I once designed the exhibition for the collection of an important museum. The brief was simple: we were asked to work with the relationships between artworks in the collection. The museum itself, our client, was open to exploring new narrative strategies and encouraged the exploration of unexpected encounters and syntheses. With the support of art historians and curators, we created an extended list of objects that included the name of the author(s), the date ascribed to the object’s creation, its dimensions, its media, its participation in certain art movements, its current location, and keywords that helped to materialize its own specific context.

While this object list was being developed, we started building a computing script that could generate spatial configurations according to different parameters that were called from this list. The existing architecture of the rooms functioned as the boundary, and configurations and groupings appeared depending on the physical needs of each object and the rules that were set. Objects could be rearranged, for instance, according to the strength or weakness of chronology, movements, or artists.

I should have predicted that the presentation of this tool to the curators in charge would not go well. It is easy, perhaps, to read this exercise as a flattening of art history, reducing it to a dataset (or worse, an existential threat to curatorial and exhibition design practices). The exercise effectively proposed an object list as an exhibition, and algorithms as analytic tools that can be used in the process of curating to activate and deepen relations, groupings, and placements. Our proposal ultimately wasn’t implemented, but these ideas have haunted me since.

The object list is an essential tool in the creation of an exhibition. It speaks to a series of processes within the hosting institution or organization, from funding applications to the paperwork necessary for the loan of objects. In most cases, it is the object list that triggers institutional censorship. Institutional eyes comb through the object list trying to find anything at fault, to identify the possibility of trouble, the triggering shot, the overflowed watermark of public offence. But sometimes it is the object list that occludes the censoring eyes.1

The object list crystallizes all the different processes required to create and produce an exhibition; it threads the sinuous path of collaboration from conceptualization to spatial design. When there is little collaboration between curator and architect, the object list becomes the only point when both intersect and therefore it represents the smallest common denominator between both. As a result, it often becomes the key territory of negotiation. “We need more wall surface; we cannot have too many vitrines; there is only enough space for three plinths, etc.” While the architect wants to have a clear idea of the elements in the exhibition in order to plan and draw, the curator often expands or changes the object list as response to the architect’s ideas. In collaboration, the object list is always malleable.

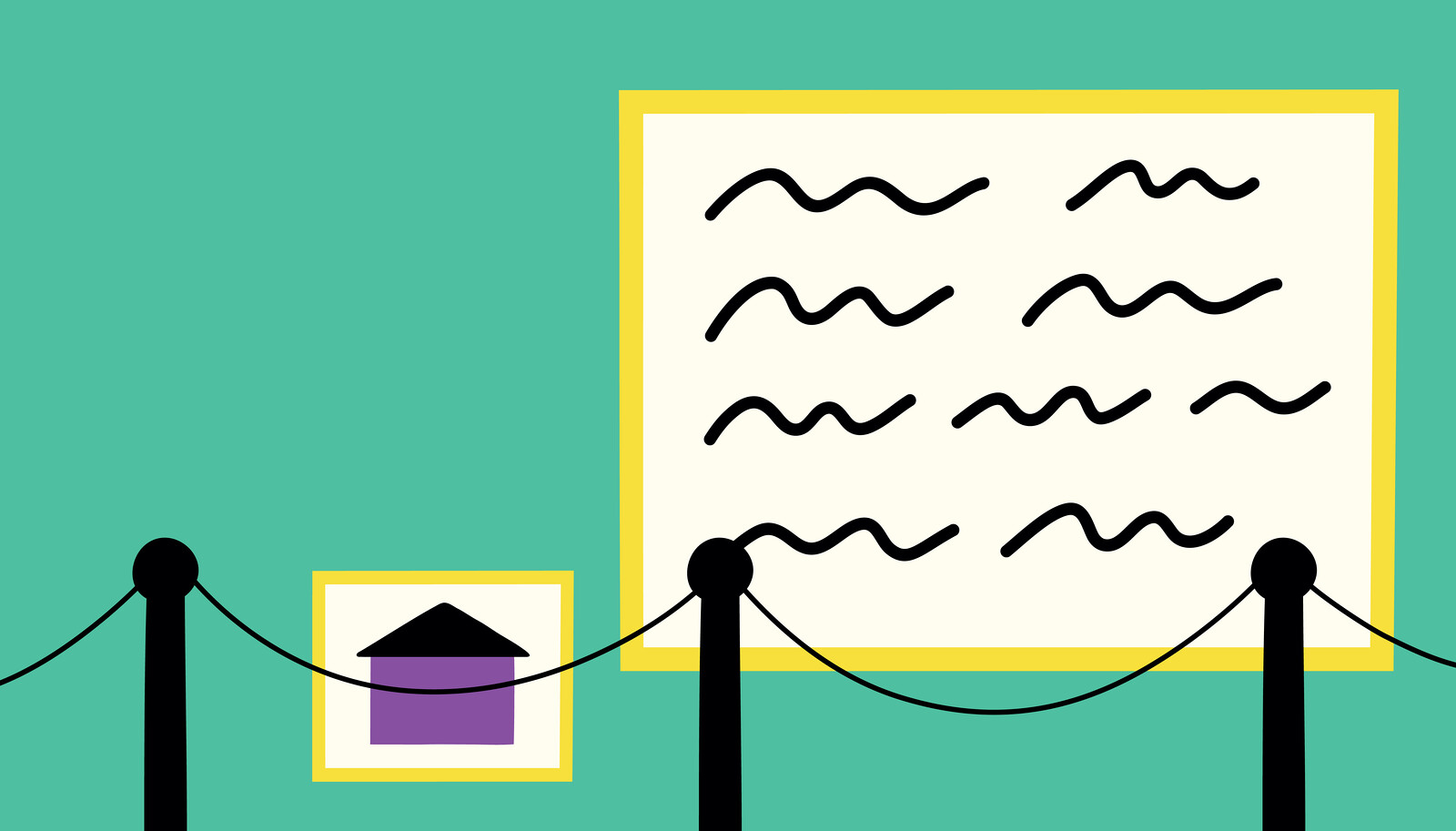

When finalized, the object list manifests the exhibition as a complete and singular body. Object lists are defined, fixed, organized sets of data. Their beauty lies in their almost total detachment from hierarchy; each object it describes is taken on face value, all part of the same list. But sometimes the object list gets contaminated by elements that are part of the architecture, or the display becomes so embedded with the exhibition that they start existing together as one. “Should that specially-designed vitrine be part of the object list? Is that reproduction of an artwork an “object,” or is it “just” scenography?” The moment an object becomes part of the object list it gets funnelled into a whole set of new institutional rules, like conservation and insurances. In other cases, artists intervene directly in the building and the building itself starts appearing in the object list, like Karel Appel’s mural in the former Stedelijk canteen that is now covered behind plasterboard, or Wolfgang Tillmans’s suspended walls at the Serralves Museum in 2016.

The object list can be the most beautiful version of an exhibition catalogue, simply because it is undigested. The hierarchies that become so readily apparent in the booklet or in the catalogue are not yet present or formalized. The thoughtful sizing or color profile of each image, or what the A text, B text, or C text will be, are all absent. The object list, in this sense, is reminiscent of the specimen-driven natural history slideshows of old, pragmatic in their presentation and radically open for interpretation. Perhaps I am nostalgic of the taxonomic approach of the cabinet collections because it feels particularly refreshing in a moment when the thematic exhibition has become the de facto approach. This freshness comes from an openness that lacks the consensus that is necessary when we create stories. Responding to his firing from MACBA in 2015, Paul B. Preciado insisted that “the museum should not build a story, because a story is consensus, is a point of view, and therefore a boundary that generates exclusion. The revolutionary role of the museum is to become a space where dissident representations and languages can be discussed and negotiated.”2

The walls of the classical French salon in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries were covered in paintings by different artists, all intended to be read as singular entities without consideration of their spatial or thematic relationships. But then artists transcended the finite quality of the object. Later, during the twentieth century, the context of artworks became a more central focus, so curators prioritized the relationships between works in order to communicate an overarching idea. The object list is in permanent tension between its inherent openness and the assumptions and consensuses that are needed in order to create context.

What if the object list is not thought as a singular entity, but as an open, active tool? This changing object list would not assume a fixed history or a dominant vision, but instead allow for change, for curiosity, and discovery. What if new museum exhibitions would not simply begin when another finishes, but would rather morph from one to the other, crystallizing in places and blending into a continuous experience of display? Changing the object list into something pliable would also affect funding strategies. In principle, exhibitions could be cheaper—partly down to the fact that fewer objects would be necessary in each iteration, but also consistent change would require more consistent, long-term funding. A new set of standards would be necessary for the evaluation of what constitutes a “success” or a “failure,” deviating from visitor metrics and ticket sales and encouraging the freedom to embrace both stability and instability alike. The mutant object list would work like a playlist, changing according to programming, to what we have seen, to what is new. The object list would be in constant flow.

Perhaps one positive aspect to the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic is the fact that it has, in a very general sense, reduced our threshold for boredom. I sit anxiously with the knowledge that the upcoming barrage of events, shows, festivals, meetings and so on appears to be looming. And when that time comes, I will not be alone in feeling nostalgic for the comparative stillness of the pandemic experience. With this in mind, perhaps we could think of the exhibition less as a “show” and more as a reading club, taking you on a journey that values your own agency, decision-making processes, and makes room for the inevitable cognitive jumps and hiccups that define “thinking.”

In 2015, Bartomeu Marí, then director at MACBA, decided to cancel the exhibition “The Beast and the Sovereign” one day before the opening after realizing he had signed the loan paperwork to exhibit the sculpture Not Dressed for Conquering by Ines Doujak, which depicted King Juan Carlos being taken from behind by Domitila Chúngara, a Bolivian labor activist. Marí eventually resigned from his post after firing the two curators of the show, Valentín Roma and Paul B. Preciado. The show was finally opened to the public, including the sculpture, and with more than the expected number of visitors.

Peio H. Riaño, “Paul B. Preciado, el comisario más influyente del arte contemporáneo,” El País, November 19, 2018, ➝.

Solicited: Proposals is a project initiated by ArkDes and e-flux Architecture.