Take Nebraska Interstate 87 as far as you can North till it becomes South Dakota Interstate 407. Where these two highways meet, you’ll see a tipi on the left-hand side of the two-lane highway standing next to a flagpole. At the top of that flagpole, you’ll see a flag you probably don’t recognize, and below it, you’ll see one you do: the US flag flying upside down. On the right-hand side of the road stands a painted wood sign, which you might recognize as a medicine wheel. It reads “Attention! Per tribal ordinance, 88.01 alcohol is not allowed on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation.” Right past that is a darker wood sign that reads “You are now entering P.O.W. Camp #344 established by the B.I.A. (Bureau of Indian Affairs) March 3rd 1971 A.K.A. Pine Ridge Indian Reservation.”1 Next to it, towers a shiny white metal sign. “South Dakota,” it says, with the bright yellow image of the presidential faces which desecrated the sacred and stolen Black Hills. Welcome to the Oglala Lakota Nation.

Sign at the border between Whiteclay, Nebraska and Pine Ridge, South Dakota. Source: alcoholjustice.org.

The line in the ground separating the land of the Oglala Lakota Nation from the state of Nebraska is a particularly contentious one. From at least the 1940s through 2017, it was marked by alcohol. The Oglala Lakota Nation does not allow alcohol within its reservation boundaries. But, just on the other side of this line sits the unincorporated area of Whiteclay, Nebraska. In 2011 alone, the four liquor stores in Whiteclay sold the equivalent of 4.3 million twelve-ounce cans of beer.2 That would be a rate of 841 cans of beer per Whiteclay resident, per day, if the beer was being sold to the residents. But it wasn’t. Instead, it was being sold to residents of Pine Ridge Indian Reservation, a dry reservation marked by high rates of alcoholism, alcohol-related illness, and alcohol-related deaths.

As defined by Anishinaabe anthropologists Lawrence William Gross, post-apocalypse stress syndrome (PASS) is a culturally-specific form of historical or intergenerational trauma currently experienced, to varying degrees, by all Native Americans. Gross theorizes that all Native Americans have seen the end of their world, lived through the apocalypse, and survived.3 The term describes the “personal trauma, social dysfunction, and crisis in worldview” Native Americans experience as a result of the “imposed cultural destruction” they survived.4 Post-apocalypse stress syndrome is similar to post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), except that the causal trauma, resulting symptoms (alcoholism, substance abuse, interpersonal violence, joblessness, suicide, and more), and ultimate healing all occur at the level of the community, not the individual. Similarly, historians Roy Rosenzweig and David Paul Thelen have demonstrated that Native Americans are the only cultural or racial group in the United States to both explain alcoholism within national history and hold the belief that telling the truth about history will solve community problems such as poverty and alcoholism.5

Mapping Pine Ridge

The territoriality of alcohol has had a key role in defining the boundaries of Indian Country for more than 200 years. In 1802, then-President Thomas Jefferson sought the first overall restriction of alcohol on tribal lands. The United States government then set out to legally define all the areas in which they had just imposed prohibition. The very first attempt to define “Indian Country,” then, was mapped out in territorial boundaries of alcohol and prohibition. These laws continued beyond the passage of the Twenty-First Amendment and the end of prohibition. After Native American veterans returned from World War II, they petitioned for their right to drink. In 1953 Native Americans were finally given the right to be served alcohol anywhere in the US, and reservations were allowed to determine if they would like to allow alcohol on their land or not. About two-thirds of reservations currently allow alcohol. Pine Ridge Indian Reservation does not.

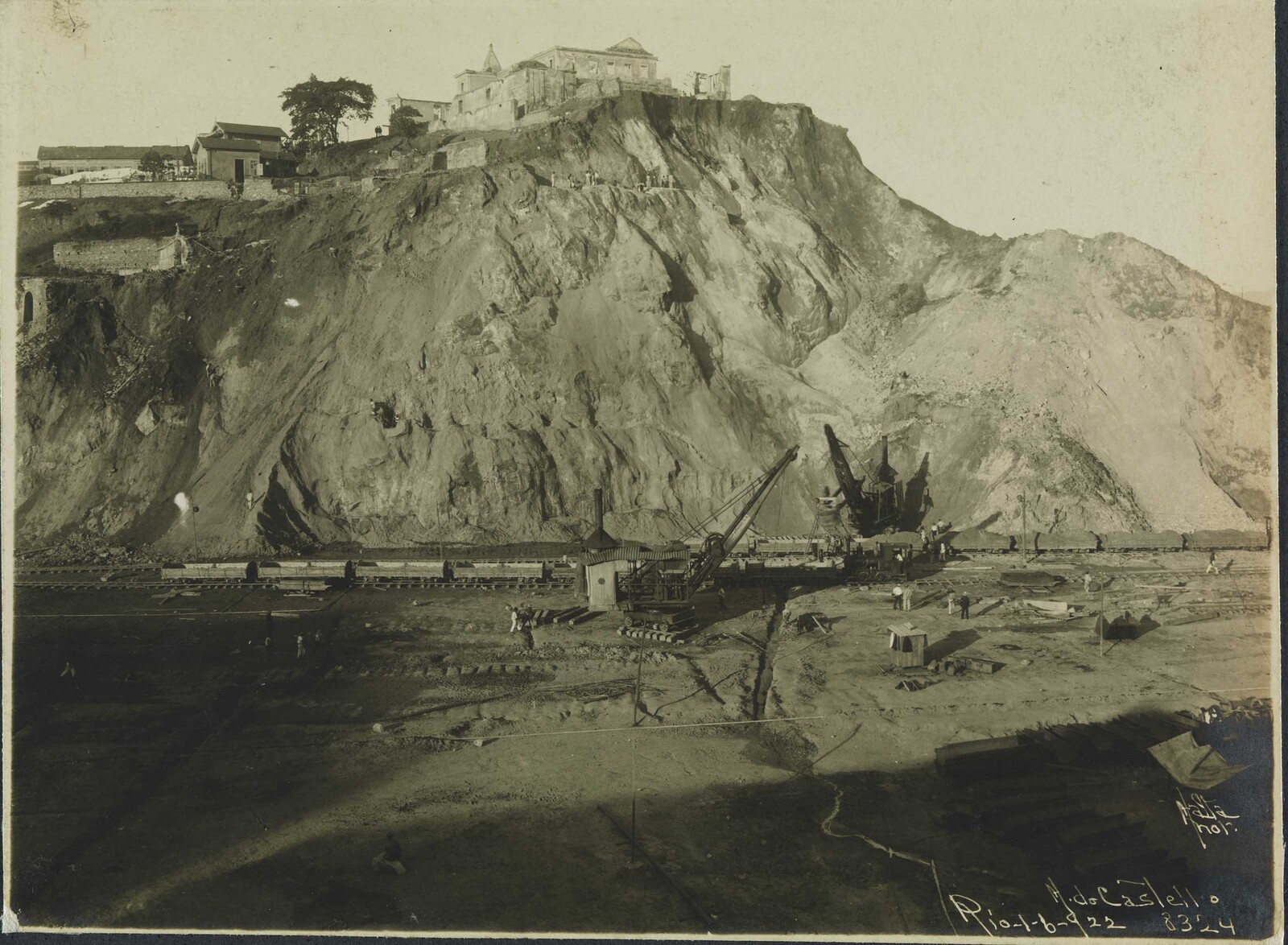

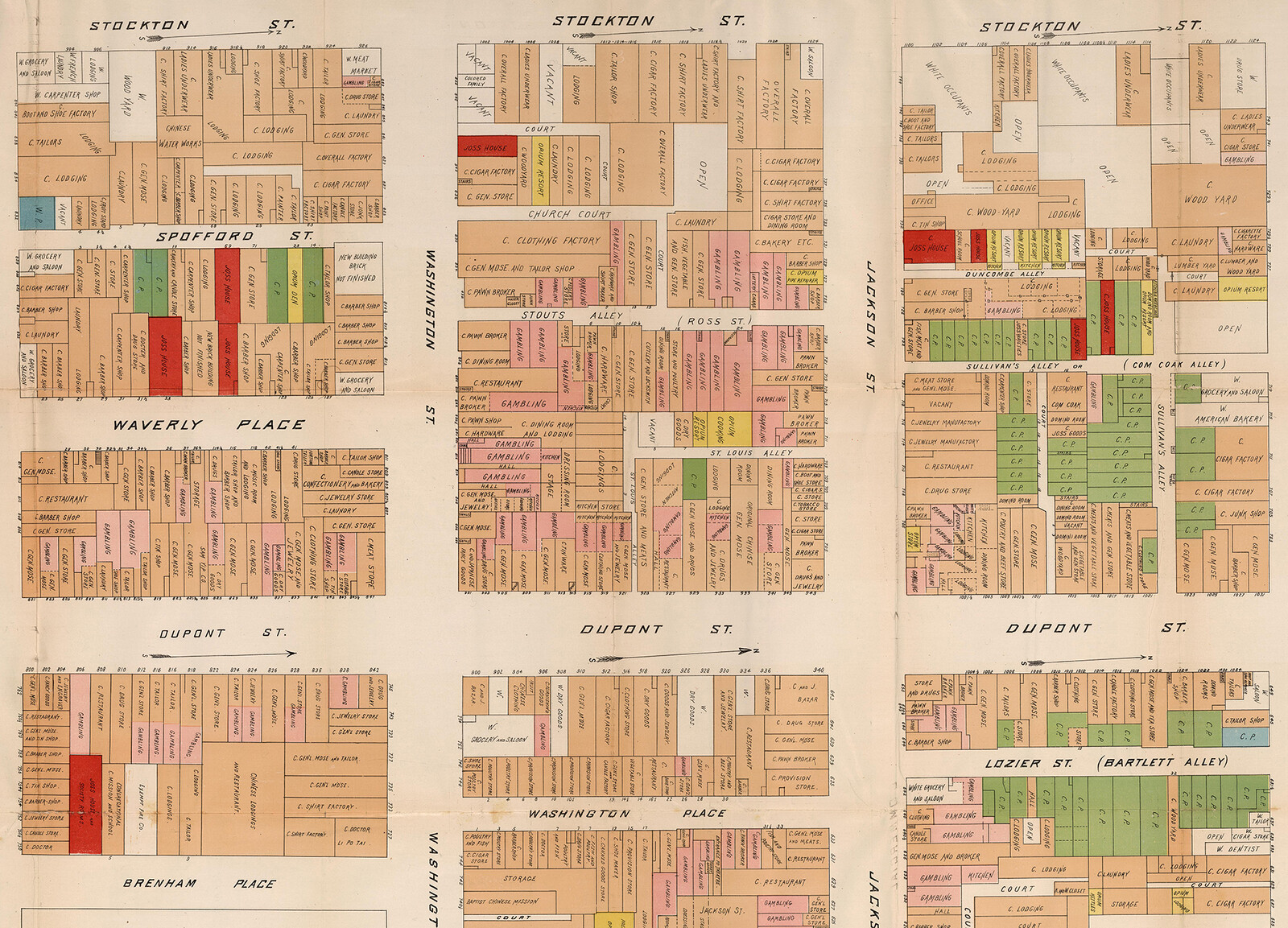

The first time Pine Ridge appears on a map as a reservation or sectioned-off territory is in report Senate No. 352 from the Committee on Military Affairs printed on March 10, 1892. “Map Showing the Position of Nebraska State Troops in Indian Campaigns of the Winter of 1890-91” depicts reservation boundaries along with the settlement patterns of the Oglala Lakota, the Nebraska National Guard, and the United States Troops.6 At the top of the map within the reservation boundary, an Oglala Lakota settlement is marked with small X’s and labeled “Hostile Indians.” A photograph from the times shows this settlement from a distance, overlooking White Clay Creek. US Troops are also settled within the reservation along White Clay Creek and Wolf Creek, represented by detailed canonical tent structures almost three times the size of the X’s meant to depict tipis. Yet photographs of the two settlements look more similar than different. At this moment in time, the situation for the Oglala Lakota and the US Department of War was exceedingly similar.

Below these settlements is a rectangular sectioned-off portion of land labeled “Friendly Indian Reservation in Nebraska” which meets Pine Ridge Indian Reservation at the South Dakota/Nebraska border. The upper portion of this reservation is covered in the same X’s that marked the tipi settlements of the “Hostile Indians.” While the reservations’ borders are straight and definite, the “Friendly” Oglala Lakota settlement appears to spill over the marked boundary without disruption, coming all the way up to the creeks to directly below Pine Ridge Agency.

The land then labeled as a “Friendly Indian Reservation in Nebraska” continued to reappear under various guises to serve the same purpose; to pacify Oglala Lakota people as they were moved along through the United States mission of Oglala Lakota extermination, while also protecting and increasing white settlers access to wealth. After the end of the “Indian Campaigns” it was held by the US government as a buffer zone, where neither white settlers nor Oglala Lakota were allowed, with the official purpose of protecting people and property. In 1904, President Theodore Roosevelt stated the buffer zone to be unnecessary and, without consulting with the tribe, reduced the buffer to a one-square-mile zone on the South Dakota-Nebraska state border. Settlers quickly rushed in and formed what is now the unincorporated area of Whiteclay, Nebraska. Nebraska Interstate 87, which ends in Whiteclay right outside of the reduced buffer zone, was completed in 1935, and the first photographs of bars and taverns appeared in 1940. From at least then on out, Whiteclay has served alcohol to Oglala Lakota people.

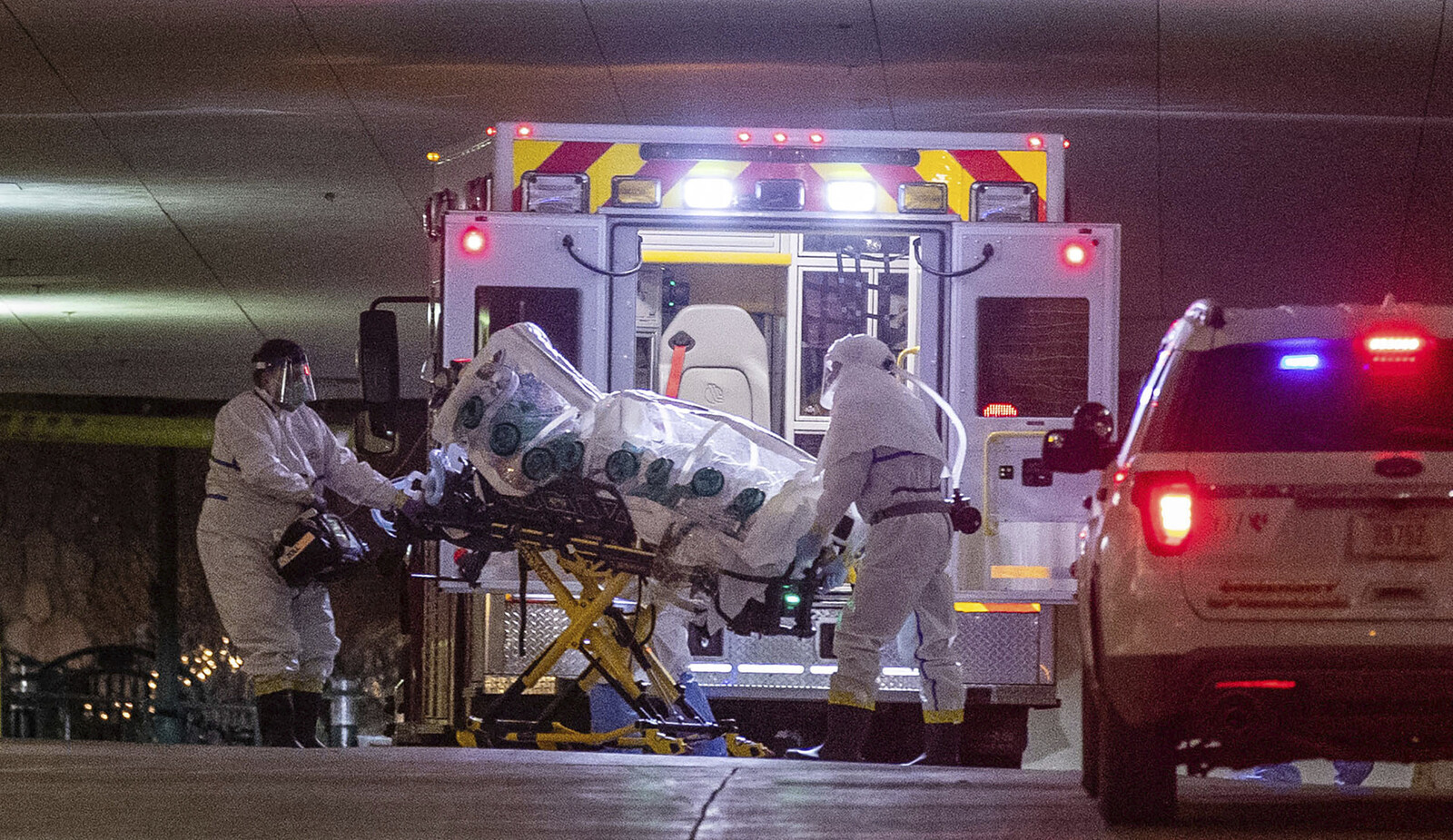

The territoriality of alcohol in Whiteclay, Nebraska has functioned as a mechanism to keep the Oglala Lakota people in an unending and intergenerational camp; a camp that can be seen and defined in the bodies of the people; a camp that flowed without resistance across the state line, just like the little X’s did back in 1890 and 1891.7 The architecture of Whiteclay appears quite innocuous: a few buildings on the side of the road, just like they are in so many other places in the country. But bare life and Oglala Lakota death dominate the landscape. Buildings are scarred with artifacts of Oglala Lakota pain. While Whiteclay isn’t officially extraterritorial in the way that the reservation is, until recently Nebraska did not enforce its own laws or provide police presence, and the Oglala Lakota were not legally able to enforce their laws on land outside of their sovereign jurisdiction. There are no fences with barbed wire keeping the Oglala Lakota there. There are no police, troops, or armed militia forcing people to drink. The reports coming out of the Indian Health Services (IHS) hospital on the reservation are grim, but there are no gallows for hangings, “death walls” for firing squads, or gas chambers for mass executions. Instead, it’s the everyday architecture and continual disregard that perpetuates the “inevitable” elimination of the Oglala Lakota. The infrastructure of the camp is the absence of police, the dogma of free-market capitalism, and post-apocalypse stress syndrome.

I could go on but I won’t. The land that was the “Friendly Indian Reservation in Nebraska” continues to do what it was designed to do back in 1890 and 1891. In 1890 it didn’t matter to the US Troops that the Lakota resistance and theft that supposedly necessitated the military intervention was a direct result of the US policy of killing all the buffalo. In the same way, the off-reservation liquor stores marked by Lakota dependency and death are the Oglala Lakotas’ own fault. It doesn’t matter that they’ve lived through the apocalypse and survived. And it’s absolutely not even worth thinking about who ended their world in the first place.

The date on the sign corresponds with the passage of the Indian Appropriations Act of March 3, 1971 which stated that Tribal Nations would not be recognized “as an independent nation, tribe, or power with whom the United States may contract by treaty.”

Timothy Williams, “Indian Beer Bill Stalls; Industry Money Flows,” The New York Times, April 11, 2012, ➝.

Lawrence William Gross, Anishinaabe Ways of Knowing and Being (England: Ashgate Publishing Limited, 2014), 33.

Gross, 33.

White Americans, in contrast, explain alcoholism through personal and family histories. Roy Rosenzweig and David P. Thelen, The Presence of the Past: Popular Uses of History in American Life (New York: Columbia University Press, 1998), 173.

The map labels the Nebraska National Guard as the “Nebraska State Troops.”

I draw the term “camp” from the community’s own use of the label “P.O.W. Camp #344” in reference to the reservation. While my use of the term “camp” is informed by Giorgio Agamben’s, Agamben did not, and likely would not, recognize Pine Ridge Indian Reservation as a “camp.” For more on this, see Mark Rifkin, “Indigenizing Agamben: Rethinking Sovereignty in Light of the ‘Peculiar’ Status of Native Peoples,” Cultural Critique 73 (2009): 88–124.

Sick Architecture is a collaboration between Beatriz Colomina, e-flux Architecture, CIVA Brussels, and the Princeton University Ph.D. Program in the History and Theory of Architecture, with the support of the Rapid Response David A. Gardner ’69 Magic Grant from the Humanities Council and the Program in Media and Modernity at Princeton University.