Sylvia Rivera’s Home

On the bleak spring morning of April 6, 1996, the TV station WPQG interviewed Sylvia Rivera at her home in New York. The camera focused on her rescued plants, her plush bear toy, her salvaged furniture, her little altars with photographs of her chosen family, and her outfits hanging in the improvised walls of her shack—a fragile structure made with broken doors, some plastics, and cardboard. Rivera’s home was in Lower Manhattan at Pier 45, which faced the Hudson River on one side and the wrecked West Side Highway on the other, at the very end of Christopher Street. After a brief period away from Manhattan, Sylvia came back to the piers in 1992, when the body of her friend, the African American sex worker and activist Marsha P. Johnson, was found floating in the Hudson on July 6.1 It was the place where Rivera labored for decades as a sex worker, lived, and socialized with other members of the LGBTQIA+ community (mostly racialized, gender non-conforming people like herself), and the “homeless” population that actually found a “home” on that piece of land.2

Rivera was a Puerto Rican trans activist who changed LGBTQIA+ history through her involvement in the Stonewall riots and her fight for the rights of sex workers, incarcerated people, and the homeless. Her house, along with a dozen other dwellings where more than thirty people lived, was destroyed that morning in 1996 by the Hudson River Park Conservancy, a subsidiary of the New York State Urban Development Corporation as part of the clearance operation to build the Hudson River waterfront (from Battery Park City to 59th Street). The Hudson River waterfront project, designed by Quennell Rothschild Associates/Signe Nielsen, included a boulevard, trees, a seven-lane highway, and paths for bikers, joggers, and skaters. Designed as a continuous extension of greenery, the park buffered the presence of the highway, an infrastructure intended to complete the large-scale plan of facilitating the daily commute of white-collar workers to and from the suburbs and their single-family detached dwellings. The New York State Urban Development Corporation saw in the piers a sacrificial milieu of impurity and devaluation. Rivera described the event as follows: “It’s called a sweep. Not even a fucking eviction. A sweep, like we’re trash.”3

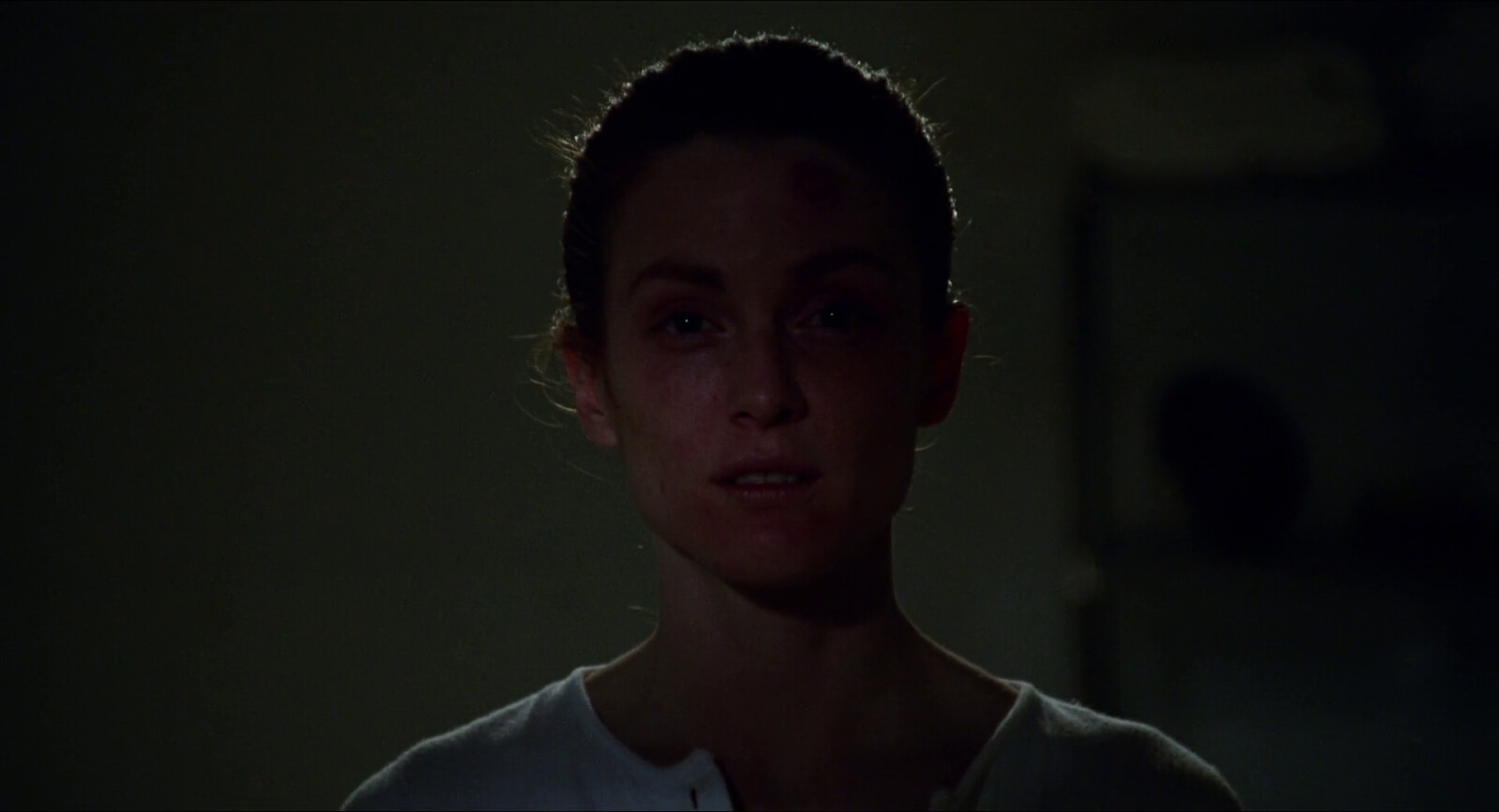

Sylvia Rivera at her home in 1996. Courtesy of Valerie Shaff.

The clearance operation of the piers took place under the New York Slum Clearance Commission and Law and its frothy utopian verbiage of “sanitizing” an environment that was referred to as dangerous, unhealthy, insalubrious, and unsuitable for human life. “For more than a year,” one report about the Commission wrote, “people who live in apartments near the homeless colony have complained of rotting trash, stray cats, and bonfires smoldering in the night.”4 But for Rivera that was just an excuse, epitomized by a Thanksgiving dinner they organized years before that was shut down by the New York Police Department (NYPD), when neighbors complained they were cooking a turkey and pumpkin pie in an oven made from a file drawer and a fire. The neighbors were disgusted, but for Rivera, “these guys, they might just look like dirty homeless people to you, but to me, they were my family.”5

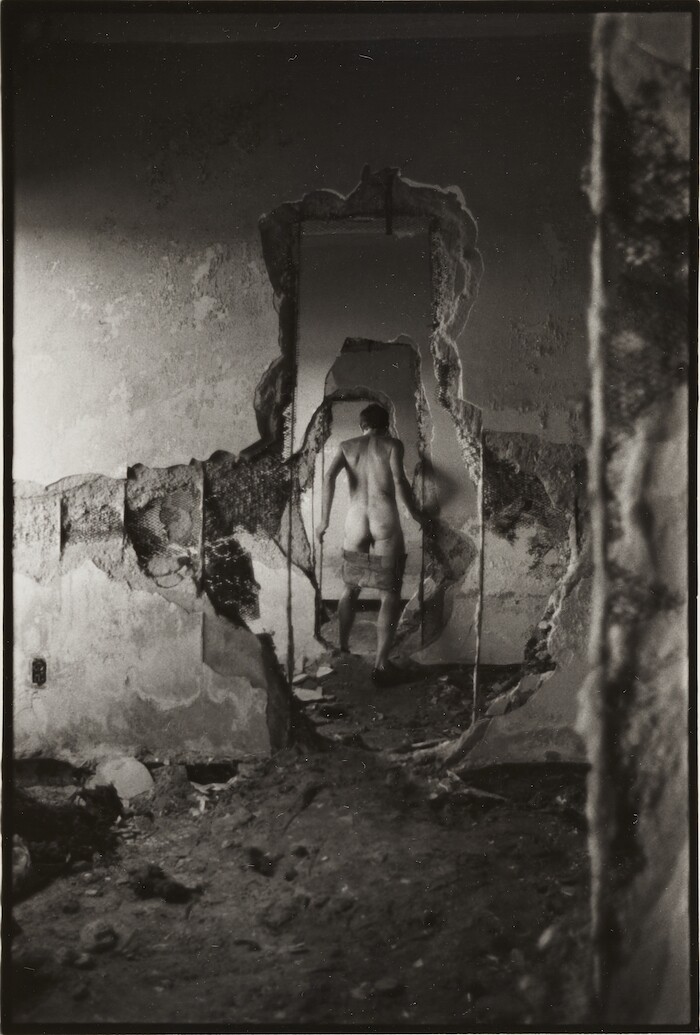

Sylvia Rivera at the piers in 1996. Courtesy of Valerie Shaff.

The demolition of the piers showed the violent clash of two confronting forms of urbanism, radically differentiated by the way they shaped collective contagiousness. For Rivera and her community, the piers were a place where bodies and a riverfront architecture turned permeable by the accumulative effect of decay, wall-cutting, makeshift additions, and material abandonees were entangled as interconnected components of a single medium constituted by material porousness. The second form of urbanism, promoted by the Hudson River Park Conservancy, was exemplary of the growth of the petrochemical industry that since the 1940s established an oil-based territoriality: encapsulated humans placed in distant and segregated suburban, car driven, and family-block-based milieus. The former came from the understanding of the piers as a relational system based on non-binary transness and mutual dependency.6 Meanwhile, the latter was based on a prophylactic view that considered the piers as a promiscuous, disease-driven space that had to be erased. Before their redevelopment, the piers were “dirty” because they were porous, contagious, permeable to otherness: to the otherness of other human bodies; to the otherness of an environment and its decaying architecture; to the otherness of saliva, blood, and semen.

Blight City

Since the 1910s, the Christopher Street piers were synonymous with queer cruising. The multiple buildings of the shipping companies located in the area, with their dark, hidden spots populated at night by men who had sex with men, were the perfect place for sexual encounters otherwise prosecuted under the sodomy laws of New York State. With the forfeit of the piers by the army and ocean liners after 1945, the progressively derelict infrastructures intensified their life as a complex ecosystem and institutions for alternative ways of living, including multiple bars in the adjacent West Village, from the Stonewall Inn and Julius’ to the leather-friendly Ramrod and Keller; community spaces, from the Women’s Liberation Center to The Center; bookstores like Labyris; and queer associations like the Mattachine Society.

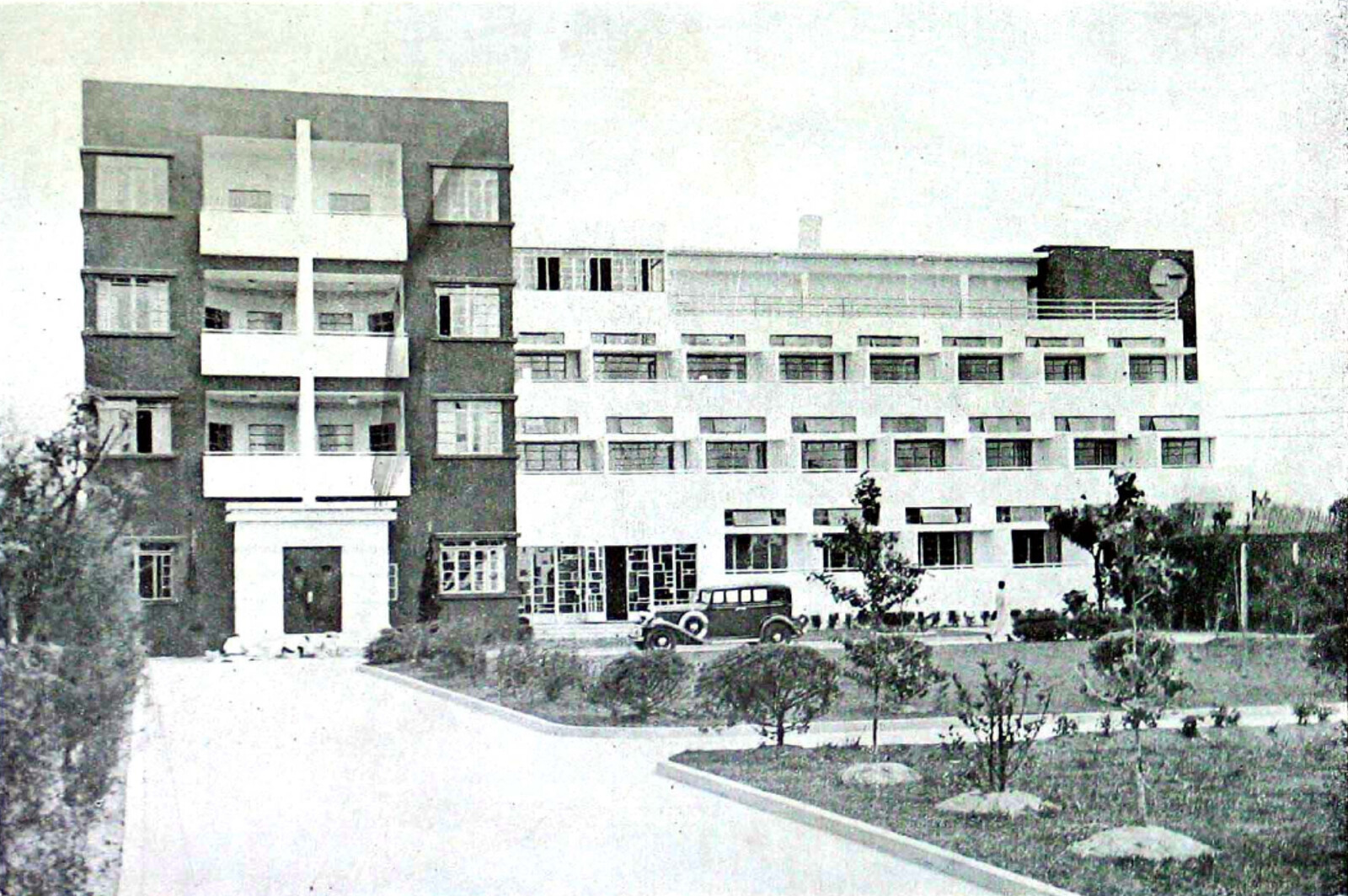

The piers were neither alone in the creation of an ecosystem that allowed alternative ways of living to flourish, nor in their description as an unsanitary and boorish environment. Downtown Manhattan at large was known during the 1960s as “the Wastelands of New York,” an epithet that came from the immense body of manufacturing buildings abandoned during the city’s deindustrialization in the 1970s and 1980s.7 This was accompanied by a recession that hit the city especially hard in the late 1960s, when its working class industrial base was transformed into a corporate and service-based economy and New York State Governor Nelson A. Rockefeller, together with city planners, implemented policies to frame Manhattan as a place for work, but not living. As former director of Creole Petroleum, proposals spurred through Rockefeller’s mandate (1959–1973) took the private car as the center of urban development. The car encapsulated the human body, allowing it to get into the city from the suburbs and park in a garage at the office (as buildings like the Lever House or the Seagram exemplified) without having to walk in the streets.8

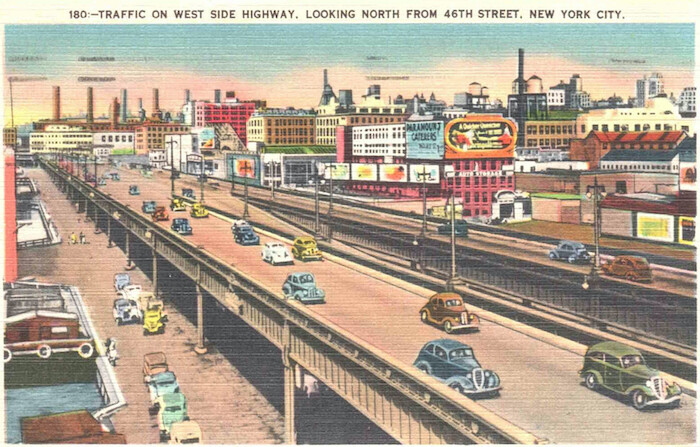

Postcard of the West Side Highway, ca. 1930.

The rhetoric used by public and private officials to get rid of the piers was embedded in medical metaphors, peculiarly using the discourse of “blight” to secure political and judicial approval for their efforts. As Wendell Pritchett explains, blight “was a disease that threatened to turn healthy areas into slums. A vague, amorphous term, blight was a rhetorical device that enabled advocates to reorganize property ownership by declaring certain real estate dangerous to the future of the city.”9 Lewis Mumford even referred to blight as a “cancer” that should be removed.10 At the same time, these discussions were imbricated with racial depictions and xenophobic targets: most of the constructions beleaguered in this operation were inhabited or used by black people, Latin Americans, migrants, and displaced communities.

Way before the Hudson River waterfront project tore down Rivera’s home, numerous plans were afloat to “cleanse” this part of the city. Already in 1941, Robert Moses proposed the infamous Lower Manhattan Express Highway (LOMEX), which would have connected New Jersey to Brooklyn and demolished large parts of SoHo, the piers, the West Village, and the Lower East Side. The project, which involved architects and urbanists like Shadrach Woods and Paul Rudolph and studies commissioned by the Ford Foundation, was only canceled in 1985, after demonstrations starting in the 1960s led by Shirley Hayes, Jane Jacobs, and the Committee to Save the West Village, among others. But from the early 1940s to the mid-1980s, the destiny of all that was in the way of LOMEX almost seemed inevitable: “Civic organizations, advocacy groups, and political actors, including Robert Moses, New York University (NYU), the City Club of New York, and the United Hatters, Cap and Millinery Worker’s Union, argued that these buildings were, at best, obsolete for modern industry and, at worst, dangerous to their inhabitants and neighbors.”11 When a section of the West Side Highway collapsed in 1973, the enterprise to get rid of the piers at the end of the Village, intensified. Videos like Gordon Matta-Clark’s Day’s End (1975) reinforced the idea that this part of the city was “empty,” just a relic from a glorious industrial past.12

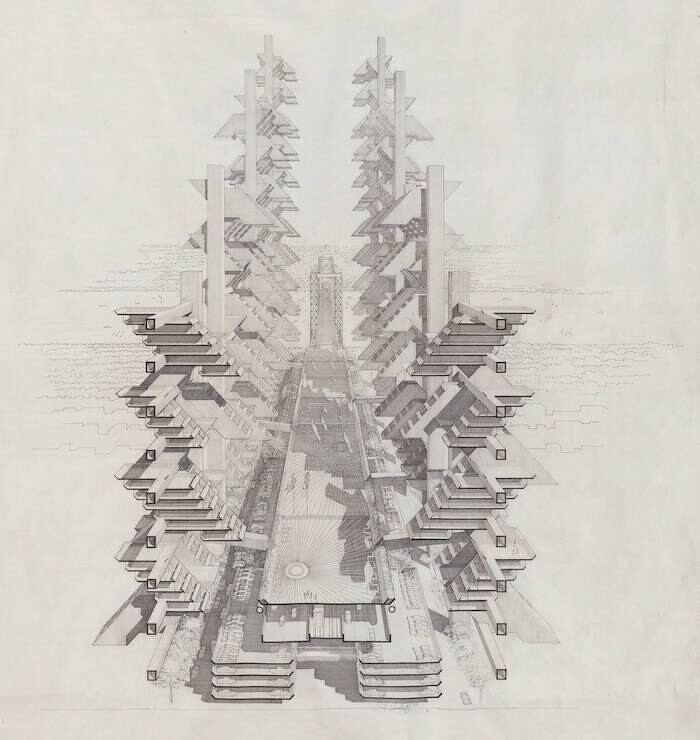

Paul Rudolph, Lower Manhattan Expressway Project, New York (Perspective to the East), 1972. The Museum of Modern Art/ Gift of The Howard Gilman Foundation.

This was, however, not the case. The piers thrived with life. As Grace Dunham pointed out, they were “a place where gay men, trans people, and sex workers all gathered to participate in social, sexual, and political life. They provided a refuge away from NYPD surveillance, which specifically targeted low-income queer and trans people and trans people of color.”13 Here this community engaged in sexual activity, sunbathed at the docks, and cared for and educated each other. They also embarked on cultural projects inspired by their environment, as is clear in the art of Alvin Baltrop, Shelley Seccombe, Rudy Grillo, David Wojnarowicz, and Leonard Fink.

The notion of the piers as insalubrious areas that needed to be wiped out gained traction in the 1980s—during the peak of the HIV/AIDS crisis—when different spaces frequented by the LGBTQIA+ community in New York (cruising areas, saunas, bathhouses, bars, nightclubs) were targeted as “public health” menaces. This categorization of an “unhealthy” environment revived the pervasive narratives of the nineteenth-century hygienist movement, which traced a false connection between diseases and the appearance of the urban environment. This narrative concerning the piers was active in New York City until the early 2000s, until Mayor Michael Bloomberg and Governor George Pataki opened the Greenwich Village segment of Hudson River Park on May 30, 2003. The highway was finally demolished, the waterfront was built, and a series of gates were erected to keep Pier 45 closed after 1am to avoid concentrations of the people that had made the piers a blooming environment years before. The previous residents of these spaces were just routine casualties.

The new proposal opted for a unitary, straightforward, apparently open but constantly surveilled set of facilities, where constant circulation (by car, skate, bike, foot) was central, and framed the conception of the piers as a passing point. This contrasted the labyrinthic and fragmented former setting, with multitudes of hidden spaces that provided a sense of privacy and safety for the persecuted queer community. It substituted a technosocial assemblage based on contagiousness—where human bodies were part of an extensive environment, shaping it and being shaped in return—for a technocratic solution—where the previous inhabitants were obliterated and erased through an urban operation that conceived their former actors and their built environment as unhealthy and useless.

STAR

The history of the piers runs parallel to the history of the LGBTQIA+ movement in New York. This is where Sylvia Rivera and Marsha P. Johnson decided to locate the first installment of Street Transvestites Action Revolutionaries (STAR) in 1970 to fight for trans sex-workers rights, a year after the Stonewall riots. Both Rivera and Johnson took an active part in this revolt, but their participation was not immediately recognized.14 Segments of associations like the Gay Liberation Front and the Gay Activist Alliance that were coordinating actions to fight homophobia in New York excluded them for being trans and “parodying” womanhood. This exclusion was galvanized during the 1973 Gay Pride Rally in New York, where Rivera tried to speak to the audience congregated in Washington Square. At the beginning, none of the organizers allowed her to do so. When she finally was able to, pushing her way to the microphone, she said: “I have been beaten. I have had my nose broken. I have been thrown in jail. I have lost my job. I have lost my apartment for gay liberation. And you all treat me this way? What the fuck’s wrong with you all?” She asked the movement to support racialized, trans sex workers and incarcerated people, instead of just focusing on cis “men and women that belong to a white middle class club.” As she was booed by the demonstrators, she was forcefully removed from the stage while still shouting “Revolution now! Gay power!”[This moment put together the “enunciated” and the “enunciation,” as Walter Mignolo would say, opening the possibility of decolonizing the LGBTQIA+ movement.]

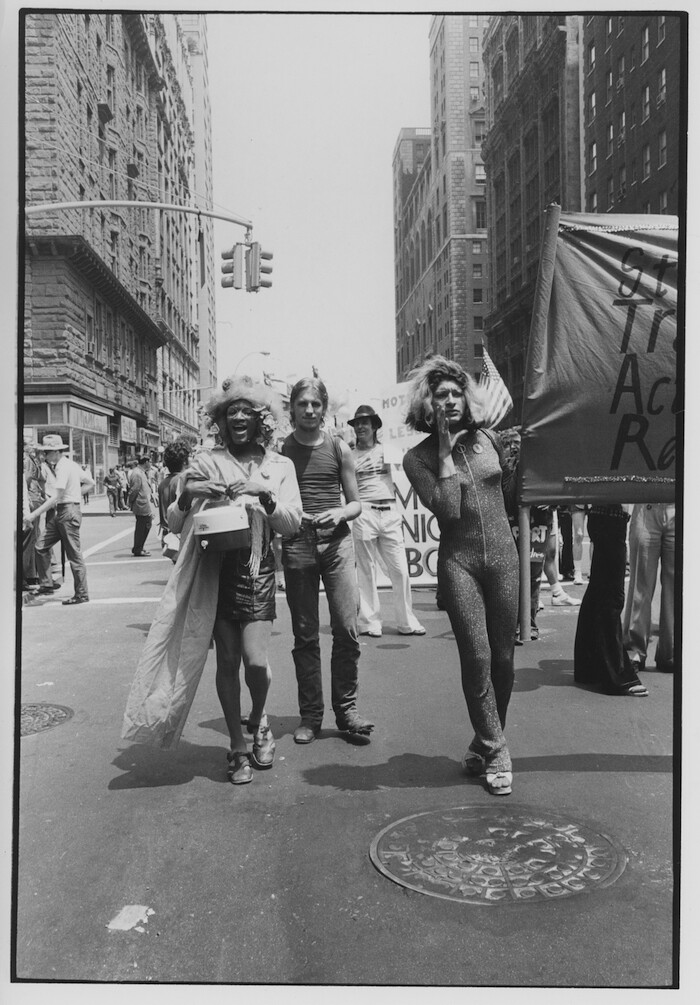

Marsha P. Johnson and Sylvia Rivera. Leonard Fink, Street Transvestites Action Revolutionaries at the Christopher Street Liberation Day March, 1973. The LGBT Community Center National History Archive.

This episode highlighted the tensions between what was happening in the built environment of New York’s wastelands and the LGBTQIA+ movement at large. Rivera and the pier community were pushing for a space of mutual dependency, a radical queer ecology that confronted the structural exclusion of people like them (gender non-conforming, racialized, sex worker, homeless). Meanwhile, the audience that congregated at Washington Square proposed what Lisa Duggan calls the new homonormativity: an ideology based on the negation of alternative forms of living and the acceptance of a heteronormative framework for the LGBTQIA+ community based on a white domestic privacy and the freedom to consume.15

Feeling left behind by the movement, Johnson and Rivera founded STAR to provide a roof and social support for underage and homeless LGBTQIA+ sex workers in New York. They first conceived of STAR as an itinerant institution inside a trailer truck parked at the piers. STAR’s van was the opposite of NYC officials’ conception of the automobile. It was not about detaching their users from their surroundings, but connecting them, to act as a medium of contagiousness that could shape a form of kin. Teenage sex workers slept inside while Johnson and Rivera worked at night, bringing back breakfast in the morning. But one day, when Johnson and Rivera approached STAR with groceries, they saw the trailer moving. Apparently, somebody reclaimed it and drove off with all of their belongings, as well as “one stoned queen” sleeping inside, who woke up several days later in California.16 They then moved STAR to an abandoned building at 213 East Second Street for a small amount of rent paid to the mob figure Michael Umbers. They renovated the building and threw parties to fundraise. But the owners of the building acted in malfeasance. After the renovations—once it was habitable—they were evicted.

A New Kin

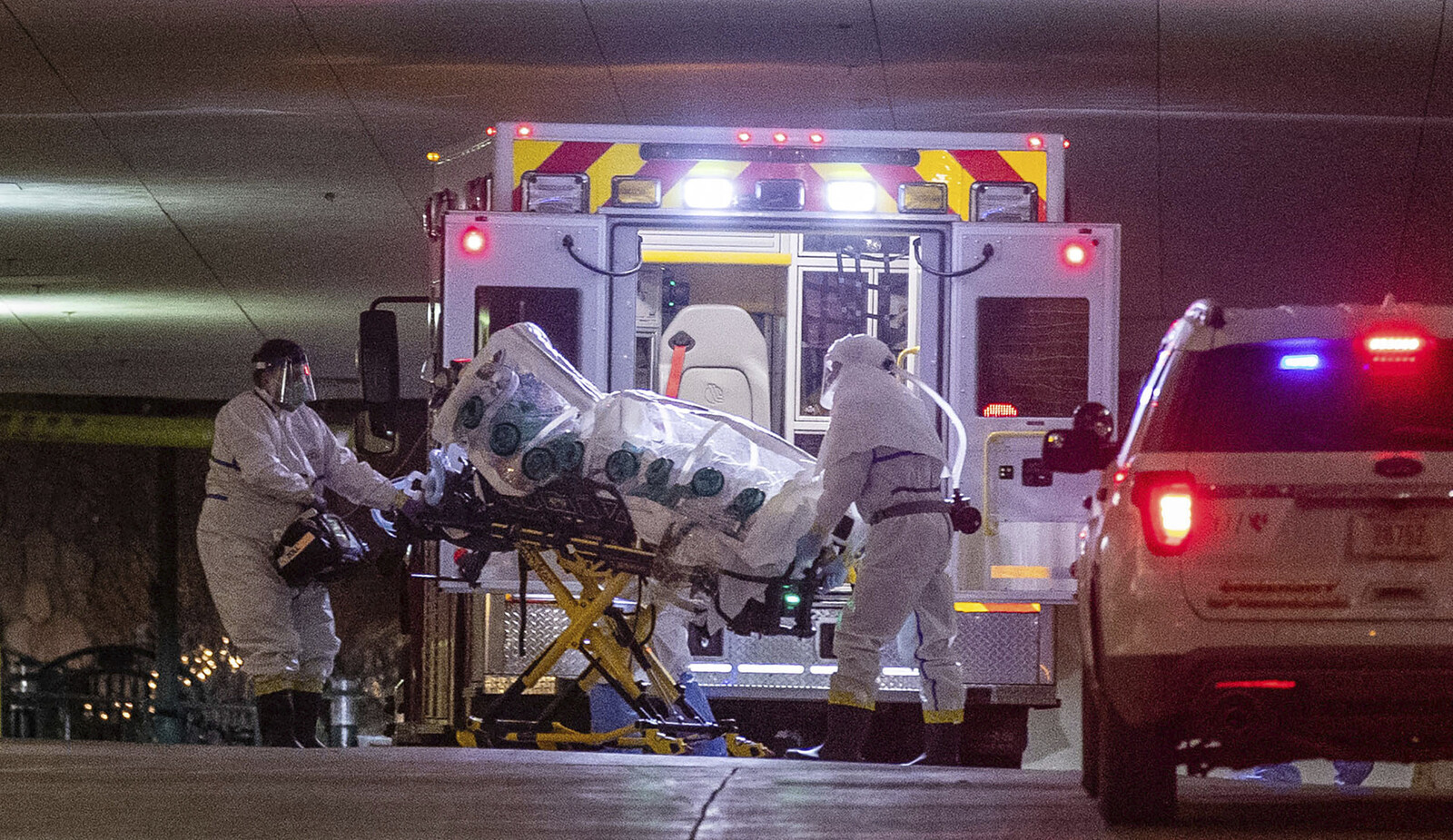

Rivera continued her fight over the years. This struggle only intensified during the HIV/AIDS crisis of the 1980s, when she advocated for the rights of sex workers, the incarcerated, and trans and homeless people, who were all hit especially hard by the pandemic. At the time, the United States government, along with the mainstream media and several health agencies such as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), sought to identify and confine potential risk groups, who came to be known as the 4H’s: homosexuals, heroin addicts, hemophiliacs, and Haitians.17 Members of these groups were ostracized and deprived of typical considerations during the outbreak of an epidemic: protocols of announcement, transparency in information, research, and measure-taking. Meanwhile, the communities that congregated around the piers, and the piers themselves, helped spread information about AIDS, made transparent the available data, and offered care among affected communities. Groups and associations like STAR, ACT-UP, Gay Men’s Health Crisis, and Gran Fury were essential in this effort. A form of kinship was created that was not based on traditional understanding of lineage (consanguinity, phylogenetic relationships, traditional family structures), but on the way they engaged with a virus (HIV) and a disease (AIDS) through activism.18

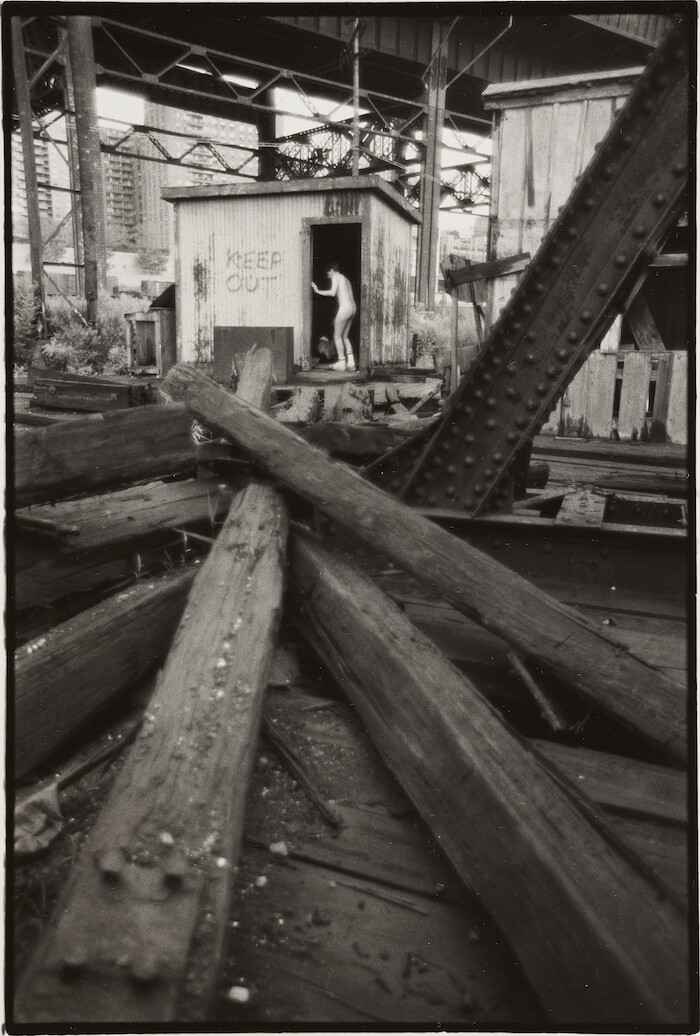

Leonard Fink, Leonard Fink Explores the Pier. The LGBT Community Center National History Archive.

HIV was the biological agent that allowed kinship to form among its carriers, acting as both kin and the apparatus by which kin was created. These ties were not only biological, but also social and political: not all of the people involved in this kinship carried the virus or shared the same positive status—and even if they shared it, there were multiple thresholds in the viral load: undetectables, HIV positive with no AIDS, false positives, etc. Thus, the bonding between community members was more than biological, escaping the dichotomy of biological/non-biological kin. What they shared was a chosen kinship: an understanding of their relationship with HIV and AIDS different from the one embraced by medical authorities, media, and government officials.19

This environmental activism, where kin was formed through the relationship between humans and non-humans (HIV) and their ecosystem, happened in places like the piers. This can be seen in the scenes of Paris is Burning (Jennie Livingston, 1990) which was partly recorded at Pier 45. Because of the relationship between queer communities, the spaces they frequented, and HIV, official institutions rapidly targeted these spaces as illicit and degrading. The piers were not unique in the way they were depicted as a menace for collective health. At a time when “men only” spaces for dancing were still illegal, and New York legislation required clubs to have at least one woman for every three men, bathhouses created a friendly alternative guised as health or cultural facilities. They were an escape from the constant scrutiny of authorities and from homophobic attacks on gay men who were caught having sex in public or private spaces around the city, and they were found everywhere: Everard at West 28th Street, St. Mark’s in the East Village, Mount Morris in Harlem. HIV/AIDS was shaped in the dispute between two urban forms of contagiousness: one that would render the pandemic into both a medium and kinship, where the spread of the virus among humans would be coupled with the relational artifacts prevention and care depended on; and another that repressed the visibility and circulation of the virus as a medium and would develop efforts to isolate it in socially stagnated, segregated capsules of marginalization.

Leonard Fink, Leonard Fink poses in the rubble. The LGBT Community Center National History Archive.

A certain environment-specific villain

The political importance of the piers, along with nightclubs, bathhouses, and saunas, and the contagious activism they sustained in the redefinition of an environmental kinship provided by the racialized trans and queer communities and the places they inhabited, was tested during the early years of the virus’s outbreak. Gay men were the face of the epidemic’s early years.20 As sociologist Steven Epstein pointed out, “AIDS became a ‘gay disease’ primarily because clinicians, epidemiologists, and reporters perceived it through that filter, but secondarily because gay communities were obliged to make it their own” with their responses and organized groups.21 AIDS’ first name, GRID (Gay Related Immune Deficiency), as well as the common “gay plague” and “gay cancer” epithets, strengthened the idea of a specifically gay disease related to a certain environment-specific villain.22 Journalists, following the views of public health authorities, blamed the epidemic on gay promiscuity and the places gay people frequented.23

This theory was adopted by doctors like Yehudi M. Felman of New York City’s Bureau of Venereal Disease Control, who declared that the disease’s cause “could be the bugs out of the pipes in the bathhouses” or poppers (amyl nitrite), a recreational inhalant popular among members of the queer community who found it enhanced experiences on the dance floor and in sexual intercourse.24 Physicians thus described a spatial configuration located in downtown Manhattan through which biological substances posed a threat to the health of living organisms. This claim had terrible consequences for the activist spaces and urban fabrics that confronted the epidemic: during the decade to come, most of the saunas and bathhouses that operated in New York were forcibly closed after local health officials tagged them as places of “high-risk sexual activities.”25 The remnants of Pier 45 were demolished. The activist history of these places was “cleared.”26

Sylvia Rivera at the piers in 1996. Courtesy of Valerie Shaff.

There’s so many fucking buildings in this fucking Manhattan

Studies of epidemics tend to focus on the metaphor of the healthy body as being attacked by an external agent. But the interconnection of bodies, other bodies, viruses, bacteria, microbes, architectures, technologies, and environments are intrinsically founded in their contagiousness. Ultimately, heterogenous corporality composes a type of urban form, one that exceeds its understanding as the unfolding of infrastructures, land uses, and buildings. Instead, it becomes a form of collective embodiment that challenges the exceptionality of the human flesh as much as its individuality, to understand it as both infiltrating and being infiltrated by, viruses, buildings, technologies, regulations, and policies.

When Sylvia Rivera shouted to the authorities “stay away from my house!” while being evicted, “house” not only referred to the physical construction of her home. She was confronting teleological progress with the project of a technosocial assemblage based on contagiousness and mutual caring that could push for a queer ecology and defying colonial narratives of race, sex, gender, and nature.27 The territorialization of epidemics, identities, and citizenship not only shape the built environment, but the built environment shapes them in return. Architecture thereby assumed the form of an expanded spatial practice that involves a set of material, bodily, economic, social, cultural, and ecological questions. When Rivera was trying to save her home from demolition, she said, “there’s so many fucking buildings in this fucking Manhattan.”28 What New York City was losing with the demolition of Pier 45 was not just a series of dwellings. It was losing a complex ecosystem of coexistence within a specific environment of mutual dependency that recognized its contagious nature.

Johnson’s death was ruled an accident/suicide, but Marsha’s friends and trans activists, especially Victoria Cruz (from the New York City Anti-Violence Project), fought this version over the years and through an increasing amount of evidence. They said she never wanted to die, and that the previous night witnesses saw her in a state of distress because she was being harassed by men—something common among New York sex workers, especially those like Johnson, an African American gender dissident. Maybe she was murdered, or perhaps she accidentally fell into the freezing waters of the Hudson. Sylvia, who was not living in New York at that time, came back to Manhattan to honor Johnson’s death, maintain her memory, and fight to reopen the case along with others until the authorities agreed to change the cause of death to “undetermined causes.”

Part of the information about Sylvia Rivera’s life in the piers comes from a recorded interview that Randy Wicker did with her in 1992.

Interview with Sylvia Rivera, WPQG News, New York, April 6, 1996.

David Stout, “Eviction Day Along the Curb of a Dead Road,” The New York Times, April 3, 1996.

Ibid.

Here transness should be understood, as Jack Halberstam points out, as the understanding of the body as fragmentary and internally contradictory, remapping gender and its relations to race, place, class, and sexuality. See Jack Halberstam, Wild Things: The Disorder of Desire (Durham: Duke University Press, 2020). See also C. Riley Snorton, Black on Both Sides: A Racial History of Trans Identity (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2017).

City Club of New York, The Wastelands of New York City: A Preliminary Inquiry into the Nature of Commercial Slum Areas, Their Potential for Housing and Business Redevelopment (New York: City Club of New York, 1962).

Proposals like Fuller and Shoji Sadao’s Manhattan Dome (1964) went even further, cutting Lower Manhattan off from the rest of the island, encapsulating the rest of it under a dome; Kevin Roche proposed the encapsulation of an autonomous atmosphere in the Ford Foundation building (1967).

Wendell E. Pritchett, “The ‘Public Menace’ of Blight: Urban Renewal and the Private Uses of Eminent Domain,” Yale Law and Policy Review 21, no. 1 (2003): 1199.

This was the term that Lewis Mumford used in an article published in 1962. Lewis Mumford, “The Skyline: Mother Jacobs’ Home-Remedies,” New Yorker, December 1, 1962.

Aaron Shkuda, The Lofts of SoHo. Gentrification, Art, and Industry in New York, 1950–1980 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2016), 15.

Lola Hinojosa, “Gordon Matta-Clark’s Day’s End (1975),” Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofia, 2007, ➝.

Grace Dunham, “Out of Obscurity: Trans Resistance 1969–2016,” in Trap Door: Trans Cultural Production and the Politics of Visibility, eds. Reina Gossett, Eric A. Stanley and Johanna Burton (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2017), 91.

Popular narratives said that Johnson was the one who ignited the riots by throwing a brick at the police. As a reminder, Marsha carried a cardboard brick every gay pride (an actual brick was too heavy to carry during the celebrations).

Lisa Duggan, “The New Homonormativity: The Sexual Politics of Neo-Liberalism,” in Materializing Democracy, eds. Russ Castronovo and Dana D. Nelson (Durham: Duke University Press, 2002). See also Martin F. Manalansan IV, “Race, Violence, and Neoliberal Spatial Politics in the Global City,” Social Text 23, nos. 3–4, (2005): 84–85.

Martin Duberman, Stonewall: The Definitive Story of the LGBTQ Rights Uprising that Changed America (New York: Penguin Random House, 2019), 309–310.

“Current Trends Prevention of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome (AIDS): Report of Inter-Agency Recommendations,” Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 32, no. 9 (1983): 101–3.

The idea of a chosen kin is based in part on Donna Haraway’s notion of “staying with the trouble” of living with and in relation to nonhuman others (in this case, HIV and AIDS), which are kin in the sense of “something other, and more than entities tied by ancestry or genealogy.” See Donna Haraway, Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene (Durham: Duke University Press, 2016).

For more on HIV/AIDS kin and its architecture, see Ivan L. Munuera, “HIV and AIDS Kin: The Discotecture of the Paradise Garage,” Thresholds 48 (Spring 2020): 133–147.

On May 31, 1987, President Reagan finally declared AIDS a public health emergency, giving his first major address on AIDS. It was at an outdoor speech in Washington organized by amfAR, the American Foundation for AIDS Research.

Steven Epstein, Impure Science: AIDS, Activism, and the Politics of Knowledge (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1996), 55.

This idea continued even into the late 1990s with authors like Gabriel Rotello, who blamed urban, gay, sexual culture for causing AIDS and the continued spread of HIV infection. See Gabriel Rotello, Sexual Ecology: AIDS and the Destiny of Gay Men (New York: Dutton, 1997).

See Michael Bronski, “AIDing Our Guilt and Fear,” Gay Community News, October 9, 1982.

David France, How to Survive a Plague (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2016), 37.

Maurice Carroll, “State Permits Closing of Bathhouses to Cut AIDS,” The New York Times, October 26, 1985.

In order to recover this and other histories, it is essential to highlight the work of the NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project, active since 2015, and the efforts of their founders and directors, Andrew Dolkart, Ken Lustbader, and Jay Shockley.

Andil Gosine, “Non-White Reproduction and Same Sex Eroticism: Queer Acts Against Nature,” in Queer Ecologies: Sex, Nature, Politics, Desire, eds. Catriona Mortimer-Sandilands and Bruce Erickson (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2010), 149–150.

Interview with Sylvia Rivera, WPQG News.

Sick Architecture is a collaboration between Beatriz Colomina, e-flux Architecture, CIVA Brussels, and the Princeton University Ph.D. Program in the History and Theory of Architecture, with the support of the Rapid Response David A. Gardner ’69 Magic Grant from the Humanities Council and the Program in Media and Modernity at Princeton University.