Sick Architecture is a collaboration between Beatriz Colomina, e-flux Architecture, and the Princeton University Ph.D. Program in the History and Theory of Architecture, with the support of the Rapid Response David A. Gardner ’69 Magic Grant from the Humanities Council and the Program in Media and Modernity at Princeton University, featuring contributions by Tairan An, Guillermo Sanchez Arsuaga, Victoria Bergbauer, Carrie Bly, Beatriz Colomina, Rebecca Kellawan, Iván López Munuera, Kara Plaxa, Elizabeth A. Povinelli, Paul B. Preciado, Gizem Sivri, Shivani Shedde, and Mark Wigley. The project began as a Ph.D. seminar in the fall of 2019 and will continue in 2021 as an exhibition at CIVA in Brussels.

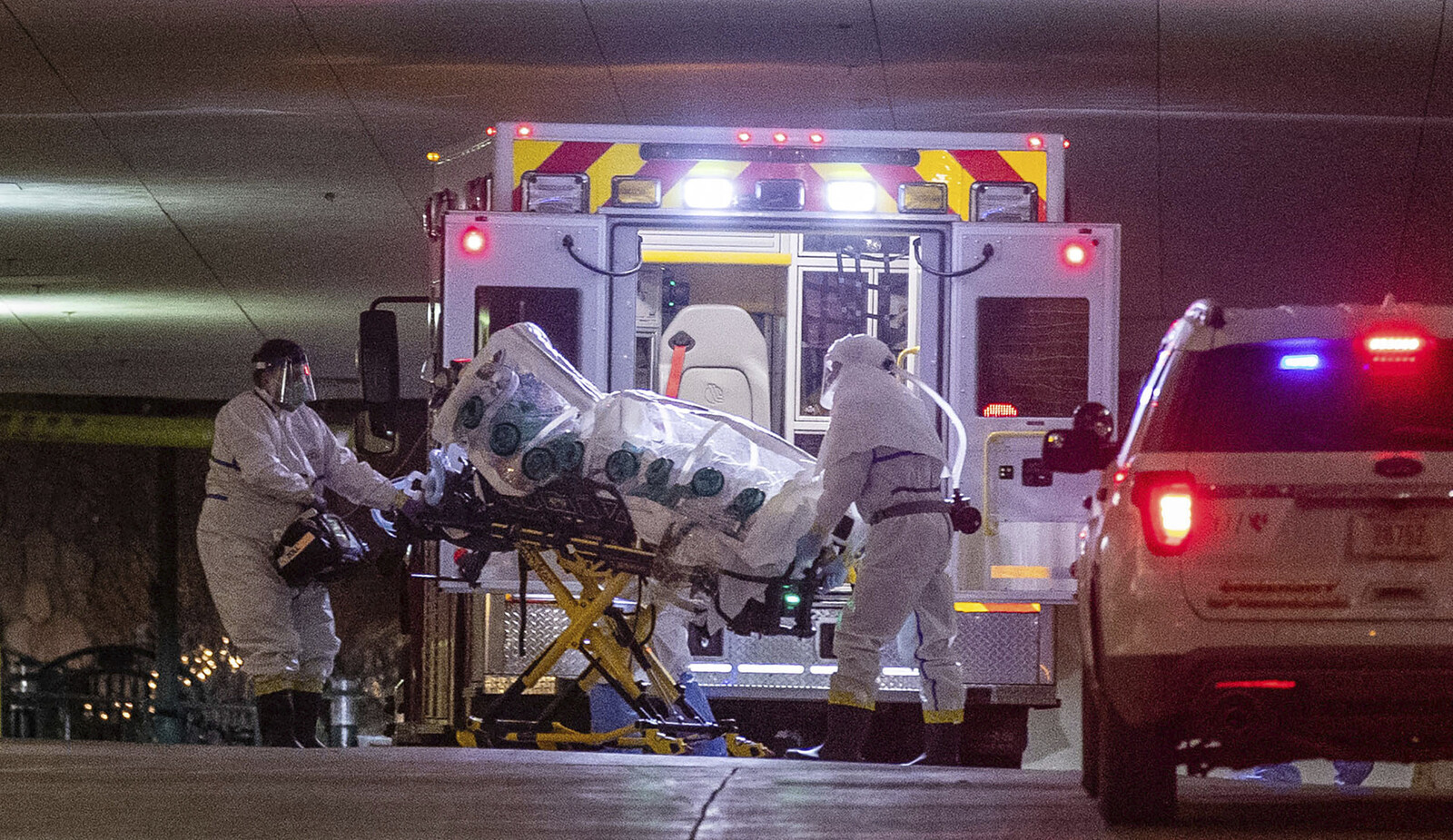

A grid of empty white beds in a dark cavernous space—waiting for bodies. One architecture inside another. A field hospital is set up within days to accommodate 5,500 patients in two convention center halls in Madrid. Buildings designed for temporary events now host an emergency medical architecture, a space for disease.

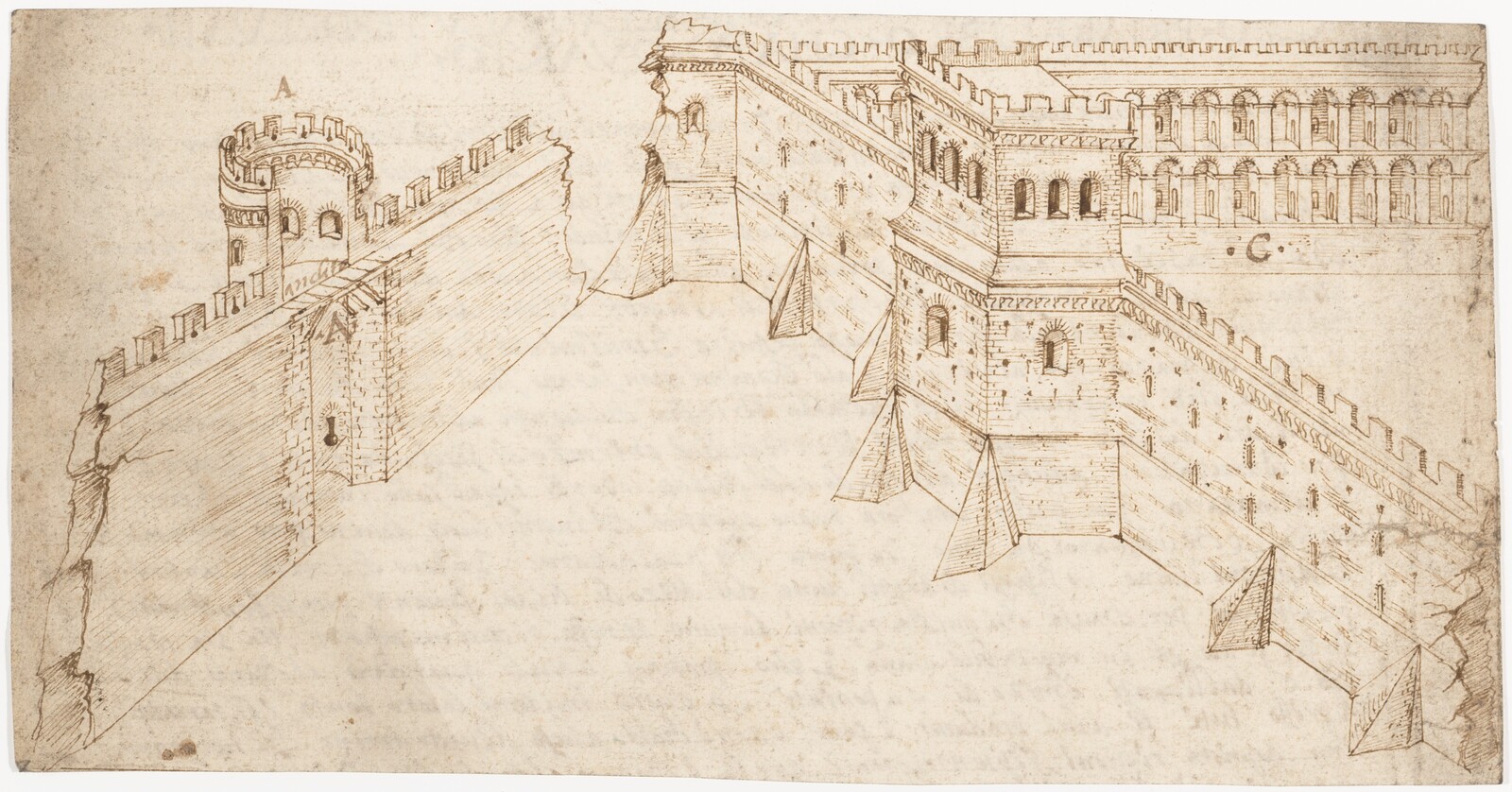

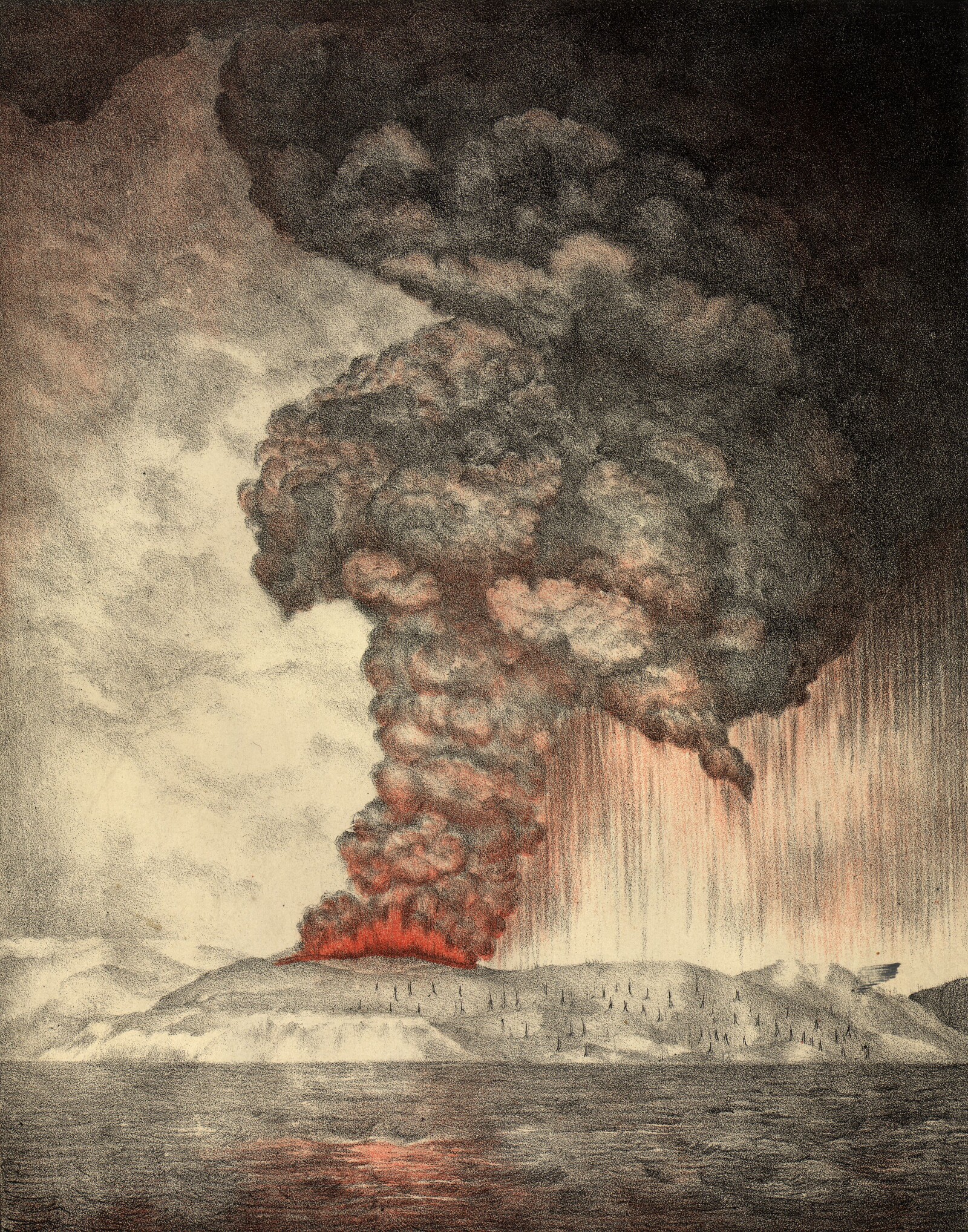

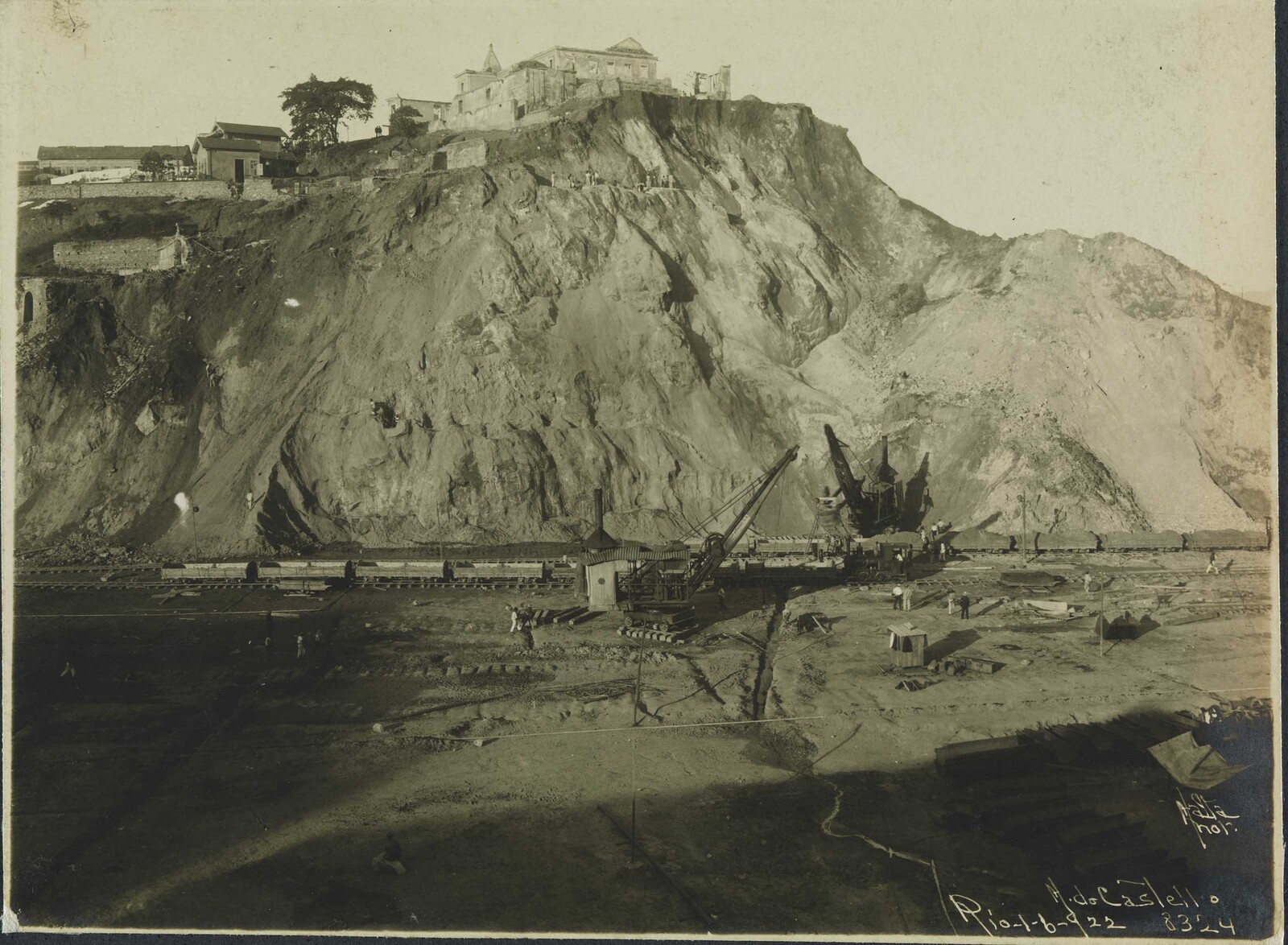

Sick Architecture is not simply the architecture of medical emergency. On the contrary, it is the architecture of normality—the way that past health crises are inscribed into the everyday, with each architecture not just carrying the traces of prior diseases, but having been completely shaped by them. Every new disease is hosted within the architecture formed by previous diseases in a kind of archeological nesting of disease. Each medical event activates deep histories of architecture and illness, along with all the associated fears, misunderstandings, prejudices, inequities, and innovations.

All architecture is sick. Illnesses and architecture are inseparable. It could even be argued that the beginning of architecture is the beginning of disease. As doctor Benjamin Ward Richardson put it when introducing Our Homes and How to Make them Healthy, a compendium of texts by doctors and architects for the 1884 International Health Exhibition in London: “Man, in constructing protection from exposure has constructed the conditions for disease.”

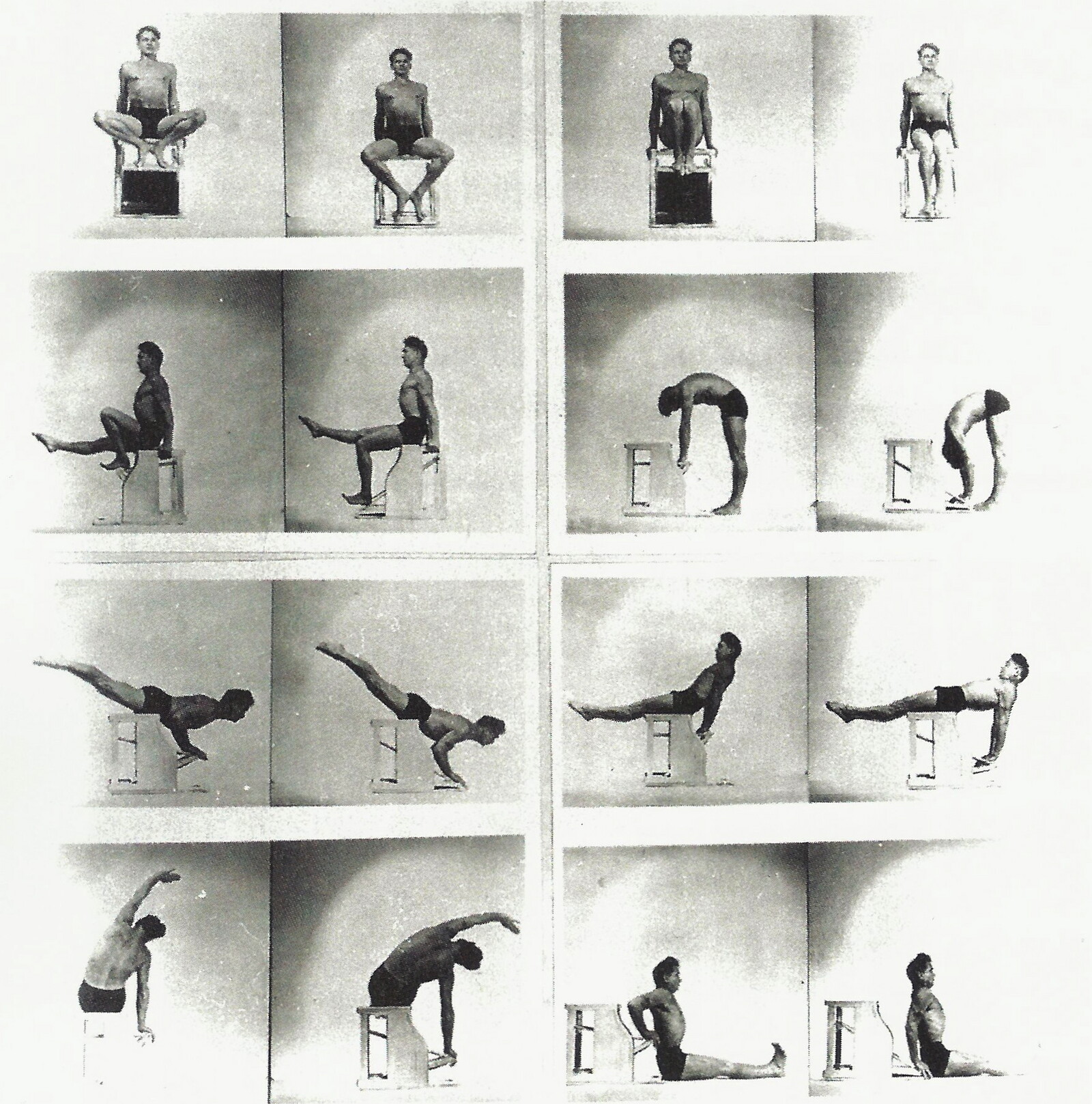

There is no disease without architecture, and no architecture without disease. Doctors and architects have always been in a kind of dance, often exchanging roles, collaborating, influencing each other, even if not always synchronized. Furniture, rooms, buildings, cities, and networks are produced by medical emergencies that encrust themselves one on top of another over the centuries. We tend to forget very quickly what produce these layers. We act as if each pandemic is the first, as if trying to bury the pain and uncertainty of the past.

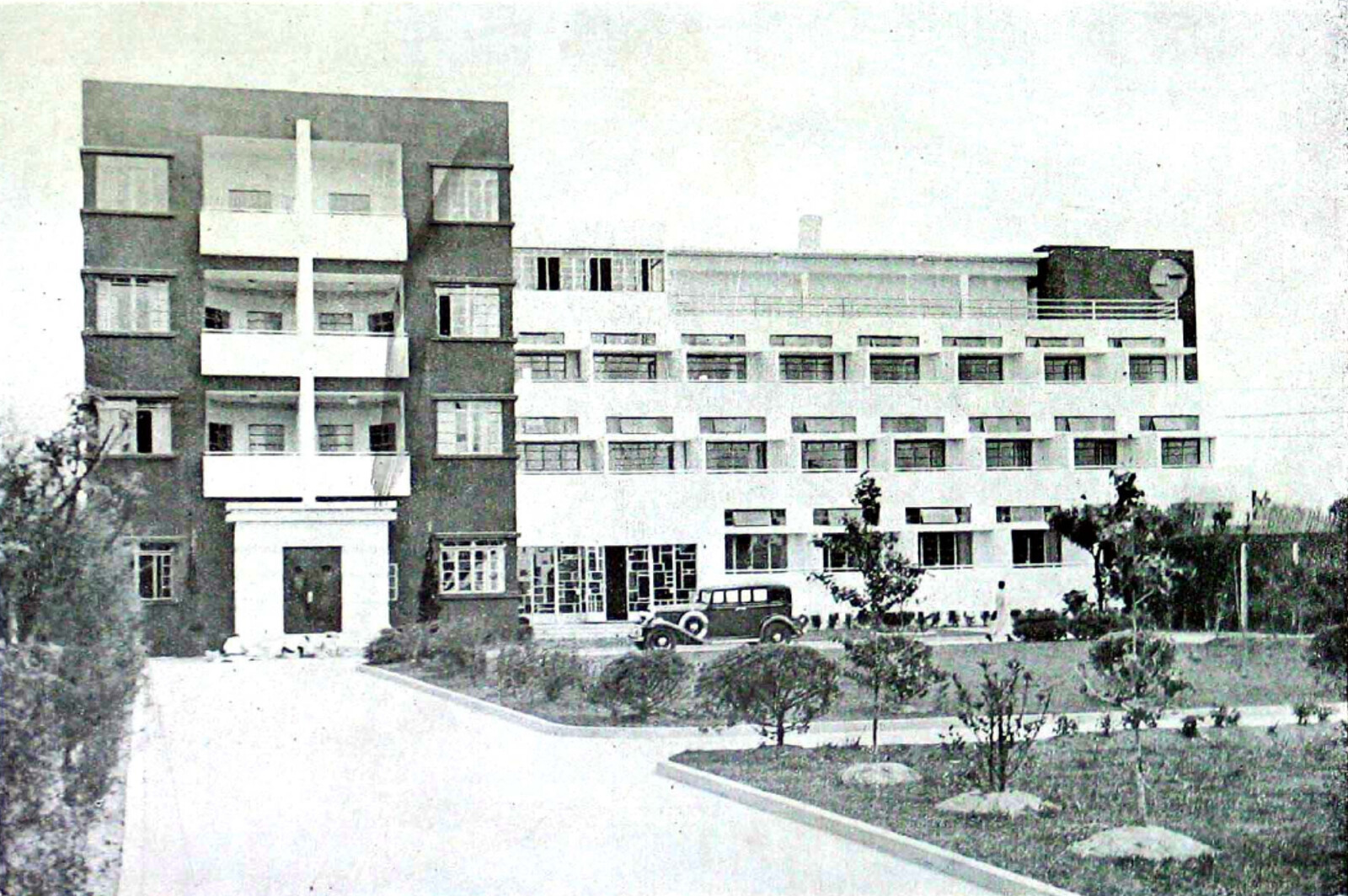

Modern architecture was produced under emergency conditions. Throughout the nineteenth century and the first half of the twentieth, millions died of tuberculosis every year all over the world. Modern buildings offered a prophylactic defense against this invisible microorganism. All the defining features of modern architecture—white walls, terraces, big windows, detachment from the ground—were presented as both prevention and cure. Yet the medicinal nature of modern architecture and the unimaginable horror it was responding to has been largely forgotten. The image of white buildings whites out the trauma that gave birth to them.

Sick Architecture tries to reverse this forgetting. It does not seek to rationalize the current pandemic or speculate about its impact directly. Instead, it offers a wider, historical, and more complex discourse with which we may think about the present. It explores different dimensions of the relationships between concepts of illness, space, institutions, territories, technologies, politics, biologies, and philosophies. “Architecture,” here, means not just buildings, cities, and spaces, but structures of thinking, protocols, and logics. And “sick” means not just recognizable diseases but things not yet recognized or treated as disease. Both sickness and architecture need to be expanded and destabilized. To think the intimate relationship between them is to think both differently.

Sick Architecture is a collaboration between Beatriz Colomina, e-flux Architecture, CIVA Brussels, and the Princeton University Ph.D. Program in the History and Theory of Architecture, with the support of the Rapid Response David A. Gardner ’69 Magic Grant from the Humanities Council and the Program in Media and Modernity at Princeton University.