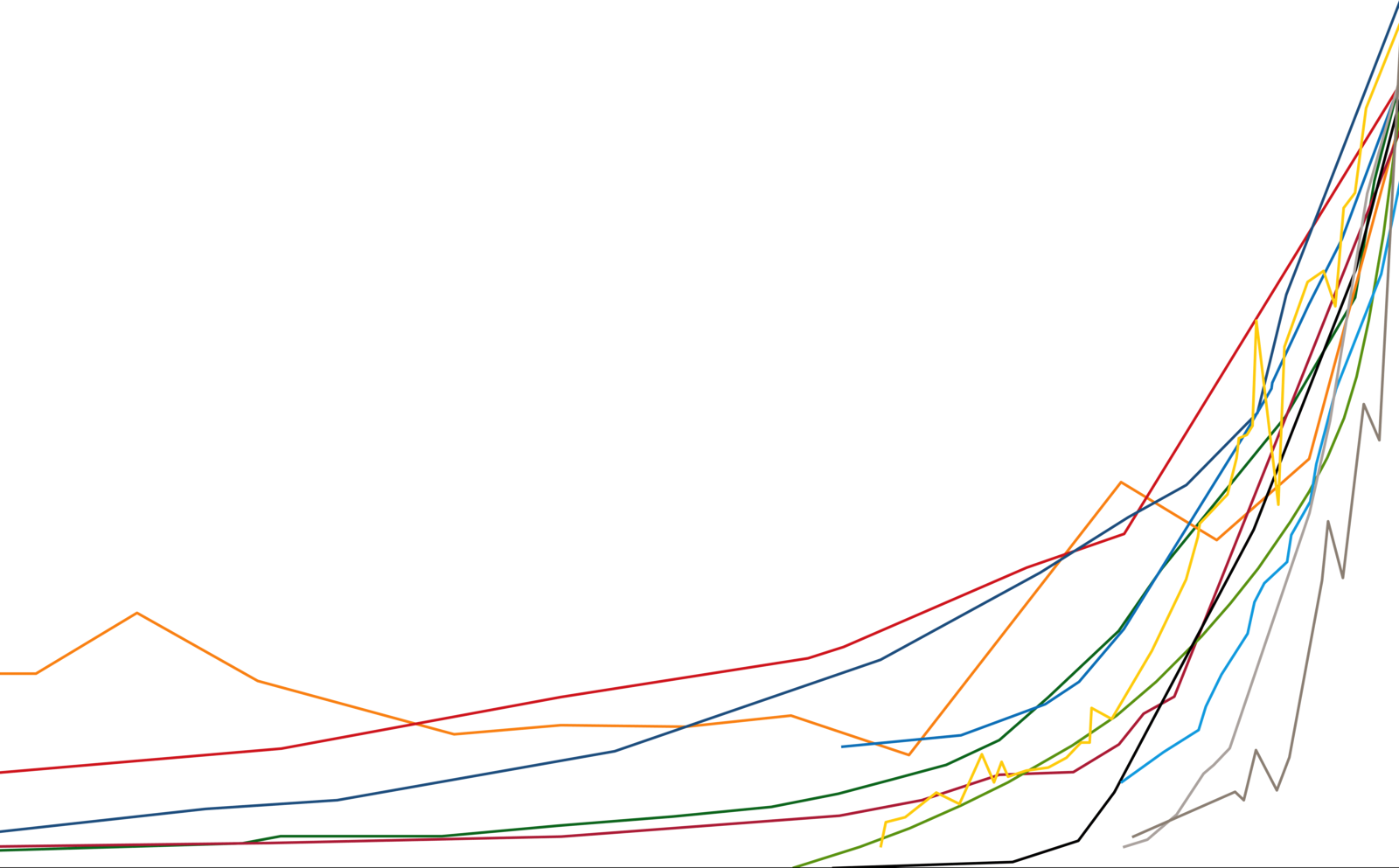

We will look back at these times from the future with total bafflement. There is abundant and ever-mounting evidence of the devastation our way of life will bring to both us and the planet—all far too familiar in their many interlinked dimensions to require rehearsing yet again. Yet we are still doing far too little to avoid what is forecast as certain disaster. Instead we are like rabbits paralyzed in the headlights of an oncoming car awaiting the demise of all we profess to hold dear with resigned fatalism. The reasons for inaction are various. They include the blocking actions of vested interests—rich corporations and the wealthy elite—that benefit lavishly from the present situation. In this they are aided by supine politicians and neoliberal dogma—how were we ever gullible enough to believe in and accept the latter, even in these confused times?

More pertinent are other factors. The multiplicity of solutions offered is hopeful and enticing, yet also confusing and disempowering. Which of all these will be effective? And aren’t they too partial, piecemeal and disconnected? Such reservations are valid and apply to ideas surrounding degrowth and so many other eagerly proposed contributions to meeting the challenges of our times. But the real problem is that they are not part of a larger framework or strategy for effective action, in particular one informed by an inspiring and integrative vision of what might supersede the status quo. Equally disempowering is recognizing just how great are the challenges we face. Daunting too, is to acknowledge the profound changes required if we are to approach anything resembling the many dimensions of true sustainability and bring about the transformed mind sets and ways of engaging each other and the earth that will deliver it.

What we recognize, or perhaps mostly intuit subconsciously, is that we must navigate what will prove to be probably the greatest of pivotal shifts in human history. This will involve changes in the way we live and, perhaps more to the point, who we think we are—our very identity and sense of belonging. These shifts must be at least as great as those accompanying the move from the nomadic tribes in which we lived for most of human history to the agrarian settlements we pioneered only 10,000 years or so ago. Also entailed will be modifying, and even inverting, many of the ways of thinking and being that have defined us to date as humankind. But if we ponder all this, it should be as exciting as it is scary to enter a new phase in the human evolutionary adventure. Yet the enormity of what could be promised and its enticing possibilities provokes resistance to participating in this adventure, particularly amongst those let down by the non-delivery of previous promises.

To understand where we are historically and how we got here, and to guide what we do now, we must adopt a Big Picture perspective, a much larger spatial and temporal frame of reference than usual—in short, an evolutionary and ecological view, so seeing things as unfolding over time and within multiple webs of interconnections. That we now deny our many interdependencies with the world around, including nature that evolved us, is a consequence of our earliest days as a species characterized by an extreme vulnerability, particularly that of our defenseless and long-dependent infants. But we are also blessed with curiosity, creative intelligence and the capacities for learning and communication which we used to defend and distance ourselves from the dangers of the world around.

We imagine early tribal people lived in harmony with surrounding nature—and they did so in considerable degree. But even then, language alone would have started our long and progressive separation from nature and the world around. An animal is enveloped in an omnipresent world; but, thanks to language, we live in the world, the addition of the definite article pushing the world away and separating us from it. This separation was enormously compounded by our various forms of construction for defense and shelter as well as by our various technologies, such as our early mastery of fire to banish cold and darkness and keep wild animals away.

Yet the whole world around was still our home to be treated with respectful and reverential gratitude, and propitiated with rites that recognized and took responsibility for our interdependencies with nature. But the establishment of agriculture and settlement started a progressively greater separation from the nature that we tried to conquer and control as we wrested a home for ourselves from what came to be seen as “other” and even hostile. This separation intensified with the foundation of cities, most obviously those behind defensive walls, where separation also manifested in the stratification of, and internal divisions within, society. Modernity took all this to another extreme.

If modernity were distilled to a single core concept it would be that there is an objective reality independent of us—the same assumption underlying classic, reductionist, mechanistic science, what some now call scientism. Prior to the rise of science this exclusionary view of reality would have been incomprehensibly weird, as it is again today to any who have really grasped the implications of leading edge contemporary science, such as quantum entanglement. The extreme dualism of an assumed objective reality alienates and excludes us from the world around, inhibiting our sensual and empathic engagement with it and so sense of responsibility for it. Of course, this objectivism also provoked a counter-reaction in an exploration of the subjective in the modern novel, psychoanalysis and so on. But although such subjectivism characterizes much of modern artistic culture, it has remained subordinate to the dominant narrative of an objective reality and the elevation of rational consciousness—still the mind-set of economics, medicine and much else.

Elevating the objective as true reality, so suppressing the subjective realm of empathic and other experiential connections, led inevitably to the fragmentation of the world into isolated objects, thought to be fully understandable by analysis and dissection when abstracted from context. The consequences are starkly represented by modern architecture and urbanism, fragmented into isolated freestanding buildings whose abstract forms relate to neither our human bodies nor their context of neighboring buildings. In such architecture, dwelling and all its rich psychological resonances is reduced to mechanistic function—detachedly observed activity. This is accommodated in “efficient” plans minimizing circulation, cores and wall thicknesses, and ignore other efficiencies such as energy consumption and all those others revealed by total life costing. And its enveloping thin glass skin plays no symbolic or other communicative function of a proper façade whose composition addresses and holds space before it, nor performs its place-making role by connecting and creating a sense of place inside and out.

All these dehumanizing tendencies are consistent with a world view that also fragments us (mind from body and so on) and excludes much of who we are, so we don’t sense we belong to a world that is not shaped to be lovingly embraced and cared for. Seeking solutions to the challenge of sustainability in such exclusively objective dimensions as technology and ecology, while neglecting these crucial psycho-cultural dimensions, explains why we have made so little real progress. To our concerns for nature and the planet, and how these can regenerate and flourish, we need to add concerns with our own flourishing, psychologically and spiritually as well as physically. We need to redefine what it is to be fully human, and what sort of culture and built environment will promote that by drawing on our latest understandings from multiple fields.

Many will balk at this emphasis on the human because prioritizing people at the expense of nature has led to our current precarious position—as movements like deep ecology correctly assert. But this human would not be that of modernity, desensitized by Enlightenment rationalism to see nature as mere resource for human exploitation. Instead it would be a redefined and re-sensitized human who becomes fully alive in the open-hearted embrace of nature that evolved us and of which we are intrinsic—as well as by living in a re-humanized architecture. Such a human finds deep meanings, purpose and fulfilment not in the exploitation of nature but in treating it as a co-creative partner in a dialogue that seeks the flourishing fulfilment of both planet and people. Hence the sustainable architecture of the future will not be sought in hovering buildings with minimal, gentle impacts on soil and setting, or Hobbit-like habitats that disappear into nature, two trends that today many mistakenly assume are epitomes of green design. Instead, confident that we evolved as belonging to and intrinsic to the earth so as to contribute to its continuing evolution, our buildings will be benign presences in dialogue with their setting to add new dimensions to nature and us as flourishing together in symbiosis.

The now waning modern era brought huge benefits—too many and too obvious to require elaboration. Amongst these gifts are the vast amount and various forms of knowledge it generated, but also compromised in its usefulness by quarantining it into specialist silos. Yet behind these many benefits are downsides that have not only become increasingly obvious but now threaten all that we treasure. Looked at from a Big Picture perspective of where we have come from, and the continuities and changes suggested by the knowledge explosion that is one of modernity’s greatest gifts, it becomes clear that modernity is not the beginning of something new but the end of something old. It is the terminal climax of the progressive distancing of us from the world and hubristic denial of our multiple interdependencies with it. The problems we face, such as the challenges of progressing to sustainability and dealing with other interlinked forms of systemic meltdown, are not accidental by-products of modernity. They are utterly intrinsic to it, along with the unavoidably inevitable consequences we now face.

Separation from the physical has now reached a pathological extreme with such developments as virtual reality and smart phones. The latter, of course, bring huge advances in social connectivity and access to information, but also, in their manufacture and disposal, enormous ecological damage and the erosion of face-to-face communication, along with the pathologies that attend that disconnect. Moreover, these devices have caused many to withdraw further from the world and their bodies, retreating into their heads and following only news feeds that flatter and reinforce their prejudices, so betraying the promise of being better connected and informed.

Another manifestation of separation is social stratification in status and income, and the extreme inequalities in wealth and opportunity that are another betrayal of modernity’s assumed promises of egalitarianism and emancipation. This fuels the rampant rage, arising from a sense of exclusion blamed on immigration and so on that has brought about Brexit, Trump, and the rise of right wing populist political parties. People recognize that this could be a time of opportunity for all—the wealth, knowledge and technology exists, if only access extended beyond elites. People are widely, if dimly, aware that theirs is a half-lived life, much less than what our professed ideals promise everybody, and not in line with contemporary expectations of the flowering of each individual’s talents. Such dissatisfactions drive a desperate consumerism and other forms of addiction, as well as a disregard for larger social and ecological consequences, that must be dealt with before anything approaching sustainability becomes viable.

All these and other problems with modernity, such as dismissing negative impacts like pollution as externalities for others (taxpayers) to clean up in the future, explain how a once vulnerable creature that had to distance and defend itself against a threatening world has become the major threat the rest of creation now needs to be defended from. So what do we do now? Firstly, recognize the deep truth of what Einstein said: a problem cannot be solved by the same level of thinking as caused it. Our problems are the direct consequence of modernity. As such they cannot be solved by modernist thinking, by objective and technical means alone. The modern world and its systems at one level seem stable and secure, but are in fact very precarious—as would be quickly revealed by the tiniest glitch in a supply chain, for instance. And the systemic meltdown that is widely anticipated, and arguably is already underway, going far beyond devastating environmental problems, can be optimistically seen as marking the terminal phases of the modern era. As such it is also a blatant invitation to all responsible and creative people to participate in shaping a new era.

Besides the understanding a Big Picture perspective brings, we need an inspiring and integrative vision of what is now possible, drawing on all the insights and techniques brought by modernity to devise ways to help us and the world flourish. If this vision is not truly inspiring it will not spark the impetus and persistence necessary to being realized; and if not integrative it will not add up to anything beyond a carnival of disconnected efforts. It is not, as some assume, that major investments are necessary to bring real change. These could no doubt help, but large and disruptive interventions are just as likely to provoke backlash and stabilize the status quo. By contrast, shrewd, small scale interventions may escape any such form of backlash to instead gather snowballing momentum and become unstoppable. Environmental campaigners too often overlook this. They focus on and are consumed by the problems that hover like a disempowering dark cloud draining our reformist zeal. But in the face of an optimistically sunny vision of inspiring possibility these clouds abate somewhat. The question then is what small step will initiate a snowballing momentum towards realizing the inspiring vision.

What would be this inspiring and integrative vision? An obvious place to start formulating it would be by inverting millennia of progressive separation, with its debilitating and alienating consequences, to reweave a rich web of relationships of all sorts to create an all embracing, dynamically evolving whole—that includes the broadly cultural and the more narrowly environmental—in which everything has a place and plays an essential part. Such an enlivening and ennobling vision is commensurate with the emerging view of a living universe, the antithesis of Newton’s mechanical universe that underpinned modernity. Newton is essentially dead and meaningless, the product of blind forces and random mutations, and is very different to a dynamically evolving, ever-creative living universe, such as the leading edge of evolutionary biology now subscribes to. The inevitable response to the meaninglessness of the former is to wall oneself off with consumerist goodies and distract oneself with entertainment and other addictions. But understanding the universe as creatively evolving and alive is encouraging to disencumber, engage with, and participate in these processes with minimal distancing and deadening defenses.

Moving on from modernity will mean rethinking the essential nature and purposes of much of our way of life. Thus design would be seen as not just about problem solving and serving function, as in modernism, or the lubrication of consumption it has degenerated into today, but rather as humankind’s way of participating in evolution. It is about divining the multitude of unfolding processes in the world around and helping these come to the most beneficial fruition as our view of creativity moves from ego-based self-expression to selfless participation in ecological and evolutionary processes. From such a perspective, it is clear how narrow and incomplete modern architecture is, reflecting modernity’s shriveled view of reality.

As is often said: whoever discovered water, it wasn’t a fish. Something similar pertains to architecture. Our relationship with it is so pervasive and intimate that even architects don’t grasp its deep originating purposes. As much as language, architecture played a key role in the creation of human culture, and so of us as complex, acculturated beings. It elaborated a complex world of diverse and intensified experiences and meaning for us to explore, internalize, and so expand who we can be. Now it is who we have become, as shaped by modernity’s mechanistic and impoverished world view, that causes the crises of our time. So it is time to rethink who we must become to heal the planet and ourselves, and how architecture and the city can help achieve this. This will entail transcending the modern notion of architecture as mere functional devices to once again be understood as cultural artefacts mediating our relationships with the larger world. Concomitant with this we must rediscover the vital and life-enhancing role of culture in giving meaning to our lives and reconnecting us across time and space, back to our origins, and even out to the unfolding cosmos. The revaluing and regeneration of culture, which was eroded and rejected by mechanistic science, is amongst the most important collective and collaborative challenges of the near future. Without this we will not achieve sustainability or become responsibly engaged citizens of our urban habitat or the earth.

Before modernity we lived in what could be referred to as the City of Being and Belonging, which amongst other things was also the crucible of culture, creativity, and consciousness. This is the compact, traditional city whose buildings line, define, and animate the public realm of streets, squares, and green spaces that are shaped in response to who we are so we feel that we belong and are at home. These elements of the public realm together form a coherent gestalt that is not mere residual space but is articulated to constitute the multiple stages of the theater of daily life. Within the contiguous fabric of spaces and framing buildings of such a city, we were the same persons wherever we were, known in all our aspects by all those around—an essential condition for acquiring self-knowledge and maturity. Most importantly, such cities served all of who we then were as humans, their experiential and symbolic richness nurturing the subjective self.

The traditional City of Being started to fragment with the impact of polluting and noisy industry, and as mechanical public transport allowed the better off to move to the suburbs. This and the impact of modern planning—initially a set of defensive measures to protect against insalubrious industry and over-crowded housing conditions—led to the dispersal and loosening of the tight contiguities of the traditional city. This has resulted in the fragmented modern City of Doing—and of Dispersal, Disconnect, and Denial. In this City, free-standing buildings are distributed in a conceptual void in which you play out different roles in different parts of the city: parent at home, employee at the office, and passive consumer in many other parts. The emphasis on distributed specific functions (Doing) results in a machine for avoiding the chance encounters, complexities, and contradictions that lead to self-knowledge and psychological maturation. It also disrupts the continuities of the ever-present, ever-experiencing self that is the subject of the City of Being.

To move beyond modernity, we need to recover the sense of community and belonging of the City of Being. Yet that such cities now seem so reassuringly right for humans is partly because they were shaped in eras of relative stability and not subject to destabilizing change. That change must be sweeping and urgent to belatedly deal with what confronts us suggests we need to retain some of the dynamism of the City of Doing while avoiding its downsides. This answer will be the City of Becoming, informed by an emerging and expanded sense of what it is to be fully human. This City will offer multiple ways to explore its richly diverse fabric and facilities and so discover ever more potentials in ourselves. The architecture of the City of Becoming will further expand and elaborate this role as it weaves a web of relationships in a way that encourages one to be aware and engaged, stretching you to all one could become. Instead of modernity’s isolated objects in a conceptual void, un-treasured and tarted up with smears of landscaping, the result would be a richly woven tapestry of relationships.

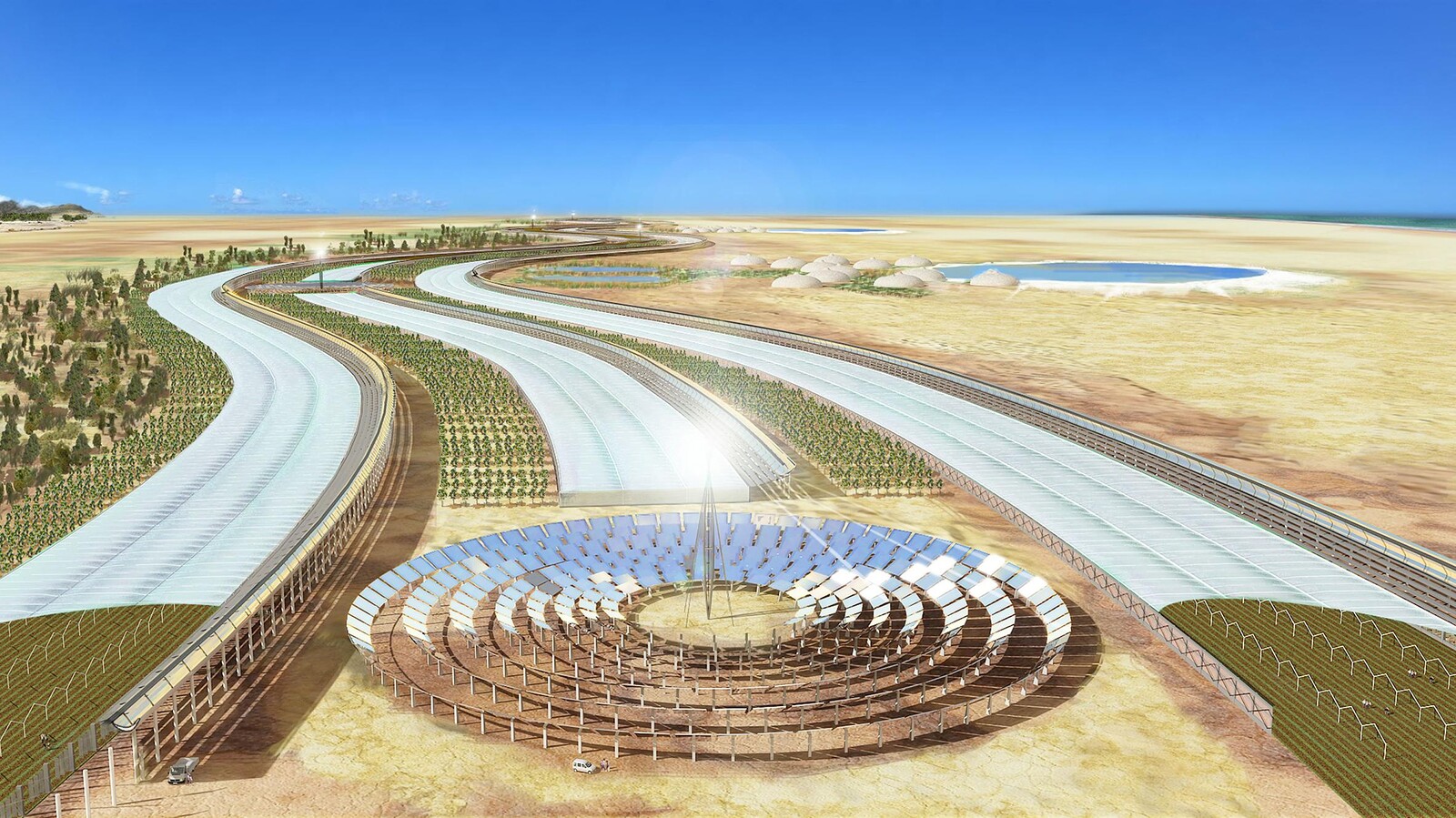

So what is to be rewoven? Pretty much everything, or at least as much as possible, both in the physical realm and within the psyche. Architecture, urbanism and landscape would regain the intimate interrelationships they enjoyed prior to modernity, but now informed by concerns such as sustainability and wellbeing. Architecture will not only once again frame and animate the public realm, but also harvest ambient energies such as sun and wind, retain and recycle rainwater, use plants for shading and air purification, and so on. Urban design will also temper climate as well as create a rich framework of different places, experiences, and meanings to be explored and enjoyed while expanding one’s self through our relationships to place and history. The city will also weave patterns of use and circulation to provide ample opportunities for social encounters and community formation while catering to the needs of people at all ages and stages of life. Landscape will contribute to climatic comfort and healthy hydrology too, but also enhance biodiversity and even contribute to food production, if only by including fruit and nut trees. It and the creatures it hosts might also reintroduce a soul-expanding sense of wildness, mystery, and magic. And, as we recover the vital roles of culture that were undermined by scientific rationalism this will not only enrich architecture, cities, and landscape, the plastic arts of sculpture and painting will return to their role of enhancing, even completing, buildings, not least by making their meanings more explicit as well as richer and more nuanced.

This approach to design is the antithesis of the creative license celebrating the individual creative ego that has characterized much recent architecture. Weaving relationships requires manners, respect for and the establishment of synergistic reciprocities with what is around. But too many contemporary buildings—icons, parametric blobs and other forms of disruptive asshole architecture—bereft of manners flaunt themselves arrogantly as sunset effect caricatures of the worst pathologies of modernity. An antidote is to design buildings of quiet presence, and creating a distinct sense of place is important too. Reweaving a web of relationships involves being attentive to the many forms of flow around. Attention will return to the skillful crafting of the most crucial of these flows, all the many forms of human circulation, by which we navigate and are enticed through the built environment to enliven and generate activities adjacent to these routes. In contrast to the fluid slosh of space found in modern or parametric layouts, reweaving requires each part to be a distinct and rooted center, as consistent with sustainability’s ambitious agenda that every place be treasured in itself as an essential part of our precious planet.

If reweaving is about creating a rich web of horizontal relationships, these need to be stabilized and grounded by creating vertical connections with earth and sky, past memories and future potentials, as well as in our psyches, in the depths of our souls, and with our aspirant spirit. The goal is nothing less than to create a world where citizens are encouraged to live full and, most important of all, deeply satisfied lives. If proposals do not also promise to interrelate as part of a larger whole, and offer an expanded and deepened sense of fulfilment, they will not be enthusiastically embraced and implemented. Instead of the frustrations of half-lived lives, citizens will then be able to look back from their deathbeds at lives rich in enlivening experiences and deep connections to people and places. What an ennobling agenda for architecture! And what an exciting time to be an architect, participating in the great adventure of our time.

Overgrowth is a collaboration between e-flux Architecture and the Oslo Architecture Triennale within the context of its 2019 edition, and is supported by the Nordic Culture Fond and the Nordic Culture Point.

.jpg,1600)

.jpg,1600)