Architects deal in imagined conditions, seeking to imbue their images with a mix of plausibility, desirability, and futurity so irresistible that the conditions depicted will be made real. While technical drawings convince their audience of their power by means of signatures, conventions, accuracy, and abstraction, the architectural visualization (the rendered photomontage) plays off a different register. Rather than giving instructions for how a building will be built or used, the photomontage attempts to move its audience to actively desire the realization of that which it depicts. The visualization is thus one of the key affective interfaces between the products of architectural labor and architecture’s diverse publics.

Despite their central role, it’s perhaps odd that it is so hard to care about architectural visualizations. They are ubiquitous. They all look more or less the same. They all have the same (usually white, generally badly dressed, perpetually awkward) people. They adopt the same angles, the same weather, the same views (birds’ eye or that of the average-height male). Light falls in the same way across their anemic surfaces. They manage to make “urban life” seem vaguely pathetic, even to those of us who, in reality, don’t mind the occasional overpriced coffee and have a deep but unarticulated affinity for alfresco dining. The world of the photomontage is a highly uninteresting world, a place that inspires ambivalence at best.

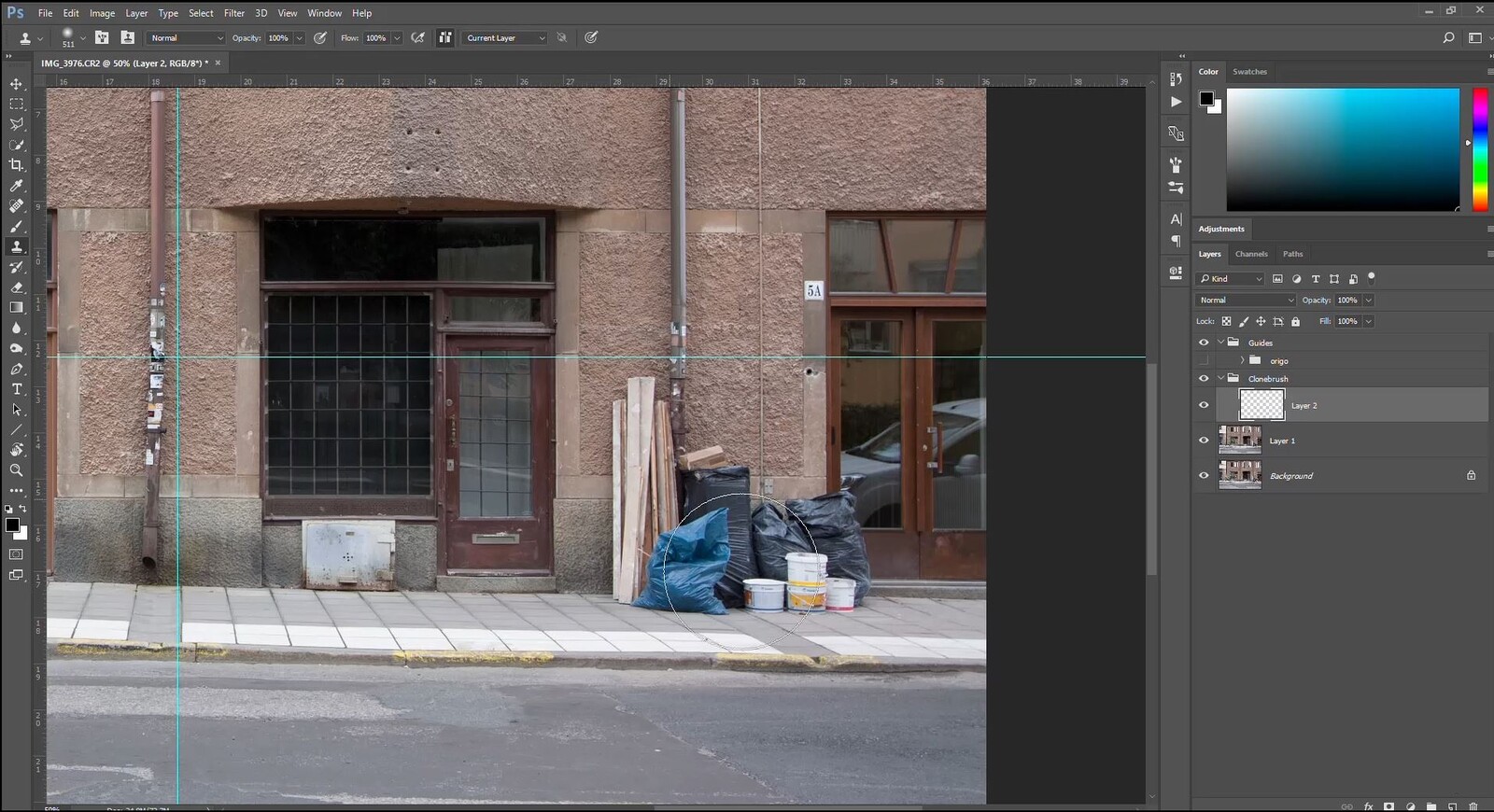

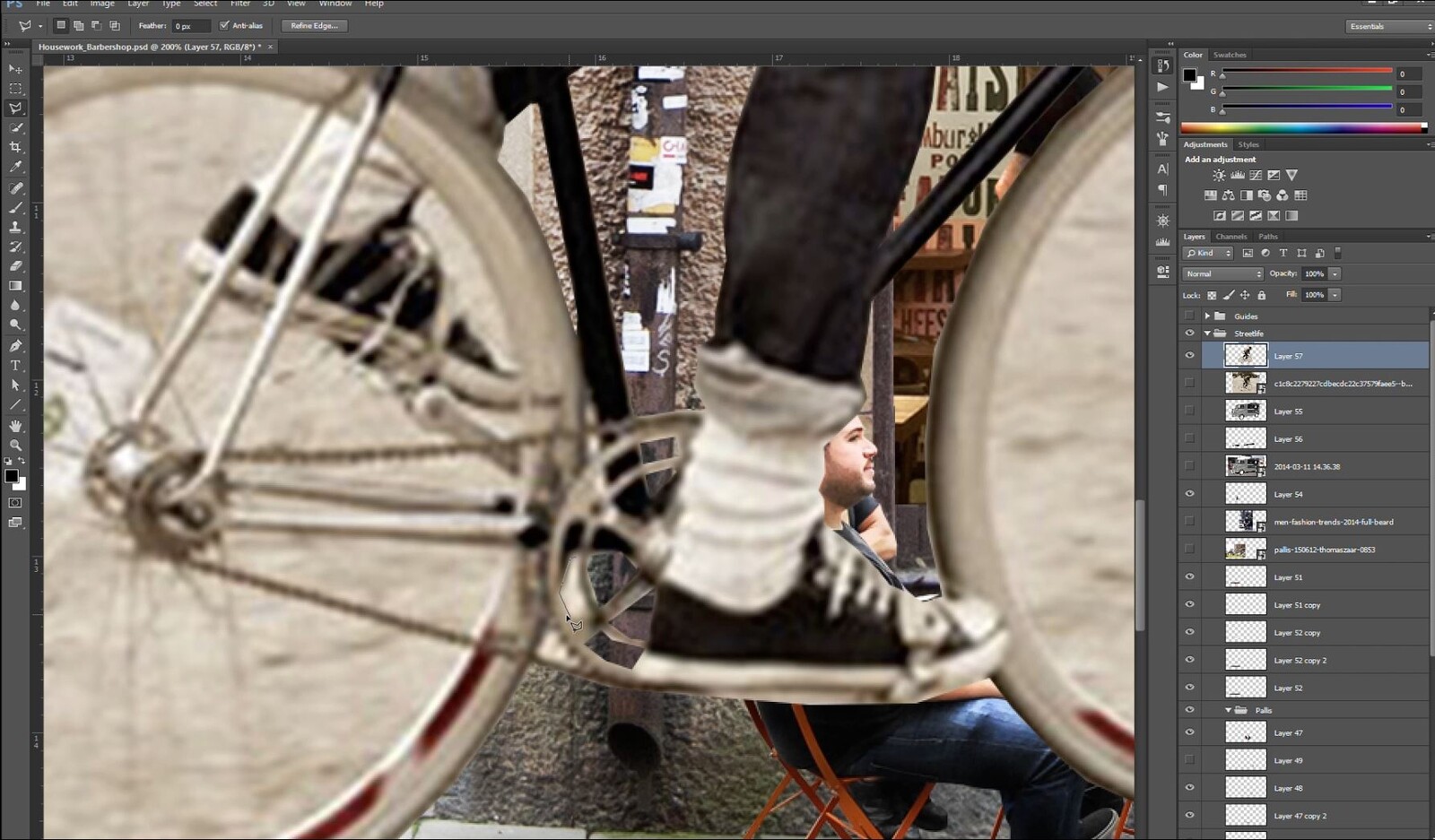

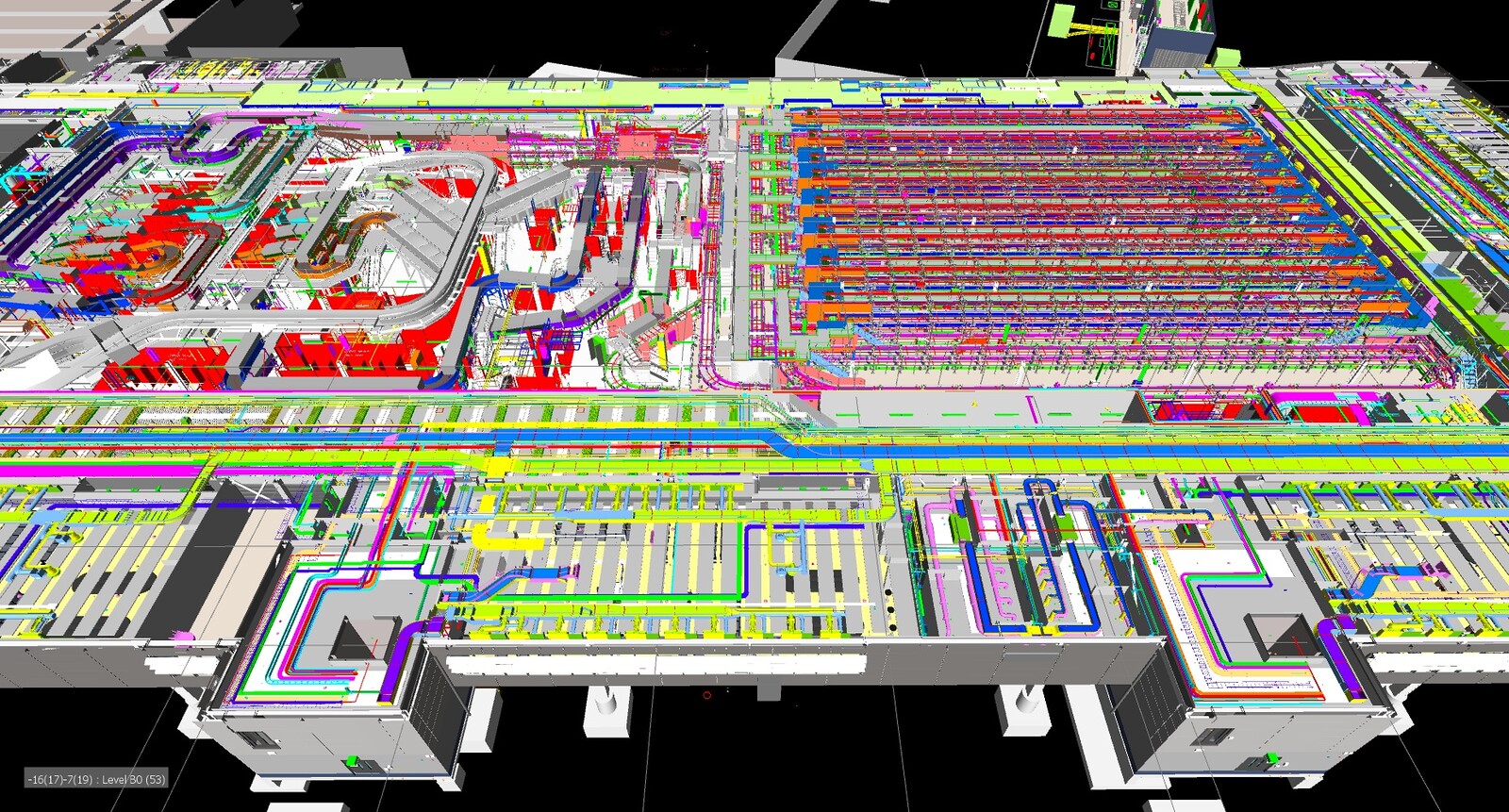

There is a craft in creating polished ubiquity. There is labor: waged, lived hours spent sitting, screen-bound, manipulating and producing images using various pieces of software. There is an embodied, trained knowledge of how to use the tools, and a gut feeling for how far they can be pushed. There are routines and orders in which operations must be performed. And there is a deep concern with the quality of visual information, an archival fussiness over how to retain that quality in the stack of layers making up an image, despite the corrosive consequences of the various operations that can and must be performed.

I am, I have to concede, not a good photoshopper; I’m not even half-good, compared to the architects I work with. It takes me ages to acclimatize to the interface, once I’ve opened the program, and to enter its layered logics. It’s easy to critique the mundane aesthetics of commercial photomontages, but what is harder—especially for bad photoshoppers—is to inhabit the production side of the equation. Smart phones and social media make us feel that we are all visualizers, but the techniques and pressures that define the production of photomontages also define architectural practice and generalized conceptions of the built environment more widely. The production of ubiquity is worthy of our critical attention, despite the boredom that it skilfully induces.

Layer 1: People_Background

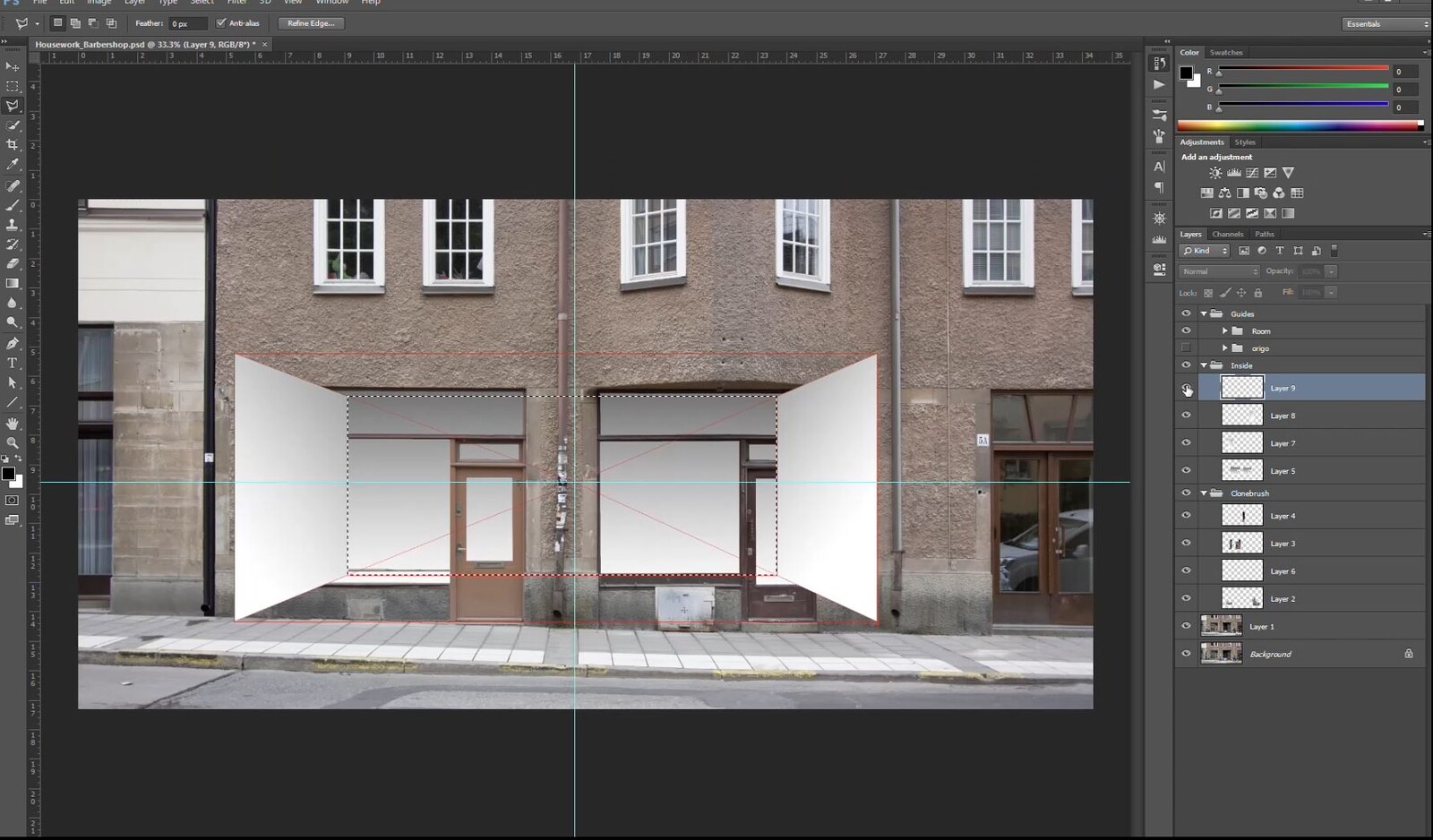

Architectural visualizations are expected to do a whole lot of things. These images have to win competitions, achieve buy-in from clients and financiers, create constituencies and publics for projects, and make a sketchy idea seem credible, despite the fact that they may lack a site, financing, planning permission, structural systems, and inhabitants. Given all of this, it’s suspect how the work of creating digital models from concept sketches, of rendering out images from the model, and then of populating and adjusting those images through the montage techniques of software like Adobe Photoshop, are tasks that are generally outsourced, or if performed in-house, are delegated to non-architects or juniors.

With the advent of platform capitalism, visualization services can also be purchased online. It’s not even uncommon for architecture students to hire remote workers or enlist their friends to perform this “dirty work” on their behalf. While such exchanges might be read as evidencing an admirable collegiality, they also provide evidence of a violent culture of unacknowledged dependency that runs deep within the architecture discipline. We need only recall the figure of Marion Mahony Griffin, whose renders for both Frank Lloyd Wright and her husband Walter Burley Griffin won her little credit and no authorial claims within her own lifetime.

A critical history of architectural visualization would likely reveal a host of artists and illustrators, draftsmen and building designers with vocational training, countless interns and junior architects, and a fair share of wives, friends, and lovers, whose efforts have gone unauthored in the face of the authorial clout of those working on “the building” itself, rather than its rendered and montaged milieu. Even when well-paid and treated as a valorized specialist competence, visualization is traversed by complex economic and gendered relations: it is both a male-dominated tech-boy activity and a domesticated, at times feminized, environmental support system.1 The fact that the term “render bitch” exists illustrates this duality and tension.2 In both cases, visualization is a form of work performed by laboring persons which is largely unsigned and (intellectually and physically) separated from “the architecture” that it depicts and supports.

Layer 2: Adjustments_Gloss

In her recent book Dirty Theory: Troubling Architecture, architect and philosopher Hélène Frichot reminds us that digging into the dirt, staying within the dirt, and getting dirty all constitute important feminist strategies of resistance.3 If visualization must be kept separate from architecture proper because it is “dirty work,” it is ironic that its operations are performed largely to eliminate (digital) dirt and to produce glossy surfaces.

Anyone who’s spent time using Adobe Photoshop knows that the set of operations that make up ‘shopping are highly hygienic in their character. The application, removal, and trimming of “masks” and layers; the attempts to bring light to dark corners through subtle “adjustments”; the manipulation of shadows and reflections to ensure that reflective surfaces shine; as well as the insertion of objects and things in order to furnish spaces and populate surfaces: all of these acts constitute a kind of maintenance of an environment into which “the building” can be inserted. Visualization, in its obsessive polishing, cleaning, tidying, and table-setting is a form of digital housework that operates on, and thereby establishes, architecture’s background.

Writing on the glossy interior urbanism of casinos, museums, and hotels, architect and theorist Hannes Frykholm reminds us that the production of architectural atmosphere “requires repetitive acts of labor that…include the chores of wiping, vacuuming, scrubbing, watering, polishing, brushing, and gardening.”4 “By hiding tasks, tools, and infrastructural support systems in inconspicuous details,” he continues, “under the cloak of night, in backstage spaces and in remote sites of production, atmosphere takes on the appearance of a natural occurrence, similar to a wind brushing through a tree or rain beating on a roof.”5 Obfuscating particular kinds of labor risks depoliticizing that labor. A deliberate refusal to talk about how the lush and glossy spaces of the casino are produced is, Frykholm warns, integral to the production of the mysticized and essentialized “atmospheres” that the architecture discipline’s phenomenological orientations demand.

The parallel between a polished stone floor and a well-rendered and well-‘shopped photomontage is useful. The same dynamics that Frykholm identifies in the rarefied spaces of the lobby are of course present in their rendered digital counterparts. Douglas Spencer recently provided a good example of this in the renders of Bjarke Ingels Group’s speculative proposal for Oceanix City, a UN-Habitat-sponsored archipelagic eco-city concept. Like Frykholm’s work on casinos, Spencer’s critique targets the way in which social interdependencies are necessarily erased in the pursuit of elitist visions of luxury eco-living. “Labor,” he comments, noting the lack of delivery and ITC infrastructures, “can only appear in its most archaic and naturalized forms: gardening or going to the market—precisely the immediate forms of social reproduction that capitalism sought to eliminate from its inception through the imposition of waged labor.”6

As all good feminists know, to relegate conditions to the status of “nature” is all too often to render them unwaged. Once naturalized, unwaged labor is depoliticized, allowing it to be treated as incontrovertible. This effectively forecloses any discussion of changes to the status quo. In the case of the very specifically unwaged and systemically invisible acts of “cleaning” performed by housewives, this foreclosure is performed by making any rejection or revolt against the work seem trivial. As Silvia Federici famously warned: “the assumption that housework is not work has prevented women from struggling against it,” with the only exception being “the privatized kitchen-bedroom quarrel that all society agrees to ridicule.”7 The result of the attempt to resist is scorn and dismissal: “We are seen as nagging bitches, not workers in a struggle.”8 The render bitch does not complain.

Layer 3: Copy_Copy2_aaaaaaargh

Under such conditions, work becomes drudgery. As Frichot observes, with a mild sense of exhaustion: “Housework never comes to an end, but starts over each day. As such, it is ritualized. It is repetition with a vanishing margin of difference. No amount of scrubbing, wiping, brushing, sweeping, mopping will be enough.”9 Visualization falls into the same trap—having to repetitively maintain architecture’s environmental milieu from scratch, with each singular object of architecture requiring the same unique background, its operations become routinized and repetitive.

When understood as a form of digital maintenance, no wonder visualization falls into a state of drudgery, repeating the same tired tropes, offering up the same sunny images or moody snow-filled street scenes, the same child with the same balloon, the same luxury cars, the same verdant interior foliage. “When you commission an image, you send the visualizer a view, a screen grab of the model, showing approximately which view of the building you are after,” commented architect Andreas Nordström, head of competitions at the Oslo-based office Link Arkitektur. “You’re so disappointed when what you get back is exactly that view. You just think: why didn’t you test something else, exercise your artistic freedom? What about challenging the client?!” When asked to describe what he looked for in an image, Nordström conceded: “it has to be true and it has to sell.” Thinking further, he admitted to feeling conflicted. “It’s hard, you know: a visualization is a lie that is trying to be true. So, it always fails. Maybe we’ve reached the limit of usefulness with visualizations? I’ve started to think that if we were to submit proposals without visualizations or try using illustrators instead, then at least it wouldn’t have to pretend to be true.”10

The ubiquity of photomontages is not only the result of visualization’s subjugated status in relation to architecture proper; it is also intimately related to the speculative nature of capital investment. As Nordström hints at in his search for “truth” in the images he commissions, fidelity to existing conditions plays an important role in the success of a photomontage. The architectural project is, after all, a collaborative production, dependent on a range of factors outside of architecture in order to come to fruition, not least the inputs of capital from financiers and of regulatory approval from planners. In order to act upon the world and to convince a range of actors to commit to realizing a project, a project must be “plausible.”11 It must act normal, conforming to what Jean Baudrillard refers to as a society’s “strategy of the real,” or the societal indictment to treat anything that is not flagrantly simulated as if it were real (lest law itself be exposed as the simulation it is).12 The architectural visualization is thus stuck in a bind: it must provide its audiences with an image of a future that does not yet exist, but it also must be as close to “real” as possible. This is a future that must feel familiar and thus be predictable: it must be a future that we can accept as “true” to the extent that we have already seen it, perhaps a thousand times before. The visualization creates the illusion of control over the future by depicting it.

Spencer notes that “the renderings of life on Oceanix never quite succeed, though, in eradicating the appearance of class relations…the figures cast from image banks as the inhabitants of Oceanix fail to convince as equal representatives of a live-work-gather continuum. Instead, the renderings inevitably depict scenes of indifference to exploitation and inequality.”13 Because of the injunction to maintain plausibility, the visualization will always to some degree “fail.” It will never be “true” enough, while at the same time it will never be able to erase all of the traces of its own production.

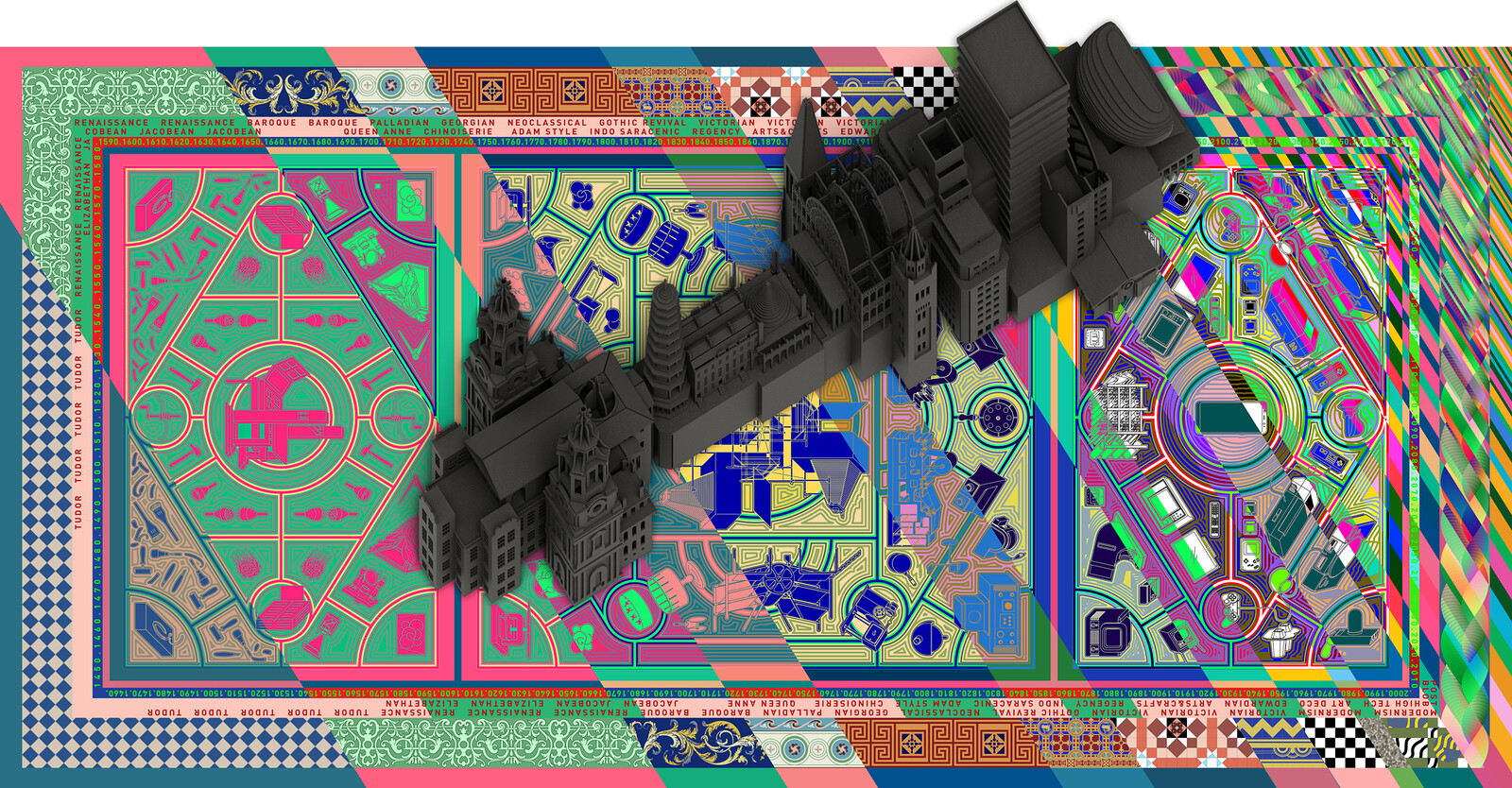

Photoshop of Eileen Gray’s E-1027 House by Katarina Bonnevier, from her 2007 dissertation “Behind Strange Curtains: Towards a Queer Feminist Theory of Architecture.”

Layer 4: Adjustments_GaussianBlur

Architect and educator Brady Burroughs overtly celebrates architecture’s inability to remain faithful to the status quo under the tenets of what she terms “misperformativity.”14 Drawing on Judith Butler’s use of performativity to describe the construction of gender through the repetitive performance of speech acts, Burroughs proposes that misperformativity might be used to flirtatiously queer architecture, thereby making possible the production of other kinds of architecture and other kinds of architects.

Architectural misperformativity could be thought of as doing “the architect” (or “the academic” or “the studio teacher” or “the student”) so wrong, it’s right. In other words, misperformativity is an intentional performance of these expected notions and habits, including architectural critique, in an improper and unserious way, to thwart the seriousness of academic architectural culture and queer it into a critically playful one.

—Brady Burroughs15

Amongst a dizzying array of textual and visual techniques, Burroughs uses photomontage to illustrate an act of flirtation and “misperform” Aldo Rossi’s rowhouses in Mozza, Italy. In an act of renovation that loops throughout the book, traces of fictional inhabitation by various human and non-human figures are photoshopped into interior and exterior photographs of the rowhouses. In this way, Burroughs appropriates this canonical architecture, transforming it into a background, against which she stages her own revolt against the norms that dictate what kinds of bodies and texts architecture can hold.

The space of an architectural visualization can be forced to productively “fail” reality in ways that do not depend on a dialectic juxtaposition, but rather operate on the grounds of a smoothing of interlaced realities.16 Rather than a “renovation”—which implies a material incursion into a space and acts of addition and deletion—we might instead invoke the notion of an “enactment” in thinking through the (mis)performativity of the image. In “Behind Strange Curtains: Towards a Queer Feminist Theory of Architecture,” architect Katarina Bonnevier enacts Eileen Gray’s E-1027 House on the French Riviera, employing an act of flirtatious photoshopping in the process.17 In a text that masquerades as a lecture script, the images are described as “slides.” At one point, the reader is instructed that the book’s protagonist, the lecturer, shows her audience an image of a party staged within the interior of E-1027. The image can be found at the end of the book, and while it is labelled “collaged,” it is clearly made with Photoshop; few attempts have been made to conceal the clash of different eras and elements.

When Bonnevier remarks that “This collage…is a flight of my imagination…It has become a poster for the interconnectedness of actors, acts and built environment that I want to approach in this theory of queer feminist architecture,”18 we can understand that the image here acts as a projection not only in the material sense of an image projected on a wall (it is a lecture slide), but also as a representation that aims to actively move (project) an audience towards an imagined condition. The image of E-1027 depicts an inhabitation of the space which occurs without altering the space per se, but rather by adding that which was previously subtracted from its representation (the queer and wildly excessive aspects of this architecture). In splicing together past, present, and future, it invites us to rethink our role as viewing subjects in relation to architecture and its canon. Bonnevier describes this in terms of the production of a queer gaze which can “dismantle buildings accepted as neutral, non-gendered, frames.”19

Layer 5: Final_final

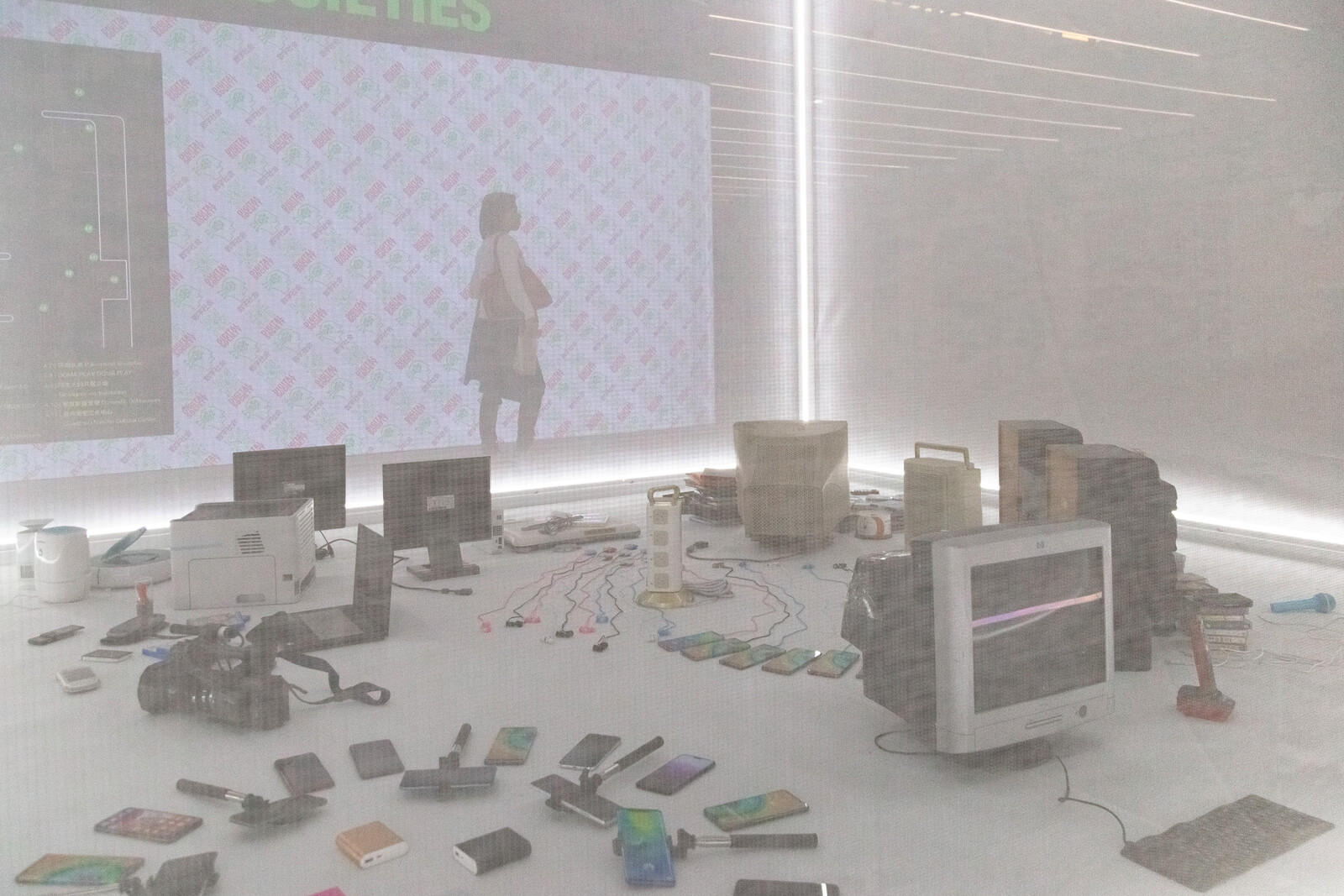

The twenty-first century is characterized by an unprecedented level of visual immersion—we are, it can sometimes feel, drowning in images. I’ve checked my phone countless times during the writing of this piece and regularly been sucked into YouTube-clip spirals and Instagram vortexes. The manic dragging and scrolling of images across our field of view is, we must remind ourselves, also a form of work, and one that is performed daily, hourly, by the minute, through social media. Browsing content is a form of training that formats the ways in which we see the world; producing content almost inevitably entails the use of our bodies and most intimate spaces as props and backdrops. Both are exercises in production (of self and of environment).

Image work is dirty work in its persistent failure to be “true” and its obsessive attempts to clean up. Just as “the assumption that housework is not work has prevented women from struggling against it,” it is difficult to imagine users of social media asserting a political claim for the recognition of their naturalized, depoliticized, and trivialized labor in producing images. And yet a labor politics exists in such acts. Image work—photoshopping, instagramming, facebooking—is not just a form of individualized and domesticated housework, performed by and on the self exclusively, but also a form of collective maintenance with respect to a shared environment. Like architectural photomontages, the images of social media also compose a “background” for everyday life, a milieu into which objects and propositions can be inserted, tested, or (mis)performed. In aggregate, in flow, they may even offer a space wherein other ways of seeing might be trained.

Within the photomontage and its software lies the suggestion that work done in the background of architecture matters; that only in relation to its (ubiquitous, repetitive, boring) context can an architectural object truly shine. The figure of the photoshopper is always stuck in a bind, knowing that the more invisible their work is, the better they have done their job. In this lies an interesting proposition. What would it mean to adopt the photoshoppers’ work ethic, and work on our architecture and our selves as (supportive) backgrounds, rather than foregrounded objects? What software infrastructures might we need to invent and to demolish in order to facilitate such a misperformance of the object and such a willful production of environment?

In February 2020, two of the team of eight at the Bergen-based firm Mir appeared to be women, including none of the two founding partners; at Stockholm-based Walk the Room, three of a team of 18 appeared to be women, including none of the three partners; at of the Paris/Los Angeles/Milan-based Luxigon, six of the team of 26 appeared to be women, including one of the seven partners; at the Paris-based Artefactorylab, 17 of the team of 75 appeared to be women, including one of the seven partners; at the German firm bloomimages, 12 of the team of 34 appeared to be women, including none of the five partners; and at London-based The Boundary, six of the team of 22 appeared to be women, including none of the two founding partners. Whilst not an extensive survey (the attribution of gender based on names, photographs, and LinkedIn is not without problems), it makes it possible to say that European architectural visualization firms appear to be heavily male dominated.

I take this term from visualizer Henry Goss. See Ross Bryant, “The Addition of Real-World Imperfections is Taking Architectural Visualisation to the Next Level,” Dezeen, August 12, 2013, ➝; or, alternately, see the URL “www.renderbitch.com” which redirects to Goss’s current practice, The Boundary, ➝.

Hélène Frichot, Dirty Theory: Troubling Architecture (Baunach: Spurbuchverlag, 2019).

Hannes Frykholm, “Building the City from the Inside: Architecture and Urban Transformation in Los Angeles, Porto, and Las Vegas” (PhD Diss., KTH Royal Institute of Technology, forthcoming 2020), 336.

Ibid., 338.

Douglas Spencer, “Island Life,” Log 47 (Fall 2019).

Silvia Federici, Wages against Housework (Bristol: Power of Women Collective and the Falling Wall Press, 1975), 2–3.

Ibid.

Frichot, Dirty Theory.

Andreas Nordström, personal communication with the author, Oslo, February 6, 2020.

Helen Runting, Rutger Sjögrim, and Fredrik Torisson, “Pop Theory: The Architecture of Late Night Shopping,” Architecture and Culture 5, no. 3 (2017): 513–524.

Jean Baudrillard, Selected Writings, trans. Mark Poster (Cambridge: Polity, 1988).

Spencer, “Island Life,” 173.

Brady Burroughs, Beda Ring and Henri Beall, “Architectural Flirtations: A Love Storey” (PhD diss.: KTH Royal Institute of Technology, 2016).

Ibid., 92, 94.

See: Hannes Frykholm, “Smooth Montage,” in Architecture in Effect 2: After Effects, eds. Hélène Frichot with Gunnar Sandin and Bettina Schwalm (New York and Barcelona: Actar, 2018).

Katarina Bonnevier, “Behind Straight Curtains: Towards a Queer Feminist Theory of Architecture” (PhD diss.: KTH Royal Institute of Technology, 2007), 34.

Bonnevier, “Behind Straight Curtains,” 34.

Ibid., 30.

Software as Infrastructure is a project by e-flux Architecture as part of “Eyes of the City” at the 2019 Bi-City Biennale of Urbanism\Architecture (Shenzhen).