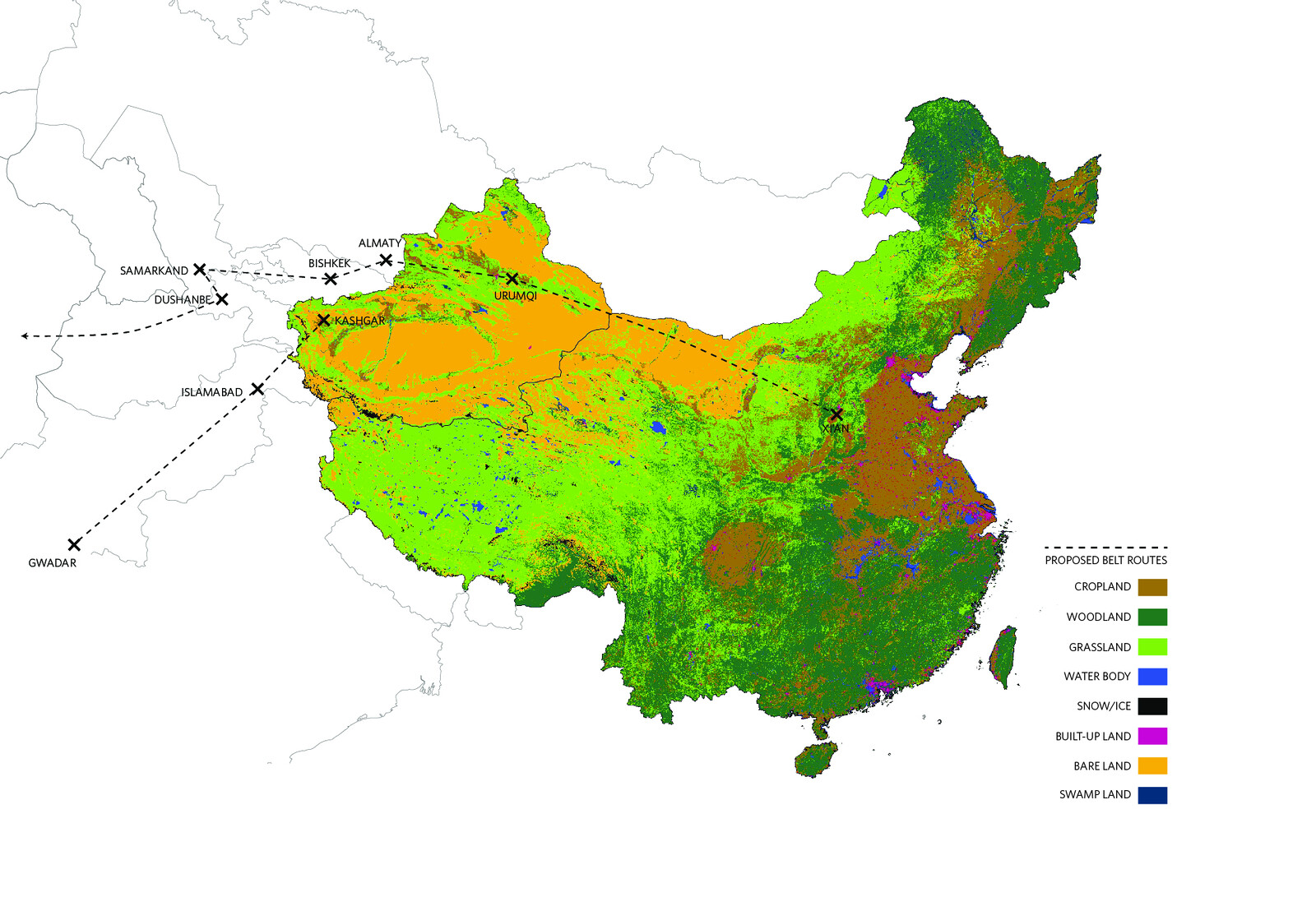

The “strategic invisibility” of desert spaces accommodates the pursuit of activities out of public view and beyond the realm of judicial and civic oversight. Hidden in the desert territory of Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region (Xinjiang) in northwest China are massive, high-security compounds currently imprisoning over a million people. The Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), which aims to mimic the transcontinental trade economy established along the original Silk Road, depends upon Xinjiang’s longstanding geostrategic role as a bridge between mainland China, Central Asia, Europe, and, eventually, Africa. The People’s Republic of China is exploiting the region’s geographic remoteness, cultural isolation, and the insidious discourse of the global War on Terror to justify and obscure the control, mass surveillance, and internment of its minority-Muslim citizenry.

The internment of China’s Muslim-minority populations in Xinjiang is one of numerous examples from across the globe of how the strategic invisibility afforded by desert landscapes has enabled an infringement on human rights to forward a certain geopolitical agenda. The commonly held, but fundamentally false, perception of deserts as expanses of desolate and empty spaces has allowed governments, institutions, and private enterprises alike to exert intensive control over these territories, often with little regard for long-term socio-environmental consequences. In the case of Xinjiang, perceptions of the region as empty and without value has resulted in transformations of the physical landscape and associated social structures over the last decade. Despite the massive scale and rapid rate at which these changes have been occurring, restricted access to and documentation of the area—especially the “re-education” camps—makes the region’s invisibility altogether more profound.

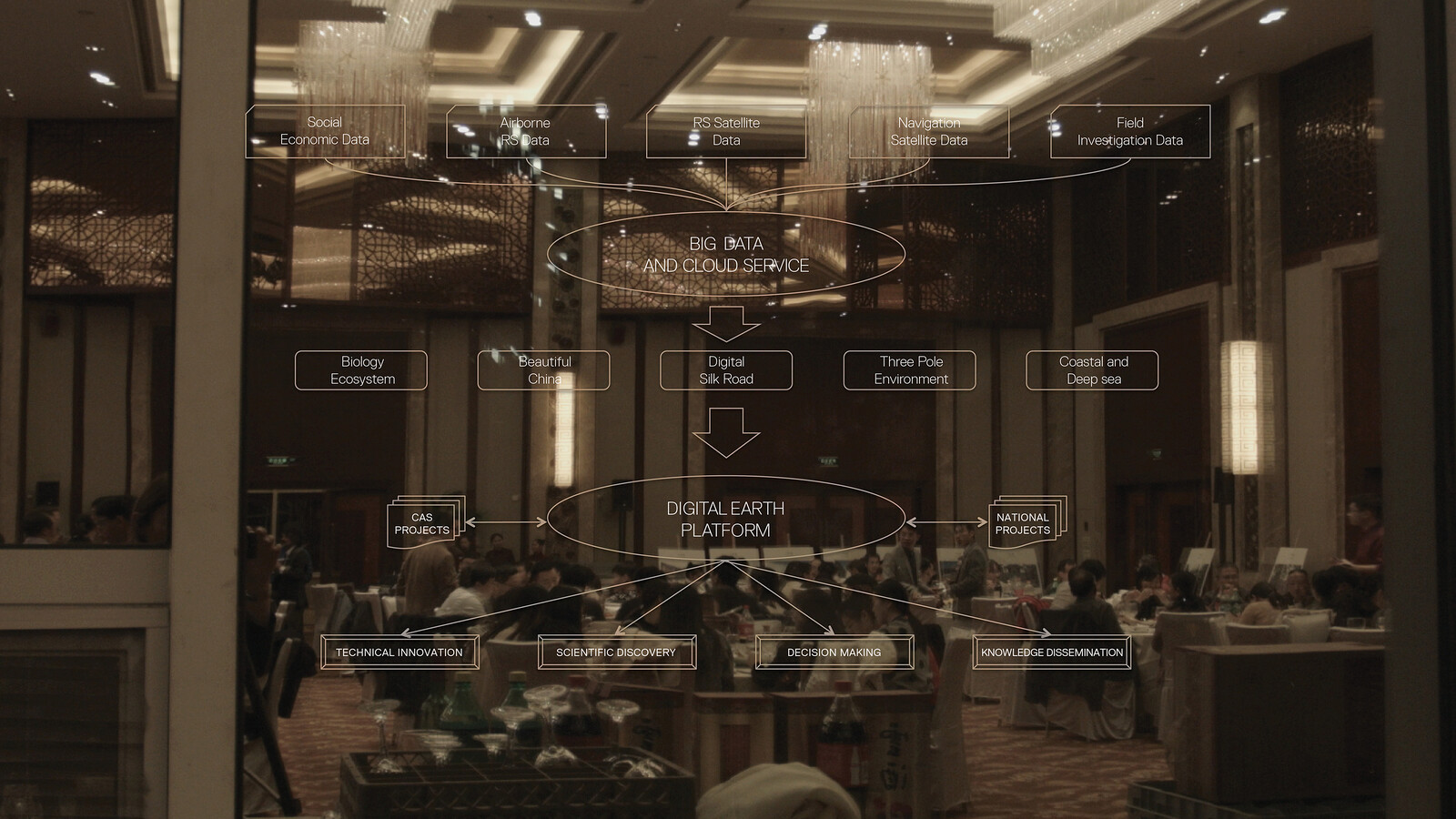

Maintaining control over Xinjiang’s territory and population is a critical element of the Communist Party of China’s (CCP) recent intentions to capitalize on the region’s economic potentials. Xinjiang is a vital geography in China’s global ambitions, and the Uyghurs’ cultural differences and separatist desires pose an existential threat to the state’s motives. While the exploitation of Xinjiang has taken place for centuries, the CCP has sought to further reaffirm control of the region as a strategic play in the country’s new global trade plan, the BRI. Ancillary to this has been the forced assimilation of Muslim-minority communities into mainstream Chinese culture and, in doing so, the suppression of dissent. While the BRI promotes extreme global connectivity, its success relies upon the continued invisibility of Xinjiang and its Uyghur people. Yet as the deliberate concealment of the state’s treatment of the Uyghurs becomes even more imperative to their objectives, the visibility of China’s foreign policy and economic agenda becomes more visible to the global community.1

The Strategic Invisibility of Xinjiang

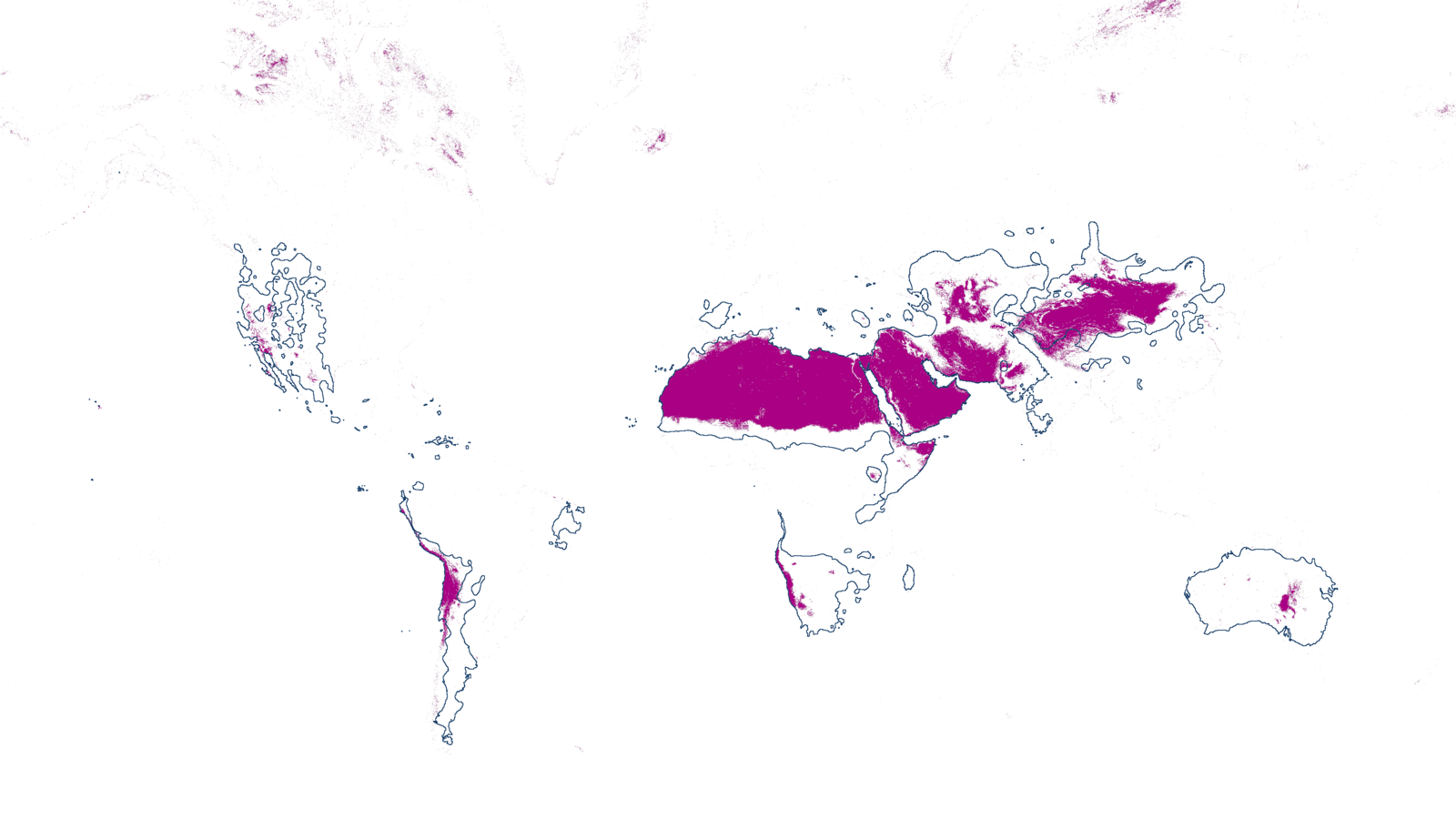

The strategic invisibility of desert landscapes like Xinjiang is predicated on descriptions of these spaces as empty, vacant, and lacking. Deserts are frequently drawn as voids, gaps, or blank spots on maps. But emptiness is not a geographical feature. Rather, it is a cultural construction and a graphic representation technique that has, both directly and indirectly, contributed to social, environmental, and economic exploitation of desert landscapes.2 Twelfth and thirteenth-century European definitions of the word “desert” directly translate to “wasteland”; the word first evolved from the late Latin desertum, meaning “thing abandoned.” This designation of the desert as an empty wasteland, which has well surpassed its European origins, suggests that it has no real social, environmental, or economic value.3 Historian Vittoria di Palma argues that the term “wasteland” itself is a category of land defined entirely by absence. She writes: “The emptiness that is the core characteristic of the wasteland is also what gives the term its malleability, its potential for abstraction; a vacant shell, it lies ready to include all those kinds of places that are defined in negative terms, identified by what they are not.”4 It is this correlation between deserts and wastelands that has helped contribute to perceptions that the desert is worthless and in need of transformation.

Environmental sociologist Valerie L. Kuletz makes the case that contemporary environmental science research continues to legitimize discourses of emptiness and wastelands by hierarchically organizing bioregional value according to productive capacity through the universally adopted Global Land Cover system.5 This categorization is partly the result of land cover and land use classification systems used by global governments to standardize processes for taxation and economic development purposes.6 Nearly all its categories classify lands through association with an industry, such as urban development or agriculture. The majority of Xinjiang is classified as “barren land” in the MODIS Land Cover classification dataset. Given that there is no “desert” or “arid” category in the MODIS dataset, “barren land” is defined as “land with limited ability to support life,” and is characterized by many features of desert landscapes—“dry salt flats,” “bare exposed rock,” “transitional areas,” and “mixed barren land.”7 Directly correlating economic productivity with vegetation, land cover categorization systems frame the value of these “barren” geographies in terms of their ability to be physically manipulated and repurposed into other, more productive land uses.

All of this belies the fact that Xinjiang contains oasis villages, towns, and cities where over 11 million Uyghur people live, work, and worship.8 The region is not only mineral rich in oil and gas but is also favorable to grazing livestock and the cultivation of cereals, melons, grapes, and the Aksu “sweetheart” apple—a billion-dollar industry based on a plant grown exclusively in Xinjiang.9 The ignorance of the Uyghur’s venerable and established culture requires strategic intervention.

For millennia, Xinjiang has been home to an ethnically Turkic people called the “Uyghurs,” who, while primarily nomadic, built impressive oasis cities with sophisticated agricultural techniques.10 At the height of the ancient Silk Road’s global influence, Xinjiang was a crossroads for culture and religion. At its trade centers in the oasis towns of Kashgar, Khotan, and Yarkhand, Uyghurs interacted with people from Persia, India, China, Mongolia, Turkestan, and Greece, and were introduced to Buddhism, Zoroastrianism, Christianity, and Manichaeism.11 In approximately 1000 CE, most of the region’s population converted to Islam, which today remains the primary religion of the region.12 The Uyghurs remained an autonomous population until the Chinese Qing imperial dynasty conquered Xinjiang in the mid-eighteenth century, bringing the region and the Uyghur people under Chinese leadership. Throughout the nineteenth century, Uyghurs made numerous, though unsuccessful, attempts to regain independence and reject colonization.13

In 1955, Xinjiang formally became a Chinese “autonomous” region, an administrative division defined through an affiliation with a particular ethnic minority.14 Today, Xinjiang remains strategically geolocated and forms China’s border with eight neighboring countries: Mongolia, Russia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Afghanistan, Pakistan, and India. It is China’s largest administrative region: at 1.6 million square kilometers, Xinjiang is approximately one-sixth of China’s land mass, equivalent in size to Great Britain, France, Germany, and Spain combined.15 Geologically, the region is significant for the Flaming Mountains, the Taklamakan Desert, the Turpan Depression, and the Tian Shan (“Heavenly Mountains”), all meaningful cultural landscapes to the local population. However, the region, along with the Uyghur community, has remained largely invisible from broader Chinese histories and Han culture. The continued separation of Xinjiang and its people from mainstream Chinese culture fortifies the concealment of activities pursued in the region.

Invisibility, Infrastructure, and the “Project of the Century”

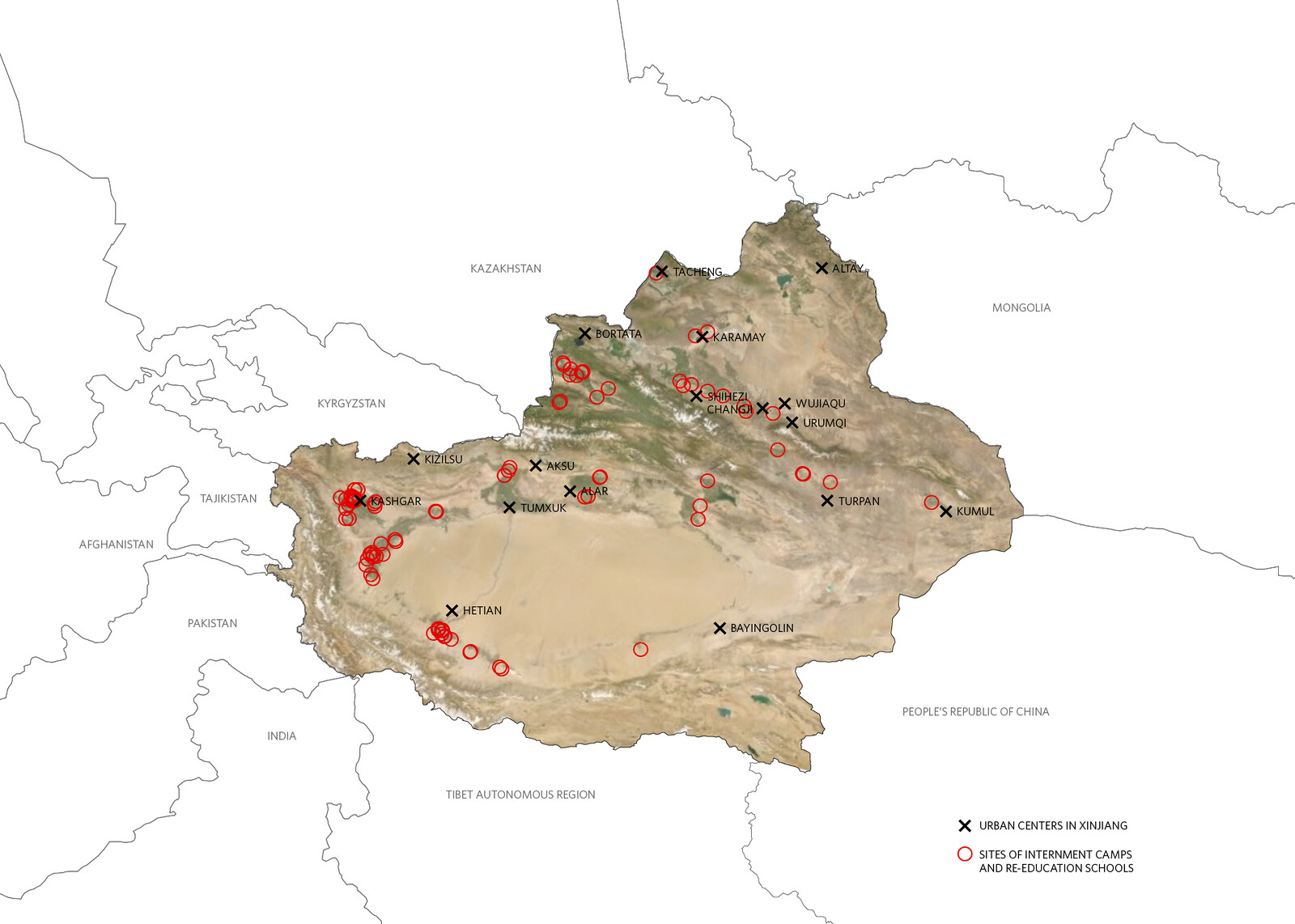

In January 2018, The Guardian reported that China had detained nearly 120,000 Muslim citizens in “re-education schools” deep in the Taklamakan Desert.16 More recent reports by both officials from the United Nations and independent researchers estimate that 1.5 million people have been detained so far, without due process and without consent.17 Satellite imagery confirms the existence of nearly one thousand massive, high-security compounds scattered throughout the region.18 Chinese officials claim that these camps, in coordination with the intensified mass surveillance and security in the region, are necessary responses to violent, anti-state episodes attributed to ethnic separatism, terrorism, and religious extremism.19 Critics have categorized the targeting of the Uyghurs, and the intention of eliminating their presence within the Chinese state, as cultural genocide.20 Scholar Adrian Zenz goes further to describe the efforts by the Chinese state as a “targeted political re-education effort that is seeking to change the core identity and belief system of an entire people.”21

In response to criticism, the Chinese government has remained adamant that the centers are voluntary educational centers that directly benefit the Uyghurs by providing language education and vocational training.22 In 2018, Hu Lianhe, a top Chinese official, told a United Nations human rights panel that “for those who are convicted of minor offences, we help and teach them vocational skills in education and training centers, according to relevant laws. There is no arbitrary detention and torture.”23 China’s UN Ambassador, Zhang Jun, said at the 2019 United Nations General Assembly that the accusations against China are “baseless,” a “gross interference in China’s internal affairs and deliberate provocation.”24 Zhang went further in stating: “Care for human rights is a hypocritical excuse employed by the United States to interfere in the internal affairs of other countries. By making relentless efforts to defame China on Xinjiang, the United States aims to undermine China’s stability and contain China’s development. Such malicious attempt [sic] will never work.”25 Yet evidence from satellite imagery exists of the architecture and infrastructure necessary to carry out such large-scale detention.

The Uyghur separatist movement and Uyghurs’ continued claim to this region as autonomous from the Chinese state have serious political and economic ramifications for the viability, stability, and international appetite for investment in BRI. The CCP’s dependence on Xinjiang as its geographic connection to the rest of the world poses uncertainties that threaten the future of the project.26 In order for the state to diminish this risk, political strategy necessitates that the Uyghur population must either be forced to fall in line or their challenge to state authority, if not defeated, must be made invisible.

Global “War on Terror” Discourse as Tool for Spatial Surveillance

After September 11, the Chinese government began to associate Uyghur political dissent in China with the burgeoning global “War on Terror” discourse. In November 2001, just weeks after 9/11, the CCP published an official document, “Terrorist Activities Perpetrated by ‘Eastern Turkistan’ Organizations and Their Links to Osama bin Laden and the Taliban,” positioning the Uyghur community as a major threat to national security.27 The document refers to the Uyghurs as “terrorists,” a notable shift from previous official party descriptions of them as “separatists.” Cultural anthropologist Sean Roberts writes: “It is likely that the state’s sudden claim of a Uyghur terrorist threat was less a response to new security concerns in the region than an attempt to justify existing policies suppressing Uyghur nationalism and religiosity by framing them in the discourse of global ‘War of Terror’.”28 In this context, certain human rights and legal protections could be considered null and void, providing justification for mass surveillance and internment of the region’s Muslim minorities.

The architect of such extreme actions against the Uyghur people and other Muslim minority communities in China is Chen Quanguo.29 His leadership as Xinjiang’s Communist Party Secretary has manifested in the drastic physical transformation of the region’s landscape and urban centers. Under Chen, Xinjiang was transformed into a mass security state, making it one of the most heavily fortified and policed regions in the world, paradoxically resulting in an enormous amount of focus being placed on the region by state officials and security personnel.30 In cities like Urumqi, Kashgar, and Hotan, public and private space are continually surveilled and monitored through advanced, intrusive policing systems. A dense grid of checkpoints, police stations, armored vehicles, and high-definition cameras define the current urban form of cities within Xinjiang.31 Facial recognition software tracks nearly every person on the street.32 Police-related jobs increased to over 90,000 in 2016, from just over 5,000 a decade earlier.33 Nearly 95% of these new positions were created to work in the extensive network of 7,500 new police stations in Xinjiang.34 Further, the seemingly omnipresent surveillance system is a new type of civic infrastructure in Xinjiang that revolves around fear tactics and punishment. The pervasive fear of being identified as a terrorist and being sent to the camps has had a drastic effect on urban centers. Once thriving cities and towns, many of Xinjiang’s population centers are now ghost towns with empty streets, shuttered businesses, and locked mosques.

In 2015, the National People’s Congress passed counter-terrorism legislation that criminalized Uyghur expression of dissent or religiosity, and has encouraged both the police and ordinary citizens to view many Uyghur cultural traditions as signs of terrorism or extremism.35 The legislation also included an initiative to “re-educate” the Uyghur population. According to the Chinese government, re-education camps are intended as poverty-alleviation measures that provide opportunities for vocational skills training and language assimilation, a justification that makes any Uyghur or ethnic minority vulnerable to encampment.36 In August 2019, China’s Ambassador to the United Nations, Yu Jianhua, claimed that China had helped lift twenty million people out of conditions of poverty in the last five years through economic progress.37 However, Uyghurs and other ethnic minorities are forced into these programs without consent and without any indication or judicial process articulating why they are being imprisoned and when they will be released. Those who have been through re-education claim that they were made to memorize patriotic texts, speak exclusively in Mandarin, confess their “faults,” denounce their religious traditions and culture, and report on the activities of fellow internees. Those who do not follow orders or fail to adequately appease the guards are beaten, placed in solitary confinement, or deprived of food and sleep.38

Despite the CCP’s denial that these are heavily policed internment camps, Adrian Zenz has compiled and published a body of governmental documents that provide evidence of the existence and oppressive purpose of these compounds. Zenz’s research shows that elements listed within CCP bids for infrastructure development projects in the region are inconsistent with education facilities. Instead, they are components most often associated with carceral architecture. For instance, one bid is titled “Convert former office building into transformation for education center.” However, the descriptions focus almost exclusively on detainment and policing infrastructure.39 Most of these governmental bids mandate the installation of comprehensive security features that turn existing facilities into prison-like compounds; they call for surrounding walls, barbed-wire fences, reinforced security doors and windows, surveillance systems, secure access systems, watchtowers, guardrooms, police stations, and facilities for armed police forces. Zenz has estimated that, as of 2019, there are at least a thousand of these camps, with up to 1.5 million people held within them, and almost all located in remote and unseen parts of Xinjiang.40 Most of these compounds have been identified by scouring satellite images of Xinjiang produced by software like Google Earth. If Zenz’s estimates are accurate, maintaining the invisibility of this extensive constellation is remarkable.

Uyghur activist Shawn Zhang uses Google Earth imagery to link CCP bid documents with compounds and demonstrate the rapid expansion of facilities on site. In one example, satellite imagery showed a location contained only one building on March 6, 2017. On April 26, a Request for Proposal was published, and one month later, on May 26, construction had begun on the site. By November 30, an entire compound of buildings was nearly complete. In September 2018, additional buildings were constructed, continuing the methodical expansion of the site’s facilities. Architectural components built on site include high barbed-wire fences and watchtowers encircling the “education” center.41 In addition to the built projects, there has been a wave of job positions advertised throughout China to help run the education and training centers, but often the job descriptions and requirements fail to have any relationship to vocational skills training: instead, they seek applicants who possess a military background or police training. Moreover, prospective teachers did not need to prove any specific degrees or documented skills.42

These aerial images, taken between 2016 and 2019, show over time how the landscape is fundamentally transformed by the construction of the camp architecture, transportation networks, and security infrastructure necessary to conceal the imprisonment of the Uyghur population. Aerial imagery produced by Google Earth and Maxar Technologies.

Strategic Visibility

In November 2019, hundreds of pages of official, internal CCP documents were leaked to the New York Times. These documents were the first piece of concrete evidence that the very top officials of the Chinese state have mandated this system of repression and imprisonment, and that the ambitions of such a system are to suppress the Uyghurs’ religious and cultural freedom. The documents reveal that, in April 2014, President Xi Jinping gave a series of internal speeches outlining a crackdown against the Uyghurs in Xinjiang and calling for a unified “struggle against terrorism, infiltration, and separatism” using the “organs of dictatorship” and showing “absolutely no mercy.”43

Despite this evidence that actions pursued in the region have violated basic human rights, most global powers have remained silent in condemning China for its treatment of the Uyghur population. Such reticence is largely attributable to the entanglements of the global economy resulting from China’s dominance in industry and manufacturing, which is only likely to increase as the Belt and Road Initiative further strengthens China’s position at the epicenter of global trade. Linking the economic benefits of the BRI with the human rights violations of internment camps has been a shrewd political strategy: it has forced global powers to choose between the promise of economic growth and publicly denouncing human rights violations.

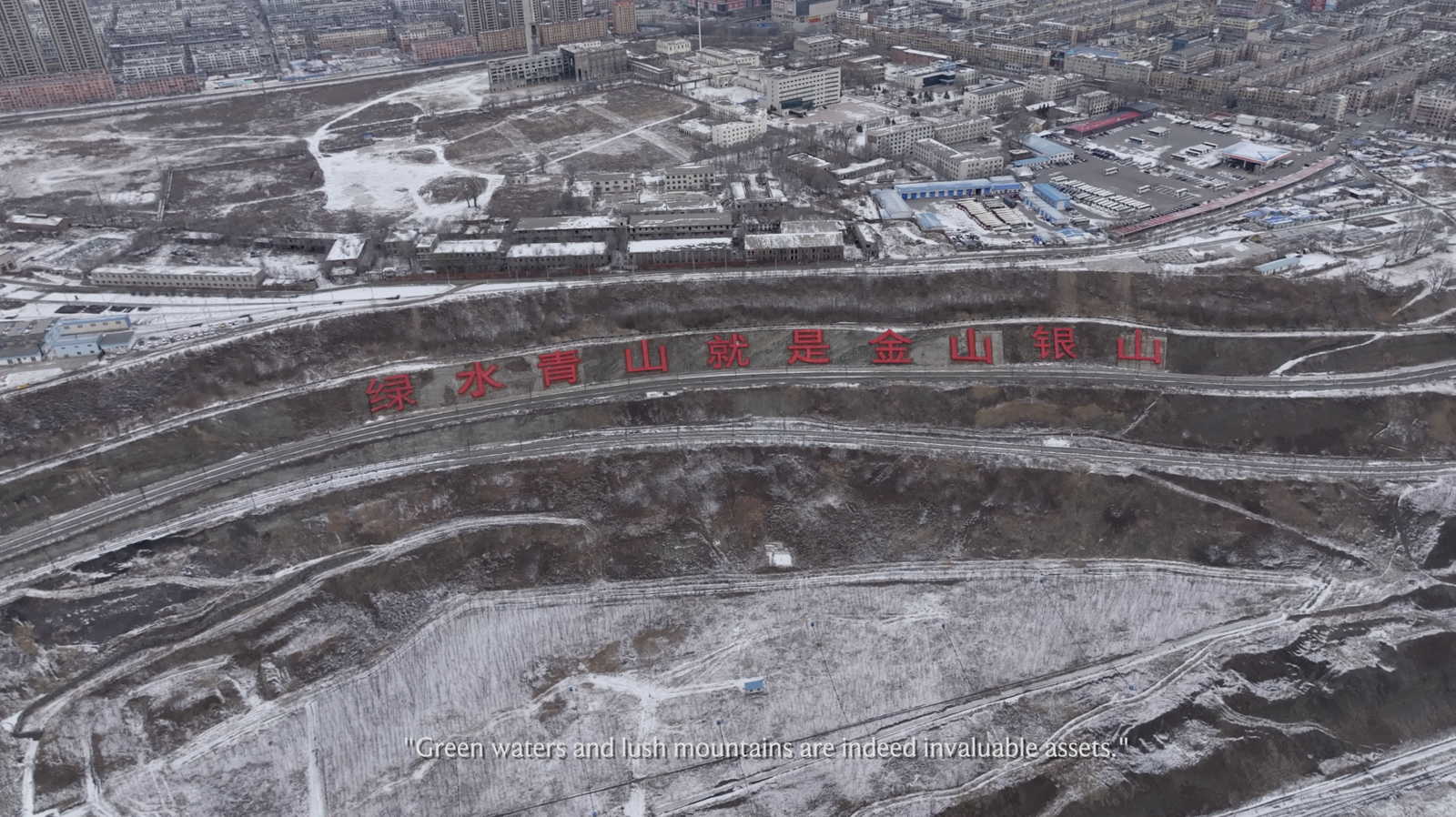

Xinjiang reveals the potency and power that perceptions of landscapes have on policy with direct social and spatial ramifications. The strategic invisibility of Xinjiang’s desert landscapes and the human rights violations that continue to occur in them serve the political and economic agenda of the People’s Republic of China. Specifically, the BRI’s visibility hinges on the continued invisibility of the Uyghurs. Simultaneously, the construction of the BRI through Xinjiang fundamentally inverts the perception of the region as empty and undeveloped, erecting new infrastructural, urban, and social systems that uphold China’s global vision. In this way, the BRI project as a whole is about strategic visibility insofar as it draws attention to regions in order to produce a new set of perceptions and opportunities for prosperity, at all costs.

It is important to note that it is precisely because of the region’s low population density and remote location that these events are able to take place. Despite increasing suspicion of human rights violations, there is limited documentation and evidence. China has been highly effective at both denying access to sites and controlling the narrative about Xinjiang to its own citizens, such that most people within mainland China are complete unaware of what is happening to the Uyghurs and other Muslim minority groups. If these same actions were pursued in high-density urban areas, keeping them hidden and secret would be nearly impossible, but the geographic remoteness of the region and the successful public intimidation of the Uyghurs keep these violations invisible. As such, I am deeply indebted to the dedicated scholarship of Adrian Zenz and Shawn Zhang, who have each painstakingly worked to expose this atrocity with almost no official data and without physical access to Xinjiang.

See Wendy Harding, The Myth of Emptiness and the New American Literature of Place (Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 2014); Catrin Gersdorf, The Poetics and Politics of the Desert: Landscape and the Construction of America (Amsterdam: Rodopi, 2009).

It is important to note that many non-European cultures have viewed deserts as spaces of rich culture and ecologies. The most prominent examples are the Hohokam people of the southwestern United States, the Rajasthani pastoralists in the Indian subcontinent, and the ancient Egyptians.

Vittoria Di Palma, Wasteland: A History (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2014), 3–4.

Valerie L. Kuletz, The Tainted Desert: Environmental and Social Ruin in the American West (New York: Routledge, 1998), 13.

Global land cover datasets have been used since the 1970s. Since the 1990s, NASA and the USGS have produced the most comprehensive and widely accepted datasets that are used throughout the world by governments and institutions to track and monitor land cover change. G. Gutman et al., “Towards Monitoring Land-Cover and Land-Use Changes at a Global Scale: The Global Land Survey 2005,” Photogrammetric Engineering and Remote Sensing 74, no. 1 (2008): 5; Peng Gong et al., “A New Research Paradigm for Global Land Cover Mapping,” Annals of GIS 22, no. 2 (April 2, 2016): 87–102.

James R. Anderson et al., “A Land Use and Land Cover Classification System for Use with Remote Sensor Data,” (Washington, DC: United States Geological Survey, Department of the Interior, 1976), 18.

Stanley Toops, “Spatial Results of the 2010 Census in Xinjiang,” Asia Dialogue, March 7, 2016, ➝.

Nick Holdstock, China’s Forgotten People: Xinjiang, Terror and the Chinese State (New York: I.B. Tauris, 2015), 13; Xinhua, “Man-Made Oasis: Xinjiang’s ‘Green Wall’ Fights Expanding Desert,” China Daily, October 19, 2018, ➝.

James A Millward, Eurasian Crossroads: A History of Xinjiang (New York: Columbia University Press, 2009), 43.

Rian Thum, The Sacred Routes of Uyghur History (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2014), 17.

Valerie Hansen, The Silk Road: A New History with Documents (New York: Oxford University Press, 2016), 199.

James A. Millward, “Historical Perspectives on Contemporary Xinjiang,” Inner Asia 2, no. 2 (2000): 130.

In principle, this is meant to give members of that minority rights not afforded to others. There are five autonomous regions in China that are each associated with one or more ethnic minority: Zhuang Autonomous Region, Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region, Tibet Autonomous Region, Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region, and Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region. It is important to note that despite the acknowledgement of ethnic diversity, these populations have been substantially disenfranchised socially, politically, and economically. Tibetans are perhaps the most well-known example, but they are by no means the only ones to have experienced such marginalization. It is important to note that Tibet’s status as an Autonomous Region is a delineation that has been ascribed by the Chinese state but is highly contested by Tibetans and much of the international community, who believe that Tibet is a sovereign nation.

Millward, Eurasian Crossroads, 4.

Tom Phillips, “China ‘Holding at Least 120,000 Uighurs in Re-Education Camps,’” The Guardian, January 25, 2018, ➝.

Adrian Zenz, “Brainwashing, Police Guards and Coercive Internment: Evidence from Chinese Government Documents about the Nature and Extent of Xinjiang’s ‘Vocational Training Internment Camps,’” Journal of Political Risk 7, no. 7 (July 2019), ➝.

See Zenz, “Brainwashing, Police Guards and Coercive Internment”; Ben Mauk, “Can China Turn the Middle of Nowhere into the Center of the World Economy?,” The New York Times, January 29, 2019, ➝.

Rémi Castets, “What’s Really Happening to Uighurs in Xinjiang?,” The Nation, March 19, 2019, ➝.

Nick Cumming-Bruce, “U.N. Panel Confronts China Over Reports That It Holds a Million Uighurs in Camps,” The New York Times, August 10, 2018, ➝.

Chris Buckley and Amy Qin, “Muslim Detention Camps Are Like ‘Boarding Schools,’ Chinese Official Says,” The New York Times, March 12, 2019, ➝.

Despite Xinjiang only accounting for approximately 1.5 percent of the country’s total population, 21 percent of all arrests in 2017 were made in Xinjiang, according to the human rights advocacy group Chinese Human Rights Defenders. Lily Kuo, “China Denies Violating Minority Rights amid Detention Claims,” The Guardian, August 13, 2018, ➝.

Reuters, “China Warns US: Criticism of Uighur Detentions Is Not ‘helpful’ for Trade Talks,” The Guardian, October 30, 2019, ➝.

Jun Zhang, “Statement by Ambassador Zhang Jun on Human Rights during Dialogue with Chairperson of CERD at Third Committee of United Nations General Assembly,” Permanent Mission of the People’s Republic of China to the UN, October 30, 2019, ➝.

The Uyghur community believes that the Chinese government unjustly colonized them and, as a result, they have actively contested their control by the Chinese government. They have fought for their independence from the Chinese state unsuccessfully since the Qing imperial dynasty conquered them in the eighteenth century.

Communist Party of China, “Terrorist Activities Perpetrated by ‘Eastern Turkistan’ Organizations and Their Links with Osama Bin Laden and the Taliban,” Permanent Mission of the People’s Republic of China to the UN, November 29, 2001, ➝.

Sean R. Roberts, “The Biopolitics of China’s ‘War on Terror’ and the Exclusion of the Uyghurs,” Critical Asian Studies 50, no. 2 (April 2018): 238.

It should be noted that prior to his post in Xinjiang, Chen had been Party Secretary of Tibet (2011-2016) where his successful policies to suppress dissent were widely lauded by the Chinese Community Party. Many of his tactics in Tibet have been instituted and intensified in Xinjiang.

Adrian Zenz, “‘Thoroughly Reforming Them Towards a Healthy Heart Attitude’: China’s Political Re-Education Campaign in Xinjiang,” Central Asian Survey (September 2018): 3.

James A. Millward, “What It’s Like to Live in a Surveillance State,” New York Times, February 3, 2018, ➝.

Chris Buckley and Paul Mozur, “How China Uses High-Tech Surveillance to Subdue Minorities,” New York Times, May 22, 2019, ➝.

Adrian Zenz and James Leibold, “Chen Quanguo: The Strongman Behind Beijing’s Securitization Strategy in Tibet and Xinjiang,” China Brief 17, no. 12 (2017): 18.

Zenz and Leibold, “Chen Quanguo,” 18.

Roberts, “The Biopolitics of China’s ‘War on Terror’ and the Exclusion of the Uyghurs,” 246.

Meng Jianzhu, secretary of the CCP and Legal Affairs Commission, said in 2018: Through “religious guidance, legal education, skills training, psychological interventions, and multiple other methods, the effectiveness of transformation through education must be increased, thoroughly reforming them towards a healthy heart attitude.” Zenz, “‘Thoroughly Reforming Them towards a Healthy Heart Attitude,’” 15.

See Cumming-Bruce, “U.N. Panel Confronts China Over Reports That It Holds a Million Uighurs in Camps.”

Zenz, “‘Thoroughly Reforming Them towards a Healthy Heart Attitude,’” 12.

Zenz, “‘Thoroughly Reforming Them towards a Healthy Heart Attitude,’” 12.

Stephanie Nebehay, “1.5 Million Muslims Could Be Detained in China’s Xinjiang,” Reuters, March 13, 2019, ➝.

Shawn Zhang, “Satellite Imagery of Xinjiang ‘Re-Education Camp’ Number 01,” Medium, October 1, 2018, ➝.

Zenz, “‘Thoroughly Reforming Them towards a Healthy Heart Attitude,’” 19.

Austin Ramzy and Chris Buckley, “‘Absolutely No Mercy’: Leaked Files Expose How China Organized Mass Detentions of Muslims,” New York Times, November 16, 2019, ➝.

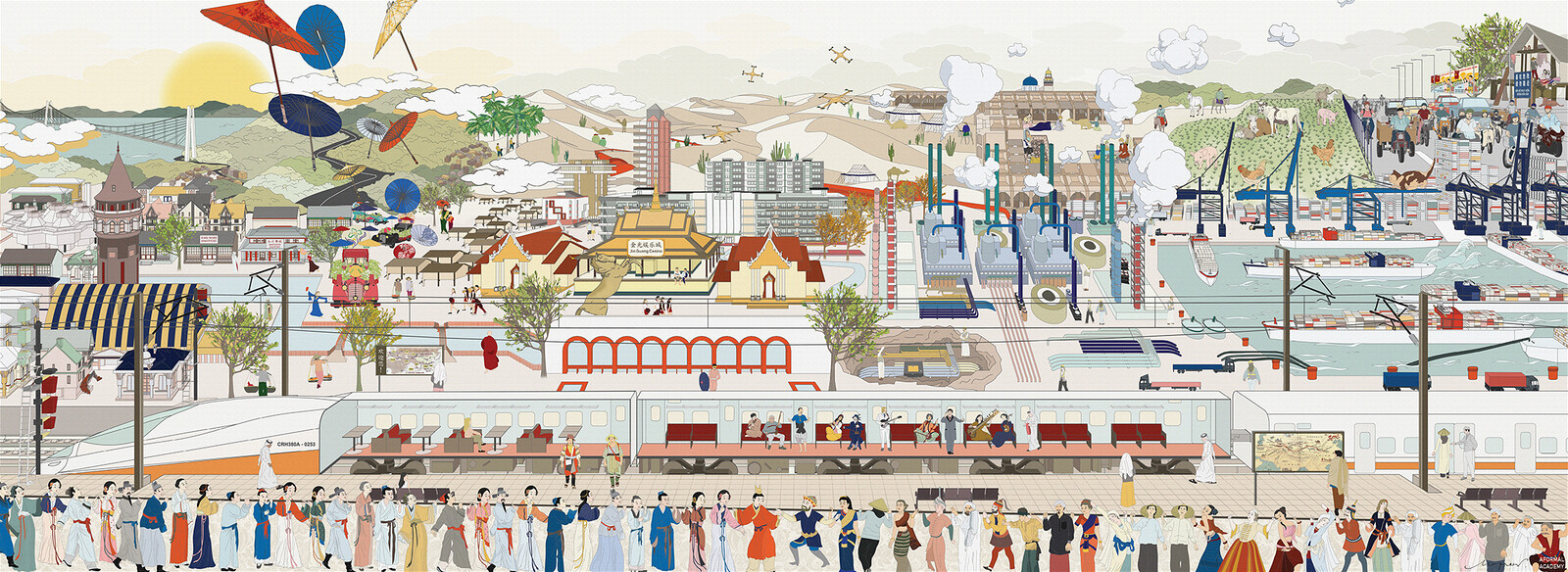

New Silk Roads is a project by e-flux Architecture in collaboration with the Critical Media Lab at the Basel Academy of Art and Design FHNW and Noema Magazine (2024), and Aformal Academy with the support of Design Trust and Digital Earth (2020).