Nikolaus Hirsch The notion of time seems to be very essential to Rotor’s practice. Your work on material cyles provides a different understanding of what architecture is, or building in a broader sense. Your practice is not just about the tip of the iceberg of buildings that we can describe as architecture, but potentially tackling the whole of the built environment. How would you define your practice, the role you play within the field of architecture, and within the built environment at large?

Tristan Boniver Up until two years ago, I would have told our story one way, but I don’t tell that story any longer. The story until then was that materiality, or the built environment, has an entropic life cycle: things get used, maybe reused, and then turn into rubble. We used to position ourselves as a retardant, slowing down this process. But a lot of our projects have less to do with matter itself, and more on practical questions. Reusing architectural elements is a practice that is as long as the history of mankind. At one point, midcentury, this practice started to disappear. Industrial progress, capitalism, evolving demographics, and culture led to a different paradigm of practice. We’ve never seen our approach as one of invention. Our practice is more today about rediscovering existing practices. We see ourselves trying to connect the past to potential futures.

Nick Axel What are some of the challenges that you face in trying to reintroduce this longer historical continuum into the amnesia at the present?

TB You would think that the challenge is to convince people, but it’s not. Ideas about sustainability, reuse, and so on are pretty well established. No one’s against doing it. The obstacles are in the administrative procedures. Those have a lot of inertia.

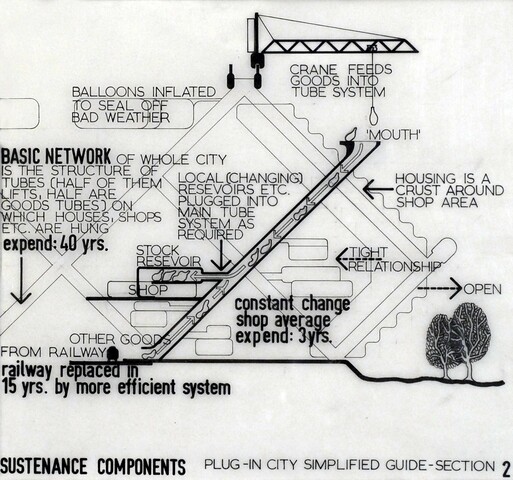

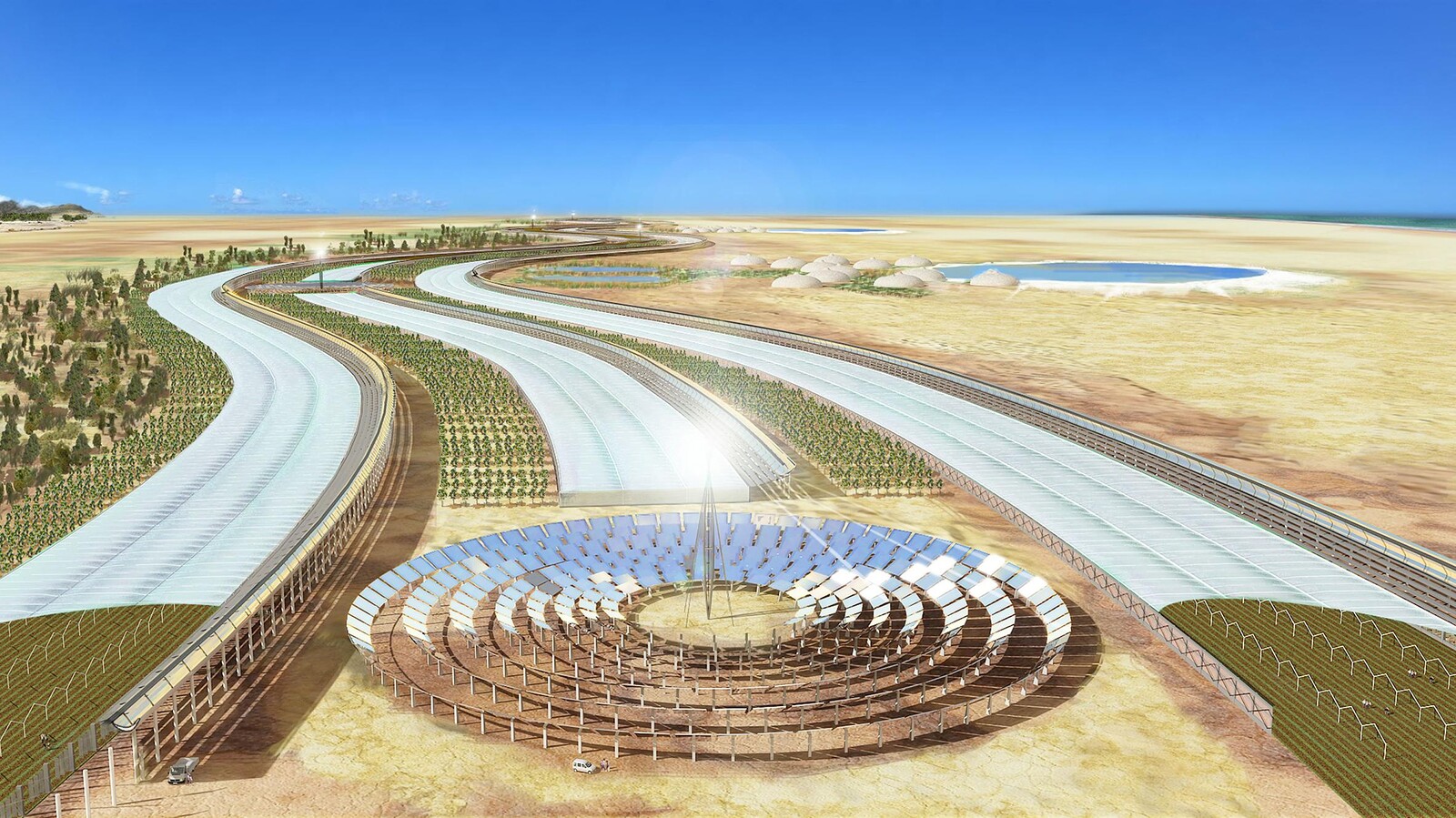

Archigram, Plug-In City, Sustenance Components, Simplified Guide Section 2, 1964.

NH Codes and regulations?

TB This is a cold, boring, unaesthetic, and unspectacular area of inquiry and practice. It doesn’t give much in terms of visible or tangible results. Did you know that it used to be illegal to use salvaged materials in public projects and competitions in Belgium? We had to work with a lawyer for two years to make it not forbidden to use reused materials and components in building projects.

NH These types of things are hardly visible, but they are the foundations of what is possible in terms of architecture.

TB Law is a kind of restriction, one that has slowly enclosed and protected a set of conditions from previous realities. But regulation isn’t organic. Lobbies push agendas into law.

NA So regulation isn’t just pragmatic.

TB It’s not universal. A lot of codes and laws need to be questioned. But, as you pointed out Nikolaus, it is a reality that many practitioners rely on. There is understandable resistance from people who have the burden of change, but they make it impossible to renew architectural practice for the twenty-first century.

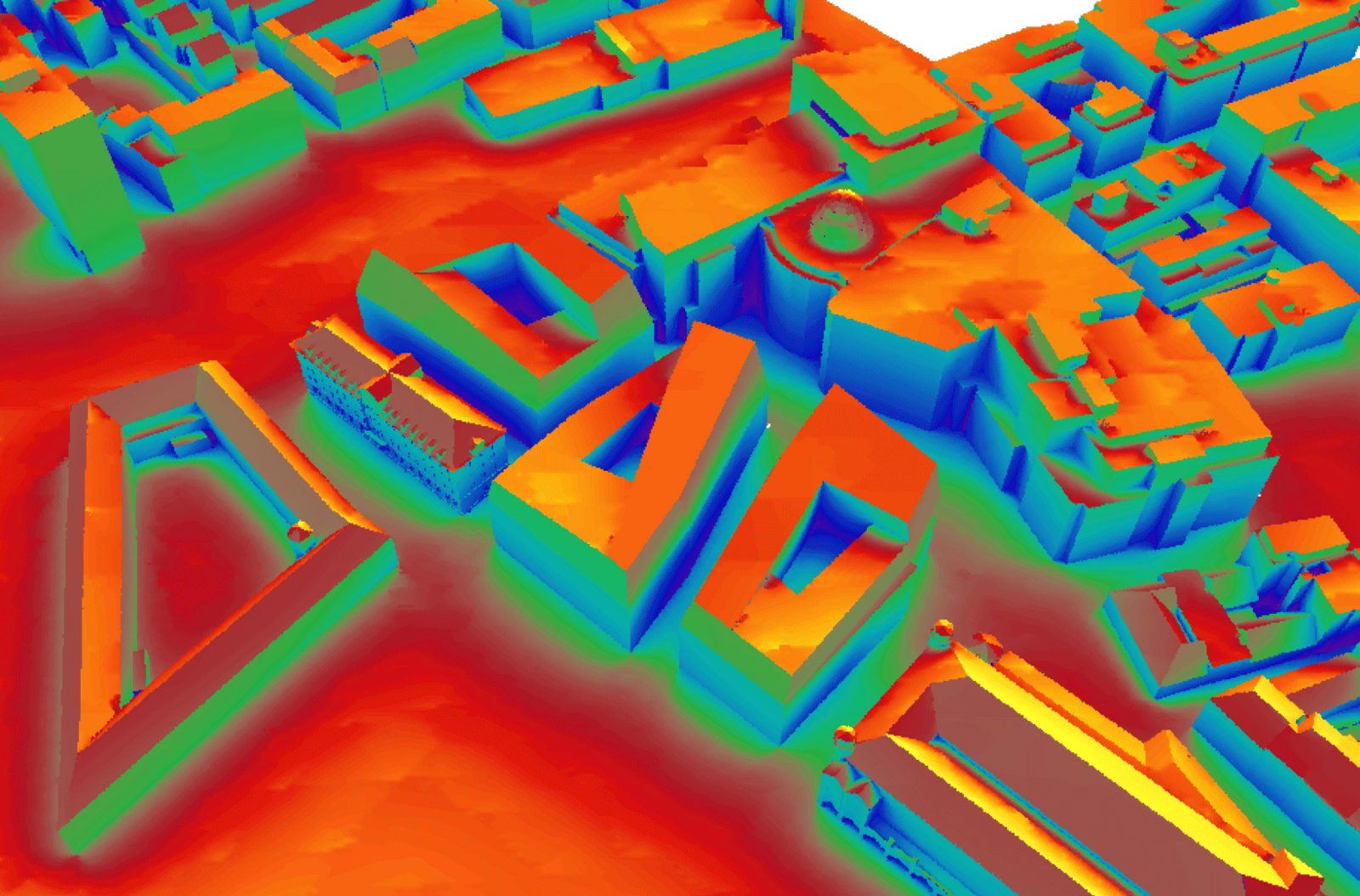

RotorDB, Advertising for Elements. Source: RotorDB.

NA That needs to be an incredibly sensitive practice. History is written by the winners. If laws were to change to allow materials to be recycled and components recirculated, we would also want those regulations to have the same inertia, if not even more durability than the laws which now prevent that from happening. But you’ve practiced this, and been successful in numerous ways. What has it been like to work on the level of designing governance?

TB One example of this type of our work is Plateforme Réemploi, a project we did for Brussels-Capital Region that we did with the Belgian Construction Federation and Atelier 4/5 (a Brussels-based architecture agency) in 2017. It was produced within a governmental framework that funded the creation of a policy document to expand the legal possibilities of reusing building elements. This is actually what opened us on to develop our historical perspective. We worked with a lawyer for a month, who helped us create a sixty-page document that plugs into the existing legal framework and allows practices and public entity to use reused materials. The results were very, very boring. In the end what we were left with as a project was a stack of bureaucratic forms. This is immensely important work that we are deeply committed to, but we also do other types of projects, ones that allow us to design, to breathe.

NA How would you describe the composition of Rotor?

TB Rotor is like a two-headed hydra. One part of the office is a more typical studio, with projects that come from our interests, the market, and commissions. Here we do research, make exhibitions, and build architecture. Then we have another part, which was originally a spinoff of the first, but is now a relatively independent commercial entity that is plugged into a different level of architectural practice. We actively dismantle buildings before they are destroyed and warehouse the parts we can extract. We have 3,000 square meters of a logistics warehouse with clerks, forklifts, a showroom, and an online store. The trick is to be there before it’s too late in the process of demolishing buildings. One part of this team actually takes buildings apart, on site, and brings it to inventory. The other is out there building relationships and trust within the real estate sector.

NA How they relate to each other in practice?

TB They’re two distinct companies: Rotor and Rotor Deconstruction. This means so that if Rotor takes on a commission and wants to use some elements that are in Rotor Deconstruction’s inventory, Rotor is just like any other client. We don’t sell to ourselves at a financial gain. That’d be illegal, of course. We purchase everything at full price. We play the game. We want to demonstrate that it is financially viable.

Rotor, Plateforme Réemploi, 2017. Source: Rotor.

NA You can find stores that sell salvaged architectural elements from historical buildings, like Victorian friezes or art deco handrails or whatever, in almost every city. What’s the difference between these places and what you do? And how do you balance supply and demand? Or do you find some elements sitting in stock. These antique stores tend to get quite dusty!

TB To be honest, it’s more a problem of demand than supply. Office space in Brussels tends to have a turnover of two years. The amount of material that is usually thrown away with every change of occupancy is immense. But we don’t take everything. You have to know where the crème de la crème is. We’re very selective. With an inventory practice, optimization is crucial. You don’t want to bring in three palettes of material that you won’t be able to sell. Our approach is not the sentimental or contemplative one we had ten years ago, that we exhibited in Venice, where we fell in love with element and hoped that others would too. People did, but it wasn’t enough as an architectural practice. We turned the elements into artworks, non-functional design objects. In order to run an architectural practice out of this, we realized that we have to look at thing that we think are fantastic but let them go. Maybe it’s too heavy, or on the seventh floor and too difficult to get down. We’ve worked to create a market, and it’s demanded that we develop much more pragmatic senses.

NA There was a certain point when, as you said, something happened; that this idea of reusing materials disappeared. In this regard, one of the most iconic canonical images is, for me, the cross-section of Archigram’s Plug-In City, the one that labels the lifespan of each element-five years, two years, three months, etc. With this practice of critical judgment you’re now undertaking-deciding what is worth taking and what is not-do you think architecture could ever become 100% recyclable? Is the complete, autonomous circulation of architectural elements possible, or is there some necessary waste?

TB There are two practical approaches to this question. One is to make architecture as reusable as possible. The other works with what’s already there, making tangible what we don’t see. While the first approach, of making buildings reusable is perhaps much more forward thinking, it has an unsuccessful history. It is also especially fragile in our current economic conditions, where aesthetics change rapidly and norms evolve. Even in the perfectly dismountable building, you can’t know if its elements will be reused in thirty years. And if they are, it won’t be because it’s modular. It might be because of the floor height, the HVAC or electrical system used.

NA But there is certainly need to inject new components into architecture’s material economy.

TB Absolutely. Maybe not in the conventional sense, but we do that too. We were working on the interior design of an office last year where our components, and in particular wall partitions, didn’t quite fit. The commission dictated the size of the spaces, so we knew the run of walls we needed to make. We worked from our inventory, but each of the elements have strict dimensions. Fitting pre-existing elements into an existing space is rarely straightforward. We had to develop a ways to use the components, which in this case buffering a gap of space that existed between the wall partitions and the columns. For a while, around the turn of the century, glue was the answer. But architecturally, this act of filling in a gap needs to be custom designed. We developed a technique of overlapping the partitions with cork. This allows them to be very adaptive, while at the same time giving it a simple aesthetic.

NA Is the in-between a new kind of component to design? It doesn’t sound like there can be any universal solution.

TB It’s more about inventing a new paradigm of intervention rather than thinking of something that can be designed and scaled up. In the office project I mentioned, we shifted budget away from rebuilding, from buying elements, and towards collaborating with craftsmen. For the same budget we did it differently.

NH You seem to always be measuring things. How important is economy in your work?

TB It’s permanently on our minds.

Overgrowth is a collaboration between e-flux Architecture and the Oslo Architecture Triennale within the context of its 2019 edition, and is supported by the Nordic Culture Fond and the Nordic Culture Point.

Category

Subject

This interview took place during the e-flux conversation series Practice at Milano Arch Week 2018.

Overgrowth is a collaboration between e-flux Architecture and the Oslo Architecture Triennale within the context of its 2019 edition.

.jpg,1600)

.jpg,1600)