Who can pick up the weight of Britain,

Who can move the German load

Or say to French, here is France again?

Imago. Imago. Imago.

—Wallace Stevens

1.

Canadian director Mary Harron shot the influential film American Psycho (2000) in downtown Toronto in 1999. She also co-wrote the script, with actress and filmmaker Guinevere Turner, based on Bret Easton Ellis’s 1991 book of the same name. The controversial novel, while critically acclaimed, had ignited a moral panic in North America because of its misogyny and detailed descriptions of sexual violence. Both film and novel are set in Manhattan and follow the first-person narration of Patrick Bateman, an investment banker who happens to be a serial killer.

Or maybe not. One ongoing critical discussion about American Psycho is whether the murders actually happen, or, instead, are simply hallucinations inside Bateman’s head. He can’t recall how many people he’s killed. Is it twenty? Or forty? While the camera’s viewpoint and the voiceover narration ask us to side with Bateman, there are reasons to doubt his account. The so-called killings don’t interrupt the behaviors of the other characters in the film. And then an ATM machine orders him to feed it a stray cat. As the film progresses, the viewer’s experience mirrors Bateman’s. Bateman debates what is real about reality; the viewer questions what is real about fiction.

Harron and Turner’s script delights in exploring these confusions between fiction and reality. Architecture, décor, and artifacts—simultaneously material and immaterial—are all up for grabs. The film’s climax, for example, involves iconic Toronto commercial real estate: the Toronto-Dominion (TD) Centre. Designed by Mies van der Rohe, it officially opened in 1967 and features two almost identical towers, 55-storeys and 44-storeys, and a one-storey banking pavilion. Various architects added additional towers until 1992. Along with Toronto City Hall, it marks both the city’s skyline and its imago—the almost-unconscious mental image Torontonians have of their own city. In 2007, the Royal Architectural Institute of Canada declared it a masterpiece of the twentieth century. Yet the film takes place in Manhattan. How could an architecture so closely identified with Toronto so easily double for somewhere else onscreen? The explanation combines film technique and… something else. It’s worth quoting Harron at length. She explains:

The one scene where we really did have to use Toronto for New York is the big kind of climax of the movie, when he’s in a panic and he runs to his office. And they [the production team] suggested shooting in the Toronto-Dominion Centre, which is these two identical towers in a plaza. Really beautiful architecture, Mies van der Rohe, and sort of classic, beautiful modernism. And the idea of the identical towers was so great because the story itself has a lot of doubling. It’s about mistaken identity.

The first big murder you see Bateman commit is of his rival, Paul Allen, that he’s obsessed with, and he’s someone who’s very very like him, and so people always are confusing him for someone else. So the whole idea of the mistaken identity is in the towers, because he runs into one thinking it’s his office, and it’s not. And he ends up shooting a guard, and then he runs across the plaza to the other identical tower, where he finally makes a confession to his lawyer.1

Harron here riffs on the genericness of the modern office building. Given the influence of Miesian architecture across North American cities, the TD Centre is just like office buildings elsewhere. These office towers are so much alike we all might run into the wrong one by mistake. At the same time, these two near-identical office buildings are signature Canadian landmarks by one of the most acclaimed architects of the last century. How can they be generic? And again, how can twin Toronto icons be mistaken for buildings in Manhattan? For Harron’s team, the dilemma became a chance to deepen the film’s exploration of ambiguity. They exploited the interplay between the psychic role of the office buildings in Toronto—the fiction of architecture—and the array of technical tools available to a savvy filmmaker and her collaborators—the reality of film. Harron explains further:

One of the things that the DP [director of photography] Andrzej Sekuła did was—we did a matte. We did an old-fashioned film trick as he runs across the plaza, of doing very slow film so that the towers would look very bright. So we had … the lights of the skyscrapers coming out, and then we matched that—matted it in—with Bateman running across the plaza.

And the other thing that happens in that scene is he actually runs from Toronto—Toronto Dominion Plaza—around the corner, and then he’s in New York, because we had to shoot that bit in Wall Street.

Real life invaginates the contradiction of real and perceived. Through architecture, a building in Toronto copies a building in Manhattan. Through architecture, one building is mistaken for another. Through cinema, Toronto doubles for Manhattan. Toronto’s signature architecture proves generic. And yet, that genericness somehow also becomes Toronto’s identity.

2.

American Psycho explodes identity. It explores how unstable and unmoored our identities can be; first, our individual self-identities; then our mental images of others; then, the physical environments and objects which we take to both reflect and embody who we are. Turns out they don’t. Or as American poet Wallace Stevens taught us, the imagination—the fiction—evades all attempts to moor it to the empirical: “Imago. Imago. Imago.”

It’s cliché to say that Toronto’s collective identity, its imago, is an anxiety about Toronto’s collective identity. This angst surfaces as a question about whether Toronto is a world-class city. It pervades discussions about the city’s quality of life, crossing over from cultural capital to economic development to the volatile real-estate market. Last February, the Royal Bank of Canada pronounced that Toronto was the most expensive real-estate market in Canada. Toronto had with a benchmark price for a home of CAN$1.26 million, significantly higher than New York City. (The national average in Canada is less than half of that.) While experts say that the frenzy is over and the price bubble has burst, Toronto’s brand—its imago—now includes the unaffordability of its real estate.

Anxiety about real estate is also a theme in American Psycho. In another iconic scene, Bateman dons a dust respirator mask before entering his rival’s apartment, expecting to see walls spattered with blood and the mutilated corpses of women, including one he murdered with a chainsaw. To his surprise, he is met by Mrs. Wolfe, a real estate agent who is selling a perfectly clean, freshly painted, blood-free apartment. Either Bateman hallucinated the murders, or the real estate agent is even more psychotic than he is. Is Mrs. Wolfe ready to cover up murder and move corpses in order to move real estate? The scene doesn’t register a confusion between Manhattan and Toronto (the apartment was a set), but it does re-emphasize that the identity of people and places are fungible.2

Bateman’s fantasies are intimately bound up with how design brands us, how we as consumers build an identity out of affiliations to designed objects. These affiliations work on a different level than our appreciation of design as connoisseurs. Early on, Bateman kills a colleague with an axe because he envied his colleague’s business card. In a memorable scene—known to cinema aficionados as the business card scene—Bateman’s inner voice, “cold with hatred,” implores the viewer in a voice over: “Look at that subtle off-white coloring. The tasteful thickness of it. Oh my God, it even has a watermark.” The visual joke is that all the business cards in the scene look alike.3 Like the TD Centre’s two “identical” towers, we might mistake Bateman’s business card for his rival’s. The film underscores design as a narcissism of small differences.

The Toronto Dominion Centre, 1974. Photo courtesy of the Panda Associates fonds, Canadian Architectural Archives, Archives and Special Collections, University of Calgary, PAN 74256-4c, 262A/99.01.

3.

Toronto was an odd, even controversial choice for the film shoot. During production, the movie’s plot was uncannily in tune with the newspaper headlines, mirroring film, real estate, and real life. The week filming started, the “Noteworthy” column on the front page of the Toronto newspaper The Globe and Mail set a notice about the film industry and a notice about real estate industry side-by-side:

Victims’-rights groups are lobbying to prevent the filming of American Psycho in Toronto, but the film’s director, Mary Harron, says her movie about a serial killer will not be particularly violent.

A Globe and Mail exclusive ranks communities across Canada by highest average house price. The winner: A subdivision of Vancouver surrounding the University of British Columbia. Home to fewer than 7,000 people, this area’s 2,650 dwellings are worth an average of $754,000 each.4

Furthermore, when filming began in February 1999, the front pages featured stories about a twenty-six-year-old woman who had recently pleaded guilty to charges of trying to hire a contract killer from Montreal to dynamite her estranged husband and his family. And at around the same time, the Supreme Court of Canada ruled in the “No Means No” case (R. vs Ewanchuk), invalidating the concept of “implied consent” and finding the accused man guilty of sexual assault.

It also turned out that American Psycho was a favorite novel of the real-life serial killer Paul Bernardo, aka The Scarborough Rapist, who had been convicted in a Toronto courtroom just four years earlier. Partly due to the lingering effects of the Bernardo trial, the city had to address vocal citizen protests against using Toronto as a film set for a story of rape and necrophilia. Yet like Mrs. Wolfe, politicians preferred to overlook the connection to violence, instead describing the production as a boon for the burgeoning feature film industry and the promotion of Toronto as “Hollywood North.” City councillor Mario Silva, a member of Toronto’s Film Liaison Committee, which issued permits to companies shooting films in Toronto, claimed that his “fear is getting into the realm of censorship.” “Our job,” he said, “is to protect and encourage this growing [movie production] industry in Toronto.”5

4.

Film has two contrasting powers. Film transforms reality: mirrors it; reflects or refracts it; mixes it with the fantastical and the imaginary. Film makes murder, war, terrorism, hardship, and death into fun and entertainment. When we watch a film, we participate in fiction. To know what might happen, we want to see a video. Film’s double, its opposite power, is that film reveals reality: confirms and stabilizes it. Film captures or records what exists with a reliable mechanical objectivity. We turn to film to document events and actions. To know what has happened, we want to see the video.

In American Psycho, Harron plays with the tension between these two powers. But since design and architecture are key components of that play, the tension never resolves—and certainly not by setting buildings—the real estate—as the objective real. The engagement of architecture and film raises a cascading, spiraling series of theoretical and terminological questions. Problems with words. Real Image. Virtual image. Reality. Realty. Real estate. Set. Movie set. Fiction. Doubles and doubling. Imagination. Screen. Screening. Perception. Representation. Images. Real image. Virtual image. And so we spiral on.

This spiraling doesn’t perplex us in the experience of architecture or the experience of film; we are not confused when we inhabit a building or watch a screen. But there is a reason for this: what makes those experiences meaningful is tied up in the delight we can have when we are fooled. We like make-believe. It is precisely our inability to pin down the fictional onto the real that constitutes meaning. The real image mirrors the image of the real.

What is the “real” in the “real estate”? Is a building also real estate? Note that architects, geographers, and urbanists tend to use the word “place” instead of “real estate.” The difference between the two chiefly is that place is grounded in the physical, while real estate is grounded in fiction. Place escapes capital; real estate hoards it. After all, Toronto and Manhattan are strikingly different cities; no one would mistake one place for the other. Harron explains:

When we were in prep on American Psycho, the idea came up that we should shoot in Toronto because it’s cheaper. And I said to them, I’m from Toronto and I live in New York, and I can tell you that the two cities do not look alike. Toronto is all peaked roofs, and it’s red brick and it’s spread out, it has ravines and it doesn’t have the high rise, the density, the feel of New York in any way. So they said, well, that’s too bad, because we’re going to shoot there anyway because it’s cheaper.

The “Toronto” that we put together—that we construct when we make a film in Toronto about somewhere else—contributes to Toronto’s identity. Together the film American Psycho and the filming of the film—real estate, architecture, cinema, and violence—allow us to think about the complicated ways real fictions and fiction as reality overlap in the construction of an idealized mental image, an imago, of Toronto. Who can say to Toronto: here is Toronto, again?

See Mary Harron video interview on Impostor Cities, ➝.

For an overview of the locations used in filming, see Sean Clark, “Horror’s Hallowed Grounds: American Psycho,” Bloody Disgusting, October 6, 2010, ➝.

Mary Harron discusses the scene in Mekado Murphy, “Anatomy of a Scene | ‘American Psycho,’” New York Times, Mekado June 2, 2016, ➝.

“Noteworthy,” The Globe and Mail, 19 February 1999, A1.

Leah McLaren, “American Psycho under siege: Film about serial killer won’t be ghastly, director says,” The Globe and Mail, 19 February 1999, D1.

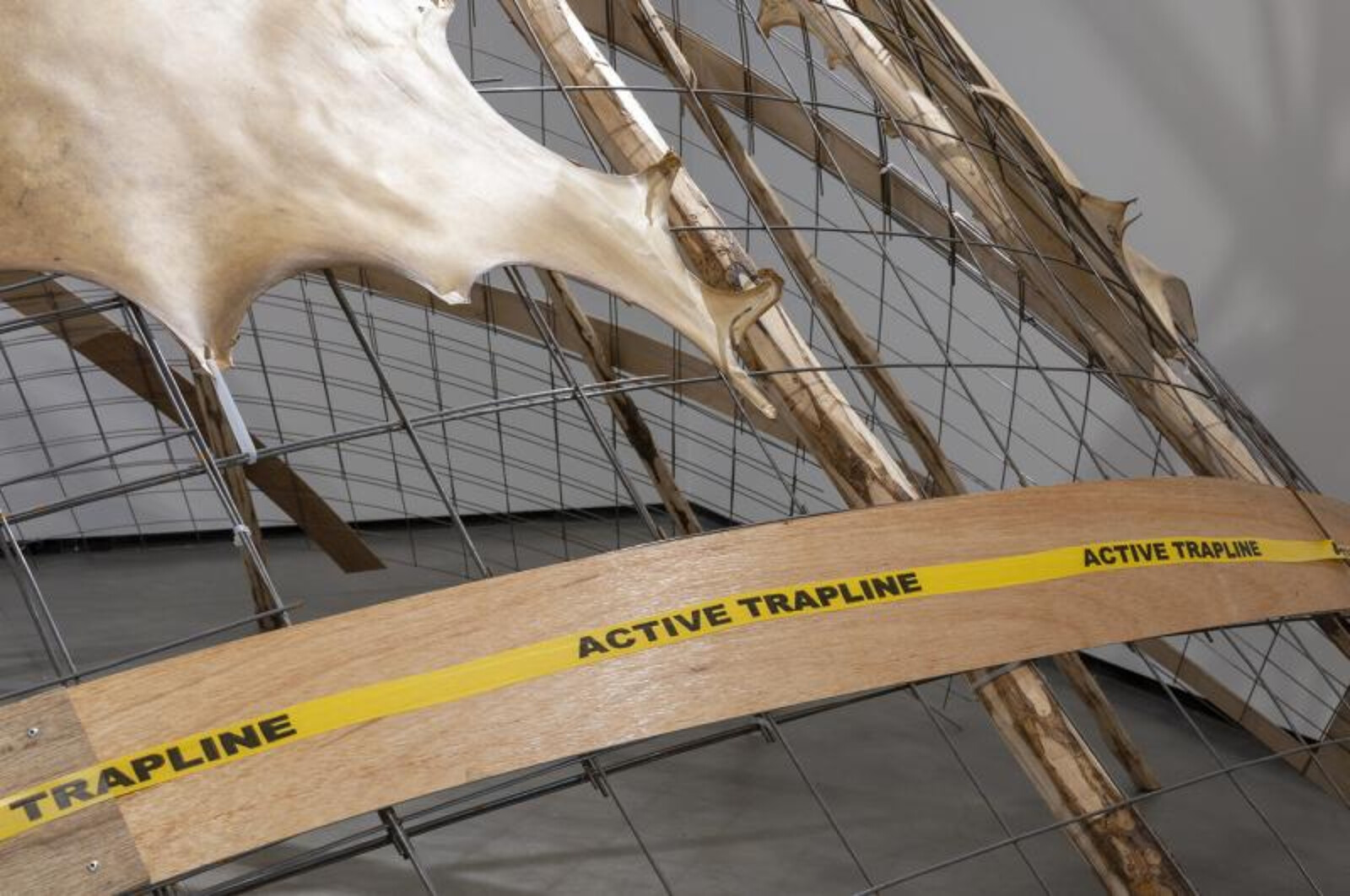

On Models is a collaboration between e-flux Architecture and The Museum of Contemporary Art Toronto.