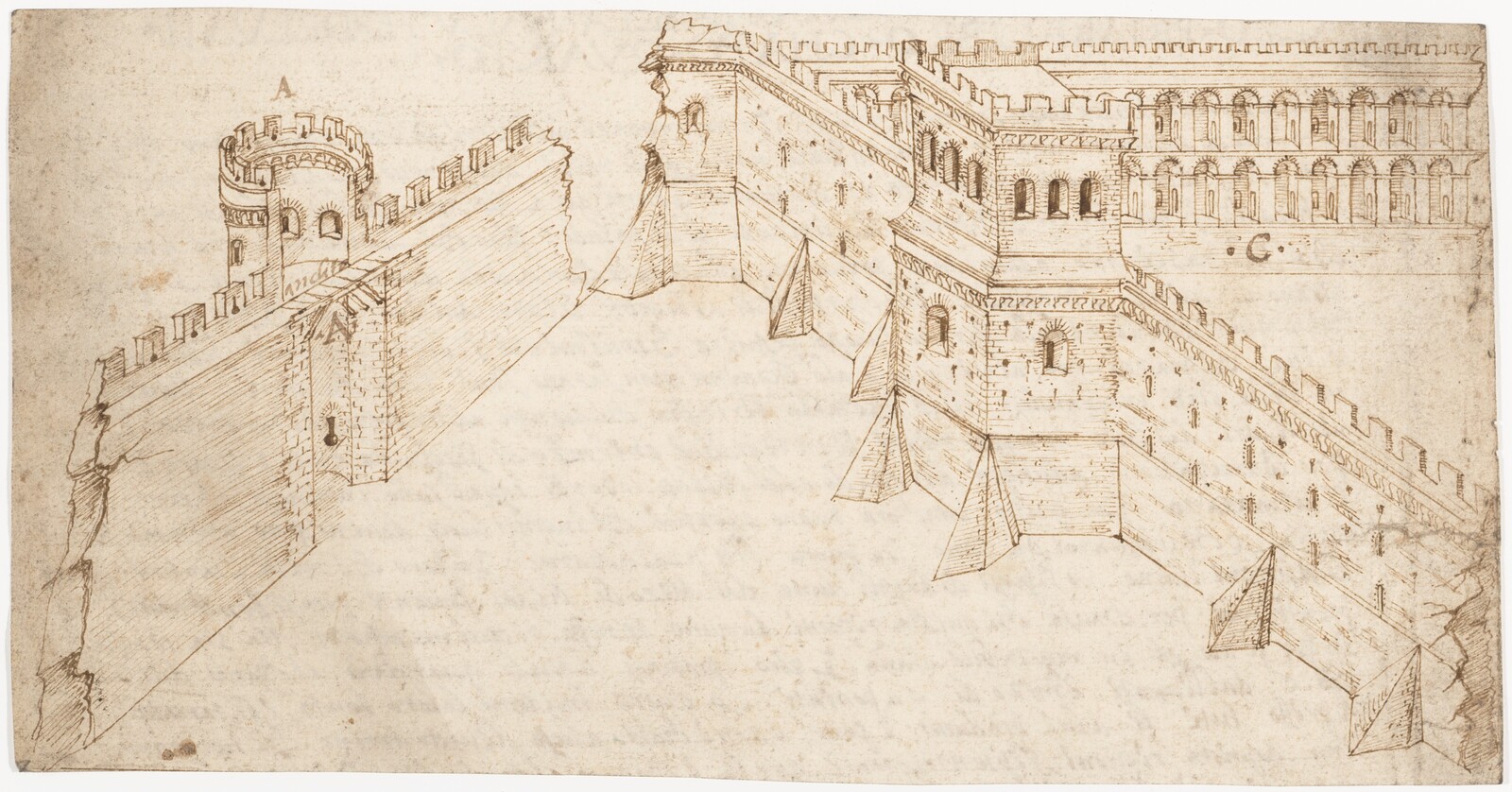

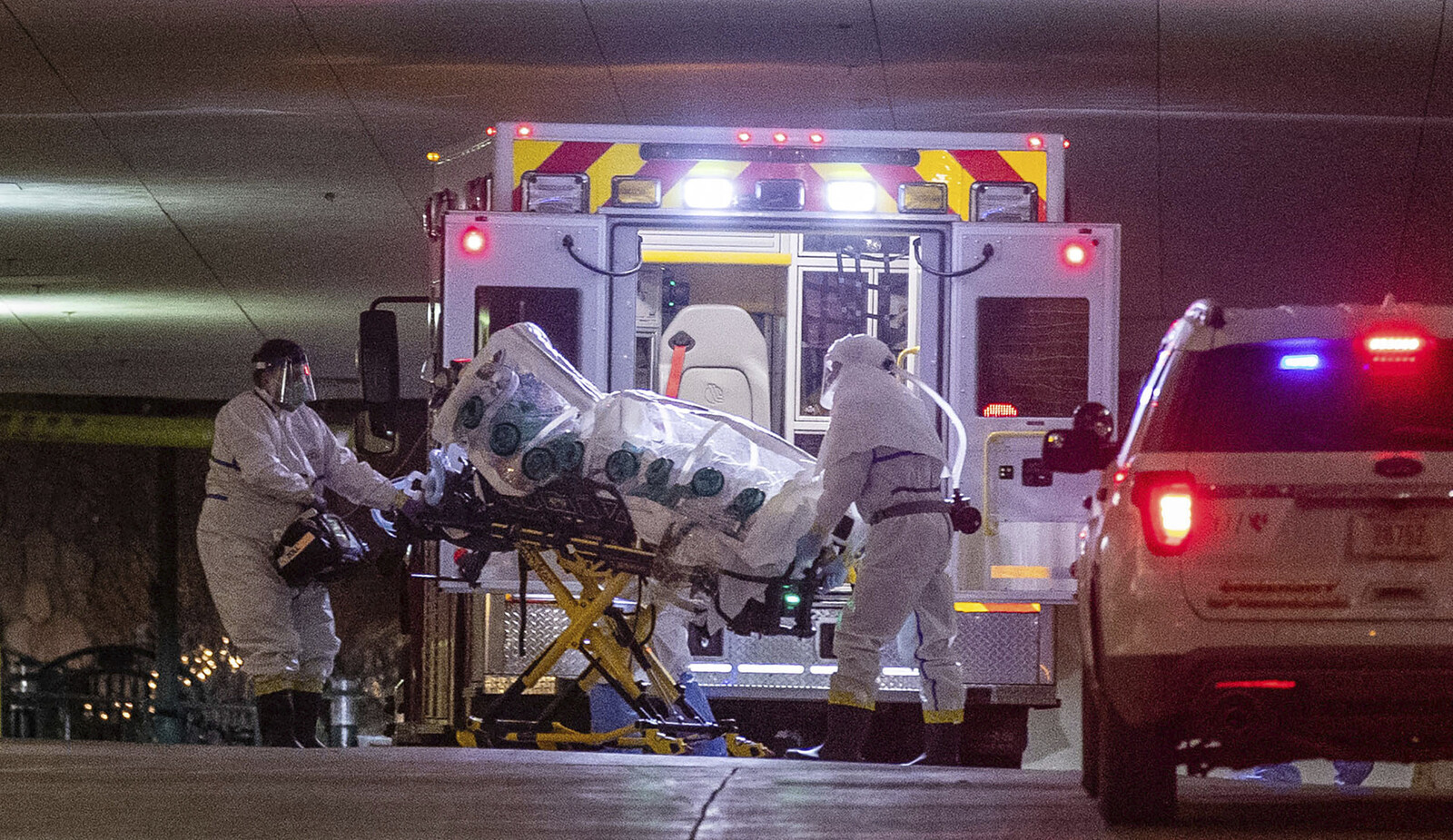

Every city, Vitruvius assumes in his first-century bce treatise On Architecture, needs walls.1 Deciding where to put them is the first thing to consider if you have the task of designing a city from the ground up. You don’t want the site to be too hot or too cold, too wet or too dry. Marshland usually teems with little creatures whose noxious breaths will waft over any fortifications you build, seeping pestilence into the bodies of the inhabitants. In his attention to these creaturely vectors, Vitruvius hints at a minor tradition for explaining disease transmission in ancient Greek and Roman authors, one that to our pandemic-weary sensibilities nevertheless feels familiar.2 But it is the vaguer idea of bad air that dominates the ancient accounts. In blurring the boundary between bodies to focus on the medium we share, these miasmatic theories call up equally familiar worries about the dangers of breathing as we track spiking levels of particulate matter via the Air Quality Index (AQI) and smoky haze. In any case, there are walls, and then there is the stubborn porosity of cities and bodies and the canniness of air. For a physician like Galen, who spent much of his life in Rome in the second century ce, bodies have to be cultivated according to an ethos of care that openly moralizes disease.3 For Vitruvius, what overwhelms our defenses should be avoided altogether.

In imaginatively building an ideal city in Plato’s Republic, written a few hundred years earlier, Plato’s protagonist Socrates takes up this project of building walls and fortifying bodies in the interest of regulating the circulation of affects (pathē) among citizens. The dialogue is notable for developing Plato’s theory of the tripartite soul, divided into the seat of desire and appetite; the “spirited” part, which Socrates likens to a dog, vicious or loyal depending on who it obeys and how you look at it; and reason. One of its guiding aims is the definition of justice. On the account that Socrates unfolds, justice depends on the rule of reason in the soul over the appetitive and spirited parts, and keeping reason on top will require, in turn, the policing of affect and desire, those intensities that feed its unruly partners. To see the argument clearly, he proposes translating it into a domain where it can be scaled up, like a font enlarged for the myopic reader. Enter the city as the soul’s macroscopic double. Like the soul, the city is iridescently complex; its health, on Socrates’ line of argument, depends on unity and coherence. But the city is not only an analogue to the soul. It is made up of people with souls of variable natures. These souls, like bodies, are porous, susceptible to the influx of affects through the channels of the senses and the body’s pleasures and pains. The psychic health of the individual is thus entangled with that of the city.

In short, the Republic is psychology doubling as political theory indebted to the doctor. The crafting and regulation of souls alongside bodies is the work of public health. To call this biopolitics registers the vast ambition of Plato’s “reason of the state,” as the early modern political theorist Giovanni Botero put it, in the Republic, while also recognizing the dialogue as ground—textual, imaginative, theoretical—worked over again and again alongside Aristotle’s Politics in the making of the modern European state and seeding the discourse of biopolitics in the twentieth century.4 But it also risks naturalizing the paradoxical and situated operation of a concept of nature in the dialogue and Socrates’ recursive, strategic recourse to the norm of health, appropriated from what had become the culturally dominant technē for the control of human nature in Athens by the early fourth century bce: medicine. Together with medical authors in this period, Plato is negotiating and improvising a concept of nature as at once self-legitimating and needy. In what will become a canonical passage from the Hippocratic Epidemics, nature is “untaught” and a model for the physician.5 At the same time, as Socrates says early in the Republic, it’s not enough for a body to be a body: it needs the medical technē because it is inherently unstable.6 In the same way, the city that is like a soul must be designed if it’s going to be healthy, and it needs constant care. There can be no naturalized nature in our reading of Plato, then; no uninterrogated bio- working together with a Greek origin story. In crafting human beings and a city for them to dwell in together in the Republic, Plato is experimenting with a concept of nature as an embodied norm, even as he uses it as the ground on which he builds.

In the Republic, things come down to the problem of difference. We humans are complex creatures, not only made up of two radically different parts, body and soul, but also, Socrates now proposes, divided in our souls, too. Moreover, we are different from one another “by nature,” so that the complexity of the human being is reproduced within the city, and in both cases according to a strict hierarchy of better and worse natures that at the macrocosmic level is formalized according to three political classes assigned different functions. But difference is only one side of the coin. The parts of the soul share life just as the inhabitants of the city do, and life, or at least terrestrial life, means interdependence and constant exchanges—of the matter we eat and the stuff of new life and the stories we tell. This traffic is made possible by what we hold in common. Yet if these exchanges aren’t tightly regulated by reason and its avatars in the state, Plato’s infamous philosopher-kings, they become pathological. Nevertheless, what’s important to remember is that there’s no avoiding the traffic in affect altogether: sympathy is a given.

The language of sympathy—more specifically, the Greek verb “to sympathize” (sumpaskhein)—enters our corpus of extant Greek texts with Plato, who uses it twice. The verb appears first in the Charmides.7 Socrates is observing that one of his interlocutors has “caught” his own aporia the way you catch a yawn. One person’s affect travels to another, and they “sympathize.” In fact, contagious yawning will figure prominently in the pseudo-Aristotelian Physical Problems, probably written a century later, in a book devoted to problems “about sympathy,” together with discussion about the standard contagious diseases in the Greek medico-philosophical tradition (diseases of the eyes and skin, tuberculosis) that evade the dominant humoral explanatory paradigms. Its appearance there suggests that a concept of sympathy took shape as a problem or puzzle implicated in questions of human nature of the kind that also drive the Republic’s twofold project of urban design and psychic regulation.

One of the apparent outliers in the pseudo-Aristotelian book about sympathy is the problem of why we suffer “in our mind” when we see someone in pain, being cut or tortured on the rack.8 In keeping with the speculative mode of the genre of “problems in nature,” the author proposes two possibilities. Either we’re impacted by effluences of that person’s pain, the way (he thinks) other kinds of perception work—in other words, material travels from the perceived body, enters through the eyes, and strikes the soul. Or we suffer because we have a nature in common, an idea that the author goes on to gloss as a kind of kinship (oikeiotēs). These possibilities look at least theoretically complementary. As David Hume puts it in his own account of sympathy, which helped shape the eighteenth century as the Age of Sympathy, you need both a relation of cause and effect “by which we are convinc’d of the reality of the passion, with which we sympathize” and “relations of resemblance and contiguity, in order to feel the sympathy in its full perfection.”9 But in presenting these hypotheses disjunctively, the Peripatetic author opens a window onto different angles on sympathy in the Republic, one oriented towards a nature held in common, and another towards the problematically porous boundaries of embodied life.. Although Plato only uses the verb “to sympathize” once, sympathy’s two facets can be seen in two key passages. By taking a closer look at both of these, we can better grasp the normative work performed by the healthy body as the paragon of complex unity in the dialogue and, precisely because of its complexity and entanglement in a mesh of relations, as the precarious object of technical control. In short, through sympathy, the body politic is imagined to be both an organic whole and a breeding ground for contagious affect.

We can start with the second use of the verb “to sympathize” in Plato, which appears in Book 10 of the Republic. Earlier, in Books 2 and 3, Socrates had launched his infamous critique of the poetry that dominated education at Athens, especially Homer and Hesiod. Storytelling is the state’s most powerful tool of social control in the Republic, capable of literally molding souls. It must therefore be used with considerable care. Socrates’ attack on the poets in Book 3 especially targets the long-term psychic risks to the future elite of habitually molding themselves into characters rocked by disease or love. But Socrates is wary, too, of the very lability of the mimetic self, the shape-shifting of the poet and the performer.10 In Book 10, Socrates turns his focus to the dangers posed to the unified soul not by acting but by tragic spectatorship.

Socrates and his interlocutor Glaucon start off agreeing that the person whose soul is in order would never give in to excessive grief and lamentation, no matter how great the loss. But even the best of us, Socrates says, find that the rational soul relaxes its grip on the appetitive soul’s desire for lamentation when we watch the sufferings of others on stage. We find that we happily surrender ourselves to the performative grief of tragic heroes, “suffering along with the characters as we follow.”11 Socrates pathologizes this “strong pity” as the stimulation of the part of the soul that takes pleasure in emotion and that, prone to excess, is always at risk of overwhelming the rule of reason. Being laid open to another’s suffering makes the tragic spectator more susceptible to losing control of himself in the face of his own powerful emotions (pathē). Being exposed to the suffering of others in the theater, Socrates says, “infects” our affective life outside the theater. The very passivity of the process induces states that define pathology for Plato: femininity and enslavement.12 Here, then, the audience’s compulsive “sympathizing” with tragic heroes is diagnosed as the problem at the root of the genre’s threat to psychic unity. Like the effluences of pain in the pseudo-Aristotelian Problems, the affects of othered others on stage enter the soul or mind through the senses and compels a response. But the identification of the (once rational) spectator with the (othered) performer produced by sympathy comes at the cost of psychic disruption and, in so doing, seeds division in the city. The only option, Socrates says, is to exile tragedy.

If tragedy produces a divisive sympathy, another kind of sympathy exemplifies unity for Plato. To understand its work, we have to back up to Book 5, midway through the dialogue, to a point where Socrates is trying to wrap up his account of the ideal city and shift into a detailed description of the various pathologies to which it is eventually destined to succumb. At this point Glaucon interrupts to point out that he’s failed to say anything about a critical part of any city, the family: sexual reproduction, women, children. Glaucon’s request spurs Socrates to describe another famous part of his proposal for the ideal city comprising, first, the admission of women to the ranks of the guardians by way of the same educational regimen assigned to the class of boys working towards the apex of the socio-political hierarchy and, second, the abolition of the family, to be replaced by political kinship.

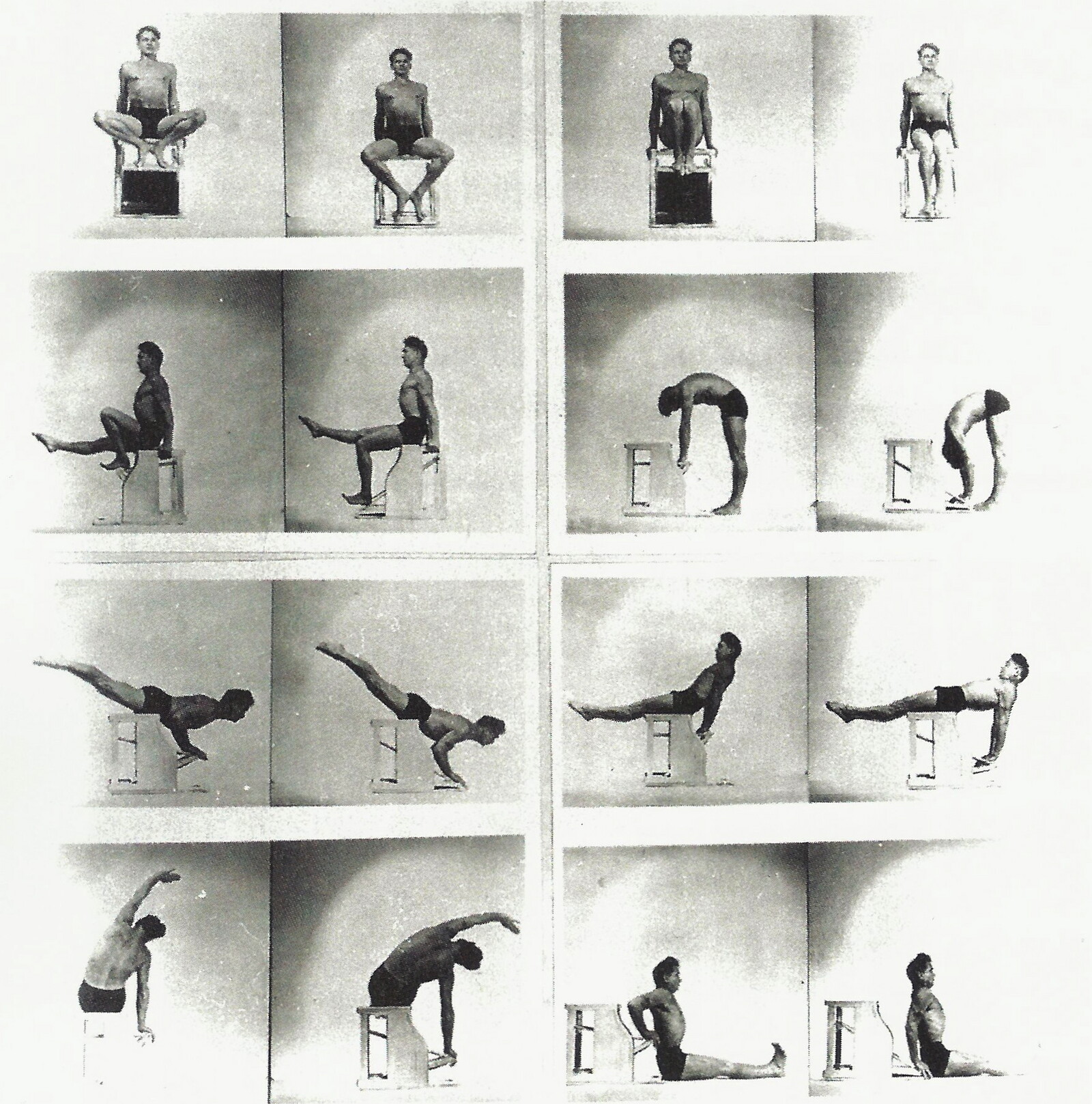

The two policies go hand in hand as outcomes of Socrates’ account of nature here. Part of what is radical about his plan is that it is built on the admission that some women have the natures to be guardians, rather than artisans or “producers.” The hierarchical difference in natural capacity is thus reconfigured in terms of class, rather than sex. But nature isn’t sufficiently trustworthy to ensure the trans-generational reproduction of difference along these lines. Eros is messy.13 Sexual reproduction is messy. The city planner has to step in to stave off anarchy. And so Socrates proposes a eugenics program of shocking proportions, explicitly modeled on animal breeding.14 We know from Socrates’ account of education in Book 3 that the rulers are constantly surveilling the young to determine which of those assigned to the guardian class are fit to become rulers, while also keeping an eye out for those whose births would predict a lower class, but who demonstrate “natural” excellence.15 This design work also entails grouping guardian men with women of similar natures through co-ed education and coercing them to mate according to city-sponsored marriage rituals.16 At the same time, Socrates wants to thwart the formation of kinship within the genealogical family in order to form the city as the only natural community.

Babies are thus whisked away at birth to an institutional nursery to become wards of the state. Their removal begins anew the twin processes of care and surveillance under the watchful eye of the rulers while denying any naturalness to the parent-child bond in the interest of naturalizing civic kinship.17 Meanwhile, we have learned in Book 3 that everyone will be told that their memories of their childhood and education were only dreams. Experience is to be replaced with a “noble lie,” the myth of metals, that legitimates class assignments in terms of the citizens’ inborn natures and casts the city as a family.18 All citizens, according to the myth, are earthborn kin, born to defend their motherland and love their brothers and sisters. But their souls are divinely fabricated out of different metals (gold, silver, bronze, or iron) that ostensibly dictate their position in the city’s hierarchy. In the realm of desire and sexual reproduction, then, Socrates faces a dynamics of mixture and a logic of natural community that he cannot exile. He can only try to engineer things and to engineer, as well, like a “brave doctor,” a story that masks the manufacture of an unequal social order qua family with the face of nature, understood to govern both sameness and difference.19

Much could be said about Socrates’ proposals. Here I only want to point to the test he uses in Book 5 to determine if the technical production of kinship has succeeded in making a healthy body politic. If the work is successful, the whole city will be united in its experience of pleasure and pain, as is the case, Socrates says, in a living being. If the finger is wounded, “the entire community stretching through the body to the soul in one system of control senses it, and this entire community suffers in pain together with the affected finger, as a whole.”20 The experience of suffering—and feeling pleasure—together thus bears witness to the city as a natural unity structured by hierarchy. In Book 10, pains and pleasures and desires are dangerous because they defy reason’s control. But here it is precisely because pain is unwilled that it is such a compelling sign of the unity of the citizen body, one that proves the success of technē in stabilizing and manufacturing nature even as the “natural” living body supplies the paragon of the complex One. The sign of shared affect enables Plato to name its cause as the relationship itself, and, more specifically, the relationships that make up the tissue of the city according to mythically naturalized hierarchies of power.

Plato does not use the language of sympathy in this case. But in looking to vitalist unity as its cause, he lays the groundwork for what will become a classic argument from sympathy for the Stoics, who were close readers of Plato. A couple of centuries later, the Stoics deploy the alleged fact that the whole body sympathizes with the injured finger as proof that the body is unified, going on to argue that the entire cosmos is unified on the basis of its evident “sympathies” (e.g., the moon’s production of the tides, seasonal change, climactic events).21 It is cosmological sympathy that underwrites the Stoic theory of world citizenship—that is, cosmopolitanism, the theory of the kosmopolitēs. Already in the Peripatetic Problems, the nature held in common is not limited to members of the city but, in becoming synonymous with human nature, is imagined to produce universal kinship. This idea that sympathy manifests a “natural” kinship among all human beings is taken up by the Hellenistic historiographers, most notably by Polybius, who is trying to make sense of political communities devastated and restructured by Rome’s violent imperial expansion in Stoicizing terms that experiment with a self-consciously post-democratic imaginary.

The city that Plato designs is decidedly not a democracy. But it, too, is haunted by democratic politics. In Book 8, Socrates offers an anxious critique of democracy as a mess of promiscuous freedom where “those who have been bought as slaves—whether male or female—are no less free than those who bought them” and the relationship of men and women is marked by excessive equality (isonomia).22 On Plato’s diagnosis of democracy’s ostensible pathologies, freedom would seem to spawn an epidemic of boundary collapse. The snowballing of affect is fed by tragedy: in the Laws, Plato offers the neologism “theatrocracy” (theatrokratia) as a synonym for democracy and its supposedly excessive liberties (although, on Luce Irigaray’s classic critique, he puts scenography to his own uses in the Republic’s famous myth of the cave). It eventually leads to the rule of the tyrant, who is the embodiment of appetitive soul.23 Plato’s aversion to democracy was seen in the wake of the second World War as evidence of his totalitarian inclinations, most famously by Karl Popper. The reading of Plato’s Republic as the Ur-antidemocratic text has been elaborated more recently by, among others, Jacques Rancière, who uses Socrates’ investment in “natural” hierarchy and anti-Athenian stance in the Republic to theorize democracy as an order that refuses foundational order (archē) and, more specifically, any order founded in the “nature” of kinship.24 Mika Ojakangas has positioned Plato’s Republic as an origin point for Western biopolitics.25

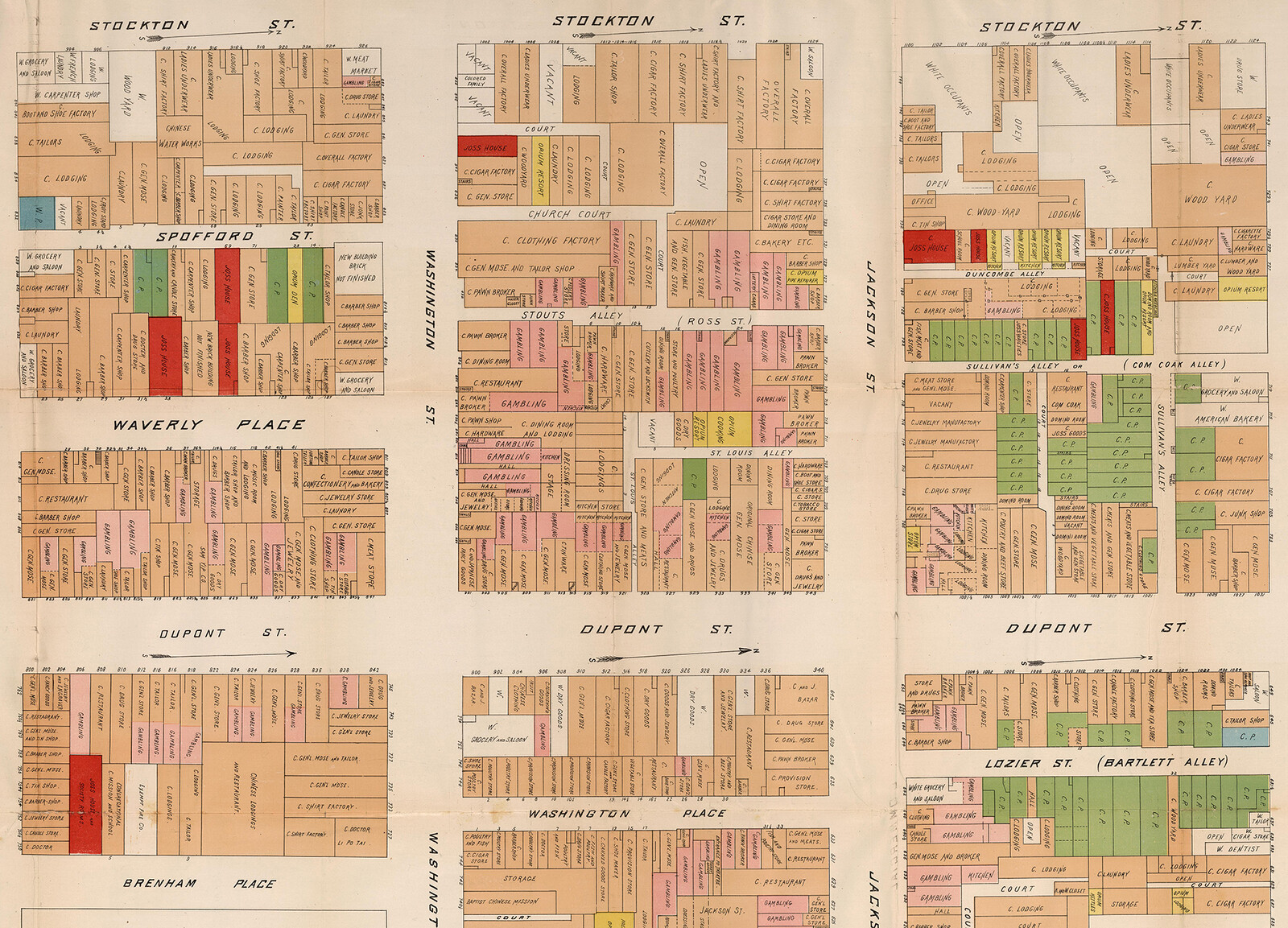

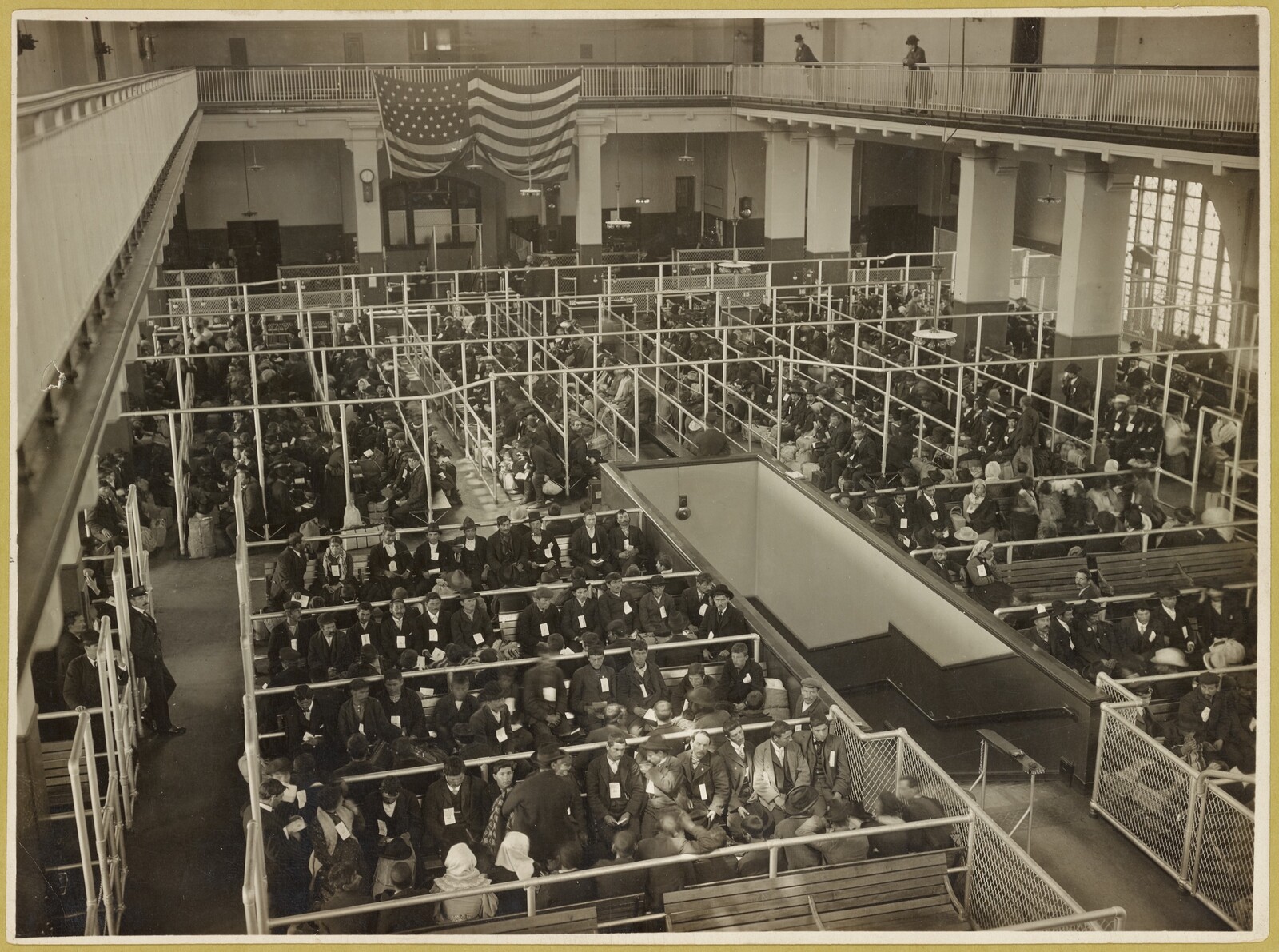

But Plato’s faith in nature is not so straightforward. Demetra Kasimis has argued that, in using the text to theorize the democratic ideal by way of a foil, Rancière prematurely reduces the dialogue to its investment in “natural” hierarchy and order rather than seeing it, too, as “revelatory of hierarchy’s various iterations, machinations, and indeterminate effects” in democracy, too.26 By extracting democracy as an ideal thrown into relief by Plato’s engineered regime of reason, Rancière neglects the material conditions of its construction and the dialogue’s own frame: the historical Athens of the late fifth and early fourth centuries bce on whose outskirts the dialogue takes place, in the house of a wealthy metic, that is, an immigrant with no path to citizenship for himself or his children. Plato’s Athens was a birth-based democracy legitimated by the myth of autochthony.27 It took definitive shape through anti-elite measures—including a law instituted by Pericles in 458 bce that required both parents be citizens for citizenship—that unfolded in tandem with ideologies of race shaped by theories of the body and human nature as objects of expert knowledge, technical control, and care moralized by anxieties around gender, class, and sovereignty in the late fifth century.28 On Kasimis’ reading, Plato’s myth of metals carries a subversive critique of Athens’ own noble lie that its citizens were born from the earth into a natural brotherhood. It is democracy’s very investment in kinship to secure identity and political membership, rather than a disavowal of naturalized (both given and valued/abjected) categories of the human, that produces the “status trouble” Plato identifies but does not invent.29

In situating the dialogue as a text written in fourth-century bce Athens, Kasimis is not registering a historicist’s correction to the use of the text for the ends of political theory. Rather, she targets the “theoretical toll” exacted by the text’s decontextualization: the risk of getting swept along with Plato’s project of disciplining the messiness of “nature” into social stratification legitimated by nature restored as myth; of mistaking Plato’s work of abstracting order through the manipulation of bodies and souls for binaries that are set in stone at the foundations of Western political theory and metaphysics.30 After all, Plato’s production of nature as myth does not cover its tracks in the dialogue itself. Nor is Athens in its practices of exclusion absent from the scene. Not to mark these traces is to leave alone, too, the figure of the Greeks as mythic origin—of philosophy, of politics, of biopolitics. It is to assume its classical life rather than make of these much-trafficked texts a “nourishing food,” as Andrés Henao Castro proposes to do in his recent rereading of Antigone, imagining Sophocles’ play as the corpse of Polyneices cast to the birds, and, in so doing, disperse them anew to noncanonical places.31

At the same time, when we equate the work of demystification with the critique of naturalization, the very figure of nature paradoxically becomes naturalized. It is true that Plato has Socrates build an elaborate process of surveilling and correcting nature into the design of his city. But does that mean he gives up on the promise that nature offers—that is, the promise of a norm outside of convention—to the very premise of ideality in the dialogue in the guise of health? It is a promise that Plato takes over from a robust cosmological and anthropological debate in fifth- and fourth-century bce Athens, “the inquiry into nature,” as he has Socrates call it in his famous intellectual autobiography in the Phaedo.32 It is this tradition that generates a text like the Peripatetic Physical Problems. But nature in the Phaedo is no ally. Socrates famously attacks the “physicists” for their radical materialism—their care only for bodies and powers (hot, cold, wet, dry), their failure to encode value into the non-human world and put a god in charge—in a scene that becomes iconic in Platonism as it is elaborated historically as a practice of reading truth into a corpus of authoritative texts that is itself part of a culturally synthetic and nomadic cosmological tradition organized by Nature and branded as Greek in the last centuries bce and first centuries ce. What Socrates wants is a cosmology that restores the Good to a primary cause.

Socrates’ desire is addressed by Plato’s cosmological epic, the Timaeus. The dialogue was probably written years after the Republic. But its narrative frame positions it as a sequel, where the failures of politics practiced by embodied mortals are subsumed into a cosmos whose own life is miraculously inviolable (the dialogue’s narrator describes a cosmic animal that sustains itself in a perfect affective cycle of auto-stimulation). In the account of world creation in the Timaeus, nature is largely absent and aligned with materialist causes that have been reassuringly subordinated to mind, reason, and divine providence. And yet, its disciplining effects strategically surface in the dialogue, as they do in the Republic, as ways of being in the world for specific kinds of things that are legitimated or not through being “according to nature” (kata phusin) or “against nature” (para phusin). And in fact, the normative force of nature in the adverbial position is as much a part of the cosmological-anthropological idiom that Plato is working within as the materialists’ rubric of bodies and powers. Pace Socrates in the Phaedo, ethics was never absent from this idiom. Where a cosmology of nature meets an account of human nature in the fifth century bce under the pressures of an imperial, enslaving democracy’s fixation on masculinized self-control, it crystallizes in terms of health and disease as both objects of control within a technē of medicine and as the ostensibly given norms that guide the physician’s work. The ethical imperative to the citizen to control his own material being—and the traffic in affects it lives through—comes to define the autarchy supposedly given to the Athenian as his birthright, but in practice requiring surveillance and manipulation. In Book 3 of the Republic, Plato bears witness to the success of naturalizing medicine in this period as a regulatory (and self-regulatory) regime at Athens and has Socrates frankly state his interest in appropriating its vast market share for philosophy’s techniques of psychic control.33 At the same time, the very proliferation of these regulatory regimes bears witness to a conceptualization of nature as animated by an elusive, non-human, ludic motility, what Emanuela Bianchi has called the queer performativity of ancient phusis.34

My point here is that part of the work of situating the Republic for political theory and, above all, for biopolitical theory, needs to be understanding “naturalization” itself as a polymorphous, culturally embedded, politically consequential process that persistently entangles Socrates in his efforts to imagine otherwise in ways we may read as symptomatic of the limits of Plato’s grasp on human flourishing, or the depth of his critical apparatus, or theory’s historical conditions—or all three. The two sides of sympathy traverse the topology of a historically medicalized body mapped by Socrates onto the tripartite soul and then blown up to the size of a city: on the one hand, health as complex unity sustained through the regulation of affects by an inherent force of order (i.e., “nature”); on the other hand, embodiment in the physical world as a condition of precarity and porosity requiring the technical control of bodies and communities if a politics practiced by self-sovereign (not femininized, not enslaved) citizens is to be possible, at least until the moment that collapse is unavoidable.35 After all, cities, like humans, are mortal by definition.

But the situating work that I’m advocating for here doesn’t mean a particularism designed to correct abstraction. As much as it invites an interrogation of a text’s conditions, it also experiments with sense-making as conditioned by the present and practiced collectively. I say “experiment” to get at the work of reading the Republic as imbricated in the many different histories of reading Plato that for all their differences cannot not mythologize him, and the Greeks, and so can only show the seams, laying bare the decisions as well as the fact that decisions always get made when you craft something. That’s arguably what Plato has Socrates doing in the Republic: showing the seams of a made object. Still, it doesn’t mean that Plato gives up on nature, for better or for worse, as one name of something in embodied humans that shapes their capacities to live or die, thrive or suffer. The question, rather, is how to bridge a gap between nature as the non-human materiality of the self that is untransparent to embodied human beings and nature as norm in the form of an adverbial phrase (kata phusin, para phusin) that governs an evaluation, usually consequential, of whether a life is being lived “well,” or not—and of whether a political community is thriving, or an aesthetics of collective life, or a planet.

That question transmutes but also tenaciously recurs across communities that have made sense of their shared world in terms of nature. One challenge is to make sense of this situated seriality in terms that resist the dazzling analogy of the living being whose parts are integrated into a unified whole according to a master trope of health. Different nineteenth- and twentieth-century regimes of biopolitics in the US and Europe have taken a Greek origin and norm as foundational to their own claims on health and racialized practices of exclusion. But reifications like “the classical tradition” and “the West” also risk a less flagrant trust in vitalist unity, not least because the embedded, interested practices of reading texts like Plato’s Republic have so often conditioned the imagination of political community, its relationship to life, and its failures in these cultures. To show the seams is not simply to work through nature as made in the fifth and fourth centuries. It’s to show the Greeks as made over and again, entangled in the making of the ethics and aesthetics and politics of health that inform the diagnoses of crises of public health, democratic politics, racial capitalism, and ecological collapse currently circulating, neither inside nor outside biopolitics.36

Caught in this mesh, what I make of the two sides of sympathy in the Republic is an exercise in conceptualizing the difficult, provisional, and social practice of care in the face of so much suffering. In the US right now, it has become easier to see how the work of nativism—of race and gender, ableism and power—in democratic politics and in democratic erosion around the world goes hand in hand with a logic of roots. But Plato’s recourse to the model of a body integrated in its parts in his work of figuring political kinship in the Republic also invites scrutiny of what we think is at stake in saying a community or a country or a world is broken or divided or sick.

The Socrates of the Republic places tragedy at the heart of his diagnosis of the ills of democratic Athens, aligning its effects with the power of what he sees as feminized and enslaved within every human being. The extant tragedies are themselves caught in this cultural logic of power and abjection. But they are also provocative in the ways they stage the gap between suffering and the capacity to make sense of it. In that gap, characters often fail to come together. As a historical form, tragedy is cultivated under conditions of hyper-investment in law and medicine as domains for regulating collective life according to the logic of blame and cure, and the plays repeatedly enact a commitment to marking the limits of that logic. In this sense extant tragedies work like aesthetic technologies for experimenting in public, by means of a highly formalized but repeatedly decentered perspectival fluidity, with the utopian possibilities and the provisionality and the limits of the stories that people generate to sustain political life in the face of human suffering. They hold onto a space between acknowledging harm and the need for care without settling on a regime of health.

That refusal to settle haunts the Republic in its quest for psychic and political flourishing. Plato, it seems to me, reads tragedy as another form of materialism, and rightly, albeit through the lens of a constricting, often paranoid anti-materialism. But like many tragedies, the Republic shows the seams of making an aesthetics of shared life in a political community. And so, too, it helps us see the seams of what we call philosophy, and art, and politics, and history, and architecture as always situated, porous, transitioning practices of collective survival that cannot and should not try to cage what they want to sustain and, in that failure, remain necessary to its persistence.

Vitruvius, On Architecture 1.4.1–1.4.6.

See also Varro, On Agriculture 1.12.2–1.12.4, who imagines tiny animalia being actually inhaled, with Vivian Nutton, “The Seeds of Disease: An Explanation of Contagion and Infection from the Greeks to the Renaissance,” Medical History 27 (1983): 1–34, esp. 11 on Varro.

Galen has an ambivalent relationship to a theory of contagion precisely because it undermines his moralizing: see Nutton, “Seeds of Disease,” 15–16 and Brooke Holmes, “Galen on the Chances of Life,” in Victoria Wohl ed., Eikos: Probabilities, Hypotheticals, and Couterfactuals in Ancient Greek Thought (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014), 230–250, esp. 242–247.

For both periods—early modern and twentieth century— in relationship to ancient Greek political theory, see Chiara Bottici, “Rethinking the Biopolitical Turn: From the Thanatological to the Geneapolitical Paradigm,” Graduate Faculty Philosophy Journal 56 (2015), 175–197, 178 with nn. 17–18 on Botero; and below, n. 36 on bios and biopolitics.

(Hippocrates) Epidemics VI 5.1.

Plato, Republic 1, 341e.

Pl. Charm. 169c. The dialogue is generally placed in Plato’s earlier “Socratic” period before the Republic.

(Arist.) Phys. Probl. 7.7. On the conceptualization of this problem as a “natural” problem in the book, see Brooke Holmes, “Pain, Power, and Human Community: Empathy as a ‘Physical Problem’ in Pseudo-Aristotle and Beyond,” in Katherine L. Hsu, David Schur, and Brian Sowers eds., The Body Unbound: Literary Approaches to the Classical Corpus, 13–56 (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2021), where I also examine the implications of seeing the person in pain as enslaved (judicial torture being limited to enslaved persons at Athens).

Hume 1978: 320, cited at Sayre-McCord 2015: 215n.8.

Pl. Rep. 3, 395c–395e, 396c–396e, 397a–398a.

Pl. Rep. 10, 605d4. On the mixed pleasure and pain of watching tragedy, cf. Pl. Phlb. 48a.

On the dangers of mimesis for Plato, see Rep. 3, 394e–396e; Laws 7, 814e–817a, with Stephen Halliwell, The Aesthetics of Mimesis: Ancient Texts and Modern Problems (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2002), esp. 72–97. In the Laws, Plato delegates the mimesis of base characters to the enslaved or metics: no free person is allowed to train in such forms of representation (Laws 7, 816e). The entanglement of mimesis and enslavement continues through the Roman period. On forced performance as a site for the exercise of domination over the enslaved in the American context, see Saidiya V. Hartman, Scenes of Subjection: Terror, Slavery, and Self-Making in Nineteenth-Century America (New York: Oxford University Press, 1997), esp. 17–78.

See esp. Plato, Republic 5, 458d–458e.

Plato, Republic 5, 459a–459b, 460d on infanticide.

Republic 3, 412e–414c.

Plato, Republic 5, 459d–459e–460b. The men who display the best natures are rewarded with sexual access to many women in the interest of increasing their offspring (see also 468c).

See Plato, Republic 5, 461d–461e, on precautions against incest that reconfigure the parent-child bond.

Plato, Republic 3, 414b–415c, 416e–417a.

Plato, Republic 5, 459d reintroduces the idea of the lie as medicine used by a brave (literally: masculine) doctor.

Plato, Republic 5, 462d; cf. 464a–464b. The idea that the whole body feels the pain of the smallest part appears in a medical text from the early fourth century: (Hippocrates) On Places in a Human Being 1.

Sextus Empiricus, Against the Professors 9.78. The attention to the pain of the finger as implicated in the experience of the whole points to the flat ontology produced by cosmological sympathy in the Stoics, which exists in tension with the hierarchy of a scala naturae, much as already in the Republic, nature is both common and hierarchical. See further, Brooke Holmes, “On Stoic Sympathy: Cosmbiology and the Life of Nature,” in Emanuela Bianchi, Sara Brill, and Brooke Holmes (eds.), Antiquities beyond Humanism, 239–270 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2019).

Plato, Republic 8, 562e–563b.

Plato, Laws 3, 701a; Luce Irigaray, Speculum of the Other Woman, trans. G. C. Gill (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1985).

Jacques Rancière, The Hatred of Democracy, trans. Steve Corcoran (London: Verso, 2006), 40–41.

Mika Ojakangas, On the Greek Origins of Biopolitics: A Reinterpretation of the History of Biopower (New York: Routledge, 2016).

Demetra Kasimis, The Perpetual Immigrant and the Limits of Athenian Democracy (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018), 116. Kasimis is also critically engaging Arlene Saxonhouse’s rich and provocative reading of Book 8, which singles out the fluidity of identity categories in democracy as the primary target of Socrates’ attack: Arlene Saxonhouse, “Democracy, Equality, and Eidē: A Radical View from Book 8 of Plato’s Republic,” American Political Science Review 92.2 (1998), 273–283.

Nicole Loraux, The Children of Athena: Athenian Ideas about Citizenship and the Division between the Sexes, trans. C. Levine (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1993).

See esp. Susan Lape, Race and Citizen Identity in the Classical Athenian Democracy (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010).

Kasimis, Perpetual Immigrant, 95–96, 129–131.

Ibid. 119.

Andrés Henao Castro, Antigone in the Americas: Democracy, Sexuality, and Death in the Settler Colonial Present (Albany: State University of New York Press, 2021), 17.

Plato, Phaedo 96a–99c.

Plato, Republic 3, 407a–408a.

Emanuela Bianchi, “Nature Trouble: Ancient Physis and Queer Performativity,” in Emanuela Bianchi, Sara Brill, and Brooke Holmes eds., Antiquities beyond Humanism, 211–238 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2019), esp. 228–236.

There are also important disanalogies between soul and body that mark the limits of the health/disease model for an account of justice, virtue, and vice that I cannot discuss here. See further Sara Brill, Plato on the Limits of Human Life (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2013), esp. 111–114, on the Republic, and on the shifting terms of the medical analogy in Plato, Brooke Holmes, “Body, Soul and the Medical Analogy in Plato,” in J. Peter Euben and Karen Bassi (eds.), When Worlds Elide: Classics, Politics, Culture, 345-85. Lanham, Md.: Rowman & Littlefield, 2010.

On the bios of biopolitics and the Greeks, see Brooke Holmes, “Bios,” Political Concepts: A Critical Lexicon 5 (2019), ➝.

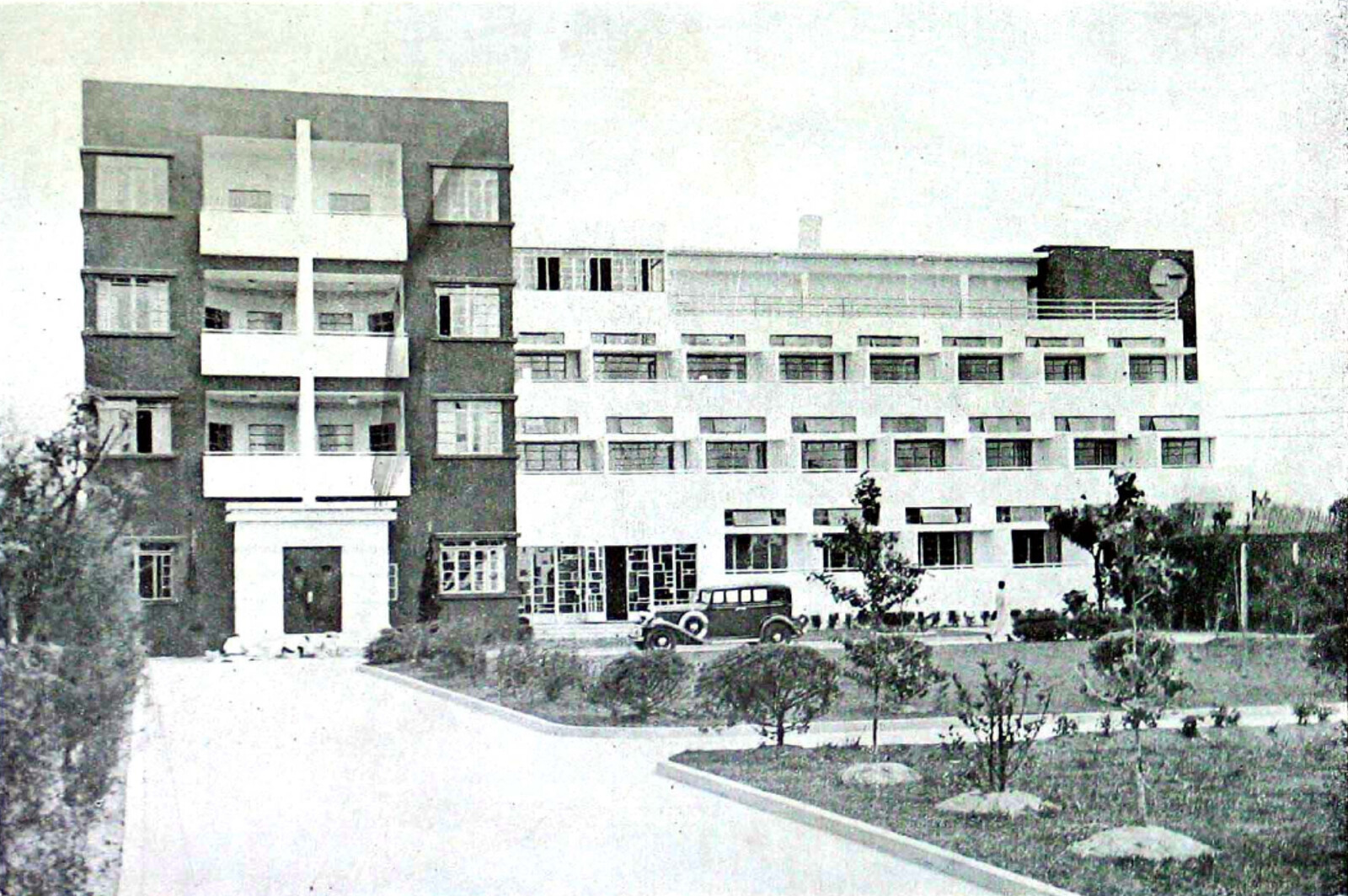

Sick Architecture is a collaboration between Beatriz Colomina, e-flux Architecture, CIVA Brussels, and the Princeton University Ph.D. Program in the History and Theory of Architecture, with the support of the Rapid Response David A. Gardner ’69 Magic Grant from the Humanities Council and the Program in Media and Modernity at Princeton University.

Category

Subject

For superb feedback, editing, and encouragement on this essay, I am very grateful to Nick Axel, Beatriz Colomina, Demetra Kasimis, Karan Mahajan, Tony Vidler, and Mark Wigley.