The Communist bosses of Peiping dropped a bamboo curtain, cutting off Peiping from the world.

—Time magazine, March 14, 19491

After World War II, the geopolitical logic of the world system shifted. Where Great Britain (and other colonial powers) had previously secured hegemony by controlling access to investment capital and manufacturing technology, the United States and the Soviet Union relied on economic aid and technological assistance to further their political goals. The main arena for “superpower” competition was Europe, even though proxy wars were fought elsewhere. Indeed, during the Cold War, “East” and “West” referred to Europe, rather than to Euro-America (“the Occident”) and Asia (“the Orient”) as they had during the Colonial Era. The Soviet Union promoted its interests by investing in Eastern Europe, while the United States advanced its cause in Western Europe. Importantly, outside of Western Europe, the second most important arena for US investment was East Asia, especially Japan. In the Japanese model of industrial modernization, the government coordinates the construction of infrastructure, including the development of container ports, the acquisition of investment capital, worker training, and managing social transitions. The governments of Hong Kong, Singapore, South Korea, and Taiwan quickly adopted the Japanese model of modernizing through industrialization. All five countries saw “miraculous” economic growth during the 1970s, dominating key industries, modernizing everyday life for ordinary citizens, and emerging as the third pillar of the industrial world.2

In 1949, the Communist part of China (CPC) gained control of the Chinese Mainland, forcing Nationalist (KMT) forces to flee to Taiwan. That year, the CPC established the People’s Republic of China (PRC), while the KMT established the Republic of China (ROC). While Taiwan was integrated into US geopolitical strategy, the PRC followed the Soviet model, adapting a command economy to expedite modernization.3 China’s national plan established prices, wages, and assigned output quotas; managers and workers were evaluated in terms of their ability to fulfill plan objectives. The plan was (and remains) overseen by the Politburo and managed by planners in Beijing.4 In addition, during the Mao era (1949–1976), bureaucratic controls on consumption allowed the government to accumulate a high proportion of national production for reinvestment in target industries. China’s planned economy incorporated a geopolitical logic, too. Industrial manufacturing was located in cities, while agriculture was located in rural areas and organized into collective and state farms. There was limited mobility between urban and rural areas, and both cities and farms were ranked according to productive capacity. In the immediate post-Mao era, China’s reform and opening up policies aimed to transform China into a richer version of itself without risking the overthrow of the Communist Party of China (CPC). To this end, the political logic of Chinese reforms entailed developing economic strategies within the country’s national plan.

At the same time that China embarked on economic reforms, the Cold War world order was also poised to step out into the same river of change, even if this conjuncture only became apparent in retrospect.5 Located on the “bamboo curtain” at the Sino-British border, Shenzhen’s spatial liminality facilitated national political and economic restructuring, which ultimately had international effects. In the ordinary order of things, liminal spaces have recognizable thresholds and boundaries; one crosses from one side to the next. Most liminal spaces are located at the edges of mainstream society. In contrast, the geopolitical logic of Shenzhen has been to place liminal spaces at the center of society, making perpetual transformation—of the self, the nation, and the world—a key feature of the model.6 The transformation of Luohu-Shangbu from a riparian society into the earliest iteration of the Shenzhen Special Economic Zone (SEZ) can give a sense of how liminality was deployed to as metaphor and strategy. Today, the Luohu area is known as Dongmen, a bustling cross-border shopping district, and Shangbu is known as Huaqiangbei, the world’s “Silicon Valley of Hardware.”

Chen Yun and Deng Xiaoping share a laugh, 1952.

Political Liminality: “Feeling Stones to Cross the River”

During the Working Conference of the CPC Central Committee in December 1980, Politburo standing committee member Chen Yun coined the phrase “feeling stones to cross the river (摸着石过河),” which describes a decision to move forward when outcomes are unknown, to caution against excessive liberalization. In retrospect, Chen Yun presciently feared what eventually happened to the Soviet Union in 1991—the fall of the Communist Party and the collapse of the state apparatus. Later in that same conference, Deng Xiaoping reinterpreted this phrase to refer to the courage to take action. “Feel theory (摸论)” quickly became one of three main theories of China’s reform era.7 Forty years later, the expression remains one of the main themes in Chinese descriptions of how early reforms were implemented, usually to emphasize that during the first decade of reform and opening up, no one knew what they were doing. As metaphor, “feeling stones to cross the river” figured the transition from the planned economy to a market economy, where reform and opening up policies would be the “stones” that would allow the nation to cross from the river banks of socialism to whatever might come after. For Chinese leaders, the debate was over which “stones” should be used to advance the socialist project. Chen Yun advocated a “bird-cage” economic system, in which the bird (economic activity) would be given more freedom but never allowed to escape from the cage (the planned economy). In contrast, Deng Xiaoping promoted more extensive market reforms, which he believed would not only improve economic performance and raise the standard of living, but also generate political advantages through alliances with local officials, intellectuals, and the military.8

In practice, the “stones” of market reform included promoting the profit motive, competition, and managerial autonomy into extant state-owned enterprises and integrating market exchange between economic units. Reforms also allowed for the existence of non-state economic actors (“entrepreneurs”) to exist alongside—but not replace—emergent socialist markets.9 In other words, although the implied subject of “feeling stones to cross the river” was the Chinese nation, in practice, government policies including ongoing support for state monopolies and state-owned enterprises to insure that the CPC survived the post-Mao transition.

The expression “feeling stones to cross the river” illustrates the concept of liminality, which was first put forward by Arnold van Gennep at the turn of the twentieth century and subsequently reintroduced into anthropology by Victor Turner in the 1960s.10 Although liminality has both temporal and spatial dimensions, it is primarily conceptualized spatially. In the case of “feeling stones to cross the river,” space serves as a metaphor for historic transformation. Transformation begins here and now on the first river bank (the extant socialist system), while the river (the liminal space) represents what needs to be passed through in order to reach the other bank (what comes next). The time it takes to cross the river is implied and uncertain; some will cross quickly and others slowly, and some will not make it across. This metaphor makes clear how liminal spaces are simultaneously individual and social. On the one hand, individuals pass through liminal spaces “betwixt and between” two social roles; “they become nameless, timeless and socially ‘unstructured,’ existing in a floating state of being, even as they acquire throughout the liminal period the necessary knowledge and experience in order that their transformed beings may eventually re-enter society and take up their new roles.”11 On the other hand, liminal spaces resonate socially. Positioning stones is an intentional use of space that facilitates passage across the river, reduces the risks of crossing, determines where passage occurs, and places liminality and its risks within a larger social framework. This in turn makes something as banal as crossing a river culturally meaningful.12

Map showing the location of Special Economic Zones (SEZs) and Open Cities in China, 1997.

Luohu-Shangbu: The Liminal Origins of the Shenzhen SEZ

The economic logic of “feel theory” was simultaneously political and spatial: the government would place “stones”—favorable policies, factories, and urban infrastructure—in specific locations to connect Chinese manufacturers to international markets in order to raise domestic productivity and standards of living. Chosen sites were explicitly liminal spaces within the extant Cold War Order. The first four SEZs—Shenzhen, Zhuhai, Shantou, and Xiamen incorporated Cold War borders into site selection and urban planning. Located just north of Hong Kong along the Sino-British border, for example, Bao’an County was elevated to Shenzhen City in 1979 and the SEZ was established in 1980, abruptly repurposing the Sino-British border from its Cold War function as the “bamboo curtain,” where one crossed from capitalism to communism and back again, to a regulatory check point between trade partners.13 Shantou boasted extensive connections to Overseas Chinese communities throughout southeast Asia; Xiamen is located west of Taiwan; and Zhuhai is located north of Macao. The location of the four SEZs not only gave SEZ manufacturers access to technology and trade resources, but also reduced the costs that East Asian investors would incur outsourcing production.14

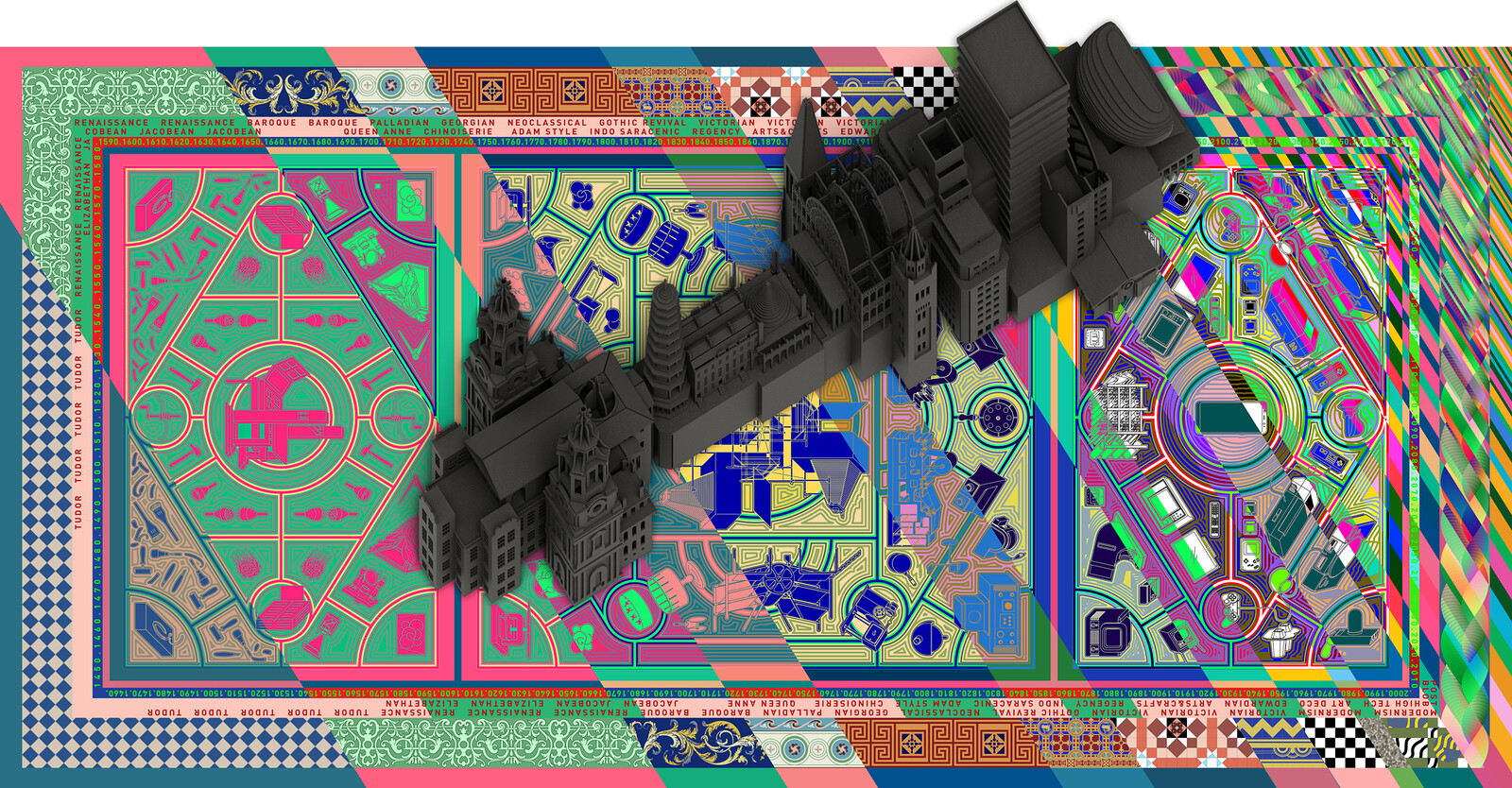

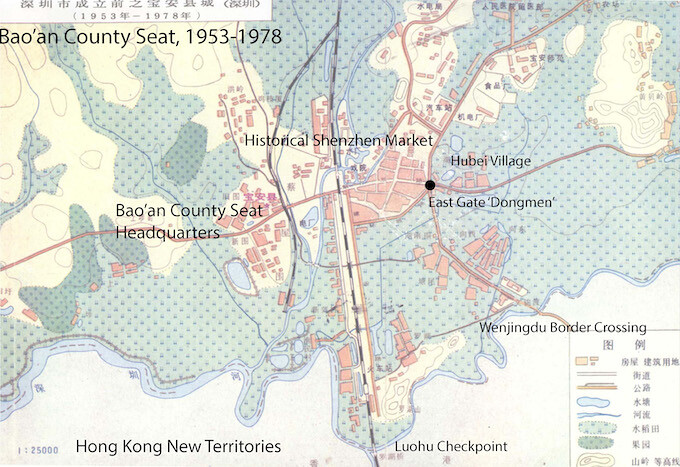

The earliest construction of the Shenzhen SEZ combined two Management Districts (管理区), Lou and Shangbu, anticipating Shenzhen’s place “in between” China and the World.15 In terms of administrative territory, Luohu referred to roughly the same territory as present-day Luohu District, and Shangbu referred to the territory of present-day Futian District.16 Luohu-Shangbu catalyzed China’s transition from a planned to a market economy through the construction of two different, but integrated kinds of markets. Luohu referred to cross-border commence that was encouraged in and around the historical Shenzhen Market (present-day “Dongmen”) and the cross-border supply stations at Wenjindu—markets as spaces of consumption. In contrast, Shangbu was originally sited as an industrial new town, where “markets” referred to the organization of global production chains. In other words, Louhu was a physical market, while Shangbu was planned according to the market principles that Deng Xiaoping and Chen Yun were debating in Beijing. Luohu evolved into a dense commercial network, comprising old village housing and alleyways, new malls and shopping spaces, and residential areas. Indeed, China’s first McDonald’s opened in Dongmen in 1990.17 In contrast, Shangbu was a planned new town, including a city hall, cultural infrastructure, residential areas, and tourist sites. Shangbu also built two industrial parks—Bagualing and Shangbu. State-owned enterprises set up factories in the two parks, where they produced electronics for global markets and benefited from privileged access to land, talent, supplies, and overseas shipping. However, as they used to say in Shenzhen, “plans can’t keep up with change.” By 1990, Bagualing would be evolving into a center for high-end printing, while Shangbu would have already begun its transformation into the Huaqiangbei electronics area.

Spatial Liminality: Arbitraging the Sino-British Border

Historically, Luohu and Shangbu were part of the Shenzhen River Valley, a cultural area that corresponds roughly to the territory of present-day Luohu and Futian Districts and the Hong Kong New Territories (NT). The two most important markets on the river, Shenzhen and Yuen Long, were located on its upper and lower reaches, respectively. There were ferry crossings at both Luohu and Shangbu (for access to Shenzhen Market) and across Shenzhen Bay (for access to Yuen Long). In fact, “Shangbu” is a Cantonese expression meaning “pier” or “dock,” and there were two piers in the Shangbu section of the Shenzhen River—Shangbu and Chiwei. Traditional villages in the Shenzhen River valley built their homes beyond the riparian flood plain, cultivated rice, peanuts, and vegetables, grew lychees on the surrounding hills, and constructed fishponds along the river banks.

In 1898, the Sino-British border was drawn along the hide tide mark of the northern banks of the Shenzhen River. The earliest effect of the border was to give markets on the British side of the border a competitive trade advantage. Because the border had been drawn at the high tide mark of the northern banks of the river, all piers on the Shenzhen River were technically in Hong Kong territory. In practice, this meant that goods which left from the northern banks to be sold at Yuen Long and other NT markets were not subject to international taxes.18 In contrast, the Luohu piers were located about a kilometer from Shenzhen Market, meaning that goods transported to and from the market via the Luohu docks were subject to import and export taxes. The construction of the Kowloon-Canton Railway (KCR, 1906–1911) further intensified the effects of the border on local society. Before 1950, the railway passed from British to Chinese territory via the Luohu Bridge, which had replaced the Luohu Ferry crossing. Until the closing of the Sino-British border at the start of the Korean War, circa 1950, Shenzhen station served as the last station on the British side of the KCR, extending the practical border further inland.19 After the establishment of the People’s Republic, the Chinese side of the railway was nationalized and Luohu Bridge eventually became a physical instance of the bamboo curtain, where one passed from capitalism to communism and vice versa.

In 1953, the Bao’an County Seat was moved from Nantou (on the Pearl River) to Caiwuwei, which was located next to Shenzhen Market. The move not only allowed for more direct management of the border, it also anticipated the emergence of the area as a liminal space between China and the world. For example, throughout the Cold War, cross-border initiatives such as the East River Shenzhen Waterworks Project resolved Hong Kong’s chronic water shortages, enabling Hong Kong to industrialize.20

Map of Bao’an County Seat, 1953.

The construction of Shennan Road illustrates how the construction of the SEZ redeployed Cold War resources to achieve market aims. During the Cold War, Bao’an County headquarters were located on the western side of the KCR railway and connected to Shenzhen Market via Liberation Road, a 2.1-kilometer-long, roughly seven-meter-wide gravel road. Like the path from the Luohu docks to Shenzhen Market, Liberation Road facilitated passage between two fixed endpoints. Shennan Road eventually displaced this landscape, intensifying the effects the Sino-British border on local society. As the city’s main east west artery, Shennan Road became a series of liminal spaces which comprised both hard and soft borders. Construction of Shennan Road began in 1979 and ran parallel to the Shenzhen River, merging with Liberation Road at Hongling Road, which was the Luohu-Shangbu border. By 1994, Shennan Road was a 25.6-kilometer-long boulevard that traversed the entire SEZ. At the Nantou Checkpoint on the city’s internal border (the “second line”), Shennan Road became National Highway 107, connecting the SEZ to the industrial parks of New Bao’an County.21 In terms of Shenzhen’s earliest industrial planning, this urban form was known as “store in front, factories in the back (前店后厂)” and “attract outside resources, link-up with interior resources (外引内联).” The structure of these place descriptions repeated (and intensified) the geopolitical logic of establishing the SEZ at the Sino-British border and the development of Luohu-Shangbu, where Luohu and Shangbu were treated as complementary areas within one liminal space to accelerate economic development.

This is not to say Shenzhen River ceased to function as a transportation route. In 1984, the Shangbu and Chiwan piers were consolidated into the Shangbu Docks, which were located at the site of the Chiwei pier. During the 1980s and 1990s, almost 90% of the concrete, bricks, glass, and wood that were used to build factories, offices, and housing in Luohu-Shangbu were shipped from PRD cities and towns via the Shangbu Docks, which were not closed until 2014.22

Economic Liminality: Combining Plan and Market

In addition to redeploying the Sino-Biritish border, the construction of Shenzhen also redeployed the administrative distinction between the state and non-state sectors of the Chinese economy. On Chen Yun’s interpretation, this was known as “combining plan and market.”23 The relationship between these two sectors was itself a transformation of the geopolitical logic of the Cold War, when the world had been divided into competing blocs. During the Cold War, transnational links were forged within blocs in order to maintain their separation. In contrast, the geopolitical logic of Luohu-Shangbu simultaneously intensified links within and between geopolitical units. In its emergent form, this post-Cold War model arbitraged border crossing to stimulate economic growth. As Chinese capital, technology, and people began moving between communist and free world blocs, they also began moving between state and non-state sectors of the economy. This movement allowed state resources to simultaneously exist as plan resources and market commodities, giving state-owned enterprises privileged access to resources that could be transformed into commodities rather than deployed according to the plan.

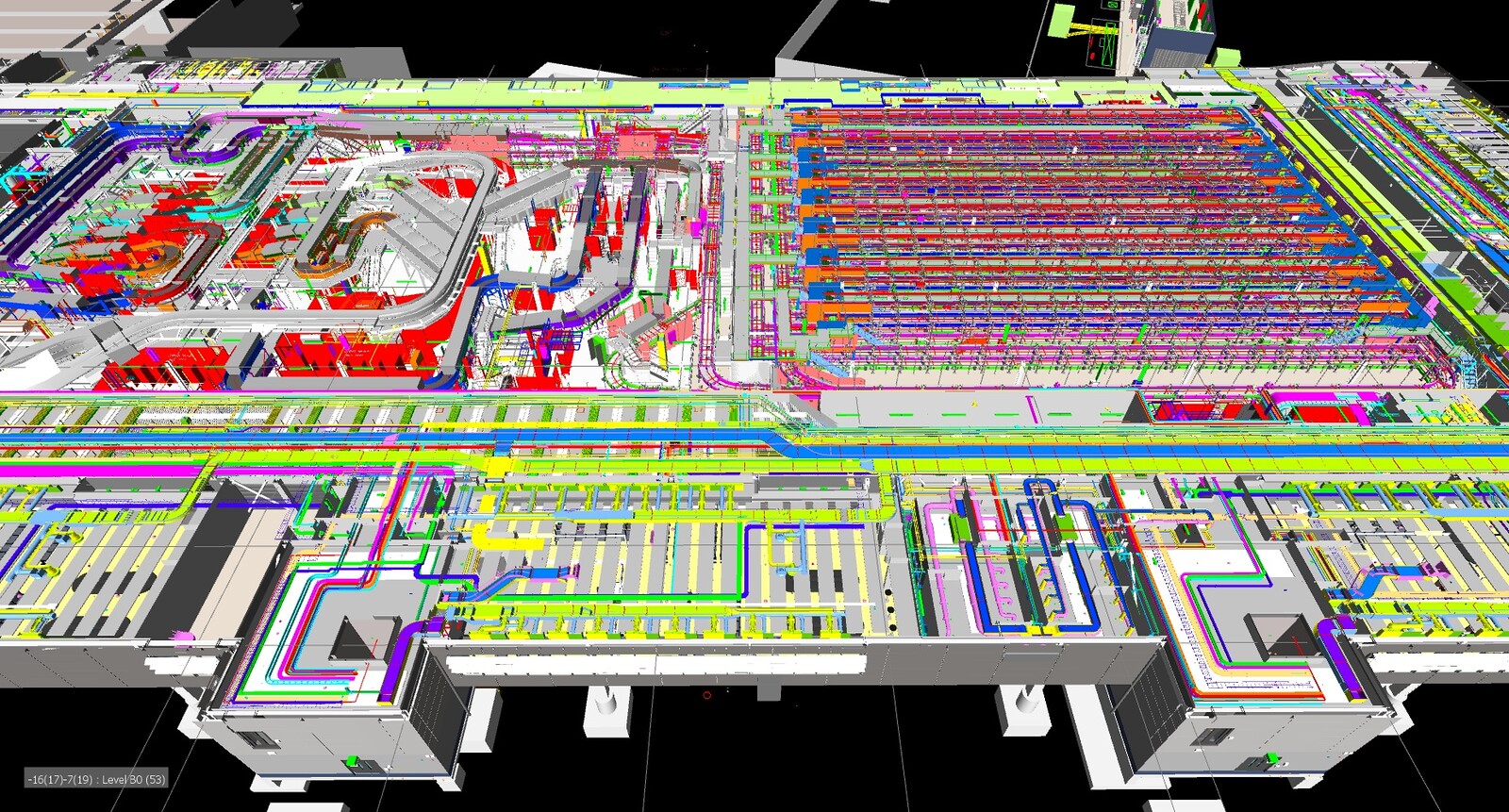

Export-oriented manufacturing facilitated the shuffle of capital, goods and people between state and market, communist and free world blocs. The Shangbu Industrial Park, for example, occupied 0.8 square kilometers of the Shangbu Management Area. When construction of the industrial park began, Shangbu Brigade comprised seven village settlements, rice paddies, orchards, and fishponds which stretched into the Shenzhen River. The state appropriated the land (征用), giving village collectives compensation and settlement areas within their traditional land. When basic construction of Shangbu Industrial Park was completed circa 1985, the industrial park stretched from Shangbu Road in the east to Huafu Road in the west, and from Shennan Road in the south to Hongli Road in the north. The Shangbu “new villages” were located south of Shennan Road, where they were developing support services, markets, and entertainment areas for the new town and visiting Hong Kong investors.24

Shangbu Industrial Park held a strategic position within the new downtown area, and its eastern border served as the unofficial gateway into “Shenzhen.” Early pictures of the intersection of Shennan and Huafu Roads show that the city’s main road narrowed immediately after exiting Shangbu. The new city hall was located on the block adjacent to the park’s eastern border, and a new residential and living area was located just north of the industrial park. Consequently, workers in Shangbu had easy access to Shenzhen Number 2 Hospital (formerly Honghui Hospital) and Shenzhen Children’s Hospital, Shenzhen Experimental School, Shenzhen Library, and the Shenzhen Grand Theater, as well as Bijia Mountain and Lychee Parks.

Just as the activation of cross-border markets enabled the bamboo curtain to be redeployed for market purposes, the redeployment of Cold War landscapes and technology allowed for the development of capitalist enterprises in Shenzhen. After the Sino-Soviet split in 1961, China found itself perilously positioned between the Soviet Union in the north and American proxies on its eastern seaboard. The Gulf of Tonkin incident (1964) convinced Mao Zedong that China’s nascent manufacturing industry should be moved away from the country’s northern and coastal borders to its “Third Front,” the mountainous areas of its central provinces. From 1964 until the mid-1980s, when reforms were extended beyond the SEZs to China’s fourteen coastal cities, constructing the Third Front was one of China’s most important national projects. At the peak of the movement, China allocated more than 40% of its total investment in capital construction to the Third Front. In addition, four million workers and cadres were deployed to there, with an additional ten million workers migrating to 1,100 large and medium-sized industrial and mining enterprises, research institutes, colleges, and universities.25 Within the Third Front region, the economic returns on industrial projects were less important than relative safety from airstrikes and long-distance nuclear missiles.26

Third Front firms represented one-quarter of China’s military firms and one-third of its workers, integrating large-scale manufacturing capacity, research institutes, transportation networks, and skilled personnel into national conglomerates. Some of the most sophisticated industrial firms in the country were located in the country’s hinterlands. Nevertheless, despite persistent state investment in Third Front industries, their unfavorable location meant that they were not economically viable. In 1978, Deng Xiaoping was already planning on introducing market reforms into military firms, shifting at least half of the workers to civilian production. The goal was not simply to satisfy consumer demand, but instead to keep millions employed, to use idle plant capacity, and to earn funds for the military. The industries targeted for conversion included the nuclear, aerospace, aeronautics, electronics, ordnance, and shipbuilding. By 1979, restructuring military production was considered indispensable to economic reforms, and the Politburo had decided to deploy military science and technology to the project of modernization.27

In 1979, three Third Front enterprises from northern Guangdong were reorganized as the Huaqiang Electronics Company. Huaqiang workers were transferred to Shenzhen, where they began construction of the Shangbu Industrial Park. They were subsequently joined by workers from other military firms as well as ministries, commissions, and provincial firms in laying the roads, water mains, electrical and telecommunication lines, drainage, sewage, and gas pipes and connecting them to municipal infrastructure, which was being placed by the Corps of Engineering. They also reclaimed low-lying areas and removed Shangbu Hill. These enterprises were given land inside the industrial park, where they—as they had in China’s mountainous hinterlands—built compounds (大院), which were walled off from the surrounding area and only accessible from a main gate. Dormitories for workers and apartments for management and their families, as well as guesthouses and canteens were built inside the walls.28 Inside the industrial park, street names reflected these national goals: Huafu (“China Gets Rich”), Huafa (“China Develops”), Zhenhua (“Invigorate China”), Zhenxing (“Revitalize”), and Huaqiang (“China Strengthens”).

The combination of state and non-state factors made the Shangbu Industrial Park a liminal—and hence viable—economic space. Three features of these earliest firms highlight how non-state market “stones” were integrated into transplanted Third Front firms. First, the transfer of goods, equipment, and technology within the company could be marketized. In this case, market instruments were the “stones” that connected company departments, allowing the firms to maintain their status as state-owned enterprises even as they became profit-seeking entities. Second, capital investment came from cooperation between these firms and foreign companies. State-sector investment included technology, labor management, and appropriation of rural land at nominal costs, while foreign firms provided capital, components, and access to international markets. In this case, cooperative production agreements were the “stones” that allowed movement between Chinese and foreign firms. Third, the firms employed full-time and temporary workers. Firms provided legal residence in Shenzhen, subsidized housing, medical insurance, and school placements for children to full-time workers. In contrast, temporary workers had quasi-legal status in the city and did not have access to subsidized housing, medical care, and the school systems. Here, China’s household registration laws (户口) were the “stones” that enabled firms to move between socialist to capitalist production relations. Today, however, the successful implementation of market mechanisms has meant that permanent employees have been increasingly treated as “temporary,” as housing and medical care are no longer fully subsidized.

Even as construction of the industrial park was completed, non-state actors entered Shangbu via market relationships, specifically property rentals, the establishment of actual markets throughout the park, and increasing leisure consumption. On the one hand, the industrial park was conveniently located in downtown Shenzhen, and although rentals were cheaper than in Luohu, they were higher than outside the SEZ. In the late 1980s, for example, both Huawei and Foxconn chose to open large campuses outside the SEZ in Bantian, a subdistrict of Buji, while labor-intensive industries were already relocating from Shangbu. On the other hand, electronics-related business offices and wholesale markets were set up throughout the industrial park, most famously the Saige Electronic Components market, which opened at the intersection of Huaqiangbei and Shennan Roads in March 1988. Huaqiang rented stalls to entrepreneurs who sold components, repaired electronics, and increasingly built and designed telecommunications products. These non-state companies mediated between suburban factories, foreign investors, and electronics consumers, shoring up the viability of China’s state-owned industries, which operated as landlords by lengthening the production chains that sutured China’s hinterlands to world markets.

1990: The Cusp of the Post-Cold War World Order

The construction of Luohu-Shangbu during the 1980s intensified spatial and economic liminality, not only promoting economic growth but also shoring up the Chinese state apparatus. On the one hand, cross-border commerce and trade expanded the Sino-British borderlands from the Luohu Bridge and Wenjingdu checkpoints to all of Luohu-Shangbu via market relations. On the other hand, marketization did not lead to the dismantling of state-owned enterprises, but rather to their transformation into corporate landlords that had privileged access to domestic resources, technology, and labor. This meant that by 1990, when the Shenzhen government restructured, dissolving the Shangbu Management Area and placing it within Futian District, the SEZ economy operated within proliferating liminal spaces—bonded zones, township enterprises, and urban villages, even as the state sector continued to incorporate larger markets and market instruments into its structure. The transition of Third Front firms from manufacturers to Shangbu landlords encapsulates this process.

During the 1990s, as reforms spread from the SEZ into Shenzhen’s outer districts and hinterland, the Shangbu Industrial Park was increasingly used for commercial purposes. This was especially true as rents increased in Dongmen and public transportation between Luohu and Shangbu improved. Although the Saige electronics market opened at the intersection of Shennan and Huaqiangbei Roads in 1988, it was the 1995 opening of Women’s World that catalyzed the deindustrialization of Shangbu Industrial Park. Shoppers who had previously gone to Dongmen increasingly came to Huaqiangbei Road. During the 1990s, the Shangbu Industrial Park became an intensely mixed-use space as commercial shops occupied the first and second floors of factories along Huaqiangbei Road and industrial-scale entertainment such as bowling alleys occupied upper floors. Throughout the rest of the Shangbu Industrial Park, factory compounds were repurposed as offices, storage facilities, large entertainment centers, and dormitories and housing, which was occupied by entrepreneurs who came to take advantage of the area’s access to electronics components. By 2000, the electronics markets near and along Huaqiangbei Road had become the “storefront” to country’s booming cellphone and shanzhai electronics manufacturing industry. Indeed, by the time Shenzhen the reputation of being the “Silicon Valley of Hardware,” the Shangbu Industrial Park was known as “the Huaqiangbei Electronics area” and the state’s control over the economy has increased via the rents that these liminal spaces generate.29

According to I. Willis Russell, Time magazine was the first to use the expression “bamboo curtain” analogously to Churchill’s use of the “iron curtain.” Cited in Fifty Years Among the New Words: A Dictionary of Neologisms, ed. John Algeo (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993), 126.

See Marc Levinson, The Box: How the Shipping Container Made the World Smaller and the World Economy Bigger (Princeton and London: Princeton University Press, 2006); Ezra Vogel, The Four Little Dragons: The Spread of Industrialization in East Asia (Cambridge and London: Harvard University Press, 1991); David Harvey, The Condition of Postmodernity: An Enquiry into the Conditions of Cultural Change (Cambridge: Blackwell, 1990).

Tensions between the countries grew after Nikita Khrushchev denounced Stalin in 1956, and in 1961 the PRC formally denounced “revisionist traitors” in Moscow. For a discussion of the consequences of the Sino-Soviet split, see Lorenz M. Luthi, The Sino-Soviet Split: The Cold War in the Communist World (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2008).

Since 1992, China has increasingly used market mechanisms to regulate the economy, using the plan to determine strategic goals and investment. China’s first five-year plan was passed in in 1953 and its thirteenth five-year plan was approved in 2019, setting economic goals and strategies for the 2020–2025 period.

Giovanni Arrighi, Adam Smith in Beijing: Lineages of the Twenty-First Century (London and New York: Verso, 2007).

See Mary Ann O’Donnell, Winnie Wong, and Jonathan Bach, “Introduction,” in Learning From Shenzhen: China’s Post-Mao Experiment from Special Zone to Model City, eds. Mary Ann O’Donnell, Winnie Wong, and Jonathan Bach (Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, 2017), 1–19; Mary Ann O’Donnell, “What the Fox Might Have Said About Inhabiting Shenzhen: The Ambiguous Possibilities of Social- and Self-Transformation in Late Socialist Worlds,” TDR/The Drama Review 50, no. 4 (Winter 2006): 96–119.

The three theories were: “cat theory (猫论),” “don’t debate theory (不争论),” and “feel theory (摸论).” Like feel theory, cat theory and don’t debate theory were important to how early reforms were conceptualized, debated, and promoted. In his defense of using capitalist instruments to create Chinese markets, for example, Deng Xiaoping argued that, “It doesn’t matter if the cat is black or white. Any cat that catches rats is a good cat.” Similarly, he put forward don’t debate theory in response to internal Party concerns over whether or not reforms belonged to the socialist or capitalist clan (姓社姓资). The point was to get on with the practical work of developing the economy.

Members of China’s first generation of revolutionary veterans, Deng Xiaoping and Chen Yun cooperated to remove Hua Guofeng from power in order to reform the Chinese system. However, the two men represented radical and conservative approaches to reforming Chinese markets. For a nuanced discussion of their relationship, see Susan L. Shirk, The Political Logic of Economic Reform in China (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1993).

Barry Naughton, Growing Out of the Plan: Chinese Economic Reform, 1978–1993 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995).

Bjørn Thomassen, Liminality and the Modern: Living Through the In Between (Surrey and Burlington: Ashgate, 2014).

Ibid., 92.

Van Gennep begins his analysis of ritual with descriptions of thresholds, demonstrating that spatial and geographical progression correlates with a cultural passage, see Arnold van Gennep, Rites of Passage, trans. Monika B. Yizedom and Gabrielle L. Caffee (Chicago: University of Chicago, 1960). For more on how physical experiences provide the metaphorical grounding for emotional and cognitive experiences see George Lakoff and Mark Johnson, Metaphors We Live By (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1980).

See Joshua Bolchover, “Border Ecologies,” in Border Ecologies: Hong Kong’s Mainland Frontier, eds. Joshua Bolchover and Peter Hasdell (Basel: Birkhauser, 2016), 9–25; Matthew Hung, “Timeline,” in Border Ecologies: Hong Kong’s Mainland Frontier, eds. Joshua Bolchover and Peter Hasdell (Basel: Birkhauser, 2016), 26–34.

See Jianfa Shen, “Cross-Border Connection between Hong Kong and Mainland China under ‘Two Systems’ Before and Beyond 1997,” Geografiska Annaler 85 (2003): 1–17; Weiping Wu, “Proximity and Complementarity in Hong Kong-Shenzhen Industrialization,” Asian Survey 37, no. 8 (1997): 771–93.

More recent examples of this geopolitical logic include the China (Guangdong) Pilot Free Trade Zone, Qianhai & Shekou Area of Shenzhen (est. 2015, ➝) and the Shenzhen Shantou Special Cooperation Zone (est. 2011).

Based on the 1980 draft plan, the 1982 Shenzhen Special Economic Zone Comprehensive Plan proposed a tripartite division of the SEZ into eastern, central, and western clusters. Luohu-Shangbu was the new city’s central—and therefore most important—cluster. In the east, Shatoujiao had been an important cross-border market since the establishment of the Sino-British border in1898. In the west, Nantou boasted the longest urban history of any area in Shenzhen. It was established over 1,700 years ago as part of the government salt monopoly and became the County Seat of Xin’an during the first year of the reign of the Wanli Emperor (1573). See Luxin Huang and Yongqing Xie, “The Plan-led Urban Form: A Case Study of Shenzhen,” 48th ISOCARP Congress (2012); Mee Kam Ng and Wing-Shing Tang, “The Role of Planning in the Development of Shenzhen, China: Rhetoric and Realities,” Eurasian Geography and Economics 45, no. 3 (2004): 190–211.

This area was called “Shenzhen” into the 1990s, when the government began actively using the term “Dongmen” to distinguish the old market town from the new city, which had moved its offices from Luohu to Futian (formerly known as Shangbu). Dongmen is considered the “heart” of contemporary Shenzhen, while Nantou is treated as a historic site. Mary Ann O’Donnell, “Heart of Shenzhen: The Movement to Preserve Ancient Hubei Village,” in The New Companion to Urban Design, eds. Anastasia Loukaitou-Sideris and Tridib Banerjee (Routledge, 2019), 480–93.

Patrick H. Hase, “Eastern Peace: The Sha Tau Kok Market in 1925,” Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society Hong Kong Branch 33 (1993): 147–202.

“1864-1911 Building KCR,” KCR, https://kcrc.com/en/about-kcrc/history.html (accessed February 9, 2020); Tymon Mellor, “The Kowloon Canton Railway (British Section) Part 4 – The Early Years (1910 to 1940),” The Industrial History of Hong Kong Group, https://industrialhistoryhk.org/kcrc-railway-british-section-3-early-years-1910-1940/ March 10, 2016.

K. W. Chau notes that during the early years of Hong Kong industrialization, water shortages were resolved by rationing water to residents in order to keep factories running, see “Management of Limited Water Resources in Hong Kong,” International Journal of Water Resources Development 9, no. 1 (2011): 68–72. For a more detailed account of cross-border infrastructure, see Mary Ann O’Donnell and Viola WAN Yan, “Shen Kong: Cui Bono?” Border Ecologies: Hong Kong’s Mainland Frontier, ed. Joshua Bolchover and Peter Hasdell (Basel: Birkhauser, 2016), 34–47.

Emma Xin Ma and Adrian Blackwell, “The Political Architecture of the First and Second Lines,” in Learning From Shenzhen: China’s Post-Mao Experiment from Special Zone to Model City, eds. Mary Ann O’Donnell, Winnie Wong, and Jonathan Bach (Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, 2017), 124–37.

“曾是深圳建材来源地 人大代表建议关停上步码头 (This Was Once the Source of Shenzhen Building Materials, Deputies to the People’s Congress on Closing the Shangbu Docks),” Nanfang Dushi (micro-blog), https://sz.house.qq.com/a/20140127/005326_1.htm (January 27, 2014).

Naughton, 109–11.

For more on the history of Shenzhen’s urban villages, see: Carsten Herrmann-Pillath, Guo Man and Feng Xingyuan, Ritual and Economy in Shenzhen: Making the Case for Global Social Science (forthcoming); Juan Du, The Shenzhen Experiment: The Story of China’s Instant City (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2020); Mary Ann O’Donnell, “Laying Seize to the Villages: The Vernacular Geography of Shenzhen,” in O’Donnell et al, 107–23.

Barry Naughton, “The Third Front: Defense Industrialization in the Chinese Interior,” The China Quarterly 115 (September 1988): 351–386.

Jingting Fan and Ben Zou, “Industrialization from Scratch: The Persistent Effects of China’s ‘Third Front’ Movement,” October 20, 2015, SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2676645.

Mel Gurtov, “Swords into Market Shares: China’s Conversion of Military Industry to Civilian Production,” The China Quarterly 134 (1993): 213–41.

Ting Chen, A State Beyond the State: Shenzhen and the Transformation of Urban China (Rotterdam: nai010 publishers, 2017), 151–189.

Silvia Lindtner, “Laboratory of the Precarious: Prototyping Entrepreneurial Living in Shenzhen,” WSQ: Women’s Studies Quarterly 45, no. 3 & 4 (Fall/Winter 2017): 287–305; Silvia Lindtner, Anna Greenspan, and David Li, “Designed in Shenzhen: Shanzhai Manufacturing and Maker Entrepreneurs,” Proceedings of the 5th Decennial ACM SIGCHI Aarhus Conference on “Critical Alternatives,” Aarhus Series on Human Centered Computing, (S.l.), v.1, n.1, (October 2015): 12–25.

Software as Infrastructure is a project by e-flux Architecture as part of “Eyes of the City” at the 2019 Bi-City Biennale of Urbanism\Architecture (Shenzhen).