Ievgeniia Gubkina and Ammar Azzouz are both architects, writers, scholars, and educators. They have both been forced to flee their home cities, Homs and Kharkiv: large, historic cities, brutally disfigured by brutal twenty-first century wars. They also both recently published books about the destruction of their cities: Domicide: Architecture, War and the Destruction of Home in Syria, by Ammar Azzouz, was published by Bloomsbury in 2023, and both Being a Ukrainian Architect During Wartimeand Kharkiv: Architectural Guide, by Ievgeniia Gubkina, were published by DOM in 2023. This interview sees Gubkina and Azzouz come together to discuss their new books and converse about solidarity, emotion, and writing; about war and its representation; about the perils and (im)possibility of return; about ordinary versus monumental heritage; about anger, grief, and justice; and about the pitfalls and perfidies of a reconstruction process disconnected from the needs, interests and voices of ordinary people.

Ammar Azzouz: I have always had a solidarity for Ukraine and Ukrainians, but your book took me to a different level of understanding. One of these reasons for this is your emphasis on the link between architecture and emotions. That link is very often lost in conversations about wars and cities. You mentioned in one chapter that someone said at a conference that Ukrainians should only be invited after a few years, once their emotions have settled down. As a Syrian, I find that very painful to hear. I often hear comments like “you’re writing too personally about architecture,” or “you bring too much of yourself to the conversation, and in academia we don’t do that.” But architecture is not walls and stones, it’s the people. The way you deal with trauma is not to repress it or escape from it, but to tell stories, which, as you say, can be done through architecture. You were writing when so much was being lost: people, cities, history, memory. Is writing a way for you to deal with the loss of Kharkiv?

Ievgeniia Gubkina: Allowing myself to talk personally is something that’s helped me a lot during wartime. I’ve had to lean on these emotions, on the belief that it’s okay to feel all these things. It’s really difficult to allow yourself to go through such a traumatic experience and try to understand, to feel everything. At the same time, I just decided not to doubt myself. I decided that it is okay to talk openly, in universities, about all the things that people would otherwise be silent about. I decided to become blind to what people think of me. I’ve paid such a big price, so I feel like it’s okay for people to hear all this information. It’s not about them! In my book, I called architecture a “transitional object,” or something that eases the anxiety of separation.1 But now I feel that, for many people, I myself am becoming a transitional object. Do you feel like that is a kind of sacrifice?

AA: It’s a huge responsibility. I would be afraid to fail my city and fail my people. I also don’t want to act as a microphone. As someone who lives in the comfort of London, I wish that the people of Homs could speak for themselves. But at the same time, I see that those who are still there have very few resources to do so and peoples’ lives would be at threat if they speak even if they did. I write as a way to tell the story of my city, but it’s one voice among many. At the same time, I see how the story of my city is fading away, and how the city itself is becoming forgotten, with what the news media calls “war fatigue.” Writing is a way for me to resist that forgetfulness, to try and keep the memory alive. And, as you say in your book, to let history be told by the victims, which always tells a different story, one that is closer to the pain of the people. You mentioned in your book a sense of guilt for leaving, or a sense of responsibility or desire to return. How do you feel about returning to Kharkiv?

IG: I’m “privileged” in the sense that I have a choice whether to return or not. This summer I had the opportunity, but I decided that I’m not mentally ready yet. The city is not the same as it used to be. It’s not as destroyed as Mariupol, for example. Kharkiv is more “lucky.” But on the other hand, it is much more damaged than Lviv or the western part of Ukraine, since Kharkiv is a front-line city and the risk of being captured has not gone away. There is a big difference in the geography of the country at war and the levels of trauma that have been experienced, for example, between refugees from Mykolaiv or Mariupol and those from Lviv. Kharkiv is partially destroyed. It’s still under shelling. Despite this, a lot of my friends and relatives decided to return. One thing you and I share is a love for our cities. The relationship I have with it, however… It doesn’t feel like we’ve broken up, but more like it’s dead, which leaves me in a process of grieving. It feels as if the city is my grandfather, who is in intensive care and that I have to say goodbye to. If I went back there this summer, it would have only been to say goodbye. Maybe I decided not to go just because I don’t want to say goodbye.

Homs, 2022. Photo: Anonymous.

AA: People often talk about the right to return, but what about the condition of not being able to return, even to the ruins of their homes? Sadly, in Syria, it’s almost impossible for most people who have been displaced to return. But as you said, this is not just about a legal or political situation, but also practically: they don’t exist any longer. When we hear about the thousands of buildings destroyed in Ukraine, or Syria, we don’t hear about the place-attachment and the memory that people lost with them. When thinking about reconstruction, there’s a tendency in many international organizations to think about big monuments and big symbolic places, like Kharkiv’s Freedom Square. UNESCO or other organizations will be interested in certain historic places—palaces, monuments, bridges—but most damage is actually done to residential buildings. There is a tension in reconstruction between housing and heritage.

IG: Yes, you’re right. Cities are not their main squares or great heritage sites recognized because of their cultural value. International organizations’ concept of heritage is very superficial. People live in ordinary neighborhoods! Ukraine has an enormous amount of mass housing. These huge residential prefabricated panel multi-storey buildings are networks of people. Damaged buildings are evidence of a kind of violence done against people. We need to shift focus away from a naive understanding of heritage as “significant objects” and move it towards dwelling and people’s everyday routine. I remember seeing a documentary by Deutsche Welle of a woman revisiting Saltivka, the most populated (and most destroyed) neighborhood in Kharkiv, after fleeing to Germany. She returns to the prefabricated panel building where she lived before the war, and when she got there, the woman just cried, and cried, and cried. To me, this is evidence of heritage. I spent years promoting the value of prefabricated panel buildings, explaining that these grey ugly buildings are the heritage of modernist architecture too. But now, after more than a year of war, I hope that their heritage value doesn’t still need to be advocated for. So many people have been made aware of what they mean to them. One of the things that struck me most about your book was its focus on the home, which is a really powerful concept but something that heritage institutions can somehow be really blind to.

AA: This is very true. Many of the conversations about reconstruction neglect the questions of rebuilding peoples’ homes. However, the idea of home extends beyond any individual’s physical house; it encompasses many different scales including the neighborhood, the city, the country, and even beyond in exile. Millions of Syrians are displaced from their country, and they are reconstructing their homes—a different type of home—through intangible heritage, through art, music, literature, and food. Home is a concept that speaks to different spaces and practices of belonging.

IG: I was really struck by the chapter in your book on reconstruction. Usually we have this assumption that reconstruction is something good, that it’s something for the people. But reconstruction can be another tool of erasure.

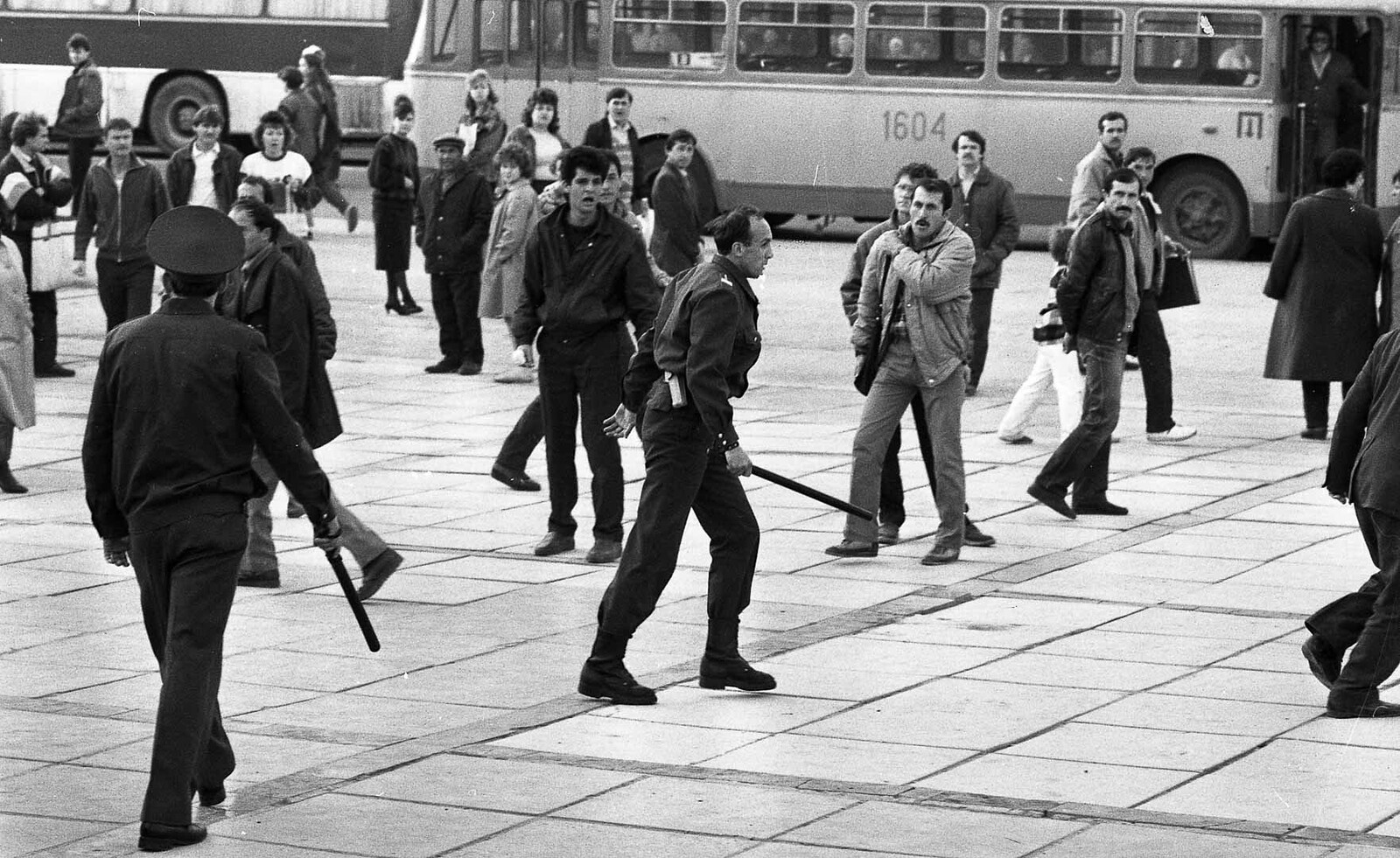

Women protesting in Homs on 31 of October 2011. Image was sent to Ammar Azzouz with a request to remain anonymous.

Martyr’s Memorial (to the right of the figures) built in late 2018. Photo: Anonymous, 2019.

Women protesting in Homs on 31 of October 2011. Image was sent to Ammar Azzouz with a request to remain anonymous.

AA: Reconstruction can bring with it more violence. A lot of times, sadly, reconstruction becomes an opportunity for governments, politicians, investors, and international companies to make profit. In southwest Damascus, for instance, new urban planning decrees were established during the war which enabled the destruction of peoples’ homes labeled “informal” or “illegal.”2 Residents were pushed out to lay foundations for luxury residential buildings. In Homs, even memory is being reconstructed by the government. At the heart of the city, where protests took place in 2011, a new monument was constructed for the “martyrs” of the Syrian Army. The choice of this monument’s location, and the time it was erected, was deliberate. The monument was built in late 2018, after the government ended the siege of rebel held areas and pushed them out of the city. With more than half of the city’s neighborhoods remained in ruins, it was a statement to the people of Homs: rather than creating a memorial for innocent civilians killed in the protests (or rebuilding people’s homes), the government sent a message of power and domination on the very site where the protests against them happened. Who decides what to remember and what to forget? Whose voice is heard in reconstruction? I found these questions explored eloquently in your work, when you say that those who own the narrative control the situation and make the choices. The people who own the narrative are often not the people who actually experienced them. International donors and governments are often the ones with the power to decide how things go. They might think that rebuilding a bridge, a church, or a mosque is the way to bring people together, but for impacted communities, another site might be better, like a library, a community center, a charity, or a school. Before the invasion, you did many walking tours of Kharkiv. Given this experience, I wonder how you think about remembering what’s happened? In my own experience of Homs, I feel like every site has history: on this site there was a protest; on another, there was a massacre; on another, an explosion; here, people were kidnapped. Despite all this information, however, I feel like we’re losing the story of what happened.

IG: Guests on my walking tours often used to be historians from abroad, who were mostly interested in what I would call difficult memory, in sites of the history of totalitarianism. It was traumatizing to develop these tours for these people, working with places of historical amnesia that people wanted to forget—sites of massacres, or places where people were tortured and killed. Kharkiv was the capital of Soviet Ukraine from 1919–1934, and it was quite a bloody place during times of Stalinist repression. So many buildings in the central part of the city are connected to some crime. Having dealt for so long with this “historical blood,” I guess I have some tools to deal with what’s happening today. These new crimes need to not only be documented, but also interpreted and narrated.

AA: In your book, different moments and sites of trauma and struggle are not only narrated through text, but also in photographs. What was your relationship with the photographers, who are still in Kharkiv and capturing these places?

IG: I worked quite extensively with photographers, especially Pavlo Dorohoi, who was in Kharkiv during the most difficult times, the hardest missile attacks. Sometimes he was at the site just a few minutes after the missile hit. It was quite dangerous. During the first weeks, nobody controlled these reporters, so they could make really significant photos. Pictures shape the narrative of war. But after months of working to document not only the destruction of buildings but human deaths on such a large scale, a lot of the photographers I have been working with are suffering from a kind of PTSD.

AA: There’s a certain image that I found striking and very painful to look at, which is of a street in ruins. There are no streetlights, but there are cables hanging in the sky. And between the ruins, there’s a woman walking with her suitcase. On her face you can see such a profound level of frustration, exhaustion, and fatigue. Photographs like this can brings to light the impact of the war on everyday people. They can tell us what war actually means.

MM: I’d like to speak about anger. Anger is something that comes and goes and is triggered by particular events. Jenia, you speak in your book about how your anger changes, and how you deal with it by going on a mission to destroy or defeat Russia through narrative. Ammar, how do you deal with the anger?

AA: Without justice, there will always be anger. In Syria today, it is not possible to publicly grieve. It is not possible to admit that civilians have been lost and grieve them in in the street, even in peaceful demonstration. There is no way for people to remember their loved ones but secretly. That sense of anger will always remain until there’s transitional justice, or there’s a way for people to come together to memorialize, remember, and grieve publicly. That’s why the durability and the voice of the Syrian diaspora is important. I wrote in my book that pain starts as a headline in the news and then turns into a footnote in history. It’s one of the saddest things for people to feel unseen and forgotten. Anger will remain until there’s a system or infrastructure of justice that allows people to feel like they can remember what they have lost, and that they can grieve without fearing further waves of arrest, kidnapping, or oppression.

IG: I absolutely agree. There is no other way. I don’t know how to explain this to the international community and international institutions: without justice, nothing can be done in a constructive way. This was the theme of my presentation during the Reconstruction conference, to which Philippe Sands, the other member on my panel, responded by saying “welcome to the adult world”—a very strict and unexpected message. We Ukrainians already had a kind of “vaccination” to this because when the war first started, in 2014, it was invisible. I remember the tragedy of the Malaysia Airlines Flight 17, which was shot down by Russian-controlled forces in Donetsk, and had a lot of Dutch citizens onboard who died. In Ukraine, we all thought that this would be followed by a mandatory punishment, a tribunal. There were a lot of discussions in the media and in personal conversations at the time about The Hague, anticipating that this would be the turning point leading to the end of the war. Indeed, such a court case did take place—six years later—during which a number of individuals involved at different levels in the crime were sentenced—all in absentia. However, Russia has still managed to evade accountability. The perpetration of this crime transcended individual actions; it was part of the Russian army’s invasion of Ukraine in 2014. I have no idea how to deal with this kind of collective disappointment, what to do with our faith in international justice, or international institutions and courts. I have no idea what to say to my daughter, or to my parents, to people who are still more naïve than I am. I don’t know whether to be sarcastic or to make jokes about this. I have no solutions.

AA: I like this analogy in your book when you invoke the film The Human Voice (2020), in which the protagonist is talking on the phone explaining what’s happened, what’s happening, how they’re struggling, and then you find out that there is nobody listening on the other end of the line. Sometimes that’s how it feels when you make your pain so visible. Even to take a photograph in Syria can carry a huge risk, even to your life. Everyone wanted to upload videos, to show to the world: look at how much we’re suffering. But then, we started to realize that sometimes, nobody’s listening.

IG: Personally, I have realized that it’s not enough for me to deconstruct or criticize. Maybe because of my architectural way of thinking, I need to construct something. It is common to criticize grand narratives; researchers tend to be focused on smaller, human scales. But I think I’m quite bold; I want to build grand narratives. This seems to now be my mission. I have the knowledge and can allow myself to build grand historical narratives about Ukrainian culture, and Ukrainian heritage in general. This will be my modest “contribution” to the defeat of Russia.

Rendell, Jane, “The Setting and the Social Condenser: Transitional Objects in Architecture and Psychoanalysis,” Adam Sharr (ed.), Architecture as Cultural Artefact (London: Routledge, 2012).

Tom Rollins, “Syria’s uprising came from its neglected suburbs, now Assad wants to rebuild them,” The National, June 19, 2018, ➝.

Reconstruction is a project by e-flux Architecture drawing from and elaborating on Ukrainian Hardcore: Learning from the Grassroots, the eighth annual Construction festival held in the Dnipro Center for Contemporary Culture on November 10–12, 2023 (2024), and “The Reconstruction of Ukraine: Ruination, Representation, Solidarity,” a symposium held on September 9–11, 2022 organized by Sofia Dyak, Marta Kuzma, and Michał Murawski, which brought together the Center for Urban History, Lviv; Center for Urban Studies, Kyiv; Kyiv National University of Construction and Architecture; Re-Start Ukraine; University College London; Urban Forms Center, Kharkiv; Yale University; and Visual Culture Research Center, Kyiv (2023).