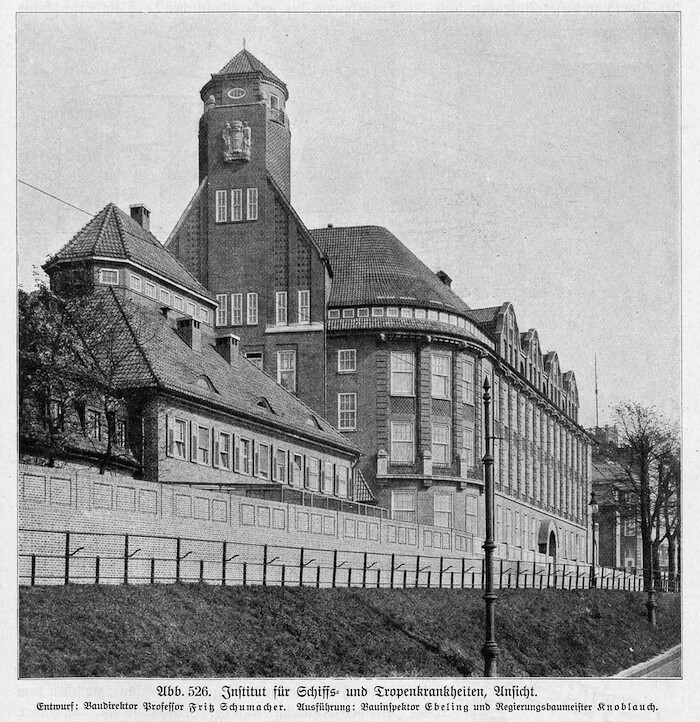

On May 28, 1914, the Institut für Schiffs- und Tropenkrankheiten (Institute for Maritime and Tropical Diseases, ISTK) in Hamburg began operations in a complex of new brick buildings on the bank of the Elb.1 The buildings were designed by Fritz Schumacher, who had become the Head of Hamburg’s building department (Leiter des Hochbauamtes) in 1909 after a “flood of architectural projects” accumulated following the industrialization of the harbor in the 1880s and the “new housing and working conditions” that followed.2 The ISTK was one of these projects, connected to the port by its fourfold mission: to research and heal tropical illnesses; to teach doctors, nurses, and travelers about them; to support the Hamburg Port Medical Service; and to support endeavors of the German Empire overseas.

First established in 1900 by Bernhard Nocht, chief of the Port Medical Service, the ISTK originally operated out of an existing building, but by 1909, when the Hamburg Colonial Institute became its parent organization (and Schumacher was hired by the Hamburg Senate), the operations of the ISTK had outgrown the existing, partially modified, facility. The need for a new building and its commission by the city was an opportunity for Schumacher to show how he could contribute to guiding the city’s economic and architectural growth in tandem, and for Nocht, an opportunity to establish an unprecedented spatial paradigm for the field of Tropical Medicine that anchored the new frontier of science in the German Empire.

Despite this shared drive to contribute to the health and wealth of Hamburg within the context of its expanding global network, in the same year that the new ISTK opened, two different sets of images and texts describing the facilities were published that revealed a distance between conceptions of the building. One, a three-page entry in the compendium Hamburg und seine Bauten, was authored by Schumacher, intended to circulate in the fields of architecture, engineering, and city planning.3 The other, an eighteen-page journal article called “Das Neue Institut für Schiffs- und Tropenkrankheiten,” was written by Nocht, speaking directly to scientists and researchers in the field of Tropical Medicine.4

The difference between the representations of the ISTK building in the two publications show that neither presents a complete portrait of the discourse that surrounded the intent and production of the building between its commission in 1910 and its completion in 1914. While this divergence is understandable, given that each discipline—architectural and scientific—operates within its own narratives, the distance between the narratives is not insignificant. In the ISTK, architecture and medicine were participating in a shared, though silent, discursive operation that was greater than either one in isolation.

Schumacher’s ISTK

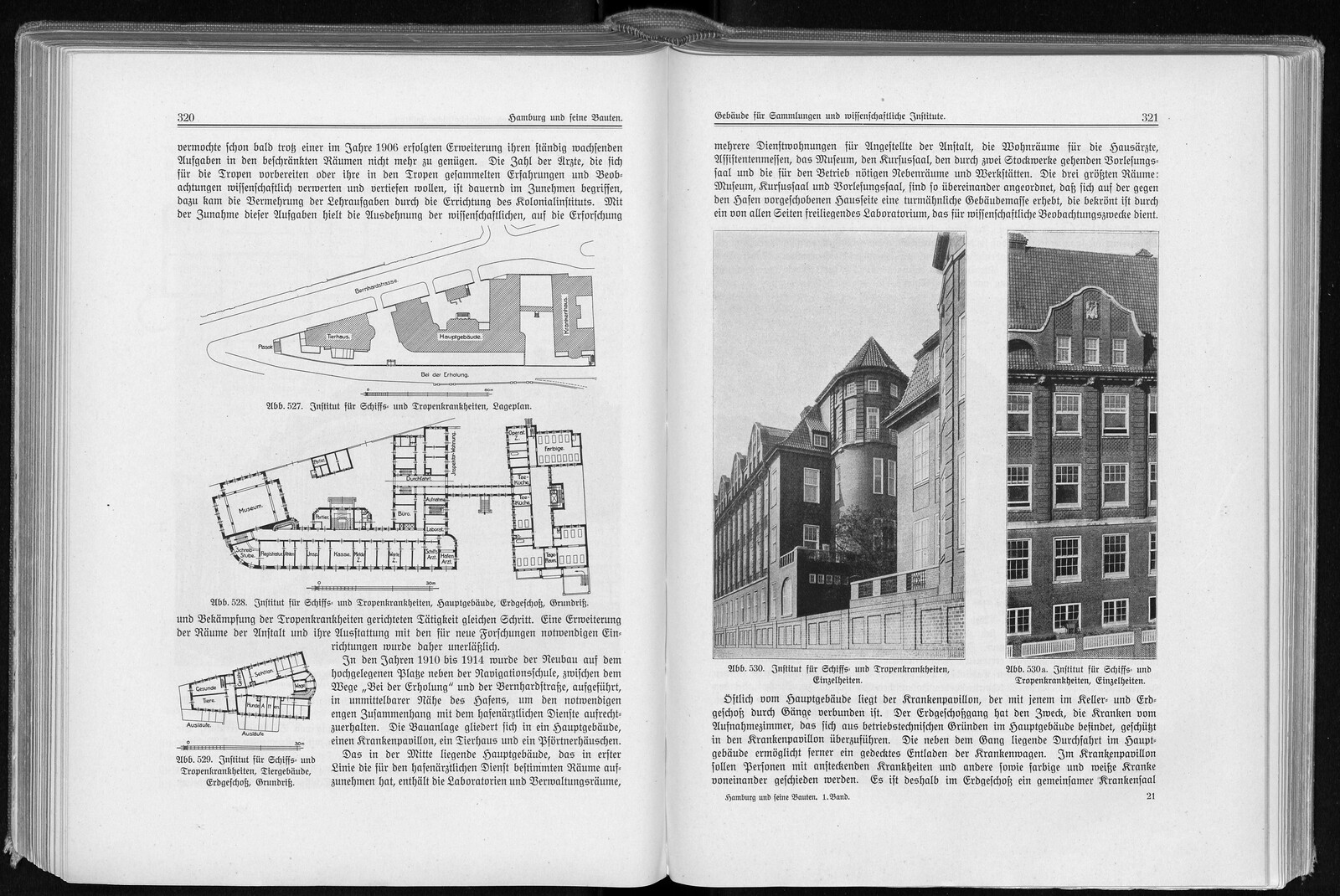

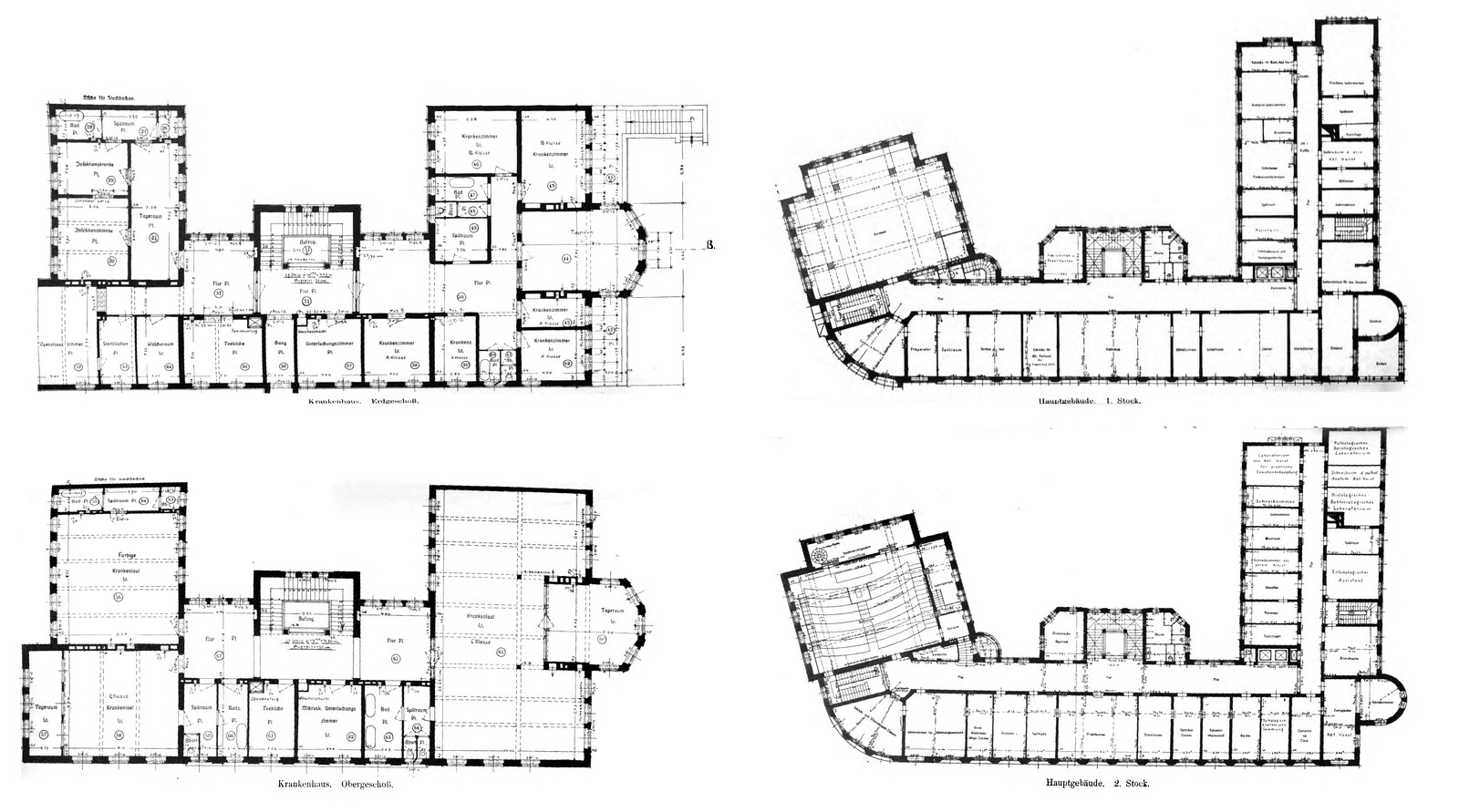

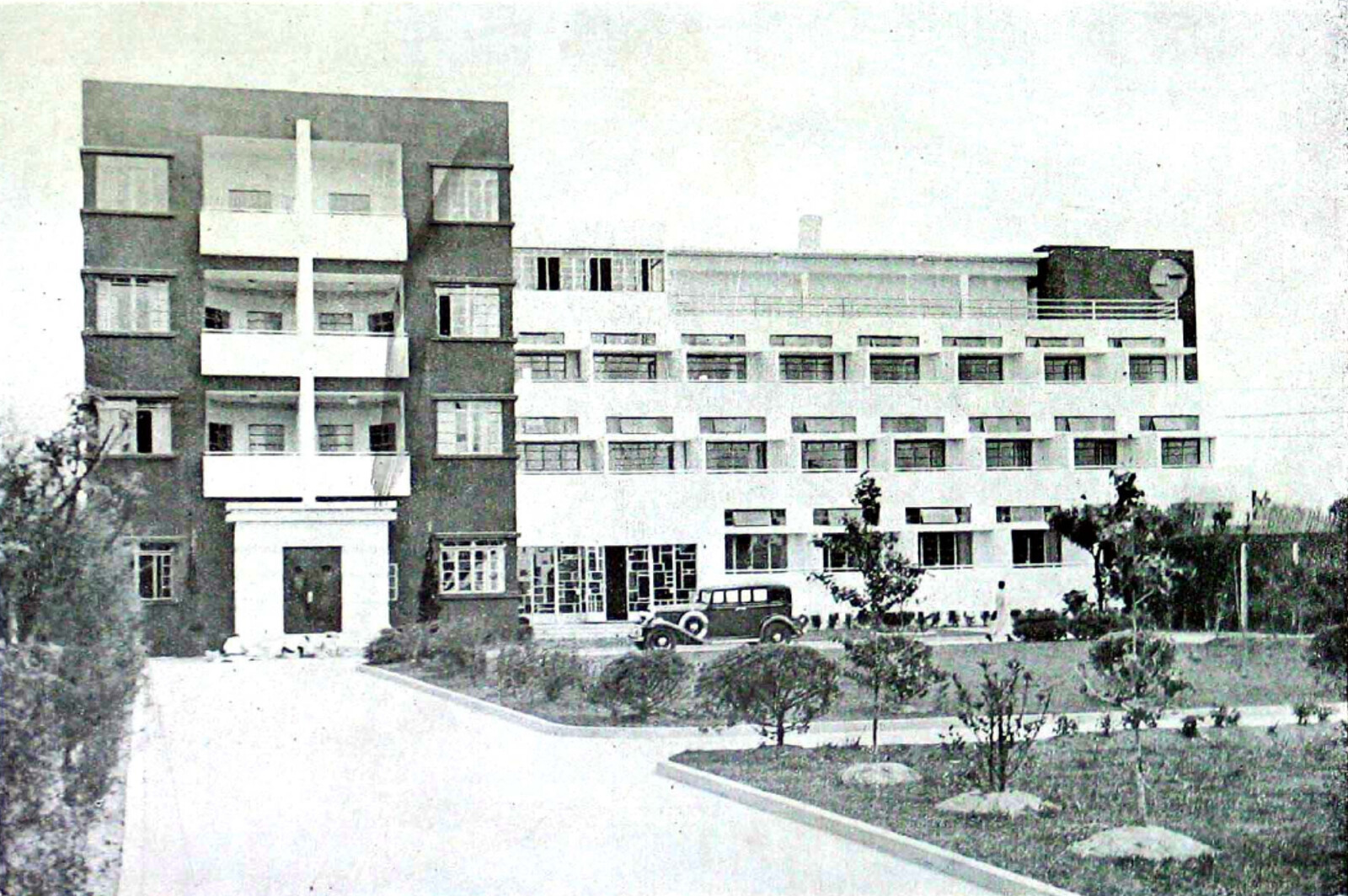

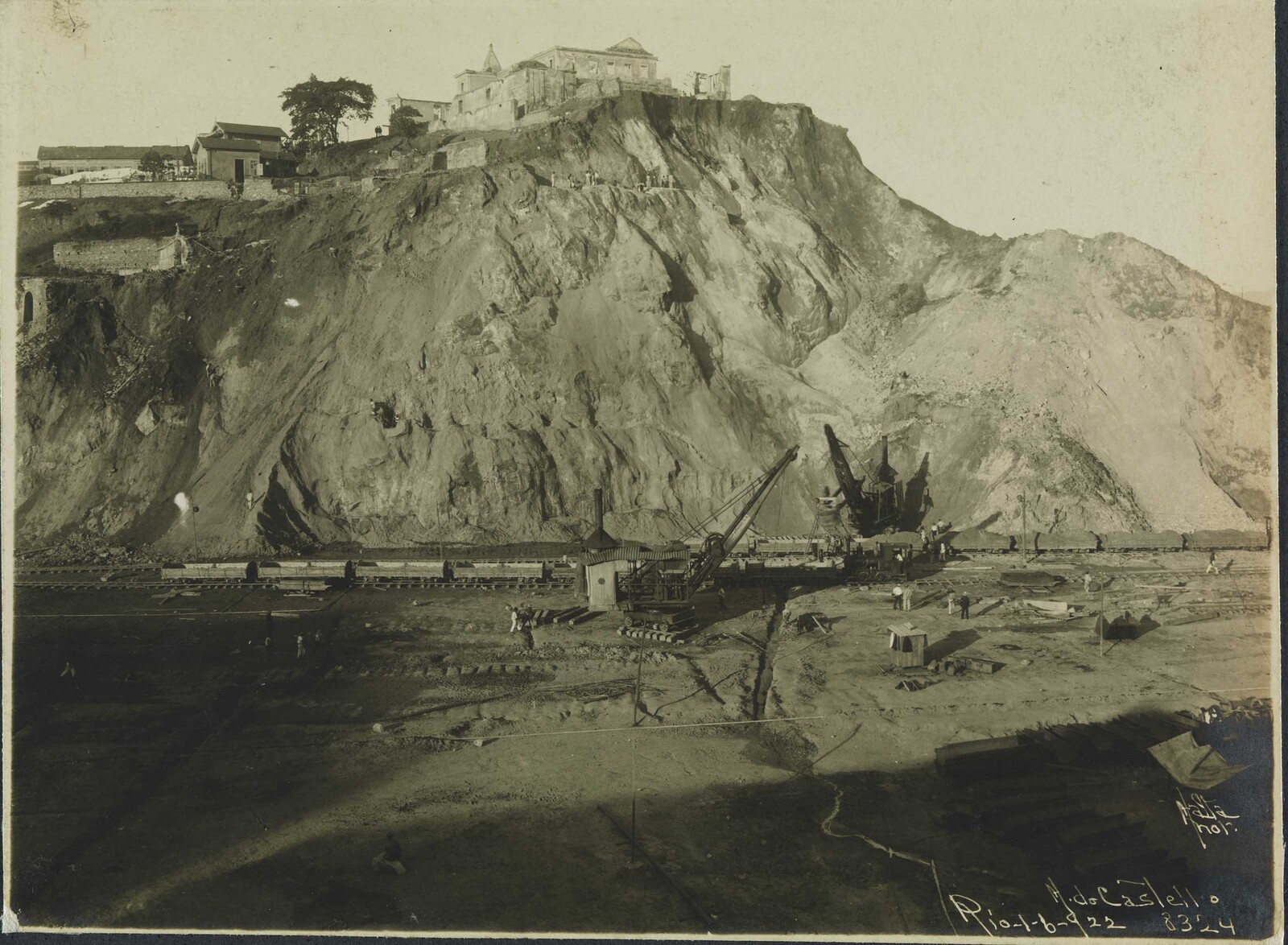

Schumacher’s entry for the ISTK in Hamburg und seine Bauten consists of a site plan, a set of ground level floor plans, a short text, and three black and white photographs. The site plan shows a composition of three primary buildings: an animal house, a main building, and a hospital, spread across a triangular site, limited by the acute vector of two roads (Bernardstraße and Bei der Erholung) meeting at a public urinal (pissoir)—a civic reminder that even piss had its place in city health policies. A brick wall surrounds the site, making the institution appear as an island disconnected from even the port which gave it purpose.

The three diagrammatic plans convey little detail as to materiality or experience of the building interiors, but do however begin to map the pathways of circulation for people, light, air, germs, animals, and information. They show concisely an architectural parti which organizes rooms within each building along one or two sides of a corridor spine. Nearly every room and corridor shown on these plans has at least one window, allowing sunlight and air to permeate most parts of the building. A gatehouse at the entry to the main building courtyard controlled the flow of pedestrians and vehicles. A healthy human visitor could pass through the main entry to the main building, and proceed either to their workspace or to the museum. A sick human visitor would be taken by ambulance to the main building, and then be assessed and itemized by the live-in inspector. The sick patient would be transferred to the hospital via a covered corridor, while the intake form recording their identity and relevant medical information would be held in the main building. Like the hospital, the animal house was also separated from the main building, increasing access to “fresh” exterior air and decreasing the chance of cross-contamination between sick occupants and scientists.

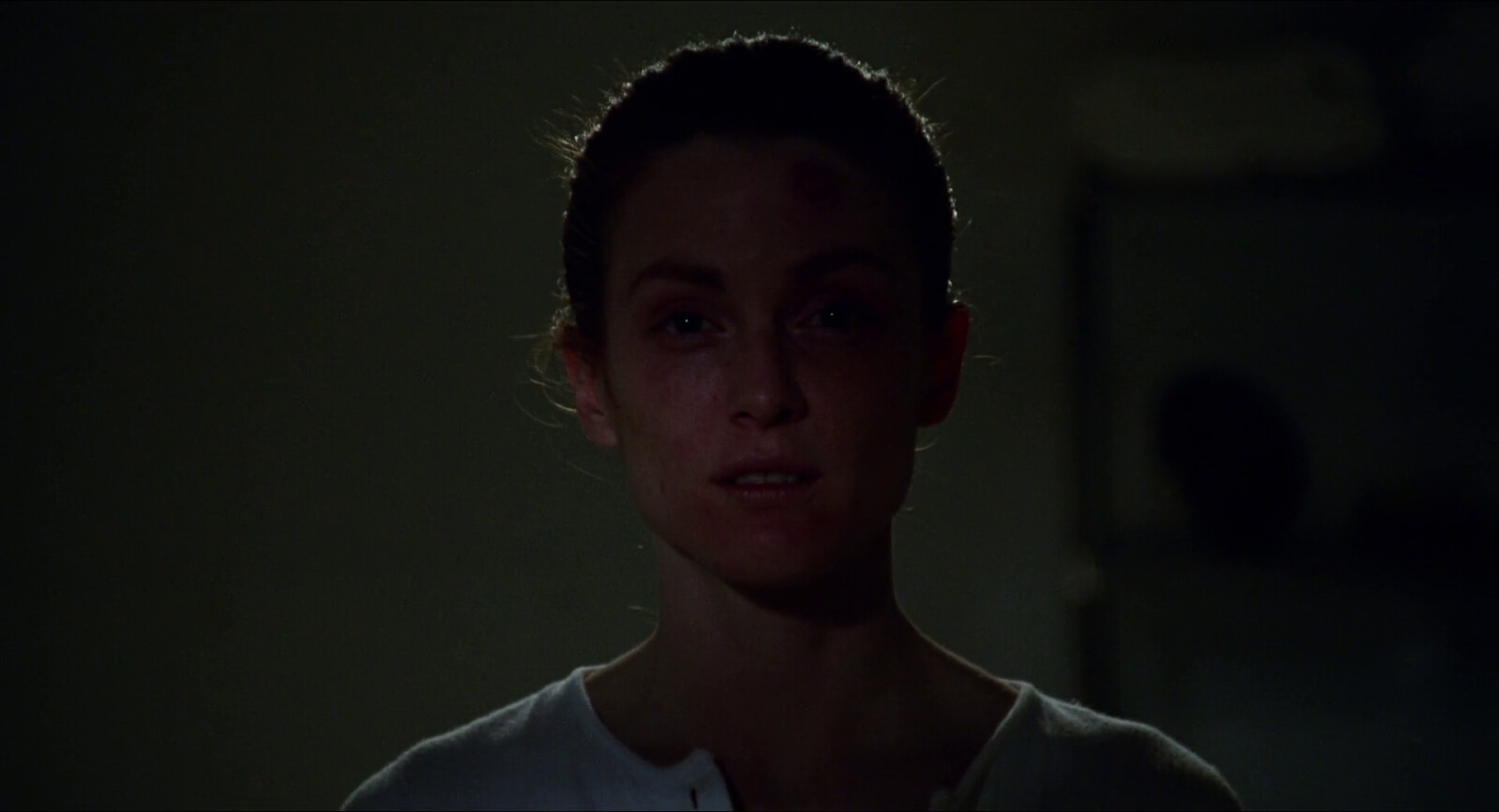

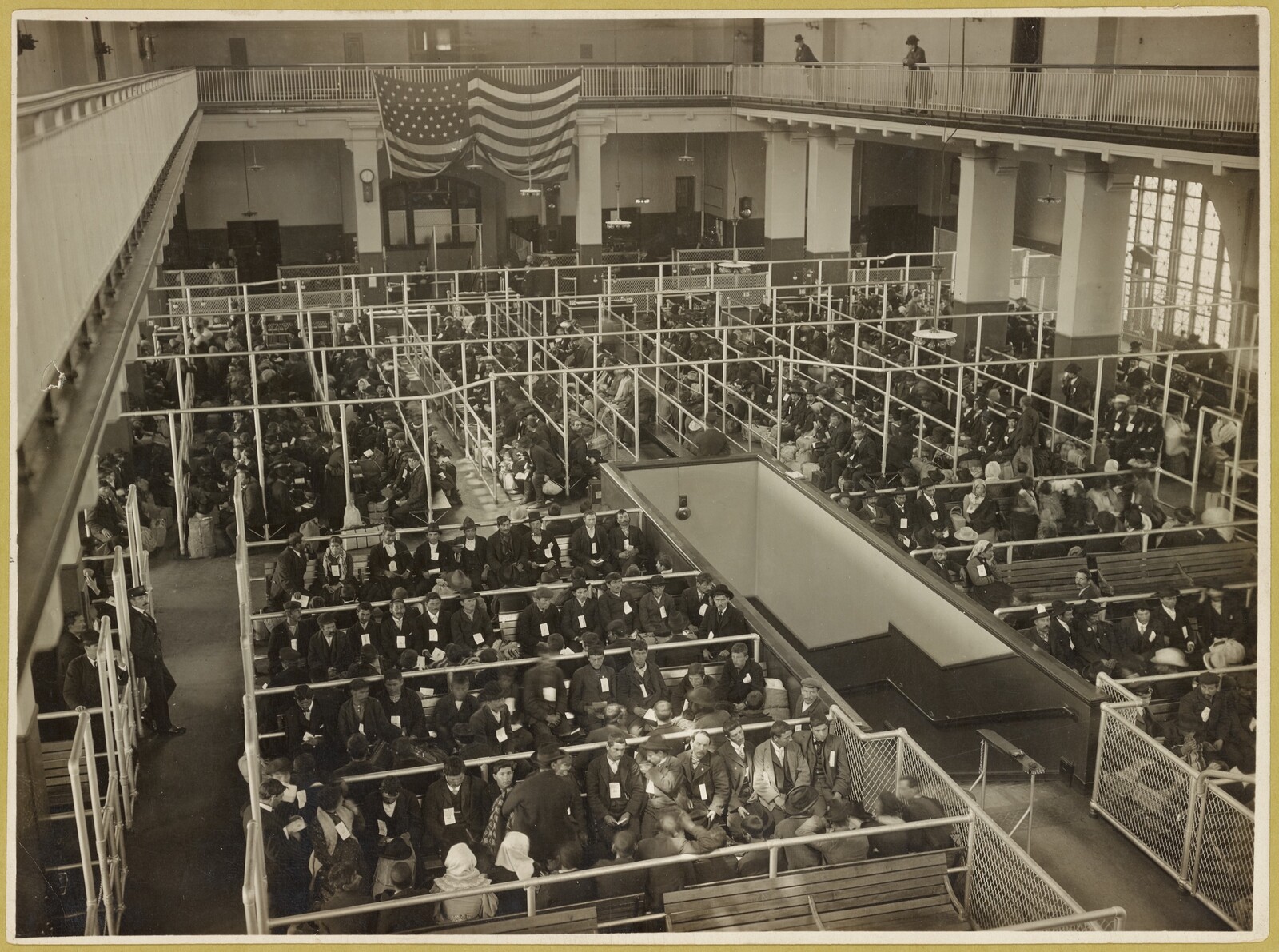

Photo of the ISTK from Fritz Schumacher’s article in Hamburg und seine Bauten, ed. Merckel (Hamburg: Bonsen und Maasch, 1914).

Like the site plan, the three photographs reveal very little about the context of the buildings. In fact, the entry focuses almost exclusively on the brick walls, and their division between interior and exterior. The photographs are all taken from outside the brick wall surrounding the site, presenting the ISTK as a passerby would see it from the street. The even grey walls of all the buildings are punctured, regularly and repeatedly, with white trimmed windows. Their tiled roofs are tall and steeply pitched, augmented by chimney and vent stacks. A tower protrudes from the middle building, breaking the repetition of the windows and elevating a stone emblem above the roofline. Special attention has been given to the way these façades are presented to the reader. The buildings have either been photographed from an extreme angle—reducing the foreground as much as possible in order to maximize the presence of the building in the frame—or cropped to show only a portion of a building façade—revealing in greater detail patterns in the brick coursing.

The brick used on the ISTK façades was key to Schumacher’s larger Städtebau plan for Hamburg, which envisioned the city as a vehicle for a “harmonious” synthesis between aesthetics and economy.5 “L’art pour l’art, das ist die Verneinung aller gesunden Architektur [Art for art’s sake, that is the negation of all healthy architecture],” he wrote in 1916, urging other architects to look beyond the pretty images produced for exhibitions, and instead consider how their projects contributed to and participated in the artistic, economic, social, and historical dimensions of a city—each of which he claimed needed to be balanced against one another to create a “healthy” city.6 For Schumacher, brick was a material in which each of these dimensions could be found and finessed for Hamburg. Used by early nineteenth-century Hamburg architects, who acquired their penchant for neo-gothic brickwork at the Hanover School, brick had both a historical presence and an aesthetic pedigree in Hamburg, which contributed to its social propriety. Yet brick also held potential to be modernized, and by improving its quality and production techniques, north German brick could become an economic asset. In 1920, Schumacher reflects:

A look at the aesthetics of [brick] reveals not an artistic view, but an artisan spirit, and an artisan spirit is what architecture needs in our time if it is to be healthy for a fresh life; it is the natural ground of all sensible and fruitful further development.7

In brick, Schumacher found a confluence of art and industry that exemplified his ideal of a harmonized and healthy city. Indeed, Schumacher did not use local bricks as he found them; he sorted them, establishing a system of desired properties, and reshaped the Hamburg brick industry to conform to his needs or, as he perhaps saw it, the needs of the city.8 In 1900 Schumacher noted there were few German manufacturers of appropriately sized, glazed, textured, and colored bricks, but by 1919, his colleagues were amazed at the selection and growth of the industry.9 According to Hermann Muthesius, a prominent advocate for the Arts and Crafts movement in Germany and intellectual leader in the Deutscher Werkbund,

Schumacher prompted the German brick and tile industry and found it ready to follow his suggestions, so that today we can obtain every type of brick that is refined in terms of tone and color. In particular, it is dark, brownish, violet, semi- and completely sintered varieties that Schumacher prefers. They are used uniformly, graded, or mixed. In this way, the surface can be given life, a tingling, iridescent appeal can be achieved, and a clear structure of the exterior can be created. The mastery of Schumacher expresses itself precisely in this extremely carefully considered effect of the surface, which has achieved the finest quality here. In doing so, he has brought a new side to the art of brick construction and has acted as a model.10

As if unaware of his own role in the production, in 1920 Schumacher himself commented: “The brick building has recently found a constantly growing community, especially in northern Germany. There are many reasons for this, but among them the most clear and audible reason for feeling emerges among them: one sees in it a sign of ‘down-to-earth’ sentiment and welcomes its blooming in the name of the goals of ‘local art’ [Heimatkunst].”11 The right, healthy brick façade produced both sentimental (aesthetic) and practical (economic) results.

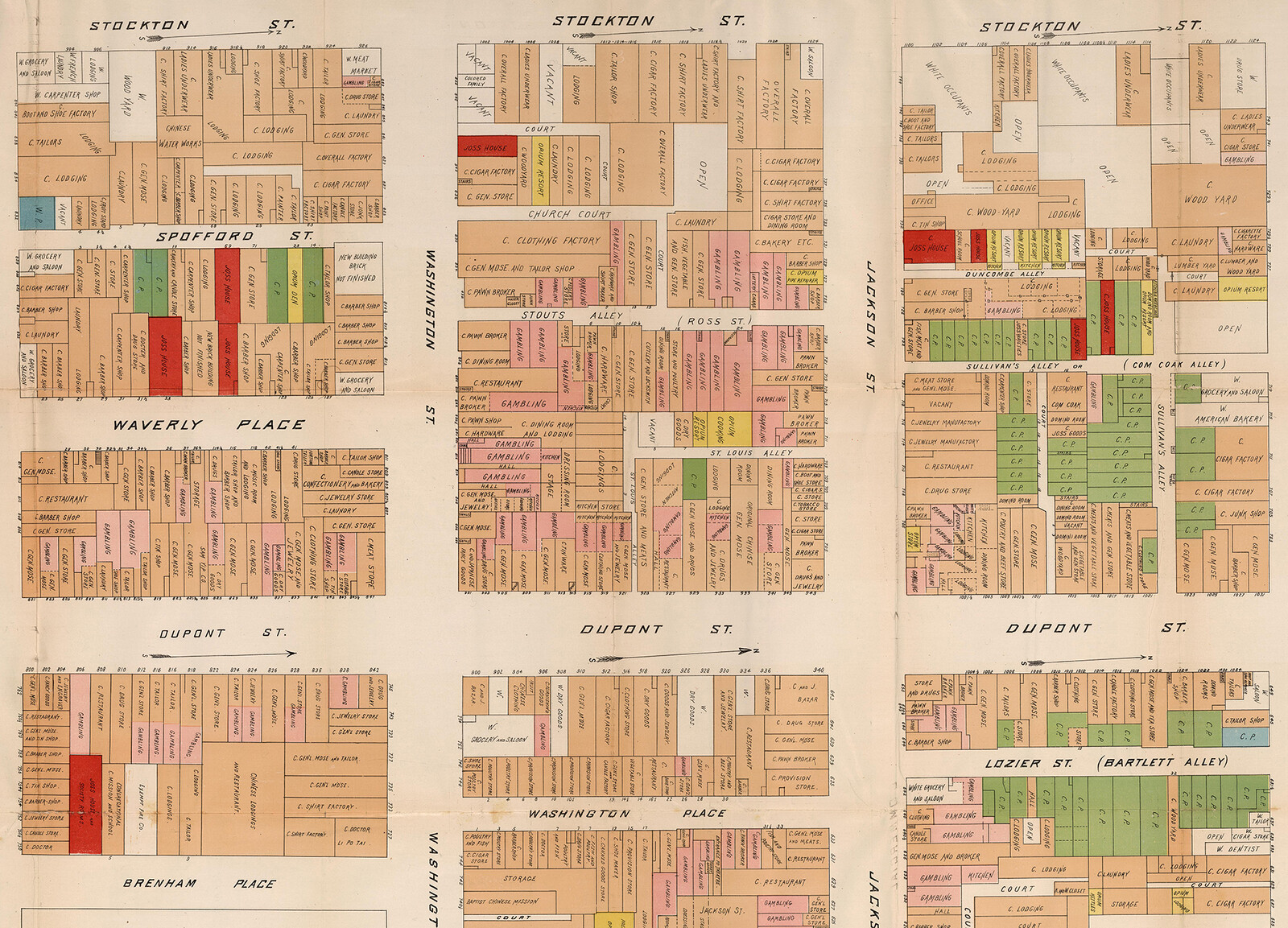

It is perhaps indicative of Schumacher’s distinctly non-medical and rather market-oriented definition of health that he chose brick to carry forward his vision of a healthy city, even though this material had already been used in Die Speicherstadt, a warehouse district in Hamburg where unequal social conditions had only grown more exacerbated under Schumacher’s supervision as head of the city’s building department. Die Speicherstadt was constructed in three phases in 1883–1889, 1891–1897, and 1899–1927, led by Hamburg Chief Engineer Franz Andreas Meyer.12 By serving the port, the warehouses facilitated the expansion and security of Hamburg’s wealth. Rendered in red brick—used both practically as a fire barrier and in dialogue with the historical local aesthetic of neo-Gothic brickwork—they contributed to the aesthetic identity of the city as envisioned by Schumacher. Yet the collective profits accrued to the city by these buildings, as investments in Hamburg’s financial and aesthetic infrastructure, did not increase economic prosperity and social equity for all.

Before the first construction phase began in 1883, a residential area for harbor workers was demolished to make way for the warehouses. After the contract for the port expansion was negotiated in 1881, over 20,000 people were pushed out of their homes and into adjacent areas of the city, which soon became overcrowded and more expensive as demand for housing grew.13 In turn, these overcrowded areas of the city, with housing that was poorly ventilated and likely contained shared bathrooms, were the worst hit by the Hamburg cholera epidemic of 1892, the most devastating in Europe that year.14

The 1892 cholera epidemic, the last of the nineteenth century, articulated the growing inability of the Hamburg Senate, comprising the city’s elite, to manage class relationships. In the late nineteenth century, a city that was explicitly run by and for the merchant class was vastly out of touch with the rest of Germany and Europe, which had by then formed strategies for internal politics that framed hygiene and the working class as integral, rather than disposable, to industrialization and nation building. The epidemic had revealed a rupture in the social politics of the city, affirming that health was not only an internal condition belonging to individual bodies, but rather extended into the overt and covert operations of the social, political, and physical environment.

In Hamburg, the response to such an ugly disease of the masses was the enforcement of quarantine methods that pushed the working class into the suburbs, isolated immigrants on an island, and separated the sick according to racial identity. In partnership with the German Empire, Hamburg established new hygiene institutions in the city, including the Port Medical Service (a progenitor of the ISTK). When Schumacher became director of the building department in 1909, he furthered this agenda by re-planning dense parts of the city and creating new standards for hygiene in housing. It is uncertain whether Schumacher acknowledged that aesthetic insights could not temper all of the negative effects of economically driven decisions. For Schumacher, in any event, the discourse of the ISTK centered around city building and nation building, brick by brick, mark by mark.

Nocht’s ISTK

Just as the exterior condition of the building was, for Schumacher, part of a much larger plan for the city, the program of the building and its interior were part of the German Empire and Tropical Medicine’s much larger interest in controlling the health and wealth of its nation and colonies. Compared to the entry in Hamburg und seine Bauten, Nocht is more detailed in describing the building’s location and its interior. Each building is documented with two plans, one of the main floor and one upper floor. The text further elaborates the materiality and organization of the interior. Even the site plan has been further elaborated to show pathways and plantings on the site. In addition, four photographs are provided, each remarkably different from those presented by Schumacher. Three photographs depict the building in high contrast sunlight, so that the texture of the façades, carefully detailed in Hamburg und seine Bauten, are rendered flat and often dark. Nocht’s images, however, provide more site context: the ISTK can be seen perched on a steep bank at the edge of the Elb, next to the Hamburg Navigation School, with street cars, horse-drawn wagons, and pedestrians passing by. The fourth photograph, on the other hand, offers a view of the port, countless smokestacks and masts protruding from the horizon. The image appears to be taken from the hillside where the ISTK stands, as though recreating the view from inside the building. In this sense it is the only “interior” image provided in either of the two publications.

Like Schumacher, Nocht’s images of the ISTK again present the buildings as part of a larger project for the city, yet unlike Schumacher’s brick reverie, Nocht’s images draw attention to the project’s routes of circulation, physical proximity, and connection to the port. Indeed, space was made to accommodate for the expanding Hamburg Port Medical Service in the 1914 ISTK building, and its location was coordinated with the construction of the Elbtunnel, completed in 1911, to more easily connect the port and the mainland.

The ISTK was preceded in Hamburg by several hygiene institutions, including the Port Medical Service (run by Nocht), which had been in operation since the cholera epidemic of 1892. Yet the establishment of the ISTK marked a critical shift in medical thinking: it aimed to not only manage illnesses related to the port, but also investigate epidemiological dimensions of these illnesses through teaching, research, and treatment.15 And while the ISTK was not the only institution in Europe to form around the conception and perceived threat of tropical diseases, it was the first to build a facility specifically to support their “exploration and combat” in lockstep, as Nocht described it.16

The field of Tropical Medicine had been established in Germany by the very same journal Nocht published his overview of the ISTK. The Archiv für Schiffs- und Tropen-Hygiene unter besonderer Berücksichtigung der Pathologie und Therapie was first published in 1897, the same year that the German Empire claimed Kiaochow (northeast China) and about two years after it claimed Southwest Africa (Namibia), Cameroon, Togo, East Africa (Tanzania, Burundi, Rwanda), New Guinea (today the northern part of Papua New Guinea), and the Marshall Islands; two years later, it would also claim the Caroline Islands, Palau, Mariana Islands (today Micronesia), and Samoa (today Western Samoa).17

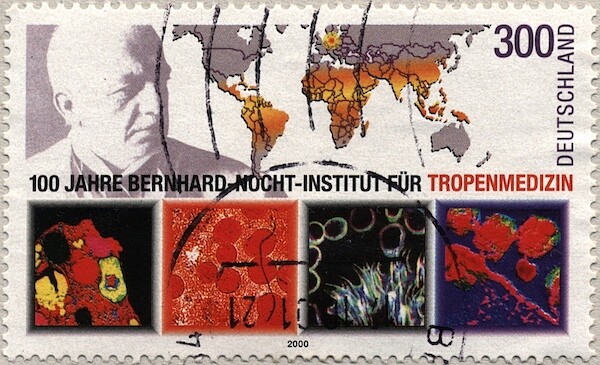

A 2000 German postal stamp commemorates the centennial anniversary of the Bernhard-Nocht-Institut (formerly ISTK) study of Tropical Medicine, marking Hamburg’s position in relation to the tropical geographic zone on the world map. Deutsche Briefmarke zu 100 Jahren Bernhard-Nocht-Institut für Tropenmedizin, 300 Pf., 2000.

The inaugural journal acknowledged earlier publications on tropical illnesses, but it also marked a paradigm shift: “So far, however, there has not been a magazine that continuously collects reports from warm countries, mediates the expression of different opinions, offers information, and encourages observation.” In his opening letter, the editor stated that the aim of Tropical Medicine is to “provide the white race with a home in the tropics.”18 In short, Tropical Medicine was a form of medical geography, wherein the people and climates of the German colonies were pathologized and correlated to infectious diseases such as malaria, yellow fever, and cholera.19 Tropical bodies and conditions were framed as unhealthy in distinction to the norm of the European climate and white European body, even as Europeans living in European climates and environments were subject to the same diseases and could set off epidemics.20

In his journal article, Nocht’s account of the ISTK centers around its service to Tropical Medicine, even though the field still had trouble describing itself. In his opening day speech in May 1914, Nocht admits:

It is not easy to define the field of work of the institute and to describe it in short words, just as it is quite impossible to give a scientific definition of the term tropical diseases. And in recent times, the more our knowledge in this field has expanded and deepened, the boundaries between tropical medicine and other medicine have blurred even further in that general research has become more and more in line with the theoretical point of view tropical diseases too started to employ…Nevertheless, the Tropical Hygiene Institutes have not become superfluous for research either, they will have to seek the boundaries for their field of work preferably in the more or less great practical importance of medical and hygienic questions for the tropics.21

Scottish physician Patrick Manson argued that the categorization of tropical diseases could not correlate to the diseases found in the tropics, for these would be “virtually the whole range of diseases known to mankind.”22 In the Tropical Medicine perspective on health, the ambiguity between climatic conditions and illnesses would mainly play out in the discourse of medicinal practice; however, this ambiguity was also expressed through the materiality of the ISTK building and its own climatic strategies. Given Nocht’s description of the building, its high-pitched roofs and elevated main floor featured in the photographs, it can be reasonably assumed that the building ventilation was planned to conform to European standards of architectural hygiene, rather than to recreate the “tropical” environmental conditions by which the discipline defined itself.23 Only two rooms are noted by Nocht to be climatized to the tropical conditions of its animal inhabitants, those for snakes and insects, located on the top floor of the main building.

The climatic ambivalence of Tropical Medicine did not stop the production of its own pedagogy and etiological theory associated with the tropics. By the end of its opening year, ISTK had “held 38 courses for tropical doctors and prepared over 800 doctors, including many foreigners, for work in the tropics. Courses on nursing for tropical diseases and support for doctors in the laboratory and on practical renovations were also held for nurses, missionaries, and hospital assistants, and lectures on tropical hygiene were given to listeners at the Hamburg Colonial Institute (non-medical professionals) in the winter and summer semesters.”24 To support these programs, the main building of the ISTK featured a course hall, an auditorium, and a museum open to the public. These were located in the western mass that pressed up against the Bernardstraße street front, where tall windows offered passersby long glances into the museum space.

As part of the institute’s agenda to support the expansion of the Empire through teaching and development of new health standards, members of the ISTK contributed to the Deutsches Kolonial Lexikon, a three-volume series completed in 1914 (in the same year as the new ISTK buildings) and published in 1920.25 The three volumes contained maps of the colonies coded to show the areas that were considered “healthy” for Europeans, along with recommended building guidelines for hospitals in the tropics.26 These hospitals were first dedicated to supporting the health of Europeans. “Natives” were given separate facilities (Krankenhäuser für Eingeborene), often constructed using “local” materials, perhaps taking Schumacher’s non-medical definition of health to heart by using vernacular building systems to achieve a “down to earth” sentiment.

The hospital at the ISTK was similarly divided according to identity. An essentializing belief in “intrinsic factors” determined by skin color, constitutive to Tropical Medicine, materialized in the building’s circulation. Potential patients were assessed in the main building to determine their next destination in the hospital. A room labeled “Farbige” (colored)—visible in both Nocht and Schumacher’s publications—shows that the hospital segregated people of color from whites. Whereas people of color were given a street view and northern light, white people were given a sea view and southern light. Separate washrooms were provided for each.

The perceived danger of the “tropical disease” can perhaps best be understood in the ISTK laboratories. According to Nocht, the new building had forty-five laboratories with 103 workspaces, facilitating new types of research including the use of large animals.27 Vitralin, a lead- or zinc-based paint promoted as a hygienic wall covering around 1908, was selected to coat the laboratory walls.28 It was reported to work in two ways. First, it killed germs on its surface—both those which are easily carried “in the air” (such as tuberculosis, typhoid, and diphtheria) and bacteria (such as cholera and the flu) which are carried in moisture but may transfer from people to objects.29 Second, Vitralin sealed the wall substrate, preventing germs from embedding themselves in the dust or particles of the wall. As a sealant, Vitralin ensured that washdown and disinfectant procedures could be carried out effectively.30 Though the toxicity of lead paint—especially to painters working with the material, first in the line of danger through inhalation—was already well known in the early 1900s by medical professionals, the architectural industry did not take up the call to ban lead paint.31 Nocht’s emphasis on the use of Vitralin suggests that, for both him and Schumacher, the ends justified the means.

Choleric Modernism

Despite belonging to two different disciplines, both Nocht and Schumacher’s publications articulate an understanding of health, conceived in material or bodily terms, that is linked to concepts of identity separating white upper-class German Europeans from others. Hamburg had always been an internationally connected city by way of the Hanseatic League, yet recent growth of the shipping industry and overt engagement of the German Empire in colonialism brought even more distant global connections to its port. For Schumacher, Hamburg’s presence in a global network meant it needed to strengthen its local identity and economy, lest it grow too far from its roots.

In the case of Tropical Medicine at the ISTK, the “tropics” seemed to act as a foil for the European identity—a constructed category through which the European identity could redescribe itself by exclusion, especially in the context of people with darker skin tones—rather than as a site for expanded understandings of health in a globally interconnected world. What it meant to be sick or healthy was taken up by both medicine and architecture—each on their own terms, but neither in a vacuum. While Schumacher and Nocht might have expanded the discourse of their respective fields, the ISTK surpassed the rhetorical limits of each discipline—channeling messages of health and healing not only in architectural and medical terms, but also through those of Empire and capital.

The institute is now called the Bernhard Nocht Institute for Tropical Medicine.

Fritz Schumacher, Stufen den Lebens, 297; quoted in Jennifer Jenkins, Provincial Modernity: Local Culture and Liberal Politics in Fin-de-Siècle Hamburg (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2018), 277.

Hamburg Deutscher Architekten und Ingenieur-Vereine (Hamburg Association of German Architects and Engineers), Hamburg und seine Bauten: unter Berücksichtigung der Nachbarstädte Altona und Wandsbek 1914, vol. 1, ed. Merckel (Hamburg: Bonsen und Maasch, 1914).

Bernhard Nocht, “Das Neue Institut Für Schiffs- und Tropenkrankheiten,” Beihefte zum Archiv für Schiffs- und Tropen-Hygiene unter besonderer Berücksichtigung der Pathologie und Therapie 18, no. 5 (May 1914): 8–25.

In his keynote speech at the inaugural meeting of the Deutscher Werkbund in 1907, Schumacher made a case for bolstering the national economy through aesthetics and architecture. “Everything that can be imitated soon loses its value on the international market; only the qualitative values which spring from the inexpressible inner powers of a harmonious culture are inimitable. And consequently there exists in aesthetic power also the highest economic value. After a century devoted to technique and thought, we see the next project which Germany has to fulfill as that of the reconquest of a harmonious culture.” Fritz Schumacher, “Speech at the founding of the Deutscher Werkbund, Munich 1907,” Die Form 7, no. 11 (1932): 330–331. Translation from Ben Farmer, Hentie J. Louw, and Adrian Napper, Companion to Contemporary Architectural Thought (London: Routledge, 1993), 463.

Fritz Schumacher, Grundlagen der Baukunst: Studien zum Beruf des Architekten (Munich: Callwey, 1916), 187.

Fritz Schumacher, “Das Wesen des neuzeitlichen Backsteinbaues, Teil 1: Zur Ästhetik des Backsteinbaues” (Munich, 1920); quoted in Dorothea Roos and Friedmar Voormann, Hamburger Backstein- und Klinkerbauten: Gestalt, Konstruktion, Material (Karlsruhe: KIT Scientific Publishing, 2011), 184. Italics added.

On Schumacher’s work with brick manufacturing, see Jakob Julius Scharvogel, “Neuer Hamburger Backsteinbau,” Dekorative Kunst 20 (1917): 337–346; and Hermann Muthesius, “Fritz Schumachers Bautätigkeit in Hamburg,” Dekorative Kunst 27 (1919): 93–97; both found in Roos and Voormann, Hamburger Backstein- und Klinkerbauten, 171–174.

Fritz Schumacher, “Farbige Architektur,” 1900; in Streifzüge eines Architekten (Jena, 1907), 117–124; found in Roos and Voormann, Hamburger Backstein- und Klinkerbauten, 157.

Muthesius, “Fritz Schumachers Bautätigkeit in Hamburg,” 93–97; found in Roos and Voormann, Hamburger Backstein- und Klinkerbauten, 174.

Schumacher, “Das Wesen des neuzeitlichen Backsteinbaues,” quoted in Roos and Voormann, Hamburger Backstein- und Klinkerbauten, 178.

Caroline Hero et al., UNESCO World Heritage Nomination Dossier: The Speicherstadt and Chilehaus (Hamburg: Free and Hanseatic City of Hamburg, Ministry of Culture/Department for Historic Preservation, 2015), ➝.

“By 1892 Neustadt Sud had the greatest number of accommodations with rent below 300 marks a year, and neighboring parts of town St. Pauli, Neustadt Nord, Altstadt Nort, St. George Nord und Sud had the greatest amount of lodgers per household,” and in the 1890s, almost 70% of the population was below the poverty line. See Richard J. Evans, Death in Hamburg: Society and Politics in the Cholera Years 1830–1910 (New York: Penguin Group USA, 1990), 70–73.

Refer to text and Map 33, “Cholera mortality rate, by district, Hamburg 1892,” in Evans, Death in Hamburg, 420–428.

The Port Medical Service was established immediately after the 1892 cholera epidemic. By 1895 the St. George hospital in Hamburg had 25 beds reserved for “internally ill seafarers”—the “internal” descriptor suggesting travelers and sailors who were European and likely white. When the ISTK was established in 1900 it took on the role of treating seafarers with diseases classified as tropical. Sven Tode and Kathrin Kompisch, “Forschen—Heilen—Lehren: 100 Jahre Hamburger Tropeninstitut,” in Bernhard-Nocht-Institut für Tropenmedizin 1900–2000, eds. Tode and Kompisch (Hamburg: Bernhard-Nocht-Institut für Tropenmedizin, 2000), 8.

After Patrick Manson’s book Manson’s Tropical Diseases: a Manual of the Diseases of Warm Climates (1898) was published, and new institutions in Liverpool (1898) and London (1899) were established. Note that the Hamburg ISTK was not the first hospital treating what were classified at the time as “tropical diseases.” Patrick Manson was involved in the founding of the Hong Kong College of Medicine in 1887, which had built a series of hospitals to treat local patients with diseases classified as tropical, using Western techniques. See Plague, SARS and the Story of Medicine in Hong Kong, ed. Arthur Starling (Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 2006).

Arnulf Scriba, “Statistische Angaben zu den deutschen Kolonien,” Deutsches Historisches Museum, September 17, 2014, ➝.

Beihefte zum Archiv für Schiffs- und Tropen-Hygiene unter besonderer Berücksichtigung der Pathologie und Therapie, 1897–1898, vols. 1–2, ed. Dr C. Mense (Leipzig: J.A. Barth, 1898), 3–4.

Harish Naraindas gives an excellent account of how putrefaction, or the rate at which organic material decomposes in varying climates, formed a basis for this medical pathologization. See Harish Naraindas, “Poisons, Putrescence and the Weather: A Genealogy of the Advent of Tropical Medicine,” Contributions to Indian Sociology 30, no. 1 (1996): 1–35.

Cholera, for example, had been present in both India and Europe since the early 1800s.

Nocht, “Das Neue Institut,” 8–25.

As such, Naraindas argues that the discipline of Tropical Medicine “in a ‘scientific’ sense, was obsolete at the very moment of its founding.” While this may have been epistemologically true, the field nevertheless continued to operate under the aegis of its descriptor “Tropical.” Narindas uses this statement to argue that Tropical Medicine, and “climate” as its operative term, must be seen as a mechanism of “global pathologization.” Naraindas, “Poisons, Putrescence and the Weather,” 1–35. Naraindas quotes Patrick Manson (1898) on page 2.

For standards of architectural hygiene in Europe, see Banister Flight Fletcher and Herbert Phillips Fletcher, Architectural Hygiene: Or, Sanitary Science as Applied to Buildings: A Textbook (London: Whittaker & Company, 1911), 189–190. Though perched on a bank with steep elevation change, the site was leveled into a platform for the building, so that the ground line was consistent around the entire façade, allowing windows below the raised ground floor to pull in air at the basement level. Concern for ventilation in all three of the buildings is perhaps one reason why the main floor is lifted up off the street front, even though this would seem to make it difficult to unload a person from the ambulance to the building in order to carry them into the hospital.

Nocht, “Das Neue Institut,” 8–25.

Deutsches Kolonial Lexikon, vols. 1–3, ed. Heinrich Schnee (Leipzig: Quelle & Meyer, 1920). A photograph of the Hamburg Institute for Tropical Medicine is included in this book.

The Deutsches Kolonial Lexikon has been digitized as part of the Archives of the German Colonial Society by the University Library of Frankfurt am Main. Der Bildbestand der Deutschen Kolonialgesellschaft in der Universitätsbibliothek Frankfurt am Main, ➝.

The construction of an animal house was perceived as particularly important for the ISTK to advance its research. Previous facilities had not had enough space. “Tropical pathology can only be carried out successfully if the study extends to people and animals at the same time, whose diseases in the tropics are closely related.” See Hamburg und seine Bauten, 320.

The first publication on Vitralin appears to be Xylander, “Vitralin, eine desinfizierende Anstrichfarbe. Arbeiten aus dem Kaiserl,” Gesundheitsamte 29, no. 1 (1908).

Hüne, “Beitrag zur Hygiene der Wandanstriche,” Zeitschrift für Hygiene und Infektionskrankheiten, medizinische Mikrobiologie, Immunologie und Virologie 69, no. 1 (1911): 243–66, 244.

“A New Enemy to Germs,” The Chicago Medical Recorder 31, no. 9 (1909).

“The work done in America, Germany, and elsewhere, showing that volatile liquids generally have most deleterious effects on health seems to be recognized only in narrow circles.” Henry E. Armstrong, “Lead Poisoning and the International Labour Conference,” British Medical Journal 2, no. 3181 (1921): 1042.

Sick Architecture is a collaboration between Beatriz Colomina, e-flux Architecture, CIVA Brussels, and the Princeton University Ph.D. Program in the History and Theory of Architecture, with the support of the Rapid Response David A. Gardner ’69 Magic Grant from the Humanities Council and the Program in Media and Modernity at Princeton University.