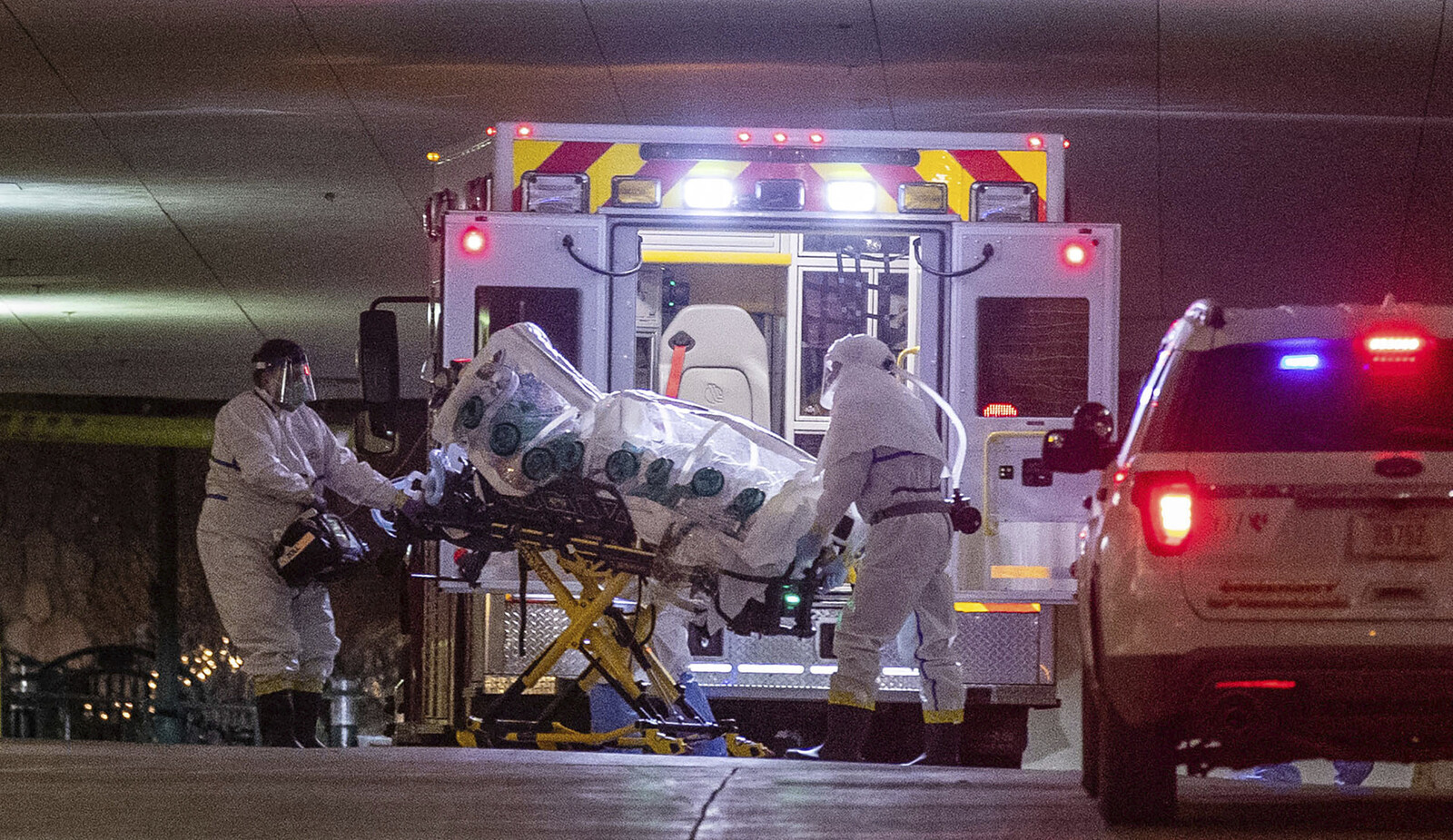

The Covid-19 pandemic has revealed that international borders pervade far beyond their physical sites in order to alienate from within. In the United States, a recent study demonstrated that people who were primed to think of Covid-19 were roughly twice as likely to choose not to live with Hispanic and Asian roommates as those who researchers did not prime to think of the disease.1 Amid the pandemic’s first intrusion into the country, House Speaker Nancy Pelosi travelled to San Francisco’s Chinatown to support its hard hit businesses on the very same day that one of the Bay Area’s largest dailies ran a headline posing the question, “Where did our quarantine facilities go?” atop an image of nearby Angel Island.2

Angel Island first served as a Miwok fishing ground before the Union Army established a fort on its western tip amidst the Civil War.3 In 1888, a smallpox outbreak in Hong Kong prompted the US Public Health Service to establish a quarantine facility for ships arriving from the Pacific on Angel Island’s Ayala Cove. The quarantine station’s forty-five structures included a fumigation shed, a hospital, employee lodgings, and quarantine facilities capable of holding 500 people at a time.4 Who quarantined on Angel Island was largely a function of race and class. First class passengers often disembarked in San Francisco after cursory checks in the privacy of their own cabins, while passengers in steerage, largely Asian laborers, spent two weeks on the island while officials bathed and inspected them.5

The 45 structures of the quarantine station hugged Ayala Cove. Ayala Cove, 1948. Source: San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library.

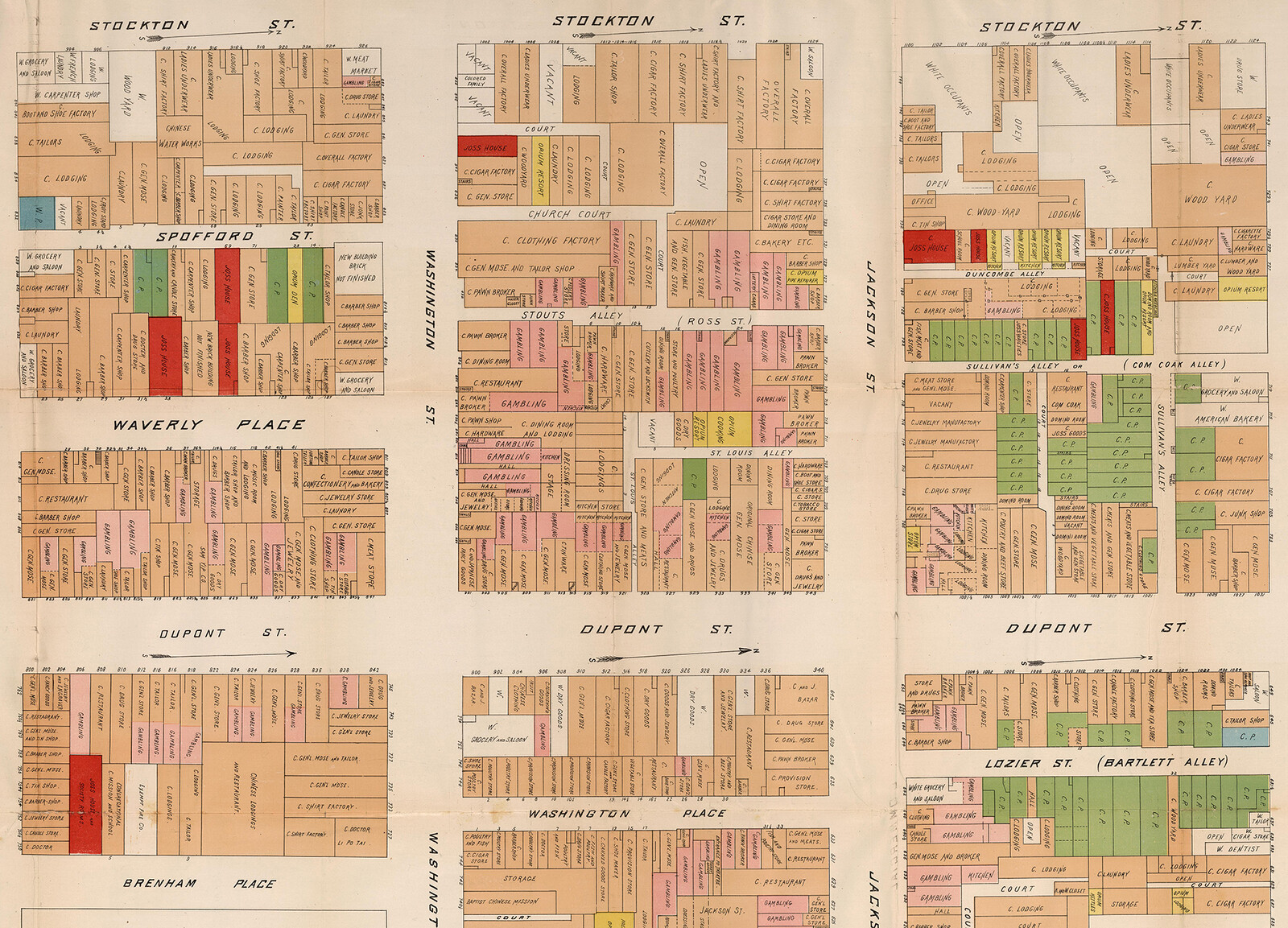

Segregated quarantine procedures reflected the anti-Chinese, medicalized political atmosphere of the time. In 1862, American surgeon Arthur B Stout conflated Chinese labor with racial impurity and national decay.6 Despite the critical role of Chinese labor in the construction of the transcontinental railroad in the 1860s, by 1882 The Daily Alta California surmised that “the State is diseased by the presence of the Chinese,” and the federal Chinese Restriction Act from the same year made working class Chinese men the first group barred from naturalization.7 Expanding this ban six years later, President Grover Cleveland described the arrival of Chinese labor as “injurious to both nations.”8 A year later, San Francisco satirical weekly The Wasp published a political cartoon depicting Uncle Sam struggling to stop a flow of Chinese men depicted as the size of rodents, invoking a plague.

With Chinese labor seen as a disease to the country, Angel Island became an ideal laboratory for testing new modes of prevention. During its operation, the Angel Island Immigration Station processed about half a million people, deported about one in five, and detained several hundred at once.9 For those it allowed to enter onto the mainland, Angel Island disciplined new arrivals into a rigid racial hierarchy in which they would be marked perpetually foreign. While a broad swath of Pacific passengers experienced the station’s brutality, it played an outsized role as a tool of Chinese exclusion. Lengthy investigations used to enforce the Chinese Exclusion Acts created prolonged detention periods that required specific architectures of containment. The ensuing complexity of the station was a point of pride within the city of San Francisco. Three years before the station opened in 1910, the San Francisco Chronicle lauded its anticipated methods of segregating and analyzing arrivals, calling it “The Finest Immigration Station in the World.”10

Well before the station was completed, the San Francisco Chronicle printed a full page of praise for the station’s architect. “San Francisco to Have the Finest Immigrant Station in the World,” San Francisco Chronicle, August 18, 1907.

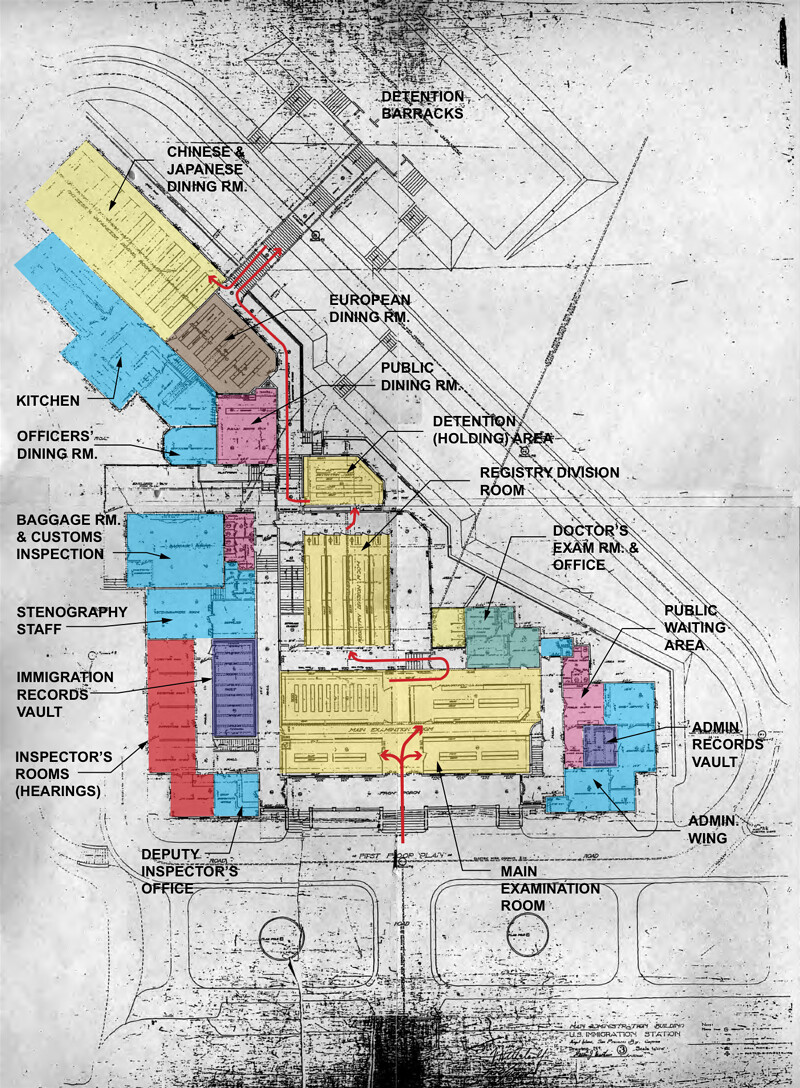

The interior divisions of the Administration building kept arrivals separate along lines of race and gender, and kept them apart for the duration of their stays. Daniel Quan, Administration Building first floor plan, 2015.

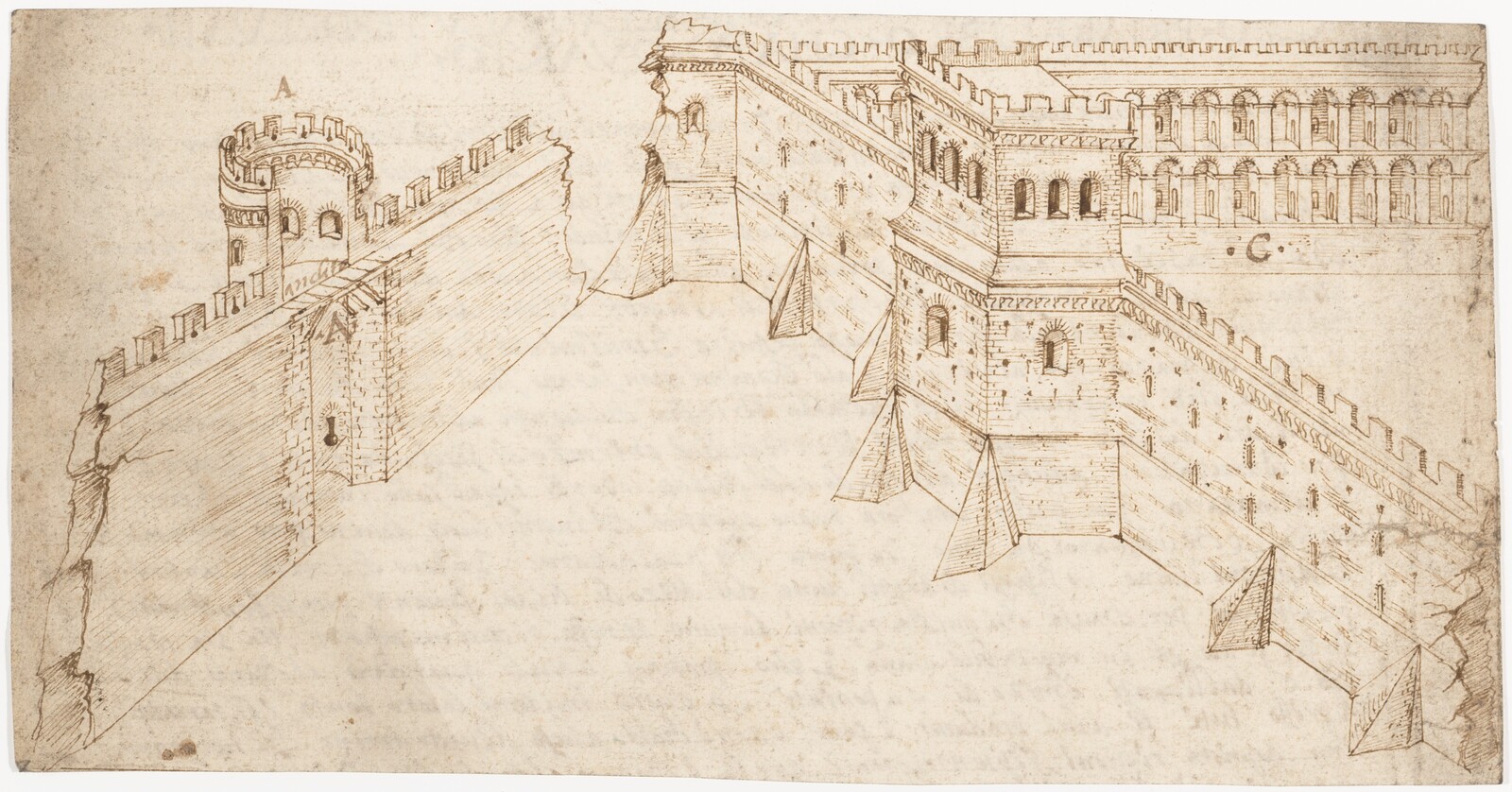

An original drawing of the immigration station complex shows the four main buildings before the construction of the staff cottages and fumigation shed. Walter J. Mathews, Angel Island Immigration Station, 1907. Source: California History Room, California State Library.

Well before the station was completed, the San Francisco Chronicle printed a full page of praise for the station’s architect. “San Francisco to Have the Finest Immigrant Station in the World,” San Francisco Chronicle, August 18, 1907.

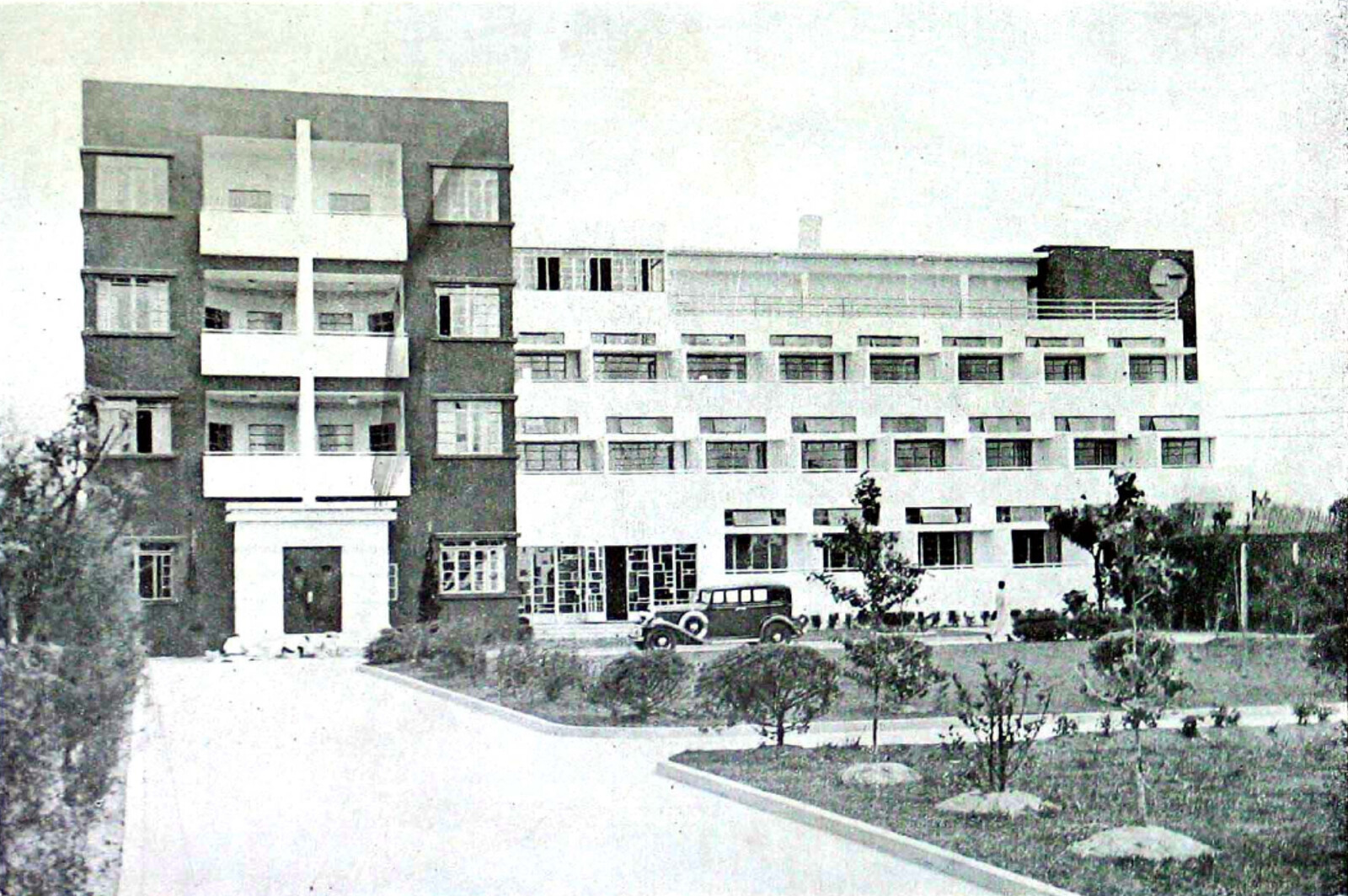

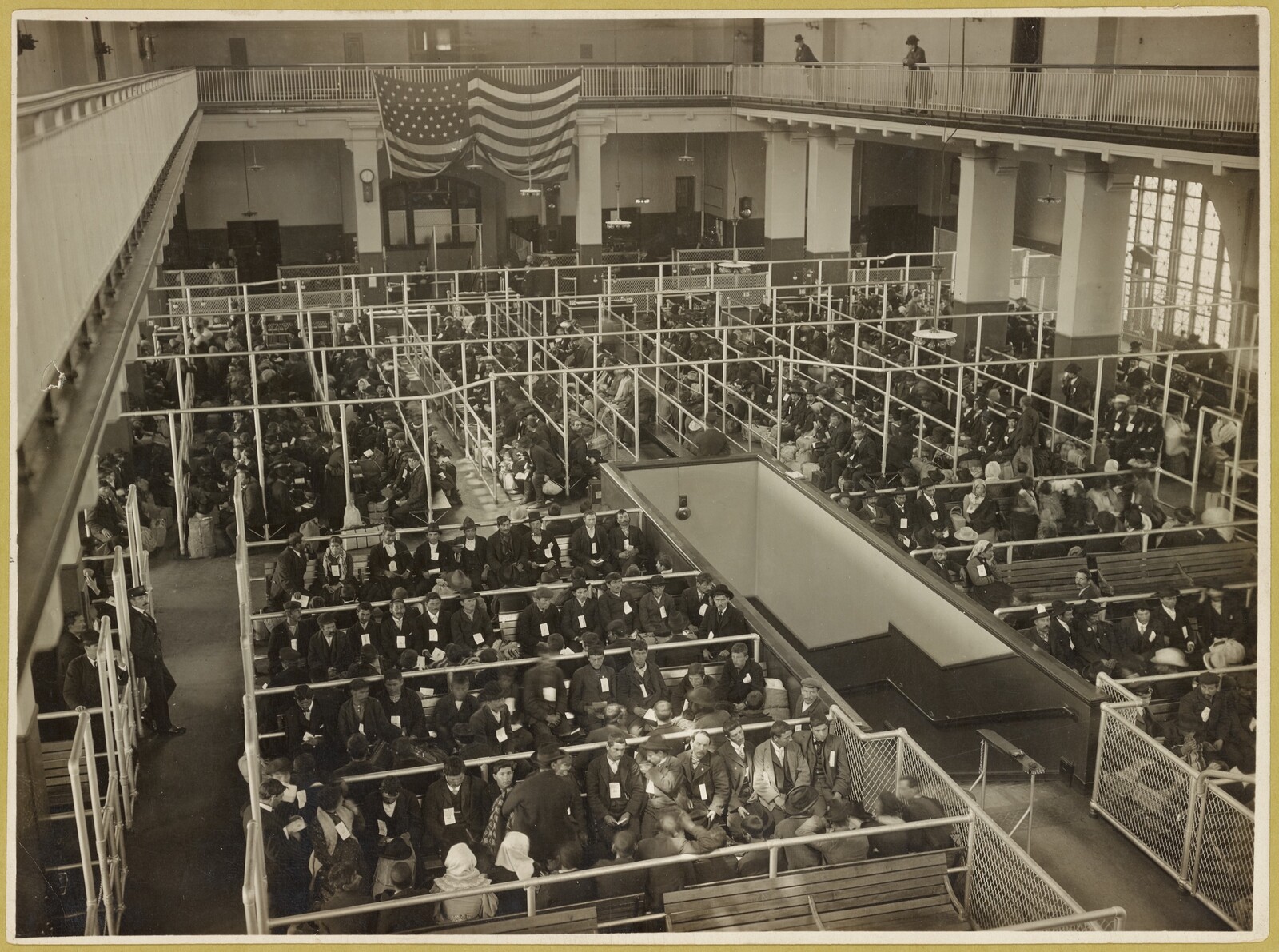

The oeuvre of the station’s architect, Walter J. Mathews, was limited to Bay Area municipal buildings when he received the station commission, but Mathews conducted considerable research for the project. The architect visited warehouses used as immigration detention barracks on the mainland and traveled to Ellis Island to observe the main station building completed there just four years earlier.11 This new complex inspired Mathews, who modeled Angel Island on its East Coast predecessor by organizing the station in a similar “cottage system” of multiple buildings, each devoted to a single purpose: hospital, barracks, powerhouse, and administration. The result is Ellis Island’s typology scaled down to suit a smaller port of entry and realized on a tighter budget ($250,000 for the entire complex vs. $1.5 million for Ellis Island’s main building alone).12

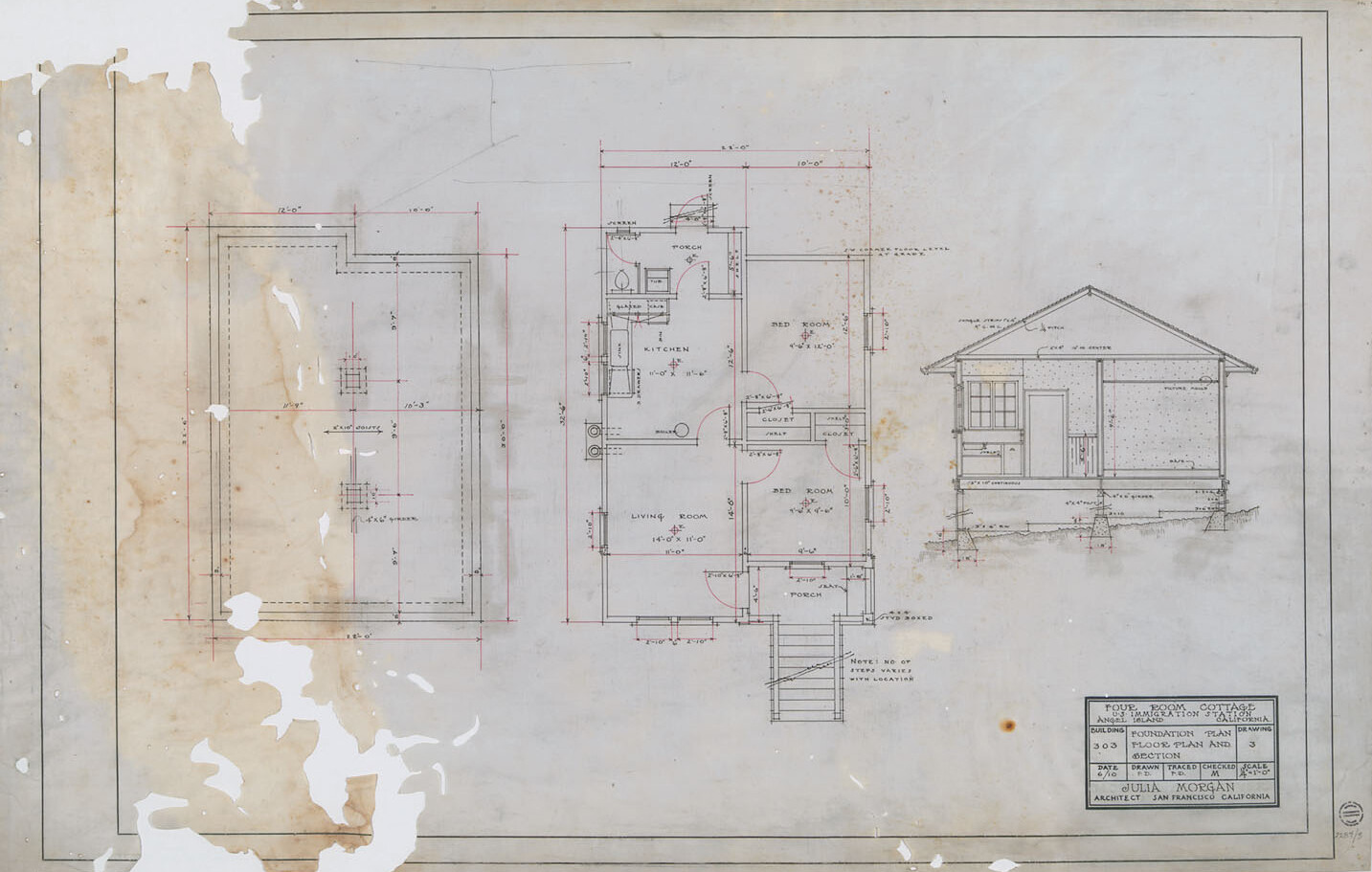

Julia Morgan’s spartan staff cottages allowed station workers to live on the island rather than take the ferry daily. Julia Morgan, Four Room Cottage Foundation, Plan, and Section. Source: Julia Morgan/Forney Collection, UC Berkeley Environmental Design Archives.

Angel Island’s designers were not entirely low-profile, however. After its opening, Julia Morgan designed staff cottages that relieved workers from travelling to the island each day, and a disinfection room that streamlined the hospital’s operations. Morgan was already well-known in California at the time for her work with the Hearst family and Mills College. Angel Island’s attraction of such a prominent architect might be explained by her personal connection to station commissioner Hart Hyatt North, her sister’s husband.13

Railings divided the main examination room into pens according to race and gender. Angel Island Immigration Station entry & main examination room, 1910. Source: National Archives and Records Administration.

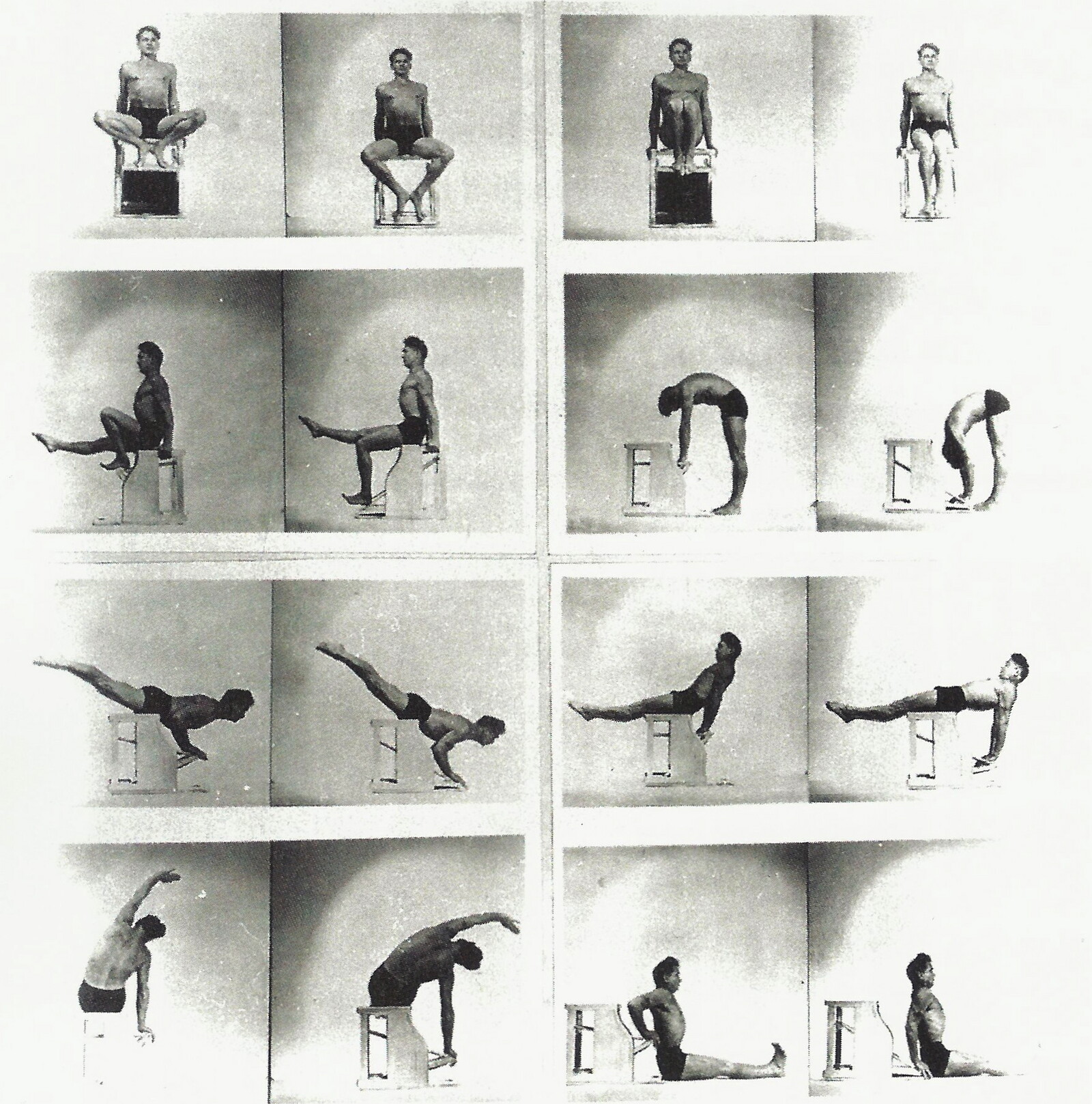

After depositing their luggage at the dock and stepping over the administration building’s windswept threshold, passengers entered a carefully calibrated architecture of immigration. A main hall divided into four metal pens divvied up passengers based on race and gender. Officers took the most visibly ill aside here but only examined them after processing. The remainder continued down four metal corridors inside a registry room so that station staff could individually observe each person. Based on new arrivals’ race, class, and profession, officers decided their fate: detention or passage to the mainland.14

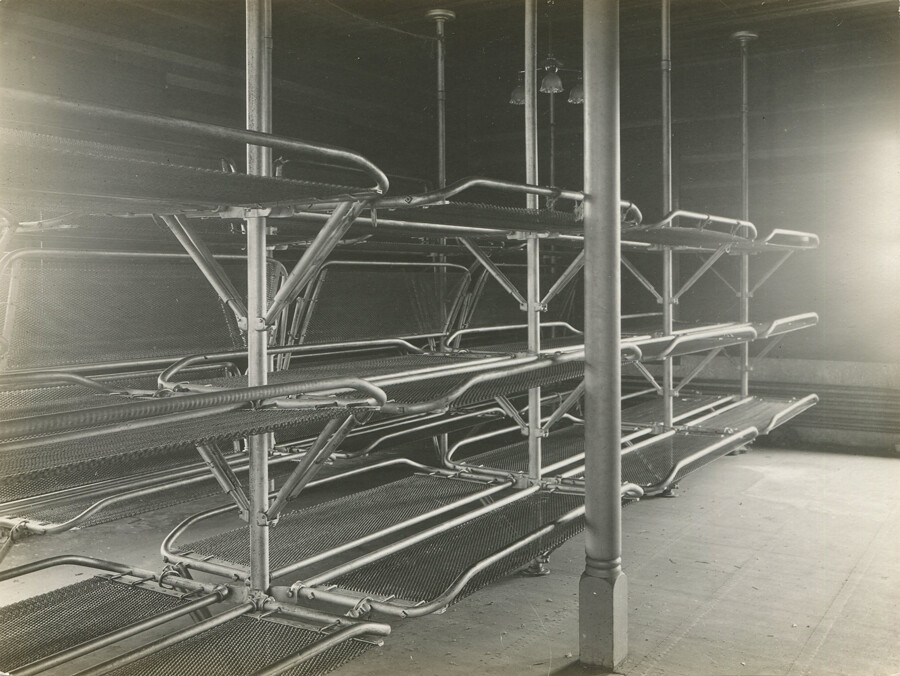

Immigrants slept in bunks stacked three high, directly adjacent to another stack of bunks on one side and a narrow walkway on the other. Angel Island Immigration Station barrack beds, 1910. Source: National Archives and Records Administration.

Those detained traveled further into the station apparatus, where spaces reinforced strict hierarchies. Europeans were lodged on the administration building’s second floor while station officials kept Asian immigrants in separate barracks. These buildings held separate wards each for Chinese men, Japanese, and other Asian men, Asian women, and federal prisoners. But despite the Chronicle’s optimism, the barracks could not hold half of the two thousand arrivals predicted for any one time. While the newspaper claimed the European accommodations were on-par with a first-class hotel, it judged the Asian barracks simply “sanitary.” Europeans washed with freshwater supplied by barge, while the showers in the Asian barracks pumped in saltwater from the bay.15 Any attempt at sanitation would have been hard in practice when the Asian barracks, designed to sleep 192 detainees at a time in bunks stacked three beds high, often hosted between three and four hundred men.

.The Asian dining room, unlike its European counterpart, had no tablecloths, lower quality silverware, and cheaply cooked meals. Chinese & Japanese Dining Room, 1933. Source: San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library.

At the time, California did not legally enforce segregated dining in the same way as the Jim Crow South, but historians have noted that many Chinese knew of and avoided establishments where staff would not serve them.16 They learned this self-segregation through the experience of dining at Angel Island so that the law did not have to enforce it later on. The four dining rooms were segregated between Europeans, Asians, staff, and visitors, and contracted firms could spend fifteen cents per European meal compared to fourteen cents per Asian while providing the latter fewer options. Distinctions continued into the décor: the European dining room had tablecloths while the Asian dining room did not.17

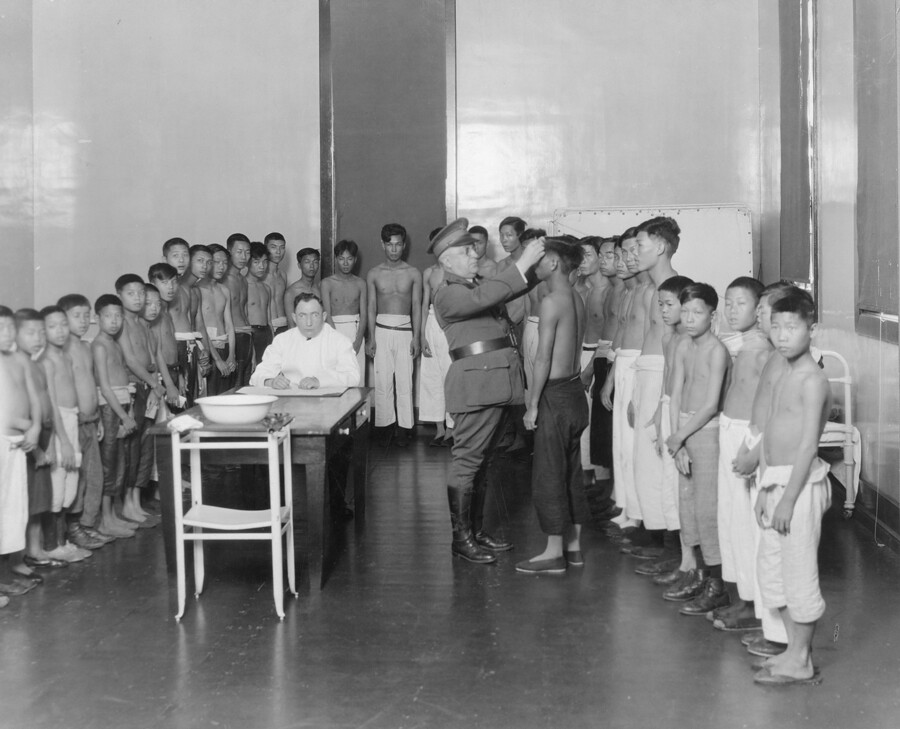

An officer performs an eye examination on a child. Western Photo Company, 1923. Source: National Library of Medicine.

Hugging the slope behind the administration building, the station’s hospital provided examination rooms where white men and women remained clothed while doctors undressed Chinese men to examine their bodies for physical abnormalities. A chief cause of deportation was a diagnosis of trachoma, a degenerative eye disease, which despite a higher prevalence in European arrivals was diagnosed more in Asians.18 The station’s medical staff also made non-contagious hookworm, threadworm, and liver fluke, all parasites common in China, into deportable diagnoses.19

The segregated nature of medical examination reveals its intent to limit Chinese immigration rather than strictly keep disease out of the United States. In fact, the hospital did little to limit disease. Its facilities even encouraged transmission. In 1914, for instance, twenty-nine detainees caught cerebrospinal meningitis from a single case. A Public Health Service report published on the outbreak in 1921 revealed that though the first cases originated in the hospital, much of the spread occurred in overcrowded barracks.20

Inside the administration building, a wing of investigation rooms held officers tasked with disproving arrivals’ claims of profession and familial relation to existing US residents. Many claims were fabricated; a lack of records at arrivals’ points of origin and the burning of birth records during the San Francisco Earthquake of 1906 enabled Chinese immigrants to trick administration officials. However, even true relatives languished in an investigation process that involved extensive minutiae designed to trick anyone, regardless of status. Viewed together, the investigation wing and the hospital constructed twin systems of examination, both personal and physical, to impede or exclude as many as possible.

Though Angel Island housed vastly more men, the experience of women on the island gives insight into the station’s reinforcement of gendered concepts of labor and family. Interrogations of women were particularly invasive and designed to reveal sexual immorality.21 Due to their small numbers, Michi Kawai, General Secretary of the YWCA of Japan, noted in a 1915 report on the island that Asian and European women dined together. Yet, this proximity revealed their distinct treatment; she made note that the “Europeans have meat, beans, and even better silverware.”22

In addition to testimony like Kawai’s, detainees criticized their treatment by writing vivid poems on the barracks’ wooden walls, some scrawled in ink or pencil and others inscribed in an elegant classical Cantonese technique. One detainee recounted:

I have been imprisoned on Island for seven weeks.

In addition, I do not know when I can land.

It is only because the road of life has many twists and turns

That one experiences such bitterness and sorrow.

Attempts at resistance also included the formation of the Zizhihui, or Self-Governing Association, in 1922 to advocate for better living arrangements. Older members of the Zizhuihui educated new arrivals on how to survive the immigration station, collected money, purchased books, held meetings, and coached detainees through their immigration investigations.23

Not every Chinese immigrant passing through Angel Island underwent the same brutal system; the Chinese Exclusion Acts allowed the wealthy to enter relatively unscathed. IM Pei, for instance, left the station the day he entered, his Notice of Admission declaring that his father, a manager of the Bank of China, could support him; that he held a telegram proving his acceptance to the University of Pennsylvania; and that he had an American reference to support him in travelling from San Francisco to the East Coast.24

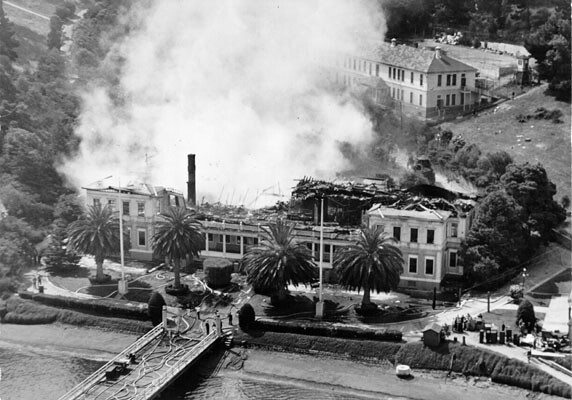

The administration building caught fire in 1940. Though the other structures remained, the station closed shortly afterward. Source: San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library.

The station quickly fell into disrepair. A US Immigration Bureau representative called it a “veritable firetrap” in 1922, just twelve years after its opening.25 Morgan’s worker cottages and hospital renovations made it moderately more functional, but the Immigration Bureau representative’s evaluation proved accurate when the administration building burned down in 1940. Coinciding with the beginning of World War Two and a need for healthier diplomatic relations between the United States and China, the station officials transferred Angel Island’s last detainees to the mainland and shut down the operation.

Following the station’s decommissioning, local conservationists formed the Angel Island Foundation and, in partnership with private boaters represented by the California State Marine Parks and Harbors Association, advocated for the island’s conservation. In 1947, the California legislature hired Frederick Law Olmsted Jr to evaluate the island. The landscape architect again looked to New York for architectural inspiration, suggesting that Angel Island could offer a recreational opportunity for San Francisco on par with what the “States of New York and New Jersey jointly have long been providing … at the Palisades Interstate Park.” Olmsted suggested that the island’s structures be repurposed for lodging tourists while warning that uses including prisons and hospitals would ironically “seriously impair the recreational values of the adjacent lands.” Two decades later, a 1966 report by Marshall McDonald and Associates acknowledged the building’s difficult pasts, suggesting demolishing all structures at the immigration station save for the barracks and hospital, which would be renovated into contemporary museum spaces.26

The difficult past represented by the immigration station’s abandoned buildings conflicted with transforming the island into a space of leisure. This was highlighted in 1970, when park ranger and San Francisco State College student Alexander Weiss visited the barracks in 1970 ahead of their proposed demolition and discovered the hundreds of poems carved by former detainees into the wooden walls.27 These poems, an unmatched evidence of the trauma experienced, were brought to light during a time of emergent Asian American political consciousness. Weiss brought the poems to the attention of his professors, who in turn shared them with Ethnic Studies faculty, who were only recently hired in the aftermath of the Third World Liberation Front’s 1968 march and the foundation of the first School of Ethnic Studies in the nation.28

Local preservationists and activists, many of them descendants of former detainees themselves, then advocated for the stabilization of the barracks building and its poems. In 1978, a $250,000 grant from the State of California allowed architect Philip Choy to make fire and accessibility code improvements on the barracks and to reinforce the poem-laden walls with seismic bracing. Choy was resolute that the preserved barracks not be reappropriated into a rosy narrative of opportunity, telling historians Erika Lee and Judy Yung that he wanted “none of this tourist stuff.”29 Instead, the preservation effort would expose the brutal conditions of the barracks: walls, floors, and ceilings were left rough, and a few remaining bunks were outfitted with personal items.

Today, visitors can visit the barracks building, where the Angel Island Immigration Station Foundation has furnished examples of the original bunks. Carol Highsmith, Angel Island Immigration Station detention barracks, 2013. Source: Library of Congress.

This first wave of preservation work attempted to relay the psychological trauma of the barracks to visitors and allow those who had experienced this trauma themselves to reenter. Former detainees who returned had a visceral experience. Richard Lee told the Chronicle that the sounds of guards rapping the bunk posts still rung in his ears; Paul Chow told The New York Times that he saw his father, Wan Gai Chow, cry for the first time upon their return visit.30 Others found catharsis in returning of their own accord. Li Kei Wong’s writing teacher encouraged her to face the station, and in doing so, found the confidence to write her memoir, Good Fortune: My Journey to Gold Mountain.31 The opening of the barracks also introduced the island to a second generation of preservationists and activists, some of whom did not even know of their own families’ connection to the island prior to its reopening.32

A common shorthand for the Angel Island Immigration Station is “the Ellis Island of the West,” but this false equivalency downplays Angel Island’s brutality. Ellis Island detained twenty percent and deported two percent of its largely European population. Angel Island detained over half and deported one in five of its largely Asian population. An Ellis Island of the West did in fact exist on Angel Island, it was just found on the other side of a wall, upstairs or downstairs, or on the opposite side of a dining room; manifested in differences at the level of a tablecloth, silverware, shower water, or the interrogation table.

The imbalance between the two sites continues into the present. Though Angel Island prominently displays a plaque noting the “Sister Park” status of Ellis Island, the plaque’s language makes clear that Ellis Island is a national park while Angel Island is only a state park. A dedicated ferry takes tourists to Ellis Island and the Statue of Liberty; visitors to Angel Island board a ferry mostly used by passengers seeking recreation, and the private company that operates the only route submitted a petition to suspend all service in December 2020.33

Nonetheless, the preservation and dissemination of Angel Island’s legacy provides an opportunity for what Viet Thanh Nguyen has termed “just memory” when he writes that “any project of the humanities … should also be a project of the inhumanities, how civilizations are built on forgotten barbarism toward others.”34 Demonstrating this potential, in 2003 Angel Island’s travelling exhibition Gateway to Gold Mountain opened at the Ellis Island Immigration Museum with a lion dance performed by students from the Chinese Community Center of New Jersey. In doing so, it argued for inclusion of those historically excluded from the wider narrative of American immigration. Local papers described Asian American visitors seeing their own stories in the museum for the first time.35 Speaking to the press, Ellis Island’s curator of exhibits and media maintained that the exhibition “enables us to tell the larger story.”36 As an antidote to the mythologies of Ellis Island and American immigration, the preservation and dissemination of Angel Island demonstrates that architectures of exclusion existed on both shores and were unequally applied along lines of race and class, with disease labeled as the culprit.

Until I boarded a ferry to Angel Island myself this past summer, I had not fully understood the geographic isolation of the immigration station. The ferry trip from San Francisco to the island today takes about thirty minutes, though the journey would have been longer one century earlier. High waves and strong winds and coming off the Pacific buffeted the boat as the San Francisco skyline faded behind fog. I went to Angel Island assuming I would find little personal connection to it. My father and grandmother had flown from Seoul to San Francisco long after the immigration station shut down, and I had always assumed that the one great grandfather who had left Korea to pursue a graduate degree in New York had passed through Ellis Island unscathed just like my Ashkenazi Jewish great grandparents had done around the same time. Reading about Pei’s itinerary prompted me to double check my great-grandfather’s immigration records. To my surprise, Chough Pyung-Ok had not only been detained at Angel Island but had been treated for hookworm in the station’s hospital at a cost of all of the money he had brought with him.

I struggled to reconstruct what his experience would have been. The immigration station sits on the island’s far north shore, completely out of sight of the cities that line the Bay. New arrivals were truly alone, with vast stretches of wind and water separating them from where they had left, where they hoped to go, and anyone who would have aided them on either shore. Chough was among those more privileged; his records also noted that a white missionary, MC Harris, accompanied him from Yokohama, undoubtedly helping his case.37 Coming from Korea via Japan, he was subject to a different set of immigration standards set by a Gentleman’s Agreement between the United States and Japan that relied more on exclusion at his port of departure. Finding him personalized the distinction between Angel Island and Ellis Island for me. While my Eastern European family could arrive in New York via steerage with little network in the United States, Chough could only enter the country via wealth and connections to whiteness. And even in his privileged position, he still entered the country marked as diseased.

Covid-19 revealed what many Asian-Americans already understood: that a country could simultaneously refer to itself as a nation of immigrants and mark some immigrants perpetually dangerous. If an Ellis Island of the West existed, it comprised just one part of a larger immigration apparatus that gave out vastly different treatment based on race, setting a precedent for an immigration system that continues to separate and detain migrant families from non-white countries. Thus, the political potential of the preservation of Angel Island and similar sites is reparative. Preserving its legacy does not merely bring more groups into a popular understanding of the United States as a “nation of immigrants,” but rather redefines the United States as a nation produced by exclusion.

Yao Lu et al., “Priming COVID-19 Salience Increases Prejudice and Discriminatory Intent against Asians and Hispanics,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 118, no. 36 (September 7, 2021).

“Pelosi Remarks at Media Availability Following Visit to San Francisco’s Chinatown and Meetings with Local Business Owners: Press Release” (Office of the Speaker of the House, February 24, 2020), https://www.speaker.gov/newsroom/22420. Lisa M. Krieger, “Coronavirus: Where Did All Our Old Quarantine Facilities Go?,” The Mercury News, February 24, 2020, ➝.

Luigi F. Lucaccini, “The Public Health Service on Angel Island,” Public Health Reports (1974-) 111, no. 1 (1996): 92.

Lucaccini, “The Public Health Service on Angel Island,” 92.

Michael C. LeMay, Doctors at the Borders: Immigration and the Rise of Public Health: Immigration and the Rise of Public Health (ABC-CLIO, 2015), 101.

Arthur B. Stout, Chinese Immigration and the Physiological Causes of the Decay of a Nation (Agnew & Deffebach, 1862).

“Untitled Article (“The Anti-Chinese Convention Has Adjourned…),” The Daily Alta California, March 14, 1886, California Daily Newspaper Collection, UCR Center for Bibliographical Studies and Research.

Grover Cleveland, “October 1, 1888: Message Regarding Chinese Exclusion Act,” Presidential Speeches | Miller Center, University of Virginia, October 20, 2016, ➝.

Though Chinese immigrants were the most targeted, arrivals from other Asian countries and some Europeans were subject to similar, though not as stringent systems of segregation, detention and deportation, as the station aged. Future uses of “Asian” in place of “Chinese” refer to instances in which all Asian immigrants, not just Chinese, were subject to specific conditions. See Erika Lee and Judy Yung, Angel Island: Immigrant Gateway to America (Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press, 2012), 4.

Louis Stellmann, “San Francisco to Have the Finest Immigrant Station in the World,” San Francisco Chronicle (1869-Current File), August 18, 1907.

“Metcalf to Make Inspection Tour,” San Francisco Examiner, September 28, 1904.

Statue of Liberty National Monument (N.M.) and Ellis Island, Ellis Island Development Concept Plan: Environmental Impact Statement, 2005, 5.

“US Immigration Station, Angel Island, USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form” (National Historic Landmarks Survey, National Park Service, October 15, 1995), 4, National Register of Historic Places.

While detention and deportation were overwhelmingly applied to Chinese immigrants under the Chinese Exclusion Acts, the apparatus was applied in increasing cases to other Asians and Europeans in later decades of the station’s operation. In particular, the 1924 Immigration Act established quotas on immigrants from many countries aside from China, who were also detained or deported if the number of arrivals already processed from their country of origin had already reached their countries’ quotas. See Lee and Yung, Angel Island.

Stellmann, “San Francisco to Have the Finest Immigrant Station in the World.”

Beth Lew-Williams, The Chinese Must Go: Violence, Exclusion, and the Making of the Alien in America, 1st Edition (Cambridge, Massachusetts; London, England: Harvard University Press, 2018), 110, 230–231.

Lee and Yung, Angel Island, 61.

Lee and Yung, Angel Island, 39.; Stellmann, “San Francisco to Have the Finest Immigrant Station in the World.”

Him Mark Lai, “Island of Immortals: Chinese Immigrants and the Angel Island Immigration Station,” California History 57, no. 1 (1978): 94.

Joseph Bolten, Cerebrospinal Meningitis at Angel Island Immigration Station, Calif (Public Health Reports (1896-1970), 1921), 593–594.

Lee and Yung, 22.

Michi Kawai, “A Day on Angel Island,” Joshi Seinen-Kai 12, no. 8–9 (September 1915): 49–53.

Him Mark Lai, “Island of Immortals”: 97.

“Pei, Ieoh Ming - Case Number: 35527/015-16” (Department of Justice, Immigration and Naturalization Service, San Francisco District Office, August 28, 1935), 35527/015-16, National Archives at San Francisco (RW-SB).

“Immigration Station Needs Pointed Out: Elimination of Disease and Greater Efficiency Will Follow,” San Francisco Chronicle (December 20, 1922).

Frederick Law Olmsted, Jr., “Report on the Recreational Possibilities and Values of Angel Island, San Francisco Bay,” 1947, Angel Island Foundation Committee Records, 1950-1966 vol. 1, UC Berkeley: Bancroft Library; Marshall McDonald, “Recommendations for the Historical Recreational Development of Angel Island,” 1966, Him Mark Lai Papers, Box 2, Folder 4, UC Berkeley: Ethnic Studies Library, Asian American Studies Archives.

Him Mark Lai, Genny Lim, and Judy Yung, eds., Island: Poetry and History of Chinese Immigrants on Angel Island, 1910-1940 (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2014), 19.

Karen Umemoto, “‘On Strike!’ San Francisco State College Strike, 1968–69: The Role of Asian American Students,” Amerasia Journal 15, no. 1 (January 1, 1989): 25.

Lee and Yung, Angel Island, 307.

Katherine Bishop, “Angel Island Journal: Saving Voices of the Other Ellis Island,” The New York Times, November 11, 1990.

Patricia Leigh Brown, “Poetic Justice for a Feared Immigrant Stop,” The New York Times (December 7, 2005), ➝.

Notably, the descendants of detainees were affected by the site’s preservation, though in different ways than their parents and relatives. This perhaps demonstrates what Marianne Hirsch has termed “postmemory,” or a remembering of trauma of generations before, passed down both directly and indirectly, as well as the “reading of silence” Gabriele Schwab identifies in such a “post-generation.” Hirsch, The Generation of Postmemory, 6.

Carly Graf, “Some San Francisco Ferries Could Stop Running to Angel Island and Tiburon,” The San Francisco Examiner (December 20, 2020), ➝.

Viet Thanh Nguyen, Nothing Ever Dies: Vietnam and the Memory of War (Cambridge, Massachusetts; London, England: Harvard University Press, 2016), 19.

Merry Firschein, “Angel Island, the Other Ellis Island - Exhibition Tells the Story of Chinese Entry in California,” The Record (Hackensack, NJ) (March 9, 2003).

Corey Takahashi, “West Coast Legacy Of the ‘Paper People,’” Newsday, accessed December 16, 2020.

“Cho, Pyeng Ok - Case Number: 13203/012-02,” China Passenger January 26, 1914; Immigration Arrival Investigation Case Files, 1884-1944. Record Group 85: Records of the Immigration and Naturalization Service, 1787-2004.

Sick Architecture is a collaboration between Beatriz Colomina, e-flux Architecture, CIVA Brussels, and the Princeton University Ph.D. Program in the History and Theory of Architecture, with the support of the Rapid Response David A. Gardner ’69 Magic Grant from the Humanities Council and the Program in Media and Modernity at Princeton University.