Not so many centuries ago places, buildings and cities were their own and only form of visual representation. They stood in one place and could not be transported but in stories and songs through the memories and imagination of people who had experienced them first-hand. A type or style of architecture was bound to the ground they stood on, not only physically but also virtually, and seldom spread beyond its immediate geographic and social boundaries. Then, as now, technological and cultural innovation was reliant on the exchange of knowledge. Without the ability to transport information through reliable and trustworthy media, the evolution of grounded artefacts like buildings evolved slowly and only over short distances.

This limited and fixed state ended 500 years ago as architecture, enabled by print, started to travel virtually through vast distances, only to appear physically again by the hand of people who were just as distant in the first place. The media that buildings initially travelled by was the book—the first mass media object containing flattened visual representations of architecture which could be transported without much physical deterioration or distortion of the information contained therein. The first ideas and representations of architecture to travel virtually through the book came from Renaissance Italy and spread across Europe in books like Sebastiano Serlio’s On the Five Styles of Buildings first printed in Venice in 1537, which described reproducible elements in clear black and white illustrations.

Architecture’s visual representation was dominated by the book and etchings for centuries. Later came photography, cinema, television, and eventually the internet, where increasingly complex and precise information about buildings could be transferred at ever greater speed and distances. This steady progression has in turn led to styles of architecture replacing each other at ever greater speed with many distinct and impactful ones lasting only a decade or two and being identified with more discrete characteristics. Architectural style is formed within media and it is independent from place.

Besides speed and availability, aesthetic fidelity also plays an important role in the transfer and formation of architectural styles through media. The amount of senses involved in communication is fundamental to the effective transfer of any message. Reading a description of a space in text can be informative and stimulating, but seldom further transferable between individuals as the amount of subjective interpretation is higher the further from the source we get. Photography, film, and videogames take us closer to a more comprehensive transfer. Immersive wearable media will, in our lifetime, be able to achieve unprecedented degrees of visual and aural fidelity that combine the qualities of all previous formats, all perceived in three dimensions.

The experience of digital 3D models via wearable immersive media has been termed “virtual reality.” This is, however, no more than another step in the long history of immersive virtual architecture. The millenia-old frescoes of Villa Regina in Boscoreale are as much virtual reality as the acclaimed 2020 return to City 17 in Half-Life: Alyx.1 Not all forms of architectural representation can qualify as a form of virtual reality, however, since not all of them succeed in immersing their viewer within the space they describe or depict. This sense of immersion relies on successfully establishing enough connections to memories that compose a multisensory experience. This is why a text-based description can be more successful in “bringing us there” than a 3D environment experienced through VR goggles, if the references used in the descriptions of space are accurate and relatable. Virtual architectural experiences are therefore not necessarily synonymous with digital technology, and have existed well before the headset.

***

Every technological innovation has given origin to a cultural shockwave that ripples through and reshapes our visual culture from within. Consequently, this leads to new styles and forms of behaviour and socio-politics, as our ways of living are shaped by the way we represent and transfer information. Our buildings and artifacts therefore represent us and our time as much as we represent and embody them.

Architectural style is no different than jewelry, sculpture, or graphics in this regard. But it arguably works at a different pace: architecture communicates between generations, not individuals or communities. The style of a building is a collective effort to petrify sets of values and hopes for the future. In this sense, style in architecture is a form of time travel, not a real-time conversation.

The incredible speed of development of media infrastructure in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries led not only to the spread of architectural styles, but also to variation in the ways in which space is thought about, created, and used. It also led to a considerable degree of confusion and overwhelm about how to make sense and use of the newly available style galore.2

Just as a large vocabulary increases one’s ability to precisely express themself, a wide range of styles in use and circulation increases architecture’s ability and precision in communicating ideas. Today the Pinterest Board enables people without previous knowledge of architectural history to put together images of buildings and interiors and appreciate similarities or recognise patterns that are, in other words, unnamed styles. Sharing these collections of images, we communicate complex and nuanced ideas about space and style that we do not have words or names for. This language is enabled by the sheer quantity and immediate availability of images.

As immersive media continues to evolve, individuals might eventually be able to communicate to one another through architecture in ways not too different than we do through images today. If the meme or the emoji are the result of the greatest archive of images becoming readily available and exchangeable through the internet, what happens when virtual spaces and digital environments become created, circulated, and consumed like images? Can the immediacy of architectural space through immersive media and real time rendering lead to a conversational language?

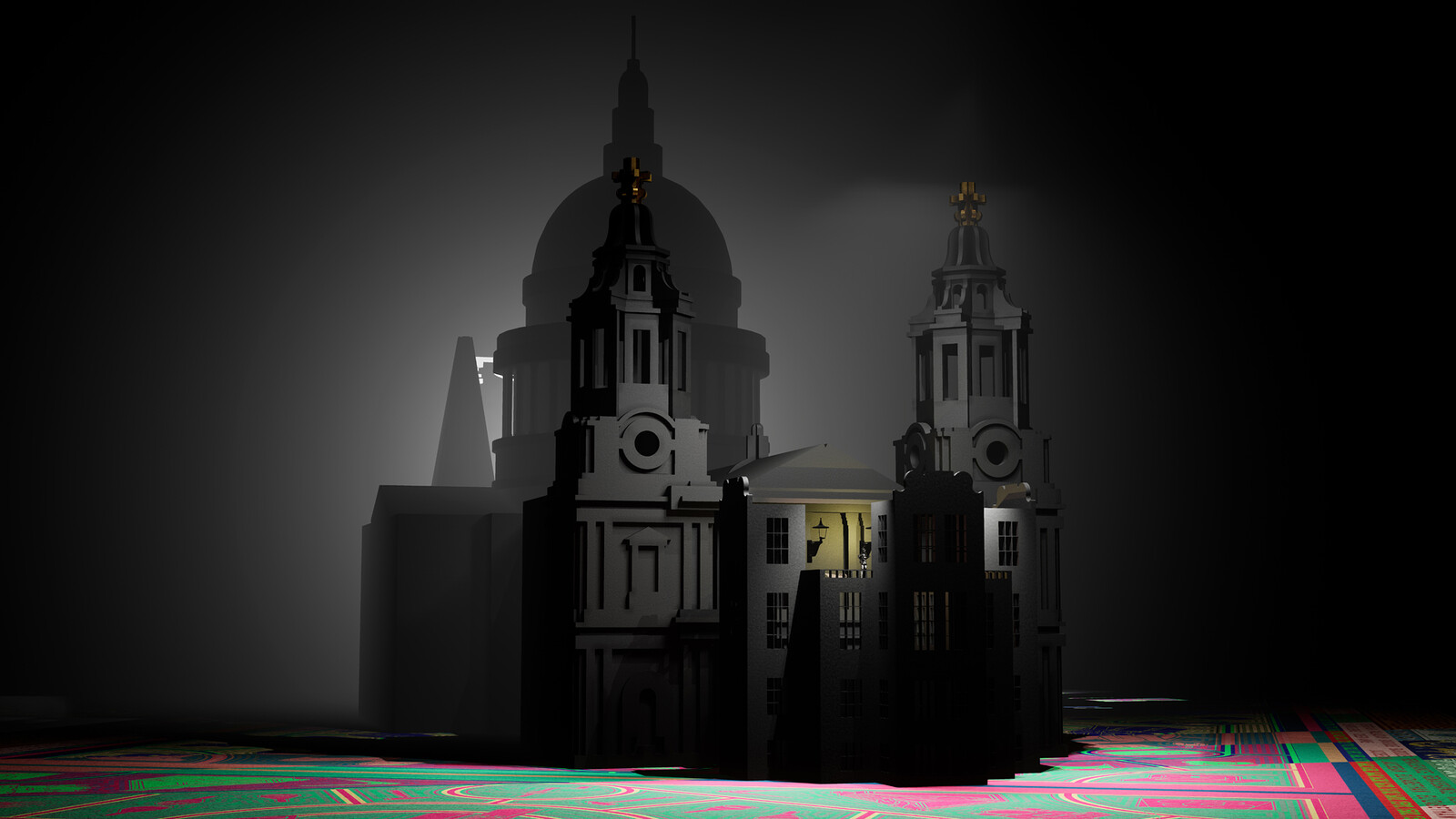

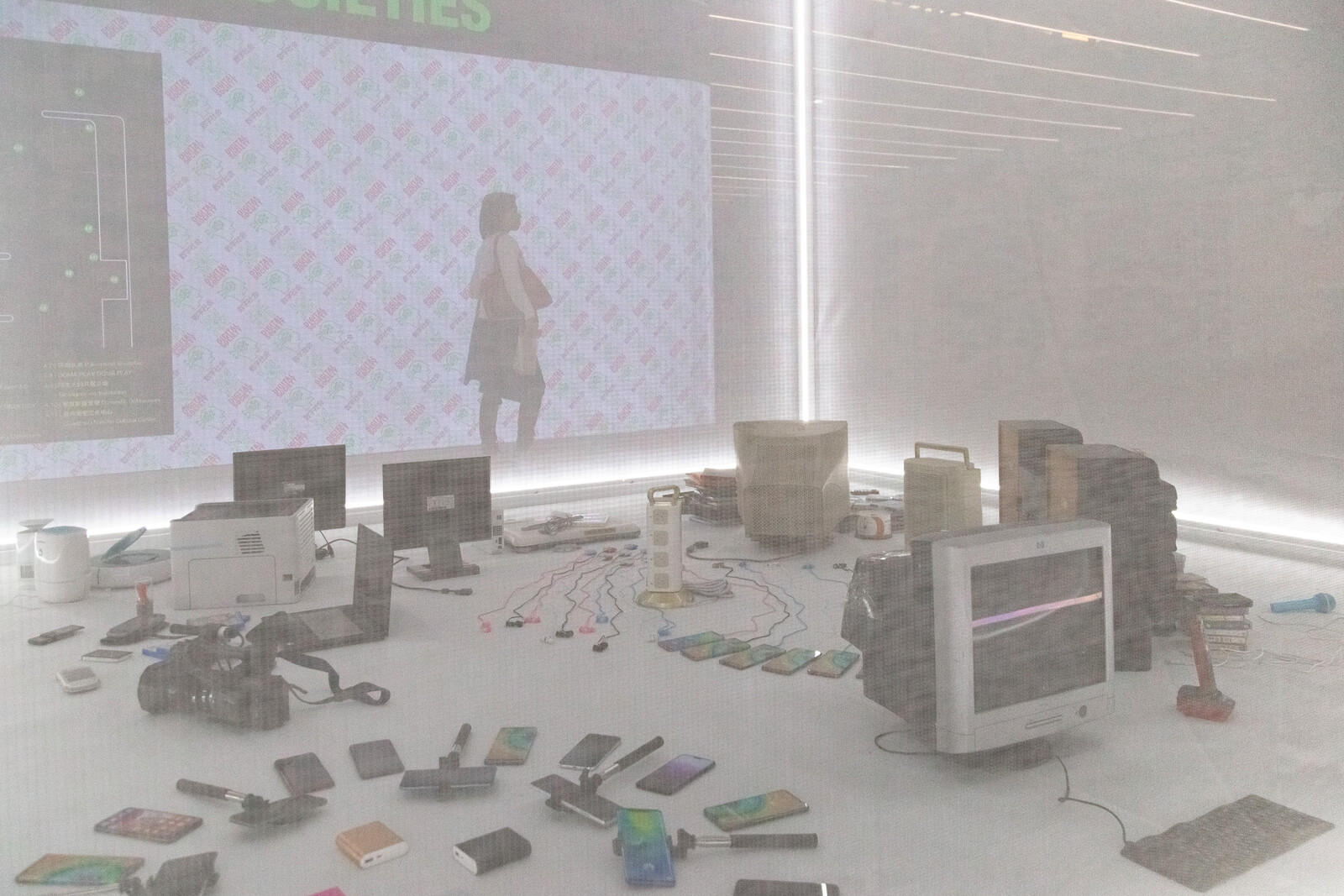

Space Popular, FREESTYLE: Architectural Adventures in Mass Media, curated by Shumi Bose, Royal Institute of British Architects, London, 2020. Photo: Francis Ware

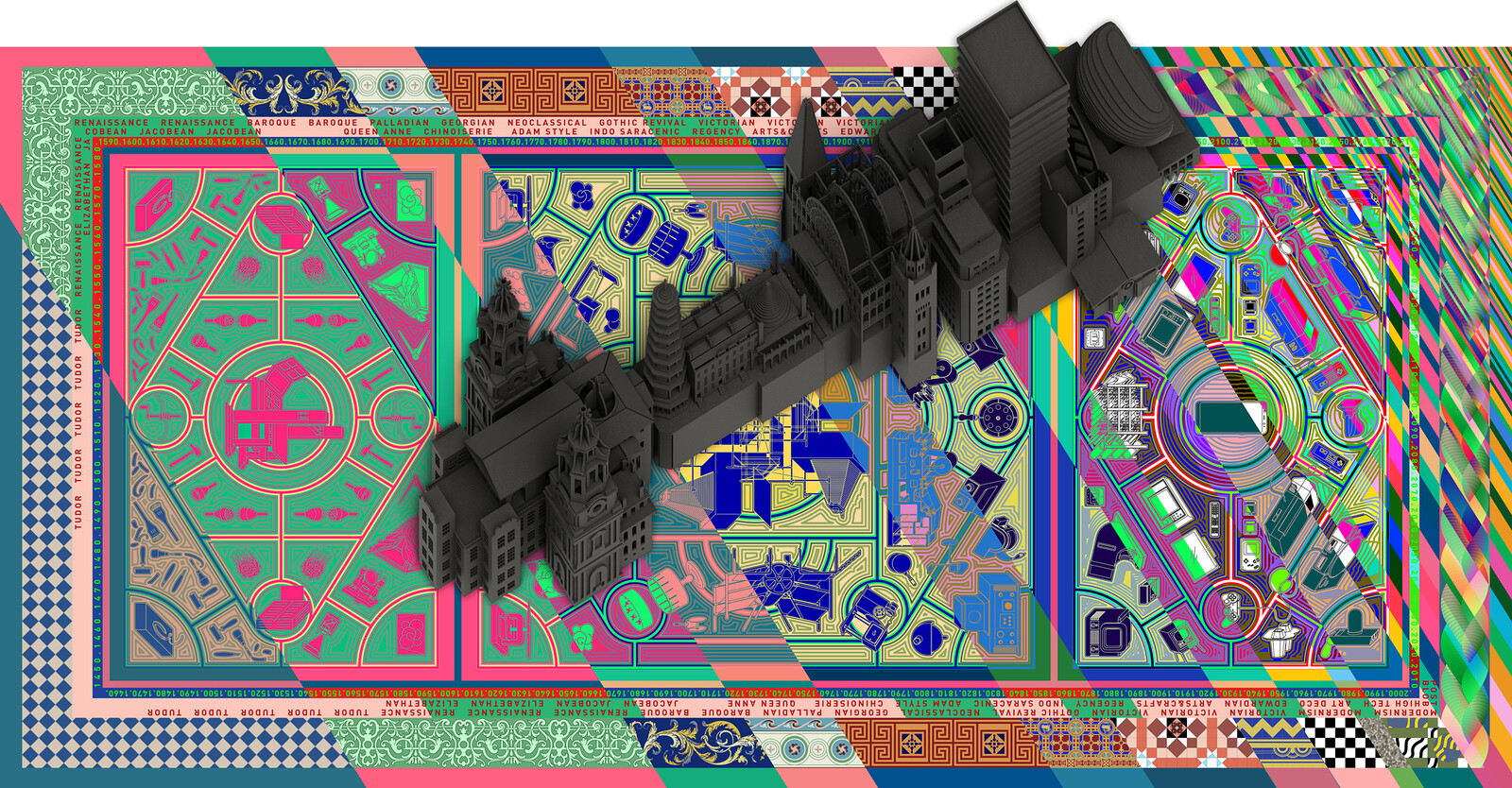

The narrative that follows was originally set within a mixed reality experience and organized according to a timeline. Varying color schemes and ornaments mark the boundaries between prominent stylistic periods in Britain, while figurative motifs illustrate the machines that facilitated access to different forms of media across centuries. Moving along the timeline, one can see iconic versions of the different architectural styles represented on the 1:30 physical model and simultaneously read the gradual increase of density of styles on the carpet.3

Mass media such as the book, television, and the internet have influenced the style in which we design and construct buildings. This story takes place in Britain, but addresses faraway buildings that, through mass media, were brought closer and, like this text, able to travel far beyond the land where they originally stood.

500 years ago, buildings could not travel, so people had to.4 If you wanted to get inspired and learn from the visual form of a building, you had to go see it in person. This was not something which was possible for most people in fifteenth century England, let alone the chance to design a building.

The design of the visual form of buildings was, and would remain until the twentieth and twenty-first century, an exclusive form of creative expression. Almost six hundred years ago, however, the first true form of mass media—the printing press and, in turn, the book—helped spread ideas about architecture (among many other things) without the limitations established by its heavy and static nature. Buildings could now travel.

Few books had such a great influence on the way buildings look in Britain than those written by the Italian architect Sebastiano Serlio. His was the first book published about architecture containing illustrations and drawings, crucial to learn about and experience buildings remotely.

Serlio wrote about the then-new style of the Renaissance and its five orders, which was in full swing in Italy and much of central Europe at the time. He also wrote in Italian rather than Latin, and in a way which was purposely easy to understand. He wanted his readers to understand, appreciate, and subsequently, imitate. It was the beginning of what was to be called the “pattern book.”

During the late sixteenth century and in the wake of the reformation, few churches were being built in England. Wealthy families, however, were building large country homes, many of which featured styles influenced by these kinds of pattern books from the continent.

Robert Smythson, a mason and one of the first architects in England, built many of these stately homes. His work was heavily inspired by illustrated books by renaissance revolutionaries such as Hans Vredeman de Vries, Andrea Palladio, and of course Serlio. Smythson is not known to have ever left England to see the new style shown on the pages of those books in person.

Built impressions of the new style would however not be seen until the early half of the next century, created by the well-travelled Inigo Jones.

When people like something, they tend to want more of it. As the new style introduced by Serlio’s and Palladio’s books became increasingly popular, it also got larger, flashier, and more extravagant.

The “more is more” architect of the day was Sir Christopher Wren, who would be credited with designing over fifty churches following the near total destruction of London in the Great Fire of 1666 and subsequent building frency. Among them was St Paul’s Cathedral in London.

In order to design this staggering amount of buildings, Wren relied almost entirely on a steady flow of pattern books and etchings from the continent. His tutor Lady Elizabeth Wilbraham—the first known female architect in England—had travelled throughout Europe, but he is reported to have left England only once to visit Paris for a few weeks.

A stream of translated books continued to boost European ideas on design, including easily readable versions of works by Palladio and Leon Battista Alberti. In 1715, Scottish architect Colen Campbell published a book inspired by Italian authors like Serlio and Alberti, as well as a three-volume translation of Vitruvius: the Vitruvius Britannicus. Campbell’s devotion to Palladio is evident at Mereworth Castle in Kent, an almost exact replica of his Villa Rotonda in the Veneto. This tribute appears just as Blenheim Palace—generally regarded to be the last Baroque building in England—is completed.

Another version of the Villa Rotonda, the Chiswick House, was built by Lord Burlington and William Kent, who simplified the original, stripping most of its ornaments. Maintaining classical proportions and domestic scale, this refined simplicity became the signature of English Palladian style, visible in countless houses and town halls. These proportions and their pleasing flatness would eventually characterize the later Georgian era.

The fashion for rich ornament coincided with fanciful revisions of the past, as the middle-class architect began to wander in time as well as space. For example, the romantic “Gothick” style, recalled medieval Northern Europe.

As a result of colonial exploration, tastes developed for exotic features from the Far East; decorative new styles were named to suggest their origins, such as Chinoiserie and the Hindoo Gothick. As travel and trade with the Orient increased, pattern books appeared in a wide array of styles and tastes. Prolific architect-authors like William Halfpenny and Batty Langley published architectural catalogues for builders and carpenters, who would reproduce specific parts of the architecture, rather than entire buildings.

Employed by the Swedish East India Company, Swedish-Scottish architect William Chambers travelled to China several times. His Pagoda at Kew Gardens and book of Chinese designs signalled a fashion for Oriental follies across the country.

Egypt and the Middle East had their moments too. Napoleon’s Egyptian campaign in the 1790s inspired Owen Jones to make studies of Islamic architecture in Cairo and, later, in Moorish Spain. His survey of the Alhambra developed his theories of pattern, color, and geometry, and informed his encyclopedic masterpiece, The Grammar of Ornament. Its vibrant color images were made using a painstaking process, which required up to twenty stone-cut printing blocks for each plate.

One of the most extreme examples of Orientalism is the Brighton Pavilion, built for the Prince Regent, or George the Fourth. It is one of the last ornamental buildings influenced by catalogues of ornament before the invention of the camera. This fantastical patchwork took its inspiration freely from the architecture of the Hindu temples and Islamic mosques of India.

Meanwhile, the Georgian townhouse devoured whole streets of Britain’s towns and cities. With the help of cheaper pattern books, builders had mastered this urbane brick typology: adaptable, affordable, with an echo of Palladian sophistication and, for developers, as easy to sell as it was to replicate.

The Victorian urge towards global economic, technological, and cultural dominance led to the building of The Crystal Palace, which astonished visitors with its innovation. Joseph Paxton’s unprecedented glass hall design was built in record time, resulting in a light-filled space such as had never been seen before. The use of prefabricated architectural elements marks a historic division between architectural reproduction via the sharing of images and ideas and the industrial reproduction of material parts of a building.

Full of wonders from across the known world, the Great Exhibition—which took place inside the Crystal Palace in 1851—was a grand spectacle, and one of the first to be documented in the new medium of photography.

The end of the nineteenth century saw the invention of the motion picture. The glorious 1920s had people dreaming of American movie stars in glamorous Art Deco interiors. Projected in monochrome, the lenticular silver screen exaggerated the effects of strong shadows, contrasts, and refined formal features captured on camera.

Not only depicted in cinema itself, Art Deco was frequently chosen as the style for the buildings where films were played and made. A recognizable feature of Odeon cinemas, Art Deco also featured in other media-production buildings such as BBC Broadcasting House.

Just before the sophistication of Art Deco took off, another substantial species emerged: the Victorian urban block. Large-scale metropolitan buildings were built in the spirit of the pattern book, replicating units and volumes as vast factories or workhouses and mixing sparse decorative elements of various derivative styles.

But the accelerated rate of change in the twentieth century called for a novel type of ornament: trading the spin-cycle of historic conventions for new materials and new types of building. Mechanical efficiency provided inspiration to sweep away the cobwebs and constraints of tradition. Streamlined shiny vehicles, mass produced domestic objects, even flying machines made up the airbrushed dreams of progress. New styles of photography enabled by compact cameras would show these buildings at oblique angles portraying that sense of motion.

Increased industrialization, communication, and the abundance of media images made it possible to publish more and cheaper than ever before. This led to an explosion in the number of magazines, gazettes, and periodicals of increasing variety. Print media went from precious to ubiquitous, enabling a new form to enter the toolbox of architectural representation: the collage.

Cropped photographs of real people doing everyday things were clipped from magazines and inserted into architectural drawings, suddenly “animating” the abstract and endlessly repeated environments of high Modernism. Picturing life as it might be lived allowed such spaces to become more relatable. At the same time the category of “lifestyle”—packaging the everyday into a consumable form—is invented.

Queen of appliances, when the television is received into the domestic realm it replaces the hearth or fireplace as the focal point of the “living room.” Now, everyone could have the Great Exhibition in their own home; audiences in their collective millions tuned into international news bulletins, informative broadcasts, musical variety shows, and cell-animated cartoon-scapes, all at the turn of a dial. This new form of entertainment reduced the strain to communicate from architecture, as its perpetual and mesmerizing availability allowed physical space to recede.

Film and television set design becomes a new field for architectural design—as theatre had been in centuries past—with architects like Ken Adam designing the collective imaginary of generations. Now architects were designing the “ideal image” of life, as well as the reality of postwar globalization and urban development.

The portrayal of lifestyles—composed of an array of things such as routines, objects, and interiors—could now reach the general public, as opposed to being reserved to personal acquaintances as it was before. The idea of architecture becoming a part of one’s self-image becomes widespread, and the desire to express oneself holistically through the domestic interior in ever more unique ways grows beyond the exclusive circles in which it used to be contained.

The fractured references of Postmodernism, which celebrated the symbolic power of pop-culture, went hand in hand with an increased focus on the self, delivering an architecture that aimed to communicate directly and legibly, revelling in shared contemporary images and thumbing its nose at elite conventions.

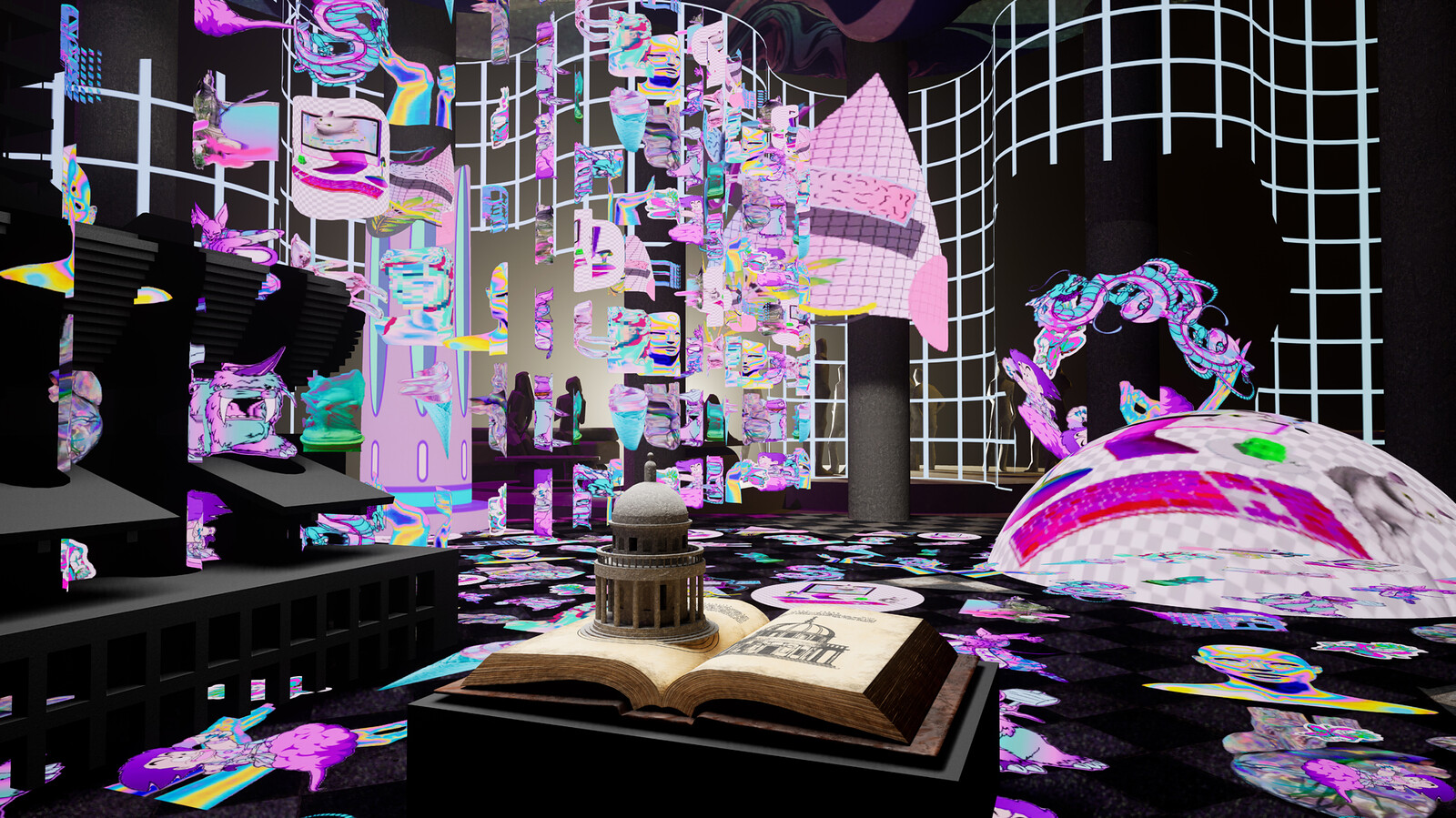

The video-game console opened up an abstract new world: what was once understood as the representation of a physical world became an end in itself: a virtual place to be. Architectural projections became the world of “digital space,” populated with fictional avatars with whom we identify. Architectural styles served the narratives of game scenarios, as we immersed ourselves in 8-bit worlds, while early flirtations with immersive goggles and headsets waited around the corner.

The internet is the largest collection of architectural inspiration that has ever existed. This bonanza of content does not come without its challenges, one of them being sorting. Unsorted data is virtually meaningless. The pattern books used by architects in the past did just that—sorting and classifying examples according to type and style. They made use of our unique and powerful ability to recognize what things are and find connections between them. As we look back in time we can see patterns and therefore recognize styles and read meaning into them. Impossibly slow and somewhat incoherent, the history of architecture could be seen as one huge book with millions of authors. A book without words, but with architectural styles in constant translation. This book of styles is being re-written faster than ever, and the more we compile, the more eloquent and expressive we could become.

As we find ourselves able to step into virtual worlds, we no longer have to remain on the other side of the frame. Now we can step into virtual buildings and walk around them. We have gone from reading media to experiencing it.

Communities are already forming in virtual social spaces, where hundreds of thousands of people from all over the world meet, often taking the form of highly stylized virtual avatars. Though there is no need for shelter in virtual space, nearly all of them have some kind of enclosure, showing how architectural style affects our behavior and is intrinsic to how we structure our social and individual values in physical and virtual space.

It is only natural that this wide access to architectural style would first lead to an abundance of expression. But we can already see a critical response to the smooth, friction-free digital world: there’s a new wave of architecture which privileges texture and—paradoxically—materiality. A “Haptic Revival,” which flows across realities, physical and virtual alike.

In the coming decades, architectural experience as a form of self-expression will become available to many, enriching a language that once belonged to the few. The promise of inclusiveness does not come without potential for abuse, manipulation, and other forms of misuse. It is in our hands to decide how we shape the future of our newly arrived virtual realm and, in turn, our built environment under the premise of a land of FREESTYLE.

Vincent Acovino, “’Half-Life: Alyx’ And The Promise of Virtual Reality,” NPR, April 9, 2020, ➝.

In reference to the nineteenth-century “style wars” started by Heinrich Hübsch in his essay “In What Style Should We Build?,” 1828.

More about the FREESTYLE exhibition curated by Shumi Bose at Royal Institute of British Architects here.

Mario Carpo, Architecture in the Age of Printing (MIT Press, 1998).

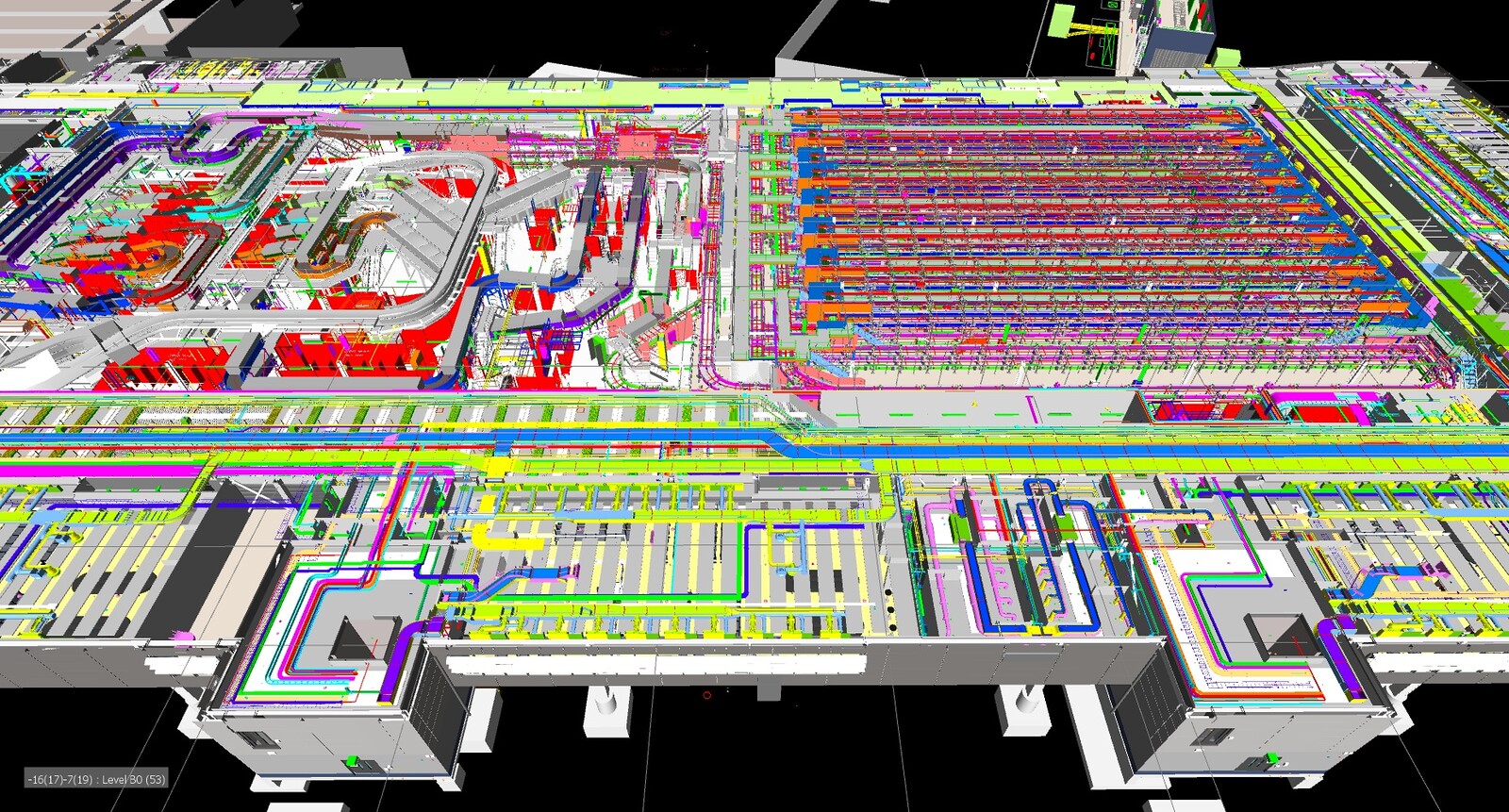

Software as Infrastructure is a project by e-flux Architecture as part of “Eyes of the City” at the 2019 Bi-City Biennale of Urbanism\Architecture (Shenzhen).

Category

Subject

FREESTYLE – Architectural Adventures in Mass Media is a RIBA-commissioned exhibition by Space Popular and opened at the Architecture Gallery at the Royal Institute of British Architects, London, in February 2020.

Software as Infrastructure is a project by e-flux Architecture as part of “Eyes of the City” at the 2019 Bi-City Biennale of Urbanism\Architecture (Shenzhen).