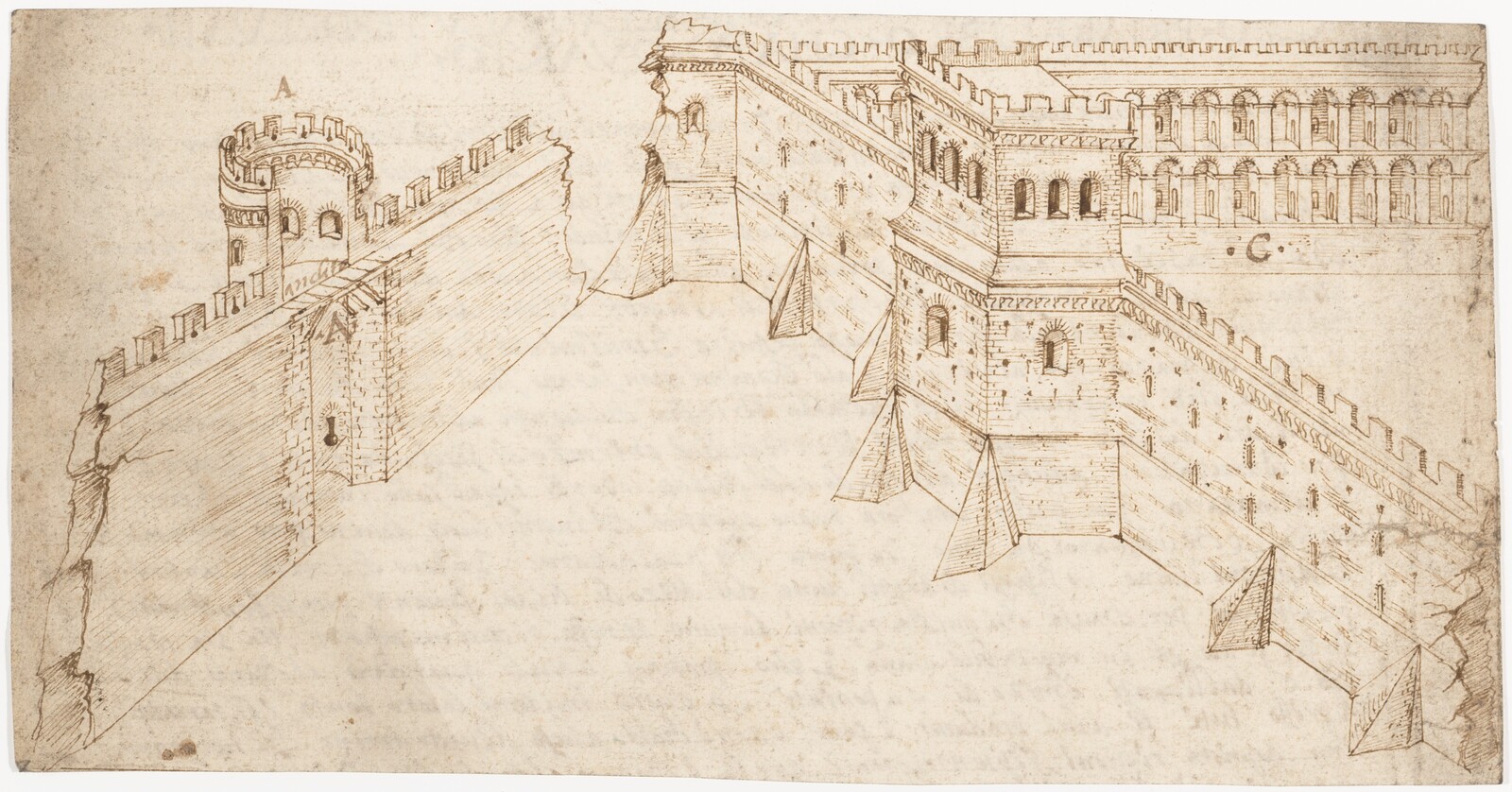

Of the many notorious origin myths of architecture, the story that directly relates to the insatiable, primordial human desire to eat remains one of the least known. As the story goes, Érysichthon, a legendary king of Thessaly, wished to design and construct an imposing palace.1 The building was supposed to feature a large feasting hall whose beam construction required substantial quantities of timber. Érysichthon decided that the nearby sacred oak forest dedicated to Demeter would deliver the necessary wood. Unsurprisingly, this was not welcomed by the goddess of earth, fertility, and grain herself. To punish the ambitious king-builder she sent the personification of hunger, who like a disease invaded the body of Érysichthon through his airways and made it so that the more Érysichthon ate, the hungrier he became. Érysichthon consumed all the palace’s and the city’s provisions before turning to his own body. From its origins, architecture was placed at the intersection of environmental crisis, disease, and hunger.

Erysichthon and Demeter, Johannes van Doetecum I and Lucas van Doetecum, after Gerard van Groeningen, published by Gerard de Jode, 1572, engraving, 205x293mm. © The Trustees of the British Museum.

The fear of hunger haunted Europe for centuries, well beyond the continent’s ancient mythologies. In early modern Europe, accounts of anthropophagy accompanying famine were seen as late as the seventeenth century. During the civil wars under the reign of Louis XIV, for instance, reports from Picardy claimed that “men eat earth and bark ‘and what we would not dare to say if we had not seen it, and which is horrifying, they eat their own arms and hands and die in despair.’”2 Similarly, in Burgundy, “the carrion of dead animals was sought after… Finally, it came to human flesh.”3 When famine occurs, however, it is never just the human stomach that is impacted: “Day by day, the houses were emptied of household goods … and the hearth became ever darker until it went out completely, the cold penetrating piercingly into the empty and desolate interiors.”4 But even in “normal” times of less acute food shortages, the masses’ at that time were largely fed with plant protein and carbohydrates, and were almost entirely deprived of animal protein, vitamins, and fat. This nutritional regime, a structural feature not only of daily life in the countryside, but also of early modern cities, made the majority vulnerable to cold and permanently left the door open to infectious diseases.

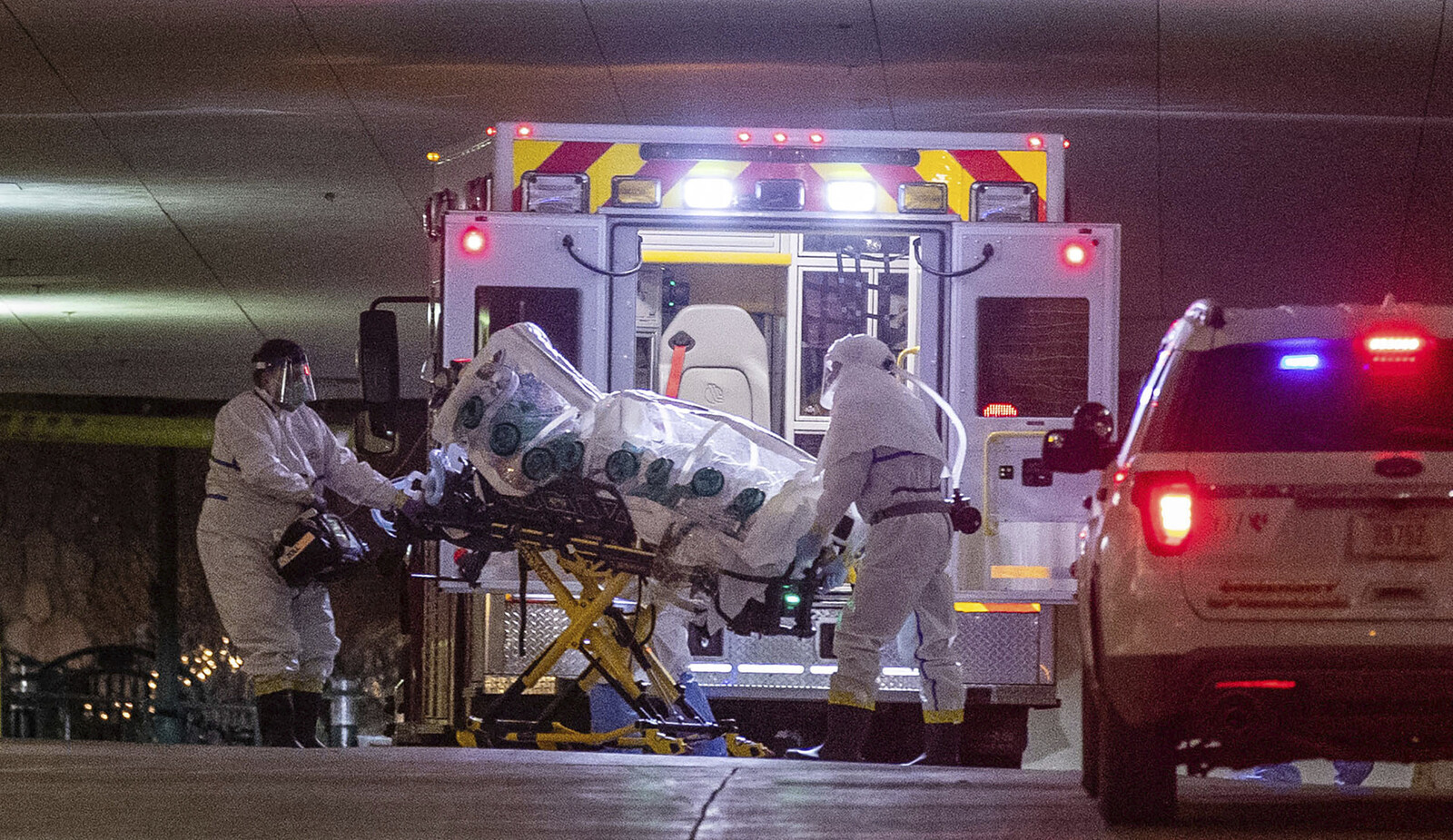

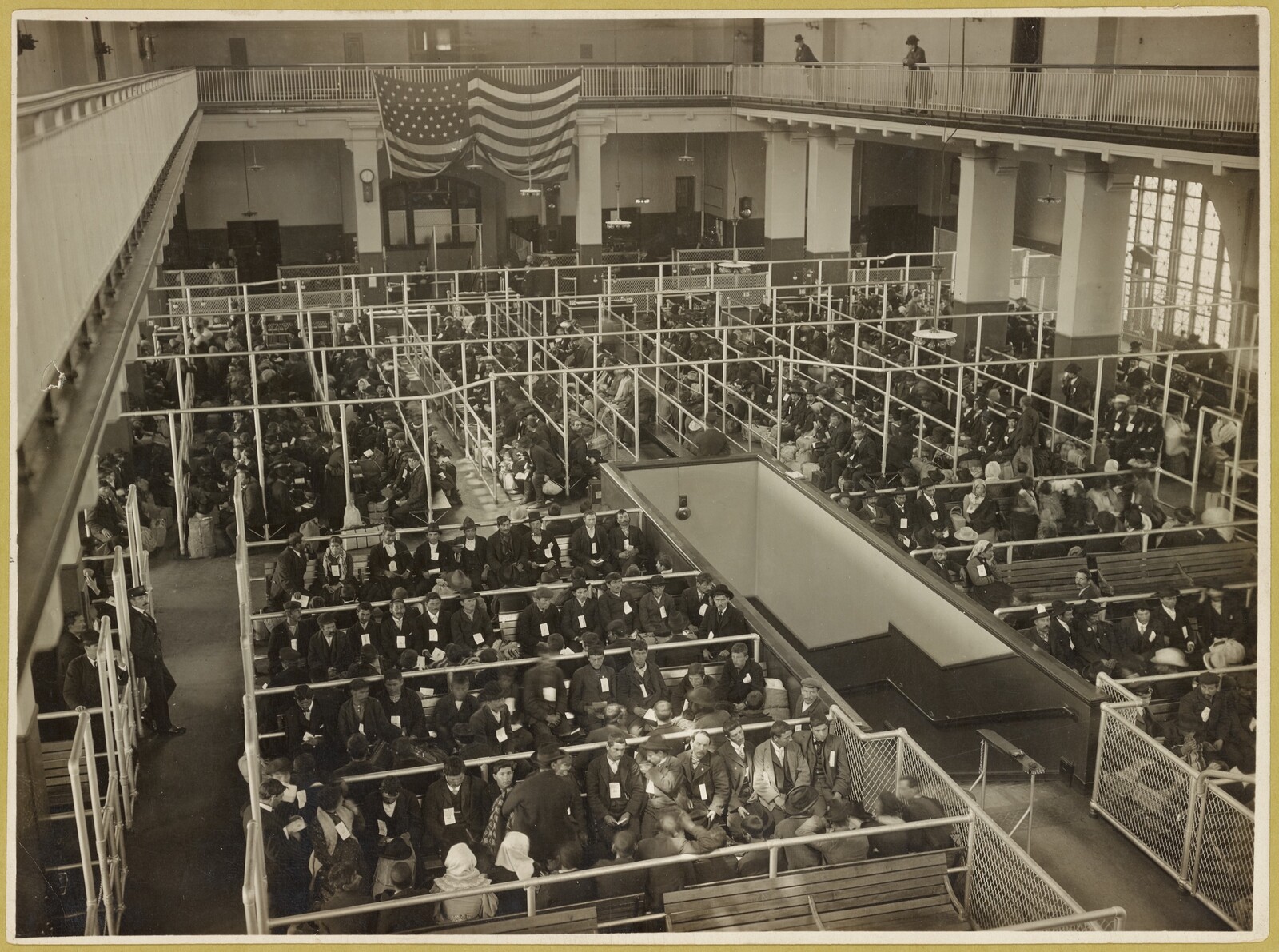

The boundary between famine and epidemics in early modern France was blurry. They were both practically endemic and killed independently, but hunger had an additional role: as a catalyst, it accelerated the work of disease, which developed more brutally on weakened organisms. It is no wonder, then, that when pandemics did occur, architecture was used to keep famine at bay, and from one crisis compounding into another. For example, according to evidence found in the military archives of Paris, once the plague appeared, concrete architectural apparatuses such as “small wooden canals” were carefully instrumentalized to deliver individual rations of food and wine to the quarantining population.5 Over the course of the eighteenth century, however, architecture became positioned in a new role, one that went beyond the practical aspect of ensuring survival in an unbearable world and towards reconstructing the space of hunger relief into an artificial paradise.

The Mise-en-Scène of Hunger

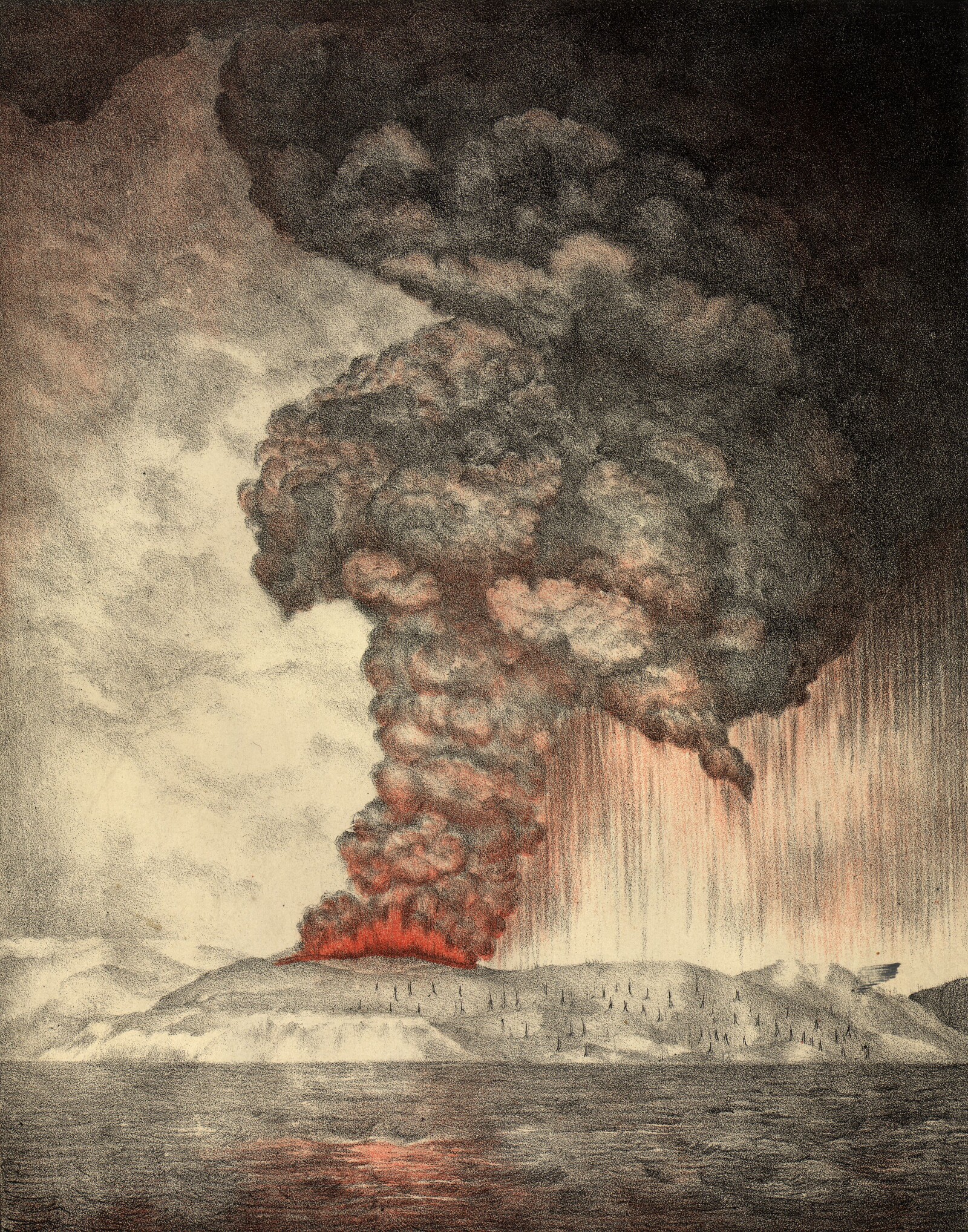

The first cause of the 1709 famine was an environmental one; the worst winter of Europe’s “Little Ice Age.” This naturally led to a terrible harvest, and whose first victims were those who died from low temperatures. During the month of January alone, Princess Palatine claimed that 24,000 Parisians died, concluding that “the plague is not worse.” In spring, grain became increasingly scarce, and by summer, prices even of the old, bad, or imported types rose sharply.6 Contaminated and spoiled breads were made with ingredients of unusual provenance, such as strange herbs, roots, ferns, nutshells and clay.7 But resorting to surrogates for flour came at a cost. Unconventional types of bread were known to alter mental states and cause delirious visions just like hunger itself, which “like mescaline produces hallucinations and the tremors of dementia.”8

By September, the famine laid the groundwork for dysentery, typhoid fever, and scurvy to spread throughout the city. “It was,” as Marcel Lachiver put it, “difficult to tell the difference between an empty stomach and a sick body.”9 In total, in less than two years, France lost 800,000 inhabitants, or about 3.5% of its population. But reducing the description of the consequences to a mere number of victims gives only partial picture. A huge stratum of the population that struggled for survival now “lived in a world … altered in the relations of time and space: a universe of completely unreal extrasensory perceptions.”10

As much as the famine might have derived from natural causes, the image of hunger and its relief was constructed. An anonymous etching of the 1709 famine held at the National Library of France depicts an operation where bread is being distributed by the King Louis XIV to a desperate crowd in front of the Tuileries Palace. Jean Delumeau described a similar event as follows: “thousands of poor people, along the hedges, with blackened and bruised faces, subdued like skeletons, most of them leaning on sticks and dragging themselves along as best they could to ask for a piece of bread.”11 In the lower left corner of the etching, a seemingly incalculable mass of hungry—and intoxicated—Parisians is quantified thanks to the gridded pattern of the palace’s courtyard and its outer fence. A glimpse into an undisturbed world of plenty is offered to the crowd through the windows of a temporary bakery and its supply chain facilities which are constructed based on the palace’s Clock Pavilion (Pavilion de l’Horloge) axis of symmetry. To relieve Louis’s delirious subjects from the famine, the operation of ensuring urban food security came to project its own “relations of time and space.”12 The hungry Parisians needed non-narcotic bread, but they were also fed with architecture.

Franz Kafka’s Ein Hungerkünstler (A Hunger Artist), a novel published shortly before his death from tuberculosis, also constructs the tension between starvation and abundance as a spectacle. Kafka describes a barred cage containing the body of the artist who deprives himself from nourishment in the center of a heavily decorated hall. The cage, an architecture of hedonistic voyeurism, allows the examination of every sign of malnutrition, and attracts hundreds of excited spectators. The most determining feature of the story, however, is again the clock, which counts down the forty-day duration of the quarantine-like performance. Kafka’s clock validated and made the accumulated time spent under the regime of starvation visible, gradually building suspense. And in the last day, in a perverse recognition of the artist’s extreme malnutrition, the room was turned into a huge feasting hall. In Kafka, as in the Tuileries, the satiation of hunger can occur by simply crossing a spatial or temporal boundary. The threshold between life and death becomes uncomplicated, medicalized, and modern; describable in mere calorific terms.13

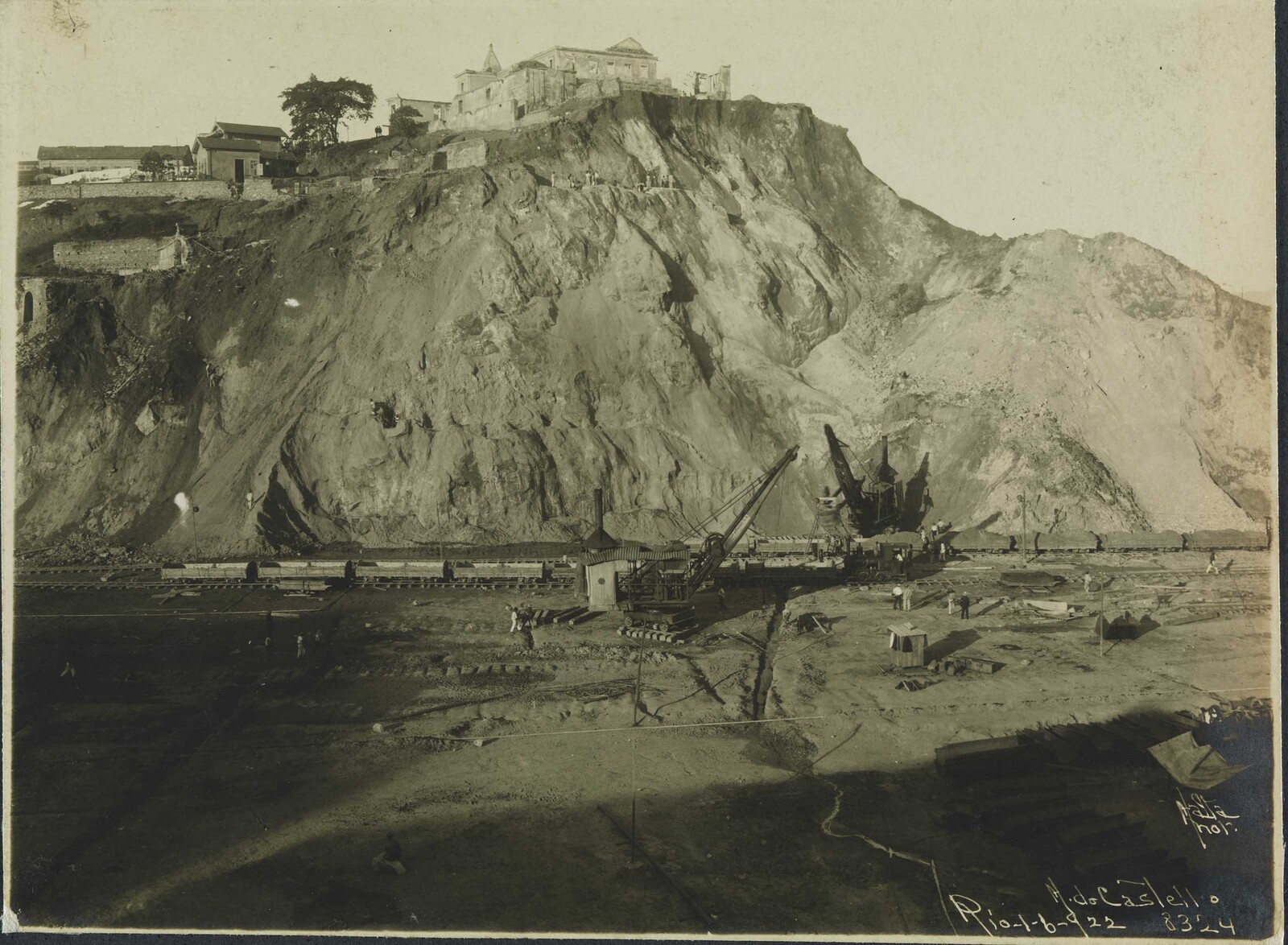

The Ground of Paris

The Tuileries etching is not a depiction of a historical event but rather a utopian, architectural project.14 Indeed, these large, white, clean gridded surfaces where Parisian bodies are controlled and fed was certainly not the ground of Paris of the early eighteenth century. Seen as an early application of an emerging ideal of hygiene, the etching might be understood better as an illustration of the proto-science fiction novel by Louis-Sébastien Mercier, The Year 2440: A Dream If Ever There Was One (1771). Mercier’s novel is organized around an imaginary walk through Paris in the twenty-fifth century. The city is an idealized, hygienic city that provides two fundamentals for its people’s health: medical treatment and proper nourishment. In case of famine, large public granaries open to provide the necessary food to citizens, while sick patients are properly treated in twenty small peripheral clinics (but which are hardly needed, since the citizens follow the hygiene protocols rigorously).15

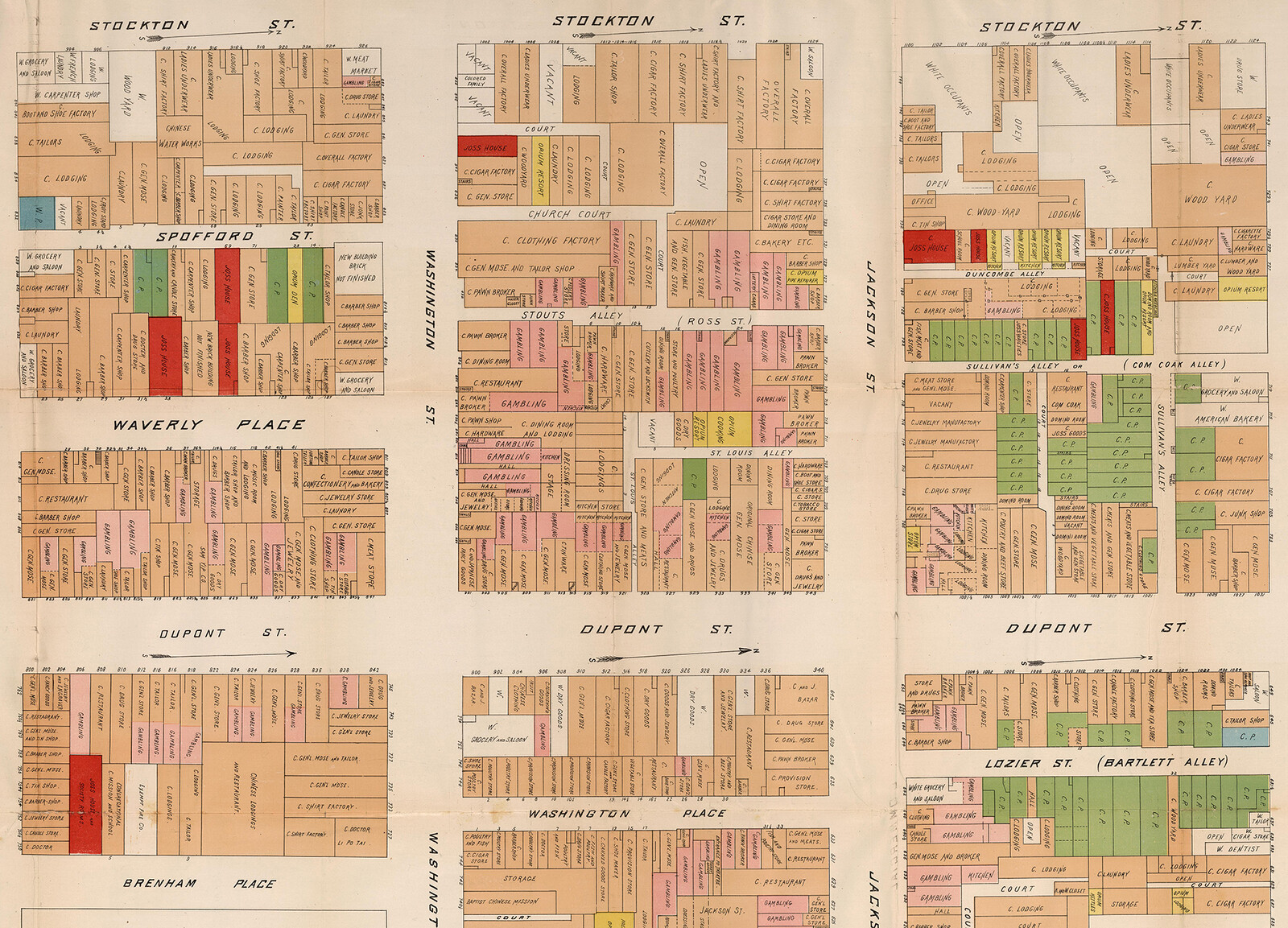

The reality of Paris in the early eighteenth century was far from Mercier’s vision. Its air was seen as stagnated and immovable, which was believed to derive from specific architectural forms. Houses on top of the city’s bridges, for instance, were believed to act as screens blocking the air from circulating freely, while other structures, like the hospital of Hôtel-Dieu, were thought to perpetually emanate miasmatic air.16 But the eighteenth century was not just the period that saw the emergence of hygienist literature that obsessively focused on doctrines of ventilation and free circulation of air within the city. It also gave rise to the theory that the urban ground itself can be as a source of “toxic” vapors, which were thought to be responsible for multiple diseases and even death.17 For example, in 1786, Pierre Bertholon published a book whose title was On The Insalubrity of The Air in The Cities, but whose stated intention was to “cast light on the tenebrous art of paving.”

Examining the city’s surfaces as sources of contagion offers a renewed understanding of how certain architectural forms emerged and worked within the larger framework of the medicalization of the urban space in eighteenth century Paris. The ground of Les Halles, for instance, the central market where both healthy and sick bodies were fed, was described by Fernand Braudel as “pestilential mud,” while others preferred words such as “disgusting” or “infectious.”18 Francoise Boudon wrote about “a thick mud which was mixed with rubbish and urine.” It was a place where “the dirt appeared in its real terms: monstrous, invasive, always present.”19 In Les Halles, the excrement of animals that pulled carriages would be added to by the chamber pots of nearby inhabitants, who did not hesitate to evacuate them directly onto ground. This is the ground upon which bags of grain for sale stood. The worst days were the ones when “toxic” vapors from the nearby cemetery were mixed with the smell of rotten fish of the nearby fish market.20 Both the ground and the bread distributed to the working classes in eighteenth century Paris was not white, but black.

Les Halles de Paris on June 18, 1927, photograph. 13x18 cm., Agence Rol, source: gallica.bnf.fr / Bibliothèque nationale de France, département Estampes et photographie.

The Granary, the Hospital, and the City

Grain in eighteenth century Paris was seen to be like air, in that it should never be stagnant. One important principle that governed trade at Les Halles at the beginning of the eighteenth century was that storage was not allowed. The absence of a canopy in the market was, above all, an issue of public health: it ensured the continuous replacement and ample ventilation of the grain that was sold.21 It was also thought to accelerate the sales of bread while keeping the prices low.22 The open-air market was the architectural apparatus designed to secure the constant flow of calories from the countryside to the stomachs of the citizens. But without the possibility of storage, food security had very thin lines of defense. Les Halles’ primordial role in Parisian homeostasis became evident with only the slightest disruption in the grain market or supply chain.

Les Halles became the laboratory for the modern healthy, hygienic, and safe city. Here, within fifty years of the 1709 famine, the architecture that dealt with the flow, consumption, and storage of calories had undergone dramatic evolution. In 1763, for instance, the Halle au Blé, a new public granary at the heart of Les Halles designed by Le Camus de Mezieres, was devised to separate the food from its ground; sterilizing Parisians’ nourishment by insulating it from any “toxic” exhalations. However, this design did not just attempt to remove the fear of disease; it also aspired to control the fear of hunger. By lifting the grain approximately nine meters overhead, above the market floor, the public was now able to hedonistically inspect whether enough provisions were available and if famines anywhere to be seen. This form of transparency was welcomed by police officers, who manipulated the stocks of grain in the Halle au Blé, intoxicating Parisians’ fear of hunger whenever necessary.23 Conversely, an image of abundance was often put on display, regardless of whether it was real or not.

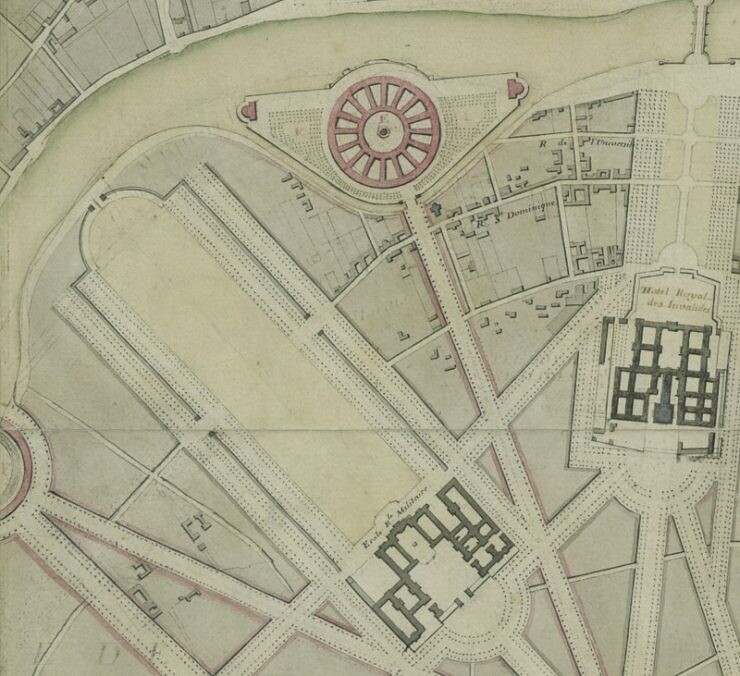

Plan général du projet des embellissements de Paris (detail), Charles de Wailly, 1785. Source: gallica.bnf.fr / Bibliothèque nationale de France, département Cartes et plans.

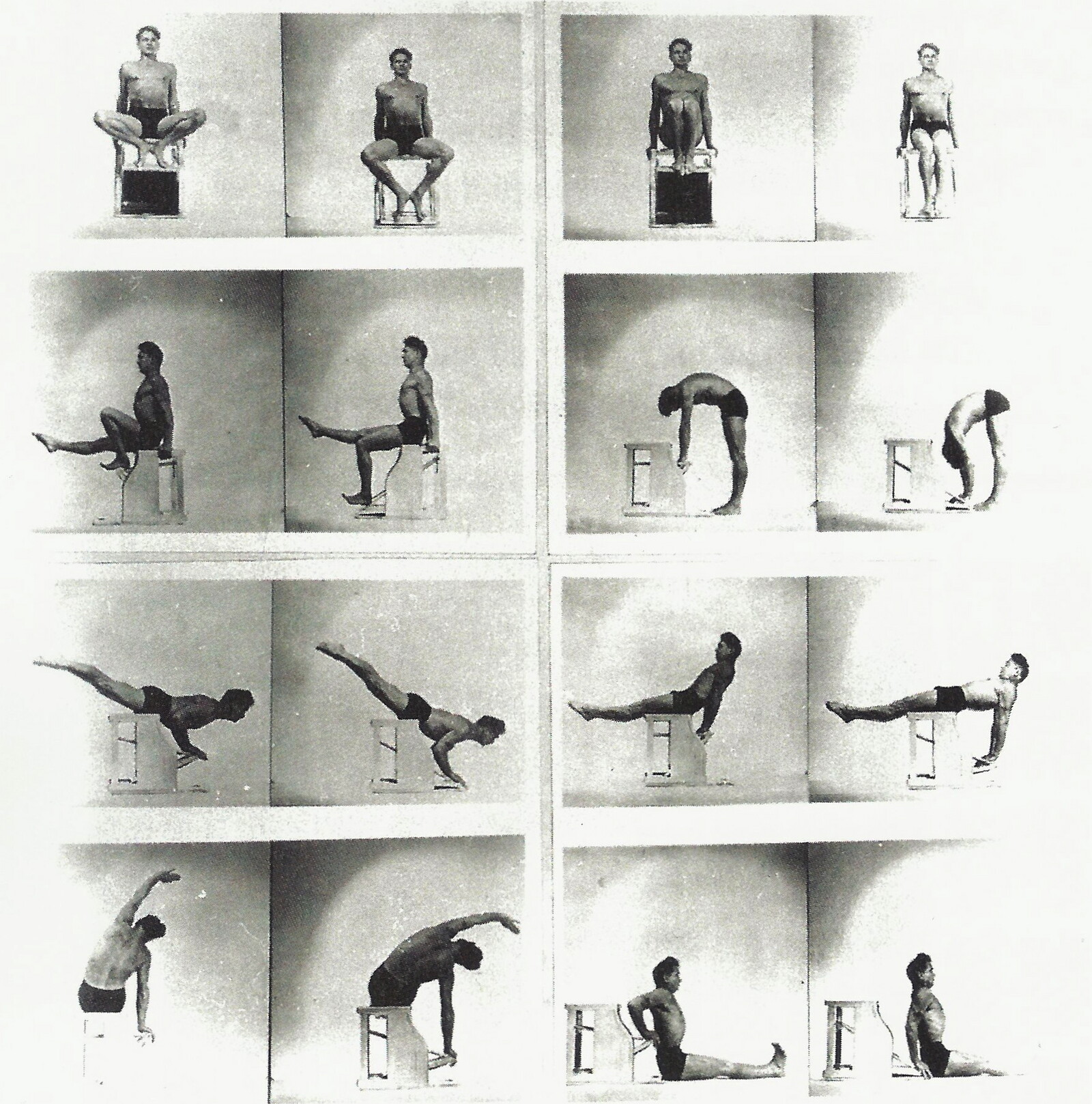

The development of the typology of the public granary ran in parallel with that of another new typology, the public hospital. In fact, as Meredith TenHoor recently pointed out, much of the “machine to heal” could also be found in the “machine to feed.”24 The functional and compositional parallels between the two typologies were expressed most succinctly by the architect Charles de Wailly in 1785, who appropriated Bernard Poyet’s project for a new Hôtel-Dieu and coupled it with a new Halle aux Blés when proposing a new configuration for the Champ de Mars area. Here, the two programs were not simply juxtaposed, but appeared as complementary; two poles that treated the sick and healthy bodies of the Parisians in two different ways. The public granary was, according to Wailly, more than a place of supplying grain and bread; it had become a place of well-being. His project even offered the possibility to use the granary’s water basin during summer months for recreational swimming and even for water sports.

In the space of a few decades, then, the distribution of bread was transformed from a space of necessity, disease, famine, and anxiety to a space of commodity, hygiene, pleasure, and spectacle; from a space of hunger to a space of abundance. Like today’s apparatus that keeps quarantining populations fed, the architecture of hunger transformed necessities into commodities by creating new artificial paradises, microcosms of ideal cities and model apparatuses through which the promise of a hygienic, abundant modernity projects itself onto those experiencing its unbearable realities.

Callimachus (Sixth Hymn to Demeter, 3rd century BC) and Ovid (Metamorphoses 8, 1st BC and 1st AD) are the primary ancient sources for this myth.

Jean Delumeau, La Peur en Occident (XIVe-XVIIe siècles): Une Cité Assiégée (Paris: Fayard, 1978), 164.

Ibid.

Piero Camporesi, Bread of Dreams: Food and Fantasy in Early Modern Europe, trans. David Gentilcore (Cambridge: Polity Press, 1989), 56. For a contemporary understanding of the ways famines intersect with architecture, see Ateya A. Khorakiwala, The Well-Fed Subject: Modern Architecture in the Quantitative State, India (1943-1984), Doctoral dissertation (Harvard University, Graduate School of Arts & Sciences, 2017).

Michel Foucault, Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison, trans. Alan Sheridan (New York: Vintage, 2012), 195.

Pierre Goubert, Louis XIV et Vingt Millions de Français (Paris: Fayard, 1991), 272.

Marcel Lachiver, Les Années de Misère: La Famine au Temps du Grand Roi, 1680-1720 (Paris: Fayard, 1991), 356.

Camporesi, Bread of Dreams, 127.

Lachiver, Les Années de Misère, 354.

Camporesi, Bread of Dreams, 127.

Delumeau, La Peur en Occident, 163.

Camporesi, Bread of Dreams, 127.

See: Agustí Nieto-Galan, Mr Giovanni “Succi Meets Dr Luigi Luciani in Florence: Hunger Artists and Experimental Physiology in the Late Nineteenth Century,” Social History of Medicine 28, 1 (February 2015): 64–81; also: Jenny Edkins, Whose Hunger?: Concepts of Famine, Practices of Aid (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2000), 15-41.

The north wing of the palace is entirely fictional, while the open square in front of the building is devoid of all the constructions that were built there at the time.

Louis-Sébastien Mercier, L’An Deux Mille Quatre Cent Quarante. Rêve s’il en fut jamais (London, 1771), Chapters 8, 14, 23.

See: Etlin Richard, “L’air dans l’urbanisme des Lumières.” Dix-huitième Siècle, Le Sain et le Malsain 9 (1977): 124. Also: Nikolaus Pevsner, A History of Building Types (Washington: Thames and Hudson,1976), 146.

See: Sabine Barles, “La Pédosphère Urbaine : Le Sol de Paris XVIIIe-XXe Siècles” (PhD diss, École Nationale des Ponts et Chaussées, 1993), 91–123.

Fernand Braudel, Capitalism and Material Life, 1400-1800, trans. Miriam Kochan (London, Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1973), 437.

Boudon Françoise, “La Salubrité du Grenier de l’Abondance à la fin du 18e siècle.” Dix-huitième Siècle, Le Sain et le Malsain, 9, (1977): 171-180.

Steven Laurence Kaplan, Les Ventres de Paris: Pouvoir et Approvisionnement Dans la France d’Ancien Régime, trans. Sabine Boulonge (Paris: Fayard, 1988), 92–93.

Mark K. Deming, La Halle au Blé de Paris: 1762-1813: “cheval de Troie” de l’abondance dans la capitale des Lumières (Bruxelles: Archives d’architecture moderne, 1984), 58.

At least, this was La Reynie’s argument when he opposed the grain merchants’ request for the construction of a roof, claiming that if the merchants did not have to fear the rain, they would be in no hurry to sell and prices would inevitably rise. See Léon Bernard, The Emerging City: Paris in the Age of Louis XIV (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1970), 253.

Deming, La Halle au Blé de Paris, 116.

About the Halle au Blé, its role in relation to hospitals, grain circulation and hygiene see: Meredith TenHoor, “Architecture and Biopolitics at Les Halles,” French Politics, Culture & Society 25, no. 2 (2007): 73–92; Meredith TenHoor, “Markets and the Food Landscape in France, 1940–72,” Dumbarton Oaks Colloquium on the History of Landscape Architecture 36 (2015): 333–351.

Sick Architecture is a collaboration between Beatriz Colomina, e-flux Architecture, CIVA Brussels, and the Princeton University Ph.D. Program in the History and Theory of Architecture, with the support of the Rapid Response David A. Gardner ’69 Magic Grant from the Humanities Council and the Program in Media and Modernity at Princeton University.

Category

Subject

This essay was supported by the Onassis Foundation, Scholarship ID: F ZQ 055-1/2020-2021.