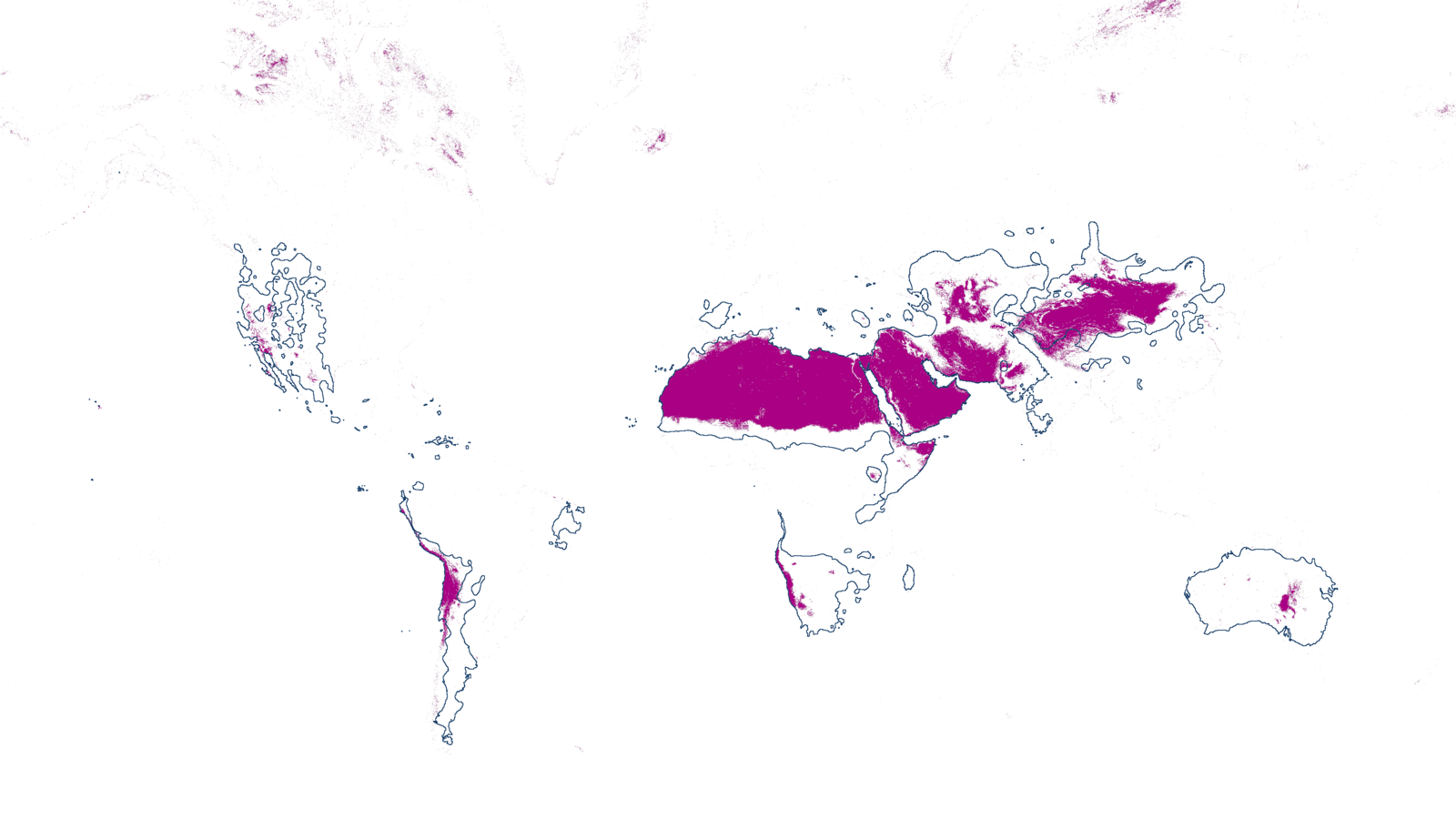

On September 8, 2013, Chinese President Xi Jinping gave a speech at Kazakhstan’s Nazarbayev University to launch the Silk Road Economic Belt (SREB), the overland component of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).1 President Xi opened the speech by evoking images of a deep history of interchange between China and Central Asia, positioning the initiative as the logical reestablishment of those historical connections by way of development, facilitating economic flows across Eurasia via overland infrastructure and transportation networks. In parallel to these spatial connections—pipelines, road systems, hydroelectric plants, and rail lines—Xi’s speech promised the development of human and sociocultural connections—a reunification of the peoples who had shared in this ancient storied past through contemporary economic, energy, and security policy goals.

As observed by political scientist Bhavna Dave, the speech’s site—Nazarbayev University in Kazakhstan’s capital of Nur-Sultan (then Astana)—reinforced Kazakhstan as a critical symbolic site in the project as a whole.2 Kazakhstan, which shares a nearly 1,800-kilometer-long land border with China, represents a key site in the SREB’s transit corridor. While bilateral cooperation between the two nations predates the BRI project—China has invested in energy sector projects in Kazakhstan since the late 1990s—the rate and scale of joint projects has increased dramatically since its launch.3

Two years later, in 2015, President Xi and then-President of Kazakhstan Nursultan Nazarbayev announced that SREB would be linked with Kazakhstan’s Nurly Zhol (or “Bright Path”) infrastructural development program, promising to instrumentalize Chinese financing and expertise to bolster Kazakhstani development. The unified programs focus primarily on three mutually beneficial sectors: transportation and logistics, trade, and manufacturing. These three development priorities are consolidated through one of the most visible BRI-affiliated sites in Kazakhstan: the free trade zone and transit hub located in the border city of Khorgos.

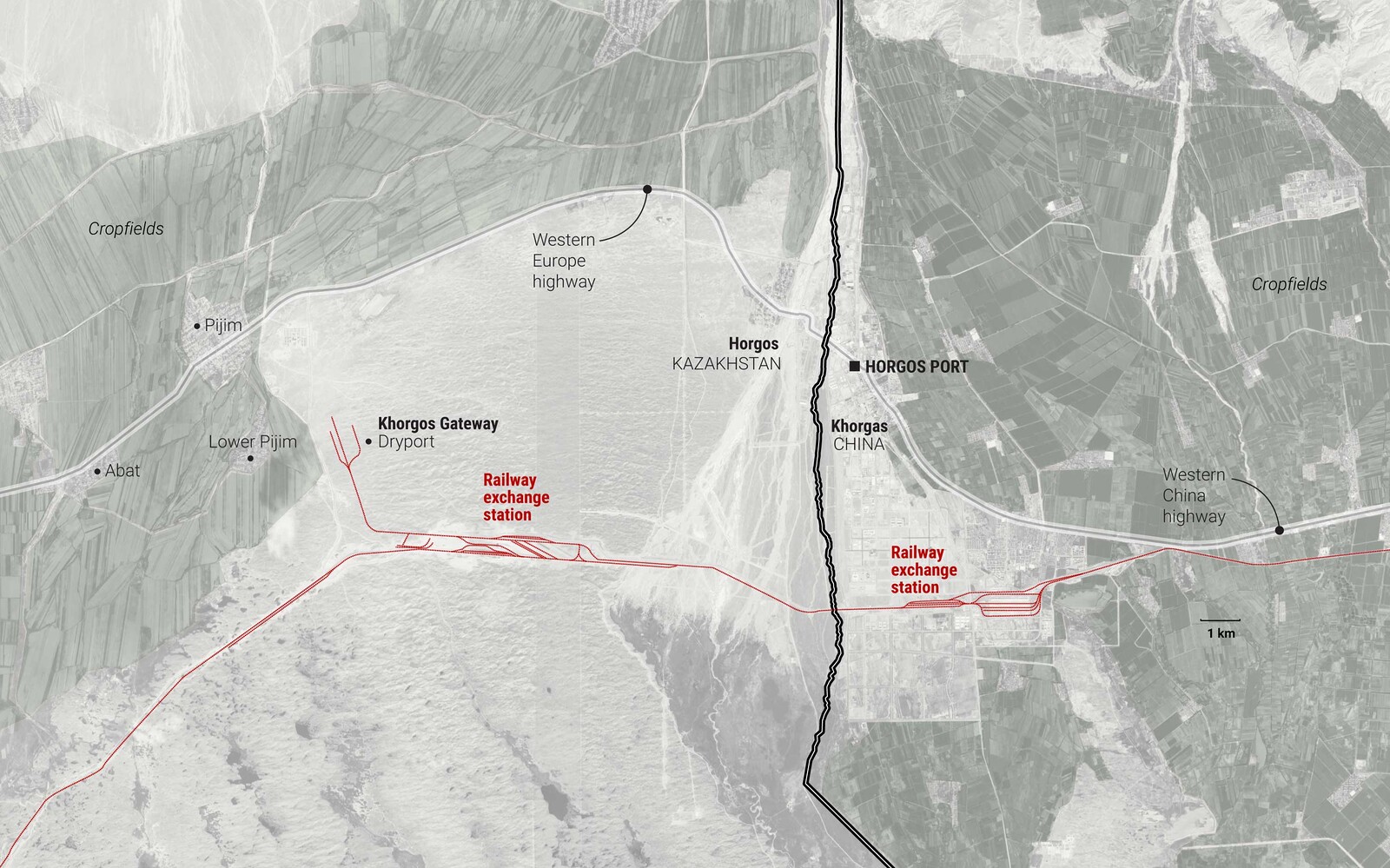

Located in the Panfilov district of Kazakhstan’s southern Almaty region, Khorgos sits across the border from China’s Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region. Technically two cities sitting on opposite sides of the Sino-Kazakhstani border—Khorgos in Kazakhstan, and Horgos in China—the region contains several bilateral projects, including the International Center for Border Cooperation (ICBC), Khorgos-Eastern Gate SEZ, a hydroelectric plant, and new railway and road systems. The cities on both sides of the border have undertaken simultaneous development projects to support transit flows and further elite desires to transform the region into a “new Dubai.”4

Khorgos-Eastern Gate

A special economic zone (SEZ) located just inside the Khazakstani side of the border, Khorgos-Eastern Gate contains Central Asia’s largest dry port, a logistics hub, customs inspection facilities, and an industrial zone. Set near the Eurasian pole of inaccessibility, it is crucial for the movement of goods from China to the West. Yet despite this, within the dry port, references to Chinese involvement are largely absent. The Kazakhstani government has stressed that the loans financing Khorgos-Eastern Gate are from national sources—like Kazakhstan Temir Zholy (KTZ), the national railway company, and the sovereign wealth fund Samruk-Kazyna. However, in 2017, an agreement was signed granting China’s COSCO Shipping and the Lianyungang Port Holdings Group a 49% stake in the project.

A series of marketing videos and a 360-degree virtual tour made in 2016 take potential investors through the spaces of the dry port, allowing them to pan through warehouses, down railway lines, and around the interiors of office buildings.5 Inside the administrative buildings, viewers can click through a series of wood-paneled conference rooms with signage and displays in English, Kazakh, and Russian. In the entryway of the management building, a large map hangs behind the reception desk, displaying the transit routes for cargo passing through the dry port. A strip along the map’s base displays the logo of the zone’s operators and partners: KTZ, the Dubai-based port operations company DP World, and Samruk-Kazyna. Mounted above the map are a series of clocks displaying international times relevant to the port’s operation. The largest central clock is Astana. To either side are smaller clocks set to Berlin and Moscow.

Khorgos-Eastern Gate is frequently portrayed in monumental terms—represented by aerial or worm’s eye perspectives of the massive yellow gantry cranes used to transfer shipping containers. The volume of trade projected to pass through the Khorgos-Eastern Gate is equally monumental.6 In conjunction with digital cargo management software, the expanded facilities of the dry port have more than halved the time previously needed for cargo transfers on the China-Kazakhstan border, making rail freight across Eurasia an increasingly competitive mode of transportation.7 Press releases published by Khorgos-Eastern Gate’s management claim that, by 2020, the facility will have the capacity to process up to 540,000 TEUs per year.8 Yet to date, the dry port has only handled a fraction of that projected trade volume. Speaking to the Astana Times in 2016, Khorgos-Eastern Gate’s CEO estimated that the dry port processed an average of only three to six trains per day.9

Cheaper than air freight and more efficient than shipping goods by sea, frictionless rail connections through Khorgos and across Eurasia are impeded by a relatively minor discrepancy in railway track gauges. While the dimensions of shipping containers are standardized, beginning in the mid-nineteenth century, Russian and later Soviet railways were constructed with a 1.524 millimeter track gauge—0.089 millimeters wider than the gauge standard used in both European and Chinese railways. Due to this incompatibility, cargo must be transferred at the border from wagons operating on Chinese railway lines to those utilized on Central Asian and Russian railway lines. Cargo trains transiting through Khorgos now pass through the dry port, stopping on the six parallel tracks passing beneath its three forty-one ton gantry cranes. Three tracks are built to the 1.435-millimeter width of Chinese railways, and three to the wider width standard to post-Soviet space. There, shipping containers are unloaded from Chinese trains and either stored and processed or transferred to Kazakhstani train carriages. Prior to the trains’ arrival at the Duisburg dry port in Germany, the western extent of the BRI overland transportation network, a parallel operation must occur, with the containers transferred again to railway wagons accommodating the 1.435 millimeter tracks.10

ICBC and the Khorgos Eastern Gate. Image: author, 2019.

ICBC

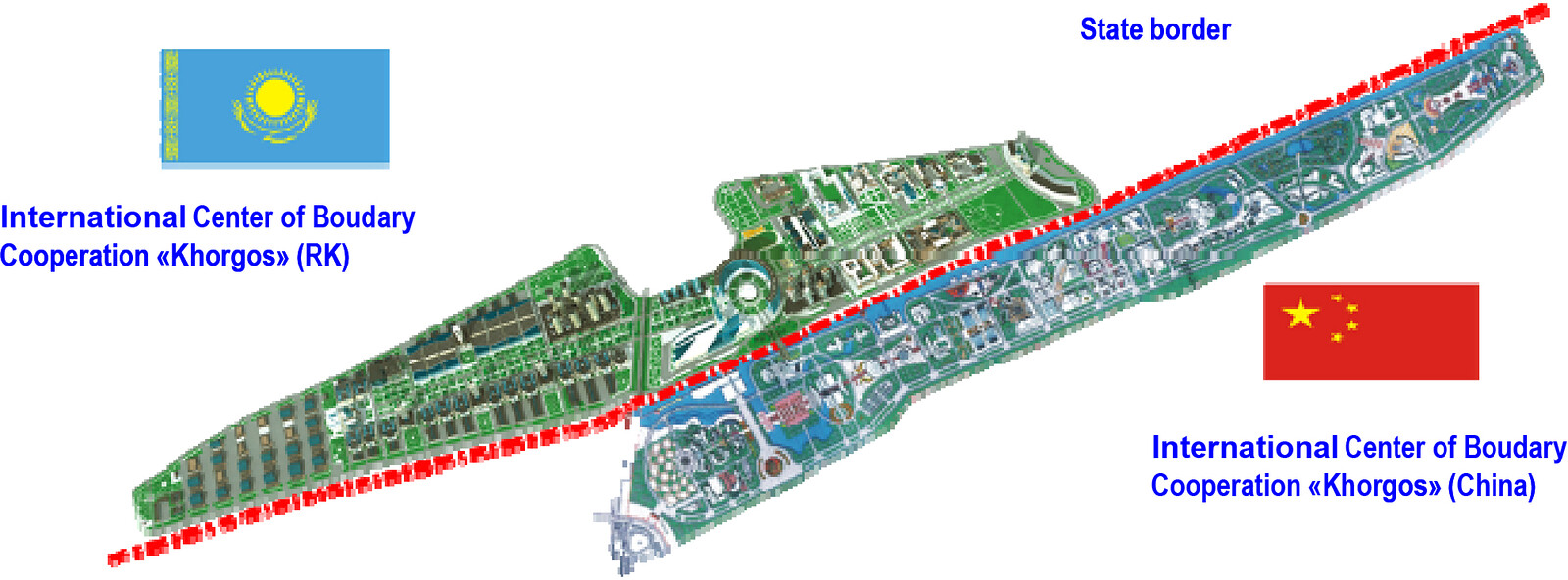

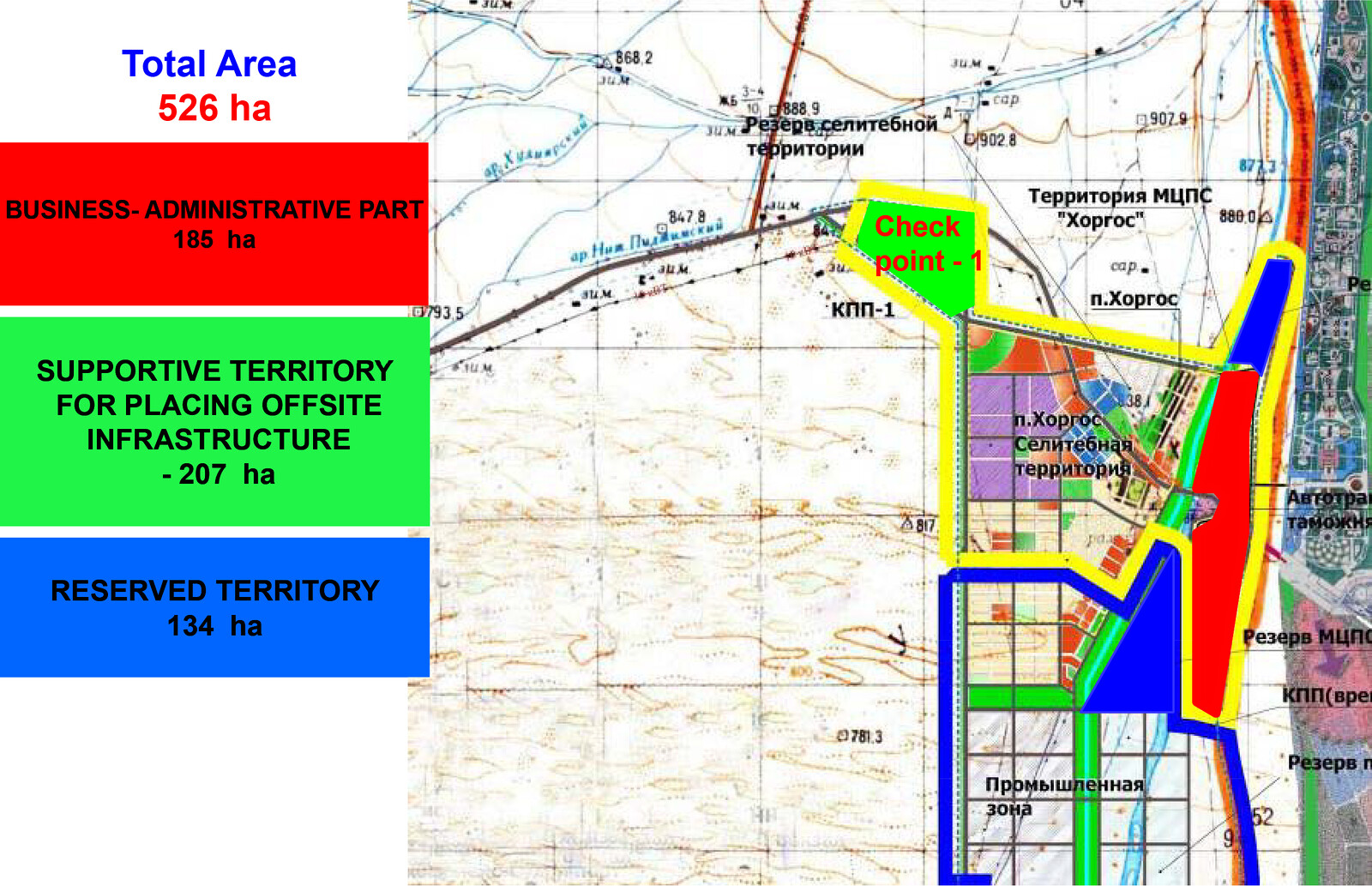

Sitting approximately twelve kilometers to the east of the dry port is the second SEZ, the International Center of Cross-Border Cooperation (ICBC): a 528-square-kilometer special economic zone stretching over both sides of the border. Envisioned as a site of free trade between China and the countries of the Commonwealth of Independent States, a visa-free zone for international business conferences, and an internationally attractive recreation and entertainment destination, agreements concerning the ICBC were first formalized in the mid-2000s.

A linear zone consisting of two offset parallel bars, the two sides of the ICBC have been independently developed by their respective governments. The smaller Kazakhstani section is intended to facilitate the economic development of the greater Almaty region and Kazakhstan at large: providing increased tourism and trade facilities, improving customs processing, increasing the attractiveness of Kazakhstan as a site of foreign investment, and integrating the country into global transportation and economic networks.11

ICBC Khorgos consists of two parts: Kazakhstan and China. Image: AECOM.

The general territory of ICBC Khorgos and its components. Image: AECOM.

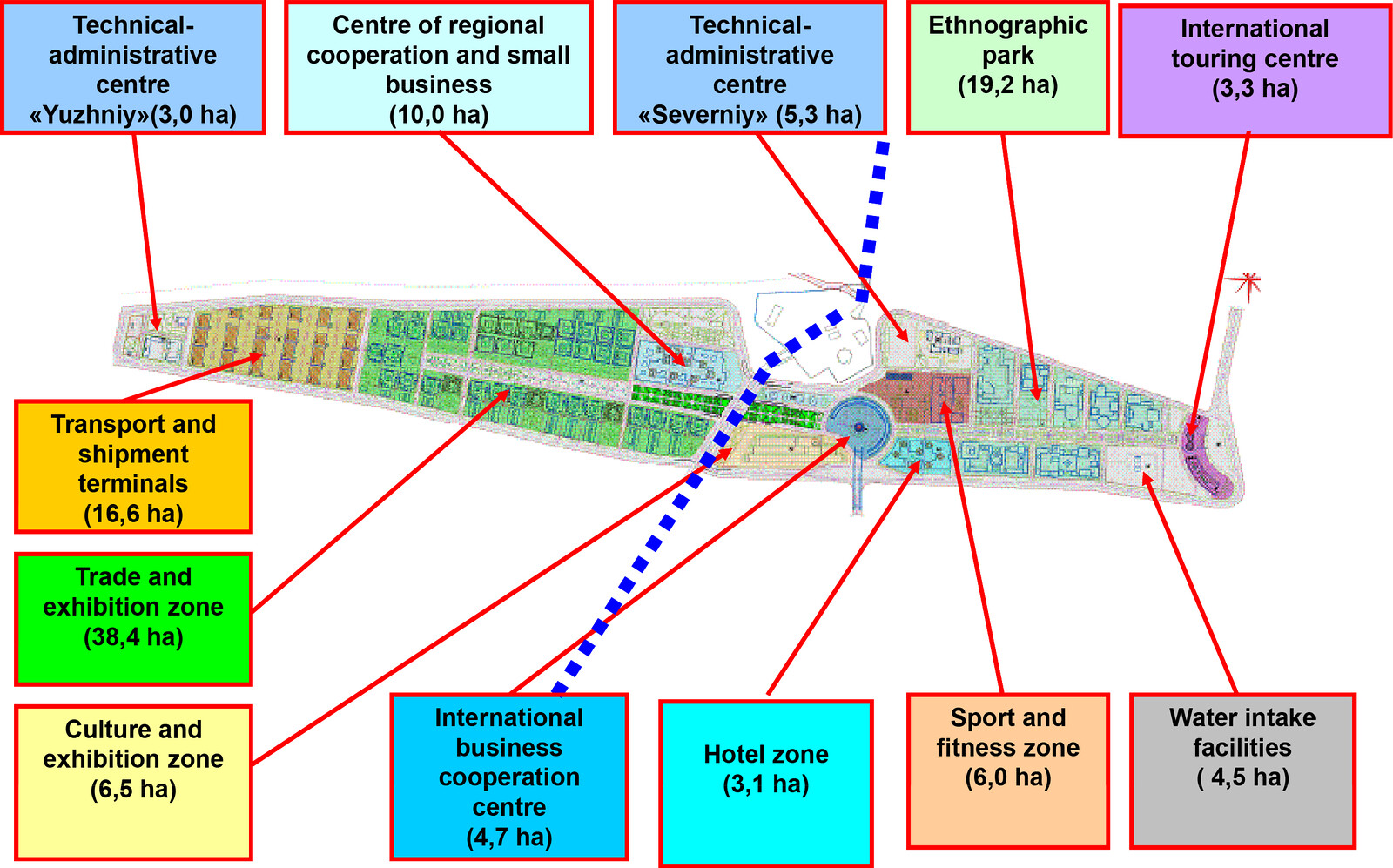

Specific land use of the business and administrative part of ICBC Khorgos. Image: AECOM.

ICBC Khorgos consists of two parts: Kazakhstan and China. Image: AECOM.

Colorful master plans of Khorgos produced by AECOM describe a linear “city” organized around a central green axis. In addition to trade and logistics facilities, the plan, commissioned in 2012 by Kazakhstan’s Ministry of Industry and Trade, allocated plots for an international university, hotels, sanatoria, sports complexes, and an ethno-park featuring blocks of national pavilions displaying crafts and hosting cultural festivals. Presented by the project brief as a city, the initial master plan made no provision for housing, commercial space, or other infrastructures necessary for urban life.12 To date, few of the objects described by the plan have actually been constructed. The city’s growth has largely lagged behind that of its Chinese counterpart. Boasting a population of 85,000 by 2014, in Horgos, the construction of residential districts and high rise towers has already begun.13

At present, railway workers, border guards, customs officials, and others working for Khorgos-Eastern Gate and the ICBC are largely housed in Nurkent, another new city adjacent to the two SEZs. Today a village of 3,000, Nurkent is projected to house 100,000 residents by 2035. While modest by world city standards, this population figure would place Nurkent among the top twenty-five most populous cities in Kazakhstan.14 Government projections assert an aggressive construction schedule, with housing for 50,000 residents slated for completion in 2022. Described in press releases as a super modern cultural hub, featuring “high-rise buildings, an ice arena, museums, and shopping centers,” in its current incarnation, Nurkent is a small collection of single-family homes and low-rise large-panel apartment blocks that recall Soviet-era khrushchyovka housing. These buildings, as well as Nurkent’s school, clinic and a small number of other public buildings, sit on wide, straight streets lined with manicured lawns and surrounded by agricultural land. Essentially a company town—the homes and furniture of its residents have been provided by KTZ—Nurkent is currently administered through the nearby Altynkol station and has yet to appear on maps.

The gateway between Khorgos and Horgos. Photo: author.

Other Crossings

On the border between Khorgos and Horgos, two parallel stone-clad towers occupy either side of a narrow roadway. Displaying the national symbols of Kazakhstan on one side and those of the People’s Republic of China on the other, the towers mark the transition across the two nations. While the border itself was formalized in the nineteenth century, the markers have undergone a progressive series of aesthetic modifications. Today, the towers have been declared a “National Scenic Area,” and their “modern” and open appearance touted as “award-winning.”

The monumental flows of cargo imagined by the BRI, the impetus for this cross-border development, mirror a long-standing plethora of relatively minute transactions occurring daily across the border. In the early 1990s, the collapse of the Soviet Union was paralleled by a similar collapse in the flow of consumer goods from Moscow to Kazakhstan. Largely dependent on these and other imported products, Kazakhstani citizens began crossing the Chinese border to fill the resulting gap and purchase goods for local resale. Facilitated by bilateral agreements between the two nations, in the early 1990s, this practice—known as shuttle trading, or chelnochnikov—provided employment for hundreds of thousands of Kazakhstanis who operated small-scale import businesses.15 The practice remains active to this day. In Khorgos, traders stand in long queues at the customs station waiting to visit malls placed on the Chinese side of the border. Tightly packed with row upon row of stores, their brightly colored signs in Russian and Chinese advertise fur coats, discount clothing, consumer electronics, housewares, and more.

In 2017, restrictions were put in place to limit the quantity and type of goods with which individuals are permitted to re-enter Kazakhstan. To circumvent these limits, an underground economy of unofficial porters has developed, transporting goods across the border for a fee. Traders wait to board buses that will transport them and their cargo back to Kazakhstan, and when no more passengers can crowd inside, those remaining on the street pass plastic-wrapped bundles of goods through the bus windows to their partners inside.16

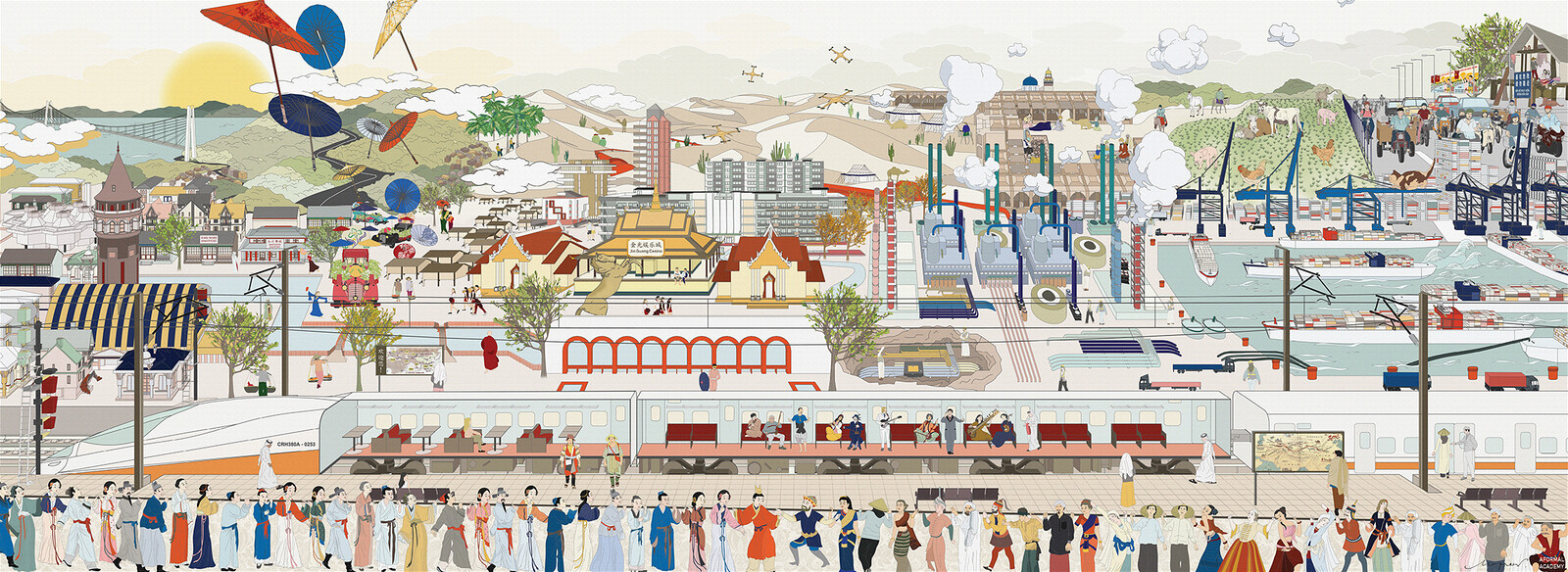

Chelnochnikov, or shuttle trading, in Khorgos. Image: Informburo, 2018.

While the small-scale crossings of the shuttle traders and shop tourists are characterized by long waits at the border control center, the monumental scale of cargo transfer along the SREB through Khorgos-Eastern Gate has yet to achieve the success promised by BRI rhetoric. To date, the volume of cargo along the SREB is bolstered by Chinese subsidies, which have been necessary to increase the economic viability of rail transit across Eurasia. Yet it was announced that, beginning in 2020, those subsidies will be reduced.17 The consequences of this for Khorgos and other SREB nodes are as of yet unclear.

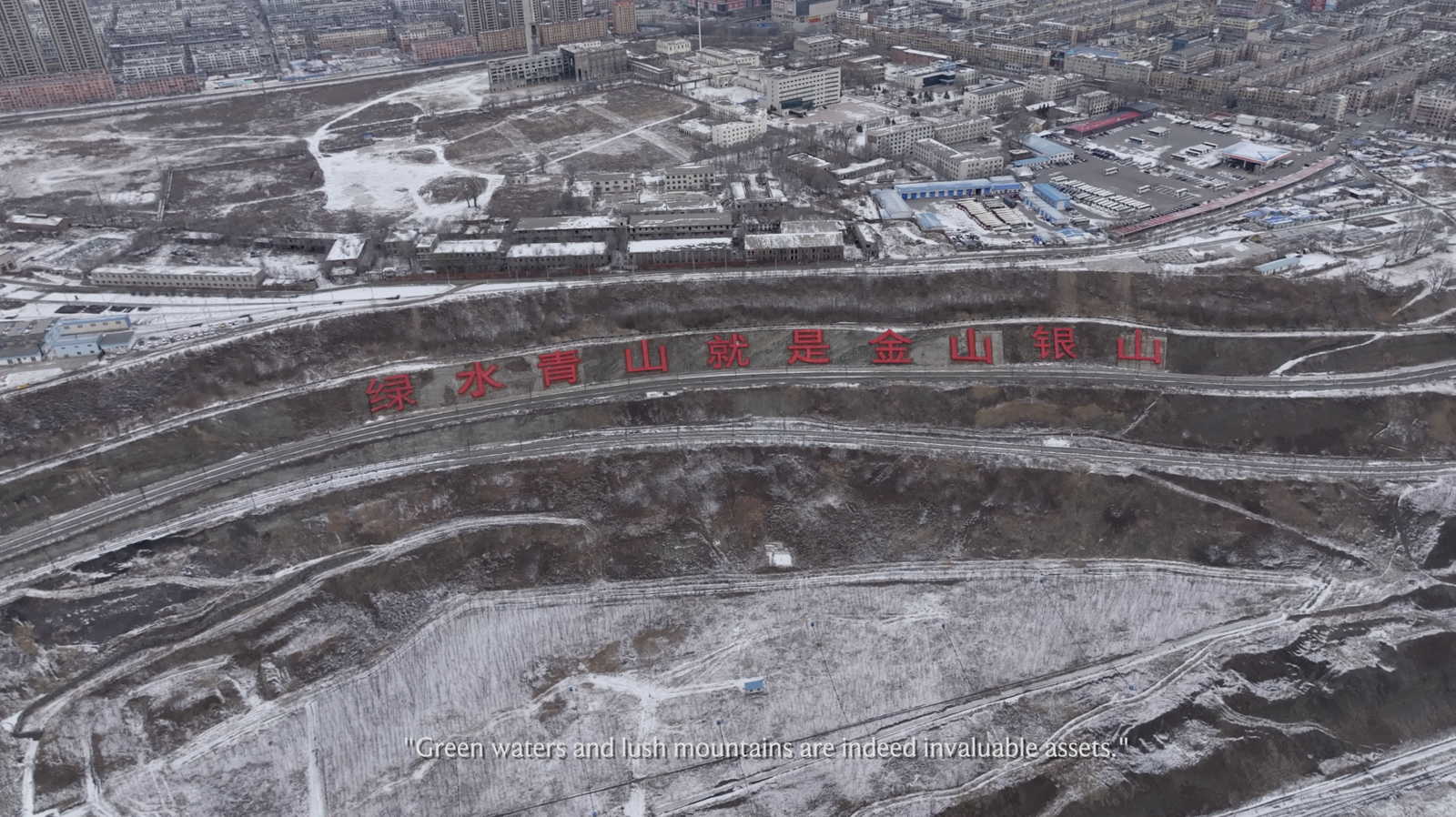

Elsewhere in Kazakhstan, the cessation of Chinese funds has caused large-scale infrastructural projects to stall. In Nur-Sultan, the capital, a curved concrete track built to support the city’s light rail network was poured before the Chinese Development Bank suspended the project loan, intersecting wiith several of the capital’s main thoroughfares and providing a sculptural reminder of the project’s collapse.

Will economic prosperity come if you build it a railway, or will it simply pass through? It remains to be seen if the economic promise of BRI investment in Khorgos will be realized. Without additional tenants and funding sources for Khorgos-Eastern Gate and the ICBC, it is unlikely that the current volume of cargo processing will support the operation and completion of the free trade zones as planned. This observation has already impacted the ongoing development of AECOM’s master plan, with the number of hotels reduced and other strategies put in place for programmatic diversification.

The construction of Khorgos and Nurkent also represents a major geographical shift in the focus of Kazakhstan’s urban development. Since the transition of the capital to the north in the late 1990s, Nur-Sultan has served as the urban image of Kazakhstani modernity, with vast sums of money spent on highly visible construction projects.18 Bolstering landlocked Kazakhstan’s connection to the networks of rail freight traversing the Eurasian landmass and opening new markets for the export of Kazakhstani goods and raw materials, the economic promise of the dry port and ICBC carries within it the potential to attract residents to the sparsely populated southeast. The construction of major urban centers in the south might destabilize Nur-Sultan’s geopolitical monopoly and offer new images of urbanity, all while heightening the visibility of political frictions occurring along the border.

A parallel address to the Indonesian Parliament was given by Xi Jinping the following month, announcing the Maritime Silk Road component of the BRI.

Bhavna Dave, “Silk Road Economic Belt: Effects of China’s Soft Power Diplomacy in Kazakhstan,” in China’s Belt and Road Initiative and Its Impact in Central Asia, ed. Marlene Laruelle (Washington, DC: George Washington University Central Asia Program, 2018), 97.

Nargis Kassenova, “China’s Silk Road and Kazakhstan’s Bright Path: Linking Dreams of Prosperity,” Asia Policy 24 (July 2017): 110–11.

Wade Shepard, “Khorgos: Why Kazakhstan is Building a ‘New Dubai’ on the Chinese Border,” Forbes, February 28, 2016, ➝.

Satellite view of SEZ Khorgos-Eastern Gates, Google Earth, September 2017, ➝.

As the number of cars per cargo train varies, this quantity is commonly described in terms of number of shipping containers. Shipping containers conform to two primary standardized lengths: twenty-foot and forty-foot, the latter of which is currently the most prevalent type. The twenty-foot equivalent unit, or TEU, commonly used to quantify rail shipments, derives from the smaller of the two standard shipping container lengths.

Prior to the construction of the SEZ, freight passing from China through Kazakhstan was transferred at the Dostyk Railway Station, initially constructed in the 1950s, approximately 290 km northeast of Khorgos. In addition to its larger and more contemporary facilities, the geographic position of Khorgos provides a more efficient transit route than that of the rail line passing through Dostyk.

The annual throughput of dry ports is small in comparison to that of maritime ports. By comparison, in 2017, China’s maritime port at Lianyungang handled a throughput of approximately 4.7 million TEUs.

Zhaniya Urankayeva, “Khorgos Dry Port to Process more than 500,000 Containers by 2020,” Astana Times, November 5, 2016, ➝.

This second break of gauge occurs at Brest, on the Belarus-Poland border.

Occurring under the auspices of the Nurly Zhol development program, it is part of a larger governmental push to diversify Kazakhstan’s national economy away from its reliance on extractive industries.

Actual city planning, in this sense, amounted to a notation indicating that the area between the northern extent of the ICBC and Khorgos-Eastern Gate would be developed into microdistricts at some future phase of construction. AECOM, “Summary Technical and Economic Report for Khorgos” and author’s email correspondence with member of the master planning team.

The Horgos City Master Plan for the period of 2010 to 2020 projected that that population figure would increase to 160,000 by the end of the planning period. “Horgos City Land Use Master Plan (2010-2020): Adjustment and Improvement Text,” Horgos Municipal Government, June 22, 2016, ➝.

Only one city, the former capital Almaty, has a population of over one million residents, with the majority of the nation’s other large metropolitan centers coming in between 100,000 and 300,000 residents.

Sebastien Peyrouse, “Chinese Economic Presence in Kazakhstan: China’s Resolve and Central Asia’s Apprehension,” China Perspectives 3 (July 2008): 37.

InformBuro, “‘Hesuny’ na Khorgose” (“Carriers in Khorgos”), YouTube video, April 15, 2018, ➝.

The subsidy reduction was dicussed in a panel alongside the 2019 European Silk Road Summit: Erik Groot Wassink, Rob Brekelmans, and Marjorie van Leijen, “RailFreight Webinar New Silk Road—Bubble or Here to Stay,” European Silk Road Summit, YouTube video, October 18, 2019, ➝.

Known by a series of names, including Aqmola, Tselinograd, and Astana, the capital was renamed Nur-Sultan following the resignation of President Nursultan Nazarbayev in March 2019.

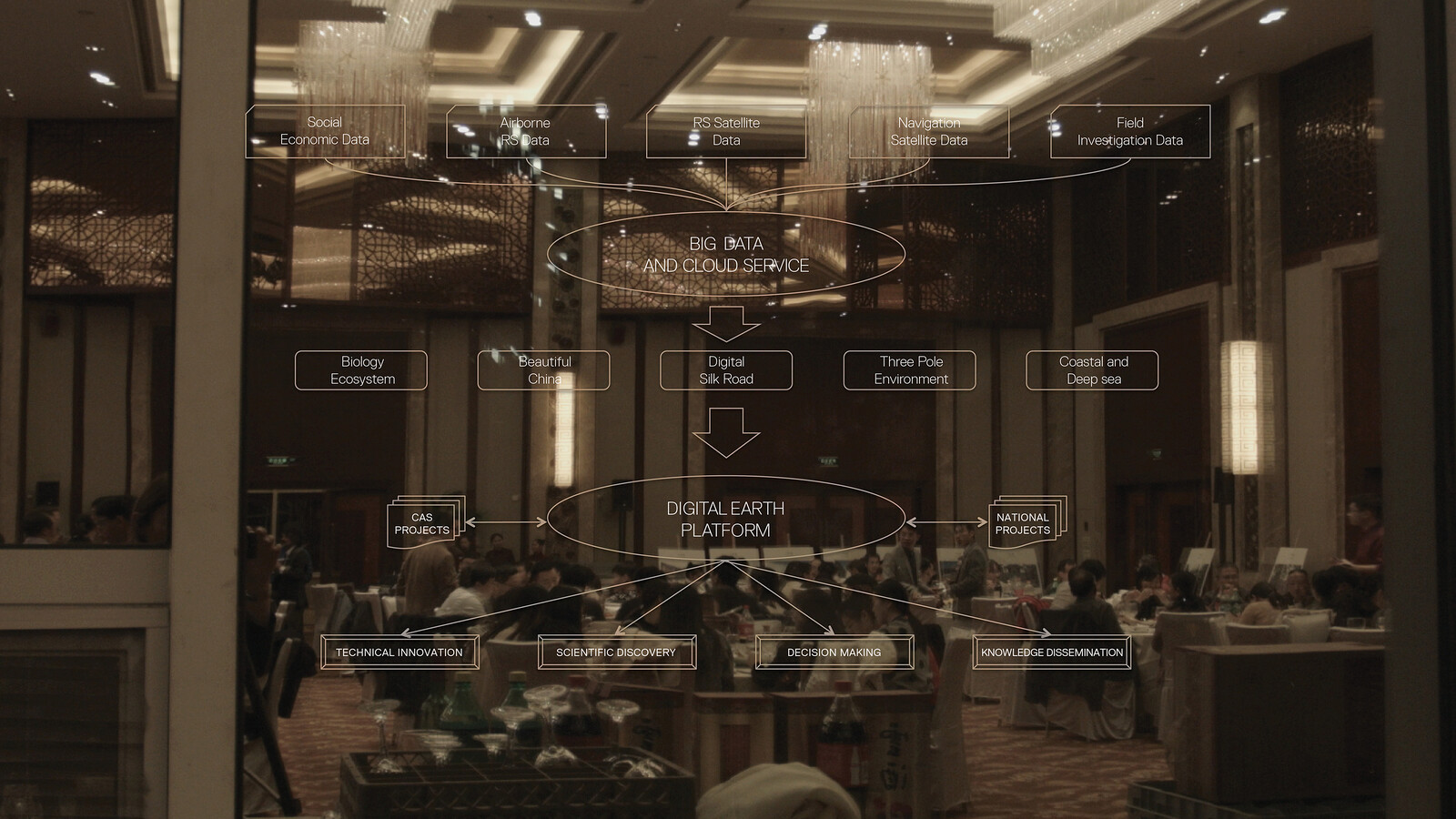

New Silk Roads is a project by e-flux Architecture in collaboration with the Critical Media Lab at the Basel Academy of Art and Design FHNW and Noema Magazine (2024), and Aformal Academy with the support of Design Trust and Digital Earth (2020).