There is a mud volcano on the periphery of Gwadar, a coastal town in Pakistan’s Balochistan province, locally known as “sumunder ki naaf,” or the belly button (umbilical cord) of the sea. For a long time, local people believed this was where the sea received its nourishment, just as they received theirs from the sea through fishing and trade. There was an intimate and reciprocal relationship between the sea and Gwadar, with sumunder ki naaf at its center. However, with the cartographic mapping conducted by colonialists and others, people came to realize that this was just one of a string of mud volcanoes dotted along the Mekran coast.1 It may no longer be the center of their world, but the volcanoes connect a region and a people together. Gwadar has long been an important free port in the Arabian Sea, strategically located for the shipping routes across the Indian Ocean connecting South Asia, the Gulf, and Northern Africa.2

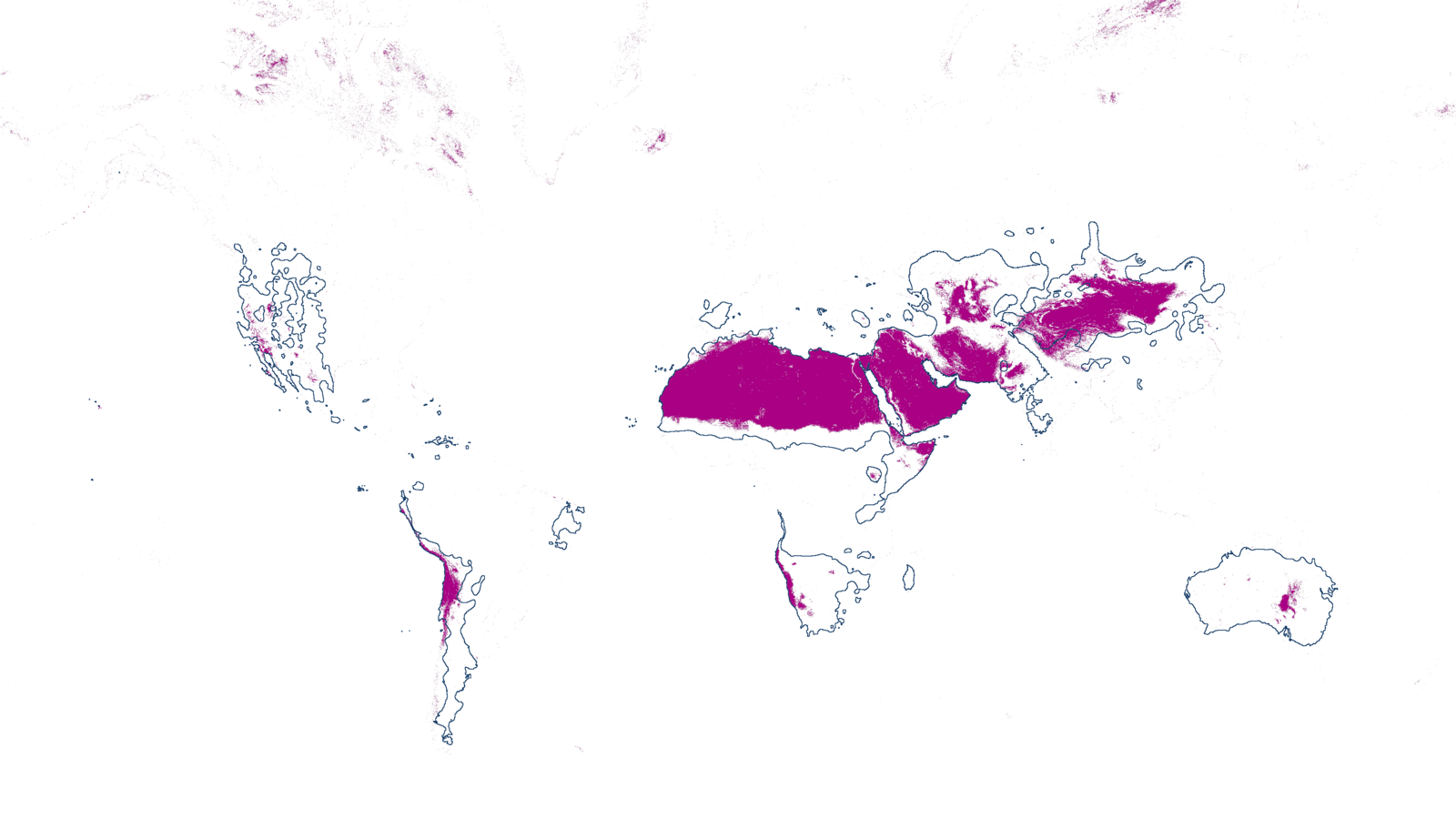

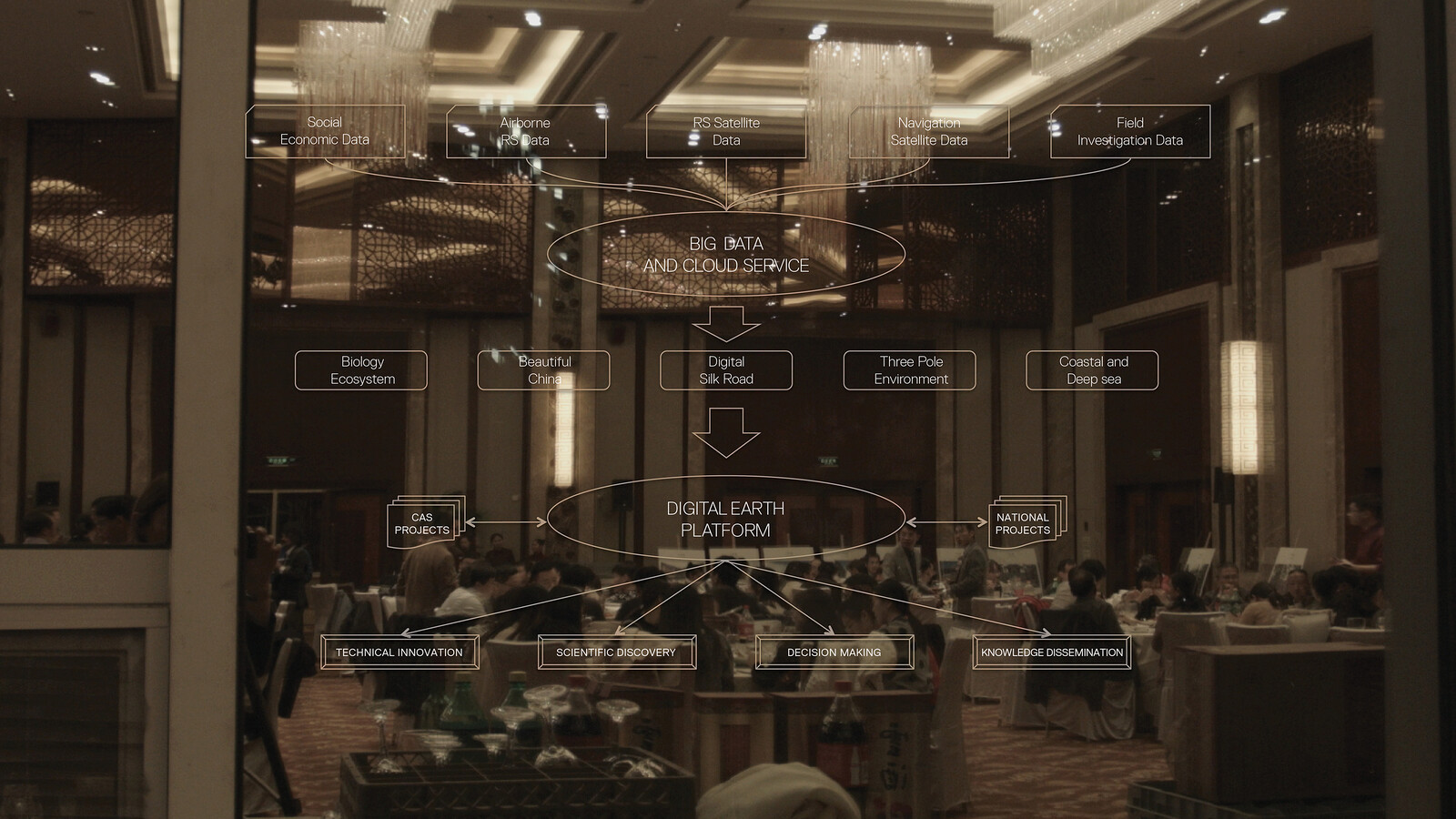

Some today consider Gwadar the center of a world again, but this time a very different world, one that is derived from the flow of logistics and capital. The newly operational Gwadar Port is the terminus point of the China–Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC). CPEC is an important link within the wider Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), as Gwadar Port is the only point connecting China’s Silk Road in Central Asia to the Maritime Silk Road in the Arabian Peninsula and Northern Africa. It is therefore considered a crucial hub, or the “jewel in the crown” of the BRI masterplan.3 This is also how Gwadar appears in the Pakistani national imaginary: as a potential new Dubai to be developed in a remote coastal town, where large-scale infrastructure will not only bring much needed investment and development to the region but also to the country. CPEC is, of course, only one small part of the wider BRI and Digital BRI project, but in the context of Pakistan it holds geopolitical and economic significance. With over $60 billion USD of investment planned over several years (2017-2030), its development consists of road, rail, and fiber optic projects as well as special economic zones and some agriculture.4

Infrastructural Imaginaries

These two worlds, one centered around sumunder ki naaf and the other around Gwadar Port, come together in estrangement through CPEC-related infrastructural development. A project as vast as CPEC, which was first announced in Pakistan in 2013, has been planned across successive governments, which have all embraced it unreservedly. Yet, there are some signs of dissent emerging, with rumors circulating of a belated recognition that the contracts signed with China are decidedly one-sided. The extractivist nature of Chinese investment ensures that all money lent to Pakistan is spent on Chinese goods and labor; a lesson that could easily have been learned through its involvement in various African countries.5 The growing concern around CPEC in Pakistan is perhaps highlighted most starkly with the first question on the official government website’s FAQ page: “Is CPEC becoming another East India Company?”

Anxieties around China’s neocolonial ambitions are further exacerbated by the Pakistani state’s own colonial attitude towards the province of Balochistan, where a secessionist insurgency is currently coming to an end.6 Spanning Pakistan and Iran, the historical area of Balochistan is cut by a colonial border drawn across a landscape viewed as forbidding to Western eyes. Up until the establishment of the Goldsmid Line in 1871, which settled the border between Persia and British India, the lines drawn across Balochistan waxed and waned according to tribal rivalries and external interference. Thus, to think of Balochistan as one homogenous space is to misunderstand it: the Mekran region, which borders the Arabian Sea, is culturally and physically separated from northern Balochistan, where the provincial capital of Quetta is situated. Mountains separate the north from the south, meaning that, historically, these areas have not had much connection. In fact, the strongest connections in the Mekran region are across the water towards Oman, owing to its free port status, and with other Baloch areas across the border in Iran. For many Baloch, the Chinese are only the latest in a series of colonial masters.

Balochistan is currently in the midst of a rapid urbanization that is reshaping people’s relationship with the land and the sea, as well as leading to the rise of a new middle class that is evolving from traditional tribal structures. Yet, rather than considering how any of this may relate to the people who live and work there, and whose lives are to be most affected, the region’s history and the unequal relationship with China has meant that the discourse on CPEC in Pakistan and beyond either revolves around its macroeconomic advantages and disadvantages, or is framed through questions of security in wrangling over the corridor’s exact route.7 On the ground stories and an understanding of what is happening at the southern end of CPEC in Gwadar and its surroundings are sparse.

The image of the mud volcano and CPEC appear to be conflicting in many ways, but they overlap and intertwine in terms of the aspirations, objectives, and practices of actors and stakeholders involved. One example is the way in which the rhetoric on development around CPEC-BRI is fueled by the promise of prosperity (mostly economic) and is shared by multiple actors and stakeholders including local communities. As the Gwadari fisherfolk tell those who will listen, their decade-long struggle against the port and now CPEC-related construction has not been against “development” as such. Rather, they share the same hope for better livelihoods and access to education and healthcare as everyone else. However, the materialization of these imaginaries through state and non-state projects, actions, laws, and strategies not only alienates and exploits local communities and landscapes, but also fuels anxieties and conflicts.

As capital flows through Gwadar, the surrounding landscape is being molded and sculpted in its wake. This restructuring of material and social worlds is both violent and silencing. In Gwadar, it is the silences that speak more to the effects of the infrastructural imaginary than the loud utterances of speculative development, because, in many ways, this has all been seen before: the shiny skyscrapers, the standardized planning, promises of secure and smart cities … How then might we attune ourselves to the silences that are being perpetuated across multiple registers in order to engage in more locally embodied concerns? A site of contestation within the infrastructural development has been the evolving Gwadar Development Authority (GDA) masterplan designed in consultation with the Chinese government. It transcends immediate ways of knowing the landscape and engages instead with distant elsewheres, such as Shenzhen or Dubai, rendering existing lives and their relationships to the environment irrelevant.

Reorientation

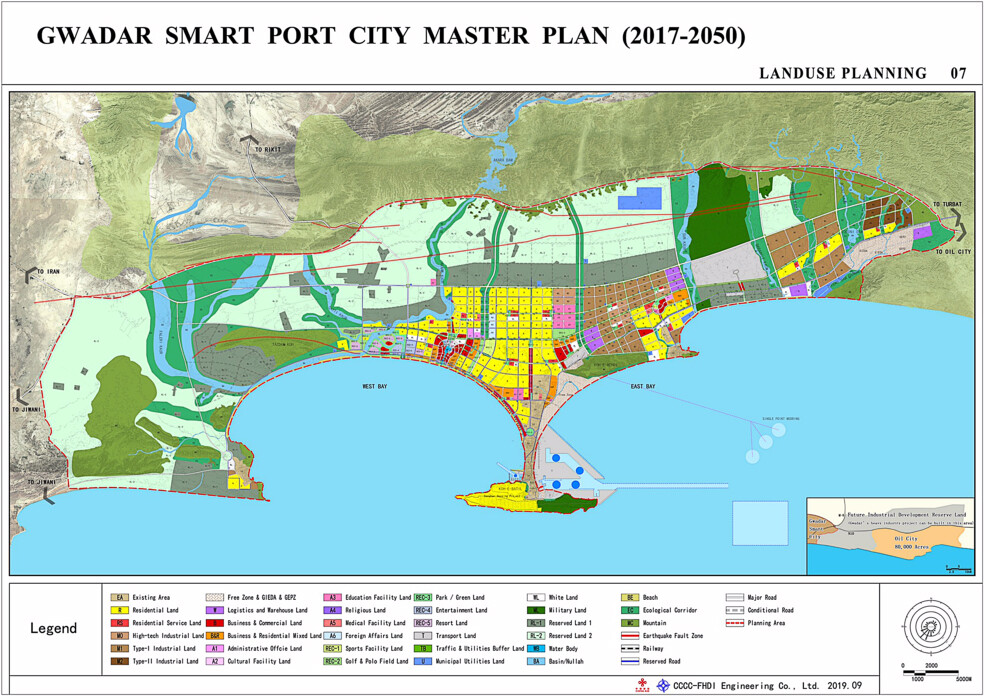

The first masterplan for Gwadar was made in 2002 by the state-owned NESPAK (National Engineering Services Pakistan), and there have been several iterations since. The most recent, officially titled “Gwadar Smart Port City Masterplan,” is the most comprehensive, and was approved by federal and provincial governments in late 2019. Divided into several zones, such as industrial, residential, and commercial, it also includes a free trade zone and land reserved for military use. The planned city is approximately fifteen times the size of the existing town, and spreads far beyond the thin strip of land opening out into a hammerhead that constitutes Gwadar Peninsula. The hammerhead is formed of rocky outcrops that serve as natural wind barriers. Although not inhabited, it is an important recreational area, used for festivals and gatherings by the local community. These lands were acquired by private developers following the construction of the port, prior to the official start of CPEC. They planned hotels and housing schemes but, now that the hammerhead has been declared a strategic location for surveillance, a naval base is being constructed in its southeast. On the inhabited strip leading to the hammerhead are the old town and the existing new town of Gwadar, where fishing communities displaced by the construction of the port were relocated.

The port is on the east bay, facing away from the Iranian border, where two other controversial aspects of the new masterplan are also situated. The first is the so-called “Oil City”—a new addition to the masterplan—which sits beyond the bounds of the planned city and is projected to include industrial zones and a coal-fired powerplant. The second aspect, which has been the target of a sustained campaign by the fisherfolk, is the construction of the Gwadar East Bay Expressway. This six-lane highway is being built along the bay—much of which has been declared an industrial zone—to connect the port and adjacent free zone to Oil City and the coastal road that leads to Karachi, Pakistan’s biggest city and its main port. This road, which effectively cuts off the fisherfolk’s access to the sea, is a crucial connection, and has led to heavy restrictions on the local fishing community’s use of the east bay. These restrictions are the direct result of the spatial planning of the masterplan and brings to the surface two issues: how worlds are differently orientated, and how, through restricting access to the sea, the very promise of “prosperity” is questioned.

Gwadar Smart Port City Master Plan (2017–2050). Source: Gwadar Development Authority.

Most images of the “soon-to-prosper” Gwadar circulated by the state and real-estate agencies center on the dramatic hammerhead peninsula and the sweeping views from above as it opens up towards the Arabian Sea—a north-south orientation. However, the local fishing community’s world is differently oriented. What are now referred to as the East Bay and West Bay in the masterplan are locally known as Demi Zir and Paddi Zir—front sea and back sea, or, more accurately, behind the back of the sea. This naming speaks to the importance of what is referred to as the “front sea,” or the East Bay, which is where the richest fishing grounds are located and where the lives of the mahigeer (fisherfolk) play out. The West Bay, behind the back of the sea, is where the fisherfolk repair their boats and shelter them from winter storms. As is recognized by journalists and academics alike, the coveted geo-strategic location of the Gwadar port in the East Bay also happens to be a naturally deep harbor, able to accommodate the largest of ships.8 Yet what is less discussed outside of Gwadar is that this particular area is the most fertile and prized breeding ground for tiger shrimp. This area used to be so abundant with valuable shrimp that fisherman could catch hundreds without even trying, but with the port built on their main breeding site, catch has declined severely.

While the natural harbor is deep enough for the large ships and oil tankers that are predicted to flock to Gwadar, their route into the port needed to be carved and dredged out of the seabed. In 2014, routes were cut out and sand thrown back into the sea, shifting the nature of how the sea water interacts with the seabed and forms waves. Local fishermen, well-versed in the ways of the sea, its ebb and flow, the timing and direction of its tides, watched in dismay. They knew what the dredging company either did not bother to find out or had simply ignored: that the direction of the waves depends on many things, including, crucially, the shape of the seabed. Within a week of the dredging, a powerful cyclone hit the Gwadar area and destroyed fifty-two houses in the small fishing village of Sur Bandar on Demi Zir.9 The eastern bay that was previously protected from the highest waters had been exposed to the wrath of the sea. Dredging may not be the only or primary cause of the larger waves, since sea erosion and incursion have been steadily increasing due to climate change, but the destructive potential of the sea had also not been mitigated against by the construction of sea walls.

Land and Sea

Currently, Gwadar’s fisherfolk are in conflict with the state over access to land and sea. That is most visible at Dooriya. “Door” in Balochi means a place that is sheltered from the sea winds, and Dooriya is the main working beach of the fisherfolk on the rich fishing grounds of the East Bay. Sustained protests against the highway, organized by Mahigeer Itehad, a grassroots fisherfolk organization, have led to a few small concessions: the promise of three underpasses to allow access to the sea. These were originally designed to be just six-meters wide, a narrow passage that would only allow access for a few boats, but now the government has agreed to a width of sixty meters. The fisherfolk that are most affected by the road are those who own small boats, going out only a few miles from shore and coming back the same day. This is small-scale artisanal fishing that requires space on the beach for the fish to be shaken out of the nets, a sheltered area close to the beach for fixing the nets, and access for the donkey carts that take the fresh fish to the nearby auction hall to be sold and processed.

The fisherfolk have other demands, too, such as new auction halls to sell fish, scholarships for their children, and job opportunities at the port, as well as the construction of breakwaters to protect their boats from the increasing severity and frequency of storms.10 While it seems that some of these demands may be met, the fisherfolk have nothing in writing. So, they protest every Friday after the Jumma congregational prayers, with the military watching over them and the construction of the expressway. This ongoing conflict at Dooriya is hardly mentioned in the national press. However, the protests are covered by local journalists who are committed to writing about local issues and the struggles around development.

Many of the usual suspects in Pakistan’s neoliberal housing market are present in Gwadar, making money through land grabs, exploiting uncertain land title, and buying land for cheap where possible. But this model was developed by others well before the private sector perfected it; the Pakistani military can take land at will under ordinance and has used such lucrative developments to entrench its power, such as the Defence Housing Authority (DHA).11 This mode of militarized housing development is a hallmark of contemporary Pakistan, and any city worthy of its name will have its DHA zone: the preferred neighborhood for the upper-middle-classes. A recent report counted the myriad commercial entities that allow the army economic access to every aspect of everyday life in the country, from cement to cereals.12 While DHA has not yet arrived in Gwadar, the navy is developing its own private housing scheme: Naval Anchorage Gwadar.

Speculative real estate activity has transferred land from indigenous owners to private development companies and wealthy individuals from other more prosperous parts of Pakistan. Some local people have also made money by selling off their ancestral lands, while others feel they have lost out on huge sums as they were not able to prove ownership of their lands and were thus resigned to watch as “their” land was sold to people in Karachi, Lahore, or Islamabad. Non-existent plots have changed hands for huge sums while the people of Gwadar have looked on amused. The process of land ownership in Pakistan is never a straightforward business and includes multiple brokers and stakeholders, all of whom are looking to make profit. Such stories seem to provide some solace to a local community that feels that the exploitation of Baloch lands is going unchecked. Whether under military or private control, the fencing off of land has changed the feel of the place; where it was once open and used for grazing, now paths have been cordoned off and common access has been removed.

Silence, Security, and Speculation

The narrative around Gwadar is also fueled through different forms of media controlled or partially managed by the Pakistani state. Just around a year and a half ago, protests by the fisherfolk were gaining momentum and the insurgency was spreading more widely in Balochistan, which resulted in the disappearance of activists, students, intellectuals, and ordinary citizens whom the state considered to be supporting the insurgency. At that time, a number of vloggers emerged across the country, including in Gwadar. These young people are being supported and given a platform by the state in order to provide controlled messaging around major issues including development. The case of Eva Zu Beck, the Polish travel blogger who was welcomed by the Pakistani government to help spread the message of tourism is well documented.13

In Gwadar, a young woman vlogger emerged, Anita Jalil Baloch, who has been praised for providing a progressive example of women’s empowerment. Her videos of daily life in Gwadar have contested some of the more hyperbolic nationalist statements around the transformation of Gwadar into a new Dubai. One of her first posts was about the lack of electricity in the city, but after receiving negative feedback, her videos have become more upbeat, focusing on cultural and educational topics in and around Gwadar.14 Vlogging has created space for independent youth in Gwadar to relate the cultural lives and everyday practices of local communities, offering a deeper insight into the existing cultural and heritage landscape. In some sense, this lure to present Gwadar as a valuable location, now due to its culture, continues to fuel the larger imaginary of Gwadar as a hub of prosperity. However, in the political context of Pakistan, and especially of Balochistan, some things are better left unsaid, and the local community is well-versed in what can be spoken of and where silence should be maintained.

Travelling to Gwadar in early 2015, there was a palpable sense of feverish speculation around Chinese investment. The port itself was inaugurated in 2007, but it was not considered to be formally operational until 2016, although even then this was a misnomer; the port may have been operational, but it certainly was not operating. An amusing story circulating around Gwadar at the time was that a ship bound for Port Qasim in Karachi was commandeered by the Pakistani authorities in order to form a suitable backdrop for Gwadar port’s glitzy inauguration ceremony. Yet, despite the healthy cynicism, there was also an air of expectation; something was at least happening in Gwadar. Upon interviewing the fishermen about the port and how it had affected their lives, their answers were telling:

What is the port to me? The port is a treasure for us—I agree with this. If it’s a treasure for Pakistan, we could also try to imagine this. To give us employment there, we would need education. Before laying the foundations for the port, they should have opened an educational institution for us, a training center. They could do so even now …15

Now, five years later, nothing much seems to have changed; the promised construction of skyscrapers and all the amenities of modern neoliberal development have not materialized. Speculative development has remained speculative; still only visible in the hyperreal images and videos produced by companies somewhere in the Gulf or in China. Yet at the same time, almost everything has changed. There used to be a feeling of promise, of anticipation mixed with trepidation. People were expectant about the changes coming their way, hopeful that at least some of the promises made years ago might be fulfilled. They imagined a new future, if not for themselves, then for their children. This was especially true for the mahigeer whose livelihoods had already been affected by the construction of the port and who wished for their children to have a different life. However, the sluggish temporality of infrastructural development and the alienating ways in which it continues to materialize have not only crushed local dreams of prosperous futures, but also, in effect, have performed the slow erasure of the existing landscape. On a more recent visit, although still considerably low, the hopes of local people remain as they continue to resist the tendency of reducing their imagined futures to the present on-ground situation.

While those changes that were used to seduce have not materialized, the landscape has changed indelibly. The imaginaries of infrastructural development in Gwadar have materialized in multiple and variant ways, from the cordoning off of indigenous people from their own lands and managing access to their seas to the violent disqualification of their desires and aspirations to partake in the development of Gwadar. Rather than operating as the promised hub of free flows and movement, Gwadar has become an increasingly controlled and restricted landscape for local people while multiple actors make claims to these indigenous lands. What were once beautiful picnicking spots on the hammerhead in Gwadar overlooking the Arabian Sea are now part of a naval base. It is difficult to overstate the effects of the loss of such public areas of natural beauty in places like Gwadar that have long been neglected by both the provincial and federal governments. There is very little to do in Gwadar. Areas of natural beauty, empty, fenced off, and guarded by a hapless soldier with a few lonely benches and a hastily constructed folly are common in Pakistan. The military stakes its claim on all natural resources, not just the gas, mineral, and gold deposits that come out of the ground, but also the breathtaking panoramas and secluded spots that are apparently only accessible for the privileged classes with military connections.

Even in places where speculative development has happened, like the Chinese-built Business Center, which is supposed to house visiting Chinese delegations and other dignitaries, there is an eerie silence. For all the fanfare and promise of infrastructural development, plans seem to be forever deferred and delayed. Beyond the construction of the port, most of what has materialized are roads: main roads, side roads, and roads marking out housing societies that cut through the dusty landscape. They often end abruptly or seem to lead nowhere. In some instances, there are fenced off areas with billboards whose renderings of palm-tree-lined boulevards and glass buildings have faded in the heat of the sun. In this sense, Gwadar presents a space of disjuncture between the promise of a prospering smart port city and the reality of displacement, half-built housing schemes, restricted access, and cordoned off areas. Prior to intervention, Gwadar was just going about its everyday life. But now, it is a landscape forced to await the fulfillment of someone else’s dream.

George Delisle, “Mud Volcanoes of Pakistan: An Overview,” in Mud Volcanoes, Geodynamics and Seismicity, ed. Giovanni Martinelli and Behrouz Panahi (Springer, 2005): 159–69.

Due to this, it proved to be an important base for the British colonialists who were stationed in Gwadar, as well as the Indo-European telegraph line in 1867-1870.

Voice of Gwadar, “Gwadar Is the Jewel in Crown of CPEC: The Key Pillar of BRI,” Voice of Gwadar, September 12, 2019, ➝.

For a full list of projects, see “CPEC Vision & Mission,” China–Pakistan Economic Corridor, ➝.

This is not the place to discuss these contracts at length, but for more information, see The China Africa Project, ➝.

The independence movement gains popular support through the discriminatory practices of the Pakistani government and the conduct of the army, for example, the revenue from the province’s natural gas and mineral resources have not benefited the local population, and the Pakistani army has been accused of disappearing thousands of Baloch Nazish, “Balochistan’s Missing Persons.”

CPEC’s avoidance of certain areas due to “security concerns” match almost perfectly areas that have long been neglected by the Pakistani state. The rerouting of CPEC through Pakistan’s most prosperous and populous province of Punjab, which also happens to be the current stronghold of the ruling party, seems to be no coincidence.

Filippo Boni, “Civil-Military Relations in Pakistan: A Case Study of Sino-Pakistani Relations and the Port of Gwadar,” Commonwealth & Comparative Politics 54, no.4 (2016): 498–517; Rorry Daniels, “Strategic Competition in South Asia: Gwadar, Chabahar, and the Risks of Infrastructure Development,” American Foreign Policy Interests 35, no. 2 (2013): 93–100; Hasan Malik, “Strategic Importance of Gwadar Port,” Journal of Political Studies 19, no. 2 (2012): 57–69.

Behram Baloch, “Storm Wreaks Havoc in Gwadar,” Dawn, June 18, 2014, ➝.

Some new jetties and breakwaters have now been built, but their location and direction have been questioned by the fisherfolk who claim not to have been properly consulted. Mariyam Suleman, “Will China’s Plans for Gwadar Destroy Fishermen’s Livelihood?,” The Diplomat, April 3, 2019, ➝.

See Ayesha Siddiqa, Military Inc.: Inside Pakistan’s Military Economy, 2nd edition (Pluto Press, 2016).

Amir Wasim, “50 Commercial Entities Being Run by Armed Forces,” Dawn, July 21, 2016, ➝.

Behram Baloch and Muhammad Akbar Notezai, “Situationer: Meet Gwadar’s First Female Vlogger,” Dawn, September 21, 2018, ➝.

Mahigeer Itehad Gwadar, February 2015.

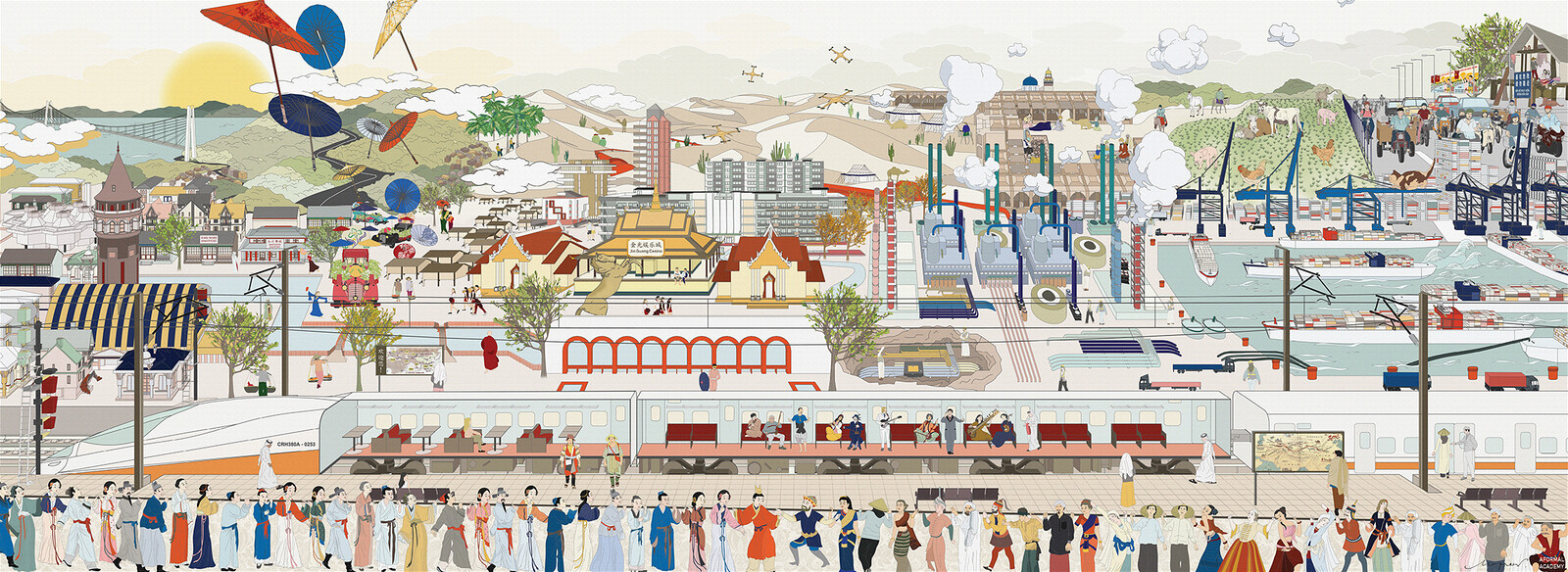

New Silk Roads is a project by e-flux Architecture in collaboration with the Critical Media Lab at the Basel Academy of Art and Design FHNW and Noema Magazine (2024), and Aformal Academy with the support of Design Trust and Digital Earth (2020).