As far as Harriet Ann Brent Jacobs knew, life for an enslaved person was ghastly, and like many enslaved people she had learned to navigate the thin line between survival and death. When she fell ill, she recalled a “chilliness and deadly sickness” that came over her. Although she never received a diagnosis, one thing she elucidated was that during this period of being both enslaved and sick, she “prayed to die, but the prayer was not answered.” Her sickness had become part of her way of life, and for an entire year she rarely had a day without a deluge of chills or fever. For Harriet Jacobs, death was on the precipice of life.

This reflection on the interlacing of confinement, sickness, and mortality was documented in her autobiography, Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, which was written between 1853 and 1858.1 In this memoir, Jacobs moves from captivity to freedom through a series of harrowing trials not uncommon for enslaved Black women during the mid-nineteenth century. Jacobs’s memoir summons tragic watersheds from her life during her enslavement and after her manumission, the everyday anxieties on the plantation, and the plausibility of having her newfound freedom taken away.

Rapidly we retraced our steps back to the plantation. About half way [sic] we were met by a company of four patrols. Luckily we heard their horse’s hoofs before they came in sight, and we had time to hide behind a large tree. They passed, hallooing [sic] and shouting in a manner that indicated a recent carousal. How thankful we were that they had not their dogs with them! We hastened our footsteps, and when we arrived on the plantation we heard the sound of the hand-mill. The slaves were grinding their corn.2

But the thrust of what Jacobs describes from her life during enslavement and after her manumission existed beyond the lexicon of captivity; a state of unrest that inculcates how labor was toiled within a carceral landscape, where watchmen dictated and limited the movement of the enslaved. As she wryly notes, the plantation not only created the conditions that fueled psychological, physical, and sexual assault, but also incited a modicum of resistance. Throughout the text, Jacobs weaves together her desire to escape and her physical breaking points. One of these moments of entanglement came when, at the age of thirteen, Dr. James Norcom, who was her de facto enslaver, tried to sexually assault Jacobs. As a plantation owner, Dr. Norcom’s actions were hewing to the tenets of the evils of slavery—transgression, assault, and abuse. But Harriet came to realize something even more difficult, that some doctors, who were meant to provide care, were not only complicit within the plantation system, but were also meant to ensure that the breathing and thinking “property” could live under one condition: dejection.

When I first read Jacobs’ testimony, I was flooded with a wave of range of emotions, including the heavy weight of knowing that her enslaver, by design, did not have her physical well-being in mind, and that the infractions imposed planted the seeds of her suicide ideation. Jacobs shows how the relationship between slavery’s surveillance system and illness can bring the enslaved to wish for death. So many autobiographies of the formerly enslaved during this period—from Solomon Northup’s Twelve Years a Slave to Frederick Douglass’s Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an America Slave—open up about the brutality of the plantation as the site of social death. But in contrast to her male counterparts, Jacobs’s narrative is a nuanced exploration of a Black enslaved woman’s journey to freedom, her family history, and how the racial logics post-emancipation left many Black people in America neglected, tired, and broken. Her memoir is a cipher into malady’s journey into the plantation, and how the environment caused harm but also how the enslaved did their best to aid each other to full recovery.

Jacobs’ book bears affinity to the other markers of the freed who narrated confinement, sickness, and death on the plantation. For instance, in his autobiography From Slave Cabin to the Pulpit (1893), Rev. Peter Randolph sketches plantation life and malaise.3 The text is a conventional slave narrative of the time, highlighting his early childhood memories, his kin, and his path to freedom. In the fourteenth chapter of the text, he lists the full names of his friends, carefully marking their initials, when known. He justifies this chapter stating that these are the friends that have been part of “the changing scenes of my life.”4 This follows from an earlier point he makes in the text that “he who has friends must show himself friendly.”5 Randolph was enslaved with eighty-one other Black people by Carter H. Edloe on Brandon Plantation in Prince George County, Virginia. Unlike most of the enslaved on his plantation, Randolph learned to read and write. After lamenting about the perils of slavery, he noted: “The cholera came among the slaves and carried many to their rest. The very atmosphere, at this time, seemed to burn with evil and wrong for the poor Negroes, so that death was their best friend.”6 Randolph suggests that death was more appealing than a life of enslavement. But underlying his testimony is a disquieting reality: enslavement provokes outbreaks.

Slavery is often a condition that is remembered without giving voice to the enslaved. But as Yogita Goyal has noted, slave narratives provided the tool for the formerly enslaved to provide heartbreaking and sentimental appeals for abolition. Indeed, they do more than just that: they narrate how the enslaved were actively battling the menace of captivity, which reduced their lives, their labor, and the scope of their humanity to their skin color. For the formerly enslaved, these narratives were not merely literary devices, or memoir. They provide glimpses into the architecture of the plantation: a colonial concentration camp, the origins of modern policing, the site of medical racism, and a reminder of America’s hypocrisy. For Harriet and Peter, writing was their method for signaling how the plantation was the site of contagion and morbidity.

Cholera marked life and death in mid-nineteenth-century America, but how it was documented was predicated on one’s proximity to freedom. With nearly 40,000 reported cholera deaths as of June 1850, the pandemic hit every layer of society.7 Well into the middle of the third wave of the cholera pandemic in the nineteenth century (1846–1860), two US presidents perished from the disease. President James K. Polk died of cholera morbus in 1849 and his successor, Zachary Taylor passed away from cholera one year later. While elite and free persons had their death recorded in state mortality records, enslaved people were listed in the census by their enslaver, not as their individuals.8 Cholera was a ubiquitous and mysterious force then, and when we look back today, we find that the source of this plague was all in the water. Contaminated water is a medium that fuels cholera’s carnage, yet cholera can also be contracted by ingesting food that has been contaminated by excrement that harbors the bacteria. It is the microbe that causes diarrhea, vomiting, muscle cramps, sunken eyes, wrinkled skin, ruptured capillaries, and, if left untreated, death.

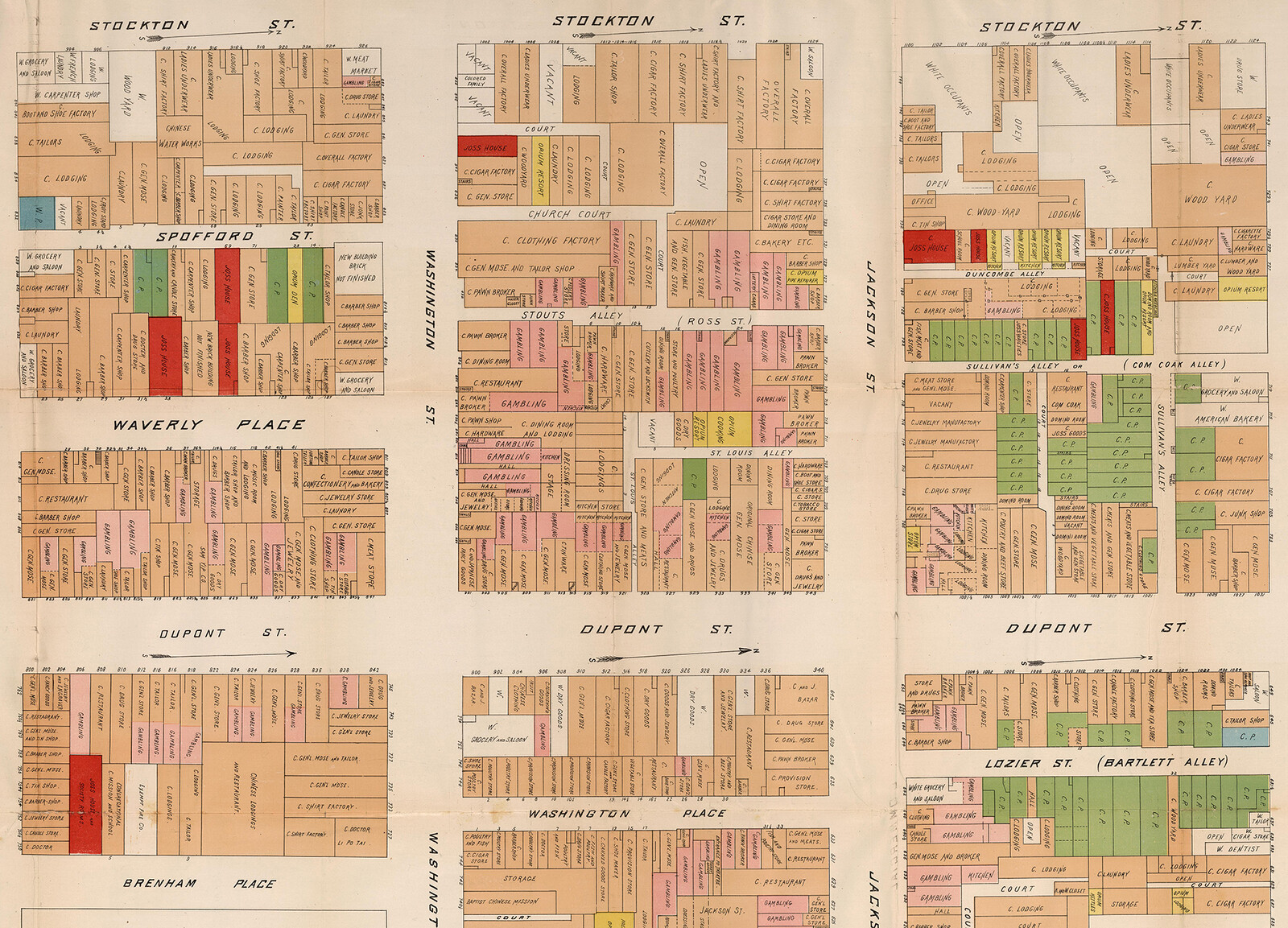

Before Filippo Pacini and Robert Koch’s independent discovery of the bacteria Vibrio cholerae was widely accepted as causing cholera, during the mid and late nineteenth century everyone had an opinion about how and why the malady spread. In his writings Die Cholera Morbus, Friedrich Schnurrer (1784–1833), theorized about the pathology and produced a map of cholera, arguing that there was a relationship between human settlement and cholera prevalence.9 He believed the built environment was strongly connected to the spread of disease and opined that epidemics are connected to geography. How this played out in major cities took different turns. In 1854, John Snow famously traced the source of the cholera outbreak in London to a water pump, eventually persuading Public Health authorities to remove the contaminated pipe.10 Amidst Snow’s great experiment was a period of reprieve for people in cities, who benefitted from public health departments and structural programs to stave off cholera. These gains were not experienced by everyone. For the enslaved, there was a different rubric for public health. In some cases, it led enslavers and their doctors to theorize about plantation medicine, while in others, an outbreak contributed to revolt. The social and political course of contagion on a plantation created unseen forces—some infectious, others latent.

Enslaved Community and the Intimate Horrors of Contagion

In the United States, cholera was perceived as an urban problem, especially given cities’ stronger and more direct links to the wider world. As the historian of medicine Charles Rosenberg noted: “Cholera could not have thrived where filth and want did not already exist; nor could it have traveled so widely without an unprecedented development of trade and transportation.”11 Cholera had a different life in plantations than in free society. As historian Diedre Cooper Owens has noted, the value of Black life shifted during slavery, leading to an investment in plantation medical science, and a constellation of ad hoc medical practices.12 Plantation medicine was not only used to manage endemic diseases; during the height of epidemics, enslavers also sought advice from doctors and consulted medical pamphlets that specifically focused on the plantation, such as Practical Rules for the Management and Medical Treatment of Slaves, in the Sugar Colonies.13 While much can be said about the cholera outbreaks in nineteenth century cities such as New York City, the plantation was a glaring example of the effects of captivity on disease. Health’s iteration—in the age of cholera—were filtered through a patchwork, racialized medical geography, and fueled by pamphlets. The social-medical contract was based on the will of an enslaver and his network, not the greater goal of the public’s health.

The story of cholera on the plantation is not only about the nature of the disease, but how Southern and Caribbean slavery lacked the capacity and will to undo harm for the enslaved. The network of medical pamphlets that sustained the architecture of the plantations also upheld medical racism. In Dr. James Ewell’s The Planter’s and Mariners Medical Companion, one of the authors reports that cholera was one of the most common diseases on plantations.14 Published in 1807 at the price of $50—equivalent to $1,500 today—and dedicated to Thomas Jefferson, the text was used as a medical “advice book” for plantation owners to provide direct treatment to the enslaved.

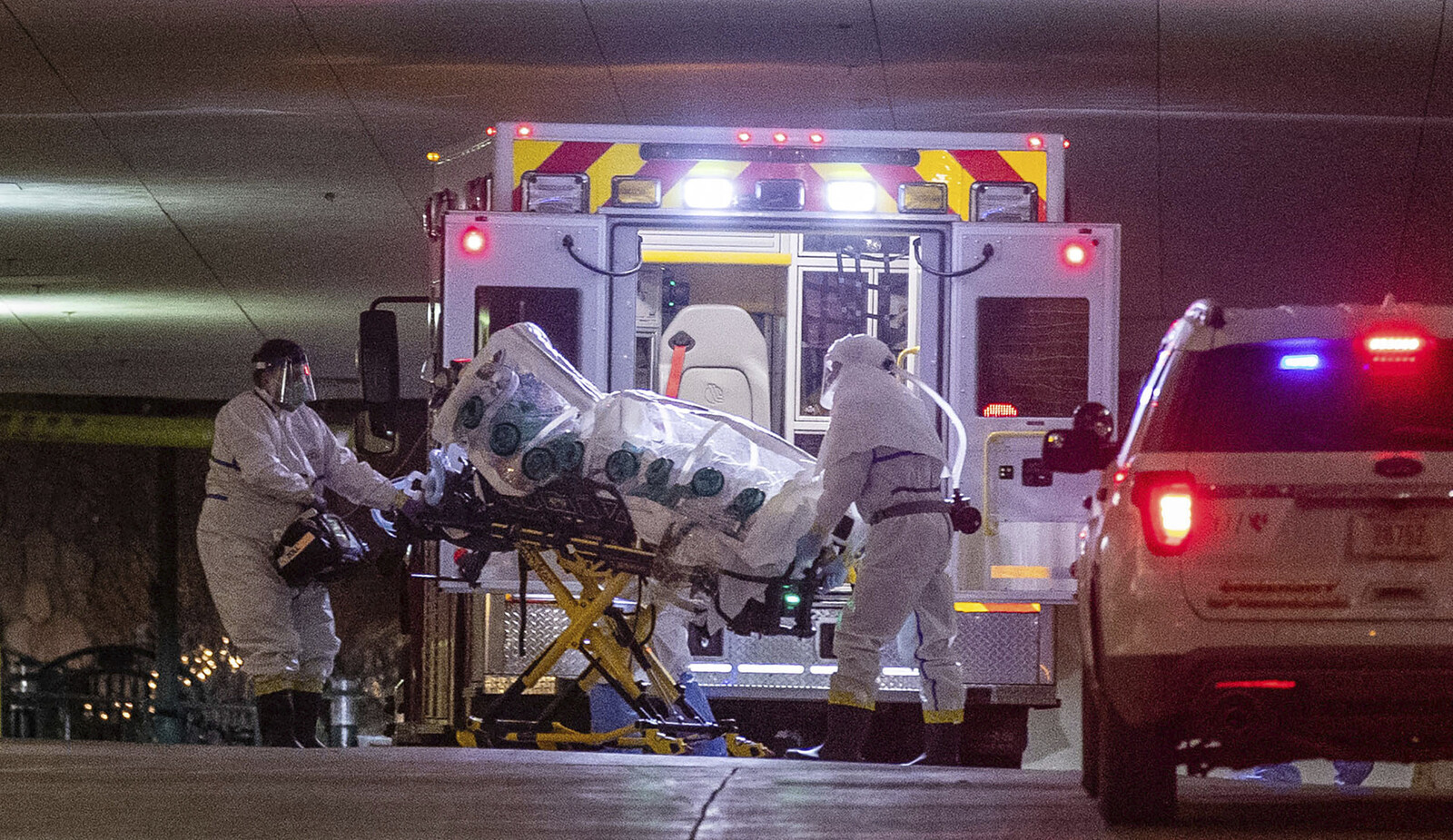

On May 1, 1850 R.N. Featherston, a plantation owner, wrote to Dr. New, a physician who specialized in plantation medicine, asking for advice on how to treat an outbreak of cholera on his plantation. Dr. New responded to the letter, which he later published into a modest pamphlet, indicating: “When a well-marked case of Cholera, fully developed in all the characteristics of the disease, appears on a plantation, I would advise the removal of all the well negroes to some remote comfortable buildings.”15 What New advocated for was a strict quarantine, like the recommendations of the International Sanitary Commission, which was established by the French government in 1861. Based in Rodney, Mississippi, Featherston used New’s pamphlet as a guide to isolate contagion. This correspondence was not unique. In fact, various plantation medicine manuals had been published to make accounts about modifying and thereby designing the health of enslaved Black people during the nineteenth century. While the ceaseless war on Black life was carried out in the United States, the necessity to keep Black people alive—especially during the cholera epidemic (1832–1866)—was predicated on the fact that both plantation owners and the vast regional, national, and global networks sustaining and benefiting from the system still wanted sufficiently healthy labor for the plantations.

That same year, Jamaica, then a British territory, also experienced a cholera outbreak, killing 30,000 people out of a population of 400,000. Although this was a period of post-emancipation, many of the newly “freed” Black people still labored in a brutal plantation economy that supplied cotton, sugar, and tobacco to the British Empire. The Scottish physician Dr. Gavin Milroy was called to provide treatment to the Black people working in and around horrifically afflicted plantations. He conducted research with fervid curiosity, hoping to understand how the cholera epidemic progressed. After months of travelling throughout the island and seeing firsthand what was happening, he became convinced that full emancipation would be the only way to mitigate disease, arguing that it was the only way to adopt sufficient sanitary reform to improve the health of everyone in Jamaica.

For enslavers like Featherston, slave mortality was principally tied to the profitability of plantation investments; while for physicians like Dr. New, Dr. Milroy, and Dr. Ewell, the practice of caring for the most vulnerable opened broader conversations about contagion and enslavement. Plantation medicine, as practiced by people like Dr. New and Dr. Milroy, was an uncomfortable space where doctors sought to treat the diseases of those who they did not fully deem human.

During slavery, enslavers also employed white physicians or Black midwives on an annual salary basis to treat the enslaved. One enslaver, John Pope, who owned a plantation near Memphis, Tennessee had land that was valued at $100,000, with seventy-five enslaved Black people.16 Given that the 1833 cholera epidemic had ravaged most of the Eastern coast of the United States, he decided to concoct a “remedy” which included “a spoonful of spirits of camphor with two of essence of peppermint and 25 drops of Laudanum” to the slaves who contracted cholera on his plantation. He claimed that using this remedy he “never lost a patient.” John Pope was not unique. Many apothecaries, doctors, and enslavers used a panoply of home-based reagents, hoping that it would prevent or treat cholera. In the preface of one of a popularly circulated text, Gunn’s Domestic Medicine, John Gunn indicates that the book provides medicinal plants “for healing our diseases.”17 For enslavers seeking homegrown antidote, Gunn’s manual provided a quick fix.

Even after slavery officially ended, plantations in the Caribbean were still, as in Jamaica, spaces where Black people were made to till the land, even as cholera continued to mushroom on the earth. On August 2, 1854, four years after the devastating epidemics in Mississippi and Jamaica, The New York Times reported that a cholera epidemic “swept over the plantations with a deadly effect” in Barbados, then a British colony.18 After six weeks of ravaging the island, 34,000 died. According to the report, more than a dozen doctors were attending to the sick, caring for the ill, and integrating a mixture of homeopathic methods. In other cases, ersatz doctors used prescriptions such as camphor, one of the early homemade remedies that had been used by cholera victims in Italy. One enslaver on the St. Philip plantation allegedly “cured” twenty-nine people by administering a spoonful of camphorated spirits and brandy to the patients. For him, the treatment was not just about providing the reagent; it also entailed giving the patients a clean dry room and covering them with a blanket, considered a privilege when compared to “normal” conditions. The report does not mention slave, or slavery, or the names of the people who died, but given that Barbados was one of Britain’s many slave economies, the majority of the infected were descendants of the formerly enslaved.

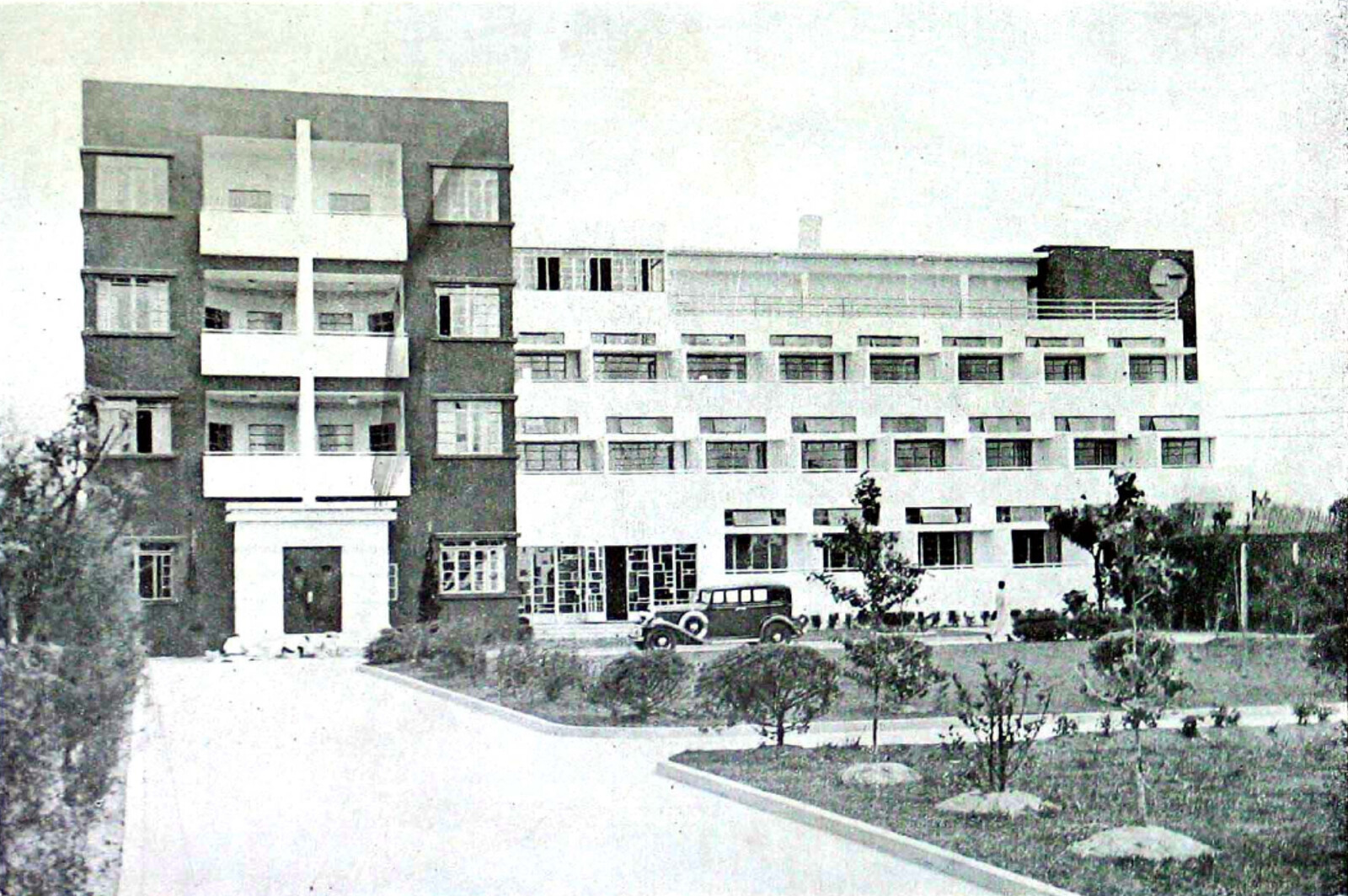

Part of the reason that these medicinal practices were homegrown is because the plantations experiencing such substantial mortality were almost uniformly located in regions that completely lacked public health facilities. Medical pamphlets for enslavers reveal the complicated reality of who was responsible for health—even during a pandemic. The failure of the slave economy to build a robust infrastructure, such as regional Health Boards, meant that the captive and unpaid labor systems were contained in a sphere that did not think it necessary to procure in everyone’s salubrity.

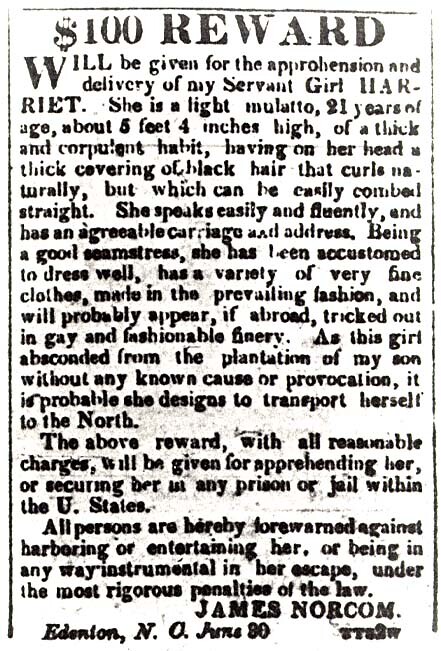

Reward for notice for the return of Harriet Jacobs by James Norcome (Dr. Flint). Copied from Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, which states that the ad ran in the Norfolk, VA, American Beacon newspaper on July 4, 1835.

Escaping Captivity

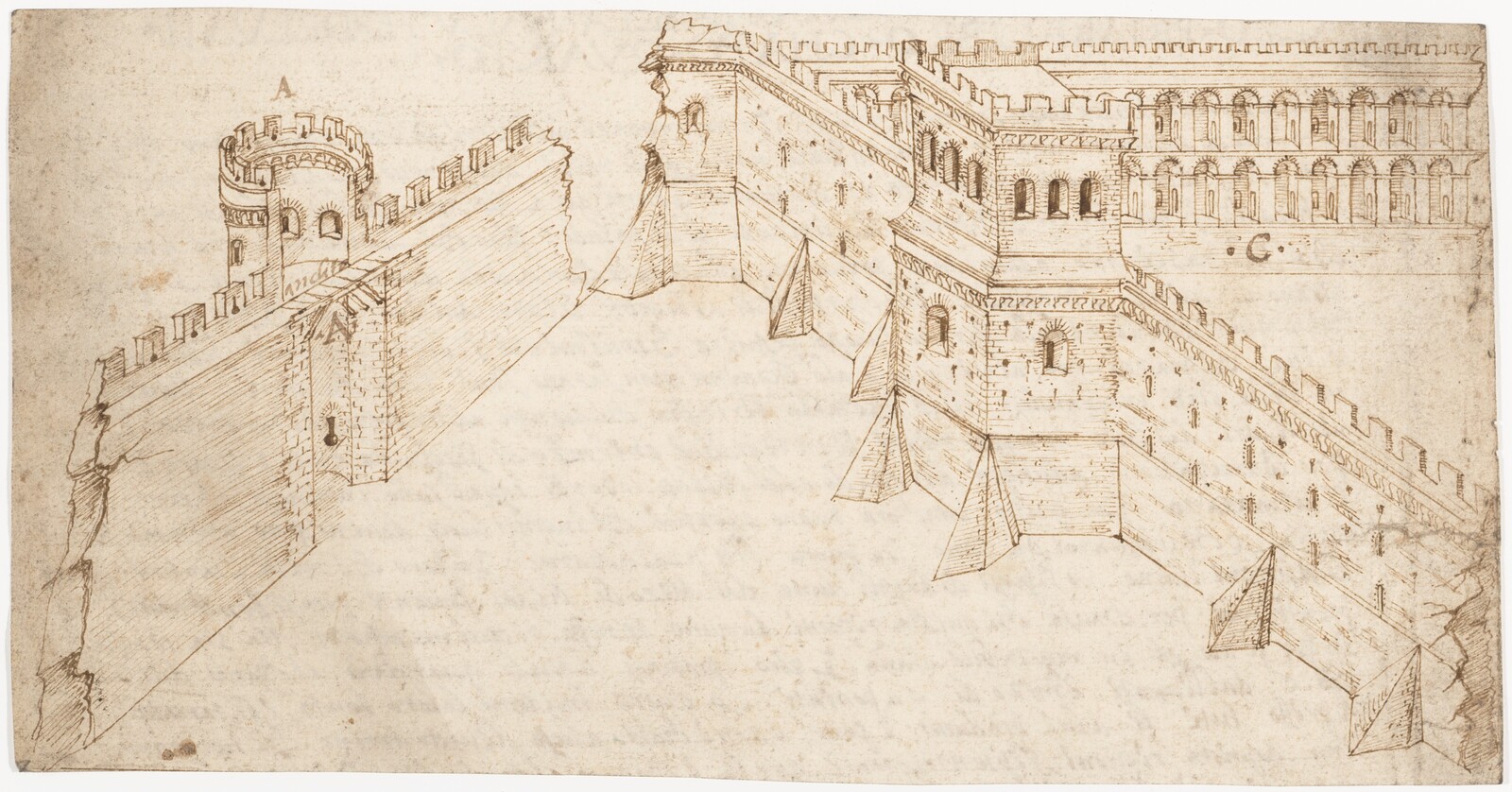

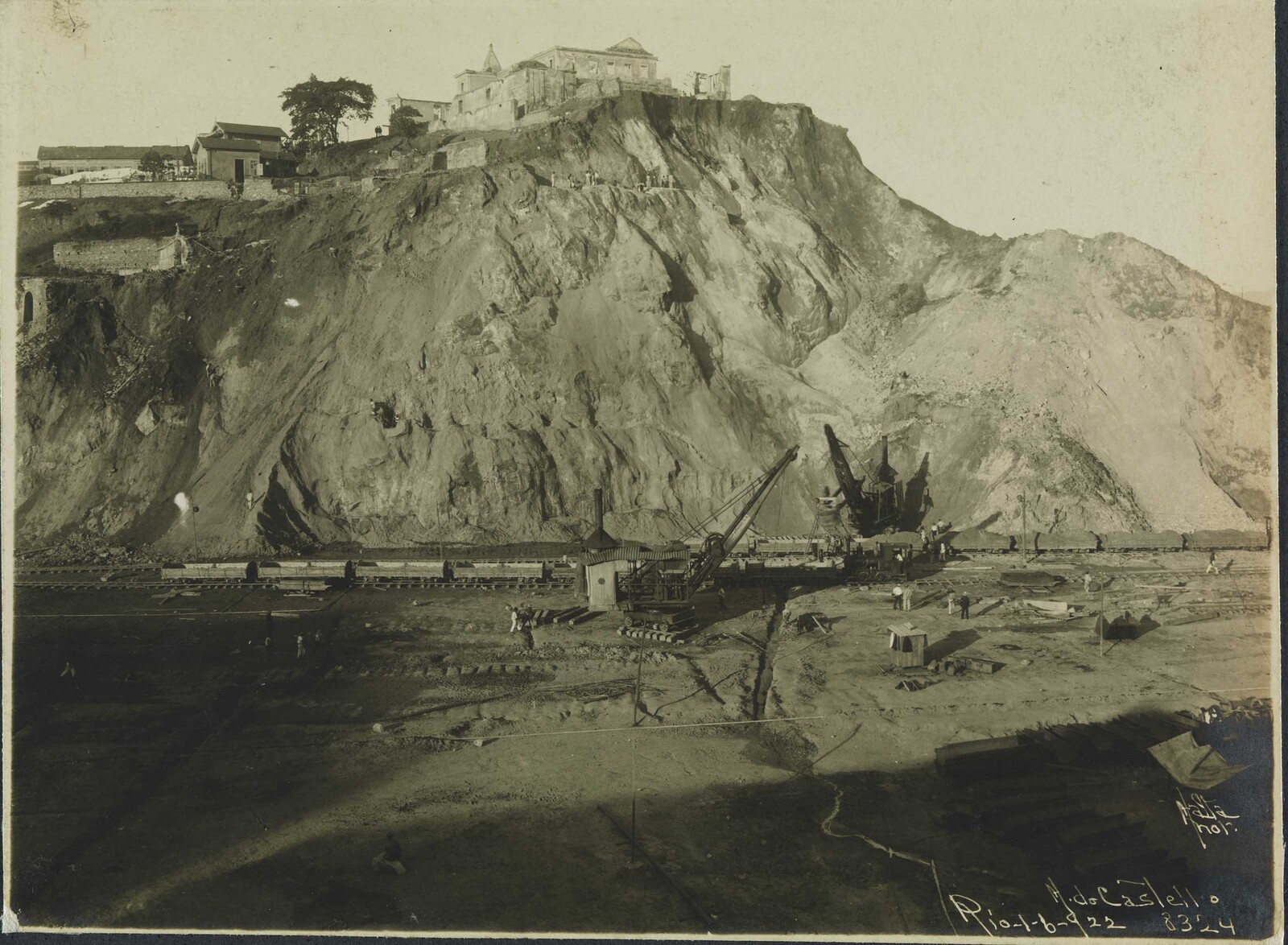

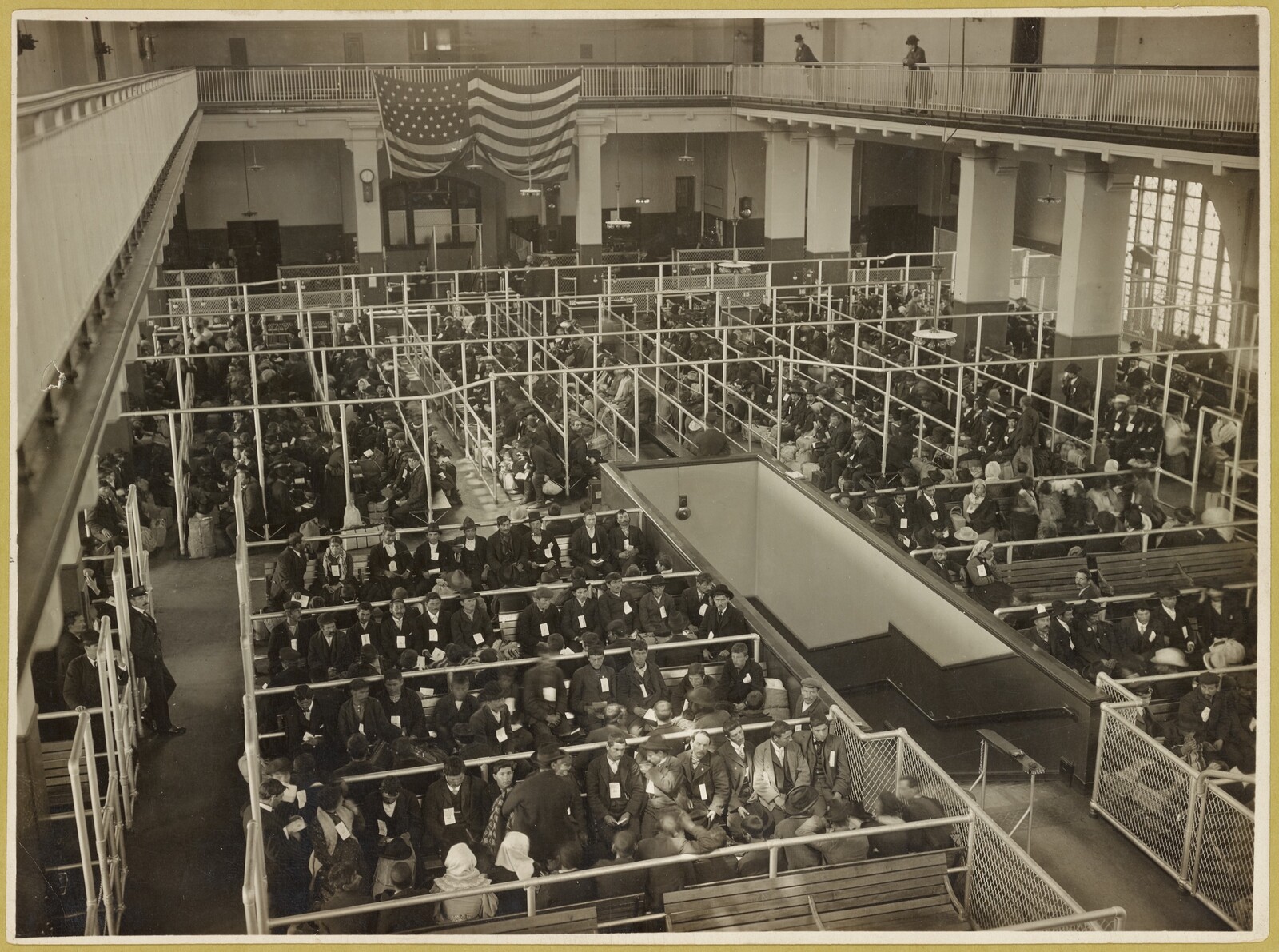

While much can be said about how epidemics play out with respect to public health measures, more can be done to understand the ways that space, movement, and socially constructed internment contributes to infection. How do we make sense of plantation medicine in times of an epidemic? Achille Mbembe evinces that the plantation economy was one of many technologies of colonialism that denigrated the body through total brutality, a mortifying reality wherein the everyday violence of the plantation created the conditions of making the enslaved more susceptible to illness.19 In Cabin, Quarter, Plantation, Clifton Ellis and Rebecca Ginsberg examine the architecture and landscape of plantation towns in the United States, highlighting how plantations adapted to control the movement of the enslaved people.20 They show how spaces of confinement mentally and physically compromise Black folks. Meanwhile, (formerly) enslaved people, mortified by the trauma of the everyday, saw in cholera the potential to escape enslavement, or even the never-ending trauma of life itself.

Approximately 1,000 miles apart, the slave economies of both Mississippi and Jamaica experienced simultaneous periods of outbreaks, with the enslaved and formerly enslaved the most susceptible to infection, which turned susceptibility to illness into resistance. Enslaved people in the American South and the Caribbean were also challenging their vulnerability to contagion by utilizing their own herbal remedies or escaping bondage. With little to no access to medical care, and acute susceptibility to ailments such as scurvy and measles, enslaved Africans were able to exercise agency over their bodies, implementing medical care for their own needs. African slaves used ginger to protect their immune system and castor oil to treat inflammation. Their use of plants and plant parts, from pine to turpentine, also offered them control of how to oversee their own bodies. The plantation economy is an important site of study today because coercive forms of medical intervention through confinement were conspicuous. The parable at the heart of the plantation system was bound to a new form of medicine, predicated on experimenting on the Black body. But this was not the only outcome.

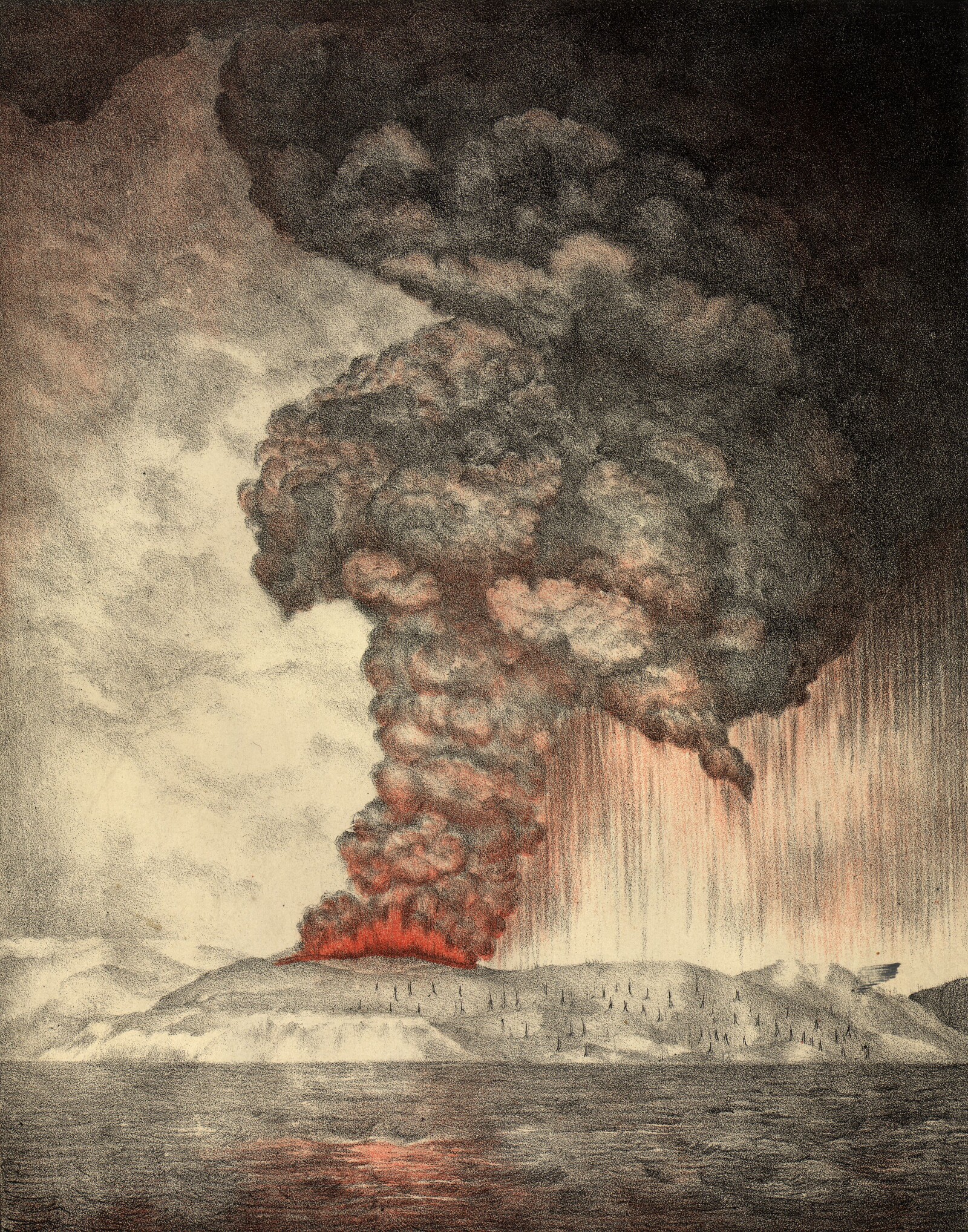

Enslaved Black people understood themselves apart from confinement, and given the brutality of plantation life, could see an epidemic as an escape. In 1869, when cholera ravaged the eastern portion of Cuba, a group of formerly enslaved insurgent maroons took the opportunity to burn down eighteen plantations.21 The insurgents targeted Spanish troops and the wealthy families from the eastern part of the island by setting fire to the plantations of Corestina, Resolucion, Santa Maria, and Doloritas. At the time, the plantation owners believed that some of the insurgents came from Trinidad. By the end of the pandemic, ten Cuban plantations ceased to exist. The uprising on these plantations were not only fueled by the conditions of confinement, but they were provoked by the simultaneous cholera outbreak. What this goes to show is how spatial arrangements can be conducive for pandemics to emerge, re-emerge, or even wither. Furthermore, what these slave revolts demonstrate is that illness is itself a symptom of violent confinement. Yet it also incubates the seed to escape—a liberation that is is not just spatial, but manifests through text.

The testimony of the enslaved show how they endured the violence of their enslavement on the one side and illness on the other, culminating in the idea of the plantation as incubator of resistance and liberation. By the end of her life, Harriet Jacobs paid little mind to the limits of her gender or race. To her, abolition was the only answer to a brutal system, while the other solution was death. In her autobiography she notes, “At least death frees the slave from his chain.”22 The back and forth between revolt and death was part of the logic of escaping contagion and confinement. While the plantation might be considered a planet without a suitable life support system, hardened by the abject condemnation of enslaved humans, the plantation is both a site of designed terror and resistance, the very kernel of liberation.

Harriet Jacobs, Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl (Boston: Penguin Books, 2000/1861).

Ibid., 98.

Peter Randolph, From Slave Cabin to the Pulpit. The Autobiography of Rev. Peter Randolph: The Southern Question Illustrated and Sketches of Slave Life (Boston: James H. Earle, 1893).

Ibid., 141.

Ibid., 141.

Ibid., 170.

US Census Tables, June 1, 1850, ➝.

“Die Cholera morbus, ihre Verbreitung und ihre Zufälle etc,” (Stuttgart: Universität Tübingen 1831); Schnurrer also wrote another opus, Chornik der Seuchen (1825), which documents the rise of epidemics more broadly. For more information about Friedrich Schurrer refer to, Dietlinde Goltz, “’Das Ist Eine Fatale Geschichte Für Unsern Medizinischen Verstand’: Pathogenese Und Therapie Der Cholera Um 1830,” Medizinhistorisches Journal 33, 3/4 (1998): 211–244.

Sandra Hempel, “John Snow,” The Lancet 381 (2013): 1269–1270.

Charles E. Rosenberg, The Cholera Years: The United States in 1832, 1849, and 1866, (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1987).

Deirdre Cooper Owens, Medical Bondage: Race, Gender, and the Origins of American Gynecology, (University of Georgia Press, 2017).

Dr. Collins, Practical Rules for the Management and Medical Treatment of Slaves, in the Sugar Colonies (London: Vernor and Hood, 1803).

James Ewell, The Planter’s and Mariner’s Medical Companion : Treating, According to the Most Successful Practice, I. The Diseases Common to Warm Climates and on Ship Board. II. Common Cases in Surgery, as Fractures, Dislocations, &c. &c. III. The Complaints Peculiar to Women and Children. To Which Are Subjoined, a Dispensatory, Shewing How to Prepare and Administer Family Medicines, and a Glossary, Giving an Explanation of Technical Terms (Philadelphia: John Bioren, 1807).

Dr. New, May 7, 1850.

Virginia Jayne Lacy and David Edwin Harrell, “Plantation Home Remedies: Medicinal Recipes from the Diaries or Jonn Pope,” Tennessee Historical Quarterly 22, 3 (1963): 259–265.

John C. Gunn, Gunn’s Domestic Medicine, or, Poor Man’s Friend, in the Hours of Affliction, Pain and Sickness: This Book Points out, in Plain Language Free from Doctors’ Terms, the Diseases of Men, Women, and Children, and the Latest and Most Approved Means Used in Their Cure, and Is Intended Expressly for the Benefit of Families in the Western and Southern States : It Also Contains Descriptions of the Medicinal Roots and Herbs of the Western and Southern Country, and How They Are to Be Used in the Cure of Diseases, Arranged on a New and Simple Plan, by Which the Practice of Medicine Is Reduced to Principles of Common Sense (Louisville: Charles Pool, 1838).

The New York Times, August 1, 1854.

Achille Mbembe, Necropolitics (Durham: Duke University Press, 2019).

Clifton Ellis and Rebecca Ginsburg, Cabin, Quarter, Plantation: Architecture and Landscapes of North American Slavery (New Haven: Yale University Press 2010).

The New York Times, February 6, 1869.

Jacobs, Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, 258

Sick Architecture is a collaboration between Beatriz Colomina, e-flux Architecture, CIVA Brussels, and the Princeton University Ph.D. Program in the History and Theory of Architecture, with the support of the Rapid Response David A. Gardner ’69 Magic Grant from the Humanities Council and the Program in Media and Modernity at Princeton University.