Questioning the Potemkin Metropolis

The interplay of rhythms—the rhythm of urban capitalism and the body’s rhythmic propensities—sometimes synchronize. But often, they clash.1 At Singapore’s Central Business District, tall buildings embossed with logos belonging to financial corporations look like grey calculators during the day and powered down robots at night. These buildings stretch across the city-state, district after district, wherever capital flows. In 2020, Singapore ranked first out of 173 economies in the World Bank’s Human Capital Index, beating Hong Kong, Japan and South Korea into second, third, and fourth positions respectively. Singapore, it appears, is the best country for developing human capital based on the quantification of a worker’s skill set’s economic value, or productivity.

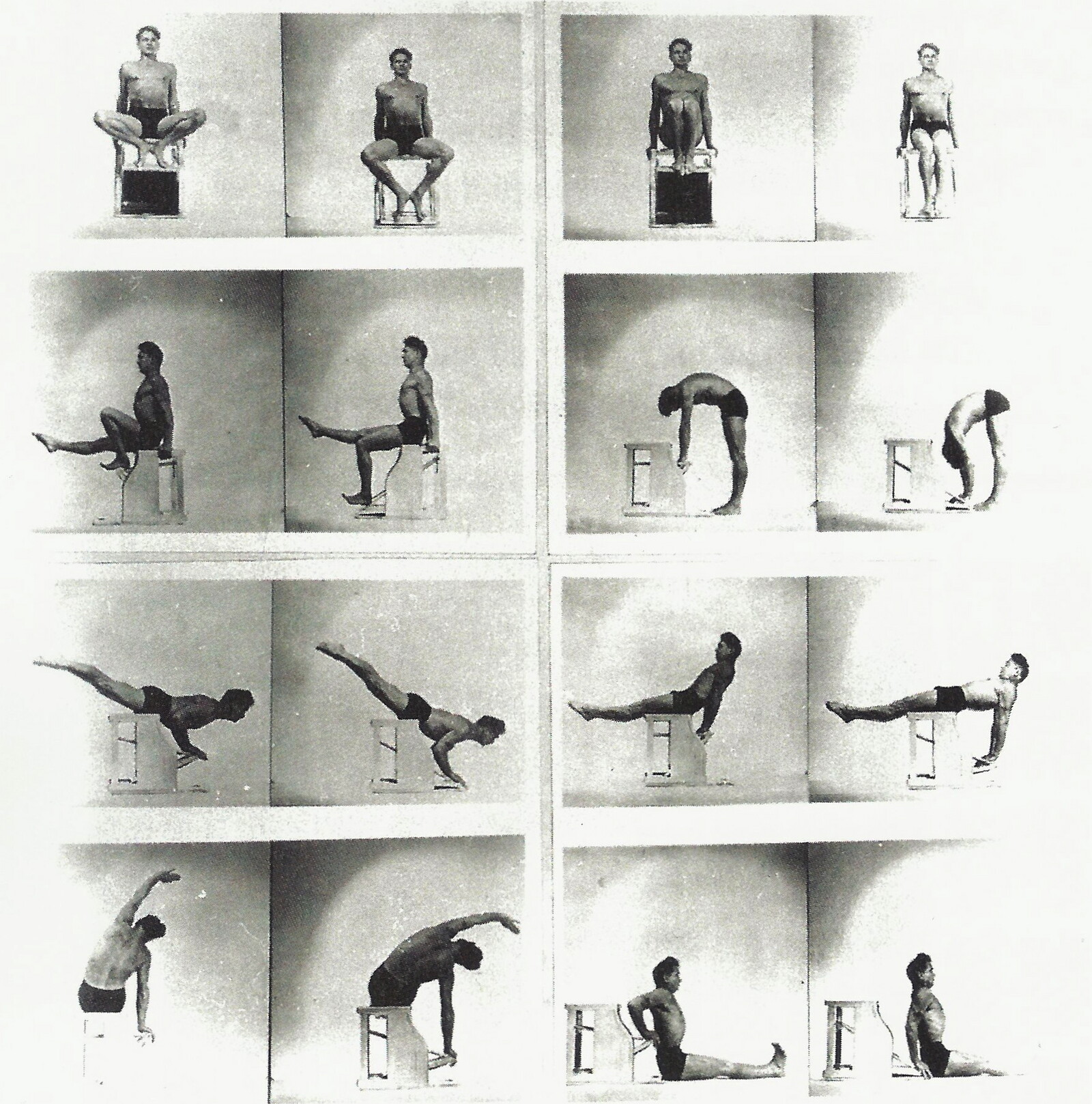

At about 5:30am, joggers heave and puff along the Singapore river. Maybe an early morning cardiovascular activity is part of getting ahead, of keeping up with the pace of the city before the tropical sun inches its way up, slowly above the behemoth calculators. Standard Chartered, Great Eastern, OSIM Sundown, Singapore Bay Run et al. are the “must-do” local marathons and runs. Joggers wear lightweight shirts with the distances they have achieved on them: 42.195 kilometers, 24 kilometers, 12 kilometers, 10 kilometers. In the evening, the Singapore river flirts with the glimmers of lit skyscrapers reflecting on its watery surface. The city slows down, the birds trill overhead, resident-chatter subsides. Buildings diminish in their vitality, recede into the lull of the waves, into the granite steps hopscotching to the jetty.

According to Nigel Thrift, affect is “a constant of urban experience.” However, the role of affect in the governance of cities has changed with planetary urbanization. Thrift offers his take. First, “affect has become part of a reflexive loop which allows more and more sophisticated interventions in registers of urban life.” Second, such epistemic thresholds “are being deployed knowingly and politically to political ends: what might have been painted as aesthetic is increasingly instrumental.” And third, “affect has become a part of how cities are understood … and cities must exhibit intense expressivities.”2 Following this paradigm of the affective city, the “intense expressivity” of Singapore’s first-world global brand, at a glimpse, is that of a high-GDP, high-productivity, finance-focused, cosmopolitan city and “tax haven” for the global elite.

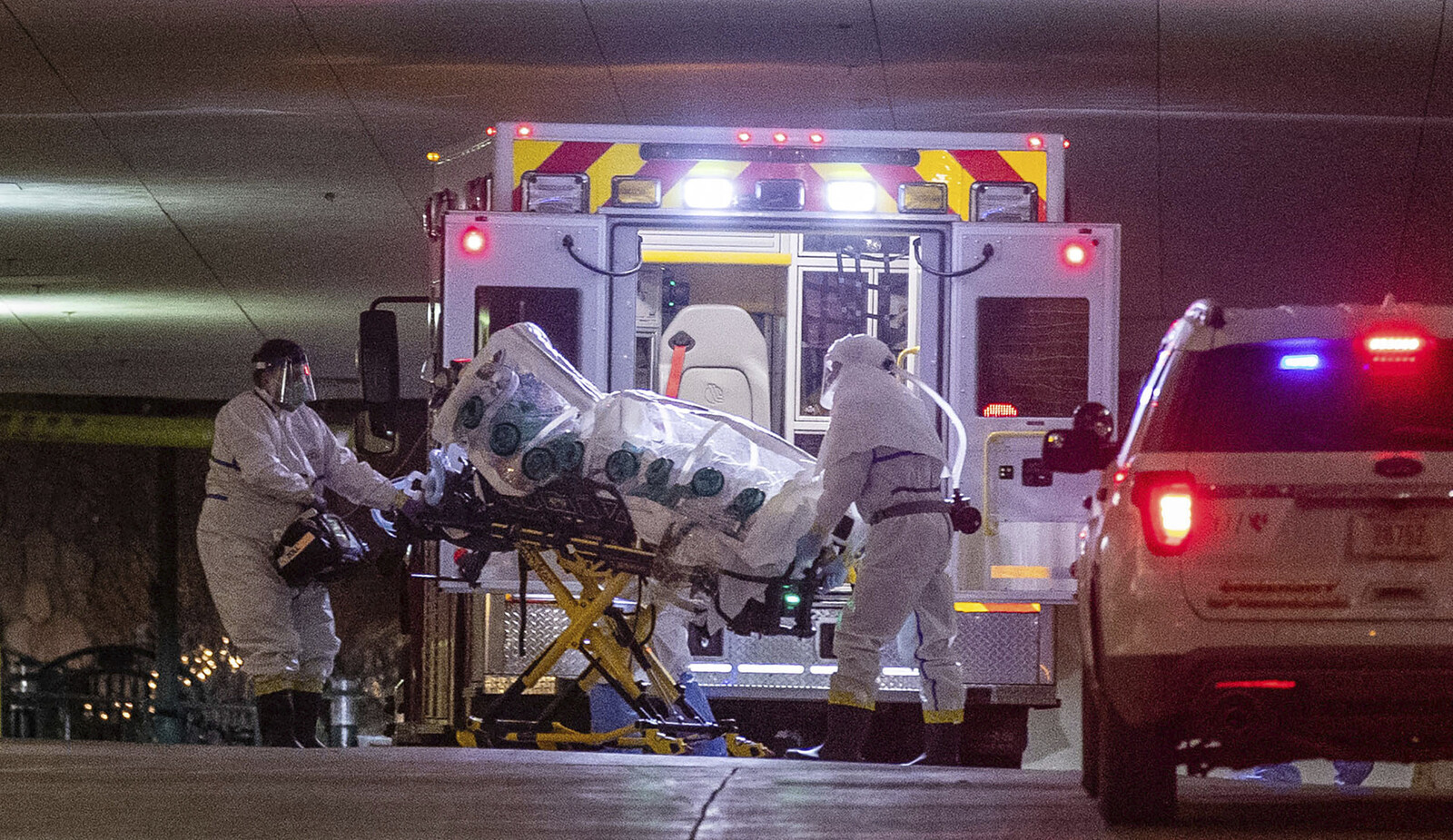

On a statistical register, however, Singapore appears depressive. For instance, in a 2016 Ministry of Manpower study, in comparison to Japan’s 1,735 hours and South Korea’s 2,193 hours, Singaporeans clocked 2,371 work hours yearly—the longest in the world.3 In 2013, 7% of Singapore’s workforce has had a history of mental illness, but only two out of ten mentally ill people in Singapore sought treatment, according to a senior consultant psychiatrist at the Regional World Health Summit.4 In 2012, Gallup Poll ranked Singapore first as the most emotionless country in the world.5 Yet nine years later, in 2021, a Forbes contributor wrote an article titled “Singapore: An International Model for Mental Health.”6 The Forbes contributor failed to mention the reason behind Singapore’s newfound efforts to strategize mental wellness for the population, crucially during the Covid-19 pandemic. Migrant workers, mostly men from India and Bangladesh, bore the brunt of isolation and the spread of the infectious disease in crowded dormitories.7 There too arose distress calls from queer folks for counselling during the prolonged lockdown.8 Then, there is the teenager who was recently charged for murdering his schoolmate with an axe.9

Singaporeans and residents of the city are neither emotionless nor stoic; unproductive nor weak. Given Singapore’s history of hyper-modernization, models of economic pragmatism, exceptionalism, and scientific entrepreneurialism that have fascinated many “Western” nations, the neo-authoritarian Chinese state, and other countries in the Asia Pacific region (the “Asian Tigers,” ASEAN, Japan), almost everyone in Singapore can hold a conversation about finance, money, technology, progress, and its first world sensibility.10 And yet, when it comes to emotions, the nuance between sadness and depression, the range of how one feels, or politics beyond provincialized grounds, the conversation staggers.

Depression is difficult to trace in the city. In social scientific literature, the study of depression has been beleaguered by unresolved conceptual problems. In the 1980s, depression was “considered mood, symptom, and illness, and the relationship among these three conceptualizations remains problematic.”11 In the 1990s, the attention to mental health reflected anthropological concern with issues of social suffering, and could be seen as grounded in conditions of upheaval.12 In the new millennium, tragedies persist.

Along the way, “no health without mental health” became World Health Organization’s axiom.13 But the making of a global mental health is rife with issues.14 The world is witnessing an “open-source anarchy” around global health problems.15 Derek Summerfield argues against a universalizing “global mental health,” cautioning that psychiatric universalism risks being imperialistic.16 Living “in the wake” of postcolonial, post-slavery globality, forms of “medical imperialism” continue to circulate.17 Classification paradigms drawn from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) simply may not cohere to the range of plural phenomenologic representations of Singapore’s citizens and residents.

Mental health literacy and mental healthcare were not seen as societal priorities, until recently. One could sense there are people who need a mental health break, or at least need an expressive form; simply a talk for it. On a linguistic register, the creole that is spoken most of the time amongst Singaporeans and residents in both professional and non-professional settings is “can” instead of “yes” or “okay.” Singapore can be seen as an achievement society, and the inhabitants of such society are “achievement-subjects.” The “achievement society,” according to Byung-Chul Han tends towards over-saturation. “Unlimited Can is the positive modal verb of achievement society.”18 Han later says: “Depression is the sickness of a society that suffers from excessive positivity.”19 In Singapore, positivity is discernible in expressions like everyday language and state messaging. Depression remains invisible, or opaque. Take, for instance, The Invisibility Project, an exhibition curated by Jasmine Ann Cooray showcasing collaborative works by poets and visual artists in Singapore.20 In speaking to and with the theme of “Invisibility,” Tania De Rozario, a Singaporean artist wrote a poem called A Eulogy:

for everyone distilled into colour

of skin, use of pronoun, place

of origin, length of hair, years, skirt,

name, limbs, medical record.for everyone made to believe

that the petals of persecution

blossomed from the buds

of their own paranoia.…

for everyone accused of prolonged

adolescence, scars on their arms

marking time like a calendar, body

taking itself into its own hands.21

Here, poetic imagination speaks to the rogue intensities of everyday and structural violence. As with queerness in the sociopolitical context of Singapore, there is a salient hide-and-seek in the storytelling of depression. The stigmatizing and repressive forces which hit the queer and the depressed (both as separate categories and at the intersections) are reasons why they are unable to come out, forward, or to seek help. The costs of doing so are structural, punitive, and are intimately linked to the limited and unequal ways of attaining public resources. Once biographical details are in the panoptic-administrative record, one can expect discrimination: in the labor market, job applications, purchasing of homes, and healthcare access.22 Queer and depressive folks are perceived as unproductive in terms of biological and political reproduction (of children, viable citizens, norms) and in terms of work itself. And yet, the city is an open-ended assemblage of things: urban marginality, wealth, slowness, productivity, differences, performance art, poetry.

An Art of Existence

Somewhere in Marine Parade, a residential estate in the central region of Singapore where the shore meets the Strait, a cross-section of marginal life proliferates. Marcia and Sophia lived in a colonial-styled, semi-detached house in a gentrified coastal neighborhood with three cats roaming, playing, and people-watching on the front porch.23 In the summer of 2018, after three years—or multiple moon cycles, as she liked to say—Marcia waved to me from the front porch by the black gate. We sat for coffee. She told me about living with her partner. Rent is expensive in Singapore, she said, with a crumpled nose. Most Singaporeans live in public housing and own their homes for ninety-nine years, so long as they can verify being a heterosexual family unit to government officials. Affluent Singaporeans purchase “good-class” bungalows in exclusive areas—one of the ultimate status symbols—for real estate investment and intergenerational wealth transfer. Same-sex marriages and civil partnerships legalized abroad are not recognized in Singapore, and no anti-discrimination protections exist for queer folks. “We make do, Sophia and I,” Marcia said. “We finally found a job. Full-time. Advertising likes butches. The arts like petticoat-wearing lesbians.” Freelancing and living with friends in small spaces were the former rhythm of their lives. The couple’s rented home is a corner of the world that is theirs.

We then walked by the sea. Marcia was on medical leave, still recovering from breast cancer surgery and excused from her lecturing duties. “I affectionately call my performance art as performing black magic. And this breast cancer, to some local conservatives, is seen as a God’s curse.” As an artist, Marcia has sculpted tiny funerary boats with lopsided faces, ate vagina dentata sugar cookies which she baked at home, and crafted palm-sized, bright-colored effigies, burning them to placate her many deities under the waxing gibbous moon. Wherever she goes, the aroma of spike lavender incenses the tropical air. Polytheistic ritual is a performance, an art form to her. Artmaking is the fulcrum of her universe, her steady footing on the wispy plane of provincial homophobia, and her potent mana against the opprobrium of being mixed race and a lesbian woman. Marcia is outspoken and out of place in the neat hierarchy of race, gender, and sexuality in Singapore. Somewhere in the course of her life, depression was an impasse she swerved around. She was disowned by her parents for years, but was now reconciling with her family.

We looked out at the sea and at the vessels—freighters, containers, and supertankers—dotting the horizon. These were ghost ships anchoring idly in the Singapore Strait, some with nowhere to go as their businesses went bust. The Strait supposedly functions more efficiently than other shipping passages such as the Suez and Panama canals. At the time, there were many collisions occurring in the Strait, with ships’ keels pointing upwards, hulls turning over, infinite sheets of suspended blue-green water crashing down, becoming a part of the sea. From afar, there was symmetry of land and sea. White-crested waves crashed on our feet. We then walked back to her house. At Marcia’s front porch, her cats resumed their guard duty. There was an arts and crafts table near her garden. On the table were jars of sacred medicinal plants like Solomon’s seal. Next to the table was a painted stool she was air-drying inscribed with a Javanese pregnancy charm her mother and sisters had used. The charm was her way of healing from familial estrangement after coming out.

I was not invited into her home because Sophia was working, either Skyping with a client or chasing a deadline. It was also because Marcia and I had been three years, two time zones, and 10,000 miles apart. In my field of vision, Marcia stood on the front porch, flanked by the couple’s three cats. Marcia uttered with parting finality: “let’s hang out soon when you are back again.” Her words dropped, a staccato. A thought in the act of an old friend’s farewell as syllables parsed and partly unfolded to gesture towards another temporality, an interior-future, an assertion of soon and again. An accretion of the maudlin sensed, of the becoming of things in absentia: Marcia’s art exhibition, house parties, adopting another cat, going through another breast cancer surgery; my growing estrangement from Singapore, the bruised grace of memory, the becoming of me that I would become. Life is a constant relay of correspondences, a mode of composition in flux, simultaneously “resisting synthetic ends,” as anthropologist João Biehl puts it, and creating pockets and portals for recompositions and decompositions.24

Ethnographic Poiesis

Depression is a penumbra that has a creative force in queer performance art. There is a sense of anonymity, loss, exclusion, and rupture associated with being queer and/or mentally ill in Singapore. Artists, while living with the stigma associated with queerness and/or mental health conditions, build political coalitions out of the affective—and opaque—material of their lives. Queer art creates a space for transgressive worlding where expressions of urban marginality are allowed, but only under certain socio-legal regimes of an illiberal democracy. By worlding, I refer to anthropologist Kathleen Stewart’s expression: “the lived affects of someone spinning out of control, or deflating, or shouldering tasks and identities in the effort to succeed, or to survive, or to find something.”25

To avoid hypervisibility and stigma, many marginalized artists engage in a dialectic of opacity, expressing that they want to be seen but don’t want to be exposed. This is a new language in line with their ways of dealing with everyday policing in Singapore, and a clear discourse in queer performance art. Worlding through the arts is a form of storytelling; a means of plugging holes, of harnessing the potentiality to remake one’s society.26 Worlding, then, is the vicissitude of the many effects of modernity where one does not have a transcendent such as the welfare state or wherein one lives in a democracy under jeopardy. The pleasures of worlding through performance art come about and are experienced in ascertaining an ethics in a world that does not provide it. The external environment, then, is not taken as a threat, but as “a foundation of Relation,” in the words of Édouard Glissant; one that always gestures towards “freedoms” and other political possibilities.27

Worlding in Theory

At the Ocean Financial Center, a Singaporean traveler carried a wad of Singaporean dollars to exchange cash into two different currencies: to American dollars and Japanese yen. 1 Singaporean dollar equals 0.74 American dollars. 1 Singaporean dollar equals 81.89 Japanese yen. With 1 Singaporean dollar, the traveler could pay the tax for six ounces of latte at Small World Coffee in downtown Princeton, New Jersey. With 1 Singaporean dollar, the traveler is short of two yen to buy a bottle of matcha tea from a vending machine in the Narita International Airport. At the Ocean Financial Center, 1 Singaporean dollar is a burnished yellow coin. Minted onto this coin is either the stencil of the national orchid or the state-manufactured mermaid-lion hybrid.

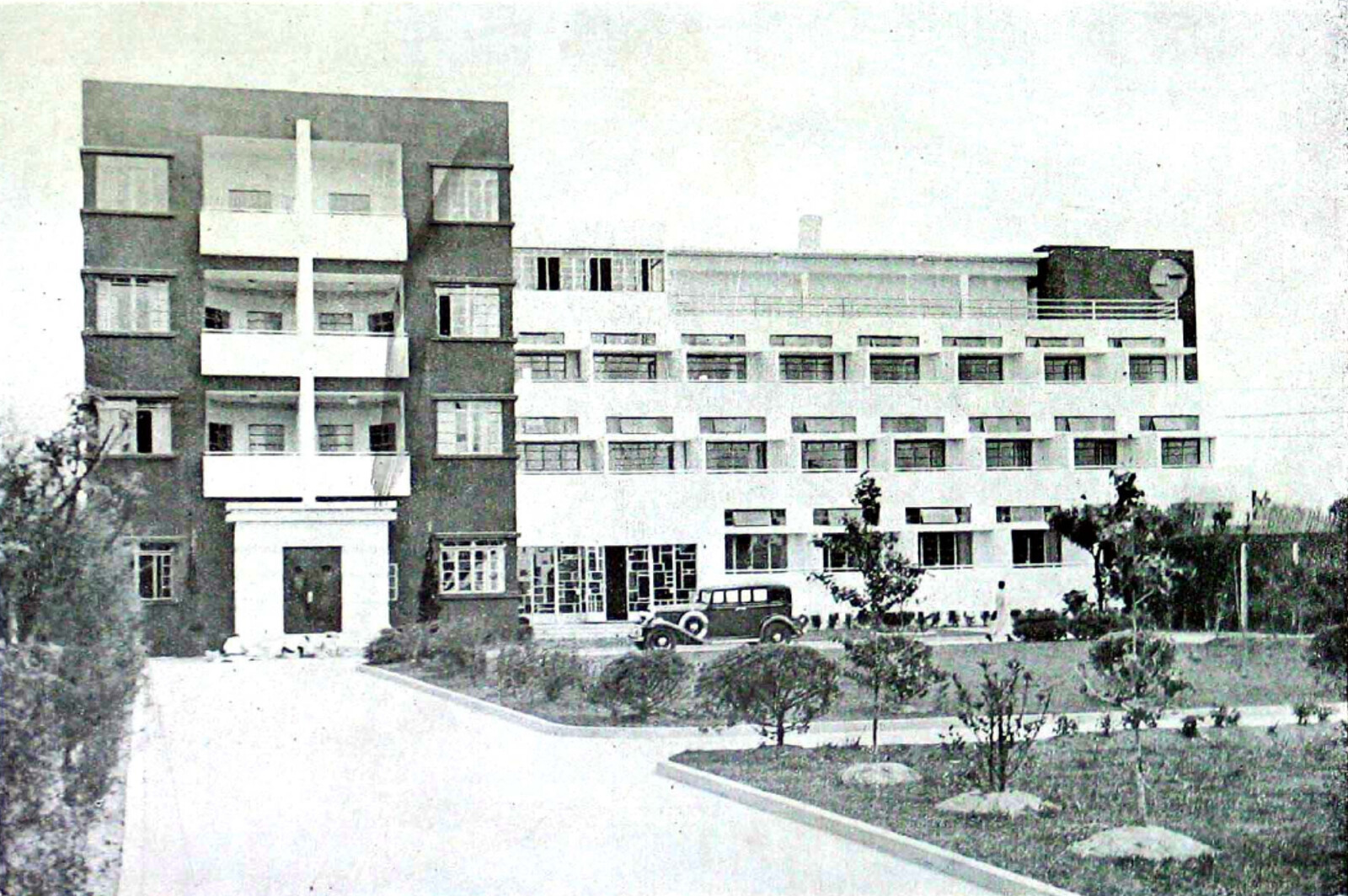

The levers of Singapore’s DNA can be tweaked depending on what one is observing, or whenever the government decides to have something beautiful expediently built, but only by tearing down something else. This happens often. It can be alarming to not be able to tell the age of the buildings. Aging or otherwise, Singapore has established an impressive array of built and spatial forms since gaining independence in 1965—after the histories of European colonialism (Portugal, the Netherlands, Britain are the usual suspects), Japanese occupation, and then expulsion from Malaysia. The architectural landscape of the twenty-first-century, first-world Singapore tells her postcolonial “success” story.

There is the “keychain architecture,” like the Marina Bay Sands and supertrees of the Gardens by the Bay, which offer iconic views to anyone who wants the fetishized commodity of a visual memory-souvenir.28 There is generic architecture like public housing, which while properly homogenous, still reveal their age—that is, whether they are matured home estates or not. There are outlier spaces like the Somerset Skate Park, a 3,000-square-meter playground with ramps for skaters seeking concrete refuge. There are accidental outliers, guerilla-style spaces that create small worlds for subcultural communities, like the artist-run space Starch at Tagore Lane and the now-homeless independent contemporary arts center The Substation.

Singapore may characterize the Generic City, given her tabula rasa, nervous, “third world to first world within a single generation” energy. But Singapore is not the Potemkin metropolis Rem Koolhaas details in S, M, L, XL.29 Singapore is understudied and misunderstood under the Western Orientalist gaze. Diametrically opposed to the Koolhaasian Generic City, Singapore is a particular city, as most, if not all, cities are. She is beyond the exotic, the ornamental and the clichéd representations found globally, even locally. Historical traumas may inform her plasticity as a metropolis, but they do not determine it.

Built, spatial, and cultural forms can shape moods, govern daily rituals, probe certain political imaginaries and not others, and lead to an impasse of thought, emotion, and forms of living. Michel de Certeau speaks of walking as a spatial and space-producing practice where the walkers of the city transform spatial signifiers in real-time.30 Walking with Marcia represents an approach to the urban sensorium. The relation between us, her, me, and our surrounding milieu generates a strategy of sensorial perception where our bodies’ motion enhances the experience by immersing in the street. It creates a kind of attunement, a sensitive panorama of the urban experience in the everyday life. One enters dissonance with phenomena that try to reshape oneself. Worlding is simultaneously an anthropological and architectural question.

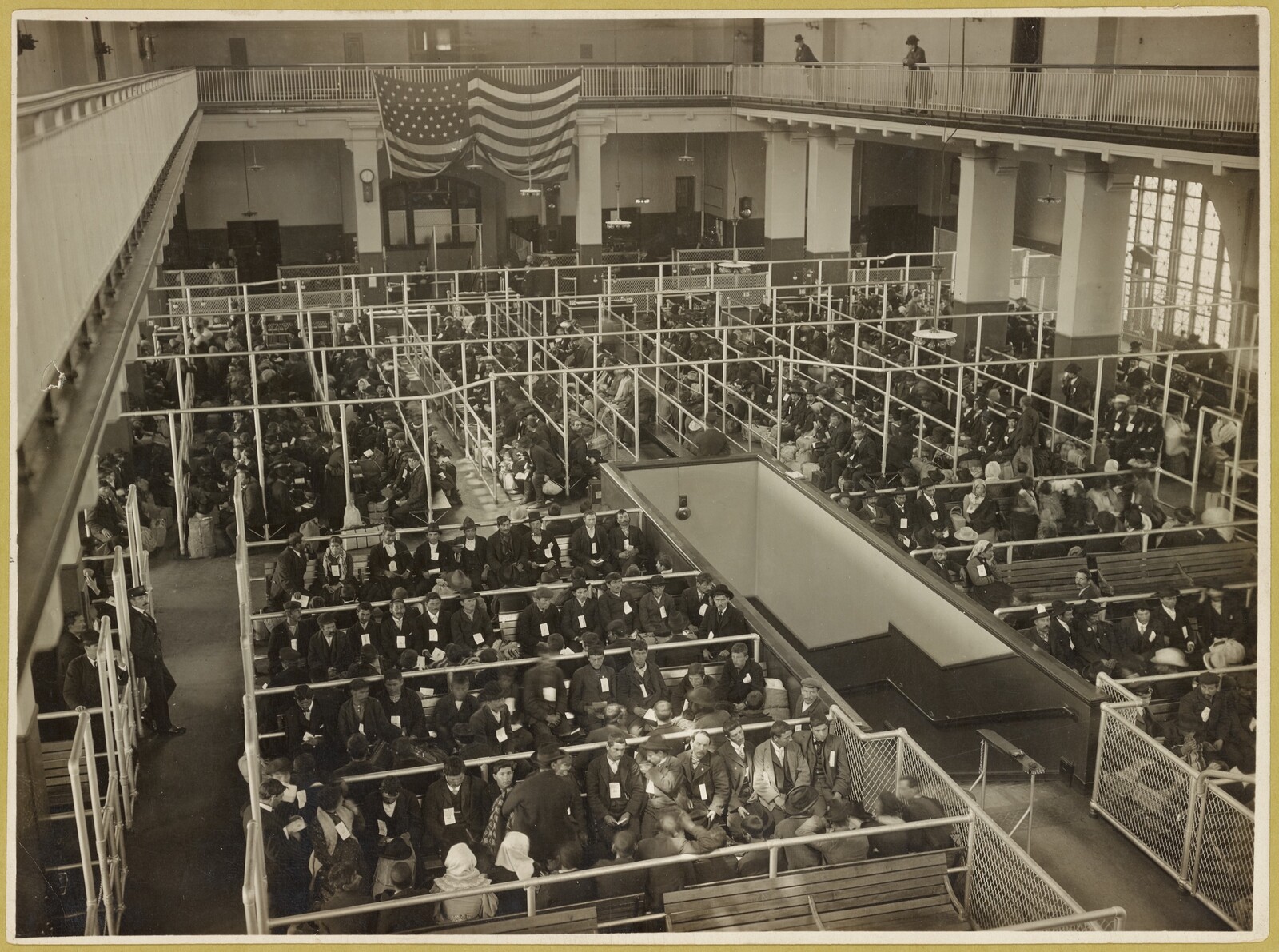

The sensoria of living in a world is nothing neat nor innocent. In the United States, for example, every sense of a world lives the afterlives of settler colonialism, slavery, and strands of inequality.31 In Singapore, the state makes worlds with frightening precision at the level of public policy, like its selective immigration policy, or the hyper-creation of heteronormative families, households, and relations that inevitably stigmatize queer/raced/classed bodies. But there are minor worlds proliferating, running rampant in the city. Migrant workers, queers, artists, activists, international residents, the poor, ethnic minorities, and so on, create worlds out of their social position, within the ambit of their means and becomings. In the summer of 2021, for instance, a formal healthcare network called the Migrant Workers’ Group, a coalition of about twenty organizations and the Law Society Pro Bono Services, was launched to foster collaboration between organizations in enhancing legal awareness and access to justice for the migrant worker community in Singapore.32 Worlding can be seen as a political imagination capaciously defined, an appetite for doing politics—or simply life—right within certain boundaries; a sense of justice; or futurity.

The anchor of a world can be in a performance; worlding can be seen as a kind of embodied performance. As a performance artist, Marcia investigated the Malay world of traditional medicine and found that much of its system is based upon the notion of air, and wind (angin). One of her rituals is to invite the audience to activate her installation by playing strings, bells, and percussion, thereby balancing their own air and wind through an intricate performance of healing arts. Marcia’s worlding seem to be allied with contemporary ethnographies of performance in Americanist anthropology, such as Aimee Cox’s choreography, defined as a mode of “integrating practices of improvisation, borrowing, and sampling to disassemble and reconstruct social realities,”33 or Dorinne Kondo’s reparative creativity, defined as “the ways that artists make, unmake, remake race in their creative processes, in acts of always partial integration and repair.”34

In August 2021, having moved my life-things from the District of Columbia to Singapore and before departing again for the eastern seaboard, Marcia finally invites me to her home. Her four cats are enamored by me, as I them. All good signs. I bide my time to bid Marcia goodbye. From estrangement to proximity, I am on the move again, though not poised to move on—to bracket away an ellipsis. I fumble. I want to crease the sheets of space, pleat the neat edges of time, lay my finger down to make crisp lines and fold the world to return to this place interlaced by the people I meet, in our constant flux of going and coming. The city’s sonic fugue, a score co-written, no matter how short the sojourn. My ears perk up to listen. The world is falling apart and in concert it opens an accidental space-time. Marcia closes her black gate. I walk alone to head to Changi Airport. The city is holding my hand. Along the horizon, the ships do not move. Yet every time moves relative to a person, a building, a matter. And every change is a monument to time passed, to time’s absence.

Henri Lefebvre, Rhythmanalysis: Space, Time and Everyday Life (London: Continuum, 2004).

Nigel Thrift, “Intensities of Feeling: Towards a Spatial Politics of Affect” in Geografiska Annaler: Series B, Human Geography 81, no. 1 (2004): 57–78.

Andrea Saadan, “Are we working too much? Singaporeans at risk of developing health problems due to long hours” in AsiaOne (July 28, 2017); Louisa Tang, “The Big Read: Breaking Singapore’s workaholic culture” in Channel News Asia (December 24, 2018); Derrick A. Paulo, “Facing depression: Working adults battle not just demons, but also stigma” in Channel News Asia (April 7, 2018).

Aik Heng Ang, Facing Depression (2019). Video Series for Channel News Asia.

Jon Clifton, “Singapore Ranks as Least Emotional Country in the World,” Gallup (November 21, 2012).

Garen Staglin, “Singapore: An International Model For Mental Health,” Forbes (April 21, 2021).

Jennifer Jett, “As Singapore Ventures Back Out, Migrant Workers Are Kept In,” The New York Times (December 17, 2020); Young Ern Saw, Edina YQ Tan, P Buvanaswari, Kinjal Doshi and Jean CJ Liu, “Mental health of international migrant workers amidst large-scale dormitory outbreaks of COVID-19: A population survey in Singapore,” Journal of Migration and Health 4 (2021).

According to reports from Oogachaga’s workshops on “Let’s Talk About…LGBTQ+ Suicide Prevention” and “Let’s Talk About…LGBTQ+ Mental Health” in October 10 and November 10, 2020, respectively.

The BBC Action Line, “Singapore shocked by killing of boy, 13, at school,” BBC News (July 20, 2021). These are some of the human tragedies that mobilized the government to kickstart a national mental health movement. Ministry of Health Singapore, COVID-19 Mental Wellness Taskforce Report (October 2020); Cheryl Lin, “New inter-agency task force to develop national strategy for mental health beyond COVID-19 pandemic,” Channel News Asia (August 24, 2021).

See Michael Fischer, “Biopolis: Asian Science in the Global Circuitry,” Science, Technology, and Society 18, no. 3 (2013): 381–406; Aihwa Ong, Fungible Life: Experiment in the Asian City of Life (Durham: Duke University Press, 2016).

Arthur Kleinman and Byron Good, Culture and Depression: Studies in the Anthropology and Cross-Cultural Psychiatry of Affect and Disorder (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1986), 2.

Arthur Kleinman, Veena Das, and Margaret M. Lock, ed. Social Suffering (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1997).

Martin Prince et al., “No health without mental health,” The Lancet 370 (2007): 859–877.

See Pamela Collins et al., “Grand Challenges in Global Mental Health: Integration in Research, Policy, and Practice.” PLoS Med 10, no. 4 (2013): 1–6.

David Fidler (2007) in João Biehl’s “Theorizing Global Health,” Medicine Anthropology Theory 3, no. 2 (2016): 127–142, 130.

Derek Summerfield, “Afterword: Against ‘global mental health’,” Transcultural Psychiatry 49, no. 3–4 (2012): 519–530, 525.

Christina Sharpe, In the Wake: On Blackness and Being (2016); Summerfield, “Afterword”: 525.

Byung-Chul Han, The Burnout Society (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2015), 8–9.

Ibid., 10.

The exhibition was held at The Arts House in 2013.

This is the excerpted version, not the full poem.

Recently, Tripartite Alliance for Fair and Progressive Employment Practices (TAFEP) has updated its guidelines, stating that all declarations on mental health conditions should be removed from job application forms.

Marcia’s and Sophia’s names have been changed.

João Biehl, “Ethnography in the Way of Theory,” Cultural Anthropology 28, no. 4 (2013): 575.

Kathleen Stewart, “The Achievement of a Life, a List, a Line.” In Nicholas J. Long and Henrietta L. Moore eds., The Social Life of Achievement (New York: Berghahn, 2013), 32.

Storytelling is an “existential imperative” to anthropologist Michael Jackson in The Politics of Storytelling: Variations on a Theme by Hannah Arendt (Copenhagen: Museum Musculanum Press, 2013), 32.

Édouard Glissant, Poetics of Relation, trans. Betsy Wing (Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press, 2010), 190.

I thank Singapore-based architect Razvan Ghilic-Micu for introducing this term to me.

Rem Koolhaas, “Singapore Songlines: Portrait of a Potemkin Metropolis… or Thirty Years of Tabula Rasa,” S, M, L, XL (Rotterdam: 010 Publishers, 1995), 1009–1089.

Michel de Certeau, “Walking in the City,” The Practice of Everyday Life, trans. Steven Rendall (Berkeley; London: University of California Press, 2011).

For examples, see Shannon Speed’s Incarcerated Stories: Indigenous Women Migrants and Violence in the Settler-Capitalist State (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2019) and Laurence Ralph’s The Torture Letters: Reckoning with Police Violence (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2019).

Aysha Farwin and Michelle Law, “Healthcare for migrant workers: More than just easy access to medical centres” The Straits Times (July 20, 2021); Dominic Low, “Migrant workers in S’pore better poised to seek help with launch of new coalition,” The Straits Times (July 11, 2021).

Aimee Cox, Shapeshifters: Black Girls and the Choreography of Citizenship (Durham: Duke University Press, 2015), 30.

Dorinne Kondo, Worldmaking: Race, Performance, and the Work of Creativity (Durham: Duke University Press, 2018), 5.

Sick Architecture is a collaboration between Beatriz Colomina, e-flux Architecture, CIVA Brussels, and the Princeton University Ph.D. Program in the History and Theory of Architecture, with the support of the Rapid Response David A. Gardner ’69 Magic Grant from the Humanities Council and the Program in Media and Modernity at Princeton University.