Le doy fuego a la Fortaleza como se supone

Y al otro día voy a la iglesia pa’ que me perdonen

Mejor no quieras probar de qué estamos hechos

Aquí en El Monte heredamos el mismo pecho

Tus disculpas se ahogan con el agua de la lluvia

En las casas que todavía no tienen techoI set La Fortaleza on fire as I should

And the next day I go to church to be forgiven

You don’t want to test what we’re made of

Here in El Monte we’ve inherited the same heart [we are all family in Puerto Rico]

Your apologies are drowned with rainwater

In houses that still don’t have a roof—Residente in Residente, iLe & Bad Bunny, “Afilando Los Cuchillos” (“Sharpening the Knives”)1

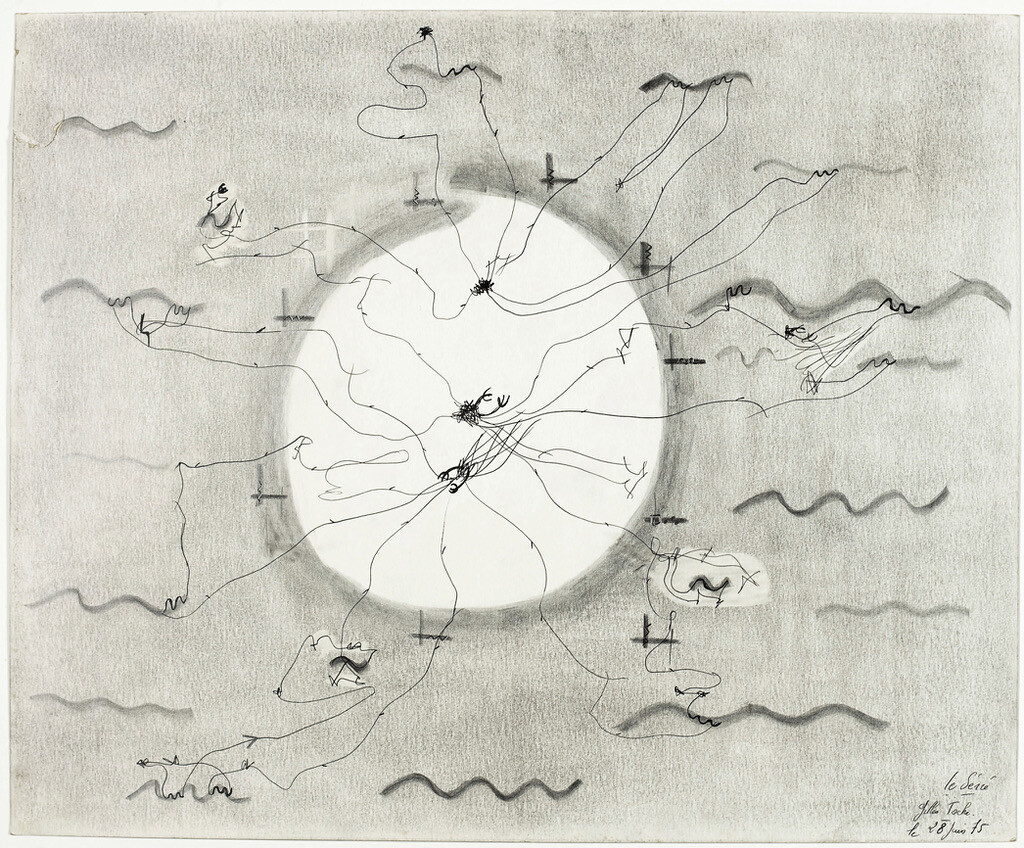

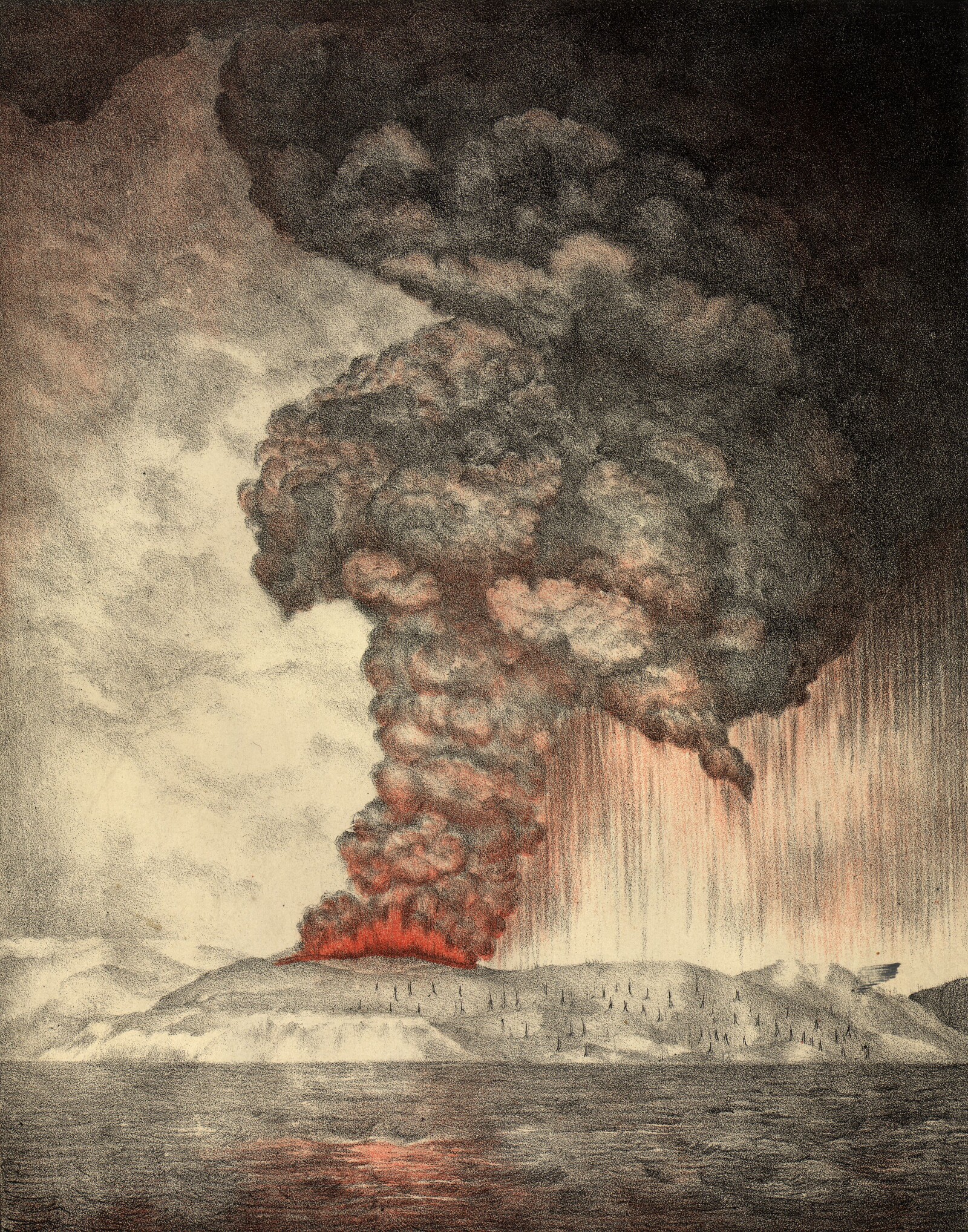

Houses without walls or rooves. Houses filled with plants and rainwater. Houses reduced to rubble and ash. For the Puerto Rican home, the boundary between nature and architecture is permeable and precarious. When the boundary is controlled—opening a window to let the breeze in, placing a rocking chair in a covered patio’s shade—it seems as if the built and natural environments are collaborating, assisting one another. But when the balance is tipped from either side, recovery can be long and difficult.

In the last five years, the frequency and intensity of natural disasters have increased dramatically across the Puerto Rican archipelago. In 2017, Hurricanes Maria and Irma tore the rooves from homes and wreaked havoc on roads, power lines, and other essential infrastructure. Then, two years later, while Puerto Ricans were still entrenched in the process of mourning losses and rebuilding a sense of home, leaked text messages between government officials revealed gross neglect and disrespect towards women, queer people, and lives lost in the hurricane and its wake. Boricuas (Puerto Ricans) were fed up. They took to the streets and, after fifteen days of mass protests, forced the then-governor Ricky Rosselló to resign.2 Only a few months later, a series of disastrous earthquakes caused yet more destruction on the main island’s southern coast.

While forces of nature were threatening working people’s houses and safety, real estate developers bought up property along the coasts and began to build luxury condos and resorts, taking advantage of low property costs and tax breaks for US citizens. Rincón, for example, a popular destination for surfing on the northwest coast of the main island, made the news last year when private investors began to construct a pool on a public beach, even though a previous pool and an entire apartment complex had been destroyed by the tides of Maria.3 Despite the known consequences of beach erosion and wildlife endangerment, the construction was approved by the government. When it came to the benefit of tourists and the moneyed elite, architectural development trumped local concerns about the natural environment, with police and security guards protecting property over people. Protestors gathered to oppose the project, and it eventually was halted.

Locals, then and now, face the double task of struggling to rebuild for themselves after nature has struck and resisting construction for tourists that would actively harm the environment. There are so many examples of a tipped “balance” between nature and architecture in Puerto Rico (and in the Caribbean at large) that the idea of a stable equilibrium between the two is not just naïve but delusional. Furthermore, it contributes to the doctored image of a tropical paradise that is ceaselessly fed to tourists and investors, even—or perhaps especially—in times of crisis. What happens if we do away with the utopian promise of a fixed equilibrium, of a controlled homeostasis? Rather than perpetuate some paradisical standard, which ignores centuries of colonial exploitation and the dependencies that it has forced into place, we should consider the Puerto Rican home—from the individual house to the archipelago at large—to be immunocompromised.

Casa Klumb

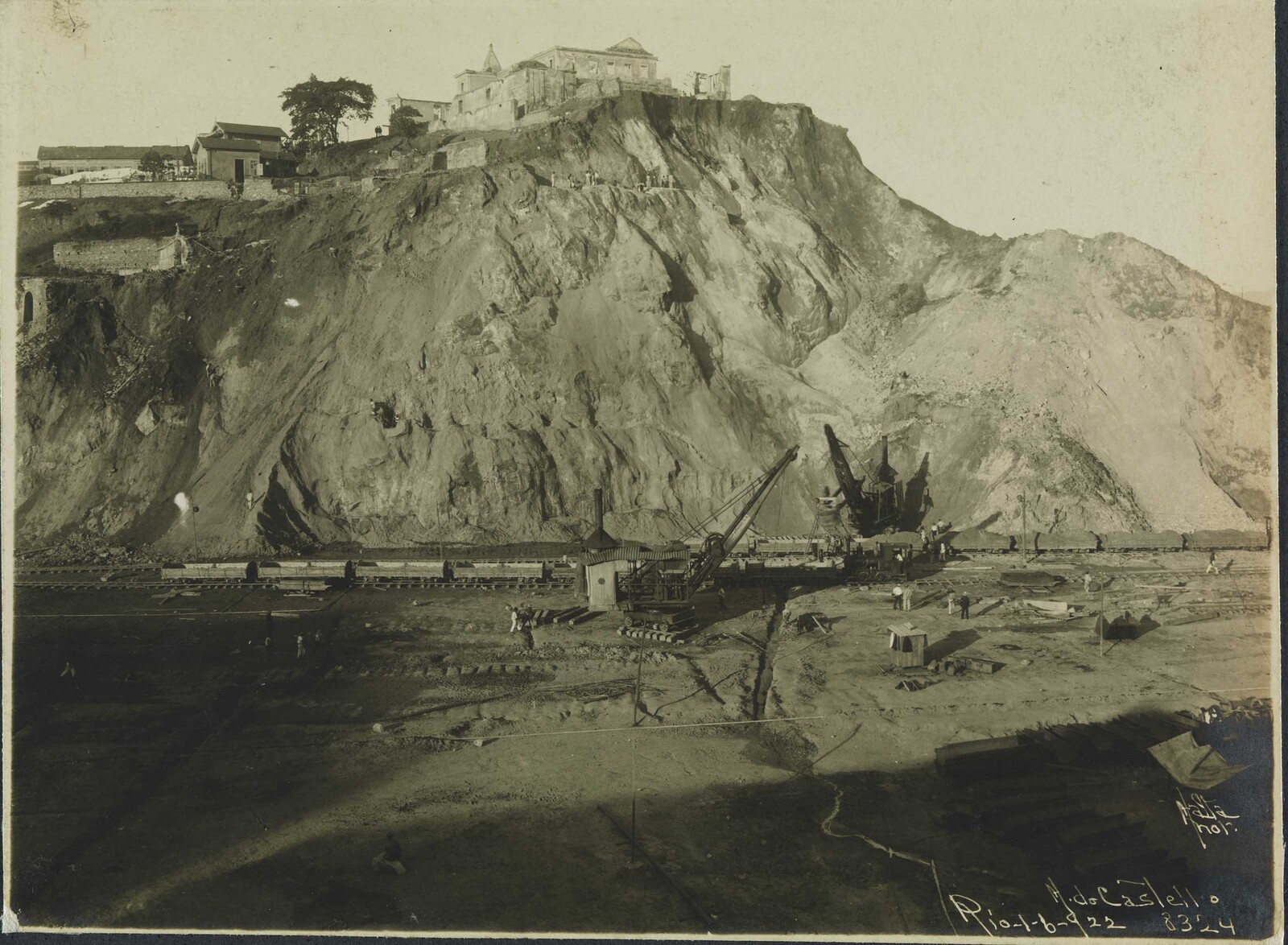

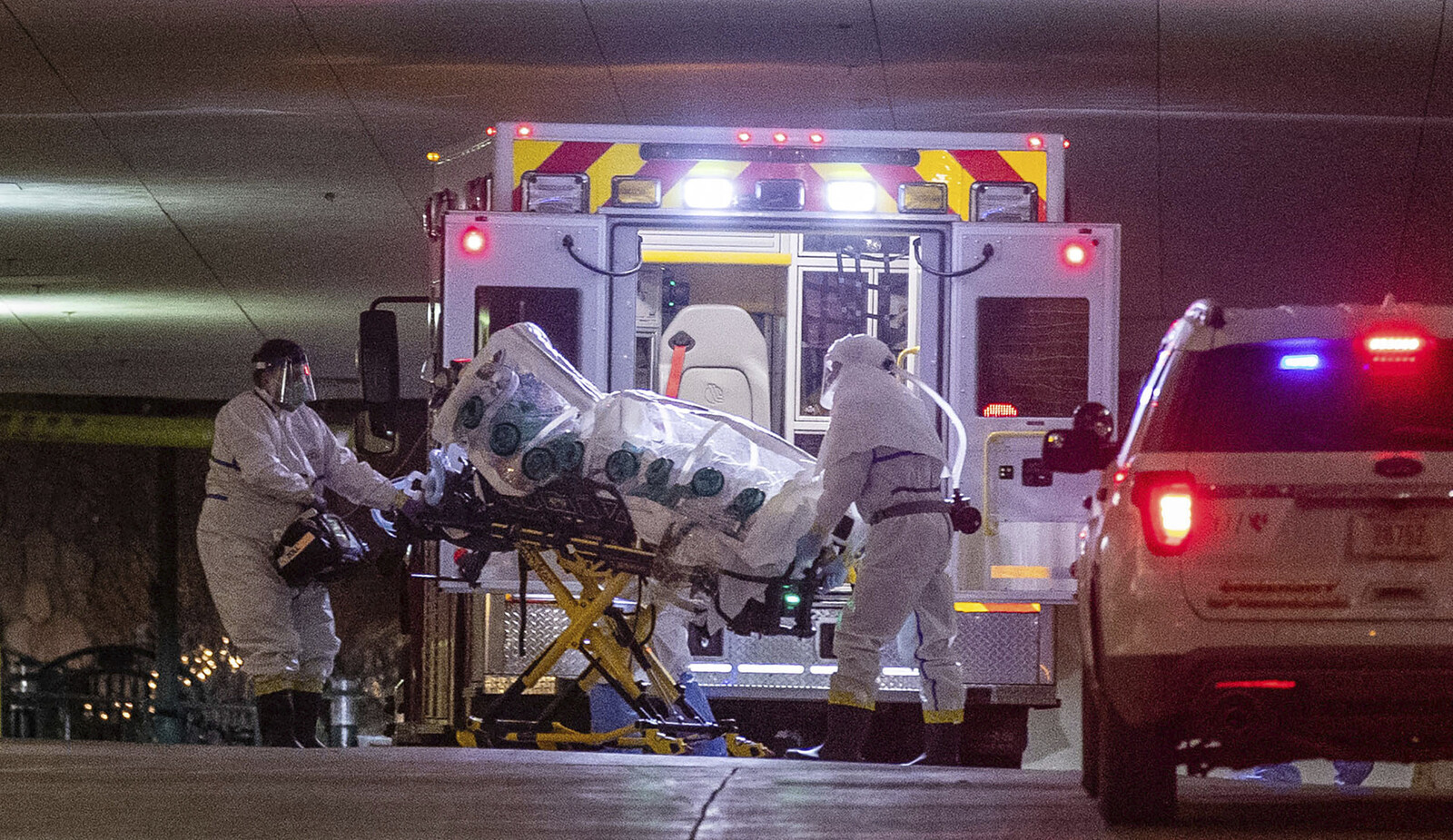

On November 10, 2020 at around 11:15pm, a house in Río Piedras, Puerto Rico went up in flames.4 A team of firefighters rushed to the site, but when they arrived, the majority of the house was gone. The fire had spread quickly across the already-damaged structure, leaving nothing but a charred foundation, limp sheets of corrugated aluminum, and a short flight of concrete stairs, now leading to a platform of smoking debris. The cause of the fire is still unknown.

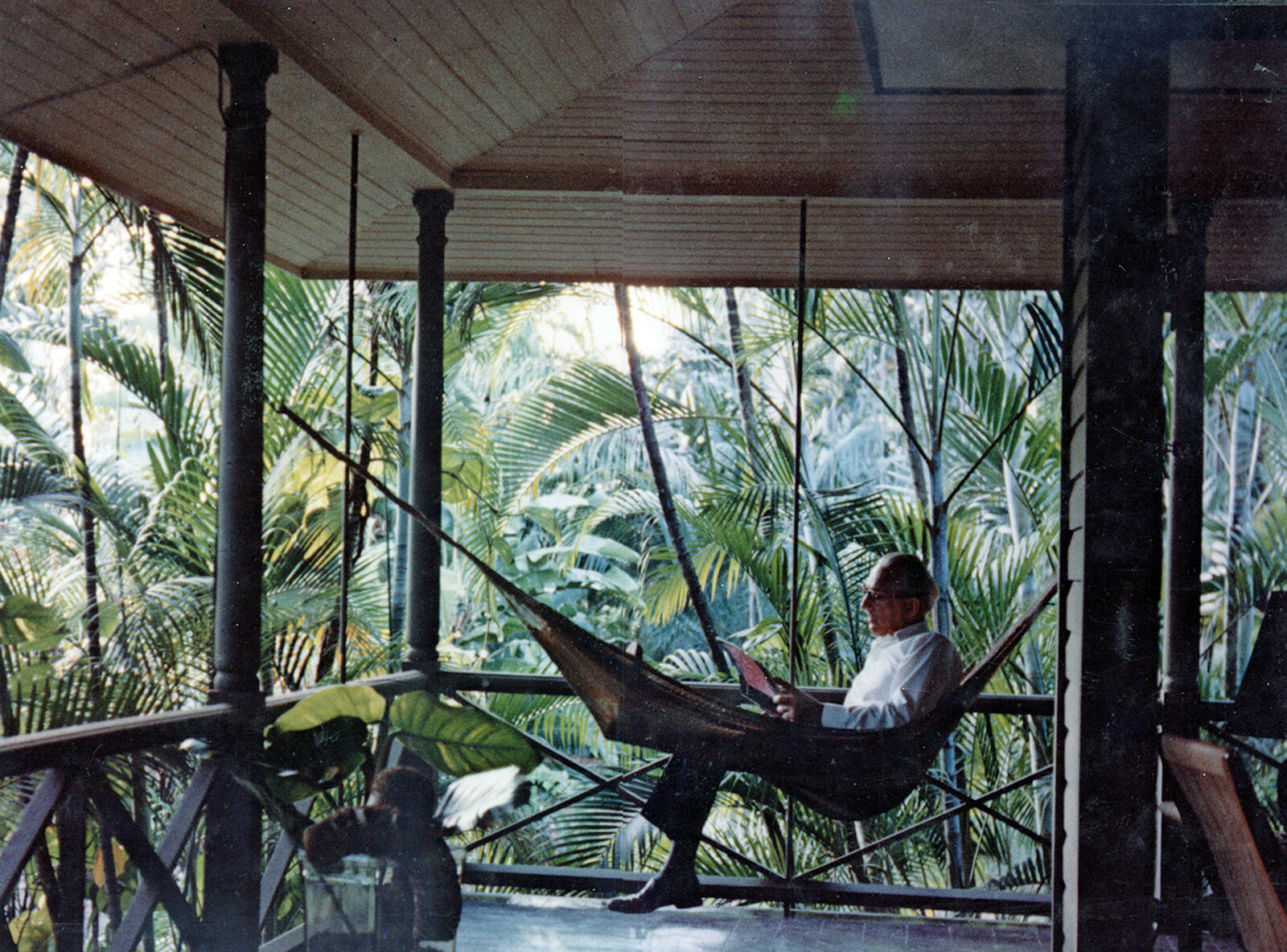

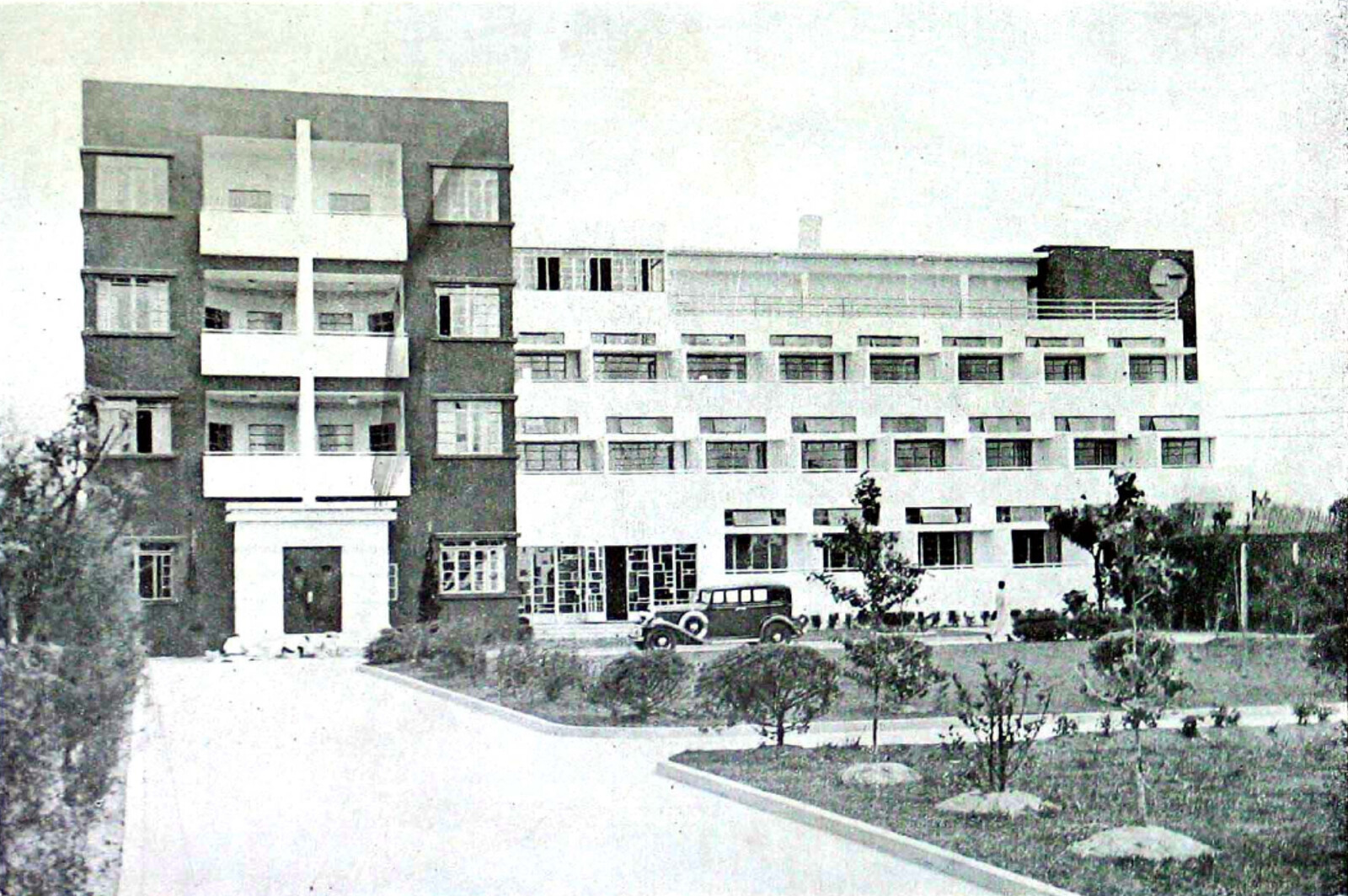

The house was known as Casa Klumb, the once-residence and architectural manifesto of Henry Klumb, a German-born architect who worked with Frank Lloyd Wright in the US from 1929 to 1933 and was invited in 1943 to serve as Director of Puerto Rico’s Design Committee of Public Works. Soon after moving to the island, Klumb purchased Rancho Cody, a seven-acre lot and former hacienda in Río Piedras.5 He transformed the existing nineteenth-century building on the property into what came to be regarded as a feat of tropical modernism, and an exemplar of Klumb’s approach to site-responsive architecture in Puerto Rico. Raised off of the ground, the single-floor house featured an open plan with very few permanent walls and was surrounded by a lush garden that protected the interior from rain and filtered the sunlight. At the center of the house was what Klumb called the “life core,” a compact area containing the kitchen, washroom, and bathroom, from which the rest of the house unfurled, opening onto the surrounding environment.6

When Rexford Tugwell, the US-appointed governor of Puerto Rico from 1941 to 1946, invited Klumb to spearhead the public works committee, Klumb saw the position as an ideal way to realize his idea of architectural practice: that instead of building according to a preconceived standard, architecture should be an “effort to solve problems.”7 Opposed to what he saw as the homogeneity of International Style architecture, he wanted to understand and respond to Puerto Rican values, issues, and traditions in his designs for low-cost rural houses, private homes, churches, and health clinics, as well as more institutional projects such as the University of Puerto Rico campus in Río Piedras. Klumb also designed the campuses of two major pharmaceutical companies, Eli Lilly and Parke-Davis, framed at the time as job-creating and economy-boosting presences on the island.8

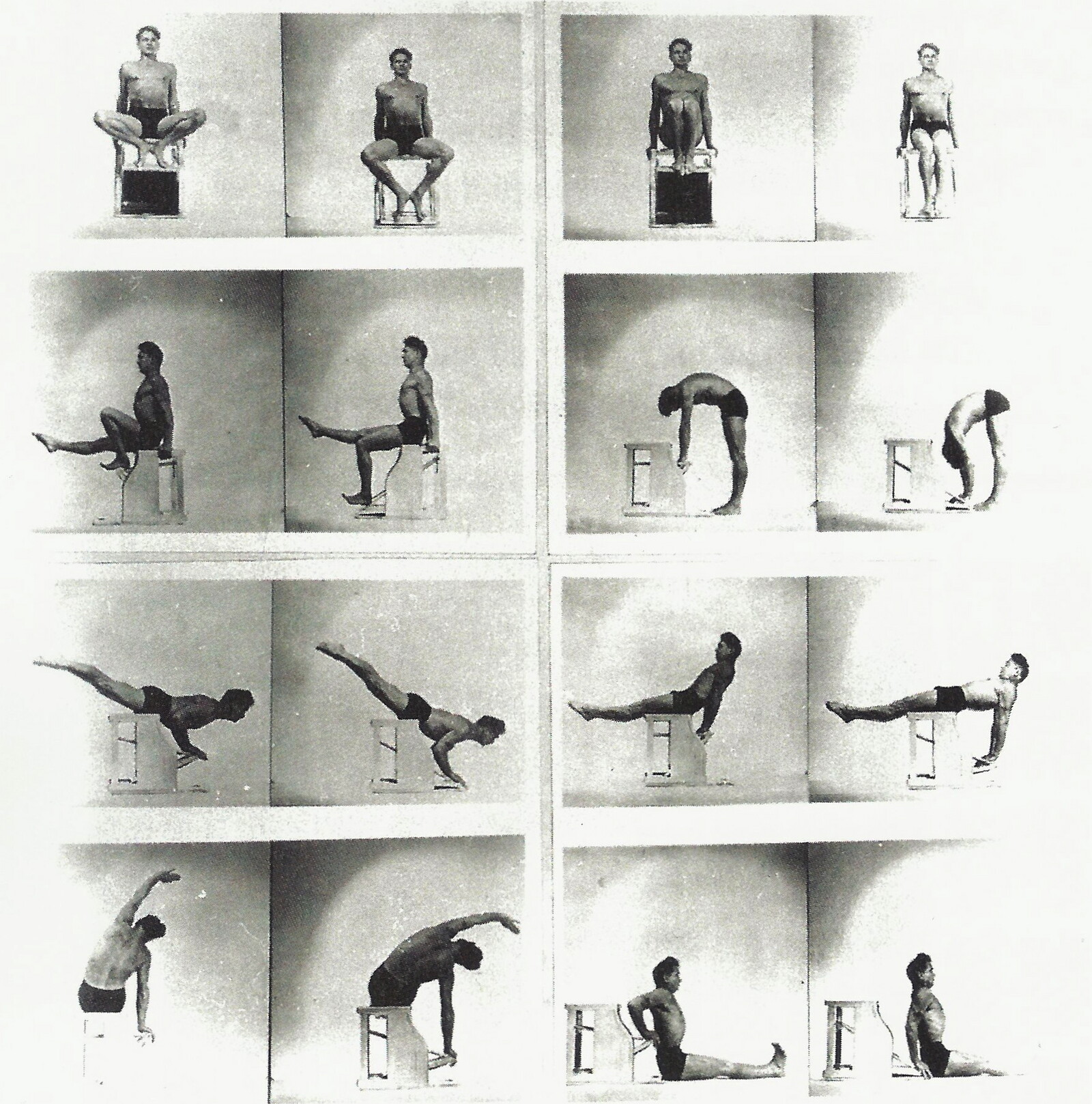

Through his work in Puerto Rico, Klumb came to imagine the modern home as a space that could “[fuse] man to his environment” and “[free] his mind,” allowing him to “coexist in free association with others [and] in conscious harmony with the varied moods of nature.”9 In this spirit, he conceived of the ideal Puerto Rican home as one that would keep out undesirable climatic conditions while allowing beneficial ones to enter. As a built manifesto of his philosophy, Casa Klumb functioned as a sort of epidermis, an idea that seems to have evolved out of Wright’s “organic architecture.” The house could adapt to shifts in temperature and weather. Its built-in dining table was made of two rectangular wings that rotated freely around a post so they could be repositioned in light or shade. Horizontal glass shutters on windows tempered the sun’s brightness. Chairs and a hammock on the large open porches were made of native woods and fibers and constructed in collaboration with local artisans.

Klumb and his wife Else lived in Casa Klumb from 1949 until their death in a car accident in 1984.10 That year, the University of Puerto Rico purchased the property and hosted architecture courses and events in the space. In 1998, however, a hurricane damaged the house’s kitchen and roof which, despite Casa Klumb’s inclusion on the National Register of Historical Places, were never fully repaired. In an effort to move toward a clear restoration plan, the house was added to the World Monuments Watch, and in 2014 an interdisciplinary task force, the Comité Casa Klumb, was formed. But the house’s metal wiring, shutters, and roof sections were looted in 2014, and more structural damage was wrought by hurricanes in 2017.11

Despite its articulated and controlled boundary between interior and exterior, Casa Klumb was immunocompromised from the start. For one, the very “nature” that Klumb focused on controlling and mediating had no single identity. It was neither purely beneficial nor fully invasive. Instead, it was at once a dangerous invention, constructed and manipulated by colonial forces, as well as a site of interconnection and history, providing knowledge and healing in the hands of the local community.

Labs and Toxic Waste

The colonial construction of nature in Puerto Rico can be traced as far back as the fifteenth century, when Spanish colonizers divided up the land in order to overwork it and the Taíno who called it home. This process picks up speed after 1952 when the archipelago (including the main island plus several smaller ones: Vieques, Culebra, Mona, Desecheo, and Caja de Muertos) was made a “commonwealth” (formally, an “Estado Libre Asociado”) of the United States. With this new category in place, the US Government began to invest in a massive industrialization of both urban and rural communities, seeking to “modernize” the island’s infrastructure and economy. This is the arena into which Klumb arrived. While Casa Klumb attests to the architect’s interest in bridging local building traditions with modernist architectural innovations, a closer consideration of some of his institutional projects (and their wider context) reveals major contradictions lurking beneath the promises of health and modernity being made by US investors and the state more generally.

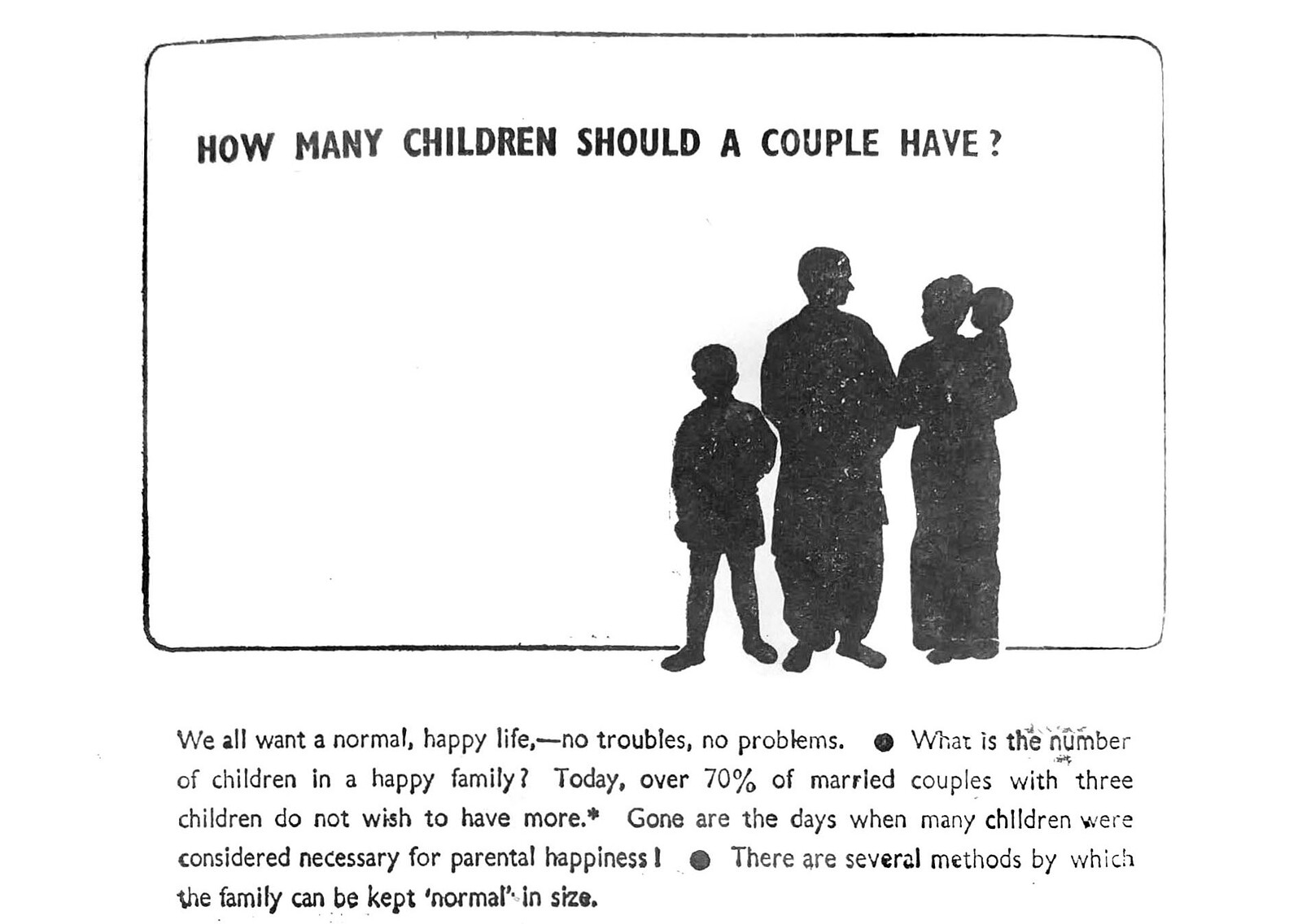

The Puerto Rican campuses of pharmaceutical companies Eli Lilly and Parke-Davis were designed by Klumb in 1968 and 1960 respectively. According to architectural historian Luz Rodríguez López, Klumb conceived of the campuses “as if they were towns,” aiming to fit the buildings into a rural setting “without competing with it.”12 He reimagined the factory as an “extension of the worker’s home instead of the reverse,” by providing airy, open spaces with plenty of natural light.13 This was beneficial from the perspective of pharmaceutical executives, who appreciated the fact that their campuses gave passersby “a pleasant feeling about us” and that the transparent architectural structures also allowed for easy surveillance of factory workers.14 Further contradictions arise when we remember that some of the drugs being manufactured in these factories, specifically birth control, were tested on Puerto Rican women in the 1950s and 1960s, often without their knowledge or consent.15 Puerto Rican laborers were thus being encouraged to be productive in a workplace that had unconsensually experimented with the reproductive freedom of Puerto Rican women in order to provide it as a choice to more privileged women elsewhere.

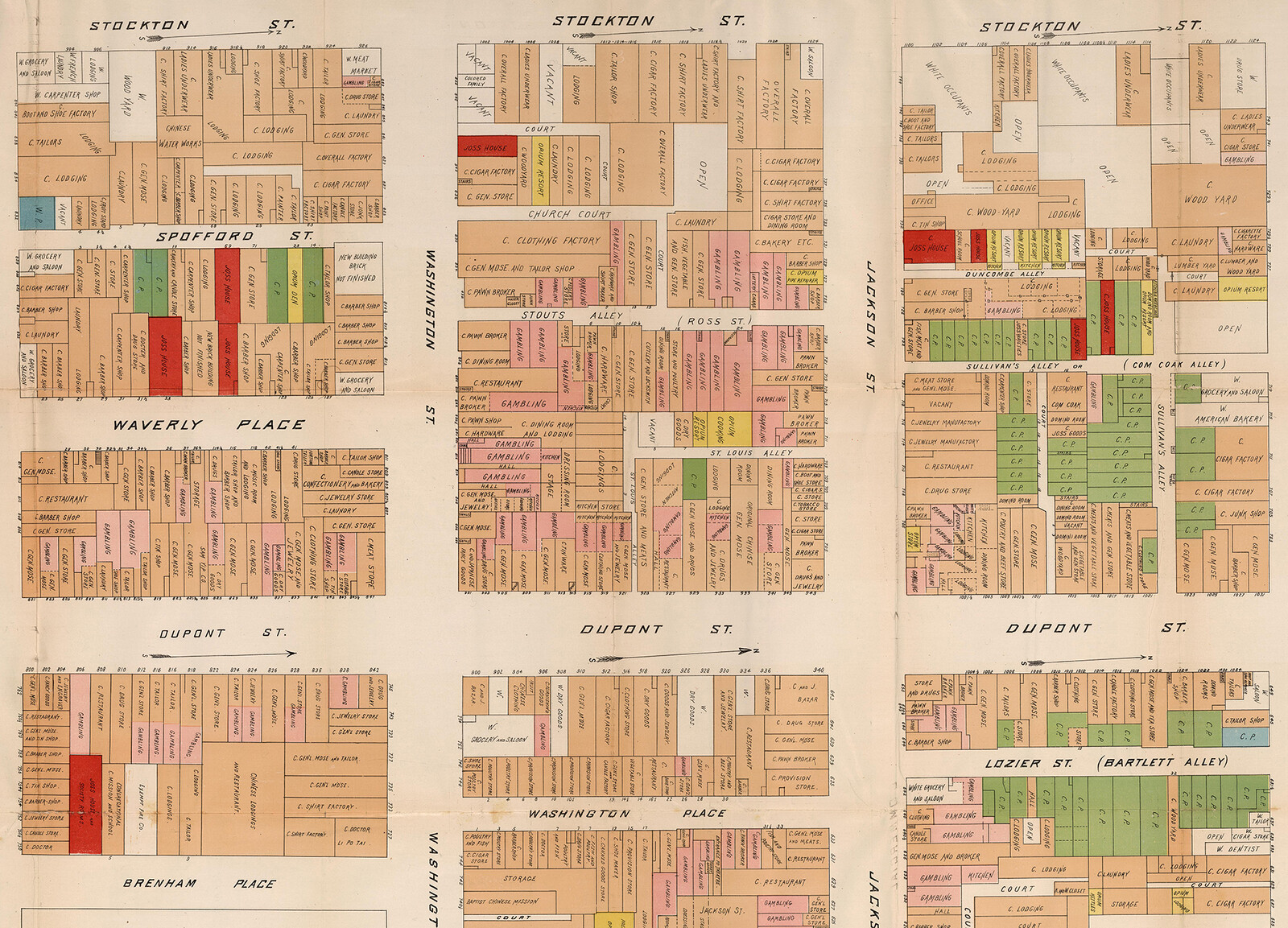

Pharmaceuticals and scientific research in Puerto Rico also had direct ecological effects. As Hilda Lloréns and Carlos G. García-Quijano have summarized, the archipelago’s mid-twentieth century modernization project—called Operation Bootstrap—involved building contaminating industrial projects in “hinterland” regions away from San Juan. This has meant that many Afro-descendant communities who live from fishing, mutual aid networks, and subsistence farming face high rates of air, water, and land pollution from oil refineries, energy generating plants, pharmaceutical manufacturers, and testing areas for GMO seeds and chemicals. In addition to being a tourist’s idyll, “nature” in Puerto Rico is the site of extractive agriculture, slavery, and in some areas, a “waste-periphery” that gravely affects the health of people whose ancestors were forced to work the fields that are now being polluted.16

Operation Bootstrap also involved building experiment stations for the US Department of Agriculture and Forest Service, as well as the establishment of the Puerto Rican Nuclear Center in 1957. Consequently, El Yunque, the largest rainforest in Puerto Rico, was designated as an experimental forest rather than a nature reserve, allowing American scientists to use the biodiverse environment as a testing site—a natural laboratory.17 One of these scientists was Howard T. Odum, who in the 1950s developed systems ecology, a study of the flow of energy and nutrients through ecosystems. In 1963, Odum was given a section of El Yunque into which he and his team used a helicopter to drop a 10,000-curie cesium gamma source (a radioactive isotope used in nuclear reactors and weapons), where it emitted radiation for over three months and destroyed foliage within a thirty-meter radius. Odum and his team then studied the forest’s recovery, allowing them “to model the ecosystem’s resilience under stress.”18

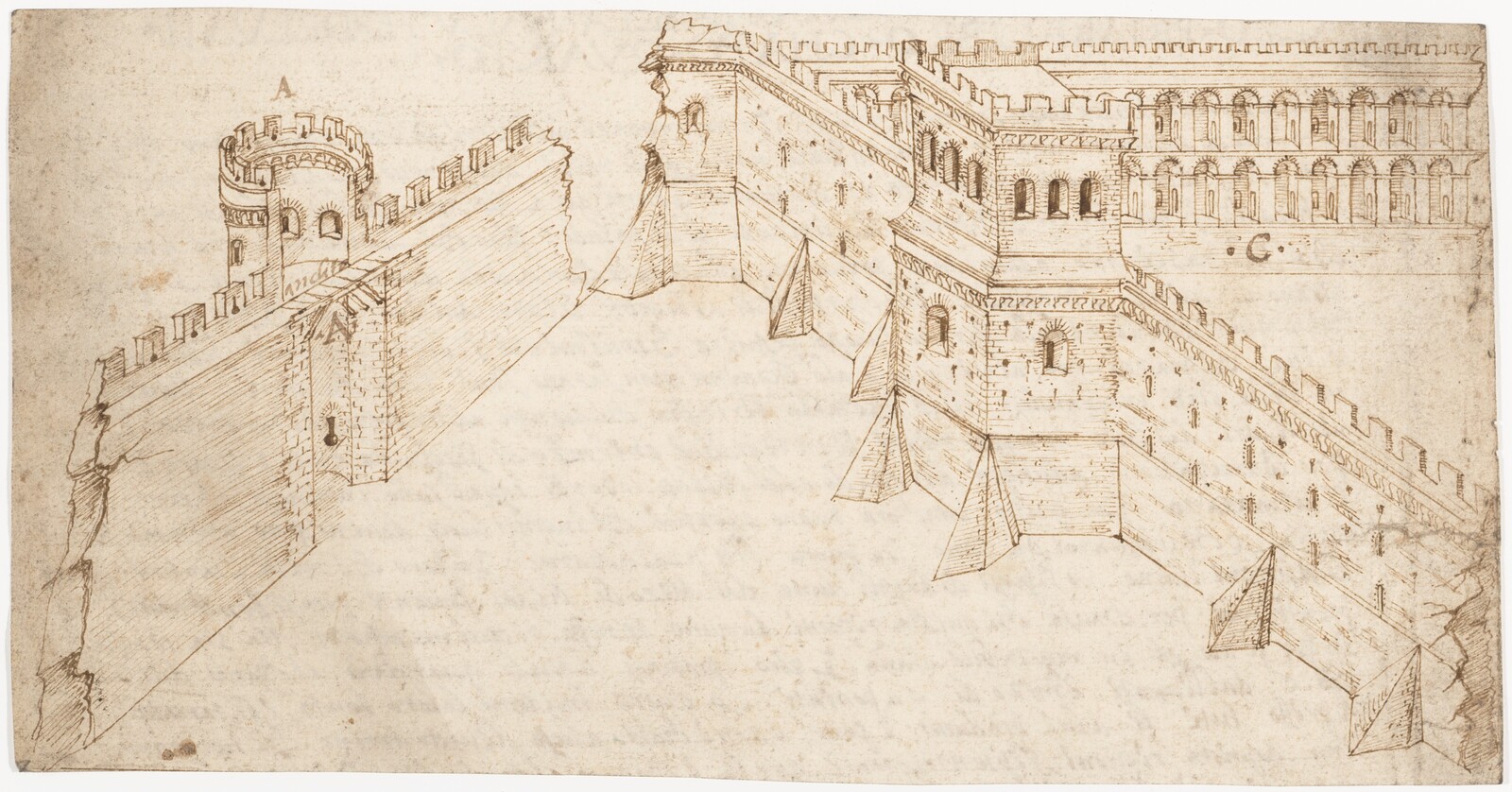

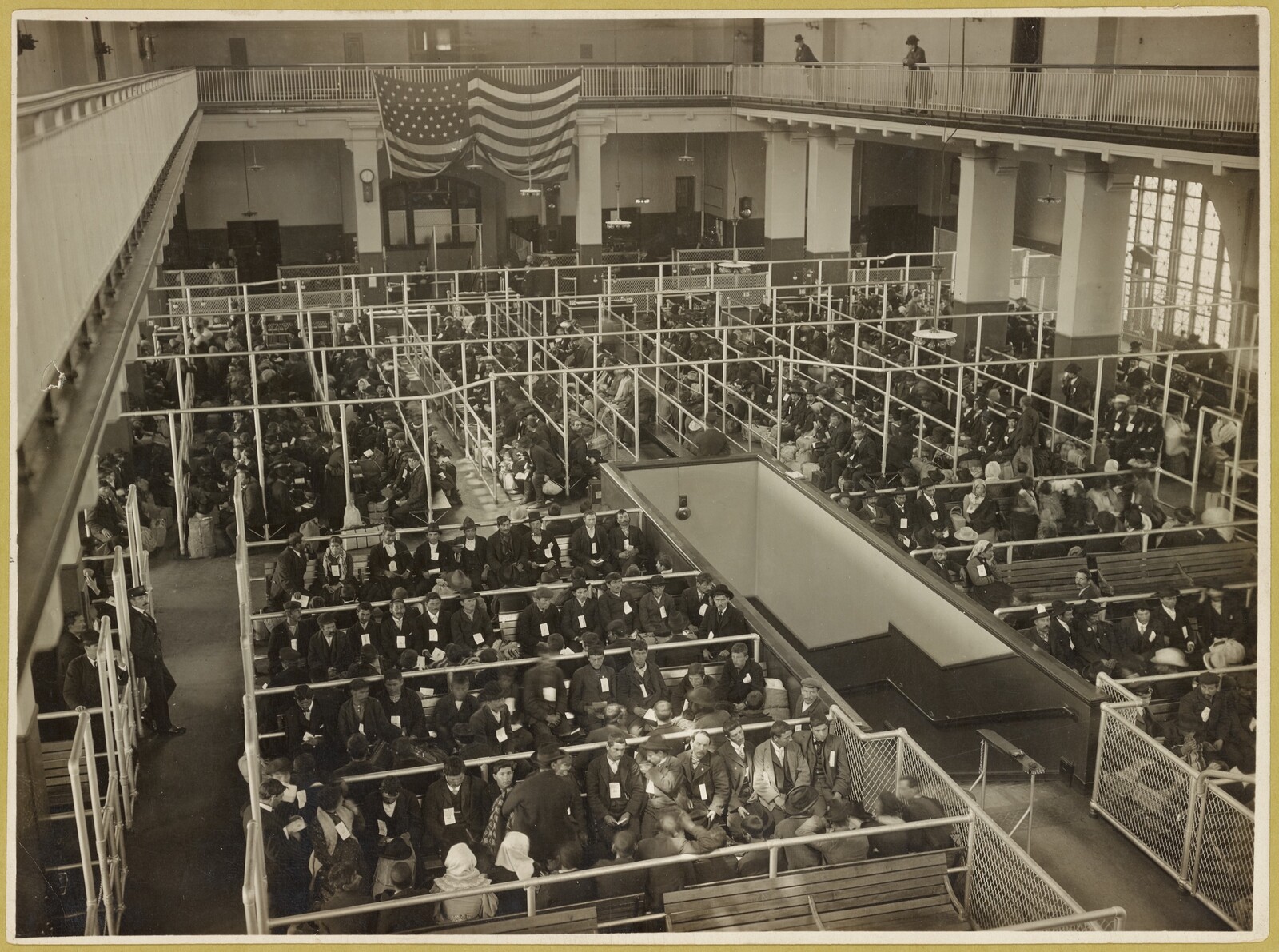

To submit a body to stress, then track its ability to withstand that stress is a common tactic in imperial attempts to seize and keep power. The colonizer reports on the resilience of the colonized. One of the first iterations of this in the Caribbean was the Jeronymite Inquiry, undertaken in 1517 on the island of Ayiti (later named Hispaniola by the Spanish, and now comprising the nations of Haiti and the Dominican Republic).19 A group of Catholic friars, charged by the Spanish Crown with administration of the island, were ordered to record the number of caciques (Taíno chiefs) and Indigenous peoples under their leadership who remained after the devastation of European-brought diseases including typhus and smallpox. The Crown wanted to know if the Taíno could serve as an adequate labor force for the extraction of gold and, eventually, the harvesting of sugar and coffee.20 The Taíno population declined rapidly and, in turn, the Spanish sent enslaved people from neighboring islands and from the African continent, continuing to track population numbers and “resilience” to both inhumane violence and new pathogens along the way.

The historian Noble David Cook has suggested that smallpox may have been brought into Taíno homes in Hispaniola from infected Spanish clothing that was given to several Taíno interpreters to wear during a trip to Spain and back.21 Clothing, the first layer of separation of body and environment, is one of the first elements of forced acculturation to European styles and norms. Seemingly banal, it nevertheless attacked both the culture and the immune systems of the Taíno. From clothing in the sixteenth century to pharmaceutical campuses and nuclear tests in the twentieth, Euro-American “gifts”—i.e., impositions of colonial ideas of health, science, and nature—weaken the boricua home again and again.

Casa Klumb, the morning after the fire. Posted on Twitter by the Colegio de Arquitectos y Arquitectos Paisajistas de Puerto Rico, Nov 11, 2020, 8:12am. Photograph by Margarita Frontera.

Gardens and Dominos

Fray Ramon Pané, a Catholic friar sent by Columbus to study Taíno culture in the early sixteenth century, noted that the Taíno called the island of Hispaniola and surrounding islands “Bohío.” This was a misunderstanding (the Taíno name for that island is Ayiti), but a revealing one. A bohío is a simple hut with dirt floors and walls and roof made of straw or palms. In the words of the Latin American Studies pioneer José Juan Arrom, bohío is also “a synecdoche for islands that are our ‘house or habitation,’ our ancestral home.”22 The reverse works as well. Actions taken against the natural environment of Borikén (the Taíno name of the archipelago) are analogous with actions taken against boricuas and their homes.

Chemical run-off and forced sterilization were certainly not Klumb’s intentions. He was operating in pursuit of that healthy, ever-evasive balance between nature and architecture. His plans for low-cost schools and homes did show real attunement to Puerto Rican materials, modes of construction, and community needs. But there is clearly still much to be learned about negotiating an always-shifting boundary between nature and architecture, about living with and in contradiction.

Between 2012 and 2014, while Casa Klumb was damaged but still intact, the artist Jorge González began to think about its past and potential futures.23 He began to work with Agustín Peréz, who had tended the gardens surrounding Casa Klumb for several decades. The gardens, designed by Klumb, were full of plants that, like the neighbors, witnessed the house in its various stages of life: from its early years as a place of gathering to its later years as an empty space, subject to nature’s intrusion. Soon, González took on the role of Casa Klumb’s gardener. He collected botanical specimens from the property, which were then added to the botanical archives of the University of Puerto Rico. He conducted interviews with several people in the neighborhood, whose knowledge of both flora and architecture opened alternative histories surrounding Casa Klumb. Discussing the gardens and the house with Sol Aida Casanova, who had lived in the neighborhood while the Klumbs resided there, González learned how the native and imported plants of Casa Klumb’s gardens functioned as a kind of provisional meeting place, a site for sharing knowledge about nature, and for adapting to its inevitable changes. Medicinal plants mingled with delicate orchids. As the house crumbled, the garden remained.

Considering the dynamic between her family—several members of which worked at Casa Klumb—and the Klumbs, Casanova remembered the first time Henry Klumb came to her uncle’s house. He had come to play dominoes.

The first time that Mr. Klumb went to play dominos it was big news. Richard [his son] came all the time, but then one day my mom said “The ‘old man’ is coming to play dominos at Yayo’s house.” The ‘old man’ was a term of endearment for Mr. Klumb. And we said, “My God!” We didn’t understand very well, because we were quite young and always playing with the idea of refusal, always saying “really?” And it was like “Black people with these rich [white] people, the millionaires of the neighborhood?” But it was this [the idea that Mr. Klumb coming to Yayo’s house would be a big deal] that I didn’t understand. I am still trying to understand it. If more people understood it, we would have fewer problems in Puerto Rico.24

Though Yayo and other neighbors worked at Casa Klumb, helping Klumb fine-tune his vision, their contributions altered the architect’s conceptions of how home and nature might be intertwined. As in dominoes, moments of equilibrium arise and provide structure. A two on one side of the domino must be abutted by another two, yet its other side remains open to an alternative connection, a four waiting for a match. Experiences of class, race, and place separated the neighbors from the Klumbs, but innovations arose in those moments when difference and sameness were held simultaneously at the fore, without the colonial compulsion toward a perfect resolve. Yayo pitched ideas for Casa Klumb’s gardens. Else Klumb became well-known in the neighborhood for her cookies. Henry and Richard came over to play dominoes.

Although the house is gone, and much of the garden’s plants have dispersed from flooding, what remains of Casa Klumb is a network of Puerto Rican artists, activists, gardeners, builders, beekeepers, and botanists who have been brought together by the house and its grounds in some way. This network is highly accustomed to shifts and subversions in the fabled balance between nature and architecture. Just as the immunocompromised body develops new means of adapting to and protecting itself from pathogens and environmental triggers, the immunocompromised home consistently transforms according to potential threats and benefits. Protesters and gardeners function like antibodies and vitamins, each specializing in a particular mode of defense and sustenance so that homeostasis can be pursued not as a given, universal ideal but as a term-to-be-reinvented.

González, for one, has continued to build off of his experience in the Casa Klumb gardens to create the Escuela de Oficios, a platform for learning from and with boricua artisans highly skilled in craft traditions and rural construction. As they continue to do for González, the neighbors who remember Casa Klumb have much to teach us about caring for the immunocompromised home in Puerto Rico. By both playing and protesting in the unstable boundary between nature and the built environment, we might give both an anticolonial future.

See Felix Contreras, “A Puerto Rico Protest Song: ‘Afilando Los Cuchillos’,” NPR.org (July 28, 2019), ➝.

Simon Romero, Frances Robles, Patricia Mazzei and Jose A. Del Real, “15 Days of Fury: How Puerto Rico’s Government Collapsed,” New York Times (July 27, 2019), ➝.

“Destruida por un incendio la Casa Klumb, patrimonio histórico de Puerto Rico,” Ey Boricua (November 11, 2020), ➝.

Heather Crichfield, Nathaniel Fúster, et al. Klumb: an architecture of social concern: una arquitectura de impronta social (San Juan, PR: La Editorial Universidad de Puerto Rico, 2007), 48.

Josean Figueroa and Edric Vivoni, Henry Klumb: Principios para una arquitectura de integracion (Puerto Rico: Colegio de Arquitectos y Arquitectos Paisajistas de Puerto Rico, 2007), 15. Klumb’s “life core” recalls what Richard Neutra called the “Block Core” facilities in his infrastructural plans for Puerto Rican slums. Richard Neutra, Architecture of Social Concern in Regions of Mild Climate (São Paulo, Brasil: Gerth Todtmann, 1948), 192.

Henry Klumb, personal papers, quoted in César A. Cruz, Puerto Rico’s Henry Klumb: A Modern Architect’s Sense of Place (New York: Routledge, 2020), 33.

Parke Davis was one of the first companies to start producing contraceptive pills once the FDA had approved them. Before FDA approval, Puerto Rican women were used in clinical trials without knowing that they were the first ones in the world to take these pills.

Cruz, Puerto Rico’s Henry Klumb, 124.

Ibid., 157.

World Monuments Fund, “Henry Klumb House,” ➝.

Luz Marie Rodríguez, “United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service, National Register of Historic Places Continuation Sheet, Section 8, Statement of Significance (continued), Casa Klumb, San Juan, PR,” (October 29, 2010), 18.

Ibid.

Ibid.

For firsthand accounts of the mass sterilization of Puerto Rican women during this period, see Ana María García’s documentary La Operación (1982).

Hilda Lloréns and Carlos G. García-Quijano, “From Extractive Agriculture to Industrial Waste Periphery: Life in a Black-Puerto Rican Ecology,” Black Perspectives, June 22, 2020, ➝.

Megan Raby, American Tropics: The Caribbean Roots of Biodiversity Science (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2017), 156.

This language has striking parallels in more recent history, as US leaders spoke often of Puerto Ricans’ resilience after Hurricanes Maria and Irma while failing to provide sufficient government aid. Ibid., 158. Also recall Donald Trump throwing paper towels into the crowd on his belated trip to the island. David Nakamura and Ashley Parker, “‘It totally belittled the moment’: Many look back in dismay at Trump’s tossing of paper towels in Puerto Rico,” The Washington Post (September 13, 2018), ➝.

Noble David Cook, “Sickness, Starvation, and Death in Early Hispaniola,” The Journal of Interdisciplinary History 32, No. 3 (Winter 2002), 351.

Ibid.

Ibid., 368.

Fray Ramon Pané, An Account of the Antiquities of the Indians: A New Edition, with an Introductory Study, Notes, and Appendices by José Juan Arrom, Trans. by Translated by Susan C. Griswold (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 1999), 8.

Jorge González developed this project as a fellow of La Práctica, which is part of the San Juan-based artistic platform Beta-Local.

Sol Aida Casanova, conversation between Jorge González, María Teresa López, Laura Cordero Agrait, and Sol Aida Casanova, San Juan, Puerto Rico, March 19, 2014. Unpublished transcript.

Sick Architecture is a collaboration between Beatriz Colomina, e-flux Architecture, CIVA Brussels, and the Princeton University Ph.D. Program in the History and Theory of Architecture, with the support of the Rapid Response David A. Gardner ’69 Magic Grant from the Humanities Council and the Program in Media and Modernity at Princeton University.