Today, most public officials and policy think tanks across the United States conceptualize the lack of affordable housing—and the related issue of socio-economic inequality—as a problem of supply.1 If only we produced more housing, the reasoning goes, the price of all housing would come down, which in turn would resolve some of the issues of inequality. This call for more production is often coupled with a call to reduce zoning or labor regulations, which, the argument goes, restrict density and drive up cost. That said, they are rarely coupled with a call to limit the profits made in housing, whether directly governmentally subsidized or not, and to make sure access to the new housing is fair.

Policy makers who attempt to use housing programs to address socio-economic inequality face a basic conundrum. On the hand, having a place to sleep is not only a non-negotiable need, but the location of where you sleep largely determines your access to key services and opportunities, like education and employment. Hence the “housing first” movement in addressing homelessness: Once you are stable and have a place to live, research shows, you are more likely to be able to take control of other dimensions of your life. On the other hand, housing alone cannot resolve socio-economic disadvantages. What good is a new apartment if you don’t have a job? What good is a cheap place to live if the nearby school sucks? This is the basic conundrum of housing policy as it relates to socio-economic opportunity: It is both essential, and yet only one part of what it takes to ensure an adequate life.2

New York City serves as an example of this disconnect between the call for more production and the socio-economic aspects of this production. At the beginning of his second term, Mayor Bill de Blasio proudly announced that his administration was increasing its goal of affordable housing production from 250,000 to 300,000 units.3 He did not address the fact that his or his predecessors’ production programs have had little effect on stemming the overall rise in housing costs or the surge of homelessness. This is not to say that governments should not be concerned about housing production, but rather to insist that the price of housing as the result of too little production is unconvincing.

By focusing on production as the solution to the lack of housing affordable to those who cannot pay market prices, this discourse also prevents a frank discussion of the connection between low-cost housing and low-quality services. The desirability of housing (reflected in its price) is largely shaped by the quality of the public services (schools, police, transportation) and economic opportunity (jobs) accessible via that housing. This is why even a self-declared progressive like de Blasio has, to date, avoided addressing the fact that his city’s public schools are among the most racially and economically segregated in the country, arguing instead that this is the inevitable result of housing, of where people live.4 Solving the interconnected issues of unaffordable housing and inadequate public services, and the resulting lack of socio-economic opportunity, would require an approach far more coordinated and comprehensive, and likely much more complicated, contentious, and conflict-ridden than housing production alone.

Indeed, previous policy makers have proposed just that. In January 1966, US President Lyndon B. Johnson launched a program that would become known as Model Cities, and housing was only one part of its tool kit. Model Cities was driven by the urgency to address the racialized disparity between the poverty of the nation’s older cities and the prosperity of its newer suburbs—a tension that was becoming increasingly apparent in the repeated rebellions taking hold of what was then referred to as “the ghetto” since 1964.5 The program aimed to show that by coordinating federal programs for social, economic, and physical renewal in close cooperation with residents, clearly defined target areas—low-income and generally majority-minority neighborhoods—could be “turned around” within five years.6

Model Cities was signed into law in November 1966. “Comprehensive” and “coordinated” were, at the time, the program’s key conceptual terms. They implied that change needed to address all aspects of residents’ lives—employment, health, education, political empowerment, and more—and not just the physical aspects of their living condition. Accordingly, federal money was to be given in “non-categorical” grants to municipalities, where officials and residents, involved through “widespread citizen participation,” would decide on how to spend it. However, by making relatively large sums of federal money available for citizen-defined initiatives, Model Cities caused as much instability as it sought to remedy. Implementing the program tipped the balance of power not only amongst citizens, city hall, and city bureaucracies, but also prompted conflict among the multiple constituencies that made up any one Model Cities Neighborhood. Addressing the complexity of power relations in many places shook things up to the point of collapse. In 1974, President Richard Nixon terminated Model Cities due to a lack of tangible deliverables. Both analysts at the time and historians since have largely abbreviated the program as a failure.7 But we could also understand Model Cities to have been highly productive, precisely due to the instabilities it triggered in aiming for all-encompassing change.

In New York City, Model Cities played out and intersected with the production of housing and the discourse of architecture in three distinct phases. The first was a municipal housing program launched in mid-1966. In the language of the time, this “physical” program was to be only the first step toward the comprehensive program. The program would place equal if not stronger emphasis on the so-called “social” components of urban life, including education, health care, job creation, and more. The second phase began with approval of the first federal grant to New York City in late 1967. At this point, figuring out precisely what “widespread citizen participation,” as stipulated by the law, meant, led to protracted conflicts between local communities and central city authorities. Ultimately, fighting about who would control resources and decide on how they would be spent resulted in the stalling of many programs, even ones that had been approved by the federal authorities. The third phase, which began in early 1970, was characterized by a centralization of control in city hall. Under intense pressure to deliver results, city hall shifted Model Cities funds away from hard-to-realize social programs like job creation and education, and toward easier to control projects, mainly housing. With this shift, the original comprehensive aspirations were abandoned.

New York City’s shift in priorities toward physical production post-1970 was a boon to housing and architecture—as can be seen by the various design and development models that were tested at the time. But the focus on physical production was not good for Model Cities’ original, comprehensive approach to “improving the quality of life” in cities: the physical ended up trumping the social and the economic. This is the persistent conundrum that is inherent in all efforts to make cities more equitable—meaning accessible and affordable to all—through increasing the supply of housing. It continues to bedevil New York City, fifty years after Model Cities was conceived. But today, the tables have turned in the sense that the main concern of residents of low-income neighborhoods is displacement not through disinvestment, but through gentrification. This struggle can be witnessed in some of the very same areas targeted by Model Cities half a century ago, including Mott Haven in the Bronx, East Harlem in Manhattan, and East New York in Brooklyn. But the City mayor’s response is, once again, more housing construction, rather than a comprehensive approach to addressing inequality.

Writing about Model Cities invariably means touching on the methodological challenge of analyzing a program whose products are remarkably difficult to identify. Model Cities generally contributed only gap funding to its initiatives. As such, many of its most tangible outcomes, including housing, are rarely traced to their origin, and doing so requires a concerted effort to connect dispersed pieces of evidence. If projects were published at the time, authors rarely mentioned the origin or funding sources connected to Model Cities. Other evidence has been lost or is difficult to access.

But in the search for the traces of what was debated, decided, and acted upon, it is possible to find potent exceptions: in early 1968, New York City’s central Model Cities Committee commissioned documentary filmmaker Gordon Hyatt to document the community participation processes and shed light on the program’s goals and methods.8 It is unclear who the intended audience of this production would be, but very likely the idea was to have a tool to easily communicate the basic goals, structure, and results of Model Cities to the general public. The production, later titled Between the Word and the Deed, involved five cameramen filming over a period of two years. The sixty-minute film was delivered precisely at the moment when the program was reorganized and key staff replaced; the original enthusiasm for the program had already waned, and the film was never shown publicly. Seen more than forty years later, the film provides invaluable insights into how the first years of Model Cities were negotiated on the ground. It also serves as a stark reminder as to the ephemeral nature of learned knowledge as cities continue to face issues of systemic racism, spatial segregation, and economic disparity.

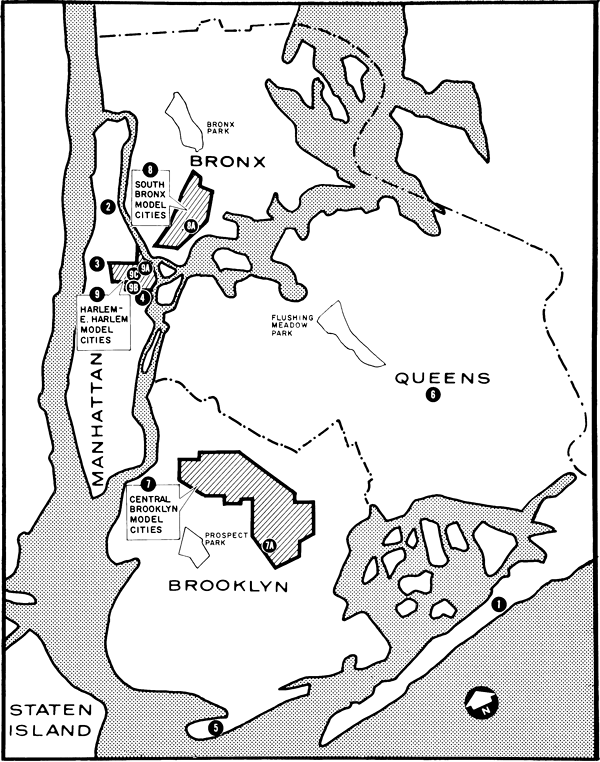

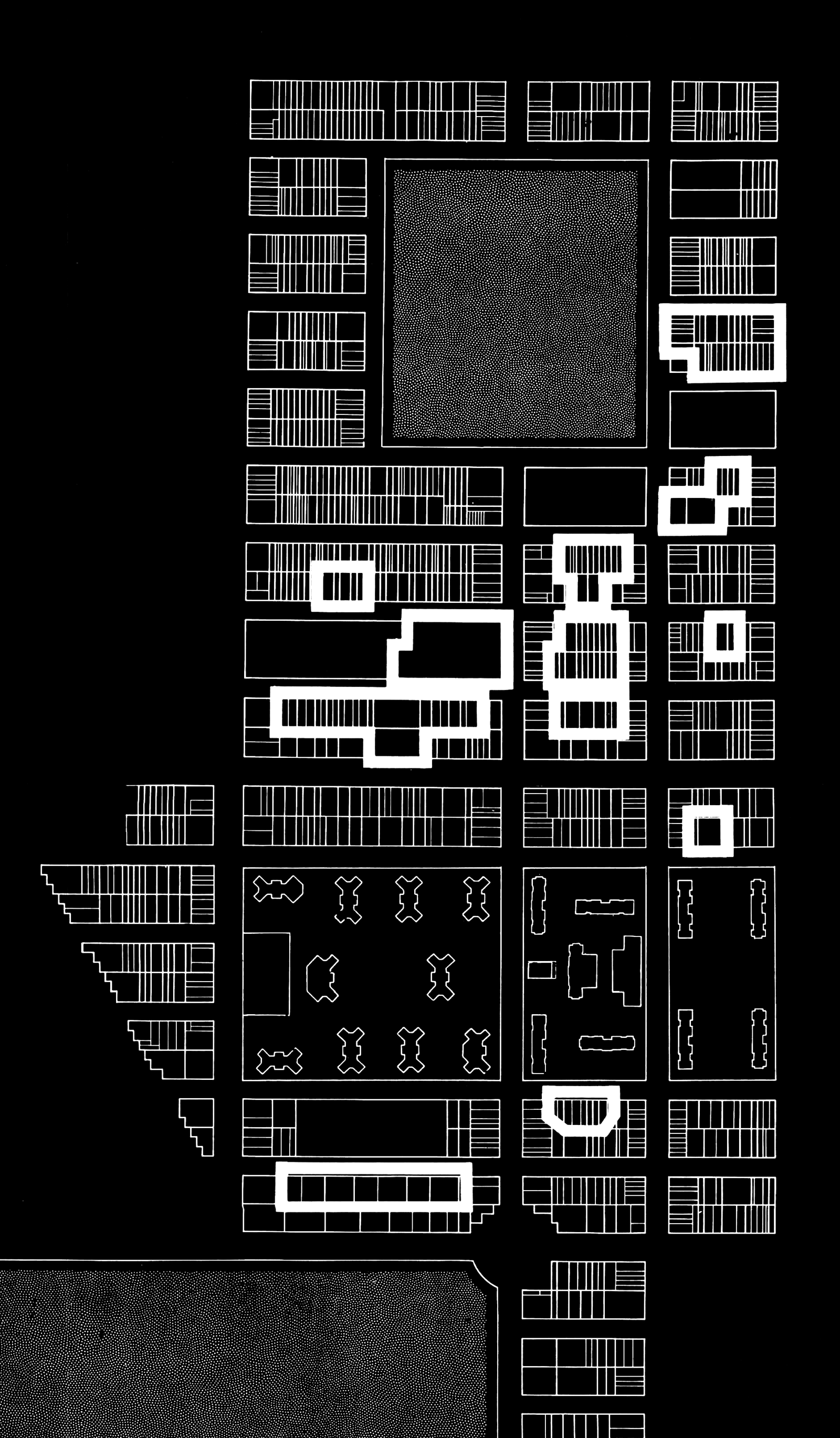

Map indicating the location of Model Cities and Urban Renewal areas, from The City of New York, Community Development Program: A Progress Report, December 1968.

1. 1966–68: A “comprehensive” program with “widespread citizen participation”

The Demonstration Cities and Metropolitan Development Act, as the Model Cities program was originally called, was conceived as a corrective to two existing federal urban programs. The first was urban renewal, a federal land write-down program on the books since 1949, which had subsidized cities’ slum clearance and rebuilding efforts, and had rarely benefitted the poor who were displaced through such clearance. The second was the Community Action Program (CAP), which since 1964 had channeled federal money directly to community groups to use toward social services and local programs. Coordinated by the federal Office of Economic Opportunity, mayors disliked CAP since the funding bypassed elected officials. Moreover, many claimed that the program was contributing to civil unrest, not mitigating its causes.9 In contrast, the new experimental program was to address not only construction—as urban renewal had—but also education, job training, health, and so on, in an attempt to serve the people who had previously been in danger of displacement. Its money was not to be given directly to local communities, but rather flow through existing city bureaucracies. Besides an emphasis on the “comprehensive,” the program was innovative in how federal funding would be delivered to the participating cities: flexible, “non-categorical” grants could be allocated by citizen committees to anything from mobile health clinics and job training programs to summer camps for school children or start-up loans for local entrepreneurs.

Given the double meaning of the term “demonstration”—an experimental project on the one hand, and urban conflict on the other—by the time the program was passed into law in November of 1966, its name had been changed to the more benign “Model Cities.” But the confusion between the two terms would continue to shape the perception of the program. On the one hand, there is the normative sense of “model,” as producing ideal outcomes to be emulated by others, and inevitably associated with the moral sense of the term, as in “model citizens.” On the other hand, there is the more open-ended meaning of “demonstration,” as testing a hypothesis through an experimental process. As late as 1972, an official found it necessary to clarify that Model Cities was not about producing “shiny new cities,” but rather to show that “conditions … could be significantly improved.”10

Newly elected New York City Mayor John Lindsay supported and enthusiastically anticipated the new federal program. In June 1966, even before the program was signed into law, he launched a “vest pocket housing and rehabilitation” program as a “head start” to more comprehensive planning efforts. The term “vest pocket” referred to smaller than full-block, infill sites, and the design of the new housing was to depart from “stereotyped” towers that had been “designed in a vacuum of participation.” This was an explicit reference to post-war urban renewal practices, which had generally created so-called tower-in-the-park superblock developments.11 In November 1966, Lindsay engaged five planning consultants to work with committees of local residents with the specific task of siting 800 units of low-income public housing, and 800 units of moderate-income nonprofit-sponsored housing in five target areas: East New York and Bedford-Stuyvesant, Brooklyn; Harlem’s Milbank-Frawley Circle, located on the northeastern corner of Central Park, Manhattan; and Mott Haven and Twin Parks, the Bronx. With the exception of Twin Parks, the studies were seen as only a kernel of the future planning efforts for the much larger Model Cities Areas designated for the South Bronx, Harlem-East Harlem, and Central Brooklyn.12

The resulting proposals were remarkable in their diversity. They ranged from new mid-rise buildings that sought to create urban markers within existing block structures (Twin Parks) and strategies privileging recreational spaces in the block interiors (Mott Haven) to resident-controlled housing ownership and management (East New York), further development of the brownstone type (Bedford-Stuyvesant), and even feedback-loop software to calculate the best possible use of any one site (Harlem).13

The plans provided the basis for the city’s application for a Model City “planning grant” in July 1967. It was submitted just as a new wave of urban conflict erupted throughout the country, most prominently in nearby Newark, New Jersey. New York’s proposals were approved by the US Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) in November of that year. The grant would enable the formulation of a second application, this one for the implementation of programs. For this second proposal, which was due in mid-1969, HUD required detailed proposals not only for the program area of Physical Development—which included housing—but also for the program areas of Education, Economic Development, Sanitation and Safety, and Health Services. Goals were to be formulated in partnership between local committees of residents and city authorities.

2. 1968–69: Conflict

By mid-1968, a year after the Model City planning grant application, the political and economic situation in the nation’s cities had only gotten worse. The war in Vietnam had taken over political discourse, and its rising costs led to a fight over how limited public resources for domestic programs such as Model Cities were to be allocated. In March 1968, President Johnson announced he would not seek reelection that November, and only a few weeks later, civil rights leader Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated, triggering another round of urban unrest. In early November, Republican Richard Nixon was elected president on a platform of “law and order.” Once in office, however, Nixon largely continued and even expanded Johnson’s domestic programs, including Model Cities.

The implementation of Model Cities throughout 1968 was as conflict-ridden as the political fights at national and international levels. The conflicts emerged among different constituencies around various issues. On the one hand, conflict erupted between different ethnic groups fighting over who would dominate decision making and the receipt of resources at the neighborhood level. On the other, conflict erupted between Model City Neighborhoods and the central city administration, which each held a different understanding of what “widespread citizen participation” meant. While citizens often dreamed of total “control” over funding and implementation, the mayor and his associates assumed “partnership,” in which goals would be articulated by residents, but programs would be administered by existing city agencies. Finally, city agencies were unwilling to adjust existing protocols, and labor unions were unwilling to change their admissions standards for civil service, which strongly limited the possible employment of residents of Model Cities Neighborhoods in the funded programs. Conflict at the neighborhood level was most stark in the Harlem-East Harlem Model Cities Neighborhood, where the stand-offs played out between African Americans, who lived primarily to the west of Fifth Avenue, and Puerto Ricans, who dominated to the east. Each group distrusted the intentions of the other, meaning that program meetings often had to be held twice since participants refused to come together in a single space.14

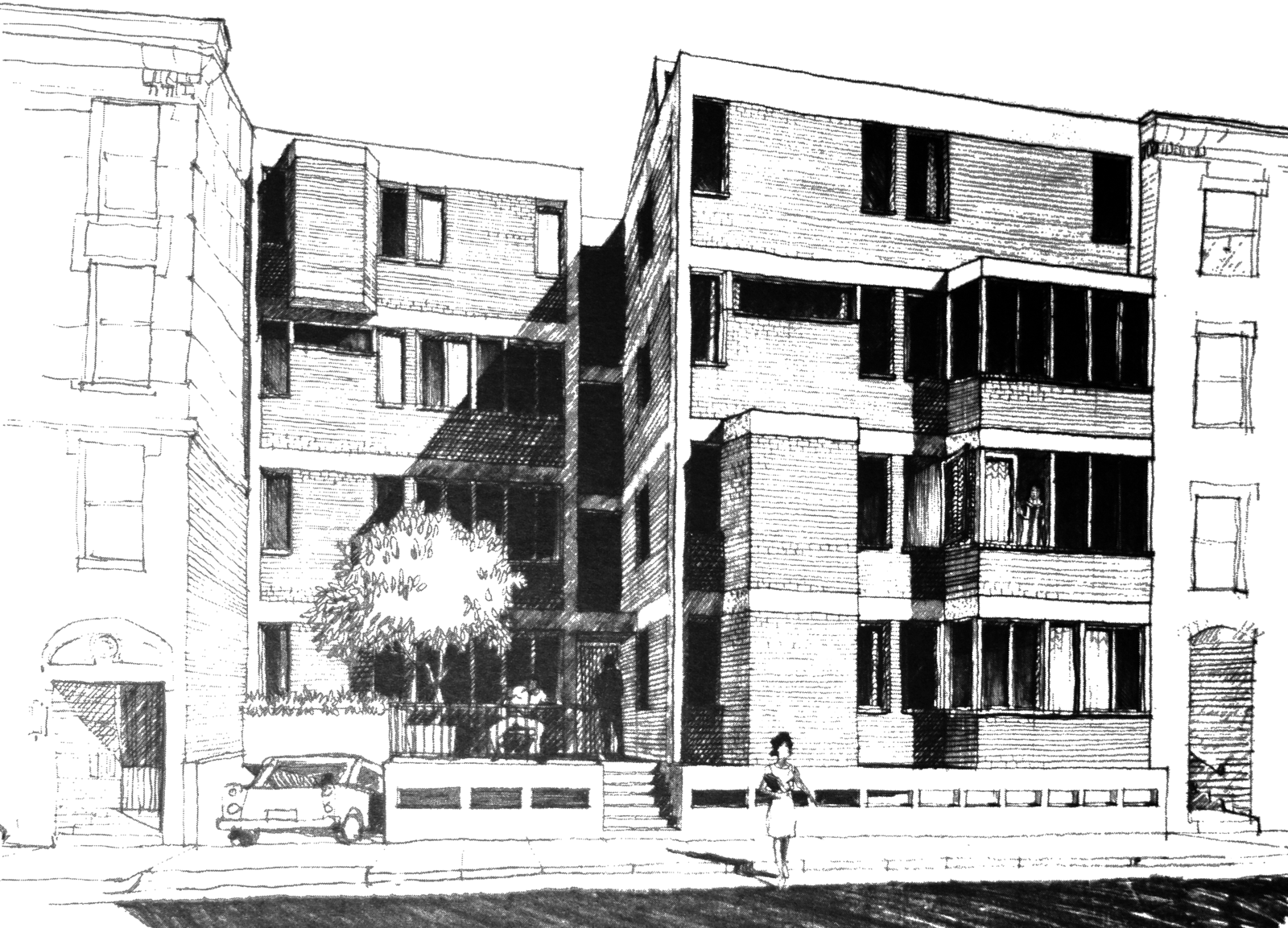

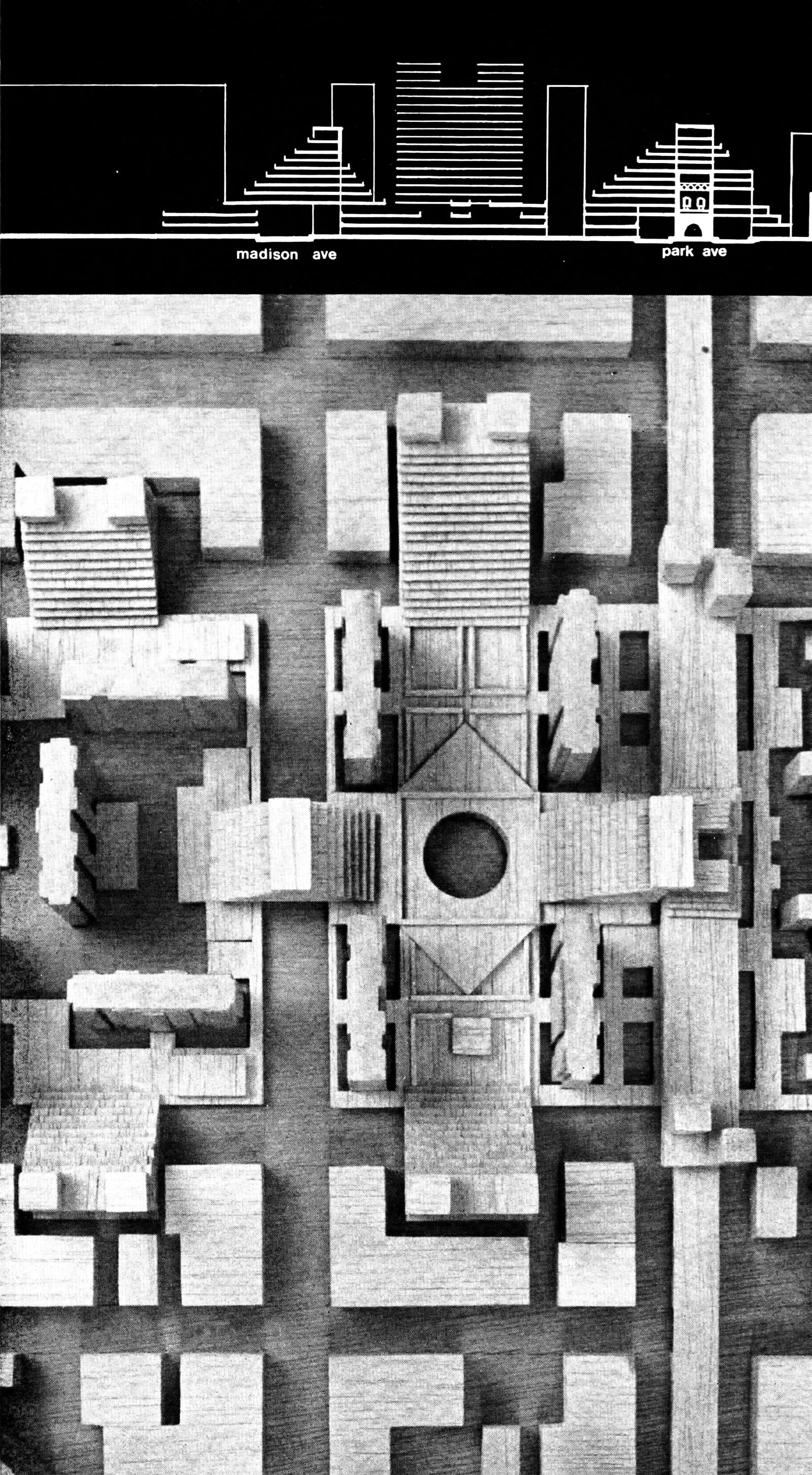

These competing interests were articulated in part through architecture. Barry Jackson, a young Harlem-born, Berkeley-educated architect who was then teaching at Columbia’s School of Architecture and the only African American to be retained by the city in its efforts, was the planning consultant for the Harlem-East Harlem area. Jackson worked with a local committee to site the new rental housing on vacant land, envisioned as three- to four-story buildings built up to the edge of a city block—an incremental approach very much in the vein of Jane Jacobs’s thoughts taking hold at this time. A group of Puerto Rican residents of the Model Cities Neighborhood, however, felt unrepresented in this planning effort and set up their own committee. They engaged Moroccan-born and MIT-educated architect Roger Katan, then teaching at Pratt Institute, to come up with a counterproposal. Titled “Pueblos for el Barrio,” it envisioned large, pyramidal structures bridging streets for residential and commercial use, to be owned and operated by resident cooperatives. The design effort was made possible financially by the J. M. Kaplan Fund, a small, family-run foundation active in urban development issues at this the time.15

Site plan for vest-pocket housing in Harlem’s Milbank-Frawley Circle, developed by Barry Jackson and local residents, from Ellen Perry Berkeley, “Vox Populi: Many Voices from A Single Community,” Architectural Forum, May 1968.

Rendering of Barry Jackson’s proposal for mid-rise infill vest-pocket housing in Harlem’s Milbank-Frawley Circle, from The City of New York, Housing and Development Administration, People and Plans: Vest Pocket Housing, June 1967.

Site section and aerial model view of Roger Katan’s counter-proposal, a concrete megastructure bridging a public housing development and adjacent city blocks, from Ellen Perry Berkeley, “Vox Populi: Many Voices from A Single Community,” Architectural Forum, May 1968.

Site plan for vest-pocket housing in Harlem’s Milbank-Frawley Circle, developed by Barry Jackson and local residents, from Ellen Perry Berkeley, “Vox Populi: Many Voices from A Single Community,” Architectural Forum, May 1968.

More important than the seeming difference in design and development models, the process of discussing architecture and housing prompted concern among local residents and their committees about the role of housing in relation to, and in competition with, the larger, comprehensive goals of Model Cities. One participant in the planning process described the evolution in the community’s thinking as follows: “We were preoccupied with sites, to begin with, but now these are not our greatest interest, although they are the city’s. We want job training and employment first, also social agencies that are community-based and community-operated. We will now be asking people if they want housing at the expense of other things.”16 Through the tangibility of two alternate schemes, local residents had come to understand that perhaps it wasn’t new housing that they needed, but rather reliable sources of income, better schools, and above all, control over these operations, and that given limited funding, they should prioritize the latter. But while these debates might have been conceptually fruitful, they also meant that by February 1968, as the New York Times put it, “the struggle between Negroes and Puerto Ricans had virtually halted all planning for urban renewal and Model Cities projects [in Harlem].”17

In addition to the conflict between different constituencies at the local level, Model Cities also prompted conflict between the neighborhoods and city hall. The Local Policy Committees, set up in 1968, were designing the program goals and plans under the assumption that they were in “control.” City hall, in contrast, understood the process as one of “partnership” between the communities and the city. In May 1969, for instance, the New York City Board of Estimate, the ultimate arbiter over the city’s land use and budget decisions, rejected the plans developed by citizen committees in the Harlem-East Harlem and the South Bronx. The City did not want local, independently acting community corporations to maintain control over funding and implementation, but rather for municipal agencies to carry out local committees’ plans. Despite the objection of many observers and participants, who argued that this would fundamentally violate any trust in the program, and that more time should be given to work out compromises acceptable to all, the City amended the plans according to their ideas. The City then argued, due to time constraints, that if they did not submit their plans to HUD, the federal appropriation of $36 million (of the overall of $65 million) earmarked for the South Bronx and Harlem-East Harlem would expire.18

Overriding the local proposals and refusing to grant an extension to negotiate common ground was the first step toward the city asserting central control of Model Cities. On July 1, 1969, New York City received the first of what would be three annual grants of $65 million dollars. New York was one of over one hundred cities across the county to receive Model Cities funding at the time. But conflict continued. In August 1969, a young man was killed outside the South Bronx Model Cities office after a contentious quarrel between different community groups over the allocation of program funding.19 This news confirmed what was already a widespread perception of the program as being overly complicated and not delivering on its promises.

There was another issue pressing on Model Cities, unrelated to local quarrels. By late 1969, only $7 of the $28 million allocated to the Central Brooklyn Model Cities Neighborhood had been spent, and there was only a single program in operation out of several dozen that had been approved. New York Times reporter David K. Shipler squarely laid blame not on ethnic conflicts, but on the “ponderous city bureaucracy.”20 To illustrate the problem, he examined a block on Prospect Place in Brownsville, where the city had acquired all sites designated by the vest pocket housing committee and demolished all the buildings on it, but nothing was being built to replace them. By late 1969, Model Cities—three years after launching the vest pocket housing program and two years after receiving the first planning grant—had become a political liability for the mayor, especially since he was seeking reelection that fall.

3. 1970–71: Centralization and a Physical Focus

Once reelected, in early 1970 Lindsay restructured and centralized the program. A few months later, Gordon Hyatt delivered his completed film. After long stretches of showing how a program that was originally conceived to counteract conflict had created it, the final scenes of Hyatt’s film finally convey a sense of optimism. We see nurses in white uniforms taking notes in front of a backboard, police recruits training on a gymnasium floor, future sanitation workers learning the operation of a truck, workers laying brick for a new housing development. Here, Hyatt captured the original promise of comprehensive change—a program that targeted social, economic, and physical needs all at once.

But by the time Hyatt delivered his film, the program had already been set on a course that tipped its initial bias for the physical even more strongly in that direction. Despite the reorganization and the direct appointment of neighborhood directors endowed with more powers, Model Cities programs continued to be slow to start, and by January 1971, it was clear that the problems were systemic. The Times’ Shipler wrote a second two-page feature on the program and the matter of “red tape.”21 This time, the graphic he used to drive his point home was not a photograph of vacant lots, but a flowchart that spanned the entire width of the page to show “The 71 Steps City Takes to Purchase Items Like a Desk or a Truck.” In part due to these bureaucratic delays, by early 1971, New York City had still spent only one-half of the $65 million allocated for the first program year, which had ended in mid-1970. At this point, however, the city did find a way to get the money rolling. In order “to increase spending,” Shipler reported, “the city plans to divert most of the left over $32-million into the construction and physical rehabilitation of housing, day-care centers and the like, rather than using it for the operational programs, such as narcotics treatment and job training, for which it was meant.”22 Prioritizing physical programs was a short-term solution with long-term consequences, undermining Model Cities’ comprehensive approach.

Site plan and street-level visualization of Jonas Vizbaras’s proposal for Betances Houses, from New York City Planning Commission, Plan for New York City, 1969.

Beekman Houses, Beyer Blinder Belle, architects, Coldwell Wingate, developer, 1973. Photo: Susanne Schindler, 2018.

Plaza Borinquen, Ciardullo/Ehmann, architects, South Bronx Community Housing Corporation, developer, 1975. Courtesy John Ciardullo.

Site plan and street-level visualization of Jonas Vizbaras’s proposal for Betances Houses, from New York City Planning Commission, Plan for New York City, 1969.

At the same time, the additional influx of Model Cities money for housing enabled significant experimentation and led to models of design and development not originally envisioned by the vest-pocket housing program. As an example of the program’s original intent, in his 1967 plan for Mott Haven, architect Jonas Vizbaras aimed for a balance of different incomes and housing types, ranging from new townhouses to new mid- and high-rise apartment buildings, as well as rehabilitated tenements within each block. The premise was that the City’s Housing Authority—responsible for building and managing low-income public housing—and newly created nonprofit sponsors—responsible for moderate-income housing—would take the lead in implementing the plans. And indeed, the Housing Authority developed over 900 apartments across five clusters of sites, together known as Betances Houses, for which they engaged seven different architects. Three different nonprofit sponsors took on another 900 apartments on four additional clusters of sites. For various reasons, however, including rising construction costs, shrinking federal funding, and long approval processes, the Housing Authority and the nonprofit sponsors were not able to build the housing within the promised time span, contributing in part to Lindsay’s dilemma of having little to show for Model Cities by late 1969. By 1970, new housing development entities thus began to emerge in an attempt to speed up delivery. In Mott Haven, for instance, these included a national for-profit developer and a newly-created local nonprofit corporation. Model Cities’ financial and political support proved essential to both.

The first project was a large-scale rehabilitation effort. In late 1969, Boston-based developer Coldwell Wingate initiated what would become known as the Beekman Houses. The project would ultimately encompass the rehabilitation of thirty-two tenement buildings on several adjacent blocks, creating over 1,350 new apartments within the old shells. Beekman was made possible by federal mortgage subsidies, but just as importantly, by private investment, incentivized through various new tax measures. Provisions in the 1969 Tax Reform Act permitted individuals to shelter income from taxes by investing in low-income housing; they could additionally deduct losses through accelerated depreciation, a benefit that was available for any real estate venture. Beekman Houses involved many such investors, the best known of which being the Tisch family, co-owners of the entertainment giant Loews.23

The Beekman Houses project was designed by architects Beyer Blinder Belle. The architects connected as many adjacent buildings as possible in order to introduce elevators, and gutted interiors to rebuild with fewer, but more varied and generally larger apartments. In connecting modernization on the interior with traditionalism on the exterior, Beyer Blinder Belle were at the forefront of defining a new approach to historic preservation. By coupling private equity investment with generous direct and indirect public subsidies, the Beekman project cemented what would become and remain to this day the dominant model in low-income housing development: subsidized, private, for-profit development.

A second innovation in housing made possible by Model Cities in Mott Haven took shape through the creation of a nonprofit, local community corporation, a type of entity that is today generally referred to a as a Community Development Corporation (CDC). In late 1971, the South Bronx Community Housing Corporation (SBCHC) was officially incorporated. The idea had originated with US Senator Jacob Javits, who rallied key financial business executives to sit on the corporation’s board and give the new corporation needed credibility at city and federal levels. By 1972, this calculation of coupling local activists with Wall Street players proved successful: the city agency originally designated with coordinating the moderate-income housing in Mott Haven passed all its sites and the annual Model Cities operating budget of $7 million to the new local corporation. For the first time, a community corporation had gained full control of a Model Cities program—precisely what all the fighting between the city and the local committees in Harlem-East Harlem, Central Brooklyn, and the South Bronx in 1968 had been about.

The corporation’s first project was the new construction of forty-four split-level, two-unit row houses, clustered on four sites, designed by architects Ciardullo/Ehmann. Plaza Borinquen, as it would become known, preceded the better-known version of the low-rise, high-density prototype designed by Kenneth Frampton in Brownsville.24 As a building type, Borinquen spearheaded the shift toward the two-unit model that would become the basic formula for low-income homeownership throughout the city in the 1980s. As a development model, the creation of the SBCHC was part of the movement to shift decision making, financial, and management responsibilities from a central authority to small-scale players, or what has been called the “decentralized housing network.”25

As different as the Beekman Houses and Plaza Borinquen were, their development and design approaches resulted from unprecedented experiments made possible by Model Cities, something that critics then and historians since have rarely, if ever, acknowledged. Model Cities sat squarely across the assumed divide of top-down and bottom-up, embracing the need for both broad governmental action and citizen empowerment. The program also extended the idea of “partnership” from one between citizens and government to include private enterprise, as both Beekman Houses and Plaza Borinquen show. Whether this blending of large-scale private capital and community-level planning, as was then tested and has since become a dominant model, was the only possible outcome of this decade of fertile experiments, is another question. Ultimately, these early public-private partnerships prevented neither the for-profit Beekman nor the nonprofit Borinquen from shortcomings in management, financial troubles, and even default. In both cases, as early as the 1980s, affordability could only be preserved by new rounds of public subsidies to new owners. In the meantime, public housing, owned and operated by a governmental agency, was never able to recover from the reorganization of federal housing policy in the mid-1970s. In Mott Haven, this has meant that Betances Houses, a project as thoughtfully designed as its for-profit and nonprofit siblings, has struggled to maintain even the most basic level of upkeep and services in light of the continued shrinking of direct federal funding. Fifty years after public housing was considered the trailblazer in vest pocket housing effort, the housing authority is now seeking partnerships with private investors.26

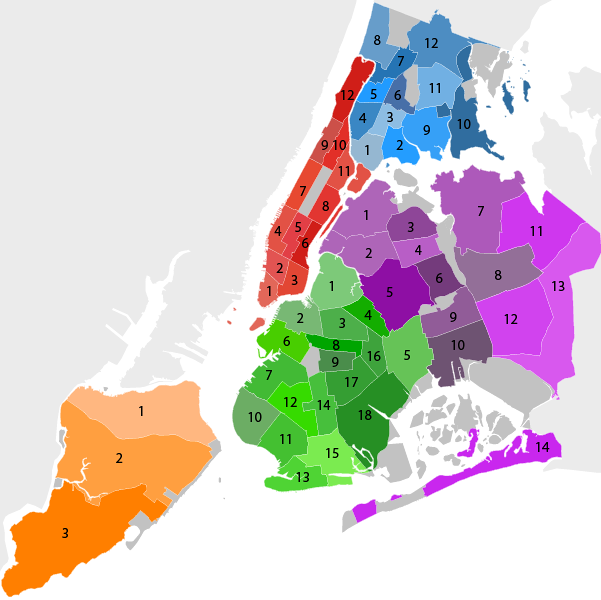

Map of New York City’s Community Boards. Source: Fitnr/Wikimedia Commons.

Legacies: Stabilizing

The shifts in models of design, models of development, and models of democracy that resulted from experiments made possible by the Model Cities program were soon to be codified. With their codification, however, some of their productive aspects—productive precisely because of the conflict caused by fundamental debate around socio-economic inequality—also came to an end. At the level of local democracy, community participation became the norm. Every New York City planning process in 2018 must involve local residents. And yet, since 1975, when the structure and mandate of Community Boards was last revised, their members retain advisory powers only, with no budgetary powers of their own. In other words, Community Boards make no binding decisions, but merely issue comments; the decisions are made at the City Council level. This can be understood as a direct lesson that officials took away from the early and chaotic attempts of Model Cities to implement “widespread citizen participation”: don’t give away too much power. The perpetual invocation of “the community,” while not structurally ceding any real power to it, has led to contradictory situations. In late 2016, for example, fifty out of fifty-nine Community Boards rejected Mayor De Blasio’s proposal for up-zoning low-income neighborhoods. Residents feared, above all, that allowing developers to build more—even if affordable housing were required as part of the new developments—would raise property values overall, leading to their displacement. Nevertheless, the City Council passed the administration’s proposals largely unaltered.

At the level of design, the low- and mid-rise infill approach was also codified by 1975. A zoning program called Housing Quality, which was further revised in 1987 and renamed “contextual zoning,” was coupled with density bonuses and property tax incentives for developers to provide affordable housing. The regulations pertaining to the relationship of contextual design and affordable housing provision was again revised in 2016.27 However, rather than stimulate experiments in hybridizing low- and high-rise design, as was seen with Model Cities, the results have been rather formulaic. Unlike Jackson and Katan fifty years ago, architects and planners today seldom use design to help existing and future residents to understand what different ways of organizing housing might mean. In addition to limiting design options, these zoning and tax incentives have generated little new affordable housing in relation to the expenditure of subsidizing these developments.28

Finally, at the level of development and financial models, ever since the 1974 Housing and Community Development Act, which ended the Model Cities program, Community Development Block Grants (CDBG)—a model which also drew directly from Model Cities’ flexible funding structure—have been the norm for dispersing federal funding for physical development to states and cities. CDBGs can be used for anything from infrastructure improvement and parks to housing. For housing specifically, since 1986, Low Income Housing Tax Credits (LIHTC) have replaced tax shelters for individuals—as used at Beekman—with tax shelters for corporations as the main source of capital for low-income housing. In this model, developers of affordable housing are awarded tax credits in a competitive process, which they then sell to corporations seeking to reduce their tax burden. Both CDBGs and LIHTCs remain on the books today. While this flexibility in funding streams and partnerships with the private sector—as partially experimented with as part of Model Cities—has been durable, it does not make up for the drastic decrease in the direct allocations and value of the tax credits. Between 1975 and 2013, the average CDBG grant shrank from $12.6 to $1.6 million, and the 2017 Tax Reform Bill dramatically reduced the corporate tax rate, making LIHTC much less attractive to investors.

Model Cities was a small, brief, and too-quickly discredited program. It was conceptually on the cutting edge in recognizing that we cannot build our way out of socio-economic inequality, but instead need coordinated and comprehensive approaches to solving structural problems. The program provoked conflict and confusion through its unclear mandate for “widespread citizen participation,” and yet its very openness is what led to productive debate and the development of experimental approaches. This openness was quickly curtailed and restructured into more conventional power hierarchies, and in the process of centralizing, the program’s comprehensive aspect was sacrificed for the politically expedient delivery of housing. Model Cities thus leaves us with a cautionary tale: we cannot promote socio-economic change through housing alone, as tempting as it may be to succumb to the clarity of residential unit counts. Rather, we need to embrace what Model Cities celebrated as a “comprehensive” approach, with its inevitable messiness and harder-to-measure outcomes. With reference to the program’s early renaming from Demonstration Cities to Model Cities, as architects and planners, as residents and policy makers, we need to re-embrace the open-endedness of “demonstrations” over the fixity of “models,” whether political, financial, or typological.

For a recent article on the prevalence of this reasoning both among affordable housing advocates and real estate developers, see Benjamin Schneider, “The American Housing Crisis Might be our Next Big Political Issue,” CityLab, May 16, 2018, ➝.

For a more in depth exploration of the relationship of housing, inequality, and the particular role of architecture, see The Art of Inequality: Architecture, Housing, and Real Estate—A Provisional Report, eds. Reinhold Martin, Jacob Moore, and Susanne Schindler (New York: The Temple Hoyne Buell Center for the Study of American Architecture, Columbia University, 2015), ➝.

“Affordable housing” in its current usage designates price- and income-restricted housing developed by private sector non- or for-profit developers, but overseen by city agencies.

This has changed since the appointment of a new Schools Chancellor, Richard Carranza, in April 2018.

In the mid-1960s, the term “ghetto” was being used interchangeably with “slum,” even though their origins were distinct, the former designating spatial restrictions based on ethnic background, the second designating areas considered physically and morally decaying.

“Turned around” was a phrase used by a task force study leading up to Model Cities; it was defined as an area made interesting for private investment. Report on the Task Force for Metropolitan and Urban Problems, November 30, 1964, 17.

The two key analyses published post-1974 are Bernard J. Frieden and Marshall Kaplan, The Politics of Neglect: Urban Aid from Model Cities to Revenue Sharing (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press 1975); and Charles M. Haar, Between the Idea and the Reality: A Study in the Origin, Fate, and Legacy of the Model Cities Program (Boston: Little, Brown 1975). A study focused on a planner’s experience in East New York is Walter Thabit, How East New York Became a Ghetto (New York: New York University Press, 2003). The sparse recent scholarship on Model Cities, too, largely engages a narrative based on the shortcomings with respect to the declared goal of citizen participation. Key works are Mandy Isaacs Jackson, Model City Blues: Urban Space and Organized Resistance in New Haven (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2008); and Maki Brian Smith, Fighting Poverty Together: The War on Poverty and the Fault Lines of Participatory Democracy, PhD Dissertation, University of California, San Diego, 2015.

I stumbled upon this contract as the last line item of a payments spreadsheet dated October 1968 located in the personal papers Model Cities’ first executive secretary in New York City, Eugenia Flatow. This was a chance encounter in a non-official archive; I had not found a mention of this film anywhere else.

For an excellent study of how CAP played out in Newark, see Mark Krasovic, The Newark Frontier: Community Action in the Great Society (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2016).

Victor Marrero, foreword to Bronx Plan 1968–72: A Report on the Bronx Model Cities Neighborhood, May 1972.

Quotes from City of New York, Housing and Development Administration, People & Plans, July 1967.

For more on the five studies, see Susanne Schindler, “1966 Can Be The Year of Rebirth for American Cities,” San Rocco 14, April 2018: 100–109.

The early difficulties in trying to work with the different constituencies is vividly described by Barry Jackson, the planning consultant engaged by the City, in: “The Legacy of the Harlem Model Cities Program,” in The Urban Experience: A People-Environment Perspective, eds. S. J. Neary, M. S. Symes, and F. E. Brown, Proceedings of the 13th Conference of the International Association for People-Environment Studies (Manchester: Taylor & Francis, 1994): 223-238.

The J. M. Kaplan Fund supported a variety of planning experiments at this time, including the prevention from demolition of Carnegie Hall in 1960, the vest-pocket housing study at Twin Parks in 1966, and the construction of the first legal live-work loft conversation, Westbeth, in the West Village in 1967. The foundation remains active today, but a full history of its activities remains to be written.

Ellen Perry Berkeley, “Vox Populi: Many Voices from A Single Community,” Architectural Forum, May 1968: 58-63, quote from 60.

Steven V. Roberts, “Negro-Latin Feud is Hurting Harlem,” New York Times, February 25, 1968. In fact, neither Jackson’s nor Katan’s schemes were realized, even though the site selection of Jackson’s plan was approved in November 1968. David K. Shipler, “Harlem Housing Approved by City,” New York Times, November 22, 1968.

David K. Shipler, “Board Votes Plan for Model Cities,” New York Times, May 23, 1969.

David K. Shipler, “Aide Dies in Fight on Poverty Funds,” New York Times, August 8, 1969.

David K. Shipler, “Model Cities’ Lag Irks 3 Slums Here,” New York Times, December 20, 1969.

David K. Shipler, “$65 Million in U.S. Slum Aid Snarled in City Red Tape,” New York Times, January 11, 1971.

David K. Shipler, “Lindsay defends Model Cities Aid,” New York Times, January 12, 1971.

Much of the detail on the early investment structure is provided in Kim Nauer, “Anatomy of a Sweetheart Deal,” City Limits, November 1, 1997.

For two discussions of the project, see Karen Kubey, “Low-Rise High-Density Housing: A Contemporary View of Marcus Garvey Park Village,” Urban Omnibus, July 18, 2012, ➝; and Kim Förster, “The Housing Prototype of the Institute of Architecture and Urban Studies: Negotiating Housing and the Social Responsibility of Architecture within Cultural Production,” Candide No. 5 (March 2012): 57–92. ➝.

The concept of the “decentralized housing network” was coined by David J. Erickson, The Housing Policy Revolution: Networks and Neighborhoods (Washington, DC: The Urban Institute Press, 2009).

Betances Houses was transferred to private owners in January 2018. See NYCHA press release, January 18, 2018, ➝.

For the most recent program description of how Inclusionary Housing relates to Contextual Zoning, see New York City, Department of City Planning, “Inclusionary Housing,” ➝.

Critics have focused in particular on the high cost of the 421a property tax abatement, often granted in conjunction with Contextual Zoning and Inclusionary Housing requirements. 421a was first put in place in 1971 and last revised in 2017. For a succinct overview of the limits of that most recent revision, see Charles Bagli, “Affordable Housing Program Gives City Tax Break to Developers,” New York Times, April 10. 2017. ➝.

Structural Instability is a collaboration between e-flux Architecture and PennDesign.