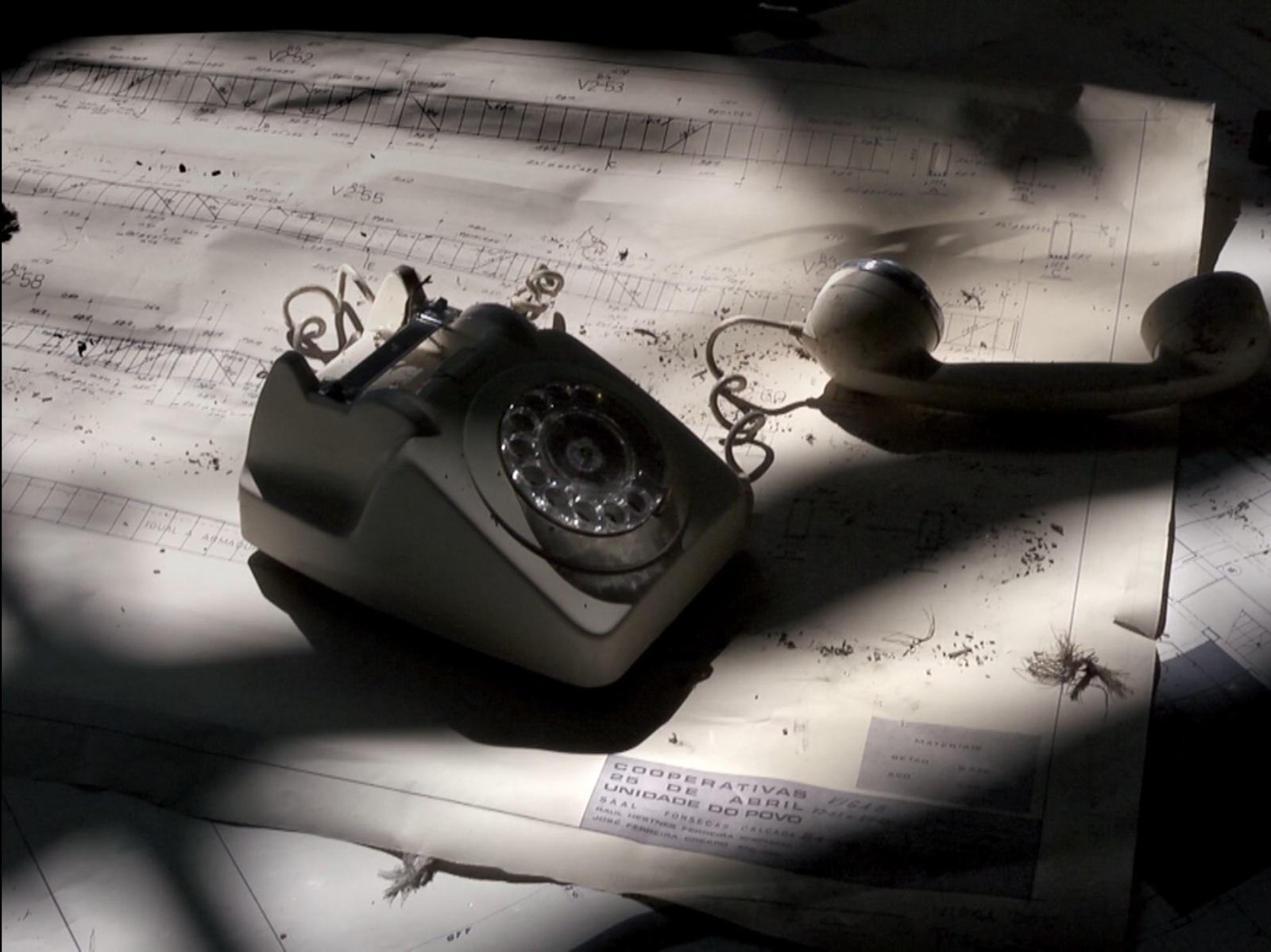

In his short text “Louis-Philippe, or the Interior,” Walter Benjamin wrote of the new split between work and home in the nineteenth-century:

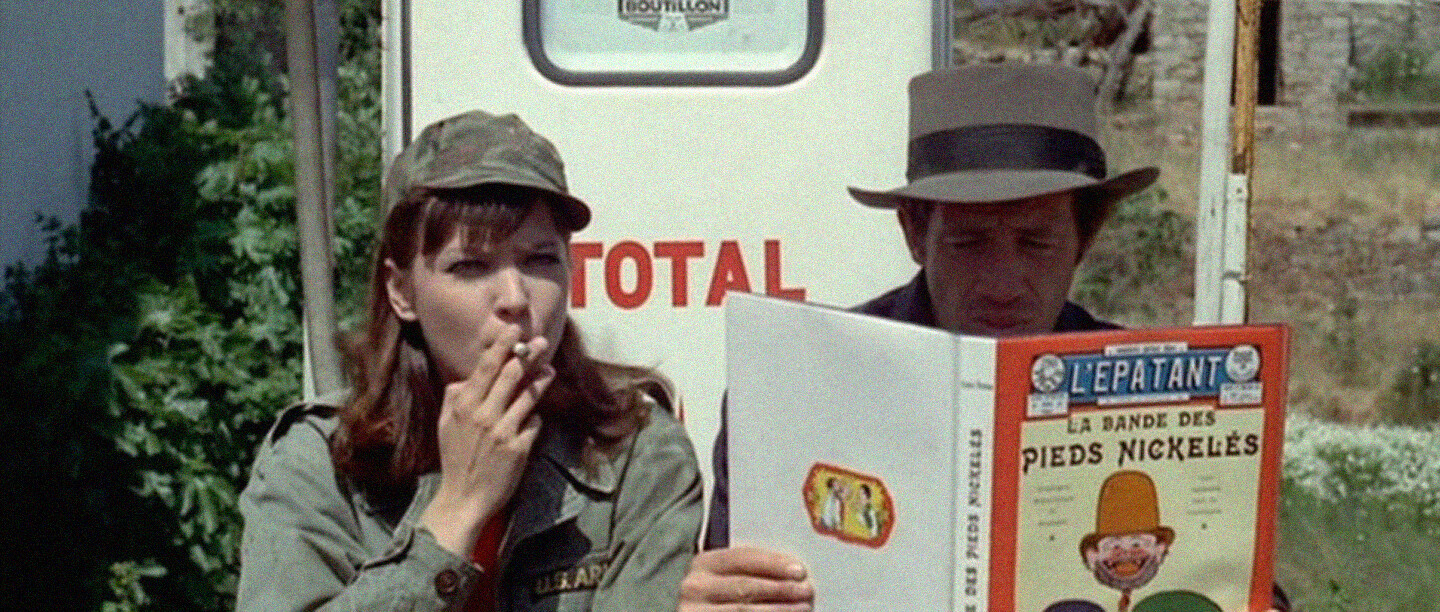

Under Louis-Philippe, the private citizen enters the stage of history… For the private person, living space becomes, for the first time, antithetical to the place of work. The former is constituted by the interior; the office is its complement. From this spring the phantasmagorias of the interior. For the private individual the private environment represents the universe. In it he gathers remote places and the past. His living room is a box in the world theater.

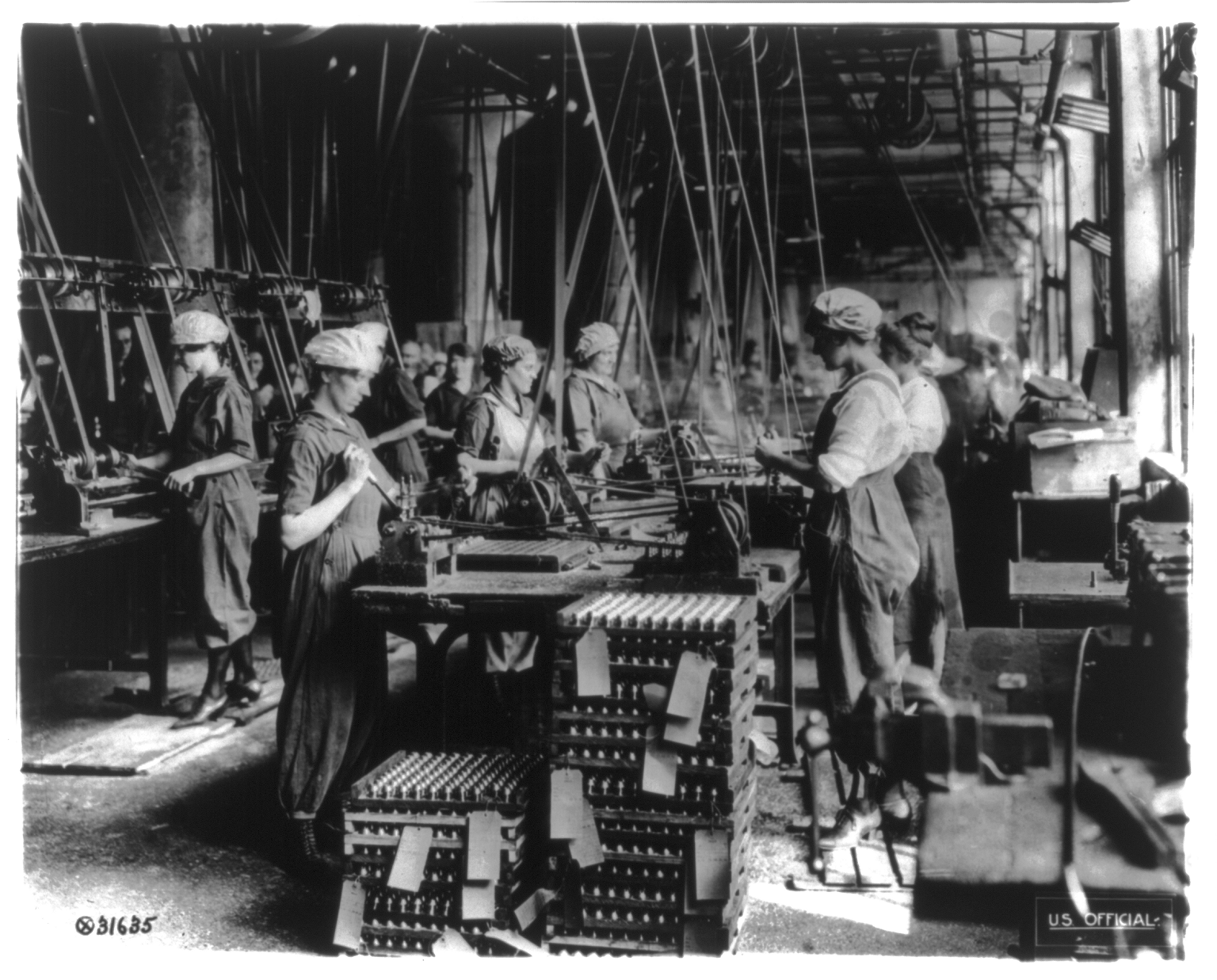

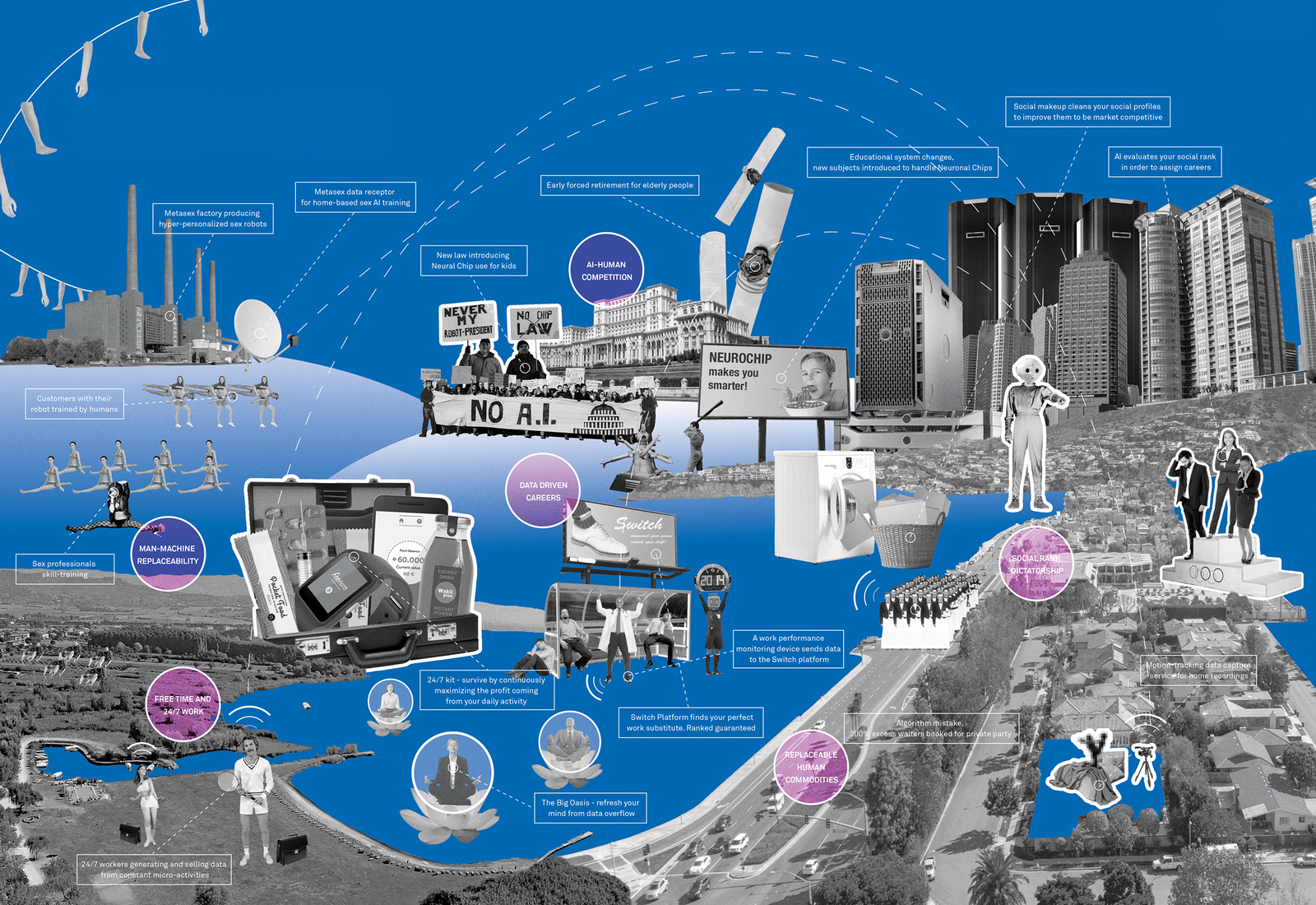

Industrialization brought the eight-hour shift and the separation of rest and labor, night and day. Post-industrialization has folded work back into the home, the bedroom, and even the bed itself. Already by 2012, more than 80% of young professionals in New York were working regularly from bed. Phantasmagoria no longer line the walls of private space, but are inside electronic devices. The whole universe is concentrated on a small screen. The bed floats in a sea of information. And as if in response, office spaces are being domesticated with sleeping pods. The bed has become the privileged site for global action. Or is it the beginning of withdrawal? With predictions about the end of human labor no longer treated as futuristic, a new horizontal architecture has taken over in a radical collapse of the distinctions between private and public, work and play, rest and action, sleep and labor.

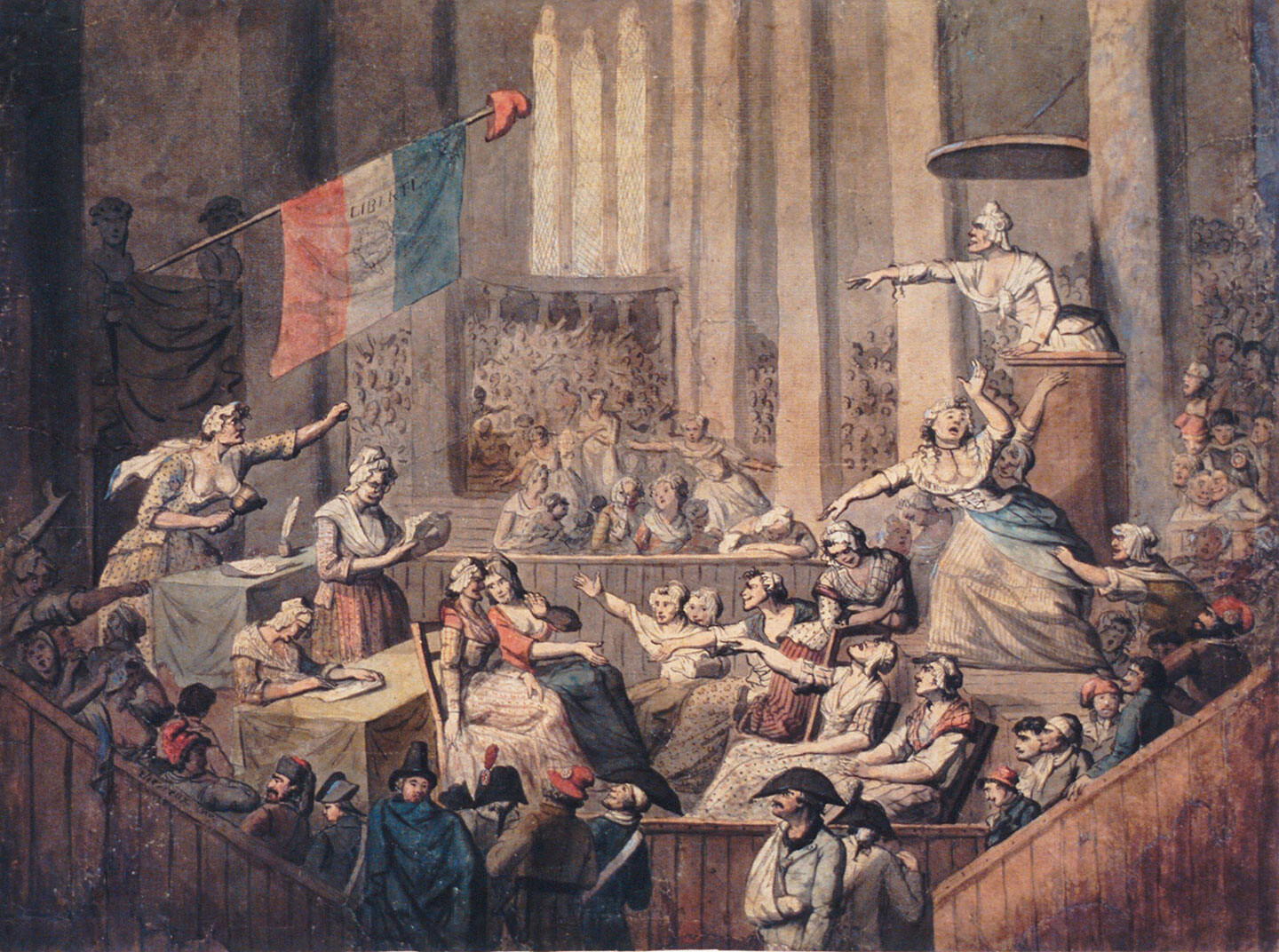

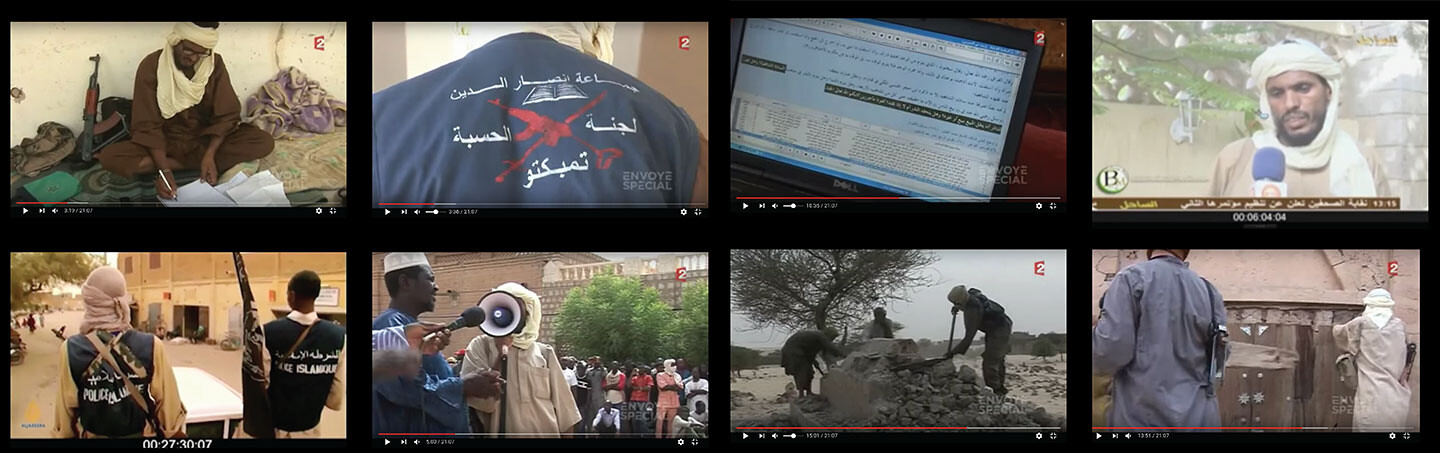

Psychopathology

“Every age has its signature afflictions,” writes Byung-Chul Han in The Burnout Society. We can add that each affliction has its architecture. The age of bacterial diseases—particularly tuberculosis—gave birth to modern architecture, to white buildings detached from the “humid ground where disease breeds,” as Le Corbusier put it. The age of smooth surfaces, big windows, and terraces to facilitate taking the sun and fresh-air cure ended with the discovery of antibiotics, and particularly streptomycin in 1943 (the first antibiotic cure for tuberculosis).

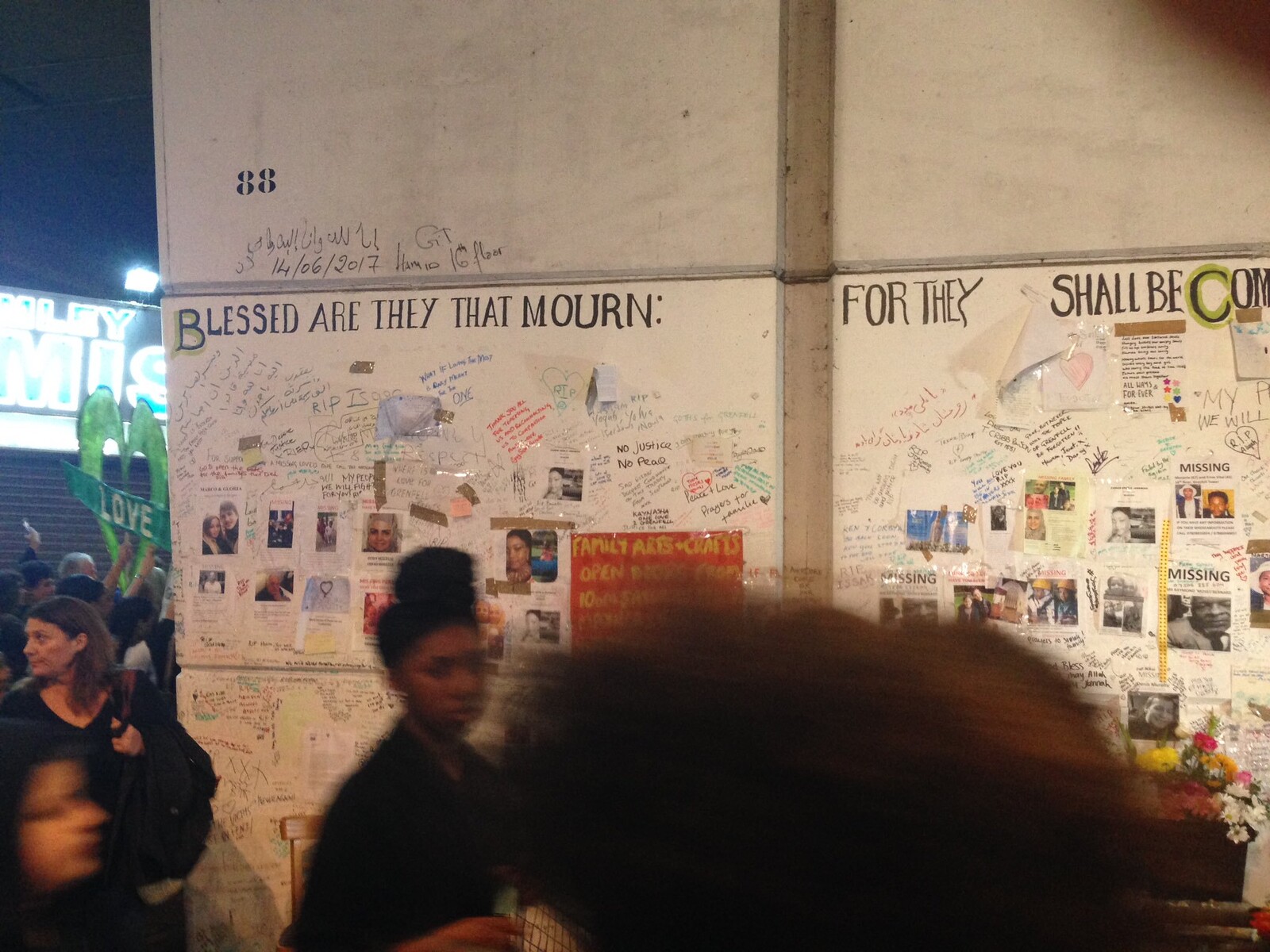

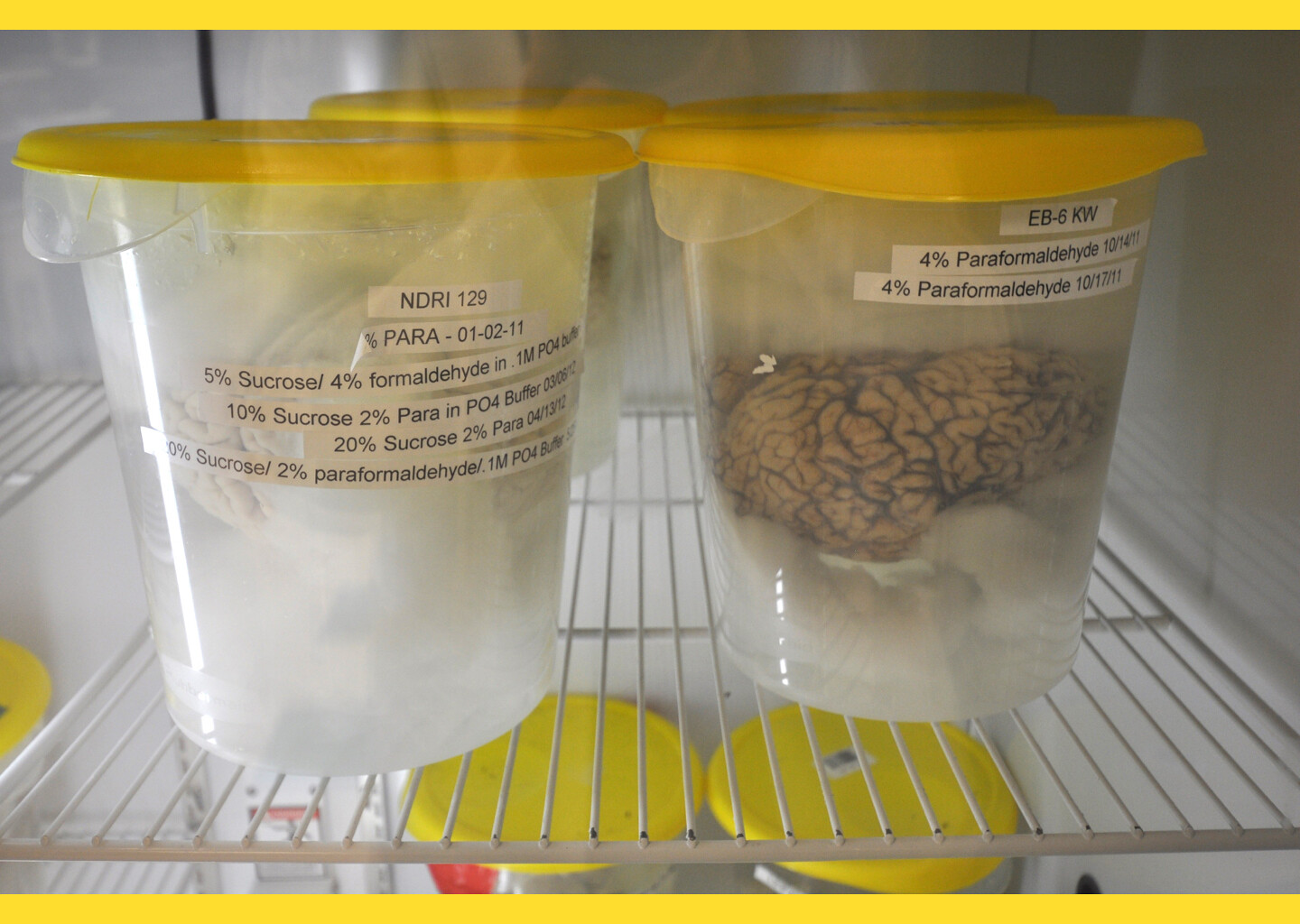

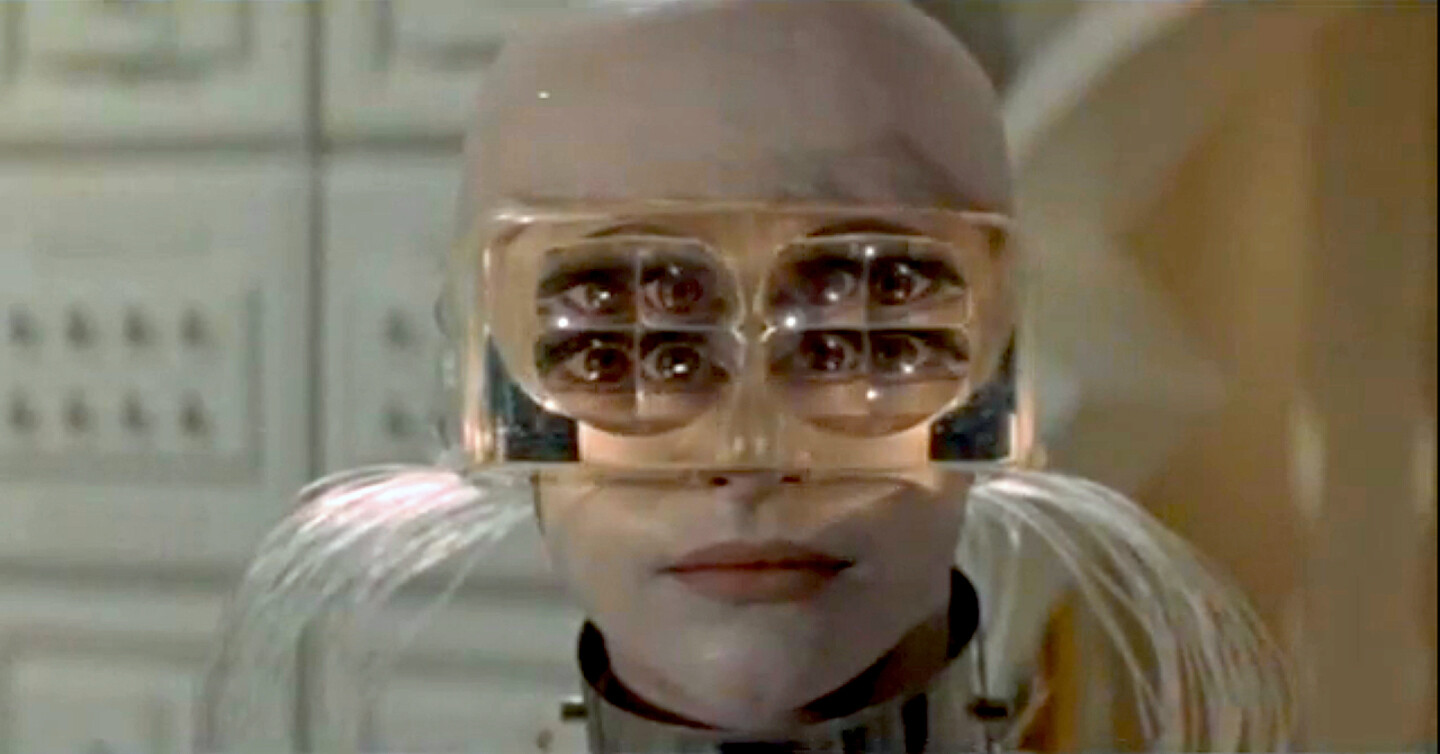

In the postwar years, attention shifted to the mind. The same architects who were once concerned with the prevention of tuberculosis became obsessed with psychological problems. The architect was not seen just as a doctor but as a shrink, and the house not just a medical device for the prevention of disease, but for providing psychological comfort, or what Richard Neutra called “nervous health.” The twenty-first century is, according to Han, the age of neurological disorders: depression, ADHD, borderline personality disorders, and burnout syndrome. What is the architecture of these afflictions? What do they mean for design?

The twenty-first century is also the age of allergies, the age of the “environmentally hypersensitive,” unable to live in the modern world. Never at any point in history have there been so many people allergic to chemicals, buildings, electromagnetic fields (EMF), fragrances… Since the environment is now almost completely man-made, we have become allergic to ourselves, to our own hyperextended body in a kind of autoimmune disorder.

Plasticity

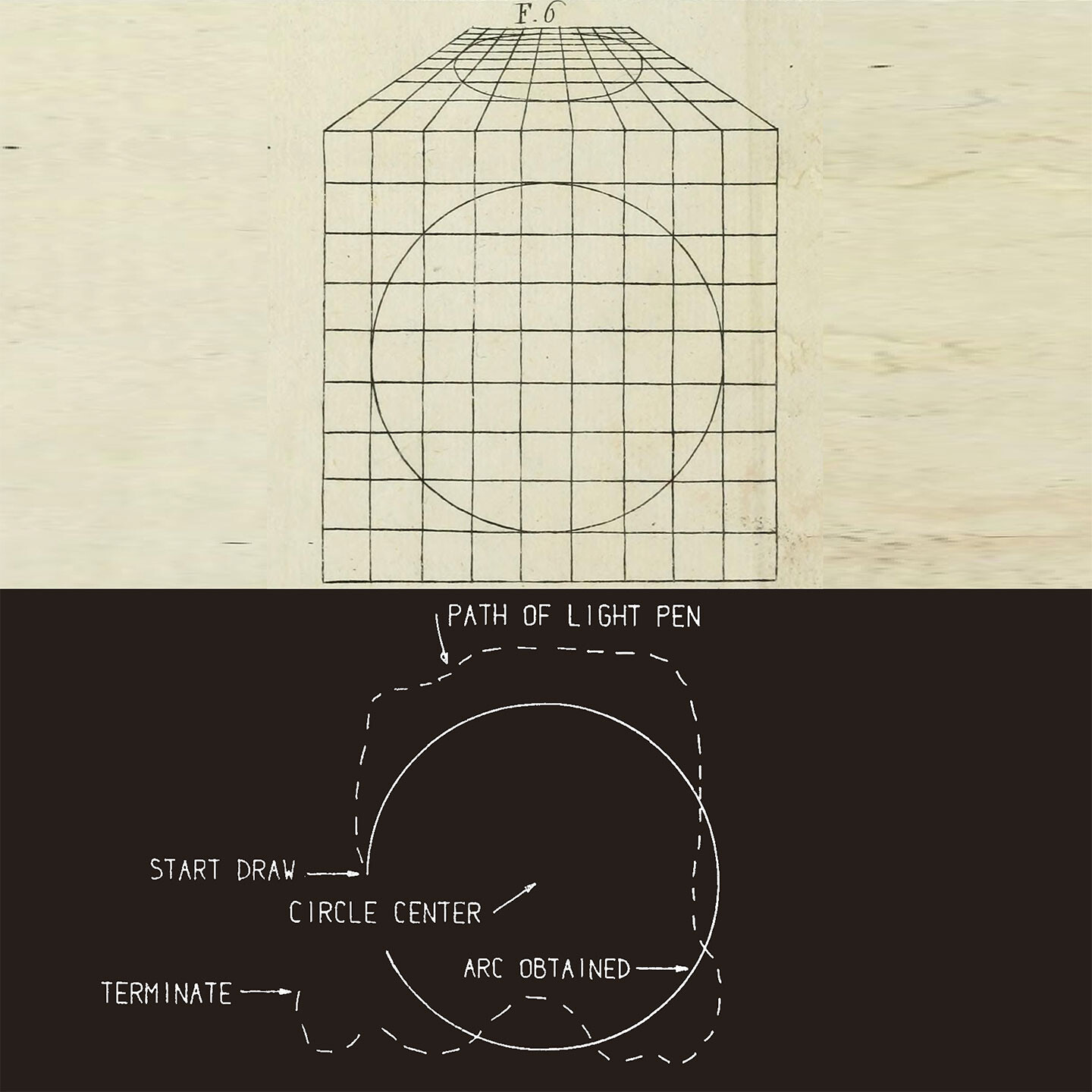

Beyond an artistic, architectural, and social movement that took place in the first decades of the twentieth century, constructivism is a philosophy of history. It believes, in short, in the present, yet counterintuitively: as something radically contingent. Habits, patterns, values, thoughts, and beliefs: while effusing an aura of permanence, none are fixed, nor are they necessarily desired.

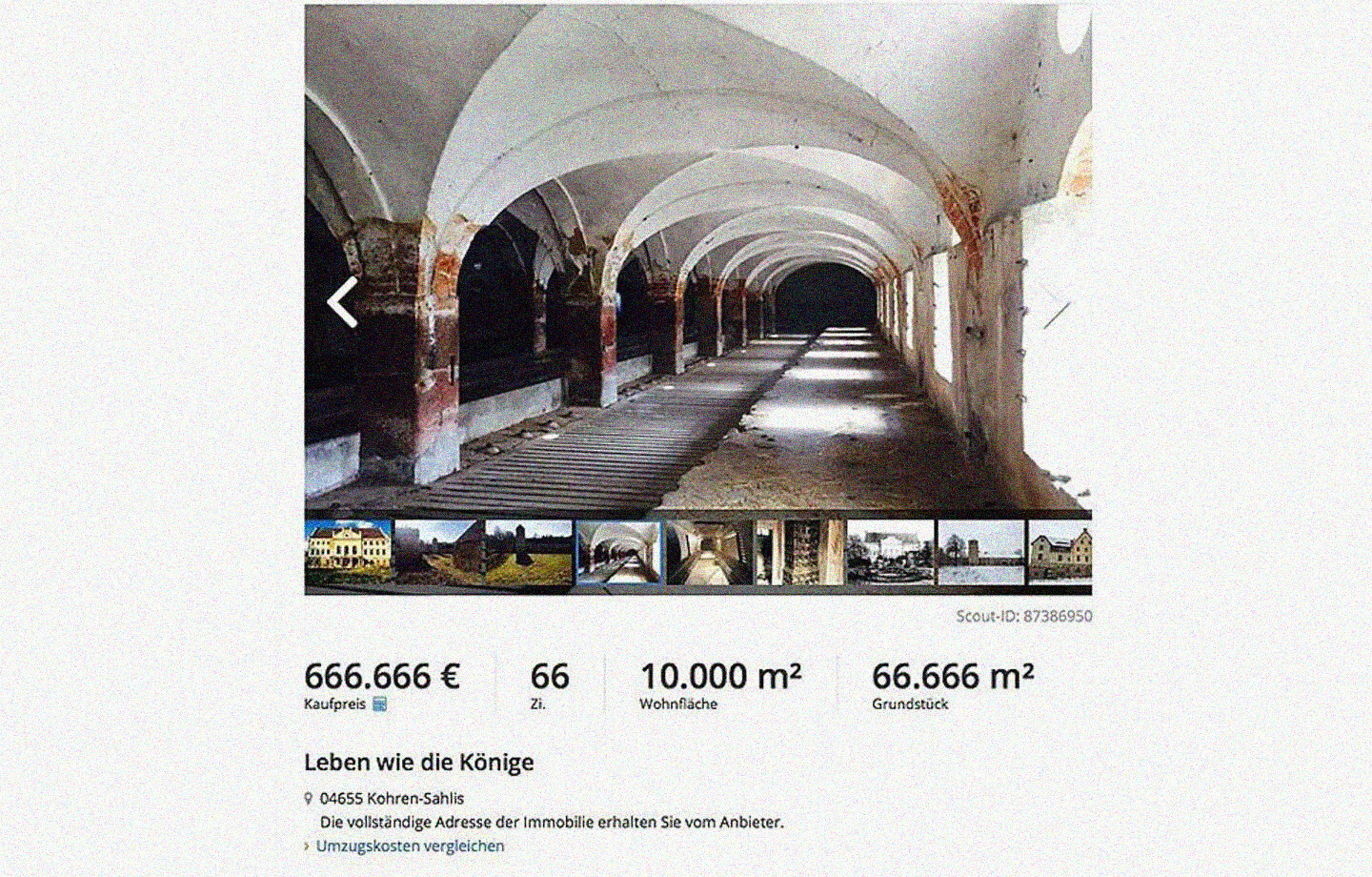

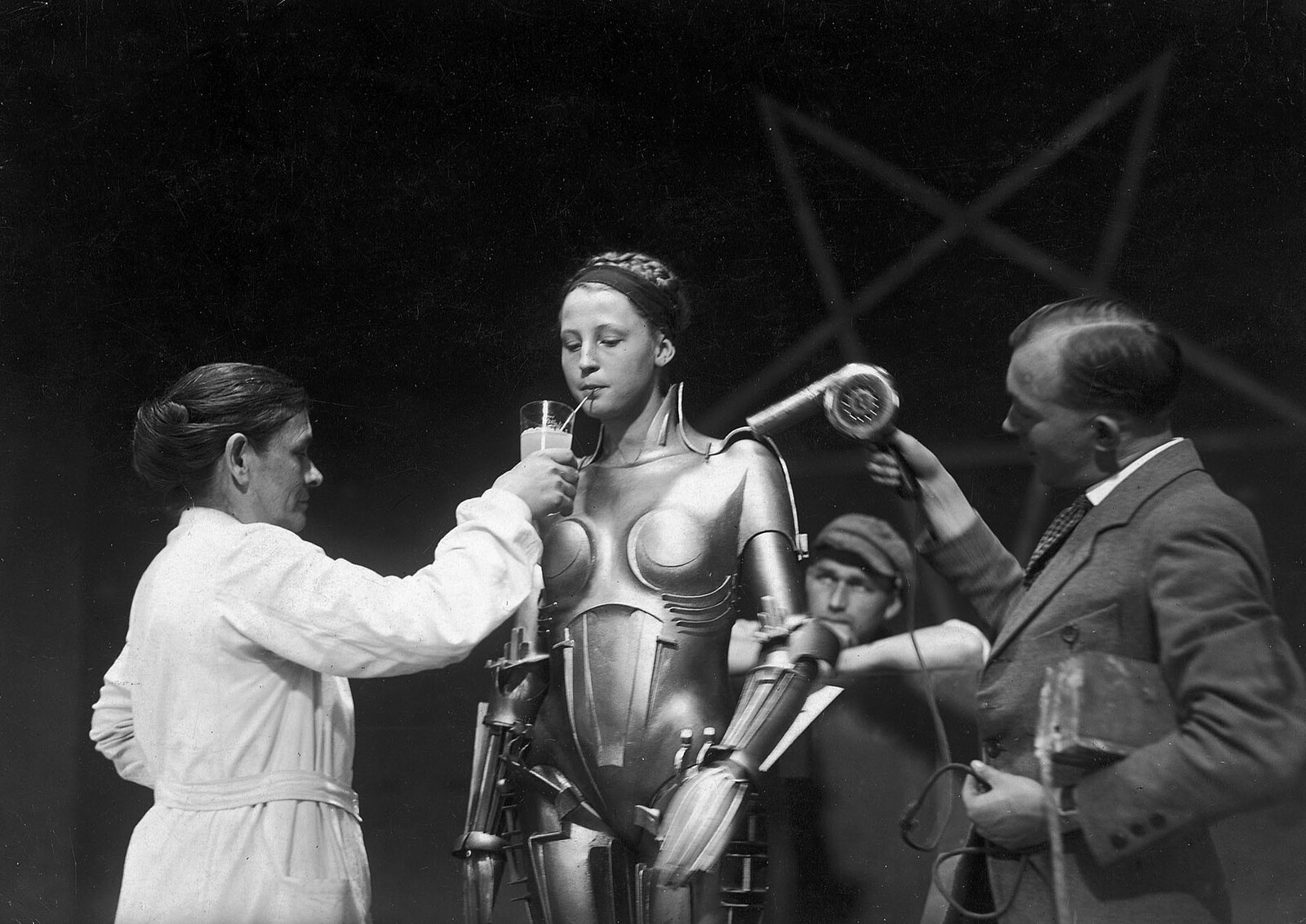

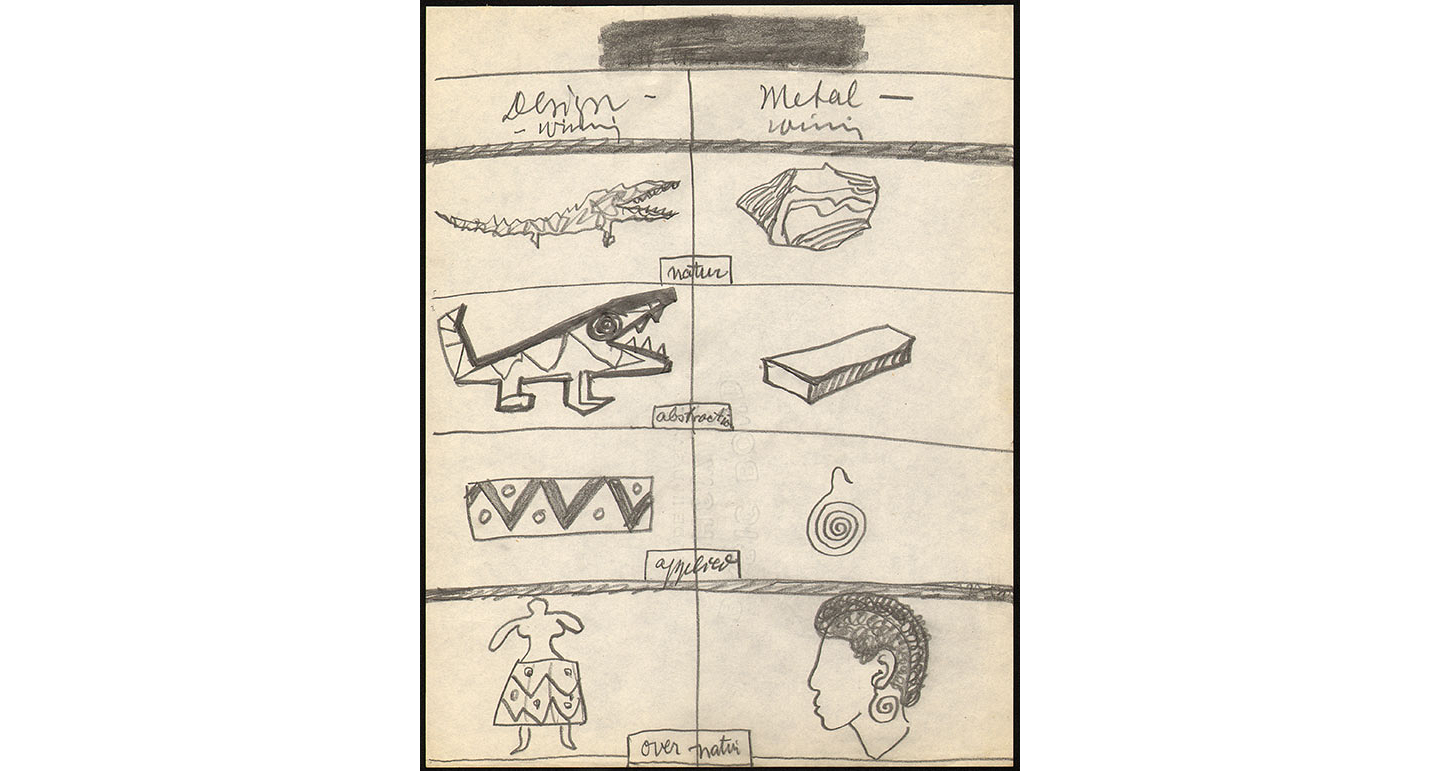

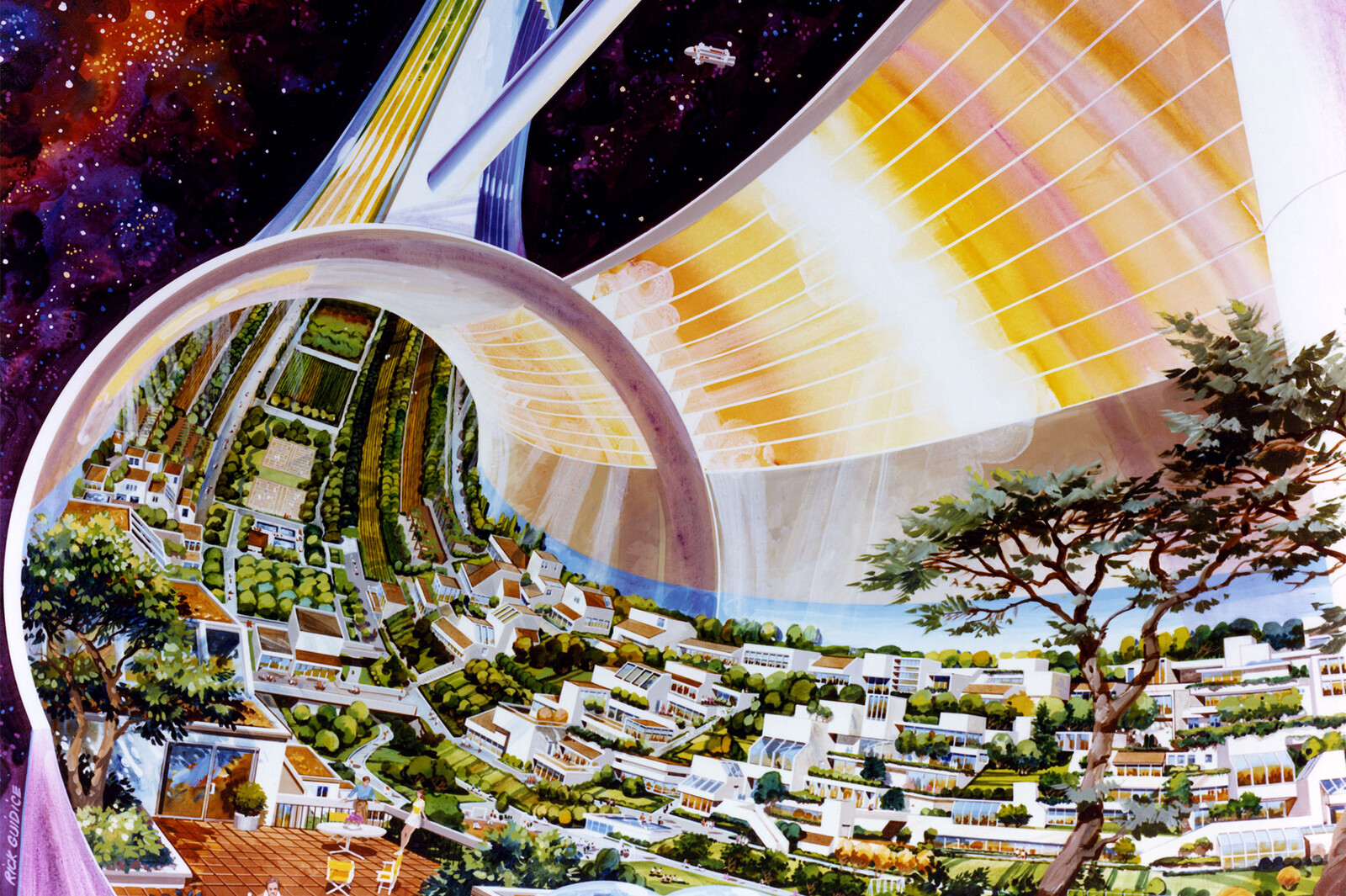

Constructivism is fundamentally humanist, in that takes the human itself, however it may be constituted, identified, or defined, as the ultimate object of design. It is in this sense that Soviet architecture—in conjunction with a massive state apparatus that allowed for the instantaneous and capricious geographical relocation and function reassignment of bodies—sought to dismantle patriarchal institutions such as the nuclear family and gendered labor by creating housing with kitchenless residential units as small as seventy square feet in size; an area too small for anything more than just one person.

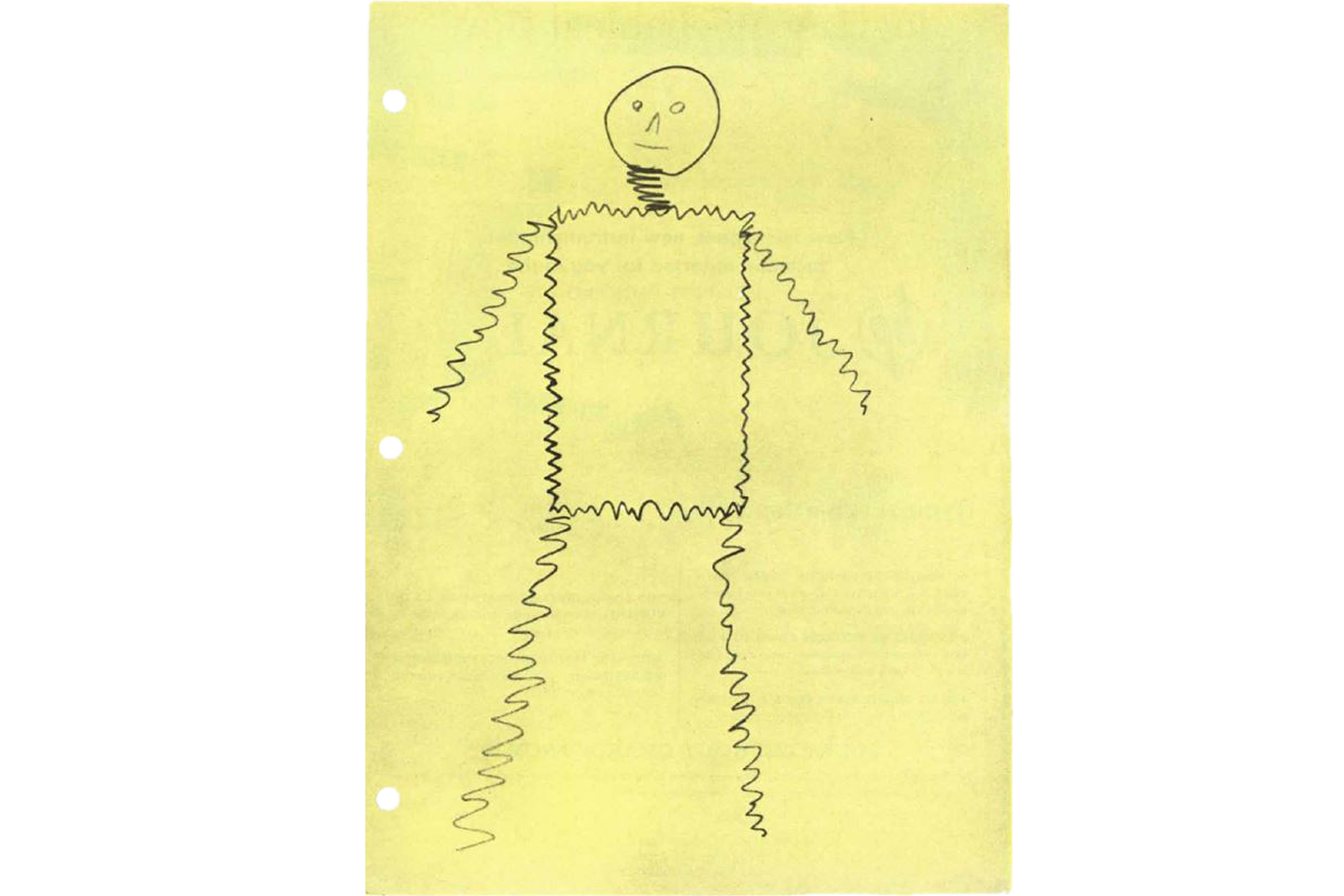

The human is, if nothing else, plastic. It changes, and as much as we might like to believe otherwise, that change most often comes not from within, but without; from the spaces and climates we live in to the objects, information, and people, we surround ourselves with. The question of the human is not just a question of what it is, but what it can, and should be. Design cannot help but design the human, and the human cannot but help design. Design is—design must, therefore, be the answer. So what, in the famous words of Cedric Price, is the question?

Superhumanity is a project by e-flux Architecture at the 3rd Istanbul Design Biennial, produced in cooperation with the Istanbul Design Biennial, the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea, the Govett-Brewster Art Gallery, New Zealand, and the Ernst Schering Foundation.

Category

Subject

Superhumanity: Post-Labor, Psychopathology, Plasticity is a collaboration between the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea and e-flux Architecture.