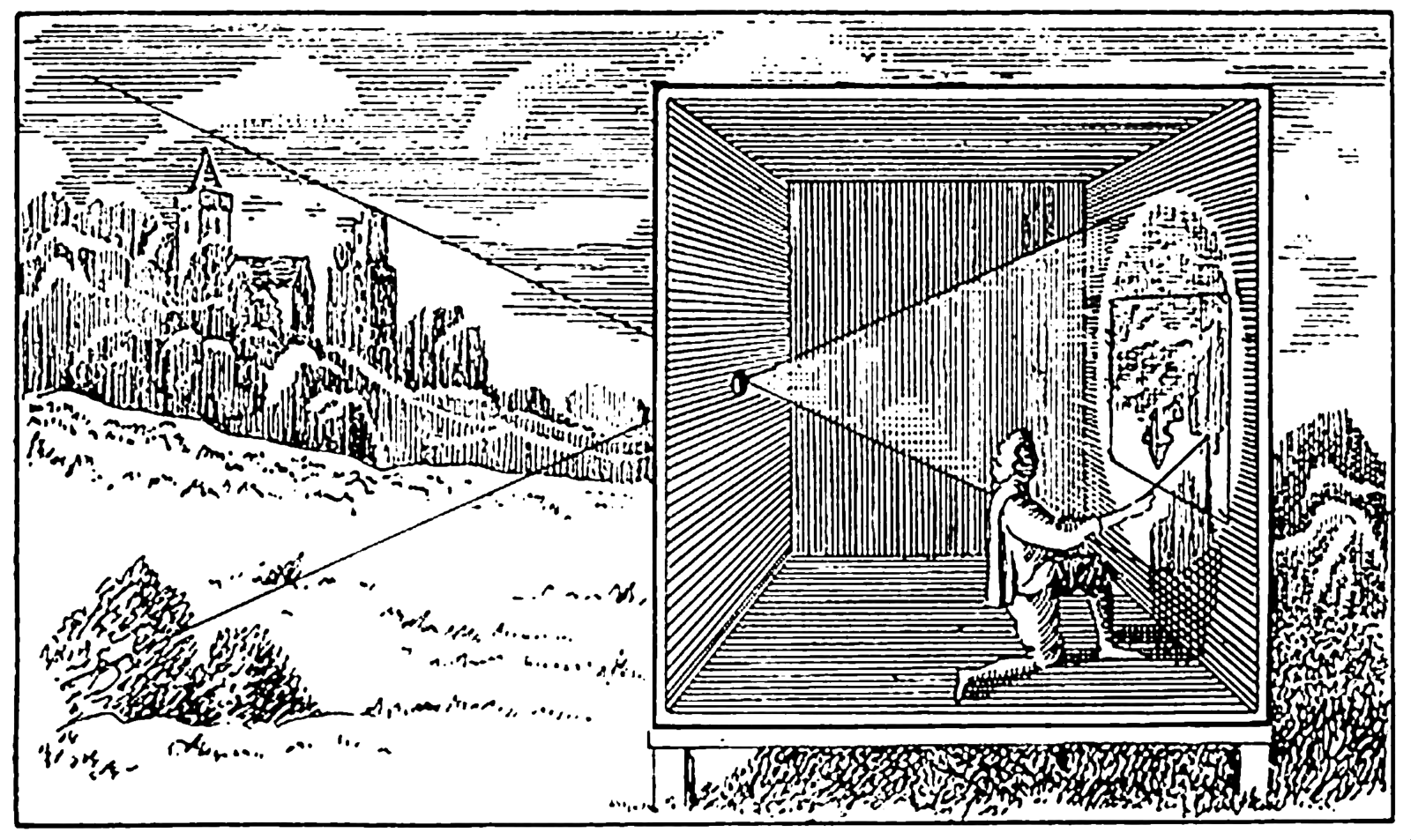

In her classic work on The Concept of Representation, political theorist Hanna Pitkin draws upon the meaning of the Latin verb repraesentare—to show, to exhibit, to bring before oneself—in order to offer a tentative definition of representation as making present again, or as she writes, “the making present in some sense of something which is nevertheless not present literally or in fact.”1 Immediately, Pitkin notes, this definition sets up a paradox: for one cannot claim that something is both present and not present at the same time. Nevertheless, it is the paradoxical nature of the concept that sustains it in the political realm, since both political subjects and their representatives must work together to ensure a kind of mutual autonomy. The absent constituent delegates responsibility to the present representative and the representative in turn is entrusted with the will of the constituent; though they substitute for one another, they are kept in suspense.

What do architectural and political representations share? Perhaps we could think of the relationship between architects and their clients as a variant of Pitkin’s paradox, although architects and political representatives are selected, or assume their representative roles in very different ways—legal representation might be a closer analogy here. In its constructed form, architecture has often been used as a representation of political power in order to both reify and augment it. We could think of both democratic spaces—forums, squares, places for public debate—or in the case of a fascist ideology—monuments, tombs, or various forms that allude to the sacrifice of the individual. However, architectural representation, in its most common sense, as the medium, or media, through which architecture is visualized and projected, falls under another category entirely since that which is represented is not an absent political subject or constituent, but architecture itself.

This is not to say that architectural representation, or representation produced in advance of some future act of construction, is outside of the realm of politics; rather, we would have to ask different questions about the kinds of power that are exercised when architects make things in order to address their political dimension. What are the politics of the architectural imagination, for instance? Who has access to creativity during a process of design? How is it exercised and implemented, and to what end?

The architectural drawing set is a particular type of representation from which the social dynamics of everyday architectural work are most visible, or readable, and where answers to some of these questions might lie. While a construction site or staged demolition, or even an outwardly apparent process of model making, would seem to offer a complete vantage point onto architectural work, a physical assembly or deconstruction of a building would not tell you much about how and where it was drawn. The drawing set, more than any other form of drawing, reconstitutes the whole network of architectural participants, even as its inscriptions are continually debated and revised. Here, practices of omission and abbreviation, what I am calling shortcuts, have structured the everyday communication of architects in the field. If architecture is literally hinged upon a series of details and joints, the shortcuts that are employed within its final representation only serve to draw these moments of exception more closely together, while simultaneously establishing, and then bracketing, those parts that are continuous, redundant, or expected. Together, they comprise a system of elision that has had real effects both in the day-to-day transmissions of architectural information and upon the form and perception of architecture itself.

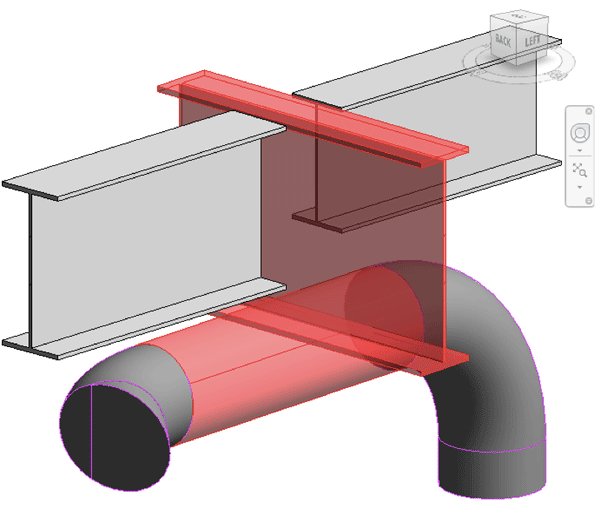

Though we may now recognize the integration of different types of architectural expertise as a visible quality of Building Information Models, where clashes have been, supposedly, eradicated, and specializations coexist in harmony, in the older artifact of the drawing set, the blank and often overlooked spaces of the page establish a different kind of integrity, known in the relations of senders and receivers, writers and readers, rather than in the finite boundaries of a singular object. They make present something, which is nevertheless not present literally or in fact.

Screenshot of Autodesk Revit Clash Detection Feature.

The Two-Handed Method

Passing through the studios of architecture schools amidst the perennial frenzy of charrette, one is likely to encounter an increasingly familiar scene: the student seated at their desk, one hand combing through a pile of delicate cardboard or plastic cut-outs, and the other sliding and rolling the cursor of a mouse in an effort to locate these fragments within the digital interface of a three-dimensional model. In this miniature construction site, the two hands are not counterbalancing one another or even multi-tasking; instead, they connect the pile and the model, as the student attempts to bring these real and virtual realms into closer correspondence.

At times, this activity is so consuming that the separation between these realms is forgotten altogether. Though the cut-outs may be singed along their edges or sharp to the touch, their status is much more provisional than that of the fully constituted, yet immaterial, model that serves as both the guide and measure for each act of assembly. If there has been an accounting error, the student undoubtedly will exclaim, “I am missing a piece!” casting a look of dejection towards the insufficient pile, rather than accusing the virtual model of being excessive in its quantity. And though there are numerous examples, and occasional myths, of the kinds of fortuitous accidents that occur during this much more contingent phase of physical model making, we must acknowledge that the harried student (or, in a more official setting, the expert fabricator) is an executor, fully absorbed in the laborious and administrative activity of preparing files that will be processed, later, by machines.2

This habit of working must lead to some form of satisfaction. Term after term, in diverse schools and studios, often without a formal imperative, and occasionally in spite of the protestations of those instructors who promote an older method of using working models, imagining them as sites of chance and circumstance, the “two-handed method” prevails. Perhaps its attraction lies in the promise of a whole; while panning around the outside of a virtual model, one imagines that the work has an end in sight. The model appears right away, ready to be manipulated through a series of commands. These processes are completely reversible—the model retains a history of every action and movement of the camera. One can begin at any scale—the nondescript background provides no visible references or points of departure. Twisting and pulling the virtual form with the cursor, the modeler works by proxy, never zooming far enough to penetrate the visible surfaces or to become immersed in their material substance.

In periods of boredom or frustration, brought about by this unending exteriority, the modeler begins to orbit around the object, seeking entry even as this passive rotation creates the illusion of transformation and development. Even if rotation has long been a crucial feature of projective drawing, it has lost its generative capacity in this context, more often lulling the modeler into a state of hypnosis rather than allowing for creative progression in the work. Eventually the spinning ceases, the restless object is locked into a fixed location, and a function within the software allows the architect to extract the desired “line-work”—a form of instantaneous drawing in which the lines are found latent in the object, rather than produced in its anticipation.3

Screenshot of Sam Fox School of Design and Visual Arts promotional video, Spectroplexus, 2017.

Here, the model no longer serves as a potential representation of what it might become, and a device at the service of one’s designs: instead it is fully reified. When one speaks of “building the model,” as opposed to “modeling the building,” it is clear that the digital file has been settled and is no longer a source of future speculation. Indeed, this method necessarily involves a full stop of one representational activity before the next one can begin; the digital model must be known in its entirety before it can be pulled apart, flattened, reformatted, and reconstituted once again to scale. And even when this second model or extracted drawing—token prints, sometimes in a literal sense—are produced, their gaps and fractures are not so much mysterious lacunae as evidence of a loss of tolerance, signaling back to a more total version of the work.4

This scenario, which is now a common recurrence within contemporary architecture schools and offices alike, serves here as a point of departure from a history of shortcuts within architectural drawing that have relied upon shared assumptions, inference, and partial views of the whole. The orbiting perspective of the “fully-integrated” object, much like forms of aerial and satellite photography, assumes a totality that is contradicted by the detailed experience of the draftsperson in the field.

Here we find the architect in medias res, employing an ensemble of practices in order both to comprehend and transmit information within a restricted economy of working hours and graphic space. Shortcuts such as the break line, the partial fill, and the spaces between the pages of a drawing set have been crucial in allowing architects to skip ahead and trail off while tracking the contours of a project. These techniques are consequential, not because they have allowed architects to approach an imagined totality, but rather because they have continually reinforced the limits of tacit and explicit architectural knowledge. A taxonomy of shortcuts shows how they are both linked to other experiences of writing and reading, making and interpreting, presenting and beholding, and, at the same time, unique to architectural work. As the conditions that allowed them to take hold within architectural representation disappear, what role will these artifacts play in the future of drawing?

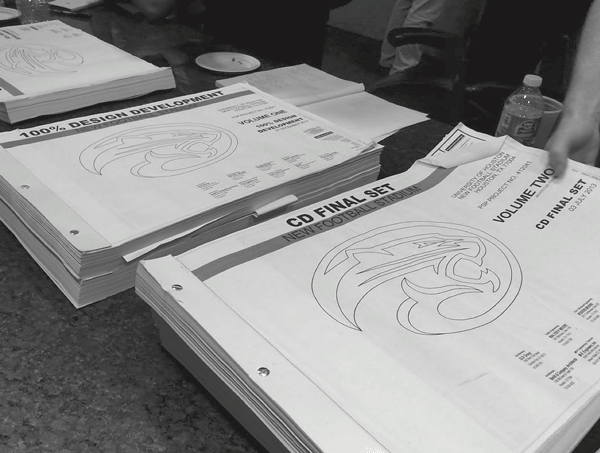

Photograph of Page Southerland Page offices, Houston, Texas, 2015.

A Detour

It may be useful to pause here to consider a more general definition of the shortcut before addressing its architectural context. When one crosses on an angle, leaps over a fence, or makes a beeline for an exit, they are realizing a spatial solution to a temporal problem; namely the problem of arriving at a desired destination within a limited amount of time, while forgoing all of the experiences that the long route might offer. The shortcut, therefore, is always understood as an abbreviation of a more thorough, required path, and as such, often carries with it the negative connotation of skipping steps and cutting corners. At the outset of The Phenomenology of Spirit, Hegel describes the incompatibility of the preface—typically an explanation of aims, and comparison with past works—with the “way in which to expound philosophical truth,” writing that although philosophy moves “in the element of universality,” one cannot omit or skip over the particular, since each argument and counterargument takes part in an organic unity that must be worked through in sequence.5 In circumventing the central purpose of philosophical inquiry, the shortcut—here the generalizing nature of prefatory remarks—is understood as counterproductive, if not a false step entirely.

And yet, if we consider shortcuts in settings where no such unity exists, we might also think of them as more than absences and omissions, but rather as creative acts in their own right, providing clearings through what was otherwise closed or hidden. Michel de Certeau’s use of the term in The Practice of Everyday Life is closest to this meaning; here the shortcut is found among a repertoire of “tactics” as the walker moves through the “spatial order” of the city. Rather than merely taking open routes, or being hindered by physical obstacles, de Certeau’s walker improvises, and in doing so “condemns certain planes to inertia or disappearance and composes with others spatial ‘turns of phrase’ that are ‘rare,’ ‘accidental’ or illegitimate.”6 Once the shortcut has been performed, it is soon taken up again, contributing to what he describes as the “chorus of pedestrian enunciations” that make up the rhetoric of walking.

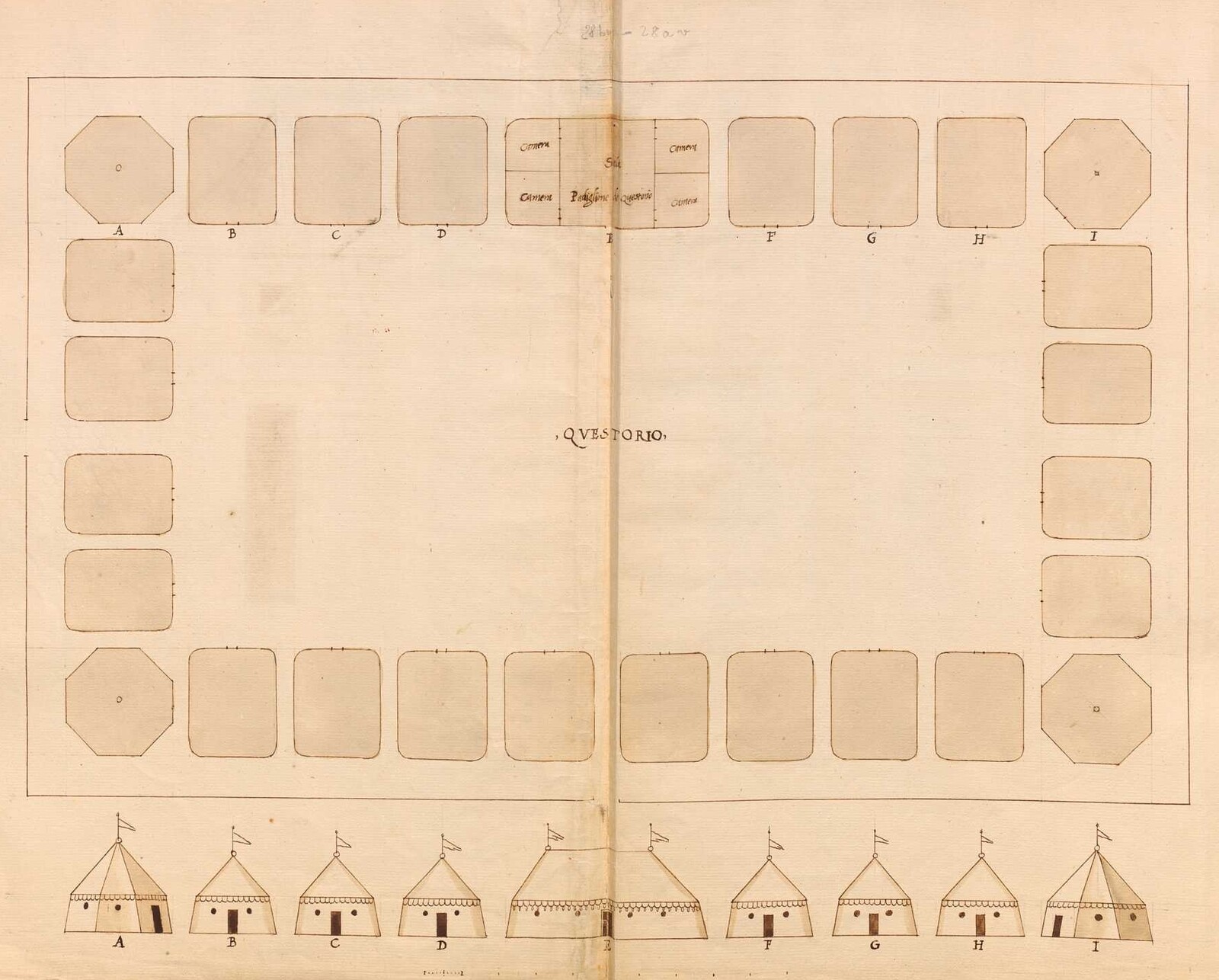

It is this improvisational and interpretive sense of the shortcut that has chiefly concerned architects, who, in attempts to anticipate both formal and informal trajectories through their imagined spaces, make room for the opportunistic and spontaneous movements that de Certeau celebrates in everyday life. But architectural representation also takes place in space and over time, and architects themselves exercise forms of improvisation and spontaneity in the day-to-day work of producing architecture. Could the whole project of architectural representation be understood not as a gap or delay between thinking and making, but as a massive shortcut—a heuristic device that allows for direct access to a history of shared knowledge, a network of readers and writers, and an inventory of graphic resources that correspond to equipment, materials, and processes, which extend beyond the boundaries of the digital window or the drawing board? When these drawings are themselves abbreviated or edited for concision, are these not invitations to cut to the chase, taken with the same enthusiasm as a secret byway?

Drawing Sets at Page Southerland Page, Houston, Texas, 2015.

A System of Elision

When one makes a naïve comparison between the size of a building and the size of its drawing set, reversing the familiar direction of architectural projection in order to ask how a building might fit back into its documents, it becomes clear that the compression of architecture is not merely achieved through the use of scale. If it were a product of scale, we might imagine that a building could grow at a constant rate out of its reduced graphic material, swelling out like a sponge in water, or as Robin Evans has fantasized, “sprouting thousands of imaginary orthogonals from its surface.”7 Perhaps a better, though incomplete analogy, is to an umbrella, which telescopes, folds, and collapses at its hinges, breaking down into a reduced version of itself, while simultaneously concealing its capacity for expansion.8 How, then, might we unpack the compressed artifact of the drawing set, finding in its general progression the relationships between parts of the building described therein?

Though there is no universal format for the documentation of a work of architecture—indeed, most works of architecture are not documented at all—we could say that drawing sets are, for the most part, alike in that they are organized in a sequence from general to specific information, and in scale from the most comprehensive representations to the most enlarged details. Writing on “Scales of Representation,” Vittorio Gregotti has noticed that “the various scales are not just instructions for building or reduced representations of an object pre-existing in imagination or reality, but function as different ‘calligraphies,’ with different levels of enquiry for the construction of the architectural object.”9 Each scale offers a distinct entry point into the conception of a building that corresponds to different levels of determination in drawing. Often an architect will begin to design at a scale that is detailed enough to require a certain amount of precision, but not so enlarged that they become overly fixated on a particular section.

At a very blown-up scale, one may lose a sense of the surrounding context, leading to a prototypical quality in the overall design.10 In this myopic form of drawing, the architect is unable to work loosely; the detailed scale demands a level of control that precludes casual gestures. Here, too, drawing conventions—required dimensions, determined line-weights, construction specifications—enter the work. The architect, in this context, gradually defines the border of an imagined space, speeding up when a standard can be applied, and slowing down when an unprecedented combination of materials requires new thinking. Even the inversion between scale and the represented object seems to produce specific effects—larger scales are used for smaller objects and smaller scales for larger objects. As a result, architects are always scaling away from their buildings, just as the drawings increase in definition.

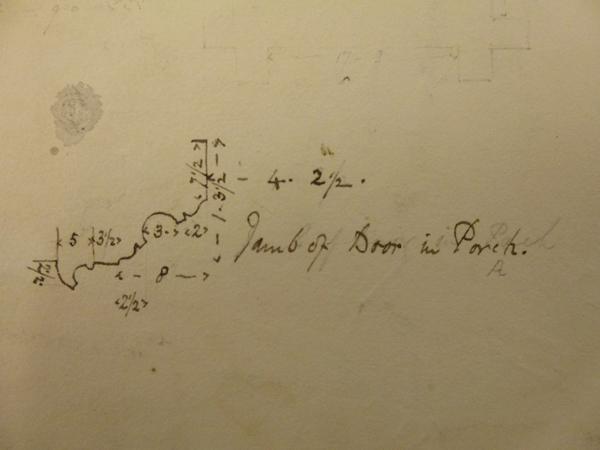

Adding to this disorientation is the fact that drawings within a set do not enlarge with a singular focus, but rather oscillate between different planes of projection while splintering off in many directions in order to describe multiple aspects or areas within a project. As construction drawings become more detailed towards the back of the set, they also break apart into more and more fragmentary forms, just as their explanatory notations increase in density and specification. Consider, for example, the last pages of Louis Kahn’s set describing the Exeter Library from 1968, in which someone has composed all of the sills, lintels and jambs of the building in a dense matrix.

All of these details bear certain resemblances in their drawing style and in their represented content, even though they are located at a great distance from each other relative to the size of the building. The layout of these fragments has little to do with the organization of the plan, but the pieces maintain their true positions in relation to one another and their truncated edges suggest that they are connected even if much has been omitted.

Without the seamless fades of another medium like film, or explicit statements of transition in a narrative, how is an architect able to establish continuity within the variety of the set? How can each of these symbolic representations to be understood as belonging together even as they are accessed independently? In narrative forms, when there is a misalignment between the time of the story and the time of the narration, we can point to specific devices such as analepsis and prolepsis, flashbacks and flashforwards, that accelerate, slow down, or create anachronisms within the sequential recounting of events, complicating the relation between these two speeds. In a drawing set, there is no single diachronic progression through the various representations, even if each drawing was produced over the duration of some time span, and ultimately anticipates a longer process of construction that has a beginning, middle, and end. Just as a multitude of drafters might be involved in the assembly of the set, working synchronically at different scales and within different zones of the project, a multitude of readers—builders, consultants and other architects—might pore over distinct sections with different ends in mind, entering copies of the set simultaneously via its index or table of contents. In the most extreme cases, in which the technical complexity of a building outpaces any single reader’s ability to grasp every feature, the set may only be known through its fragments. It is here that the projected work takes on the features of what Bruno Latour has called “risky objects,” those that “overflow their makers” and whose connections are revealed only after they have been disassembled.11

The comprehension of construction drawings is, therefore, neither progressive in the way one might steadily traverse a conventional novel, nor global in the way that one spreads out and then scans over a map all at once. Instead it requires saccadic motions as the reader flips back and forth between views and between scales, checking these representations against one another in order to build up a more synthetic and imaginary version of the work. At each graphic stop, the architectural reader recalls the previous image, remembers the location of smaller details within larger drawings, and extends the abbreviated edges of blown-up fragments into familiar contours and boundaries. Through this constant cross-referencing, a more total image of the object comes into view, confirming certain hypotheses and contradicting others as the architect goes about the workaday activity of piecing together the received representations of others.12

Door jamb detail from William Butterfield, Shottesbrooke Church, 1844. Source: Getty Research Institute.

Broken Drawings

Unlike the aforementioned student, who is engaged in the self-fulfilling challenge of producing an exact replica of a design already realized in virtual form, the architect in the social and professional context just described must call upon a much wider array of conceptual tools, considering not only the most likely meaning conveyed by this collection of foreign drawings, but also alternative possibilities to a work that is still in formation. This distinction could be alternately described as one between an architectural idiolect—a private language that is invented on occasion and is intrinsic to the speaker—and a set of shared practices that are not entirely universal, but which more closely align through the day-to-day production, exchange, and reception of drawings in the field.

Although the working representations of buildings consist of discrete parts that can be combined according to systematic rules, and are therefore language-like, they are distinct from linguistic systems in that they maintain a resemblance to the objects and properties that they represent—the signs of a drawing are not arbitrary and their combinatorial possibilities are not infinite. In this sense they are closer to maps than language or photographs, falling within a continuum between the pictorial and diagrammatic. Like maps, they maintain formal rules of inference that depend upon a reader who can follow along.13

Evidence of these rules can be found not in the symbolic representations themselves, but in what these drawings leave out, and consequently what is conceptually filled in. When an architect flips between a plan and its details, they are crossing over what narrative theorist Gerard Génette has called “implicit ellipses”: “those [descriptive pauses] whose very presence is not announced in the text and which the reader can infer only from some lacuna or gap in narrative continuity.”14 In the case of a drawing set, which is ordered not by chronology but by scale, the sudden leap between a large and small drawing assumes all of the scales in between. A wall that is drawn with a slight inflection at the most comprehensive scale will retain that inflection in its detail, allowing the reader to infer that the drawings correspond. Similarly, when turning from a plan to its section, or vice versa, one assumes that these limited views do not merely represent unique instances within a series of differences, but rather establish a rule that is carried out in every instance.

The base assumption that a drawing set represents the project in full guides the work from its very outset. When an architect draws a single line across a blank page, in the context of the production of a construction drawing, the line is already understood as an edge within a plane of projection, bounding some material, space, or site even if its scale has yet to be determined. And once a second line is drawn, crossing through the first, or perhaps travelling alongside it, it carries with it a whole host of potential associations—the width of a corridor, the thickness of a floor, the spacing of two beams—that are as much a product of the circumstances of architectural drawing as that of any inherent quality of the line itself.

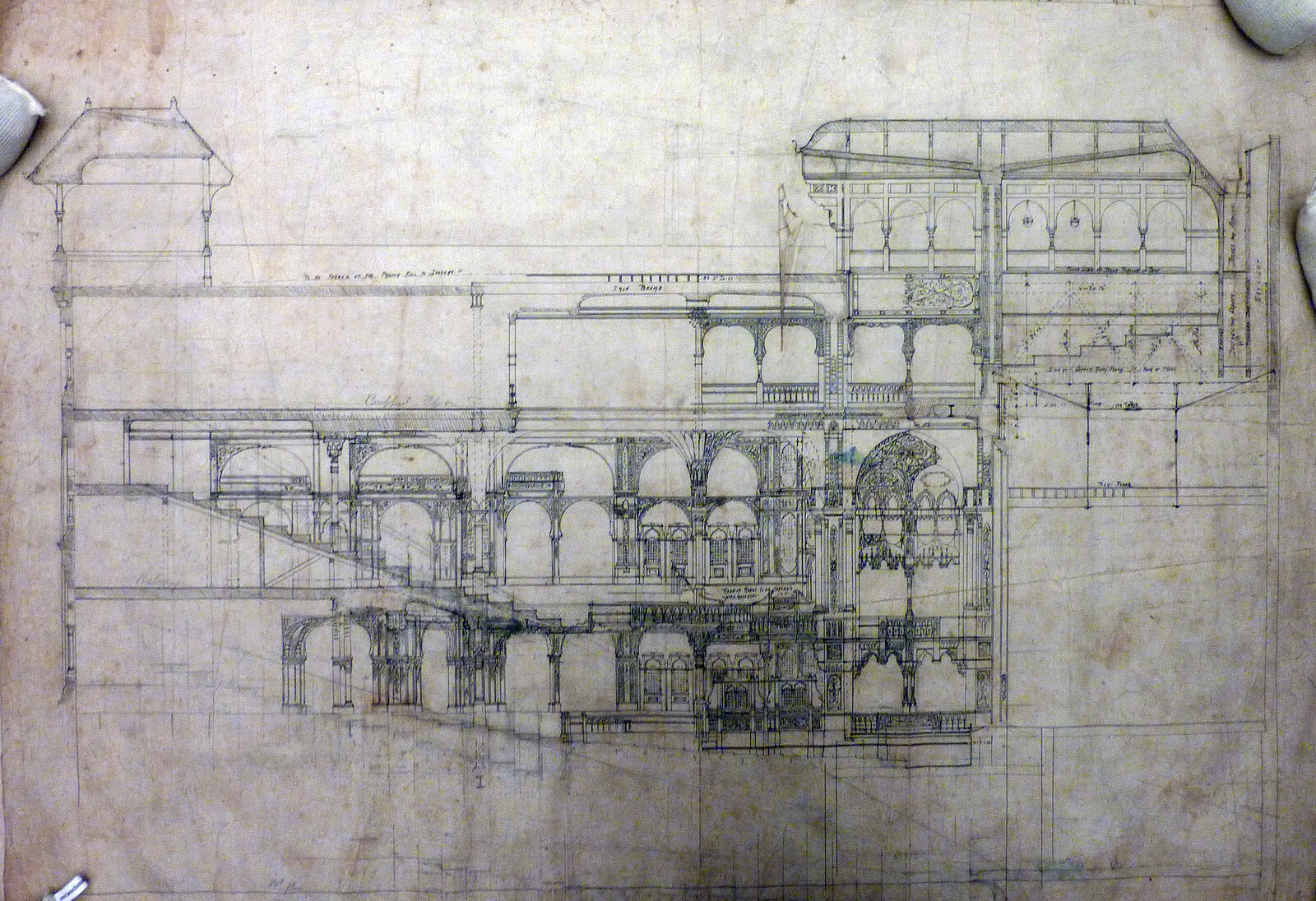

Though these pre-conditions might seem to overdetermine the work, they could also be understood as a loophole that has allowed architects to escape the burdens of total representation through implication. In hand-drawn elevations of elaborate interiors from the turn of the century, such as Kimball and Wisedell’s Casino Theater from 1882, only a portion of the detail is filled in, trailing off at the edges or stopping short at a line of symmetry in order to suggest that the pattern continues throughout. In these areas of incompletion, the representation of the theater resembles processes of construction and ruination that prefigure and outlast the finite and exact version of the project that is promised in its model form. The indeterminacy of these edges signal that the work remains unfinished, as if the draftspersons reached a point of exhaustion, set down their implements, and walked away from their desks. This practice occurs when the drawing subject is so intricate—the filigree of ironwork, or repetitive plaster molding, for instance—or unique to a state in nature—the aggregate composition of gravel, or veins in a slab of marble—that its representation would signify a certain obsessiveness on the part of the draftsperson rather than any essential aspects of its content.

Kimball and Wisedell, Casino Theater, New York, New York. Longitudinal Section, circa 1882. Source: Casino Theatre architectural drawings, Department of Drawings & Archives, Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library, Columbia University.

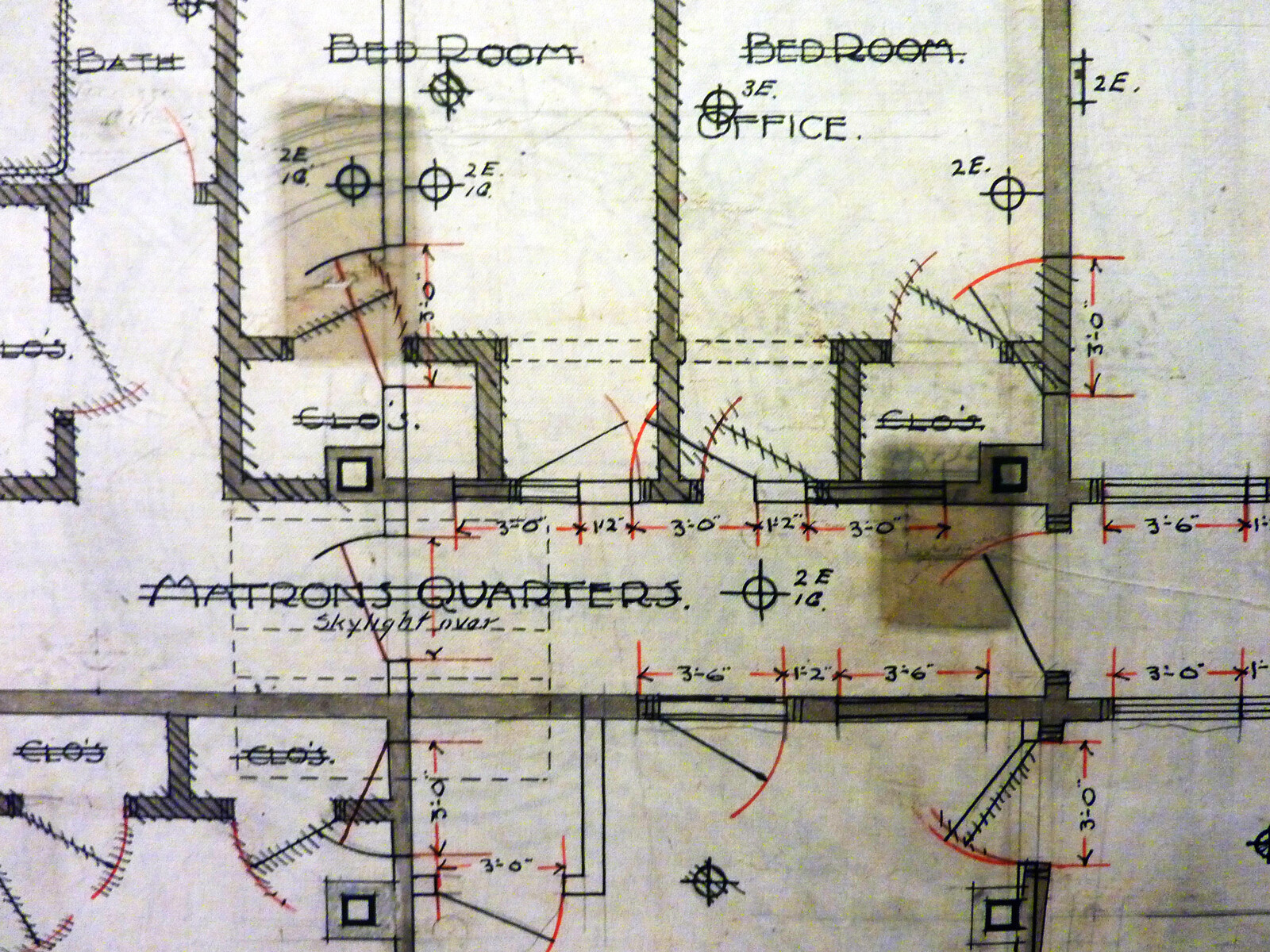

Detail of Hoppin & Koen, Building for Police Department of the City of New York, New York, New York. Second story plan, 1903. Source: Hoppin & Koen architectural drawings, Department of Drawings & Archives, Avery Architectural and Fine Arts Library, Columbia University.

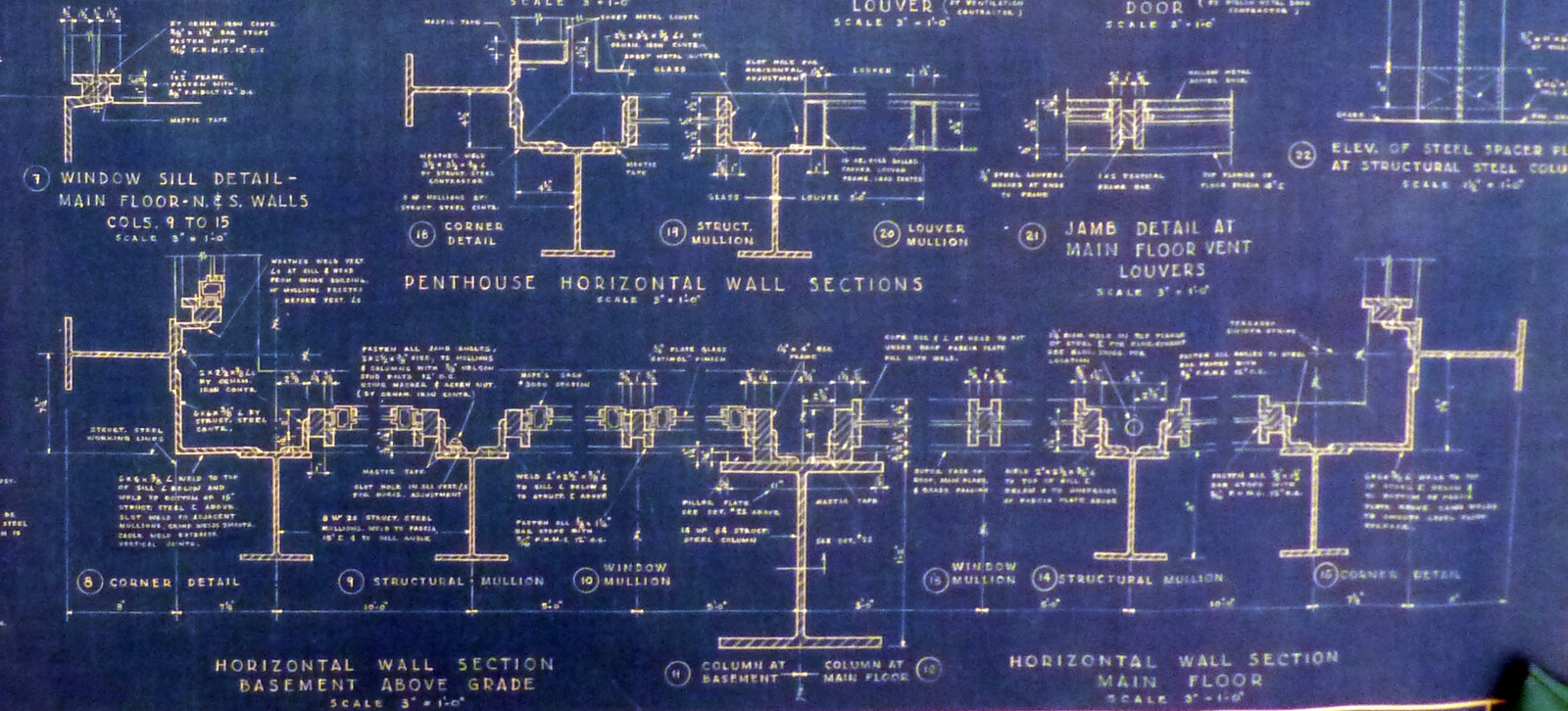

Detail of Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, Illinois Institute of Technology, New Technological Center, Architecture, Design and Planning Building, Chicago, Illinois. Horizontal Wall Section Details, 1954. Source: Ludwig Mies van der Rohe architectural and furniture drawings, 1946-1961. Located in Columbia University, Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library, Department of Drawings & Archives.

Kimball and Wisedell, Casino Theater, New York, New York. Longitudinal Section, circa 1882. Source: Casino Theatre architectural drawings, Department of Drawings & Archives, Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library, Columbia University.

The enormity of this kind of undertaking can be illustrated as well by Hoppin and Koen’s set for the New York City Police Department Headquarters from 1903. These twelve-foot long plans, sections, and elevations were meant to convey every type of information in the same frame—from structure to ornament, and even mechanical equipment. Because it was not feasible to start over, many of them appear as a palimpsest of revisions; whole sections are moved, renamed, and taped over. Some of these drawings are almost unreadable since there have been so many alterations. In the act of revision, these architects have introduced an entirely new set of marks onto the page—strikethroughs and cross-outs—and even with the aid of these notations we can’t always tell what is first and last.

If we compare these long rolls to Buchman and Fox’s National Bank drawings from 1911, it is clear that drawing labor was becoming more distributed. The National Bank set was broken up into a series of smaller drawings with very specific subjects that could be linked through common references and annotations. The inclusion of separate sets of details by consultants reveals a level of coordination and fragmentation between technical organizations that would only increase as building projects became more complex in the first decades of the twentieth century.15

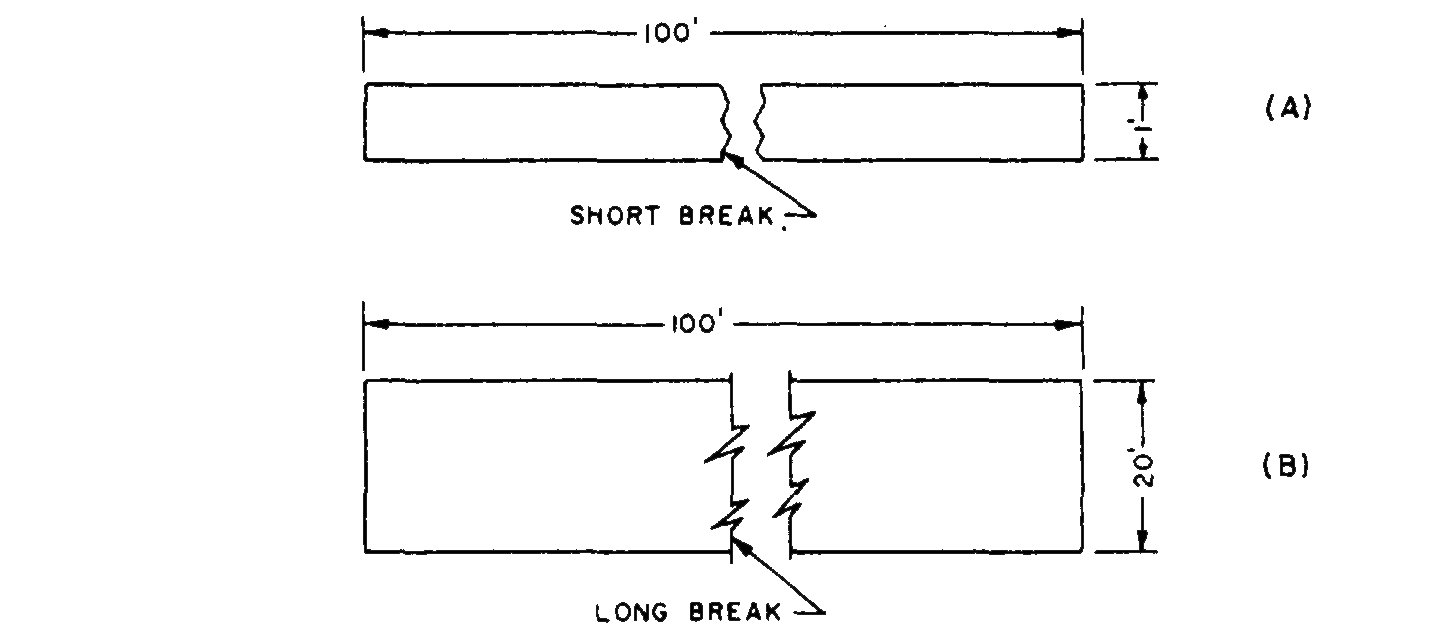

In contrast to the Hoppin and Koen drawing sets, Mies van der Rohe’s working drawings of Crown Hall from 1954 are extremely reduced, presenting a dense array of details separated by break lines that is completely unlike the expansive experience of the hall itself. Like an “explicit ellipsis” from Gennette’s categories, or Gregory Bateson’s “slash mark” in his definition of communicative patterns, the break line is an overt statement that some information is missing—the graphic equivalent of “several days later” or “…”16 This device often occurs at the most enlarged scales of representation in order to relate details within a common frame.17 In a text, we might interpret the ellipsis as a significant absence—a mystery that is not elucidated by the narration and which creates suspense.18 A break line, conversely, brackets extrusions—the pane of a window, the shaft of a column—in which the material and method of construction are so uniform that they fall within existing structures of expectation.

Without these continuous and repetitive parts, however, the metonymic representations of architecture at this scale lose their real proportions, resembling instead cramped and stunted forms that have been cut down through successive waves of editing and concision. In a popular drafting guide from 1920, Edwin Mather Wyatt makes note of an obvious discrepancy between the “broken” representation of compressed details and the intended form of construction: “Draftsmen very frequently draw objects represented as though they had gone through some serious accident,” he writes. “[T]hey represent the objects as being broken… Sometimes an end is broken off, often the part broken out is in the center. The draftsman does not want the workman to make the object broken as represented, but the break is put in the drawing simply as a convenience to the draftsman.”19 Here we might interpret “the break” not only as a graphic intervention but also as an increment of saved time—a “convenience” to the draftsman at the expense of the confusion of the workman. Having reached the necessary and sufficient conditions of description—conditions that are only established afterwards through the repetition of this breaking practice—the draftsperson is able to move on to the next task at hand.

Phenomenology of the Drawing Set

What, then, do we see when we look at architecture that has been drawn in this way, and what do we experience when we move through it? Do we take the same shortcuts in our phenomenal perception of these spaces, glancing from detail to detail as we gloss over the visible surfaces before us? Or do these moments of exception recede into the periphery of our vision as our eyes rest upon the blank areas in between, absorbed in the broad expanses of space that have been elided in the set and complex variation of materials which have only been coded in the drawings? Over time, our awareness of this articulation might wear off, as it is replaced by an embodied comprehension, which gradually substitutes our optical attention. When we brace our legs for a landing, or when we tilt our heads forward while entering a low hallway, we make our own elisions, combining stair and floor, wall and ceiling, through continuous motions that might have less to do with the assembly of these individual architectural elements than the habits they afford.

Like the resourceful walker, who departs from the known path whenever a more expedient alternative arises, the architect in the late stages of drawing is always on the lookout for gratuitous representations that have yet to be packed away, or made to disappear within the loopholes of the drawing set. And just as the abbreviations of the walker are quickly incorporated into a routine, the draftsperson in this context develops methods of shorthand that are soon performed again without thinking. What appears is that which is contested; what disappears is that which has been taken for granted.

This dynamic between the creative and mechanical, the thought and unthought, points to the possibility of two planes of knowledge in an architectural drawing: an active surface that enables interpretation and debate, and a second level that is more universally understood, and therefore unrepresented. The shortcut emerges as an interpretive practice of moving between the two: through explicit notations, strategic omissions, and unfinished patterns, the architect sends foreground information into the background while simultaneously motivating the reader to summon this background into the visible present.

Hanna Pitkin. The Concept of Representation. (University of California Press: Berkeley and Los Angeles, 1967) 8.

From Filippo Brunelleschi’s cracked egg for the Duomo in Florence to Rem Koolhaas’ repurposing of a house for a private client into an entry for the Porto Opera, creativity myths in architecture often seem to revolve around the working model as a site of invention and surprise during periods of competition.

This description is based upon the Non-Uniform Rational B-Spline (NURBs) modeling software, Rhinoceros 3d, which was originally developed by Robert McNeel and Associates in 1992 as a plugin for AutoCAD. Since the release of Rhinoceros 1.0 in 1998, this software has become one of the most widely used tools for modeling in professional architecture schools. The feature of automatic drawing capture, or Make2d, has reversed the traditional sequence of design, allowing the architect to produce a model first and then to extract two-dimensional plans and sections as well as perspective and isometric drawings. The term “line-work,” originally used in the context of lithographic printing to describe the concrete labor of working over sections or layers of an image with line-making implements, such as crosshatching, here refers to the solution of a hidden line-removal algorithm.

I have used “total” to refer to forms of architectural representation that aspire towards an exhaustive description of their objects, even if this totality is short lived or never realized. Limit cases of representational totality can be found within the realm of fiction, such as Jorge Luis Borges’ map at the scale of the territory, or Jonathan Swift’s Lagadonian language professors, who, in Gulliver’s Travels, abolish words altogether, decreeing that it would be more expedient for each member of their society to carry, at all times and in large packs, the very things which they would like to refer to. Jorge Luis Borges “On Exactitude in Science.” (1946), in Collected Fictions trans. Andrew Hurley (New York: Viking Penguin, 1998), 325. Jonathan Swift, Gulliver’s Travels (Mineola, New York: Dover, (1726) 1996) 137.

G.W.F. Hegel, The Phenomenology of Spirit, trans. A.V. Miller, (New York: Oxford University Press, 1977), 1.

Michel de Certeau, The Practice of Everyday Life, trans. S.F. Rendall (Berkeley, California: University of California Press, 1984), 98-99.

Robin Evans, “Translations from Drawing to Building,” AA Files 12 (1986), 12.

Incomplete in the sense that this analogy rests upon a correspondence between the mechanical nature of architectural documentation, performed through divisions of labor and partial forms of expertise that are themselves indexed in the separation of drawings (and by extension the separation of building components) and a mechanical object that is assembled from discrete parts. To put forward an alternative analogy of expansion or compression between the drawing and building (or to do away with one of these two poles entirely) one would have to rethink fundamentally the routines and procedures of architectural work.

Vittorio Gregotti. “Scale della Rappresentazione,” Casabella 48, 504 (July 1984), 3.

If a drawing is produced beyond a 1:1 scale, the design will usually anticipate a form of construction that requires extreme precision. The full scale could be thought of as a kind of professional threshold in this sense; beyond this level of detail, architecture borders on the material sciences. At a much smaller scale, the architectural drawing reaches another kind of limit as it begins to assume the characteristics of cartography. The 1:4000 site plan may have the quality of a small map, depicting the relationship between a building and the surrounding city or landscape. Beyond this distant scale, the outline of the architectural figure is abstracted into a single locative symbol. The plan becomes a map at the moment when it loses its ability to demarcate space, falling out of correspondence with its larger scale versions.

Bruno Latour. “From RealPolitik To Dingpolitik Or How To Make Things Public.” in Making Things Public: Atmospheres Of Democracy, eds. Bruno Latour and Peter Weibel (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2005). Elsewhere, Latour has grouped “engineering drawings” within his category of “inscriptions”- those visible documents that possess the qualities of being mobile, immutable, presentable, readable and combinable with one another. Despite their mundaneness- their presence in everyday routines that are “close to the eye”- inscriptions emerge in Latour’s account as powerful mediators that prompt debate and communication between actors, making what is elsewhere present and what is fictional real within the “optically consistent” space of the page. Bruno Latour, “Drawing Things Together,” in Representation in Scientific Practice, eds. Michael Lynch and Steve Woolgar (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1990), 19–68. While working drawings would seem to serve as ideal nodes within an Actor Network Theory of the production of architecture, ANT’s emphasis on the visible features of objects might overlook the productive absences or ellipses that I have attempted to describe in this paper. For example, Albena Yaneva’s now well-known observational study of modeling practices at the Office for Metropolitan Architecture in 2001 focuses entirely on outwardly apparent debates concerning physical working models in an effort to show how different scales of resolution determine different possibilities for design. Through foregrounding the design meeting as well as more informal, and recordable, conversations between workers, Yaneva misses the non-verbal and virtual interactions that occur within shared files, over email correspondence, and through the protocols of architectural documentation that exist outside of the particular ethnographic histories of each project. Albena Yaneva, “Scaling Up and Down: Extraction Trials in Architectural Design,” Social Studies of Science 35, 6 (2005).

A more dramatic example of this kind of saccadic comprehension is presented in the culminating scene of Michelangelo Antonioni’s Blow-Up, in which David Hemmings carries out a forensic pin-up on the back wall of his apartment. Acting on a hunch, Hemmings continues to enlarge a single photograph of a park scene, juxtaposing and cross-referencing each version of the photograph until he is able to piece together the events of a murder. Hemmings looks away from the image between each act of enlargement, shuttling more and more quickly between the impromptu gallery and the darkroom. It is in these periods of transit that the relationship between the multiple scales of the photograph becomes apparent to the photographer, only to be confirmed for the viewer in one final blow-up. Blow-Up. dir. Michelangelo Antonioni. (Italy, UK: Warner Bros. 1966) DVD.

As the philosopher of cognition Elizabeth Camp has described, “Cartographic systems are a little like pictures and a little like sentences. Like pictures, maps represent by exploiting isomorphisms between the physical properties of vehicle and content. But maps abstract away from much of the detail that encumbers pictorial systems. Where pictures are isomorphic to their represented contents along multiple dimensions, maps only exploit an isomorphism of spatial structure- on most maps, distance in the vehicle corresponds, up to a scaling factor, to distance in the world.” Elizabeth Camp. “Thinking with Maps,” Philosophical Perspectives 21:1 (Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, 2007) 157–158.

Gérard Genette, Narrative Discourse, trans. Jane E. Lewin. (Cornell: Cornell University Press, 1980), 108.

George Barnett Johnston has described the introduction of principles of Scientific Management into the drafting room during this period through a close reading of Architectural Graphic Standards and debates within the journal of the drafting profession, Pencil Points. George Barnett Johnston. “The Division of Architectural Labor,” in George Barnett. Drafting Culture: A Social History Of Architectural Graphic Standards (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2008), 74–85. In the The Portfolio and the Diagram, Hyungmin Pai examines a wider array of architectural artifacts during the interwar period, including drawings, books, journals, manuals, specifications, and contracts in order to track the dissolution of the Beaux Arts system and the rise of a pluralist “discourse of the diagram” within American modernism. Hyungmin Pai, The Portfolio And The Diagram: Architecture, Discourse, And Modernity In America (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2002).

Describing the limit between established and inferred information in communication, Bateson writes: “Any aggregate of events or objects…shall be said to contain ‘redundancy’ or ‘pattern’ if the aggregate can be divided in any way by a ‘slash mark,’ such that an observer perceiving only what is on one side of the slash mark can guess, with better than random success, what is on the other side of the slash mark. We may say that what is on one side of the slash contains information or has meaning about what is on the other side.” While Bateson offers a series of non-graphic examples of this guesswork- the roots of a tree can be inferred from the tree above, the letter “h” or “r” or a vowel is likely to follow the letter “t” in the English language, the actions of the boss yesterday predict the actions today- these kinds of slash marks abound in architectural drawing as well. Gregory Bateson, Steps to an Ecology of Mind (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 1972) 130–131.

In the fully saturated page of working details, these represented parts are not merely fragments within a catalog; rather the break line tethers them into a chain of events - their sequence can be tracked around the perimeter of a room, across a façade, or along the length of a passageway. While this type of sequential movement seems to bear some relation to an “architectural promenade”—a hierarchical progression of views that one might experience while moving through a building—it is non-retinal, representing instead a collection of related orthographic vignettes that are visible only in the imaginary and regulated space of the measured drawing.

Works within this genre have recently been collected by Craig Dworkin in his study of post-war conceptual art and literature that is blank, erased, clear, or silent. Craig Dworkin, No Medium (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 2013).

Edwin Mather. Wyatt, Blue Print Reading; Interpreting Working Drawings (Milwaukee, WI: Bruce Pub. Co., 1920), 35. Mather’s “serious accidents” can be illustrated through Buster Keaton’s “One Week,” from 1920 and the animated Pink Panther film, “Pink Blueprint” from 1966, which both spoof the protocols of the construction site, and the accidents that inevitably ensue from errors in the drawing. More recently the slapstick genre of “Architecture Fail” images, circulating within online message boards and multipage slideshows reveal numerous examples of overly literal interpretations of drawing conventions. See, for instance, ➝.

Architecture and Representation is a project by Het Nieuwe Instituut, The Berlage, and e-flux Architecture.

Subject

Architecture and Representation is a collaboration between Het Nieuwe Instituut, The Berlage, and e-flux Architecture.