A Highly Controlled Visibility

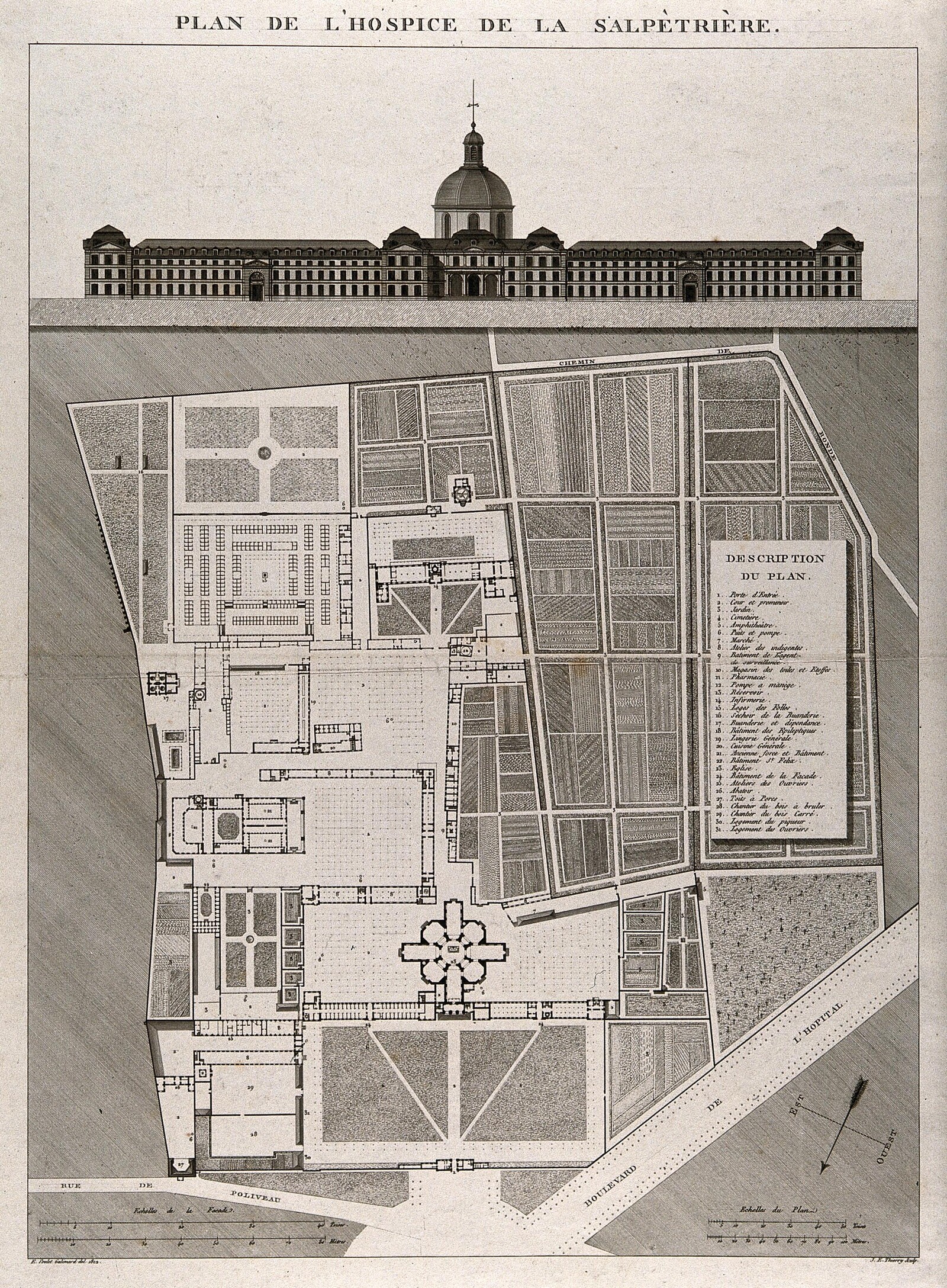

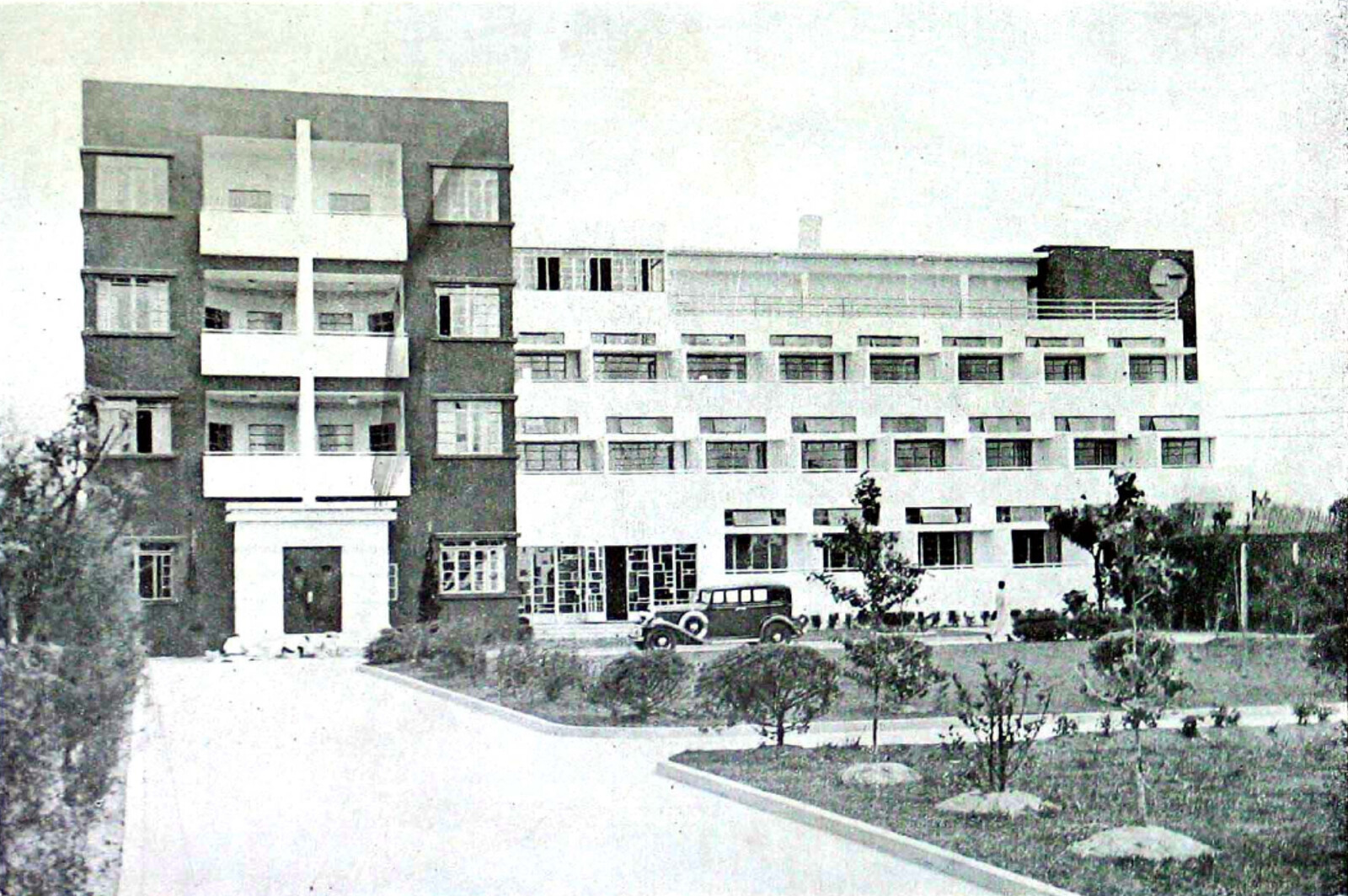

Up until 1968, L’Hôpital de la Pitié-Salpêtrière in Paris treated women exclusively. During the time that Doctor Jean Martin Charcot famously endeavored to visually typify hysteria, between 1872 and 1892, the medical architectural complex comprised forty-five buildings and approximately five thousand women inmates.1 Founded by King Louis XIV in 1656 as an institution for the confinement—and concealment—the history of its buildings amplifies the horror associated with the stigma of its inmates. La Salpêtrière was originally built on the site of an arsenal of explosives, the Salpêtre, and during the French Revolution, it became the setting for an infamous massacre of destitute women,2 an event which indelibly tainted the reputation of its walls as enclosing a “feminine inferno.”3

During the times of Charcot, women would be confined to La Salpêtrière “voluntarily” or “par office.” The denomination of the former, however, is misleading, for women would be often institutionalized not by their own will but by request of a member of their families, who disproportionately tended to be men— husband, brother, son. Women were judged detainable in terms of their “dangerosity,” a conveniently flexible legal criteria open to the interpretation of the accuser, the judge, and the discriminating medical physician.4 Women targeted by the police included those judged as undesirable and marginal: vagabondes, idiotes, imbéciles, personnes agés; women who profited from or asserted their sexuality: prostitutes, “seductresses,” débauchés, and érotomanes; as well as those considered aggressive: women who swore, yelled, or could otherwise be considered indomitable (insoumises, agitées, indisciplinées). Women would enter as medical patients, but often become “filles de salle,” that is, permanent residents at the hospital from which they would never be released.5

La Salpêtrière existed as a permanent threat for women inclined to what society dictated as undesirable behaviors. At the time, the display of female subjectivity in the private, public, or political domains was deemed not only transgressive, but pathological, and therefore to be repressed and treated. Displays of transgressive femininity were perceived as menacing and could only be permitted at the margins, made invisible, or shown in a highly controlled light. The walls of La Salpêtrière defined a place of stigma, enclosing “undesired differentness,” and operated as a social mechanism destined to identify and visibly exclude such difference.

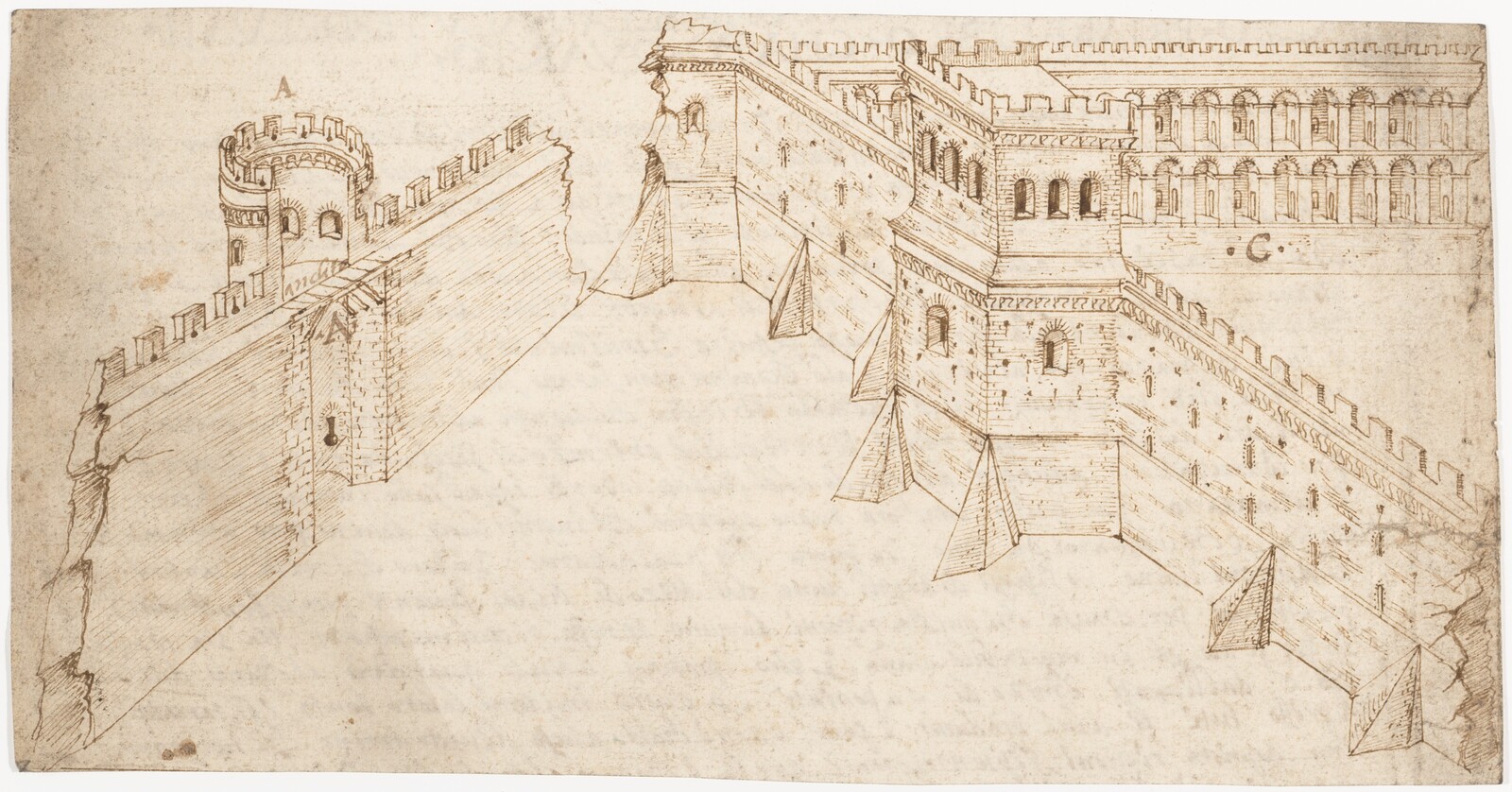

Architecture staged hysteria at La Salpêtrière, both its exclusion and its spectacularization. Visual barriers blocked the view from the city towards the inside of the hospital. A system of successive walls constructed the enclosure and built-up the seclusion of its female inmates. Its symmetrical wings acted like framing devices around a central opening, which in turn is immediately blocked by the Chapelle Saint Louis. Beyond the prominent volume of the Chapel, the sightline of an outsider is tunneled through an old prison and surveillance pavilion. Relays of walls perpendicular to the observer’s point of view further restricted their line of sight towards the patient’s wards, hidden at the back of the complex. These, in turn, are flanked by gardens, serving as visual and potentially acoustic buffers that adorn and distract from a presumably terrifying sight, or at least a nuisance for city dwellers deemed sane.

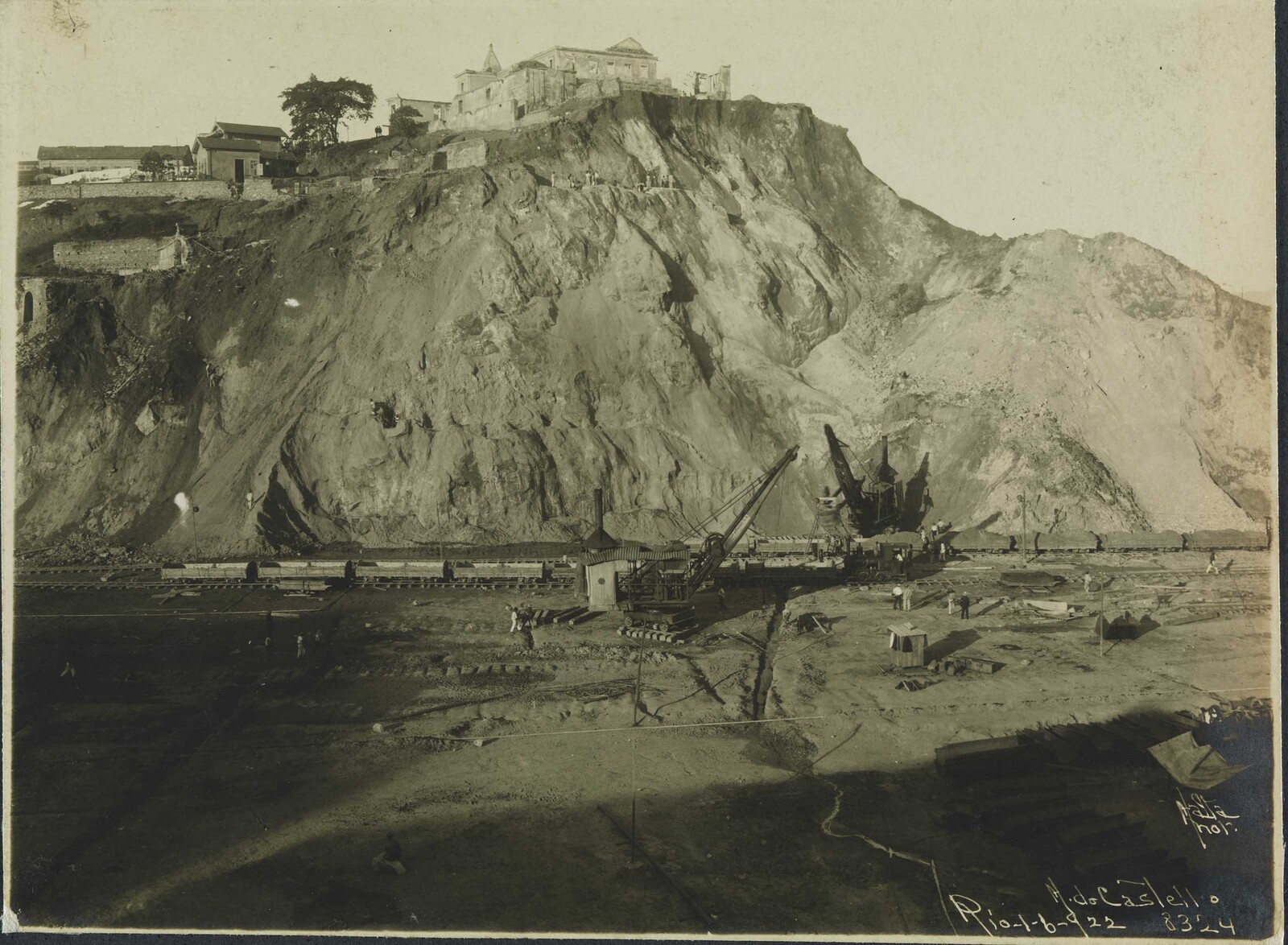

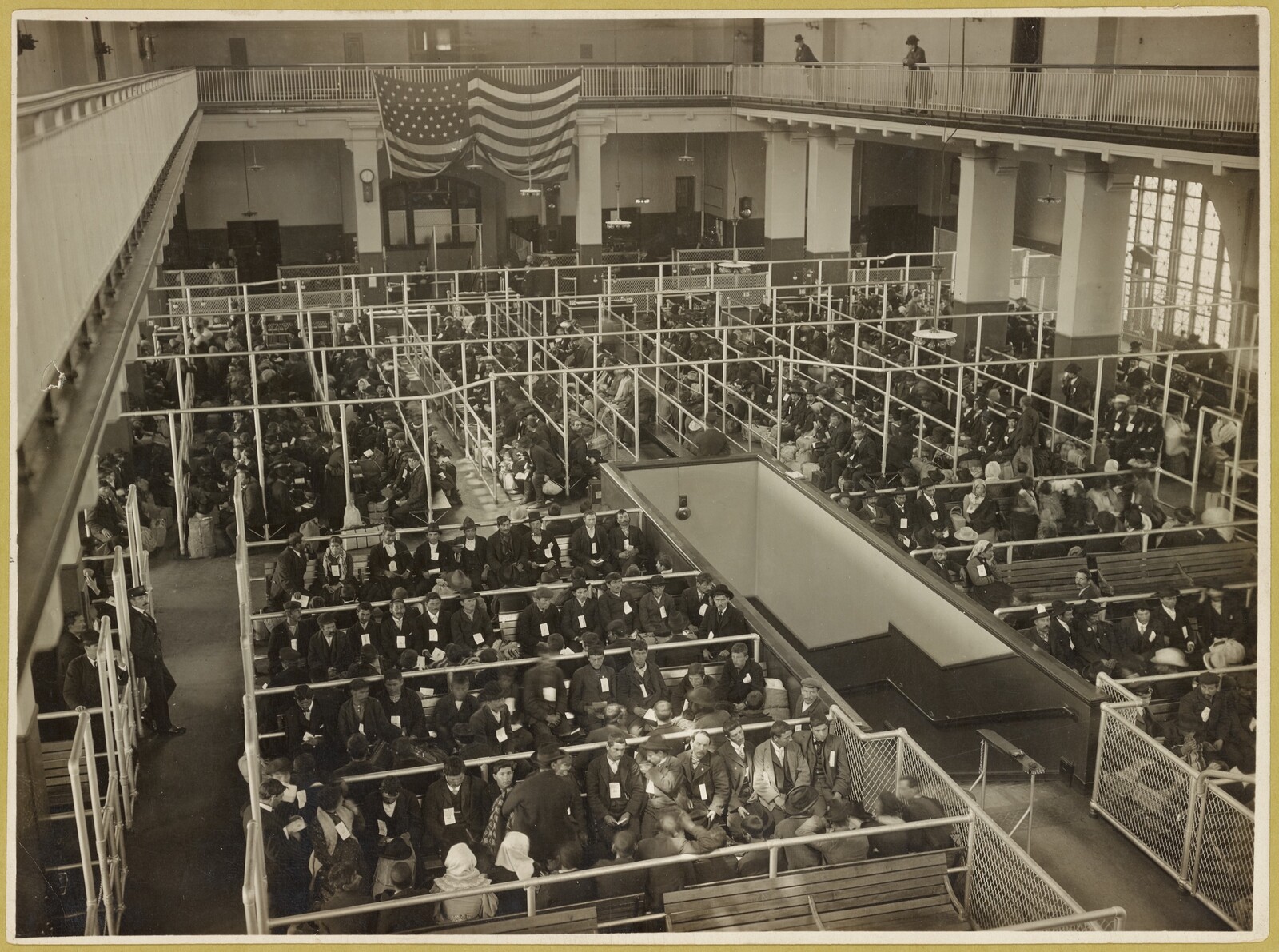

While what happened inside its walls remained largely concealed from the public the detainment of inmates was highly public and publicized. The transport of new inmates to La Salpêtrière had historically been purposefully designed as a procession of shame. The architectural concealment achieved at the urban scale, continued to be reproduced at the scale of interior furnishings of the patients quarters, with “several dozen beds lined up, some closed by curtains, hiding the “relaxing,”often incurable, bedridden.”6 The madwomen quarters have paradoxically and tellingly been referred to as “display pavilions.”7

Etienne Jeurat, La Conduite des filles de joie à la Salpêtrière: le passage près de la porte Saint-Bernard, 1757.

Visibility as Occlusion

From as early as 1835, a yearly public event was organized by l’Assistance Publique and hosted at La Salpêtrière, the so-called Bal des Folles (The Ball of The Crazy/Mad), as part of the Carnival of Paris.8 An audience of outside guests and the public at large would be invited to spend an evening dancing to orchestral music alongside the women interned at La Salpêtrière. Called upon to perform their illness, the event was considered therapeutic treatment for the inmates and a “joyous entertainment” for the Parisian public at large.9 Inviting guests including journalists, which Charcot himself selected, to traverse the precinct of La Salpetrière was an opportunity for its director, doctor Jean Martin Charcot, to display the claimed modernity of his experimental methods.

Le Bal des Folles à l´Hôpital de la Salpetrière. From “L’ Univers illustré”, Paris, March 17, 1888.

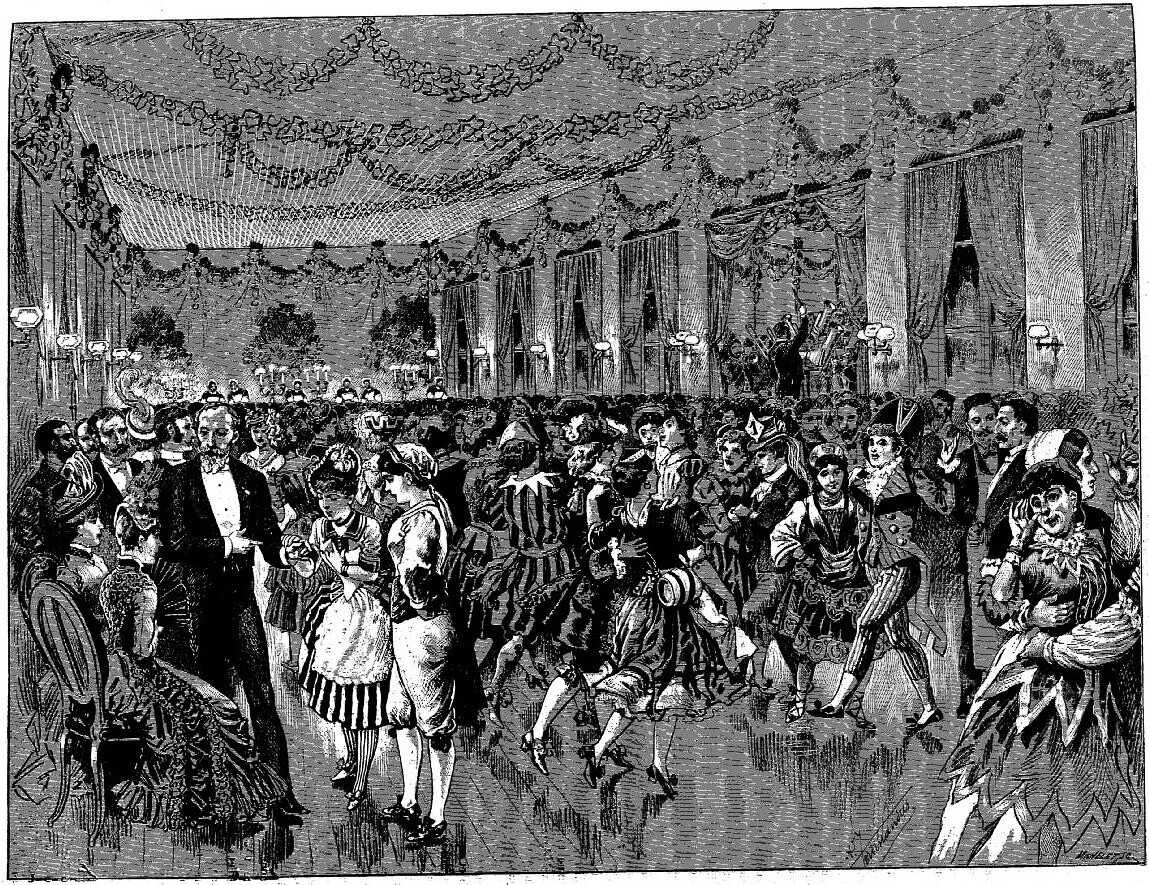

Le Bal was a public showcase of the theatricalization of madness. According to Maxime Du Camp, a journalist who reported on le Bal of 1893, “the [hysteric] woman … exaggerates her role, speaks, gesticulates, tells and initiates, at first sight, to all the mysteries of her aberration.”10 But what if the inmates welcomed the opportunity offered by these events to partake in society and to be seen as women, individuals, even if the pathological judgment of women’s behavior was ultimately not lifted? In the words of a reporter who attended le Bal of 1884: “What do you want, women remain women everywhere and always, at the Salpêtrière as elsewhere.”11

Other than the desire to please, and to be applauded by the same society who had marginalized, judged, incriminated, excluded, and incarcerated them, they were given the pleasure of performance, as well as, and perhaps most importantly, the pleasure of asserting themselves and their desires.12 The hysteric woman embodied her desire by performing herself, or the woman she wished she could be, in the form of “hyperbolic incarnation.”13 Thus, through the “considerable magnification” of pathos, the symptomatology of the hysteric became akin to the art of the histrionic.14

Jane Avril, dancer of the Moulin Rouge (and patient at La Salpêtrière). Photograph by Paul Sescau, circa 1890.

Inmates would spend months anticipating the festivity and preparing their costumes (“the most varied, the most picturesque, the freshest”).15 In his recount of le Bal of 1889, the psychiatric doctor and invitee Dr. Frédet noted that the hysteric women presented themselves in such a manner that “one would believe to be within one of the most elegant societies.”16 Conversely he pointed out that it was the guests, rather than the hosts, who “were the less tranquile, who made the most noise, who were the most agitated, and those who, an impartial spectator would think at first sight, are the inhabitants of the house.”17 Not only did the occasion facilitate the exceptional reversal of order and societal values allowed by the days of carnival, but may have provided the rehearsal and showcase of new attitudes and modes of behaving to be more permanently adopted: “The imitation of reason for the mad, and the imitation of madness for the guests” rendered hysteria potentially contagious beyond the psychiatric walls.18

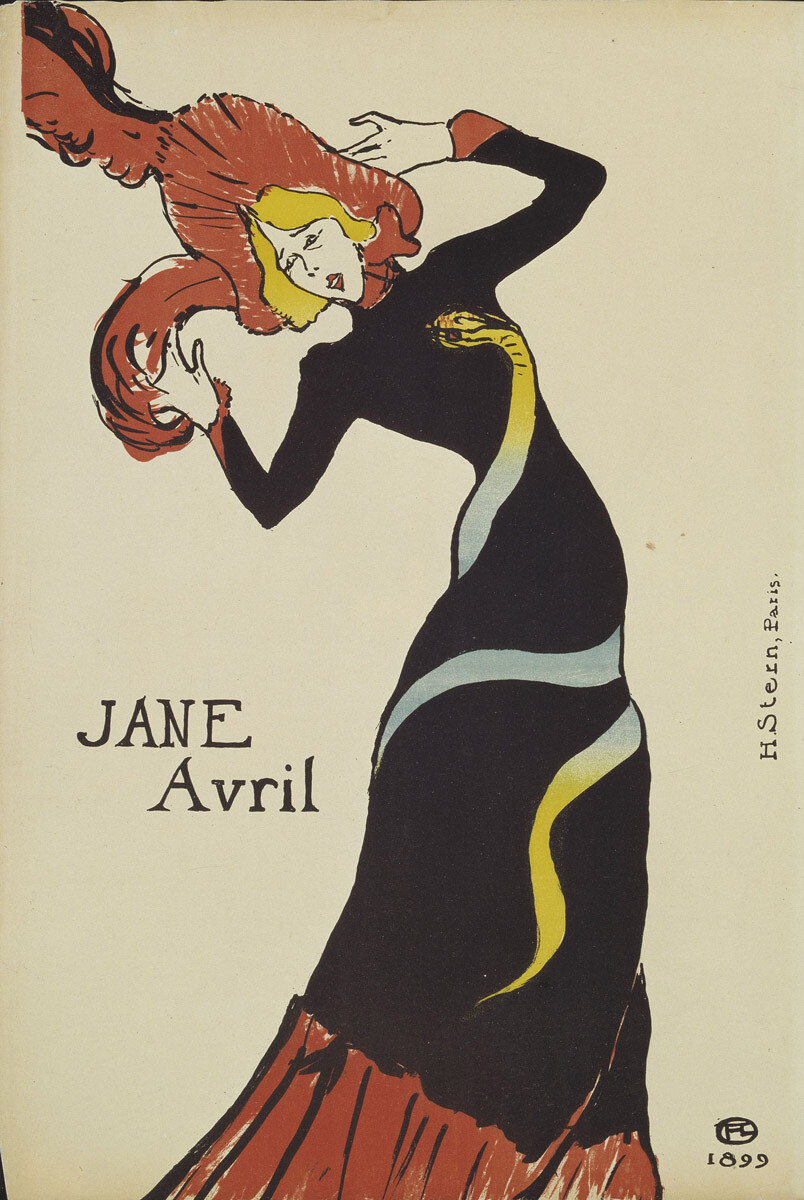

Henri de Toulouse Lautrec, Jane Avril, 1899.

The Clinical Stage

Other than the yearly Bal, Charcot hosted his famous weekly “Tuesday Lessons,” which became well attended events by a large spectrum of Parisian society including Sigmund Freud, the brothers Goncourt, Guy de Maupassant, Octave Mirbeau, Alphonse Daudet, Jane Avril, Rachel, and Sarah Bernhardt.19 During these events, Charcot would publicly perform a real-time consultation and diagnosis of new incoming patients.20 The leçons were highly produced multimedia events which included the use of printed photographs, photographic projections, drawings quickly executed in chalk, live hysteric bodies performing movement and speech, mimes enacted by Charcot himself, picturesque narratives, dramatic interrogations, and more. The repertory scenes of hysteria Charcot offered to his audience were scripted in real time, directed live, and supertitled. He would enunciate descriptions that would serve at once as stage directions for the women, and as a synopsis guiding the audience in the unfolding of the hysteric plot. “The patient who has just been placed under your eyes is…”21

Maurice Biais, Jane Avril, 1895. Printer: Imp. Charles Verneau, Paris.

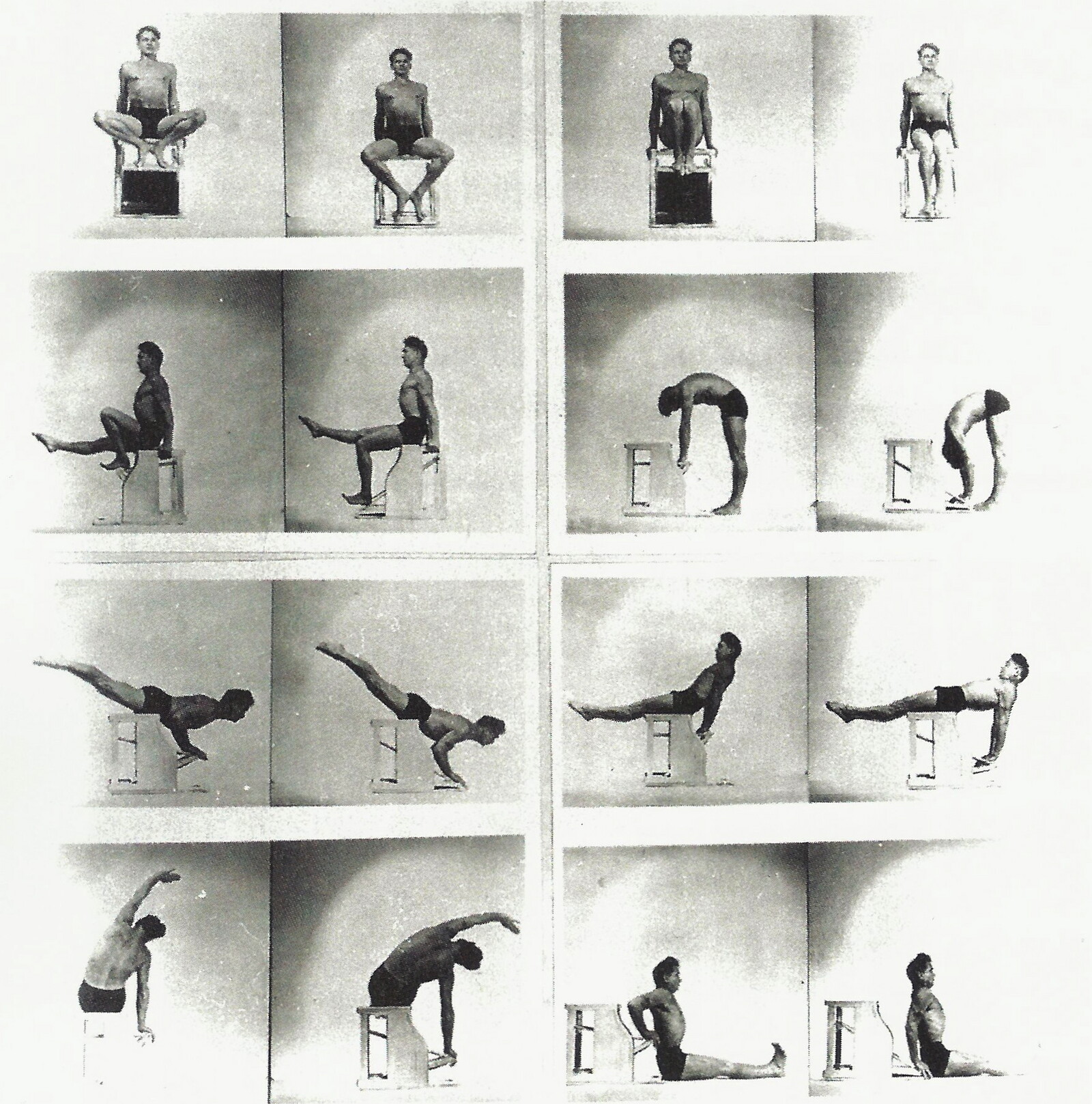

Charcot performed simultaneously the role of the medical authority, the host master of ceremonies of the show, and the omniscient live narrator, and the voiceover—the voice of scientific objectivity. The “leading ladies of hysteria”—Louise Glaiz, Alphonsine Bar, Blanche Wittman—would strike poses, articulate gestures, and enact didascalies to compose the unfolding image of hysteria the physician was trying to recreate.22 Charcot used their bodies to direct an indexical form of hysteria, as visually described in the manuals of neurology he himself produced to typify hysteria. Re-enacting a constructed archetype, women became effigies of the illness they were set to portray and embody. The women’s diligence in following directions was such that they were compared to “puppets,” “mannequins,” and “automata.”23

Sarah Bernhardt c. 1880. Photo: Sarony.

During the Lessons, women were manipulated and penetrated with medical props.24 Allegedly, the hysteric woman would relentlessly recreate the symptoms that could only be alleviated, through transference, by degrees of sexual interaction or outright intercourse with the medical doctor or intern most readily available, which she would herself vocally solicit. Reciprocally, the physician would be enamored by the living proof of his scientific research: she who would guarantee his professional success, consent to enact his medical fantasies word by word, and provide sexual satisfaction.25 The almost compulsive acting-out of roles by the women must have proven highly erotic to the audience.26

The Emergence of a New Femininity

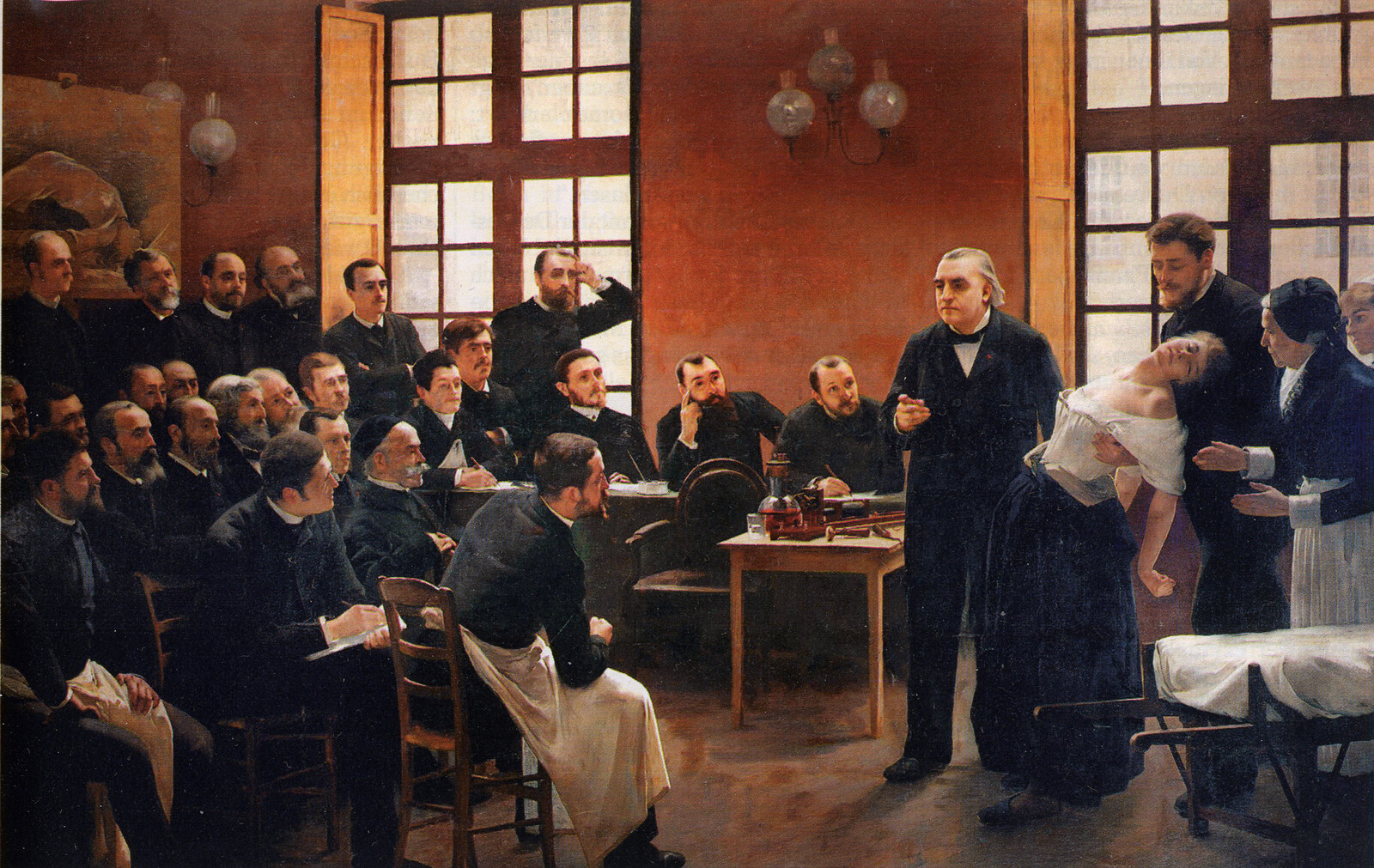

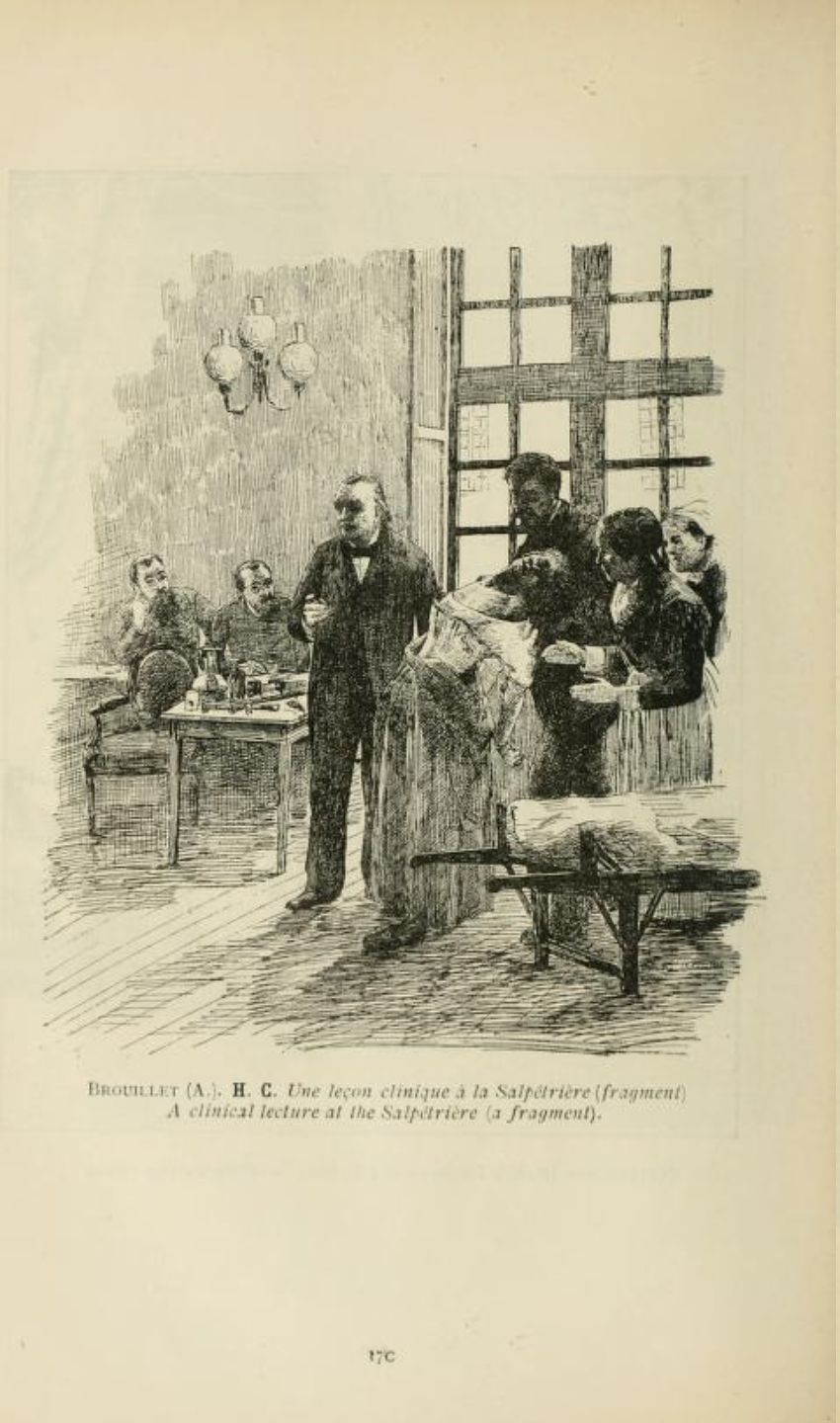

The amphitheater in which the famous Tuesday Lessons took place no longer exists, and no photographic documentation survives of Charcot’s public demonstrations of hysteria. However, the painting Une Leçon de Clinique à la Salpêtrière (1887) by André Brouillet has filled the collective imagination with spatial evidence of these events. The tableau presents a central male figure, standing, dressed in a black suit, white shirt, a black bowtie, his finger pointing towards the viewer. The gesture may be one of instruction, or direction, but also a silent warning for the viewer of the painting. The twenty-four other men gathered around him are dressed alike, and pay close attention to him. Most of them are sitting on wooden ladder-back chairs, others at the back of the room are standing. Some of them seem perplexed while others take notes. All await the following words to be uttered.

At the center of the painting is an armchair with leather upholstery next to a simple table exhibiting medical props. The leading lady of the scene is in arc-en-cercle—an iconic posture associated with a woman performing hysteria, which is also popularly considered, to this day, a highly erotic posture—and is being held from behind by a man whose gaze is focused on her neck. Her costume consists of a white off-the shoulder blouse with a revealing décolleté; her corset seems to be untightened. She might be in the process of being unclothed, before the eyes of all attendees, for the upper part of her dress has been unbuttoned and hangs down her waist. The lighting of the scene makes her chest the focal point, where the eyes of most of the depicted men and the eyes of the viewer are directed to converge. The brightest whites in the picture take the viewer’s eye from her body to the adjoining bedsheets, untidy on the stretcher, one of the few other props on stage. On the back wall, two large windows allow daylight to come in, but screen the view towards the outside.

The colors of the set are warm, while the gaze of the men is not: they seem interested, but not concerned; certainly not worried or alarmed. The scene is routine and repetitive for them. Another attendant, an older woman, highly covered in her attire, extends her hands toward the fainting woman, as if anticipating the next scene. Her skirt is white, pleated, and clean, while two of the seated men downstairs wear dirty aprons. A third woman’s face barely makes it into the frame. Suspended on the left wall is a chalk drawing of a woman in arc-en-cercle; arching her back on a bed, her left breast again highlighted, her clothing thin enough that it allows her figure to be seen through.

The group portrait of the ensemble whose performance defined modern hysteria, was first shown as art at the Paris Salon of May 1887.27 Charcot himself kept a reproduction of Brouillet’s painting in his living room all of his life, and Freud displayed one in both his Vienna and London medical studios. The original painting is now exhibited at the Paris Descartes University, near the entrance of the Museum of Medical History. The variation of institutional contexts of the painting’s display mirrors the ambiguous position of Charcot’s lessons between the realm of art and representation, and that of modern science.

Page 170 from the Catalogue illustré du Salon de Paris (1887).

In an article written for L’Événement in 1885, Octave Mirbeau describes Charcot’s amphitheater. He writes of a long hall half occupied by rows of seating, a space where all windows were “hermetically closed and obstructed” and where no daylight could “pierce through the obscured light produced by the gas lamps.”28 He reports empty seats due to an avid audience gathered around the “professor,” the patients and the medical aids. He describes two small tables with a “few electrical instruments, demonstration boards and a large chalkboard.” He ends his article with the words “Voilá la mise en scène” (“This is the staging”).29

The women of La Salpêtrière redefined femininity in the public eye. They were displayed on Charcot’s stages— the architectural complex of La Salpêtrière itself, the yearly showcase of Le Bal held within its premises, and the weekly public lessons in its amphitheater— mediatized by photography in Charcot’s compendia of neurology, and popularized and catapulted to fame by word of mouth. Charcot’s media-machine inadvertently advanced the plight of women by amplifying and distributing their image as an overtly sexual subject whose sexuality was transgressive of all pre-established limits of normalcy. Indeed, there were other women in the audience— both those directly witnessing the medical performances and those who accessed it through the media and culture of fame—who might have felt liberated seeing these images.

The spectacle of hysteria was a sublimation of the collective oppression of women, and took shape in the form of a scandalous, shockingly visual manifestation of rebellion. In a hysteric attack, the patient performs a highly active and visible dispossession of her inhibited self; a body violently reclaiming its sexuality, unapologetically exhibiting its desire and assertively enacting its satisfaction in public. The effect on (oppressed) women who witnessed other (allegedly ill) women reclaiming their subjectivity and their right to sexual expression must have been inspiring, and seemingly contagious.

Charcot himself played with the fact that hysteria was perceived as highly transmissible, and would address his audience with the following warning: “look at it [hysteria] and try not to be influenced, suggested, or intoxicated by what you will see and hear.”30 His warning may have also worked as a threat, a demonstration of what could happen to any woman who behaved deviantly. But women joining the ranks of hysteria might have proven that they were better off confined than outside the psychiatric wards. The expansive character of hysteria earned it to be considered “the epidemic of the fin de siècle” and a public health concern, while the term “collective hysteria” has come to signify the susceptibility of the masses to suggestion.31 Hysteria, then, took place, collectively, as an event, and advanced the cause of another, subsequent, epidemic in gestation: a femininity publicly assertive of its sexuality.

Charcot was a médecin des hôpitaux de Paris and headed a department at the Salpêtrière in 1862; he became a professor of pathology at the Faculty of Medicine of Paris in 1872; and the chair of a department of the diseases of the nervous system created for him at La Salpêtrière in 1882. Emmanuel Broussolle, Jacques Poirier, François Clarac, and Jean-Gaël Barbara, “Figures and Institutions of the Neurological Sciences in Paris from 1800 to 1950. Part IV: Psychiatry and Psychology,” Revue Neurologique 168, no. 4 (2012): 301–320.

In 1656, Louis XIV signed an edict establishing an institution named “l’Hôpital Général pour le Renfermement des Pauvres de Paris,” General Hospital for the Confinement of the Poor. This newly founded institution was to intern the poor, destitute, homeless and other forms of socially marginal persons, for they were considered to disturb the social order of Paris and stain its image. The Pitié was established for the children, Bicêtre was the hospice for men, and la Salpetrière for women and girls. The location of the old arsenal, sited in what was then the outskirts of Paris, because explosives could not be stored within the city limits without considerable risk, was conveniently out of sight. “Le 3 septembre 1792 des hommes ivres du Sang versé dans toutes les Prisons de Paris, allèrent à l’Hôpital de la Salpêtrière, se firent représenter les prisonnières au nombre de quarante-cinq et … les assommèrent sur le place, la femme Desrues fut une des premières victimes.” (“On September 3, 1792, men drunk on blood spilled in all the prisons of Paris, went to the Salpêtrière Hospital, asked to be presented with the forty-five (female) prisoners and … knocked them out in place, the Desrues woman was one of the first victims.”) Translation mine. Inscription on the back of “Massacre of Prostitutes at the Salpêtrière Hospital on September 3, 1792, current 13th arrondissement.” Journal des Révolutions de Paris, September 1-8, 1792.

Expression employed in Georges Didi-Huberman and J. M. Charcot. Invention of Hysteria: Charcot and the Photographic Iconography of the Salpêtrière (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2003), xi.

Guy de Maupassant, “Une femme,” Gil Blas, August 16th, 1882. “Vous êtes ceci, vous êtes cela, vous êtes enfin ce que sont toutes les femmes depuis le commencement du temps. Hystérique!” (“You are this, you are that, you are at last what all women are from the beginning of time. Hysteric!”)

Olivier Walusinski, “The Girls of La Salpêtriere,” Frontiers of Neurology and Neuroscience, Hysteria: The Rise of an Enigma 35 (2014).

At the time of the founding of La Salpêtriere, madwomen were treated as beasts. They were chained, often naked, and lived in underground quarters, behind bars. Their daily provisions consisted of bread and water, and they slept on a floor covered with straw which would be changed monthly. It was not until 1792, when Dr. Pinel revolutionized the status of madness by claiming “the mad are ill”, that they started being considered patients, unchained, and offered treatment. But even from then on, there was only one bed per six inmates: two women would sleep on the floor until they were relayed by scheduled rotation. Le Bal Des Folles, Une Grande Fête à la Salpêtriere, Le Matin Derniers Télégrammes de la Nuit, March 21, 1884.

Termed “Pavillion Vitrine” by Yann Diener, psychoanalyst, in an interview for France Culture, February 15, 2020.

Julie Froudière, “Littérature et Aliénisme: Poétique Romanesque de l’Asile (1870-1914),” Université Nancy (2010), 138. Michel Caire, “Le Bal des Folles de la Salpêtriére,” interview for France Culture.

Idem: “un joyeux divertissement pour le public parisien.”

Maxime Du Camp, Paris, ses organes, ses fonctions et sa vie dans la seconde moitié du XIXème siècle 6 (Paris: Hachette, 1893–1894).

“But this… ball is like a break, a pause for all those victims of the great disease of the century, neurosis, for all those heads devoid of reason or peopled with incoherent thoughts, called the crazy. The ball is everything, a fortnight before and fifteen days after… More than one agitated madwoman calms down. More than one atrophied or softened brain seems to regain a flash of thought. What do you want, women remain women everywhere and always, at the Salpêtrière as elsewhere. You have to look pretty for the ball.” Le Bal Des Folles, Une Grande Fête à la Salpêtriere, Le Matin Derniers Télégrammes de la Nuit, March 21,1884.

“Les aliénées se donnent en spectacle dans une aliénation que le costume travestit, rendant floues les barrières entre le monde de la folie et de la raison. (“The alienées offer themselves as spectacle in an alienation that the costume travestis, blurring the boundaries between madness and reason”.) Yannick Ripa, La ronde des folles: femme, folie et enfermement au XIXe siècle, 1838-1870 (Paris: Aubier, 1986), 135–136.

Charles Féré, “Sensation and Mouvement,” Revue Philosophique 20 (1885): 337–368. Cited in Bertrand Marquer, Les Romans de la Salpêtrière: Réception d’une Scénographie Clinique: Jean-Martin Charcot dans l’Imaginaire fin-de-siècle (Genève: Droz, 2008), 130.

Charcot explained “it is a characteristic of hysterical patients to exaggerate their phenomena and they are more prone to do so when observed or admired,” Christopher G. Goetz et al., Charcot: Constructing Neurology (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1995), 173. “There were crazy girls, whose disease, called ‘hysteria,’ consisted above all in simulating it.” “Il y avait ces folles filles, don la maladie, denominéee “hysterie”, consistait surtout à la simuler.” Avril Jane, Mes Mémoires (Paris: Phébus, 2005), 437.

Docteur Frédet, “Un bal à la Salpêtrière,” Mélanges nouvelles historiques et scientifiques, Bulletin historique et scientifique de l’Auvergne (1889). Cited in Froudiére, 142.

Docteur Frédet, cited in Froudiere, 142: “Il y a là environ cent cinquante femmes, jeunes pour la plupart et dont quelques-unes sont fort belles, qui se promènent, en attendant l’appel de l’orchestre, revêtues des costumes les plus variés, les plus pittoresques, les plus frais, et dont quelques-uns, je dois le dire, sont portés avec une crânerie, une aisance tout aristocratique. On se croirait vraiment dans le monde et dans une société des plus élégantes.” (“There are about a hundred and fifty women there, young for the most part and some of whom are very beautiful, who walk around, waiting for the call of the orchestra, dressed in the most varied, the most picturesque, the freshest costumes, and some of which, I must say, are worn with a cranial, quite aristocratic ease. It really feels like being in the world and in a most elegant society.”)

Doctor Frédet, cited in Froudiere, 141: “Ce sont ceux-là, je dois le dire, qui sont les moins tranquilles, qui font le plus de bruit, qui s’agitent le plus, et qu’un spectateur impartial prendrait peut-être, à première vue, pour les habitants de la maison.” (“These are the ones, I must say, who are the least quiet, who make the most noise, who are the most agitated, and whom an impartial spectator would perhaps take, at first sight, for the inhabitants of the house.”)

Froudière, cited in Froudiere, 135: “L’imitation de la raison pour les fous, l’imitation de la folie par les invités, ne sont au fond qu’une parodie; le travestissement dévore l’identité et devient en lui-même source de folie.” (“The imitation of reason for the insane, the imitation of madness by the guests, are basically only a parody; the disguise devours the identity and becomes in itself a source of madness.”)

Charcot’s reputation on both national and international levels came from the lectures he gave on Tuesdays (less technical and aimed at general public) and his private Friday lectures, reserved for scientists and medical students which attracted Parisian intelligentsia. Freud’s assiduity is well documented, as are Charcot’s faithful followers, including cultural figures such as: the brothers Goncourt, Guy de Maupassant, Octave Mirbeau, the patient and writer Alphonse Daudet, the patient and Moulin Rouge dancer Jane Avril, the acclaimed stage actress known as Rachel, and her successor Sarah Bernhardt, who was to develop maximalist expressiveness in acting for the stage. Charcot’s public performances also became highly regarded by the national and international medical community. Sarah Bernhard visited La Salpétrière in 1884, when she was preparing the madness scene in Adrienne Lecouvreur. Marquer, Les Romans de la Salpêtrière, 129.

Didi-Huberman, 281. “He was not a brilliant speaker, and loathed grandiloquence as much as he despised clichés. He spoke slowly with impeccable diction; he did not gesture; sometimes he sat and sometimes he stood. His presentation was always remarkably clear. He gave the impression of wanting to instruct and convince.” Georges Guillain, JM Charcot (1825-1893). His life, his work (Paris, Masson et Cie, 1955), 53–54. “Ces malades sont inconnus du Professeur qui cherche à établir séance tenante le diagnostic, le pronostic et le traitement de l’affection dont ils sont atteints. — M. Charcot fait assister ainsi ses auditeurs au travail qu’il accomplit pour élucider ces diverses questions.” (“These patients are unknown to the Professor, who seeks to establish the diagnosis, prognosis and treatment of the condition from which they are affected. Mr. Charcot thus assists his auditors in the work he does to elucidate these various questions.”) MM. Blin, Charcot, and H. Colin, Lecons du mardi a la Salpetriere (Paris: Aux Bureau du Progres Medical, 1892), 2.

Charcot quoted in Didi-Huberman, 183.

Expression by Didi-Huberman.

Delboeuf, Une Visite à la Salpêtrière (Brussels: Merzbach/Falch, 1886), 49.

Such as the “ovarian compressor.”

This deceptively gain-gain situation would have indefinitely perpetuated the dynamic named hysteria. Didi-Huberman, 171–174.

Mirbeau considered the spectacle offered by the lecons a “dream” from “troubled sleep.” In Marquer’s words, it was “the erotic dream of male omnipotence.” “Voici une femme qui entre. C’est là que le rêve commence.” Octave Mirbeau, “Le siècle de Charcot,” L’Événement, May 29, 1885. “Ce rêve, c’est celui, érotique, de l’omnipotence masculine.” Marquer, Les Romans de la Salpêtrière, 7.

This painting features Dr. Jean Martin Charcot, credited to be the founder of Neurology and leading investigator of hysteria of the time; Paul Richer, medical artist; Albert Londe, chrono-photographer, Jules Claretie, journalist and author of Les Amours d’ un Interne (1881) and who later became the administrator of the Comedie Francaise; and Blanche Wittman, one of Charcot´s most famous patients. Brouillet is not known to have sat in the room to portray the event while it was unfolding. We do not know whether he composed the group portrait from individual studies of each person represented; we do not know either if Miss Wittman posed for him or if her portrait was painted based on the abundant photographic documentation which was being produced and circulated by La Salpêtrière as an institution.

Octave Mirbeau, “La névrose au village,” L’Événement, March 29, 1885.

Mirbeau’s description closely resembles Brouillet’s painting except, and tellingly, for the lighting of the space and its windows. Mirbeau underlines the controlled low light that Charcot preferred to submerge his audience in. Starting from a dark space, Charcot chose which effects to employ.

Charcot, op.cit., p.6.

Marquer, Les Romans de la Salpêtrière, 232: “Le caractère épidémique de l’hystérie, métaphore de son intrinsèque pouvoir de séduction.” (“The epidemic character of hysteria, is a metaphor of its power of seduction.”)

Sick Architecture is a collaboration between Beatriz Colomina, e-flux Architecture, CIVA Brussels, and the Princeton University Ph.D. Program in the History and Theory of Architecture, with the support of the Rapid Response David A. Gardner ’69 Magic Grant from the Humanities Council and the Program in Media and Modernity at Princeton University.