In 2017, I organized an event at the Mansion, a cultural space in Beirut’s Zoqaq el-Blat neighborhood, on the debates surrounding the future reconstruction of Syria.1 At the time, many architects and developers in Lebanon were looking at Syria’s reconstruction as a lucrative, exciting opportunity. They not only saw the rebuilding of Syria as a great chance for economic gain, but also believed that Lebanon’s decades of experience with reconstruction after the Lebanese Civil War and the 2006 attacks uniquely positioned Lebanese professionals to assist in Syria’s reconstruction. The purpose of the event was to critique this sense of certainty and to curb excessive enthusiasm: the Lebanese experience of reconstruction had, after all, been subject to criticism from both within and outside the country.2 Moreover, there were multiple threads connecting the two countries that would plague any involvement with questions about allegiances, hierarchies, and symbolic violence.3 But beyond all this, the contexts of war were different. The discussion among Lebanese and Syrian architects centered on the ethics of reconstruction, scrutinizing the implications of being involved in rebuilding another country.4 Already by that time, a robust array of Syrian architects were articulating visions and questions for the country’s urban reconstruction.

As destruction continues in Ukraine, communities and professionals in affected cities are already contemplating reconstruction. The number of initiatives, projects, and discussions, as well as actual processes of reconstruction currently occurring in the country, is impressive.5 Amidst these ongoing debates and reconstruction efforts, past experiences of rebuilding are continuously being invoked. There are comparisons being made not just with reconstruction precedents, but also with regard to the war itself. Reconstruction is indeed often linked to the type of war fought, the levels of destruction, the impact on cities, the morale and cultures of memory connected to it. Yet just a cursory look at the comparisons made with Ukraine today shows not only the benefits of comparisons, but also their limitations. A discussion on comparisons and “best practices,” as well as on the involvement of international actors in reconstruction, is therefore highly relevant at this time.

Learning from Comparisons

Invoking precedents and seeking comparisons means grappling with the perpetual tension between universalizing comparisons, which seek general rules, and individualizing comparisons, which emphasize differences between cases. Universalizing comparisons assist in the construction of overarching theories, pathways, and models, but face criticism for their tendency to overgeneralize and claim universality. In contrast, individualizing comparisons are rooted in more historical or ethnographic methodologies and focus on unique contexts, with criticism aimed at their low transferability.6 The question, then, is what kind of comparisons, models, and precedents can help the planning and implementation of reconstruction.

One important aspect to consider is who is making the comparison, and how. On the one hand, comparisons can be made in urban research. Stemming from a post-colonial drive to generate urban theory away from the usual suspects of Western musings, a school of comparative urbanism has brought comparisons between cities to the forefront of urban geography over the past decade.7 Comparative urbanism discusses contemporary cities under the lens of various processes. Comparing reconstruction efforts, then, not only makes comparisons between cities, but also between processes of rebuilding at different scales and involving different actors. While some comparative reconstruction work tries to derive standards models for reconstruction, other work seeks divergences between cities that had similar historical trajectories and urban profiles before war.8 Such comparisons of divergences, whether seeking variations in trajectories or encompassing variations among related cities, serve as analytical tools to learn about reconstruction post-factum.9

On the other hand, when comparisons are used to make decisions and implement action, normative thinking asks for a different type of caution. Both types of comparisons can be useful tools. Universalizing comparisons can highlight common patterns of events that occur. Using precedents also helps to highlight what has gone wrong and has backfired in other contexts. Challenges arise, however, when trying to derive pathways and “best practices” from universalizing comparisons and apply them to specific cases. In this case, divergent, individualizing comparisons can highlight contextual distinctions and serve as both a tempering tool of universal recipes and as a catalyst, coaxing us to consider context and unleash reflexive creativity. The role of comparisons, then, is to act as sentinels, cautioning against the uncritical adoption of models while encouraging adaptability, transformation, and creativity.

Reconstruction Beyond Metonymy

Discussions about the reconstruction of Ukraine are awash with historical antecedents and analogies. Yet the very notion of reconstruction has often been used in the last decades as an umbrella term for many things, including as a proxy for peacebuilding, stabilization, economic recovery, and institutional remaking. In both academic treatises and donors’ forum-speak, post-war reconstruction has been referred to as an endeavor traversing the terrain of architecture, economics, and politics, comprising actions beyond the literal reconstruction of infrastructure and the built environment as diverse as reconfiguring institutions, peacebuilding, stimulating job growth, and heralding development. Rebuilding cities, then, is one single component of a complex process. Rebuilding Libya or Iraq was more a project of state formation and so-called peacebuilding than planning for a careful rebuilding of cities. Yet in the case of Ukraine, discussions about reconstruction tend to be focused on the actual rebuilding of a destroyed materiality, which is key to economic recovery.

Discussions about Ukraine, as opposed to those about Bosnia and Herzegovina, Afghanistan, Iraq, Libya, or much of post-1945 Europe, start with an assumption of the political and economic continuity of the Ukrainian state. If the state itself is not in need of reconstruction, then focus shifts onto the built environment and infrastructure. Reconstruction in Ukraine is thus somehow freed of all the metonymical discussions of reconstruction as a political and economic process. Infrastructure here is literally infrastructure, yet there is also talk of renewed, revamped, and streamlined institutions. Central to this particularity is the nature of the conflict itself: a democracy was invaded by its neighboring country, a bully with imperial desires. Ukraine is a democracy that needs to be protected and will be rebuilt as such.

The reconstruction of Warsaw’s Old Town after 1945 went against the grain. Reconstruction approaches reflect an intersection of factors, from destruction degree to financial possibilities, from architectural and planning paradigms to cultures of memory related to the nature of aggression. Photo: Gruia Badescu, 2018.

Diverging Factors

One dominant media trope surrounding the reconstruction of Ukraine is a new Marshall Plan, referring to the reconstruction of (Western) Europe after the Second World War. This is also connected to the frequent, yet utterly incorrect, remark that the war in Ukraine is the first on European soil since 1945. While comparisons with the Marshall Plan are indeed relevant in terms of a call for the international community to fund reconstruction, they are less reflective of the way that funds were actually distributed and used back then. Marshall Plan money was used in West Germany for upgrading infrastructure and reconstructing industry, but not rebuilding cities, while in the UK it went to the colonial police. Moreover, Marshall Plan aid accounted for just 2% of the recipient countries’ GDP, while the value of destruction in Ukraine by mid-2023 was already multiple times the country’s entire GDP. Furthermore, when the Marshall Plan was invoked in the most recent conference on rebuilding Ukraine in June 2023 in London, it was primarily in the context of luring private investors from afar, rather than state aid to the Ukrainian government so that it could decide its own priorities, as happened in the emerging welfare states of Western Europe after the Second World War.10 Drawing comparisons with post-1945 reconstructions would necessitate examining the central role of the state in coordinating reconstruction in both Eastern and Western contexts. Furthermore, it would underscore the impact of differing political economies that could potentially challenge the prevailing neoliberal status quo in Ukraine.

The post-Second World War rebuilding of cities like Warsaw and London is also often brought up, yet those cities were metropolises that stood colossal in size and populace compared to places like Irpin or Bucha, or the fragments of larger cities attacked in the last year. Larger devastated cities in the East and South, like Mariupol, are for now under Russian control and are a traumatic sore spot in talk about reconstruction, with their exiled populations and trapped locals who now receive memorabilia from the Russian government to persuade loyalty under occupation. Places far from Russian positions, from Ismail on the Danube to Lviv in the West, have been bombed. As such, the scale of destruction is generally patchy within cities, yet encompasses the entire national territory, and is more severe in areas closer to Russia.

Rebuilding after Second World War aerial bombings occurred also in a distinct epoch for architecture and planning. Both the modernist ethos and the socialist-realist vision of palaces for workers aimed to completely reshape urban form. Destruction was seen as an opportunity. A car-centered urban model, alongside enthusiasm for the new and the erasure of the old, eventually led to reconstruction being called a “second destruction” by the West German left, resulting in inhospitable cities.11 As such, contemporary paradigms like the smart city need to be critically examined before being enthusiastically embraced within the framework of reconstruction. While the period after 1945 was greeted with modernist certainty, the contemporary era is marked by the disruptions and frictions of the postmodern dérive and a rhizome of features, including starchitects, city competitions, and weakened planning aims.12 City-making has largely been privatized and orchestrated by developers.13

In Ukraine itself, there is one vision of the future: Europe. However, the form and shape of this future for cities remains uncertain. Simultaneously, there is a deep connection to the past—to national identity, heritage, memory—that is integral to our contemporary age and its turn towards memory and heritage since the 1980s. Rebuilding cities today operates in a different framework than before. While memorialization after the Second World War was centered on heroes and resistance, a new focus on victimhood has reshaped memorial architecture. After 1945, the meaning of heritage was restrictive, and reconstructing buildings the same way they were before war was a professional “no-go” area. In the 1980s, however, the restoration of Warsaw’s old town, which was erased by the Nazis, was recognized as a UNESCO World Heritage site. The International Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS) is currently writing new documents on reconstruction that embrace a thoughtful restoration after traumatic events. Yet the question of which pasts to incorporate necessarily arises. In the aftermath of the war in Ukraine, Soviet Modernist heritage can be either embraced as Ukrainian or vilified as foreign.14

Mapping the social perception of war is essential to understanding the framing of future reconstruction, particularly in the Donbas. The different experiences of war within Ukraine will have significant implications for reconstruction of both the built environment and the social fabric. In this regard, insights from the recent Yugoslav wars and reconstructions are worth contemplating.15 As such, the reconstruction of larger cities will have to adapt to the displaced people who will prefer to stay there after the war, while reconstruction in the separatist and occupied territories needs to grapple with evolving narratives and allegiances.16

The rebuilding of Ukraine is thus underpinned by a distinct ethos from previous reconstructions. There are, however, a series of insights that can be drawn from comparisons, which might be helpful in thinking about Ukraine’s reconstruction. From opportunities to possible pitfalls, precedents can serve both as horizons of intervention and cautionary tales to spark critical engagement.

Coventry´s reconstruction planning under Chief Architect Donald Gibson began right after the Blitz, and it was actually even influenced by Gibson’s ideas of urban redevelopment before the war. War was seen as an opportunity by many modernist planners and architects at the time. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Reconstruction as a continuous process

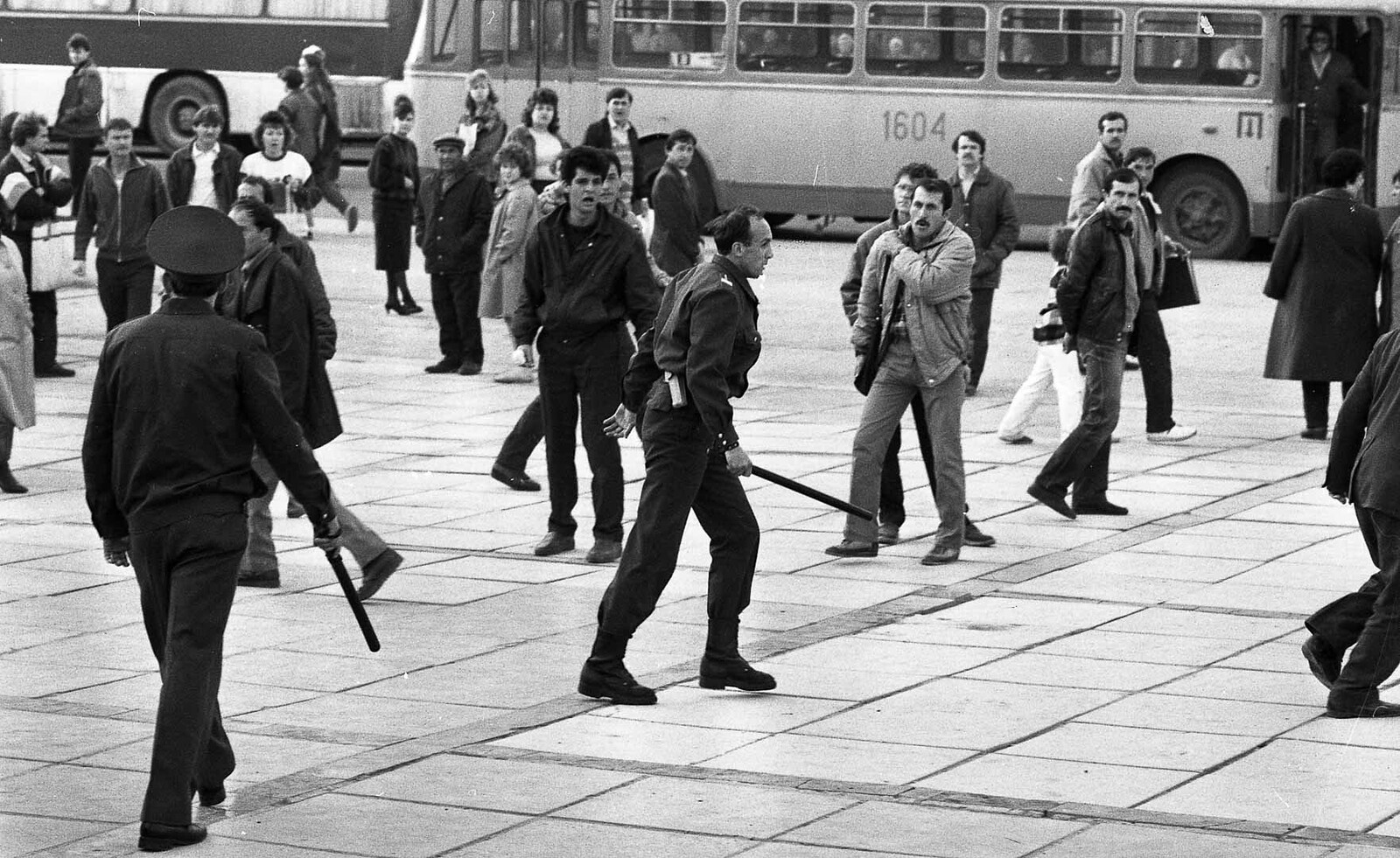

Reconstruction often commences while destruction is still ongoing. As bombs were shattering cities in Britain and Germany, planners and architects were already at work redesigning them. In Beirut, in 1982, seven years into the Lebanese Civil War and with a still unclear horizon, a workshop took place where Polish and German architects discussed reconstruction best practices and the lessons learned from the mistakes of post-1945 rebuilding efforts. In the besieged city of Sarajevo during the 1990s, architects braved sniper fire to cross the city and meet at the architecture faculty to discuss future reconstruction. This was not only a way to contemplate the future, but also to maintain a sense of normalcy and mental resilience amidst the siege. Nevertheless, thinking about reconstruction during the Second World War and in Sarajevo were firmly grounded in the locale and existing urban paradigms and aspirations. In contrast, Beirut workshops evoked learning from elsewhere, thinking of precedents and examples that can inspire.

The highly designed public spaces of Beirut´s rebuilt central business district might have showed an interest from the team of international architects in recreating a heritage space of the fabled Paris of the Middle East, but the process actually entailed the destruction of actual heritage to rebuild anew, the dispossession of owners and a top-down process that silenced community voices. It led to a manicured space that was worlds apart from the vibrancy of pre-war times. As a Beirut woman whose uncle had a shop in the old center said, it became sleek, unrecognizable, it lost its soul. Photo: Gruia Badescu, 2018.

Reconstruction can serve as an act of erasure of the unwanted, abjectified building types and styles, which may no longer harmonize with the imaginary of the post-war country. In the former Yugoslavia, or post-2008 Georgia, socialist modernist buildings were often the target of removal or makeover. Socialist landmark Sarajka in Sarajevo (left), for instance, which was damaged in the 1990s, was rebuilt as the BBI Centar (right). Source: SARAJEVO.Co.Ba (left), Gruia Badescu, 2013 (right).

Reconstruction can serve as an act of erasure of the unwanted, abjectified building types and styles, which may no longer harmonize with the imaginary of the post-war country. In the former Yugoslavia, or post-2008 Georgia, socialist modernist buildings were often the target of removal or makeover. Socialist landmark Sarajka in Sarajevo (left), for instance, which was damaged in the 1990s, was rebuilt as the BBI Centar (right). Source: SARAJEVO.Co.Ba (left), Gruia Badescu, 2013 (right).

In Mostar, as minarets were rebuilt, the Catholic church also had its tower reconstructed, but seven times higher than before, showcasing antagonism and frictions in the cityscape, a competition that accounts to a symbolic violence and a continuation of conflict with other means. In addition, a cross was placed on the mountain above the city to tower over the Muslim and Christian city. Photo: Gruia Badescu 2009.

The highly designed public spaces of Beirut´s rebuilt central business district might have showed an interest from the team of international architects in recreating a heritage space of the fabled Paris of the Middle East, but the process actually entailed the destruction of actual heritage to rebuild anew, the dispossession of owners and a top-down process that silenced community voices. It led to a manicured space that was worlds apart from the vibrancy of pre-war times. As a Beirut woman whose uncle had a shop in the old center said, it became sleek, unrecognizable, it lost its soul. Photo: Gruia Badescu, 2018.

Reconstruction as violence

Reconstruction itself can be violent.17 The 1960s criticism of West German reconstruction as a “second destruction” is by no means singular. From Coventry to Rotterdam to Minsk, many cities were rebuilt after the Second World War while erasing traces of the past. In Beirut, reconstruction by Solidere after 1990 involved demolishing still-standing buildings in order to rebuild the city center as a “heritage” site, which resulted in an exclusionary space of high-end stores, restaurants, and a lack of social diversity.18 In the former Yugoslavia, the erasure of modernist landmarks and their replacement with new structures was linked to the sometimes-intentional erasure of the republic’s overt presence in urban space.19 Moreover, reconstruction in ethnically contested spaces often involves a competition for territory, where markers of identity, such as religious buildings, define and appropriate urban space. In Bosnia and Herzegovina, for example, a competition between new structures, including the height of minarets and towers, showed the antagonistic character of otherwise ordinary buildings.20

Ravaged by the Yugoslav army in 1991, Vukovar has since evolved into a living memorial in Croatia—a poignant testament to the homeland war, as articulated by the Croats. Vukovar’s reconstruction shows how reconstruction and memorialization continue conflict through other means into what Britt Baillie calls a prolonged “conflict-time.” It was rebuilt as a martyred city, focusing on ruin-memorials—particularly the Water Tower—and plaques, and refusing to use Cyrillic—seen as a marker for Serbian language—on street names despite the presence of a significant Serbian minority. Source: Wikimedia Commons, Sokac121.

In Belgrade, ruins of 1999 NATO bombing like the General Staff of the Yugoslav Army still stand more than twenty years after. They serve as mnemonic objects, reminiscent of destruction and supporting a narrative of victimization, as well as a material background for receiving Vladimir Putin as a guest of honor in 2014. Photo: Gruia Badescu, 2013.

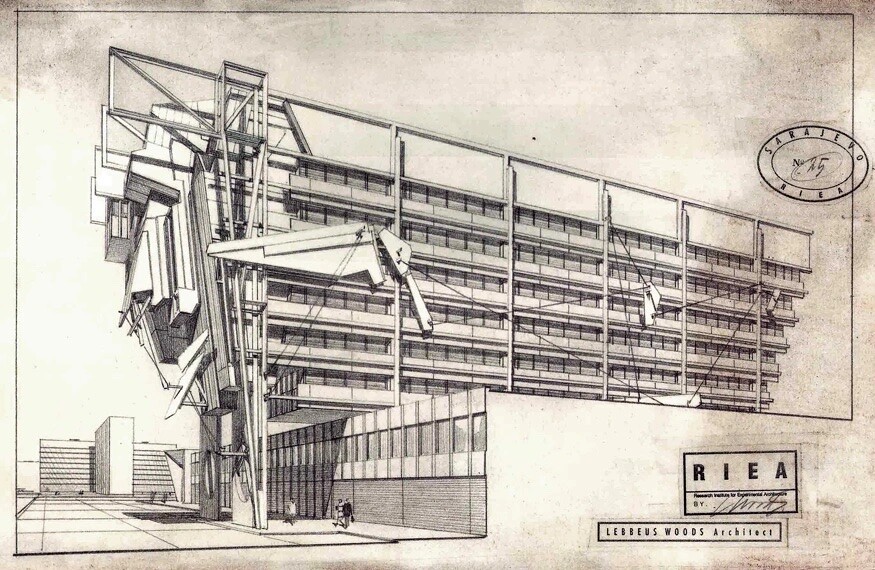

Lebbeus Woods, Elektroprivreda, Sarajevo, 1994. Lebbeus Woods visited Sarajevo after the war and proposed reconstructing the city’s buildings according to a double structure logic that he termed, “radical reconstruction.” One part, the majority of the building, would be reused for various functions, while a small part would be transformed in a structure that he called a “scab,” which symbolizes the unhealed wounds of war. The intention was to perpetually invite contemplation on the impact and significance of war and to embed ruination in the cityscape. Source: LEBBEUS WOODS (blog).

Sarajevo wanted to create a memorial in the way that cities like Berlin have their ruin-memorials to war. The building that was the object of the discussion, the Oslobođenje newspaper building, was a symbol of resistance and resilience. Journalists worked there throughout the war in the most difficult of conditions, reported from under sniper fire, and published on increasingly thinner paper. Nevertheless, the building was rebuilt with a glass façade after it was bought by the owner of a new daily, the Dnevni Avaz. Its memorial potential was thus erased. Source: Wikimedia Commons, Hedwig Klawuttke.

Ravaged by the Yugoslav army in 1991, Vukovar has since evolved into a living memorial in Croatia—a poignant testament to the homeland war, as articulated by the Croats. Vukovar’s reconstruction shows how reconstruction and memorialization continue conflict through other means into what Britt Baillie calls a prolonged “conflict-time.” It was rebuilt as a martyred city, focusing on ruin-memorials—particularly the Water Tower—and plaques, and refusing to use Cyrillic—seen as a marker for Serbian language—on street names despite the presence of a significant Serbian minority. Source: Wikimedia Commons, Sokac121.

Reconstruction as healing

Reconstruction is not merely about restoring physical structures; it entails working through a traumatic past, healing, as well as envisioning a future beyond the scars of war. The process is an intricate interplay of recovery, reconciliation, and resistance. Yet meanings and interpretations of reconstruction and memorialization are always situated in context. There is no singular pathway in dealing with the past, and a memorial practice that has a function in one place might work completely differently somewhere else. In the case of Belgrade, for instance, several ruins of the 1999 NATO bombing still stand more than twenty years after, often in prominent locations in the city center. These ruins serve as mnemonic objects, but their presence in the city can also perpetuate a sense of continuous victimization and disgruntlement with the West.21 In neighboring Bosnia and Herzegovina, however, Lebbeus Woods proposed reconstructing Sarajevo’s buildings with “scabs” to symbolize the unhealed wounds of war, but the reaction in Sarajevo was largely one of rejection, as people did not want to live with a reminder of the city’s long, violent, and dehumanizing siege. In fact, the idea of designating a ruin as a memorial in Sarajevo only emerged after a significant portion of the reconstruction had already taken place.

In Mostar, a city with an uneasy post-war cohabitation of Bosniaks and Bosnian Croats, the World Bank has invested in the reconstruction of the Ottoman era bridge, seen as a flagship project for reconstruction and reconciliation, while the Bulevar remained destroyed for decades to come. Photos: Gruia Badescu, 2009.

In Mostar, a city with an uneasy post-war cohabitation of Bosniaks and Bosnian Croats, the World Bank has invested in the reconstruction of the Ottoman era bridge, seen as a flagship project for reconstruction and reconciliation, while the Bulevar remained destroyed for decades to come. Photos: Gruia Badescu, 2009.

The National Library/old City Hall in Sarajevo was rebuilt slowly, with a large part of funds coming from Austria, the former imperial power which built it, and the EU. The EU had exhibited significant reluctance to take action during the war, and their response was primarily limited to deploying peacekeeping forces. Subsequently, there was a prevailing sense of guilt, which prompted a surge in attention and financial resources directed towards numerous reconstruction projects. Photo: Gruia Badescu, 2014.

In Mostar, a city with an uneasy post-war cohabitation of Bosniaks and Bosnian Croats, the World Bank has invested in the reconstruction of the Ottoman era bridge, seen as a flagship project for reconstruction and reconciliation, while the Bulevar remained destroyed for decades to come. Photos: Gruia Badescu, 2009.

Reconstruction as international arena

International actors have increasingly become involved in the reconstruction processes.22 In Bosnia and Herzegovina, international organizations and foreign powers descended with their visions, strategies, and well-intentioned schemes, yet with scant consideration for local desires and perceptions. The World Bank invested in the reconstruction of the Ottoman bridge in Mostar, seen as a flagship project for reconstruction and reconciliation. Nevertheless, the focus on the bridge and its symbolic potential has led to the neglect of other heritage buildings that served important social functions, such as those along the city’s destroyed Bulevar.23 In Sarajevo, the Saudis expressed interest in participating in reconstruction through the lens of Islamic solidarity. But their rebuilding of the Gazi Husrev mosque occurred without proper consultation and involved whitewashing walls previously adorned with typical Balkan florid drawings.24 Similarly, Iran’s involvement in the reconstruction of Lebanon after the 2006 war is a marker of political influence and thus support for Hezbollah. International reconstruction efforts occur for many reasons, from solidarity to guilt, from post-imperial gazes to memory politics.25

The process by which international actors contribute to reconstruction efforts can also vary widely and be of great importance in determining their outcomes. In Mostar, a specialized unit was created to introduce a streamlined procedure that would ensure swift progress and the engagement of various local stakeholders. The EU involvement in Sarajevo, however, was associated with a highly bureaucratic procedure that took a long time to approve funds. Moreover, local authorities used a more ad-hoc matching of international funds to specific building projects.

Beyond states and international organizations, international architects and designers increasingly feature in reconstruction planning. Despite being well-intentioned and bringing expertise and resources, their lack of contextual knowledge can lead to detrimental outcomes. They may, for instance, impose preconceived ideas and solutions that do not align with the needs and aspirations of the local community. The perils of parachute-in urbanism include the perpetuation of power imbalances, cultural insensitivity, the erosion of local identity, and the exclusion of marginalized groups. To avoid these perils, it is crucial for architects, either international or domestic, to prioritize collaborative approaches that empower local communities, respect their agency, and foster inclusive design processes. These collaborations necessitate context-sensitive considerations, including mapping social fabrics, understanding narratives of war, acknowledging the varied meanings attributed to ruins, and capturing needs and visions for the future.

Conclusion

Reconstruction is an endeavor that bridges physicality, memory, and imaginaries of the future. To navigate its complexities and intricacies, context is the compass. The narratives of war, the scars of conflict, and the essence of loss are threads that must be woven into the very fabric of reconstruction. Architectural and planning decisions need to be supported by an anthropological lens. The nuances of the past, the nature of destruction, and the echoes of memory all mold the contours of urban rebirth. Working without proper knowledge of the local conditions, relying solely on simplistic comparisons, or applying universal models can have unintended negative consequences. Furthermore, every intervention or change, even if initially intended to be temporary, carries lasting effects.

Differentiating comparisons can be used to temper enthusiasm about best practices. The value of universalizing comparisons lies in highlighting what can go wrong—what should be avoided, rather than what should be followed. Identifying places that have witnessed similar processes can help indicate possible trajectories while mediating differences. The key challenge remains who makes these comparisons and what is their role in the rebuilding of Ukraine. International interventions, notwithstanding their intentionality, can backfire. Strengthening the voice of the local actors and seeing reconstruction as a collaborative endeavor, one that uses comparison as a resource but develops a multilateral vision through participation across scales, is key. The ethics of reconstruction, from Beirut to Mariupol, need to be at the forefront of this discussion.

The timing was before the near breakdown of the Lebanese state from 2019 on, with the debilitating banking crisis, huge protests, shocking explosion, and failure of infrastructure that brought the country to an impasse.

To just give a few examples, Marwan Ghandour and Mona Fawaz, “Spatial Erasure: Reconstruction Projects in Beirut,” ArteEast Quarterly, Spring 2010; Howayda Al-Harithy and Dina Mneimneh, “The {Framing} of Heritage in the Post-War Reconstruction of Beirut Central District (Lebanon),” in Urban Recovery: Intersecting Displacement with Post War Reconstruction, ed. Howayda Al-Harithy (Abingdon: Routledge, 2021), 239–70; Aseel Sawalha, Reconstructing Beirut: Memory and Space in a Postwar Arab City (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2010); Craig Larkin, “Remaking Beirut: Contesting Memory, Space, and the Urban Imaginary of Lebanese Youth,” City & Community 9, no. 4 (2010): 414–42.

The background consists of a complex web of historical events, symbolic hierarchies in the region, and memories of the Syrian occupation in Lebanon, as well as the presence of Syrian refugees in Lebanon and Lebanese debates about identity and their role in the Arab region.

The relationship between architectural post-war reconstruction and the ethics of dealing with a difficult past was the topic of my PhD dissertation at the University of Cambridge, defended in 2018, and expanded into a forthcoming book.

Ievgeniia Dulko, Fulbright scholar in planning at the University of Illinois, wrote an MA dissertation mapping the extent of such initiatives.

See, for instance, comparative research by American sociologist Charles Tilly. He distinguished between four modes of comparison. Individualizing comparisons serve to highlight the particularities of a given case. In contrast, generalizing comparisons capture recurrent structures and processes across cases. Variation-finding comparisons aim to causally explain difference across cases. Encompassing comparisons treat cases as embedded in a shared social environment.

Jennifer Robinson, Ordinary Cities: Between Modernity and Development (Abingdon: Routledge, 2006); Colin McFarlane and Jennifer Robinson, “Introduction—Experiments in Comparative Urbanism,” Urban Geography 33, no. 6 (2012): 765–73.

Beirut and Sarajevo, for instance, both share an Ottoman past, an imperial makeover (French and Habsburg, respectively), modernization under Yugoslavia and independent Lebanon, then war destruction and rebuilding. They share a mix of religiously diverse populations that speak mutually intelligible languages. Nevertheless, the two cities, following wars in the late twentieth century, experienced very distinctive reconstruction processes and concepts, which can be attributed to the influence of local agency and contextual idiosyncrasies. See Gruia Bădescu, “Post-War Reconstruction in Contested Cities: Comparing Urban Outcomes in Sarajevo and Beirut,” in Urban Geopolitics: Rethinking Planning in Contested Cities, ed. Camillo Boano and Jonathan Rokem (Abingdon: Routledge, 2017), 17–31; Gruia Bădescu, “Traces of Empire: Architectural Heritage, Imperial Memory and Post-War Reconstruction in Sarajevo and Beirut,” History and Anthropology 30, no. 4 (2019): 1–16; Gruia Bădescu, “Cosmopolitan Heritage?: Post-War Reconstruction and Urban Imaginaries in Sarajevo and Beirut,” in Controversial Heritage and Divided Memories from the Nineteenth Through the Twentieth Centuries, ed. Marco Folin and Heleni Porfyriou (Abingdon: Routledge, 2020), 121–38.

Tilly defines an encompassing comparison as the act of comparing cases that are connected by belonging to the same larger social structure, or by relationships of dependency. For instance, comparing reconstruction between Kyiv and Bucha will not only have to consider differences of size, economic power, and level of destruction, but also the territorial relationships between the two and the fact that Bucha belongs to the Kyiv Oblast.

While the existence of various pre-invasion initiatives in Ukraine by international organizations has already established frameworks for absorbing financial resources, it is unclear how these organizations will deal with the exacerbated scale of destruction. The creation of agencies dealing with the Marshall Plan aid could be a valuable precedent to discuss more.

A. Mitscherlich, The Inhospitality of Our Cities (Frankfurt: Suhrkamp, 1965).

The Ukrainian government has even controversially announced a dissolution of planning mechanisms and the requirement of architecture stamps, suggesting that many architects are either fighting at the front or have fled the country.

Despite these trends, in the post-socialist, post-war Yugoslav space, I found instances of resistance and rebellion, of idiosyncrasies and independence in style, and of resilient agency in architecture. In Sarajevo, architects like Amir Vuk Zec disrupted office architecture models and opted instead for a syncretic place-making that blends Sarajevo´s diverse influences and shows no compromise. For more, see Gruia Badescu, “The City as a World in Common: Syncretic Place-Making as a Spatial Approach to Peace,” Journal of Intervention and Statebuilding 16, no. 5 (2022): 600-618.

The debate about Ukrainian Soviet-era architecture was already vibrant even before the war, see, for instance, the impassionate work of people like Ievgeniia Gubkina.

Insights from the war in Bosnia and Herzegovina show that internally displaced people often tend to stay in large cities when conflict ends, as they have better opportunities for jobs and livelihoods, despite the loss of their original home. See Stef Jansen and Staffan Löfving, Struggles for Home: Violence, Hope and the Movement of People (New York: Berghahn Books, 2009); Gruia Bădescu, “Dwelling in the Post-War City Urban Reconstruction and Home-Making in Sarajevo,” Revue d’études Comparatives Est-Ouest 46, no. 04 (2015): 35–60.

Reflecting on the experience of the war in Bosnia and Herzegovina, we can discern how, over time, people who were once neighbors become estranged, constructing separate identities and nurturing distrust. Anthropologist Ivana Macek traces the transformation of perceptions by people who initially coexisted in harmony, but as time unfolded, began constructing separate identities and cultivating cautious and ambivalent emotions—a lack of confidence, distrust—towards those they increasingly perceived as belonging to a different group. Macek’s work is a testament to the profound changes that can occur in the crucible of conflict, where the shared fabric of community can unravel, leaving in its wake a tapestry woven with threads of division and suspicion. This opens the question of what is actually happening today in Ukraine’s occupied territories, and particularly in Donbas, with its longer Russian presence. To what extent identities have been reshaped by war and Putin’s propaganda is yet unclear, as are what tensions and frictions might emerge between people with different allegiances, radicalized by war, once the country is reunited.

This violence can manifest in multiple forms, including destruction through reconstruction, symbolic violence, cultural violence, and the showcasing of structural violence. See Dacia Viejo-Rose, Reconstructing Spain: Cultural Heritage and Memory after Civil War (Brighton: Sussex Academic Press, 2011); Gruia Bădescu, “Urban Memory After War: Ruins and Reconstructions in Post- Yugoslav Cities,” in Contested Urban Spaces: Monuments, Traces, and Decentered Memories, ed. Ulrike Capdepón and Sarah Dornhof (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2021).

Gruia Bădescu, “Beyond the Green Line: Sustainability and Beirut’s Post-War Reconstruction,” Development 54, no. 3 (2011): 358–67.

Gruia Bădescu, “The Modernist Abject: Ruins of Socialism, Reconstruction, and Populist Politics in Belgrade and Sarajevo,” in Memory and Populist Politics in Southeastern Europe, ed. Jody Jensen (Abingdon: Routledge, 2021), 27–46.

Robert Bevan, The Destruction of Memory: Architecture at War (Reaktion Books, 2007); Robert M. Hayden, “Intersecting Religioscapes and Antagonistic Tolerance: Trajectories of Competition and Sharing of Religious Spaces in the Balkans,” Space and Polity 17, no. 3 (2013): 320–34; Gruia Bădescu, “Between Repair, Humiliation, and Identity Politics: Religious Buildings and Memorials in Post-War Sarajevo,” Journal of Religion & Society 21 (2019): 19-37.

See Gruia Bădescu, “Urban Geopolitics in’Ordinary’and’Contested’Cities: Perspectives from the European South-East,” Geopolitics 28, no. 5 (2022): 1–26.

According to Iryna Matsevko, historian and deputy vice chancellor at the Kharkiv School of Architecture, the reconstruction of the Balkans is a poignant precedent for Ukraine exactly from this perspective of international involvement. Linda Kinstler, “Architect Plan a City for the Future in Ukraine, While Bombs Still Fall,” New York Times, November 7, 2022, ➝.

For many of the Mostar Croats, the bridge was seen as a mere connection between the Muslim sections of the city and as a piece of Ottoman heritage, thus not the unifier that it was portrayed to be. Jon Calame and Amir Pasic, “Post-Conflict Reconstruction in Mostar: Cart before the Horse,” Divided Cities/Contested States Working Paper 7 (2009).

Bevan, The Destruction of Memory.

See Badescu, “Remaking the urban: International actors and the post-war reconstruction of cities” (forthcoming).

Reconstruction is a project by e-flux Architecture drawing from and elaborating on Ukrainian Hardcore: Learning from the Grassroots, the eighth annual Construction festival held in the Dnipro Center for Contemporary Culture on November 10–12, 2023 (2024), and “The Reconstruction of Ukraine: Ruination, Representation, Solidarity,” a symposium held on September 9–11, 2022 organized by Sofia Dyak, Marta Kuzma, and Michał Murawski, which brought together the Center for Urban History, Lviv; Center for Urban Studies, Kyiv; Kyiv National University of Construction and Architecture; Re-Start Ukraine; University College London; Urban Forms Center, Kharkiv; Yale University; and Visual Culture Research Center, Kyiv (2023).