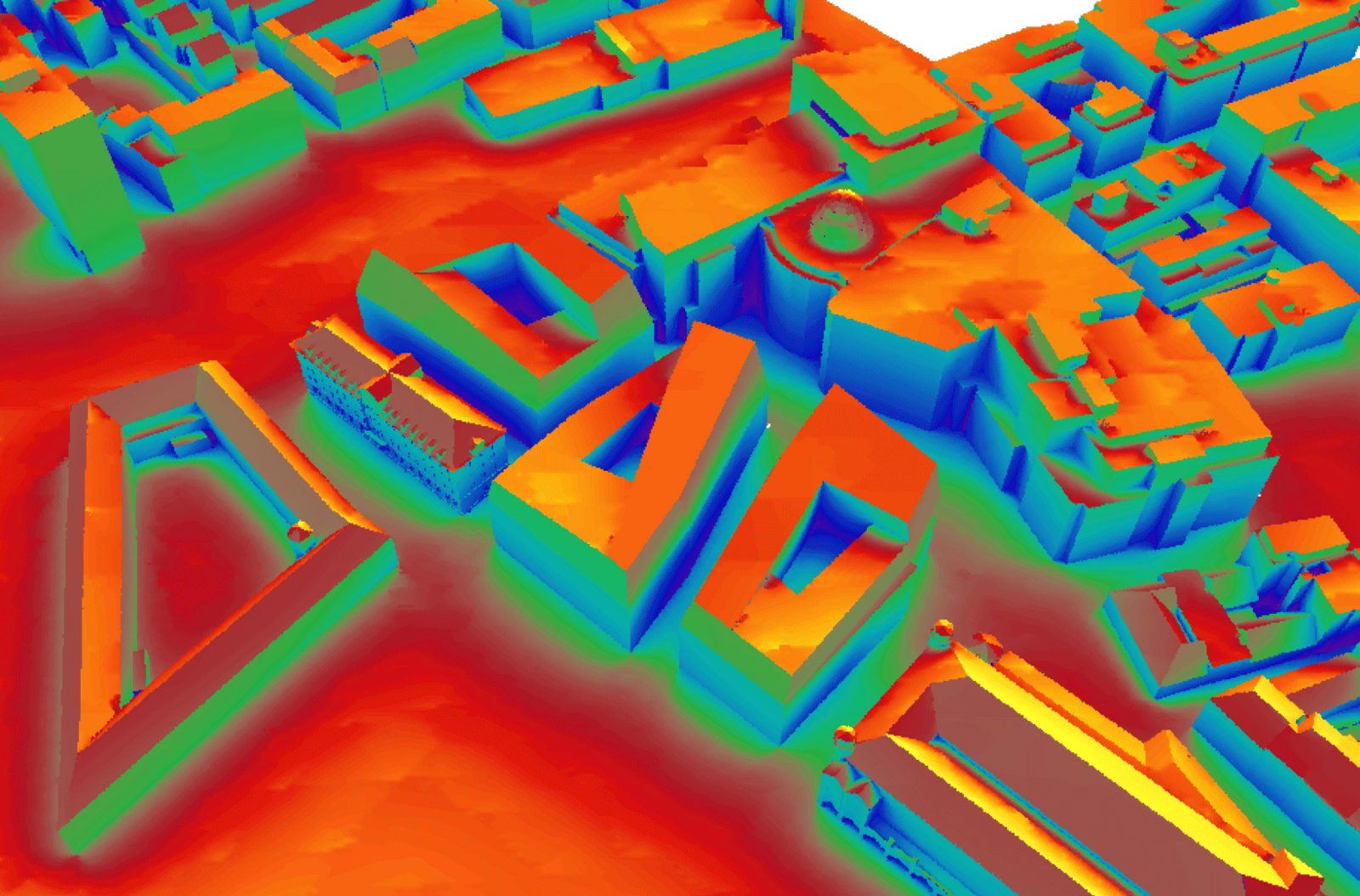

Architecture today is addicted to four basic products: steel, concrete, glass, and plastic. Each is a figure in the hyper-industrial world in which we live. We are living in the golden age of the Quadrivium Industrial Complex.

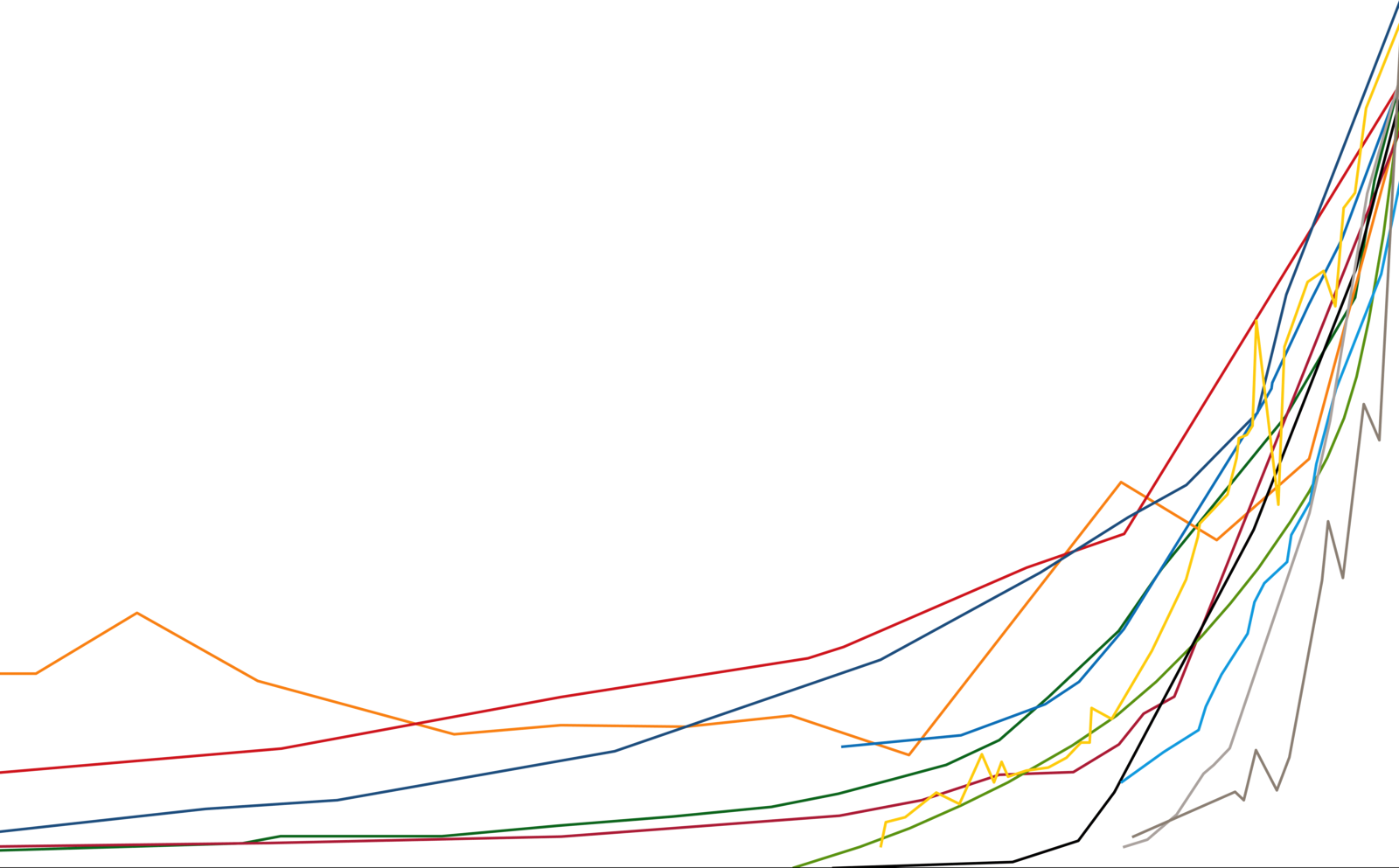

Though imagined by Modern architecture, it was only in the end of the twentieth century that the Quadrivium became unquestioned universals, made so by great global corporations in alliance with the rise of neoliberal globalization. Cheap steel was produced first in Korea then in China. Holcim came to dominate the global concrete market, selling concrete by the ton. The heavier the concrete the better—as far as profit is concerned. Steel became stronger, allowing less material, longer spans, and quicker construction time. Sheets of glass have become stronger and more resistant to e-radiation, and are now the cheapest way to cover a building’s surface. And rubber and other oil products including foams of various types hold the glass in place and keep the water out. Never in human history have so many different materials been mobilized so effortlessly.

Yet this golden age will not last forever. There is already concern that the world is running out of the right type of sand for concrete.1 And the shelf-life of rubber for caulking and window mullions is no more than thirty years, forcing buildings to be reglazed all over again. As one specialist wrote: “Modern glazing systems provide high performance and durability when they’re manufactured and installed correctly, and require very little maintenance in the first 10 to 20 years in service. Unfortunately, this is when the party often ends.”2

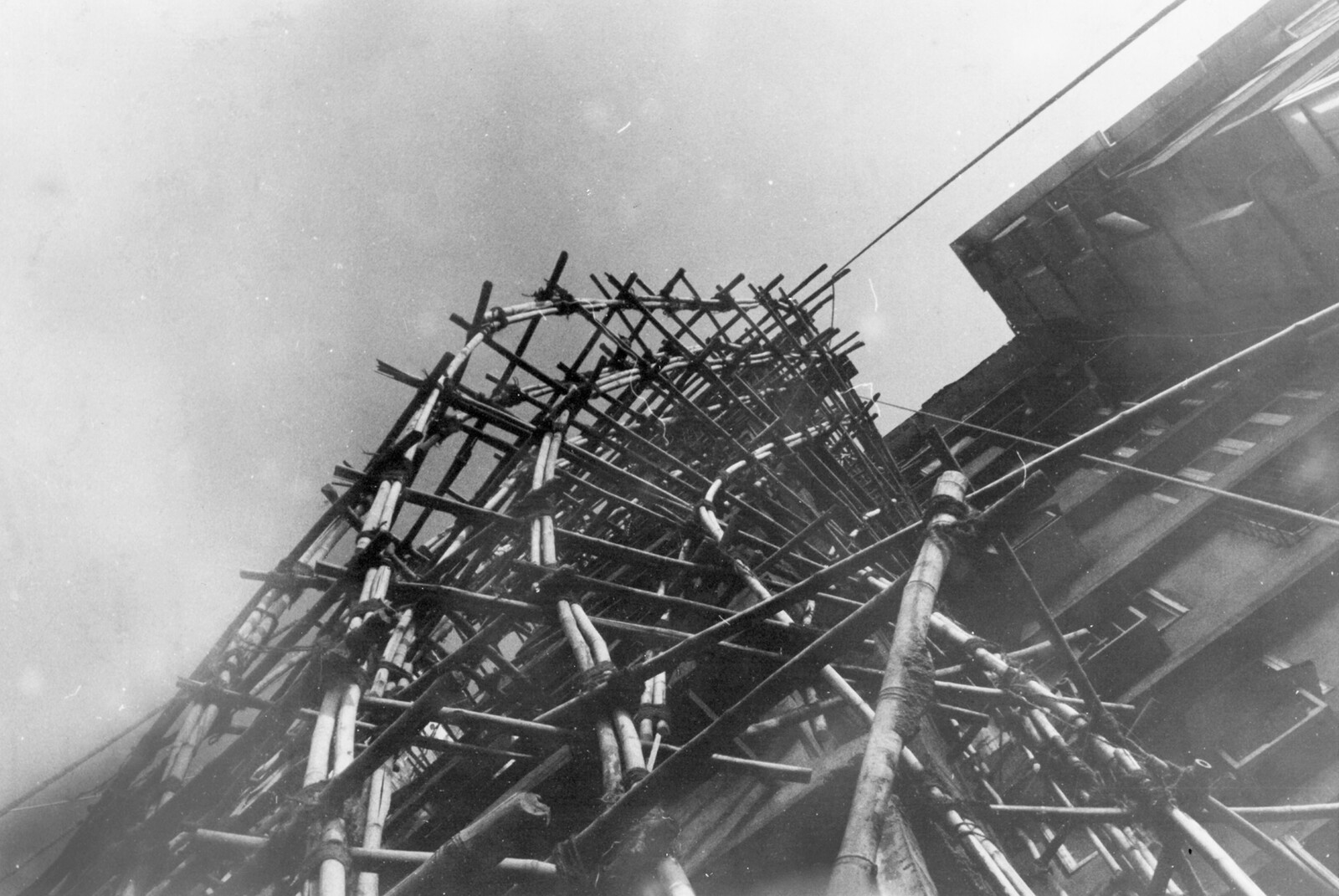

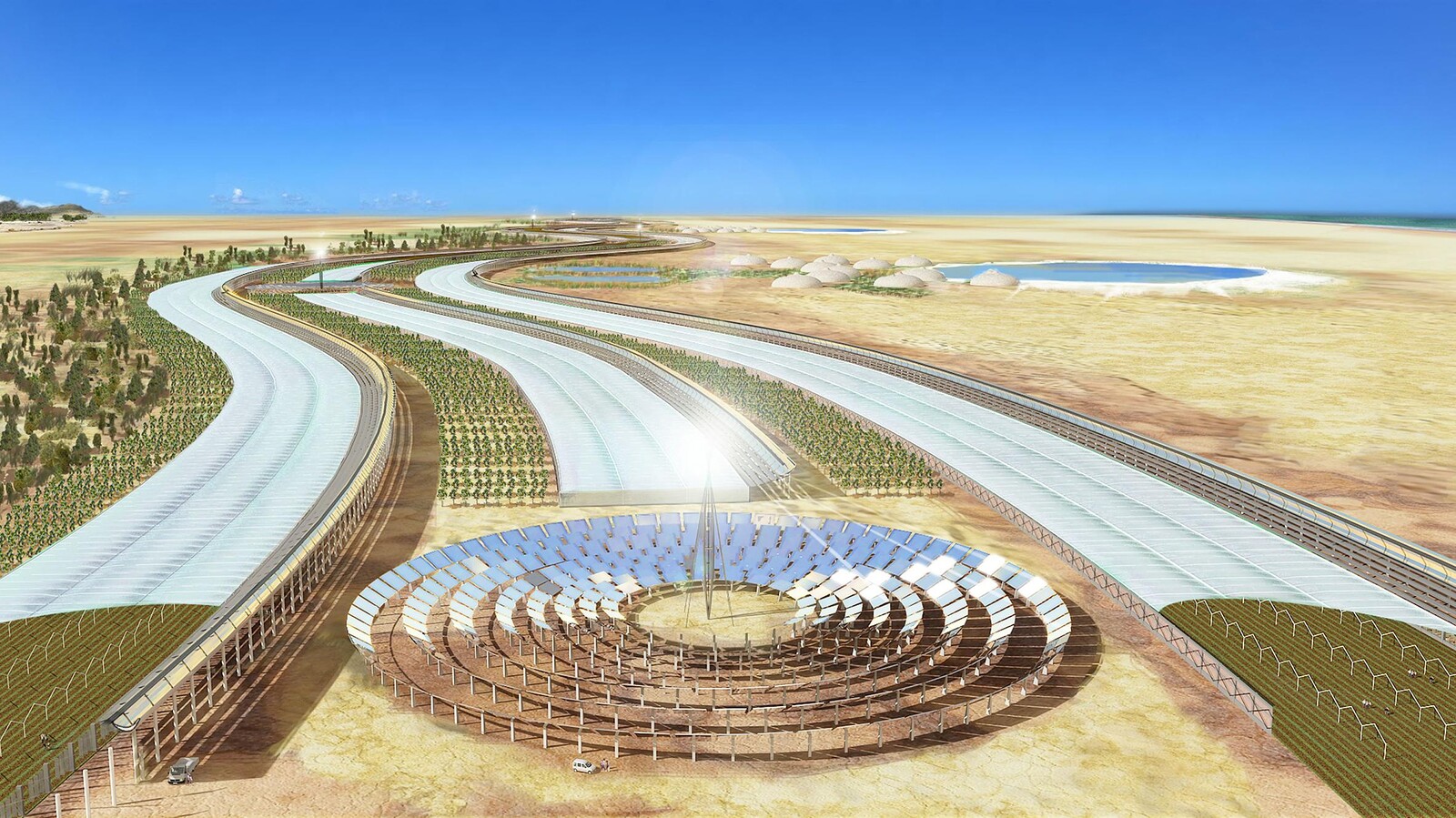

Imagine a world without the Quadrivium. Elites would still live in buildings of stone or brick—assuming those materials were relatively nearby—and there would perhaps be some iron ornamentation, but the rest would be living in structures made of sun-dried brick, wood scraps, earth, thatch, and bamboo. Forests would be decimated for beams or posts. Quarries would be abuzz with activity, and millions of people would be employed at river edges making bricks. Nation states as we know them would be different. Steel alone lies at the political foundation of Europe and the United States. Thank god for the great Quadrivium! Skyscrapers in the desert? No problem.

In the thirteenth century, huge portions of the globe consisted of oceans, savannahs, deserts, ice flows, and rainforests. These ecological zones were not mastered by so-called civilizations, but by the people European colonialists often called primitive and savage. These zones sat on extraordinary wealth. And as it turns out, they still do. Lumber from the forests, gold mines on sacred land, copper in the mountains, oil in the Arctic. Modernization will not end until the furthest reaches of the globe have been placed into the orbit of the Quadrivium. All humans today are complicit in this reshaping of the earth into its chemical constituencies.

Steel comes, of course, from ore and an array of toxic chemicals, extracted from mines in dozens of places around the globe. Concrete, glass, and rubber are no less complex in their constitution and fabrication, each compressing within its materiality a vast array of chemicals. Should we map even a single building backward, against the grain of its production—back to its molecular origins—we would find a dizzying global operation. Yet it all ends with heaps of stuff at the building site, waiting to be moved, lifted, and, assembled by impatient contractors.

The Quadrivium celebrates itself as a sign of mankind’s industriousness. It is set in motion by little more than a line stretching across a computer screen, activated by single tap on the “Send” button. A few electrical pulses and the supply chain responds with alacrity.

Designing even a large building today can almost be done in our sleep, so to speak. Most of it is automated through spreadsheets, CAD drawings, and computational algorithms.

Tons of the great Quadrivium wind up in landfills. Building material accounts for half of the solid waste generated every year worldwide, and the volume is expected to increase to 2.2 billion tons every year by 2025.3 More new buildings means more old buildings to throw away.

Let’s make a monument to our ingenuity; to the digital, chemical, corporate enslavement of the planet.

Let’s call it: Architecture! (A bizarre word in this context, since its ancient Greek meaning derived from the by-now obsolete trade known as carpentry.)

Architecture is zombified space, dressed up here and there in the shiny armor of “design excellence.”

Every inch of architecture is a stich of our guilt.

This guilt only becomes worse when we ask the wrong questions. Louis Kahn once famously wrote: “What does a brick want to be?” No question has even been more injurious to the field of architecture than this one. It assumes that the brick is mute and that the architect can divine its inner ambition. The question is spoken by a master addressing a slave. The brick, tricked into thinking it has an inner voice, now, in the silence of its response, welcomes its shaped, load-bearing servitude to the architectural mind.

The question should have been: “What does a brick have to say?”

Perhaps more relevant to today’s architecture: “What does a steel beam have to say?”

Would it tell us of the mines that sent contamination down into the streams below? Would it tell us of the lung cancer that the miners contracted breathing in cadmium fumes? Would it tell us of the corruption that was needed to quicken its unloading at the dock? Would it tell us of welders who sweated over their beads? Would it tell us the jokes of workers who sat on its beam a thousand feet in the air? Would it tell us the magic of the great chemical bonds that define its molecular existence? Would it tell us the governing logic of its alloy? Would it tell us of the great heat of the forges, or the cool spray of the presses? Would it tell us of its fear of water and fire?

Would it tell us of its hatred for glass? Would it tell us of its humiliation by the fire-retardant materials that cover its body supposedly for its own benefit? Would it tell us of its disgust for sheetrock? (Though sheetrock might have a very different perspective on the matter!) Would it tell us of its dreams about Eiffel, or its nightmares about being packed in aluminum cladding? Would it tell us of the arrogance of the architect or the builder who has never once run a finger along its smooth edges, who never once asks it what IT has to say, who never put an ear on its surface?

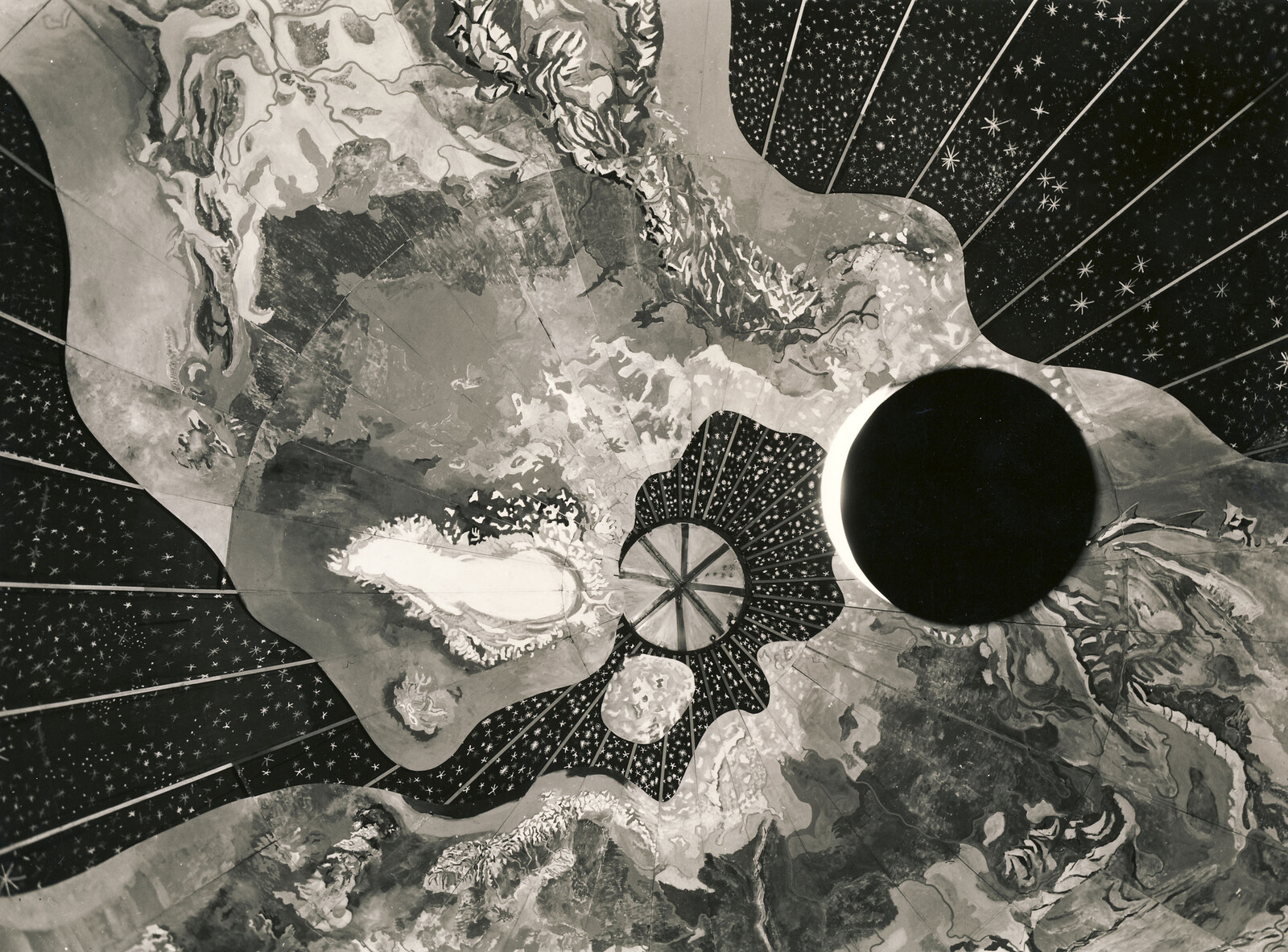

Would its iron tell us of the exploding super-nova some trillion light years away where it was first formed before tumbling through space for billions of years and violently colliding with our planet? Would glass speak of its ancestral rock that was formed three million years ago? Would it sing of its astonishing metamorphosis from non-transparent to transparent? Would concrete remind us that the ancient Inka world for stone was “flesh,” and that only recently we have come to see its constituent elements as dead minerals? Would oil speak of its hundred million-year-long warm, dark slumber, of its rude awakening, and of terrifying journeys through pipes, heating chambers, and extrusion machines? Would it lament the absence of a monument to its polymorphic capacity to hold the world together almost invisibly in the form of Epoxys, seals, foams, gaskets, and tubing? Would it tell us how underappreciated it is by the other members of the great Quadrivium? In an opera, oil would be the tragic figure. Maybe that is why it curses its colleagues with a thirty-year limit.

The Quadrivium Industrial Complex denies the speech-carrying capacity of materials that it produces. It embodies a paternalist modernity that houses the world in architectures of silence. Even sustainability is often little more than a perpetuation of Quadrivium’s teleological assumptions, filling in the blanks toward a world under its complete domination.

How to communicate differently with the materials that we create and harness? How to extricate ourselves, as designers, from the by-now-naturalized linkages between rationality, modernity, and coloniality? How to dismantle the historically-conditioned, scientifically-grounded, unresponsive, corporatized core of the Quadrivium, all in anticipation of its demise and collapse?

Greg Brown, “A global sand shortage could cause damaging effects to our rapidly urbanizing world,” Business Insider, January 16, 2019.

Brian Hubbs, “The Inevitable Issue Most High-rise Owners Face,” RDH Building Science Inc, March 10, 2014, ➝.

Adam Redling, “Construction debris volume to surge in coming years,” Recycling Today, March 5, 2018, ➝.

Overgrowth is a collaboration between e-flux Architecture and the Oslo Architecture Triennale within the context of its 2019 edition, and is supported by the Nordic Culture Fond and the Nordic Culture Point.

.jpg,1600)

.jpg,1600)