Global powers often emerge thanks to their intricate relationships with much smaller states, seemingly located at the fringes of such power. Situated at the crossroads of Europe, Africa, and the Middle East, the small island nation of Malta has served throughout its history as a strategic hub for the global economy, movement, and migration, legal and otherwise. Contingent geographies, socialist and independence histories, and tactical associations make Malta a kind of territory- and nation-as-infrastructure for planetary geopolitics. This role has shaped its foreign policy and economic alliances, often sacrificing its landscapes at a cost to its actual citizens and leaving them without recourse to their nation’s Idealpolitik leverage.1 Malta is still a portal to and buffer for contemporary developing global networks, exemplified by contemporary Chinese interests and infrastructures like the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and Huawei’s communications networks.2

This contradictory status, as a beneficiary and battleground of global influence, crested in the 2017 car-bomb assassination of journalist Daphne Caruana Galizia, who worked to expose the markedly corrupting effects of foreign investments in Malta. These and other developments embroil the maritime Maltese in the intentions and extensions of many powerful nations’ interests and pursuits. China’s interactions with Malta now seem specifically designed to enable a kind of infrastructural governance that paves the way to European market access for state-owned Chinese interests, partly through the widespread physical installation of Chinese technologies, workforces, and facilities. As such, Malta continues a decades-long negotiation with Western and Eastern power brokers, outlining very specific European, Mediterranean, and Maltese forms of governance.

After a few years of thwarted plans, stalled infrastructures, and canceled gatherings over the pandemic period, we finally arrived in Malta in the summer of 2022.3 Together with our colleague Merve Bedir, we set out in search of documents and monuments to globalized infrastructure on the islands.4 We sought to catalog the physical impacts left by the geopolitical disorder and bureaucracy that was so amplified by the lockdowns and Covid-19 biopolitics, but that has its roots in antediluvian planetary flows, Cold War deadlock, and age-old techniques of imperial expansion. In short, we hoped to find material witness to the complex geopolitical dynamics playing out in Maltese landscapes, waterways, and airspace. Could we read the documents that enable infrastructural transformations back from material monuments? Would we be able to traverse the seas that separate state-level decision-making from situated infrastructural interventions, centralized policymaking from local territories, technical planning from actual practices, Malta from the European mainland? We sought to reach those places where abstract policy and decisions had physically changed the island, its flows, and its landscapes.

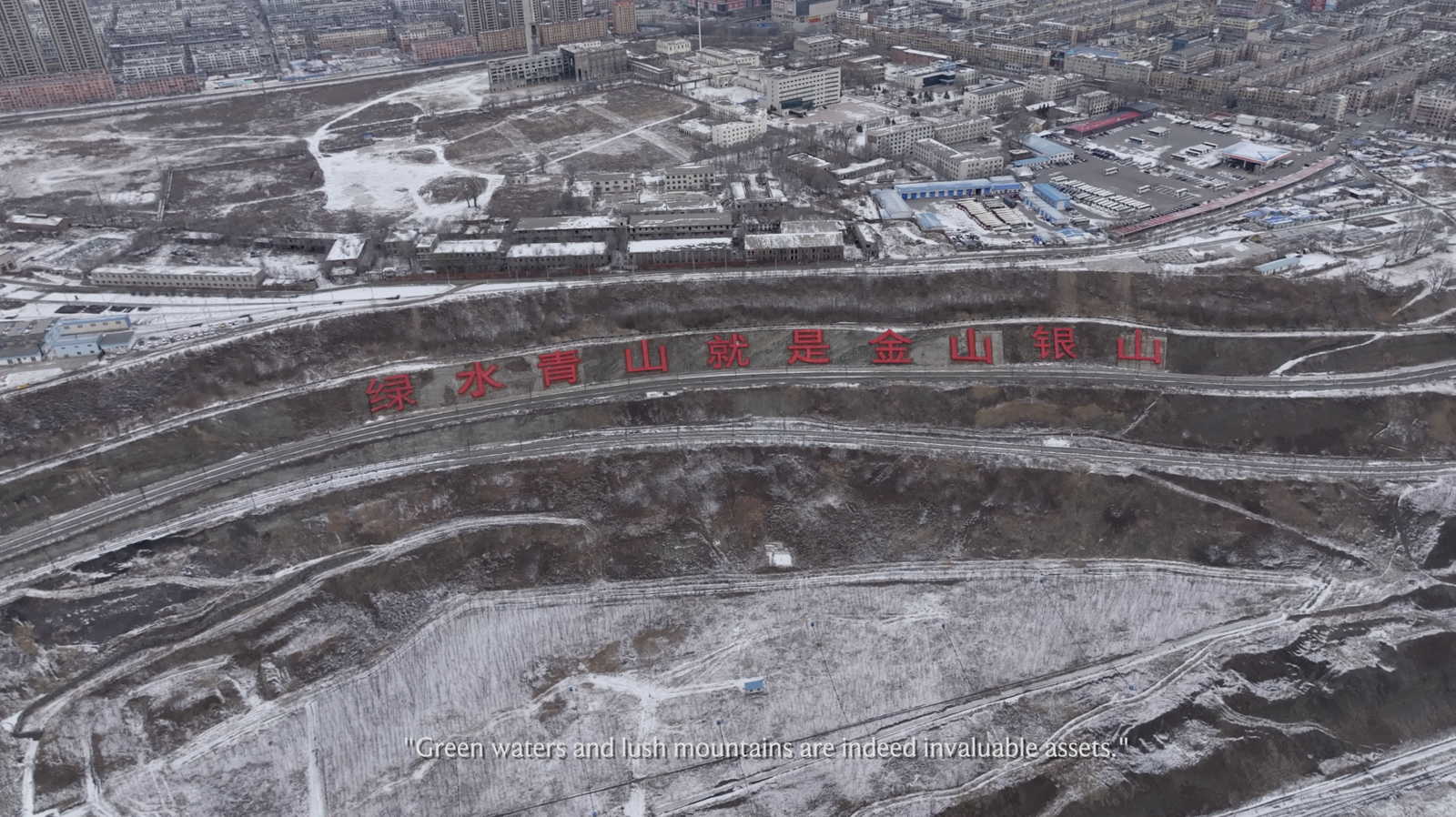

Over what became multiple visits, we stopped in places like the megalithic temple Ġgantija on Gozo Island. Ġgantija contains some of the oldest free-standing structures in the world, helping to underwrite a Mediterranean pride (not unique to Malta) that understands itself as the originator of European “civilization.”5 Aboard a luzzu, a traditional Maltese wooden boat, we were swept by the entrance of the largest dry dock in Europe, the Palumbo Shipyard, and the gigantic container ships that dock in Valetta’s Grand Harbor. The 300,000-ton Palumbo dock, locally referred to as “Red China Dock,” was built with funding, know-how, and labor support from China starting in 1975.6 Just across the bay from the dock, we were given a tour of a seventeenth-century neoclassical villa used by the British in the early nineteenth century as a Royal Naval Hospital. The Maltese islands were referred to for decades as the “nurse of the Mediterranean,” a moniker that harkens back to much earlier associations with the healing brotherhood of the Knights Hospitaller. These sites give physical relief to a strategic culture and culture of strategy that still shape decision-making and foreign policy in Malta, a state that only achieved independence from a long line of colonial rulers in living memory.7

Malta comprises five islands—Malta (the largest), Gozo, Comino, and the uninhabited islets of Kemmunett and Filfla.

Throughout its history, Malta has served as a kind of hub for mediation, where others would stop and negotiate foreign interests. As a result, its people, one could conjecture, became needfully adept at receiving, hosting, and then saying goodbye to foreign influences while attempting to arrange and safeguard local interests. Even what is considered the most important single event in the country’s history refers to the uninvited arrival of foreign interests: St. Paul the Apostle’s shipwreck on Malta is said to be described in the New Testament: “we found that the island was called Melita.”8

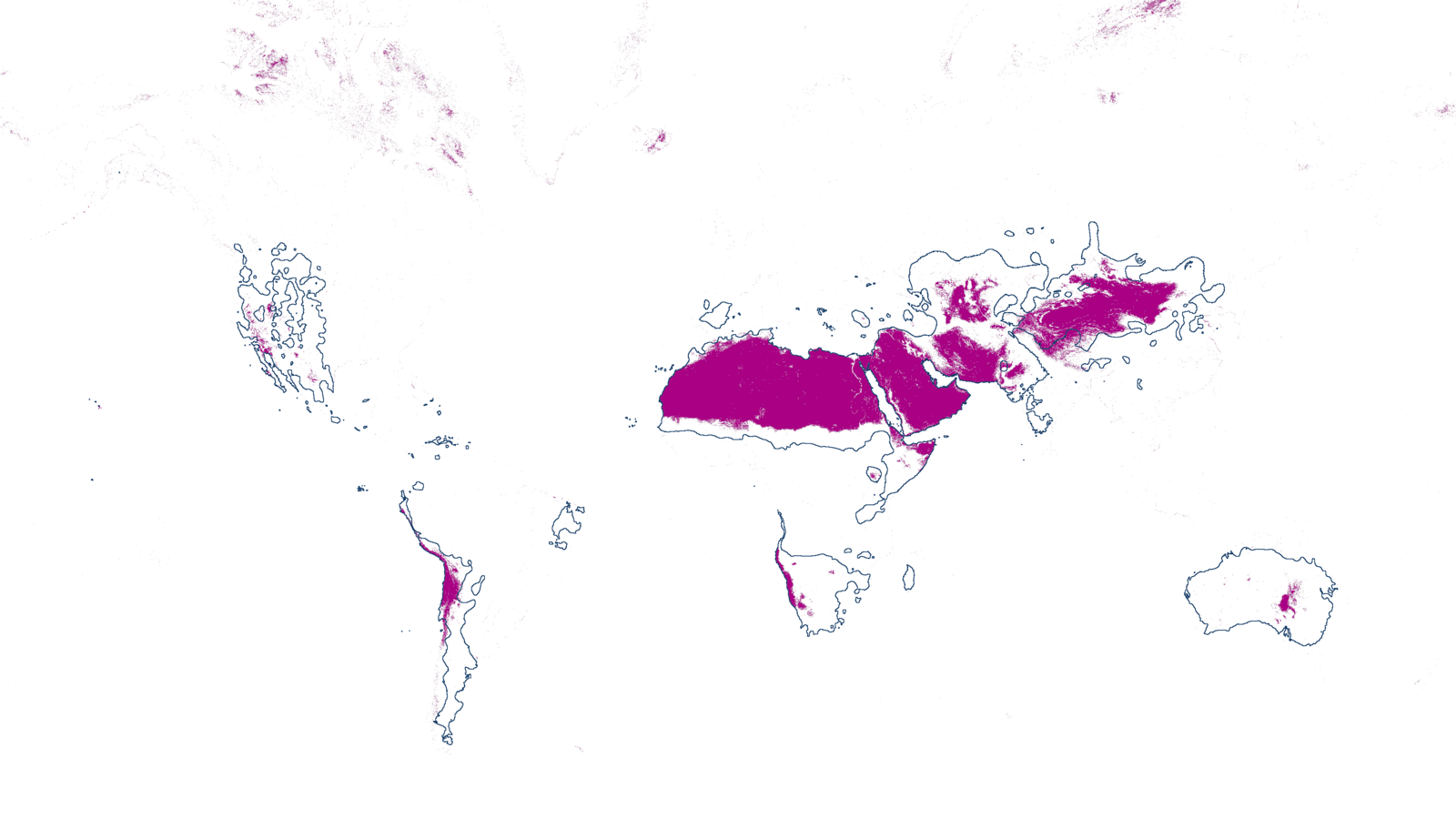

Malta was a frontline defense against invasions of Europe during the Crusades and the Ottoman-Habsburg wars. Under British rule from 1814 to 1964, Malta allowed Britain to protect its interests in the Mediterranean and acted as a deterrent against Axis powers during World War II. During the Cold War, Malta became a member of the Non-Aligned Movement, declaring itself a neutral state in 1980 and mediating between members of Western and Eastern blocs. The movement of Bangladeshi, African, Syrian, and other non-European nationals to and through Malta has for centuries been a contentious, infamous, and deadly issue. Recent migration exponentially increased in the early 2000s, with the escalation of conflict in the Middle East and the closure of Lebanon, Jordan, and Egypt to Syrian asylum seekers. All this became more complex after February 2022, when Russia invaded Ukraine and Malta activated temporary protection for displaced persons.9 The movement of people fleeing conditions elsewhere into Malta (and so the EU) is paralleled and in many ways contradicted by its “golden passport” program (also known as the “Malta Citizenship by Investment Program”). Golden passports put an explicit price on European citizenship—a property investment of around €700,000—making glaringly obvious the less-than-scrupulous class and racial determinants that underly the “freedom” of mobility in democratic Europe. Throughout the long twentieth century, Malta consistently presented itself as a bottleneck and a gateway, regulating flows with outsized, dire, and dramatic moral and mortal consequences.

Prime Minister Joseph Muscat overseeing the signing of a Memorandum of Understanding between the Maltese Parliamentary and Huawei Italy’s CEO, Edward Chan, on April 6, 2016.

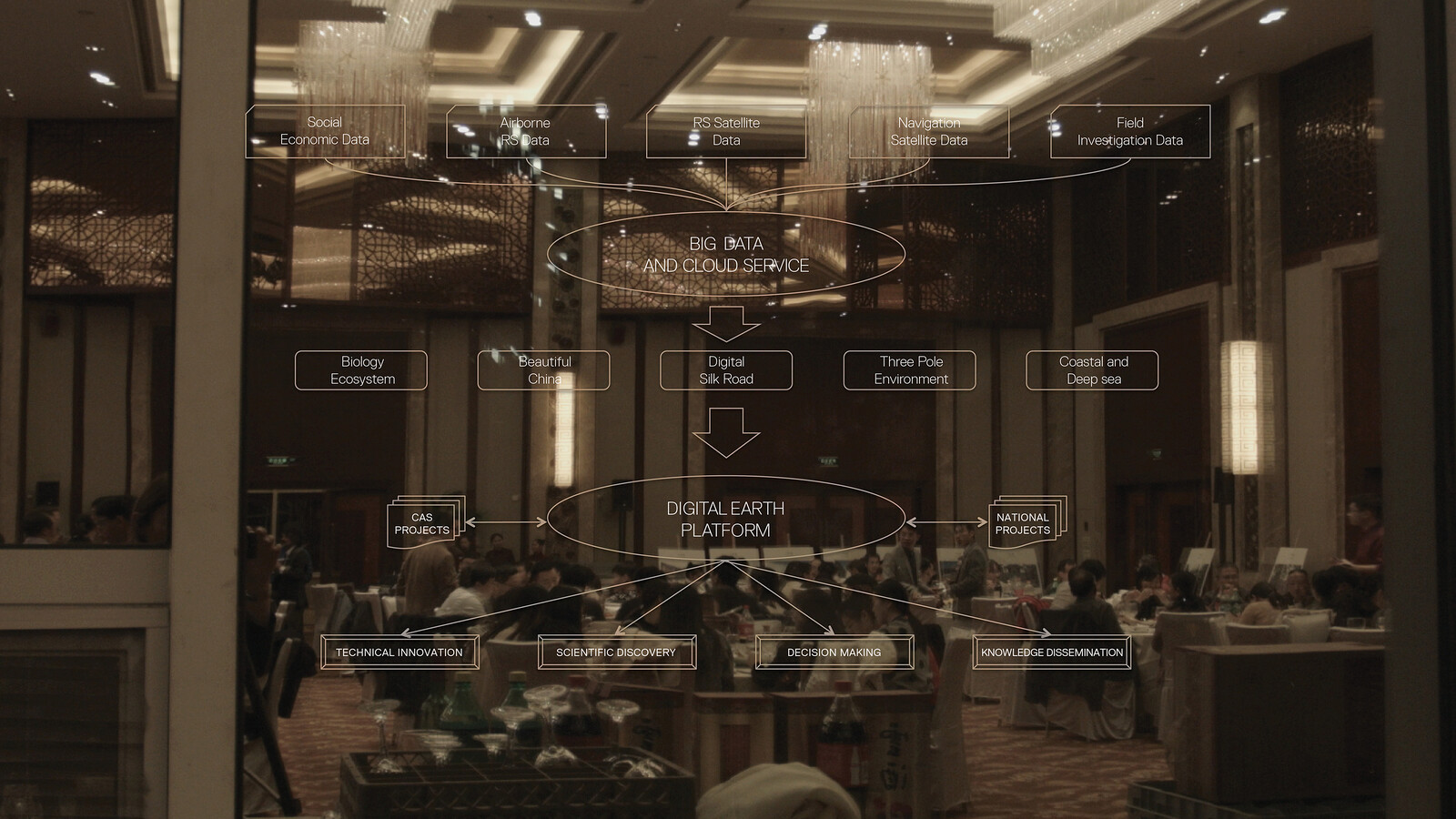

On another visit to the islands, we wandered around the capital city of Valletta through the streets of Paceville, a lively, boisterous party and tourism district full of late-night bars. We looked for, and found, camera and antenna installations that were part of a “Safe City” pilot project that started in 2018. The project, designed and using hardware leased to Valletta by Huawei, is purportedly meant to implement a digital video surveillance network, AI facial recognition and tracing, and a prototype 5G network. Safe City was installed on the back of multiple Memoranda of Understanding signed between Huawei and Malta over the 2010s—a period marred by corruption allegations, conspiracy theories, and, it turns out, actual conspiracies within government operations and reputations. Flying in the face of express concerns, as well as embargos against the Chinese telecoms giant by the US, countries in Oceania, and EU and national offices in Brussels, the Safe City project and the 5G network that enabled it proved controversial on grounds of public health, individual privacy, and data ownership. A year or so after its launch, courts fielded claims that it was illegal, and it was completely dismantled by 2023. Safe City is the kind of project that emerged from the “pressure on countries to accept Huawei for 5G” felt in the late 2010s, as the company shopped around for European and global adopters of their higher speed (and higher radiation) networks.10 Similarly, China-centered digital and BRI-related programs by the company—from retail purchasing systems to supply chain logistics to transport automation solutions—have since proliferated, predominantly in Southern and Eastern Europe, where finance for infrastructure can be harder to come by.11

We also ventured outside the city to visit the Delimara Power Station, a facility that Shanghai Power and Electric bought in 2014 from Enemalta, replacing the Maltese government-run electricity monopoly that had been operating it up until that time. The €320 million purchase was the largest foreign investment ever made in Malta, a deal that continues to be the subject of investigations and corruption allegations. Many of these were initially reported on the website of the Maltese journalist and activist Daphne Anne Caruana Galizia. Her online reporting implicated European politicians, a Chinese state-owned company, and their consultants in kickback and bribery schemes, all of which triggered a political crisis that drove then-Prime Minister Joseph Muscat from office in 2020. Daphne herself was brutally and publicly assassinated in a car bombing on October 16, 2017, an act that has now been tied to China through Chinese infrastructural ventures in Malta and Montenegro.12 When we got back to Valletta from the power station, we visited the re-signified Great Siege Monument statue in downtown Valletta, now a central site for protests, gatherings, and demands for justice, where flowers and tributes are regularly placed in memory of Caruana Galizia.

When you drive southeast in Malta, toward the Malta Freeport in Marsaxlokk Harbor, you can veer through the small town of Birżebbuġa.13 Dawret il-Qalb Imqaddsa is a two-lane road in Birżebbuġa that wraps itself around a small peninsula covered in oil storage cylinders owned by the state-run fuel monopoly, Enemed. Once Enemalta’s fuel division, Enemed was split off as its own entity in 2014 by then-Energy Minister Konrad Mizzi, who also brokered the sale of national electrical infrastructure to Chinese companies. Mizzi and his wife, Chinese-national Sai Mizzi Liang, continue to be maligned by accusations of corruption and of having used political influence for their own benefit.

Across the street from the Dawret il-Qalb Imqaddsa entrance to Enemed’s facilities is a tall modernist sculpture, about four meters tall, with two ribbon-like arms. It is easily overlooked against the landscape of Enemed’s massive petrochemical storage tanks, the huge, elongated pipeline jetty that reaches out into harbor waters, and the battery of gargantuan crane derricks operating at the port across the bay. The sculpture is a memorial, a monument to “The End of the Cold War,” a phrase inscribed on its front surface beneath two abstracted armatures that appear to be hugging one another. The sculpture has wound up unceremoniously positioned next to a parking lot for Birżebbuġa’s otherwise industrial promenade, but what it memorializes is an extraordinary meeting that took place at Marsaxlokk Bay in 1989: the Malta Summit.

The Malta Summit was held aboard the Soviet cruise ship Maxim Gorky while docked during a heavy sea storm in December 1989, just a few weeks after the fall of the Berlin Wall. US President George H. W. Bush and Soviet Premier Mikhail Gorbachev shared a meal in the ship’s wardroom, which is where Gorbachev pronounced, “The world is leaving one epoch and entering another,” and Bush said, “It is within our grasp that each contributes to overcoming the division of Europe and ending the military confrontation.”14 One can imagine how in 1989 the promenade at Birżebbuġa would have been overrun with throngs of onlookers, tripods, and telescopic camera equipment, as reporters captured a well-orchestrated meeting between the leaders of the world’s two superpowers. The Malta Summit was in fact staged predominantly for the cameras, as little else took place at the meeting beyond handshakes, posturing, and pronouncements: no treaties were signed, no deals were made. Its staging nonetheless succeeded in creating a spectral signal that made its way around the world and effectively ended the Cold War as the pivotal not-so-stalemate of twentieth-century world history. The Malta Summit was as substanceless and meaningless as most Memoranda of Understanding; it was a media incantation that also famously indicated, for some, the end of history, or at least a particular kind of it.15

We can now see that the planetary signal sent from the cold waters of Marsaxlokk Bay in December 1989 was not an end, but something more like a meta-end to something of a meta-war that continues into the present. Our current moment is afflicted with asymmetric violations and violence that reinscribe Cold War-era scars, wounds, and lines of incision, including the war in Ukraine and Israel’s systemic destruction and genocide in Gaza, to name but two. These conflicts, aggressively but quietly involving direct and indirect support from the US and European powers on one side, and Russia and China on the other, show the deep entrenchment of transhistoric axis/ally dualisms. Through the provision of weaponry, official statements, and political theater, world powers exhume Cold War specters over and over again.

The largely residential Santa Luċija neighborhood in Malta is not among the island’s main tourist areas. Located roughly between downtown Valletta and the nation’s main international airport, a few visitors may stop to see the Hal Saflieni Hypogeum, but fewer stop to visit the Chinese Garden of Serenity on the other side of the highway. We visited this exceptionally odd public park on an exceptionally hot and muggy late afternoon. Wandering through meticulously designed yet somewhat unkempt pavilions, bridges, and ponds, we were left with the kind of incredulous feelings that accompany somewhat random, incongruous acts of architecture and urban planning. The construction of this particular cultural translocation started in September 1996, as a gift to Malta from the People’s Republic of China. The garden was opened and officially inaugurated by then-Prime Minister Alfred Sant on July 7, 1997, well before Malta joined the European Union in 2007. The garden has received multiple infusions of funding, refurbishment support, and new features from China, Chinese companies, and Chinese artists since the late 1990s.

The Chinese Garden of Serenity is a monument to a geopolitical odd couple: the tenth smallest country in the world, Malta, and what was until 2023 the most populous country in the world, China. The project’s prehistory comprises a slew of memoranda signed by Malta, China, and Chinese companies starting as early as the 1970s, describing general collaborations on everything from technology transfer, educational cooperation, development, and military aid, to cultural, sport, and “sister city” exchanges between the two countries. In November 2018, Malta and China signed another memorandum of understanding for “cooperation within the framework of the Silk Road Economic Belt and the twenty-first century Maritime Silk Road Initiative,” which provided “the basis for projects, investment, and cooperation in the trade, financial services, and tourism sectors to be carried out between the two countries.”16 In 2019, Italy was politically lambasted for being among the first European countries to sign on to the Chinese initiative, but reports quickly shifted to pointing out that Malta had already signed up a year earlier.17 Today, up to thirty-four European nations and 150 countries worldwide have signed similar agreements with China.18

The Chinese Garden of Serenity includes a brass statue of the Maltese political figure Dominic Mintoff, a socialist politician and architect who was a dominant figure in Maltese politics for decades in the postwar period. In memos by the US Central Intelligence Agency and others, he is said to have inaugurated a Maltese style of playing the East off the West, and vice versa, for both national and personal benefit.19 Mintoff personally visited China in April 1972, securing diplomatic relations and Chairman Mao’s promise to help Malta loosen the economic grip of the West on the impoverished island nation. When Mintoff returned to Beijing in 1984, a North Korean troupe sang a Chinese hymn of protection and preservation in Maltese for Mintoff.20

However odd, Malta-China linkages can be both plausible and real, as well as spurious and wholly fabricated. During the Covid-19 pandemic, China provided Malta with supplies and assistance, and shared knowledge and information on how to combat the virus. In 2020, Chinese donors gave 20,000 unsolicited face masks to Malta, distributed primarily in Valletta by the Malta Trust Foundation. Other Chinese companies and interests active on the island through the Malta-China Friendship Society shipped in tens if not hundreds of thousands more, as well as vaccines, food, water, and other supplies. This material aid dwarfed what Malta received from Brussels during this period, a fact lost on neither Maltese politicians nor the populace. In their time of crisis, the biological health of islanders was protected by Eastern, more than Western, powers.

In May 2020, an exhibition entitled “Our Silk Road” went up in Valletta at both the China Cultural Center (“a non-profit cultural organization dedicated to promoting understanding and appreciation of Chinese culture”) and at the old open-air theater, Pjazza Teatru Rjal.21 The photography exhibition was held at a time when the Chinese presence, business dealings, and (golden) passport purchases in Malta were extremely contentious, yet the show featured exclusively harmonious images of contemporary life along the vaguely drawn routes of the projected BRI. Coinciding with the second Belt and Road Forum for International Cooperation in Beijing, the intent of “Our Silk Road,” according to the Chinese ambassador to Malta at the exhibition’s opening, was to illustrate “mutual understanding and mutual benefits under the Belt and Road Initiative” and to promote “the Belt and Road Initiative and build a community with a shared future for mankind.”22

While ties between the two nations’ histories can be contrived, they can also be wholly fabricated. An online slide presentation by one “Richard G. Evans” called “Cultural Links between China and Malta” names archaeology, architecture, and astronomy as elements that “form a fascinating cultural link between the two countries,” but strains to argue what this link constitutes in later slides.23 On our visits, we heard locals associated with the China Cultural Center in Malta tell stories of undocumented ancient exchanges between the Phoenicians, who had a significant presence in Malta, and Chinese traders navigating the maritime paths of the Silk Road long before the Silk Road was even established. Stories like these ask us to imagine how, in the farthest reaches of antiquity, Chinese silk and spices made their way to Malta, where they were traded for the island’s prized honey and textiles. Through such narratives, the Belt and Road Initiative is revised and re-cast not as a novel linkage of Maltese and Chinese interests and infrastructures, but as a historical imperative to reconnect a partnership and friendship long-thwarted by centrist European powers, Western capitalism, and Eurocentric cultural elitism.

The small island nation of Malta, known primarily as a Mediterranean tourist destination, is a strategic foothold for China’s expanding presence in Europe, as Malta’s influence, products, and energy infrastructures move north and west. At the crossroads of Europe, Africa, and the Middle East, Malta has always been a coveted prize of empire, from the Phoenicians to the Romans, Arabs, the British, and now, it would seem, the Chinese. As a testament to Malta’s strategic acumen and historical sensitivity to asymmetries of power, Malta leverages this historical continuity to play the EU off China, Brussels against Beijing, and vice versa. By positioning itself as an indispensable node in China’s global network of trade and influence, Malta strengthens its own economic position. The symbolic, tangible, and imaginary connections between Malta and China—from material infrastructure like Red China Dock and the uncanny Chinese Garden of Serenity to imagined histories and much-needed pandemic aid—all gesture towards the transformed relations yet to come, relations that are haunted by ghosts of empire, the face of new yet familiar and expanding imperial influence.

Idealpolitik emphasizes the role of historical and cultural practices, ideals, and principles in policy-making and foreign affairs. It is juxtaposed to realpolitik, which instead values transnational activities and decision making based on the achievement of concrete ends. See, for example: John Bew, “The real origins of realpolitik,” The National Interest 130, February 25, 2014, 40-52.

Angelico Baldacchino, “Are there any potential security challenges in relation to Chinese foreign direct investment in Malta?” (Master’s thesis, University of Malta and George Mason University, 2020).

Part of a group research excursion and summer school entitled “Media, Migration & Governance: Advanced Practices” that took place online in 2020 and 2021, and then in Malta in 2022. Events were co-organised by the Global Emergent Media Lab, Critical Media Lab Basel, and the University of Malta, in partnership with African Media Association Malta, The National Community Art Museum MUŻA, and Spazju Kreattiv as part of the European Forum for Advanced Practices COST Action. Gratitude to Michaela Büsse, Adnan Hadziselimovic, Catherine Willems, Clemens Apprich, Joshua Neves, Margerita Pulè, Hagen Kopp, Marcell Mars (aka Nenad Romic), and Tomislav Medak for their advice, involvement, and support throughout the complex and transformative 2020-2022 period. Huge thanks as well to Maltese scholar and policymaker Angelico Baldacchino for our discussions and for reading early versions of this text.

Art historian Erwin Panofsky suggests that documents (as the total accumulation of artefacts or traces of human-made events and ideas that survive into the present) and monuments (artefacts, events, or ideas that impress upon us a contemporary urgency for recognition, interpretation and meaning, also by) should form the basis of a more object-centered critical cultural studies and humanities. Later, Michel Foucault transformed how history itself is (and should be) written in shifting attention to either of these two broad evidential categories. His call was for a deeper sensitivity to, and acknowledgement of, the now seemingly commonplace yet nontrivial idea that there are no transparent mediums for recording and transmitting the recent or distant past.

See for example: Heritage Malta and Mark Miceli-Farrugia, “Europe’s oldest civilization: Malta’s temple-builders” (United States Embassy of Malta, 2001). Or, as then President of the Parliament of Malta, Michael Frendo reminded everyone in his speech to the Shanghai Institutes for International Studies in China in 2012: “There is no Europe without the Mediterranean and no Mediterranean without Europe.” Michael Frendo, “Developing a vibrant partnership between China, Europe and the Mediterranean: The role of Malta and its Parliament,” Address to the Shanghai Institutes for International Studies, Shanghai, China, September 2012, ➝.

Two construction workers, Gu Yanzhao and Xu Huizhong, who died during the construction of the dock, are celebrated by the Shanghai Daily as having “sacrificed their lives during the construction of the No. 6 Dry Dock in Malta’s capital city” in 1979. Xu was hit by a falling piece of equipment, while Gu died of liver cancer, offsite. They are buried in the otherwise mostly Catholic Addolorata Cemetery, a short walk from the Chinese Garden of Serenity in Santa Lucija. See: Li Qian, “Remembering the Chinese engineers who died forging Sino-Malta friendship,” Shine, January 10, 2022, ➝.

Hillary Briffa, “Neutrality and Shelter Seeking: The Case of Malta,” in Small States and the New Security Environment, eds. Ann-Marie Brady and Baldur Thorhallsson (Springer Cham, 2021).

“Melita” is the ancient (and, some believe, biblical) name of Malta, perhaps referring to the honeys that were produced on the islands. Melita is the original name of the ancient capital of Malta (now Mdina), and still the name of Malta’s neoclassical national personification as a female figure (common in the nineteenth Century). Melita is to Malta as Britannia is to the UK, or as Helvetia is to Switzerland.

Migration from Ukraine to Malta is regulated by a document issued by the European Union Agency for Asylum. See: Malta, European Union Agency on Asylum (June 2022), ➝.

Ann-Marie Brady and Baldur Thorhallsson, “Small States and the Turning Point in Global Politics,” Brady and Thorhallsson, eds., Small States and the New Security Environment.

Huawei also finances and helps run the “One Thousand Dreams” program in Albania, which aims to train 1,000 information technology (IT) professionals for the company, donate 1,000 books to university libraries, and provide 1,000 toys to children’s hospitals. Additionally, 29 Albanian government officials and scholars have participated in short-term visits to China to learn about the country’s agricultural techniques, among other aspects to the program. See: “Huawei Launches the One Thousand Dreams Program to Improve ICT Education for the Youth and Provide Care for Children in Central and Eastern Europe,” Huawei, April 12, 2019, ➝.

Stephen Grey, Engen Tham, Jacob Borg and Christoph Giesen, “Special Report: Money trail from Daphne murder probe stretches to China,” Reuters, March 29, 2021, ➝.

Many Chinese state-owned companies have acquired significant stakes in the Malta Freeport Terminal, a major transhipment hub that connects Europe to global maritime trade routes. See Dario Cristiani, Mareike Ohlberg, Jonas Parello-Plesner, and Andrew Small, Security Implications of Chinese Infrastructure Investment in Europe, German Marshall Fund of the United States (September 2021), ➝.

Richard Sakwa, “Back to the wall: Myths and mistakes that once again divide Europe,” Russian Politics 1, no. 1 (March 2016): 1-26.

Francis Fukuyama, “The End of History?,” in The New Social Theory Reader (pp. 298-304), 2nd edition (Routledge, 2008).

Times of Malta, “China, Malta sign MOU within Belt and Road Initiative,” Belt and Road Portal News, November 8, 2018, ➝.

“Italy slammed for thinking about China’s Belt and Road Initiative, but Malta has already signed on,” The Malta Independent, March 14, 2019, ➝.

Christoph Nedopil, “Countries of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI),” Green Finance & Development Center, FISF Fudan University, 2023, ➝.

U.S. Central Intelligence Agency, “Malta: Closer Ties with the East?,” Directorate of Intelligence, 1984, ➝.

Daphne Caruana Galizia, “If this had not really happened, we wouldn’t have been able to make it up. Available here,” blog, November 11, 2013, ➝.

China Cultural Centre in Malta, ➝.

“’Our Silk Road’ photo exhibition opens in Valletta,” Xinhua, April 27, 2019, ➝.

Richard G. Evans, “Cultural Links between China and Malta.” SlideShare presentation, November 6, 2015, ➝.

New Silk Roads is a project by e-flux Architecture in collaboration with the Critical Media Lab at the Basel Academy of Art and Design FHNW and Noema Magazine (2024), and Aformal Academy with the support of Design Trust and Digital Earth (2020).