The Indians were many and would replenish every hour … they could not have been more than a stone’s throw away when more than four hundred Indians approached from water and land … charging against us from time to time, following us all night, to the point of not letting us make repairs at a certain moment, because they were ahead of us. Thus it went until dawn, when we found ourselves in the midst of many and very large populations, from where fresh Indians would emerge so that those who were tired could remain … it took us so long to exit the settlement of this great Sir named Machiparo, of all [settlements we encountered] it apparently lasted more than eighty leagues, which is more than a tongue in length, all of it populated, to the point that there wasn’t between one population and the next more than a crossbow shot, and the one which was furthest was less than half a league away, and there was a village which lasted five leagues of house after house, that it was a marvel to see.

—Friar Gaspar de Carvajal, 1541–15421In the Amazon, one of the world´s fastest-growing urban frontiers, 80 percent of city growth has been in shantytowns largely unserved by established utilities and municipal transport, thus making “urbanization” and “favelization” synonymous.

—Mike Davis2

Amazonia can be described as a graveyard of modern planning ideas. Victorian industrialization provoked the first rubber boom in the Amazon between 1878–1912, the urbanization of which consolidated a riverine regional structure whose bones and sinews existed since pre-Colonial times. The trauma left behind by this period, its cruel labor relations and immense inequity that unfair exchange engendered, is still chanted today in ritual practices throughout the upper Amazon. From an infrastructural standpoint, the Madeira-Mamoré railway, also known as “Mad-Maria,” lies as a ruined symbol of the modern illusions that the rubber boom held for Amazonia. Even the genius of US industrialism, Henry Ford, failed in his attempt to establish and manage a plantation during the second and short-lived rubber boom during the interwar period. Ford’s mono-cultures were devoured by blight, and Fordlandia, the capital of Ford’s Amazonian enterprise, is currently a ruin in the Tapajos, a tangible sign of the need to redefine industrialization and modernization in the context of the forest.

The urban structure of rubber is still active in the palimpsest of Amazonia’s urbanization today. With the geopolitical goal of consolidating international borders and integrating remote forests into national territories, the Cold War military dictatorships of Brazil and other Latin American countries pursued a development model inspired by postwar economist François Perroux’s idea of “growth poles.” This demanded the deployment of infrastructures—specifically highways and hydroelectric plants to service mining, other extractivist activities, and cities—and “rational planning” whose geometries were modeled upon natural resource satellite surveys. Governments promoted the colonization of the Amazon as a way of “opening land without people to the people without land.” Amazonia, though, was not an empty land, and as ranchers and farmers started to deforest it in order to claim the cleared lands, they encountered indigenous groups, quilombolas, rubber tapers, Brazil-nut gatherers, and other forest peoples. Conflicts over land remain one of the most intractable effects of opening up Amazonia.

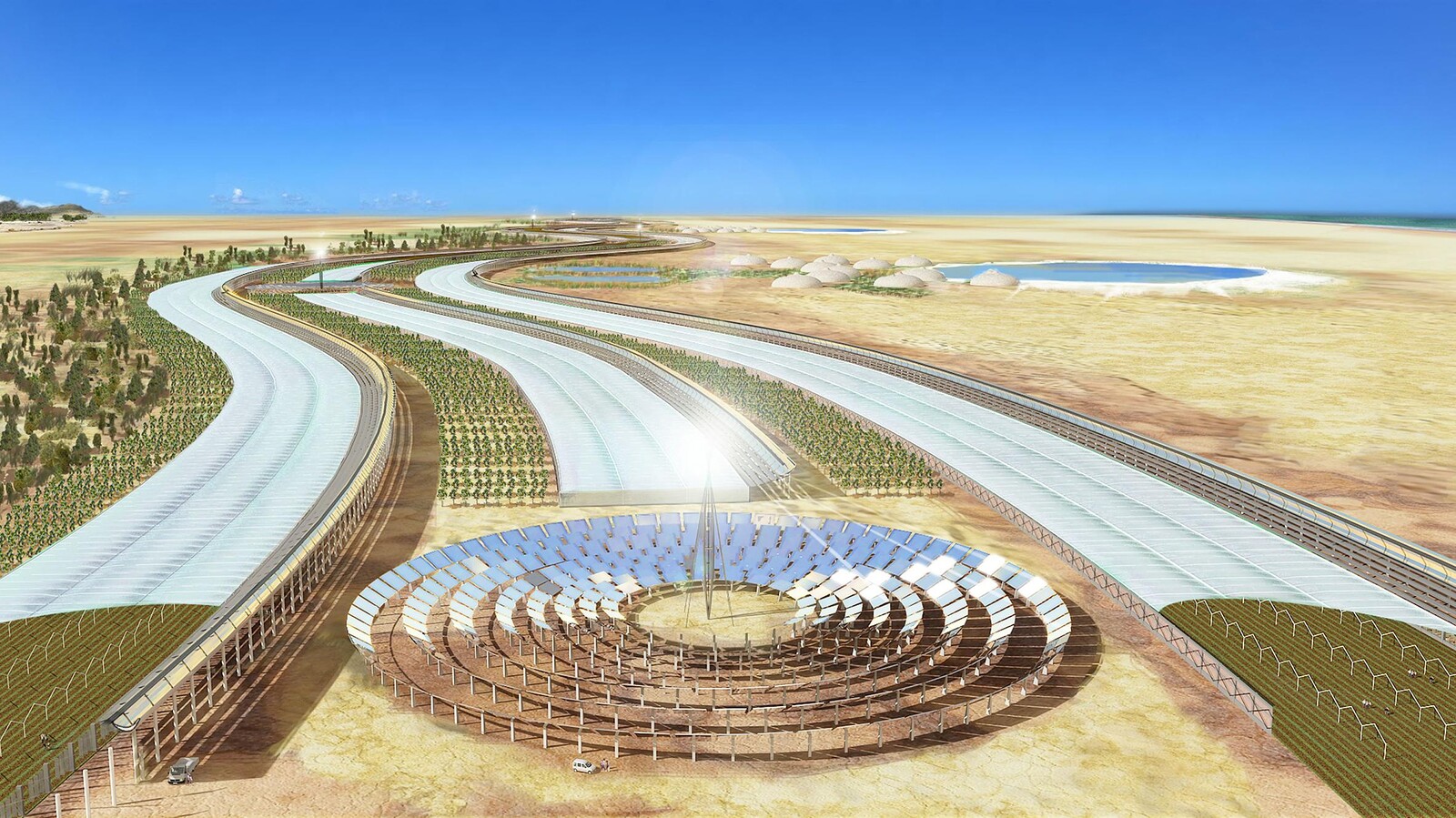

The Integration of the Regional Infrastructure of South America (IIRSA), now South American Infrastructure and Planning Council (COSIPLAN), was launched in 2000, and has effectively unleashed a new wave of urbanization and infrastructure development projects across the continent. It proposes to link Atlantic economies to Pacific ports with cross-continental highways, railways, and other multi-modal mechanisms, as well as to expand the energy grid through the deployment of mega hydro-electric plants.3 This project ignores the graveyard of failures in Amazonia and is destined to let loose uncontrollable forces of ruin once again.

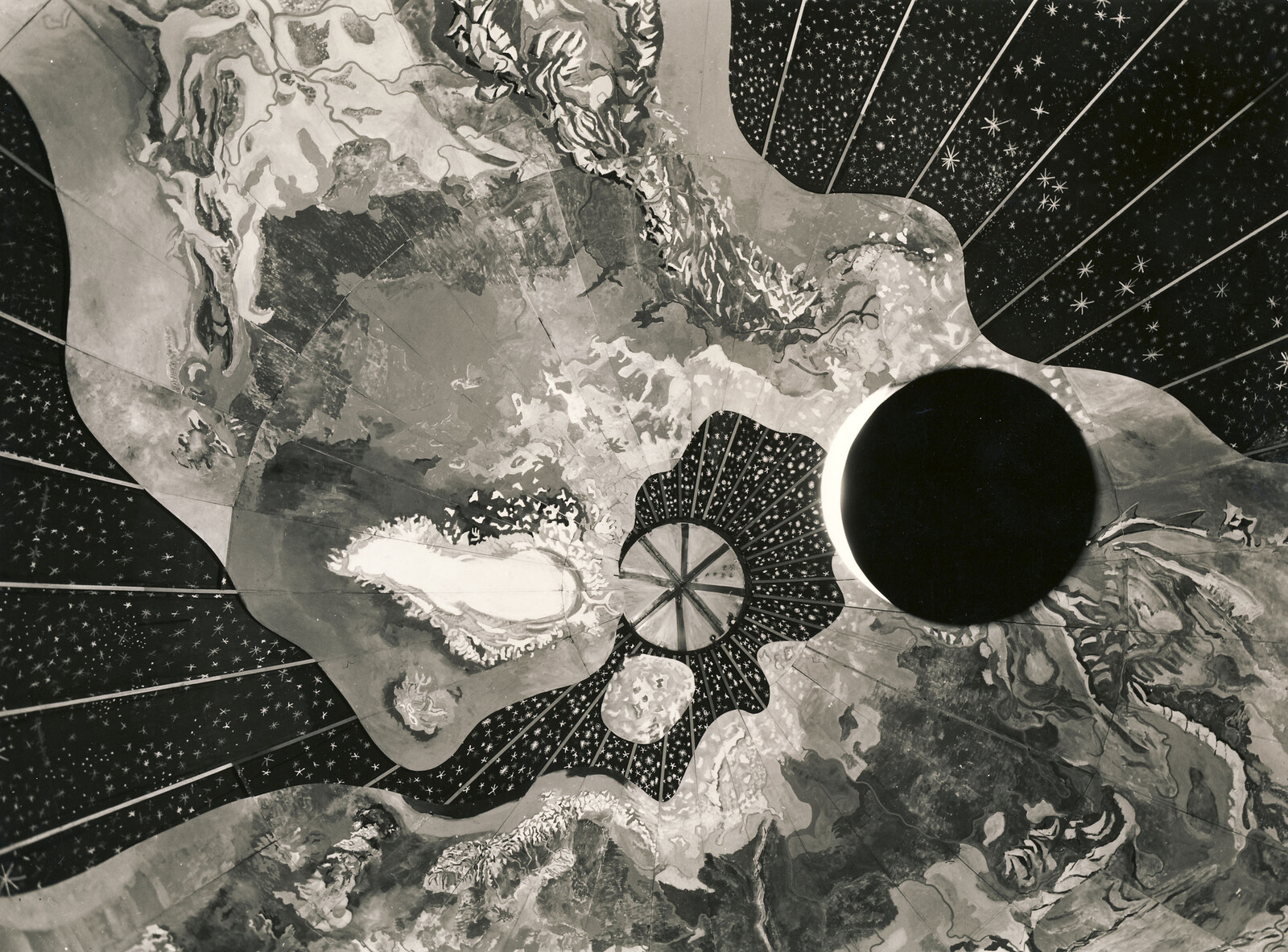

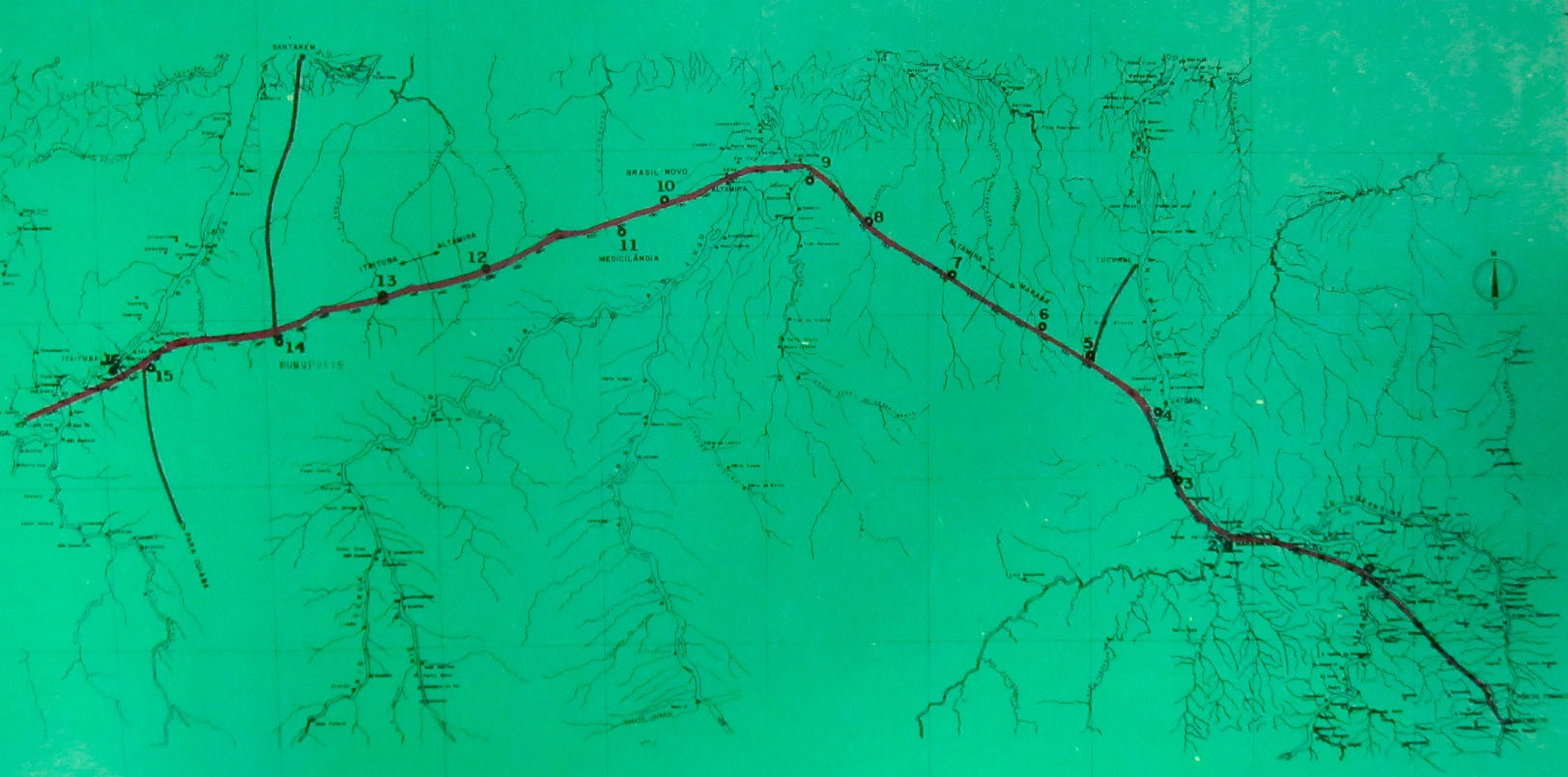

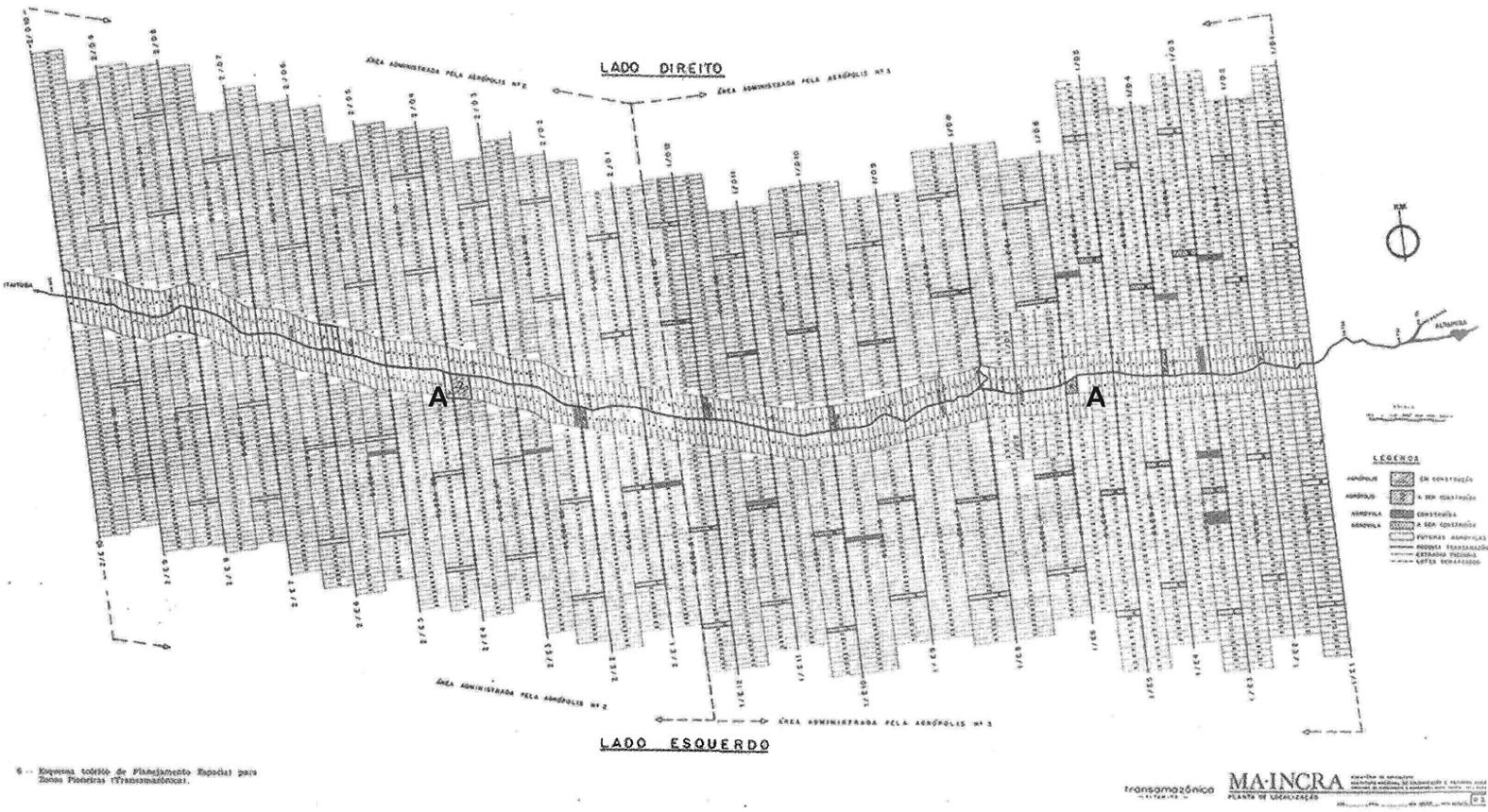

New towns along the Transamazonian highway, between Estreito (far right) and Itaituba (far left). Source: Rego (2017), Camargo (1973).

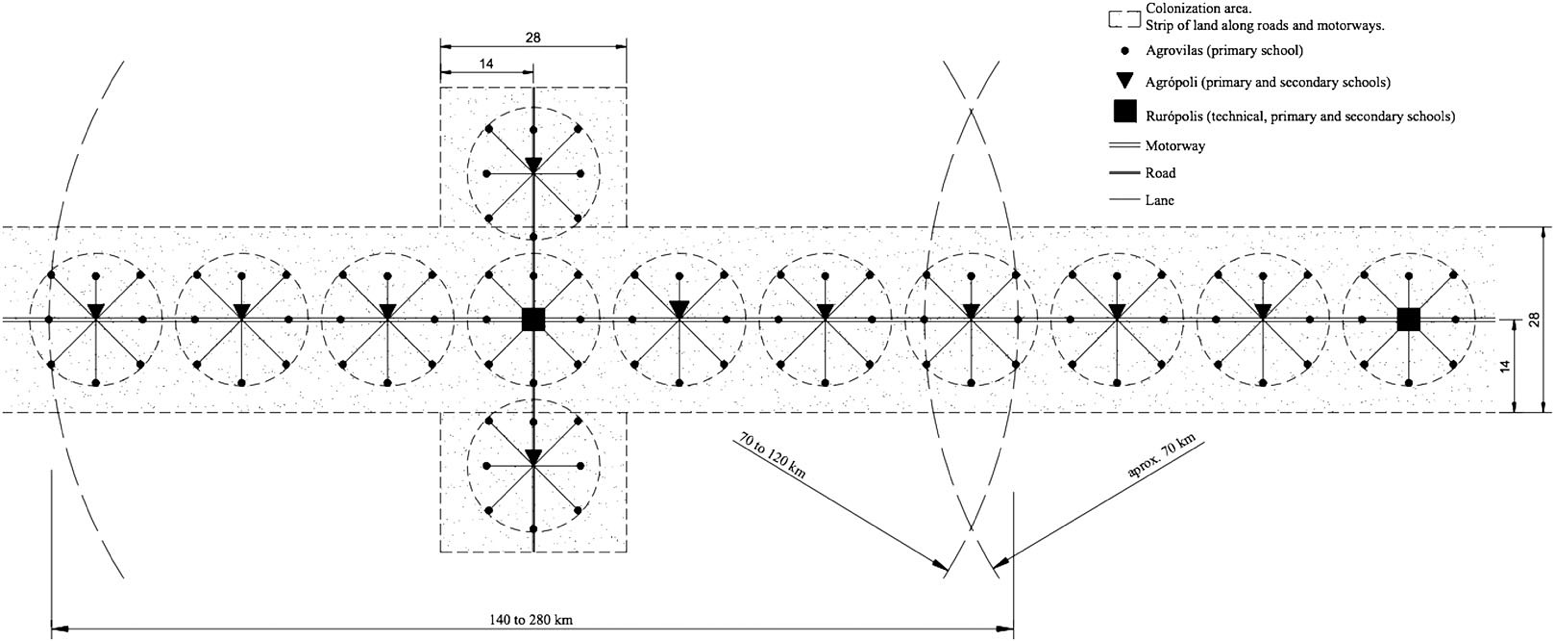

Urbanismo Rural planning scheme for the Transamazonian highway. Source: Rego (2017), Camargo (1973). Adapted by Rego (2017).

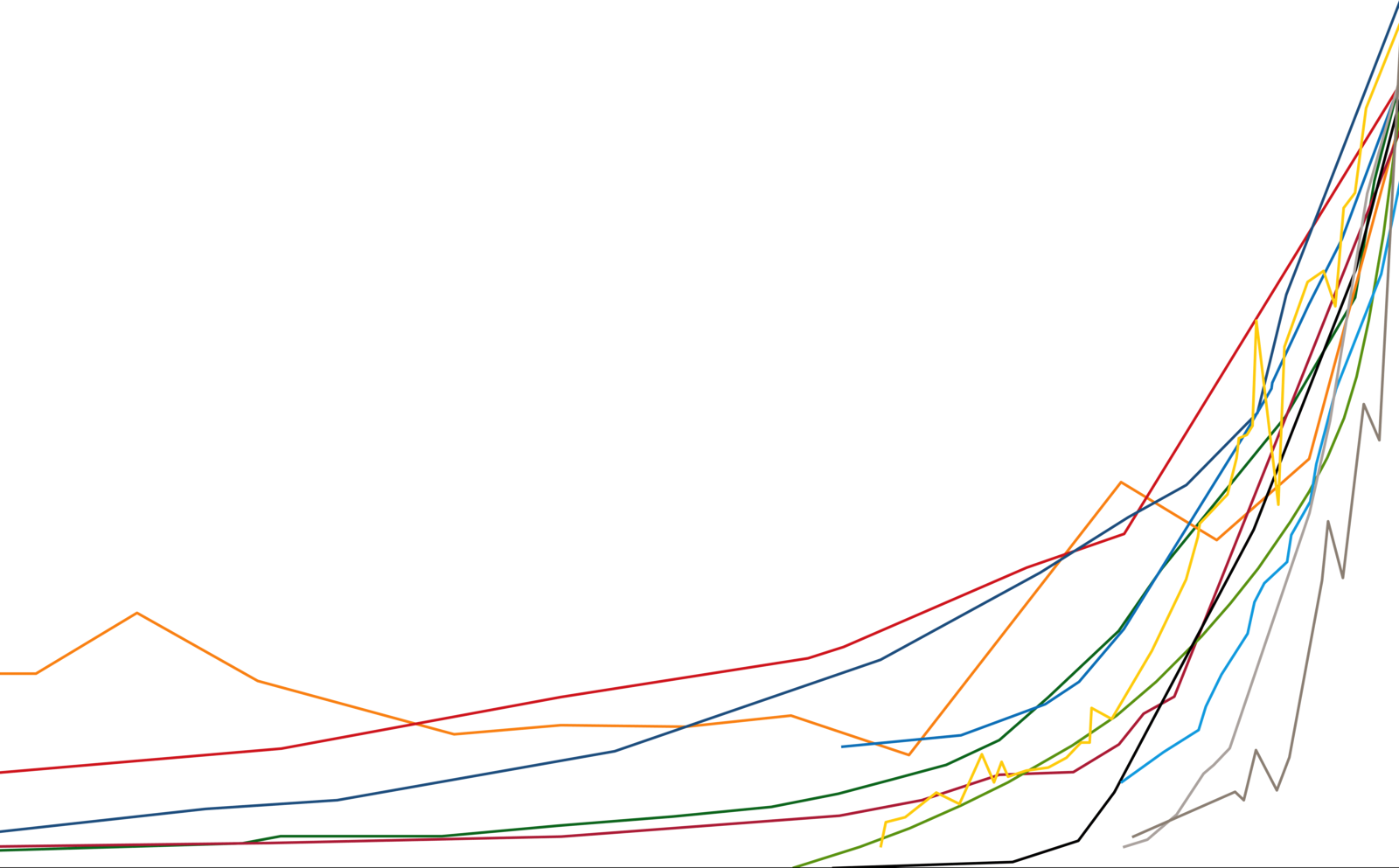

Linear land subdivision along the Transamazonian highway. Source: Rego (2017), INCRA (1971).

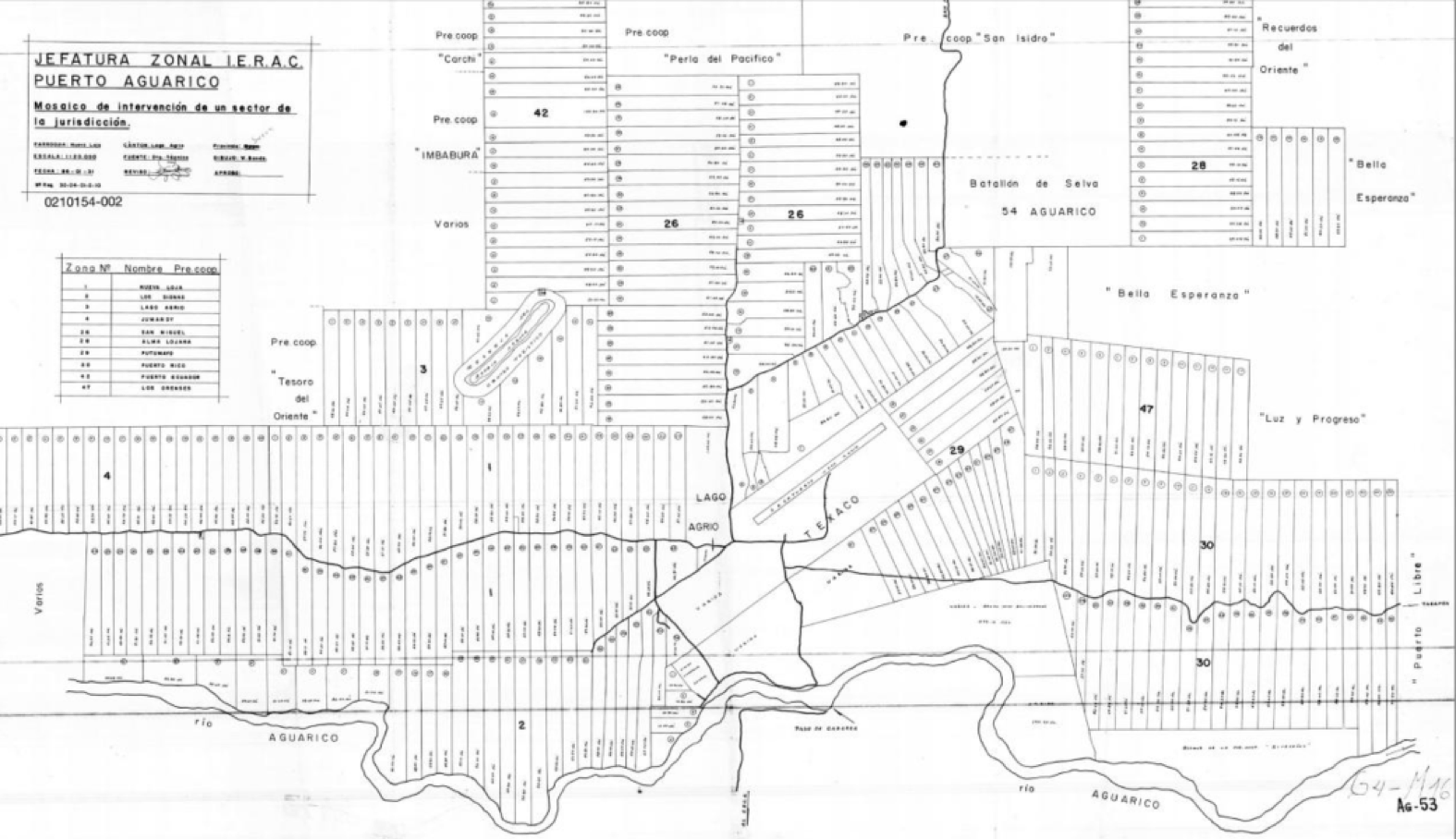

Land strips in Ecuadorian Amazon, Jefatura zonal IERAC, Puerto Aguarico, 1986. Source: Del Hierro (2017), IERAC.

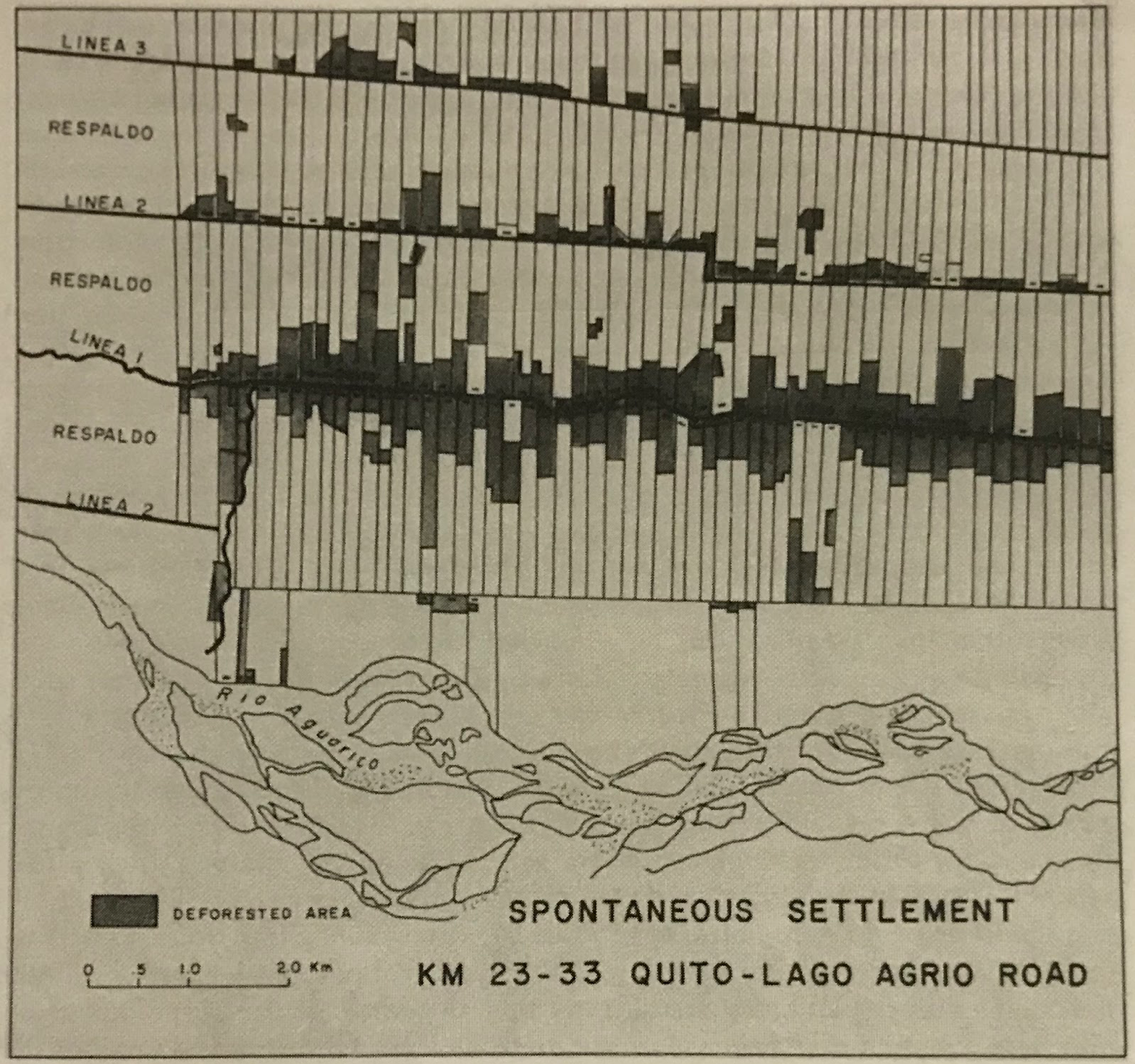

The spontaneous pattern of development described by Hiraoka et al. Elongated IERAC-style patterns of land subdivision emerge alongside trails and roads. Further out, two secondary arteries emerge, with only one plot of land accessible from them. The second and third tiers are known as retiros. Hiraoka considers this and extremely inefficient system of land subdivision. On outcome of the elongated plot of land is that it did not support cattle ranching due to its shape. Source: Hiraoka et al. (1980).

New towns along the Transamazonian highway, between Estreito (far right) and Itaituba (far left). Source: Rego (2017), Camargo (1973).

Why has planning for modernization in Amazonia failed so miserably? Amazonia is a very dynamic, shifting realm of water and life that includes human societies. What would it look like if South American governments derived design inspiration from local Amazonian conditions and indigenous knowledge for its next wave of planning? Brazilian extractive reserves constitute a prime example of how the forest can be harvested sustainably while providing an economy for its people. Indeed, most Amazonian communities cultivate, harvest and manage gardens (chakras) and the forest at large within an agricultural ontology that radically differs from a technocratic understanding of agriculture. Agriculture, and settlement more widely in Amazonia needs to be conceived and promoted as polyculture or as productive forest. From an architectural and settlement standpoint, key principles of Amazonian design should to be promoted: floating (the balsa), tensile (the hammock), tip-toeing (the piloti), land-forming (mounds, weirs, chinampas, and other green-infrastructures conceived through indigenous “bio-engineering”), communing, and so forth. Only when we start learning from Amazonians will the graveyard of ideas that is Amazonian planning stop piling up.

The Añangu: A Case Study

The Ecuadorian Amazon remained relatively unaltered until the end of the 1960s. Indigenous communities subsisted up until then on shifting agriculture (rotating chakras), hunting, and fishing. This relative isolation was lost when oil was discovered in 1967 by the Texaco-Gulf consortium in what is today the city of Lago Agrio. Oil exploration went hand in hand with plans that the Ecuadorian government, through its Institute for Agrarian Reform and Colonization, had for the region. With governmental consent, incentive, and collaboration, oil companies built infrastructure such as roads, highways, airports, company headquarters, oil wells, and unlined oil pits. The government requested oil companies to build more roads than were needed for the extraction operations with the purpose of fulfilling its plan, devised in 1969, to populate the Ecuadorian Amazon. Oil discovery in the Ecuadorian Amazon triggered the formation of what could be termed the “oil axis” of urban development with Lago Agrio as its northernmost primary node, with secondary nodes in Aguarico, Sacha, Shushufindi, Auca, Yuca, and Atacapi.

In this context of agrarian reform, colonization, extraction, and urbanization, indigenous communities felt their livelihoods and lands were under threat. In 1972, the ECUARUNARI indigenous movement was created in the Andean comuna of Tepeyac with a central objective of consolidating access to land through legalization. In 1986, ECUARUNARI joined with the Confederation of Indigenous Nationalities of the Ecuadorian Amazon (CONFENIAE) and other smaller movements to form a national association, the Confederation of Indigenous Nationalities of Ecuador (CONAIE). CONAIE’s ablility to more strongly leverage legal land claims led the Ecuadorean government to recognize the presence of Amazonian communities and their rights to ancestral lands, or to lands which they had evidently settled before their colonization.

The Ecuadorian government maintained exclusive rights of access to minerals and fossil fuels located underground. It also set conditions on the use of the natural resources located within the legal boundaries of indigenous territory: communities had to pursue a “traditional” management scheme that prohibited “indiscriminate” logging, hunting, and fishing. In addition, rights of access to water routes became the prerogative of the state. Thanks in part to the access routes that the oil industry had built into the formerly inaccessible interior, tourism became a viable enterprise to be developed in alliance with environmental and conservation movements. In some instances, exploitative arrangements were established between tourism agencies and indigenous communities, whose members served as cheap labor, whose hard-earned communal lands were often leased on predatory terms, or whose culture was commodified and performed for the satisfaction of foreign expectations.

The Añangu Kichwa commune of the Napo Runa ethnic group broke the mold in the way they have adapted to a new wave of hyper-globalization. They have established five successful programs along the Napo river within the Yasuní National Park by “communing into” the global capitalist system through turismo comunitario (community-based tourism), cultural vindication, and female empowerment. What started in 1998 as a humble community-owned tourism venue of four cabañas has since grown into a tripartite communal enterprise composed of a luxurious and expensive resort (Napo Wildlife Center), a community-based compound located in the comuna (Napo Cultural Center), and a camping area for the more adventurous on the fringe of the Napo territory. The communal enterprise was triggered in tandem and with the support of Tropical Nature, an NGO promoting conservation through ecotourism in Latin America. Projects derived from this type of association often fail in the long-term because the communities often become dependent on the NGOs. This was not the case with the Añangu, who dismantled their partnership with the Tropical Nature in 2007 and have been successful managing their initiative ever since.

The Añangu’s communal tourism enterprise is not the only one in Ecuador, where the state, through its Ministry of Tourism, has incentivized the development of community-based and owned rural, ecological, and cultural tourism. But it is probably one of the most successful from the point of view of self-determination and cultural vindication. For the Añangu, tourism has been a tool for the preservation of an ancestral culture that they deeply value, as well as a mechanism for the defense of the jungle in the face of what many indigenous communities consider state-sponsored, destructive, un-reciprocal practices of agri-business and mineral/oil extraction. For the Añangu, eco-tourism seems to have become not a source for cultural alienation but a form of resistance against national and global forces they perceive as threats to their social reproduction. This resistance has been achieved through a thorough integration into the global market of eco-tourism, yet on their own terms and considering the demands of those who wish to consume their forest and their culture. This adversarial “integration” is the key to their success. Communities who have passively accepted, for example, the “social contract” of oil corporations in the Ecuadorian Amazon have traded their ancestral cultures for alcohol, weapons, and excess.4

Why have the Añangu been so successful at integrating themselves, through resistance, into national and international market circuits without surrendering their ancestral knowledge and customs? What have their strategies been? What are their ultimate objectives? Several traits come to mind as potential underlying sources for their prosperity, and present the Añangu way of life as an exemplary model for sustainable development in Amazonia:

1. The Añangu have developed alliances with international actors and continuously seek cross-cultural encounters.

2. They have used their cultural traits as a pathway towards empowerment, not merely as a performative or superficial commodity.

3. They have built decision-making upon deeply rooted participatory processes of consultation (asamblea) in order to develop their own forms of local institutions, with local laws, rules, and regulations (all within the larger framework of national law). In a community of approximately 188 individuals, nearly 70 adult members (socios) participate on a monthly basis in the assembly meetings, where rules and other matters get decided upon. Mingas, a form of collective labor, have also persevered, with working relations based on reciprocity, cooperation, and mutual benefit.

4. Communal ownership of land has not led to a tragedy of the commons, but rather an instance of the indigenous utopia known among the Kichwa as Sumak Kawsay, a concept of good living in harmony with nature that the Ecuadorian state borrowed for its 2008 Constitution without truly comprehending its ontology. The logic of a commons as applied to the land and its resources by the Añangu has been transferred to ownership of financial resources. The community holds a bank account under its name, and checks cannot be emitted without the knowledge and approval of community members. The Registro Unico de Contribuyentes (RUC, a tax identification number) is also under the collective identity of the community. The Añangu pay taxes as a collectivity and manage their finances collectively.

5. The role played by women is central to their empowerment and to the empowerment of the community at large. The Añangu, under collective agreement, banned alcohol in their territory (all rules apply also to visitors) in order to eliminate domestic violence, a trait that the adults recollect as having been introduced by alcohol into their communities. Furthermore, women have organized themselves into the Mamakunas Organization, a cooperative devoted to Kichwa arts and crafts produced for Kuri Muyu, the Añangu souvenir store.

6. The community is not a product to be sold by an eco-tourism agency. The Añangu choose how to represent themselves, and share their culture and rituals with others as a means to preserving them.

7. Because Añangu workers are also the owners of the communal tourism enterprise, service areas are well designed and differ only slightly from the “served” areas. This spatial and architectural pattern is atypical in Ecuador and other Andean countries, which is characterized by immense spatial inequity, even at the scale of the home.

8. The Añangu understand and have incorporated modern infrastructures into their settlement and tourism venues. With the help of an engineer, they have built a water treatment plant and have installed a Wi-Fi antenna. They are planning to incorporate clean energy generation.

9. The Añangu have chosen the education of their children and youth as one of their main collective investments. They have fought to guarantee that their school is bilingual (Kichwa and Spanish). In collaboration with a group of students from an architecture school in Nebraska, they developed a design for their local school based on their vernacular architecture and the use of local materials. They presented the proposal to the Ministry of Education and were able to construct it instead of the barrack-like structures that are generally provided for public schools in rural areas. The Añangu also engage in the development of the educational curriculum and incorporate oral traditions into it. Students of all ages also learn English thanks to a volunteer program they have in place. Last but not least, the Añangu deposit the profits of their tourism enterprise into a Caja de Ahorros (Community Savings Bank) which serves, among other purposes, to finance the costs of higher education for their youth.

10. The Añangu are planners. They are currently planning to develop a forest regeneration project in collaboration with affiliated communities of the Ecuadorian Amazon. As in all aspects of their cultural life, they are proposing to design forest remediation along the lines of polyculture, the traditional mode of agriculture in the Amazon. Besides recuperating ecologies, this would allow them and other communities to provide food, construction materials, and medicinal plants for themselves and their visitors, and possibly even export forest products to international markets.

Towards Symbiosis

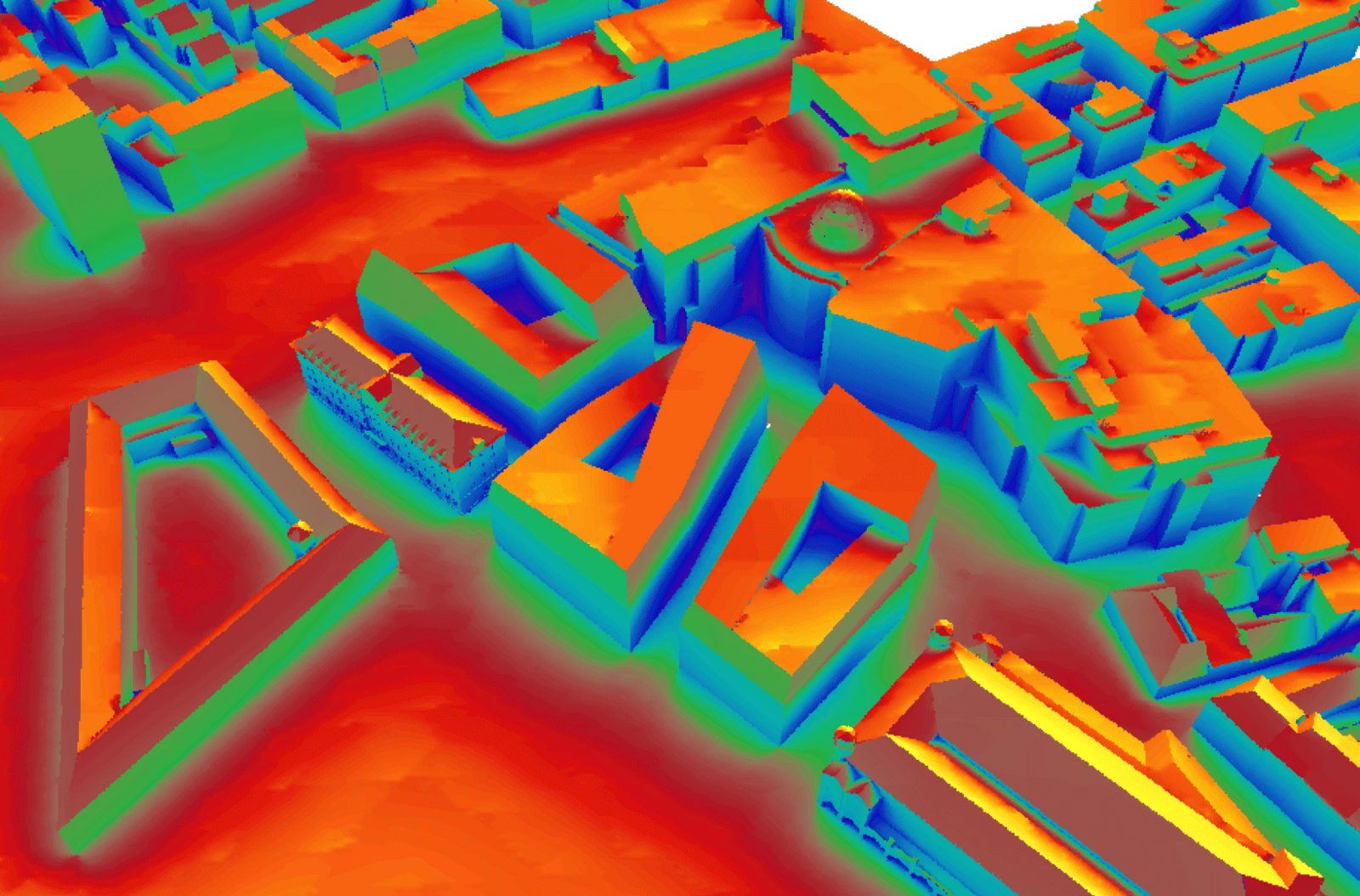

The relationship between culture and nature among indigenous populations of Amazonia was and is symbiotic, to the point that the word rainforest acquires a new meaning, as partially constructed or anthropogenic, useful, purposefully productive “wilderness.” The pristine forests of the Amazon, as epitomized by the romanticized and exoticized imaginary of the Enlightenment, are being redefined as strongly managed landscapes. This process can be referred to as “the ‘domestication of landscape;’ the ‘conscious process by which human manipulation of the landscape results in changes in landscape ecology and the demographics of its plant and animal populations, resulting in a landscape more productive and congenial for humans.”5 Furthermore, recent archeological research has unveiled a positive correlation between “periods of landscape stability and soil formation” and “periods of high population,” while the opposite seems to be the case for traditionally Western, industrial agri-business, where high population rates tend to be accompanied by high rates of erosion.6 A critical element in recuperating and renewing this relationship is to understand that agricultural functions are intertwined with, rather than segregated from, with pre-Hispanic settlements.

Many indigenous communities in the Ecuadorian Amazon have resisted the advance of resource frontiers by advocating for the legal recognition of their right to their ancestral lands under the figure of “indigenous territories,” a communal form of land tenure. Commune-based lands, they argue, allow indigenous groups to collectively manage their natural resources in a sustainable manner, whereas the fragmentation of the forest under private models of “lotización” (an urban plot style of land subdivision) leads to fragmentation and ecological disruption. This commune system, in spite of its evident environmental and social benefits, is under threat by policies that exclude it from public services, which are reserved for areas categorized as “urban” and offered exclusively to lands that fall within jurisdictions of municipalities. Communes are not considered “urban” and remain under the umbrella of the Ministry of Agriculture or, if located within a protected area, under the Ministry of the Environment. If policies that extend public services to rural and forested areas are not put in place, governments will continue to promote the fragmentation and peri-urbanization of Amazonia.7

Urbanists are awakening to the positive, constructive relationship that is possible in the Amazon. The future of half of the Earth’s remaining rainforest may depend on our ability to re-conceptualize it as a productive forest. Indigenous groups who have managed to thrive in the midst of immense pressure to enclose their labor and lands, such as the Añangu, tend to be those who resist abdicating ancestral cultural practices and communal forms of land management, land tenure, indigenous law, self-governance, and collective labor. Conservation, by demarcating untouchable areas, implicitly leaves everything else open for destruction. This demarcation is dangerous in the face of immense pressure by oil extraction and mining companies, agri-business (particularly soy bean and palm tree plantations), and ranching—all export driven global market commodities. The Amazon is a responsibility for the future to be addressed from the perspectives of both supply and demand. An understanding of ancestral modes of resource management, agriculture, and settlement patterning may guide us towards establishing a sustainable future, not for the cities the forest sustains, but for the very forest that cities may steward, and not deplete, as in ancient times.

José Toribio Medina, Descubrimiento del río de las Amazonas: según la relación hasta ahora inédita de Fr. Gaspar de Carvajal con otros documentos referentes a Francisco de Orellana y sus compañeros (Seville: E. Rasco, 1894)

Mike Davis, Planet of Slums, (London and New York: Verso, 2006).

The planned expansion of the energy grid is largely in order to serve higher degrees of mineral and fossil-fuel extraction, as well as mechanized agriculture.

The scope of this paper does not allow me to cover the case of some Huaorani communities who have slipped from indigenous to indigent in the Repsol-YPF oil block under the “social responsibility” aegis of the petrol enterprise.

Michael Heckenberger and Eduardo Góes Neves, “Amazonian archaeology,” Annual Review of Anthropology 38.1 (2009): 251–266.

Verónica Pérez Rodríguez, Kirk C. Anderson, and Margaret K. Neff, “The Cerro Jazmín Archaeological Project: Investigating prehispanic urbanism and itsenvironmental impact in the Mixteca Alta, Oaxaca, Mexico,” Journal of Field Archaeology vol. 36, no. 2 (2011), 96, ➝

The servicing of these areas could follow off-the-grid and cost-effective strategies for energy and water provision, as well as waste management. Alternative technologies are not only environmentally friendly, but also economically feasible.

Overgrowth is a collaboration between e-flux Architecture and the Oslo Architecture Triennale within the context of its 2019 edition, and is supported by the Nordic Culture Fond and the Nordic Culture Point.

Category

Subject

This article would not have been written without the guidance of UCLA professors Susanna Hecht and Helga Leitner, and without the generous contribution of Jiovanny Rivadeneira, Ñuka Punlla, Gabriel Moyer-Pérez, Paula Izurieta, Arturo Mejía, and the welcoming Añangu community whose achievements restore hope in the future of Amazonia. I was able to visit the Añangu community in the summer of 2017 thanks to a Tinker Foundation Field Research Grant endowed through the UCLA Latin American Institute.

Overgrowth is a collaboration between e-flux Architecture and the Oslo Architecture Triennale within the context of its 2019 edition.

.jpg,1600)

.jpg,1600)