The Perpetrator

On November 29, 2017, I was in Rotterdam, having a meeting in a café, when I received a text message from my mother. I’d been nervous all day because I knew the court would be announcing its ruling. Would he get a life sentence, or one of those senseless punishments that war criminals often receive and which leave the surviving victims utterly disillusioned? The text message said: “He’s poisoned himself.” Nothing more, nothing less. Although my mother and I hadn’t discussed the trial, we knew we had both been following it closely. I’d seen him years before, after he’d just turned himself in to the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia in The Hague. I attended one of the hearings where he was on trial with his fellow war criminals.1 I sat in the public gallery, and to my horror, I wasn’t surrounded by other victims, but by the perpetrators’ relatives. I was there because I wanted to know what someone looks like who is capable of purging a land of a group of people and their cultural heritage due to their religious identity. Above all, I wanted to know what kind of people these criminals were. Seeing them in person was a disappointment. They talked, smiled, and signaled to their lawyers. They didn’t look unhappy or remorseful.

Slobodan Praljak drinks a bottle of poison in the courtroom in The Hague, November 29, 2017. Source: International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia.

The text message startled me. During the meeting, I kept checking news sites on my phone to see what had happened. The court had sentenced Slobodan Praljak to twenty years for four counts of grave breaches of the Geneva Conventions (willful killing; unlawful deportation, transfer and confinement of a civilian; inhuman treatment; extensive destruction of property and appropriation of property), six counts of violations of the laws or customs of war (cruel treatment; unlawful labor; destruction or willful damage done to institutions dedicated to religion or education; plunder of public or private property; unlawful attack on civilians; unlawful infliction of terror on civilians), and five counts of crimes against humanity (persecutions on political, racial and religious grounds; murder; deportation; imprisonment; inhumane acts).2 Praljak also ordered the destruction of Stari Most (Old Bridge) in Mostar, footage of which was televised on news channels around the world. After sentencing, Praljak stood and said: “Judges, Slobodan Praljak is not a war criminal. With disdain, I reject your verdict,” and then drank a bottle of poison. Shortly after, he lost consciousness, and the curtain in front of the public gallery was hurriedly drawn. Despite Praljak’s widely reported death, I tried to convince myself that I shouldn’t believe it yet. I didn’t want to believe it. I was angry because Praljak had taken matters into his own hands. He would not serve his sentence, and the drama of his death distracted from his crimes.

The destruction of the Old Bridge in Mostar on November 9, 1993. Source: Evan Genest, Two Dishes But To One Table, 2006.

The Victim

On November 9, 1993, the Stari Most—Mostar’s oldest inhabitant—was destroyed. The bridge and the city were always one. Mostar is named after the bridge keepers, mostari, who kept guard from their fortified towers, checking those crossing the Stari Most over the Neretva river. In addition to symbolizing the city and joining its two parts, the bridge also represented tolerance and unity. The city was the bridge, and the bridge was the city. It was a meeting place. For generations, it was the place young couples would meet on their first date, and was where Mostar held its famous annual diving competition. The attack on the bridge was an attack on the concept of multi-ethnicity. With the bridge gone, Mostar would cease to exist, and along with it the city’s soul. And that’s exactly what happened. When Praljak ordered the bridge’s destruction, Mostar seemed to take its last breath of air. The city was a mere mortal; Mostar was dead.

Before it collapsed, the bridge was hit by sixty shells in twenty-four hours. Besides the bridge, other structures that furnished public life were also destroyed: libraries, museums, universities, mosques, squares. The destruction of these places was part of a broader war strategy in which Praljak used the demolition of public and cultural buildings as a means to erase a specific culture and identity. Milan Kundera’s description of genocidal strategies in The Book of Laughter and Forgetting are directly applicable to those Praljak and his fellow war criminals employed:

The first step in liquidating a people is to erase its memory. Destroy its books, its culture, its history. Then you have somebody write new books, manufacture a new culture, invent a new history. Before long, the nation will begin to forget what it is and what it was.3

The Motive

I have often wondered what kind of person Slobodan Praljak, this architect of destruction, was. Did he have a military past? Did he spend his entire life in a bubble of nationalism and hatred? Did he act out of ignorance, or even stupidity? The opposite turns out to be the case. Before graduating from the film and television academy, Praljak had obtained three university degrees in electrical engineering, philosophy, and sociology. In the 1970s and 1980s, he was director of several theatres, including in Mostar. In her article “The Cultured Destroyers of Culture,” Gordana Knezević describes how “the man of culture became a general”:

Some of the most notorious acts of destruction of cultural heritage—aimed at removing all traces of the Muslim population from areas of Bosnia that the Croats considered to be “theirs”—were masterminded or carried out by men who before the war had built a reputation as “promoters of culture.”4

Praljak, it seems, was acutely aware of the consequences of destroying cultural heritage and public architecture. He knew very well that architecture could become part of his war strategy precisely because he had gained so much knowledge and experience in the Croatian and Bosnian cultural milieu. His experiences taught him its symbolic value and significance. By obliterating important public places that made the city vibrant and tolerant, spaces where it didn’t matter what your religion or ethnicity was—because one was always a Mostarac or a Mostarka—Praljak knew that he would also erase Mostar’s identity.

In a short film from 2003, TV presenter Marinko Učur of the Bosnian Alternativna Televizija Banja Luka interviewed Praljak about the destruction of the Old Bridge. Praljak denied the fact that the “Croats” destroyed it, and gave his explanation for the events in Mostar:

We [by which he means Croats or Bosnian Croats] are stronger. It is our city. We are the dominant group there. And what is more, we work better. That’s right; we work better. We deliver better quality work. We are more powerful… The bridge is a symbol of nothing. The bridge is beautiful; let’s be honest. The construction is beautiful, just like other beautiful things. But this idea that it’s a symbol of something, this is little European [expletive] coming here and telling us that symbols need to be built. No! …The bridge symbolizes nothing. Not brotherhood or humanity.

Praljak knew Mostar well and fully understood that the Old Bridge and its significance were integral to the identity of the city’s inhabitants. The bridge was always there, not only as a structure in the city, but also as a cherished icon depicted in the many tattoos, paintings, sculptures, embroideries and key rings of Mostarce and Mostarke. And among the residents, whether Bosniak or Croatian, the bridge’s significance transcended religion. The book Mostar ’92 Urbicid cites Džemal Čelić’s explanation for the destruction of Mostar’s bridges:

Studying the old bridges, we shall experience and understand the whole history of our country where bridges appear as road signs of positive movements of culture and civilization in any span of the times passed. Therefore we cannot accept their destruction in the latest war as a result of strategic necessity, but as a violence against the identity of our peoples.5

The Target

Because the Old Bridge was built during Ottoman rule (and was therefore Turkish/Islamic), Praljak associated it with those people who had an Islamic background, as if the bridge belonged to them. However, it belonged just as much those of Croatian descent. The destruction of the Old Bridge and the killing and purging of Muslims destroyed any possible kinship between the Croats and Bosnians. The two religious groups were physically separated from one another and any breath of connection, multiculturalism, and tolerance eradicated.

After the war, Mostar was further segregated, and architecture and public areas were used to appropriate space in the city for singular ethnic identities. Many religious symbols and monuments, especially on the Croatian western side of the town, were added to public space; streets were renamed often with nationalistic significance; and ethnically and politically-colored institutions were given prominent places in the city. The two groups now live separately, each with their own schools, history books, hospitals, postal services, football clubs, and so on.

Stari Most was rebuilt in 2004. It looks the same as before the destruction, only a little cleaner and paler. The Old Bridge was rebuilt in the way monuments used to be built. But to build it this way only reinforces Praljak’s and his fellow war criminals’ aims. After all, they destroyed not only the site but also the residents’ experience of the bridge. The Old Bridge was a place from where you could look past differences and where common experiences could be shared. Praljak destroyed this place, just as all the city’s places have been destroyed. Mostar will never be the same again. The bridge now symbolizes the separation of the two parts of the city and contains an abundance of fragmented, imaginary, self-proclaimed, and self-imposed memories. The goal seems to have been achieved.

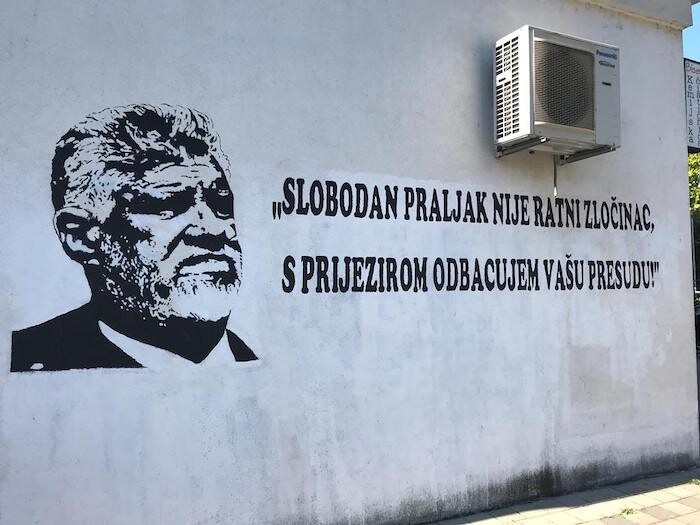

Graffiti drawing of Praljak in Čapljina, Bosnia and Herzegovina. Text reads: “Slobodan Praljak is not a war criminal. With disdain, I reject your verdict.” Photo by Arna Mačkić.

Counter-Attack

I was born in Čapljina, just like Slobodan Praljak, on the Bosnian-Croat border. During the war, Praljak and his fellow war criminals also took over this city, expelling the non-Croatian population and setting up concentration camps for the Bosnians. Praljak was in charge of Camp Dretelj, where my father was imprisoned. When I was in Čapljina last year, I saw graffiti on an apartment building near my old house that portrayed Praljak’s face, along with his last words before drinking poison. Many in Čapljina still consider him a hero. I feel increasingly uncomfortable in Čapljina’s public spaces.

My father is from Mostar. After the war, I spent a lot of time there because Bosnian Croats still occupied our house in Čapljina. In the summers we spent in Mostar, I got to know the city better, and the fierce divisions in the city became apparent. My brother and sister and I often stayed at my great-uncle and great-aunt’s who lived in the city’s western, Croatian area, but my father was afraid to visit that side of town. I learned that some parts of the city were out of bounds since my surname would reveal my Islamic background. But as I got older, I began exploring both parts of the city because I refused to participate in the politics of division.

Architects and architecture critics are eager to discuss, criticize, celebrate, or loathe new buildings. Yet when buildings, monuments or even entire neighborhoods and cities suffer deliberate destruction, they are less vocal. Indeed, the architect’s responsibilities should also include understanding why and how destruction takes place and the possible responses. What can an architect add to a city like Mostar, where many monuments, cultural buildings and institutions, and public meeting places have been destroyed, and where new monuments and buildings are ethnically divided?

Active Monuments

In a city like Mostar, where one-sided views of history endure, it is imperative to create places that bring people with different historical perspectives together and in which different stories have a place. Such places urge people to rethink their viewpoint; they allow for a shared experience and play a part in the daily life of the city’s communities. Places such as these can be thought of as “active monuments.”

The Old Bridge is a point of inspiration for thinking what an active monument in Mostar could look like. One of Mostar’s most important historical traditions is diving from the Old Bridge, which first took place in 1567. It used to be a ritual in which young men would dive from the bridge to prove their masculinity and impress young women, but later became a tradition that was proved belonging to the city and was passed down from one generation of Mostar men to the next regardless of religious belief. The diving competition still takes place annually, with renowned high divers (both men and women and from different religious backgrounds) coming from around the world to take the plunge. For Mostar, it is a tradition that stems from the city’s origin and being. Even after the war, with the Old Bridge gone and before a temporary cable bridge appeared, a platform was created from which people could dive.

Since the Old Bridge is now part of Mostar’s eastern half, which is mostly home to Bosnians, Croatians from the city’s western side hardly visit the bridge. Although the Old Bridge’s unifying significance has ceased, its age-old diving tradition could play a role in restoring the unity between different religious groups. To investigate this, I designed a speculative diving school on the border of the western and eastern part of the city where residents can learn to plunge into the water from a great height. It is an urban activity for all residents of the city, regardless of nationality, religion, gender or age.

The proposed monument would be situated opposite a high school where students with a Croatian, Islamic, and international background study (although classes are still segregated). The monument is freely accessible and has no windows, doors, or roof. Its access is a vast inverted trapezoidal staircase that ascends to create two protruding points on either side. The fifty-centimeter steps encourage learning higher diving in half-meter increments. The steps also function as a tribune where people can sit and gather. Swimming and diving teach Mostar’s inhabitants to keep their heads above water, literally and figuratively. The three-second plunge into the water gives a feeling of weightlessness and freedom, disconnecting you from everything around, including Mostar’s fraught public space.

In Practice

I never intended to realize this design. Rather, the idea was to propose new, collective, active monuments that would encourage discussion among Mostar’s residents and authorities. What kind of public space is desirable? Do we want public space that connects different—now estranged—groups? Are we able to meet the other through shared experiences? Is my proposal a good example of this?

My book Mortal Cities & Forgotten Monuments was translated into Bosnian the week after Praljak drank poison to kill himself. Mostar was tense. Praljak’s supporters were honoring him with candles and flowers and shouting nationalist slogans in the square in front of the cultural center where the book launch would take place. The situation was uncomfortable. Not only because of my family’s suffering through Praljak’s crimes, but also because I was promoting a book about connecting architecture and humanity in a context where unity was hard to find. For the sake of caution, security was present during the book presentation. The event had a somber atmosphere, with just a handful of people in the audience, most of whom were family members. Those gathered asked hardly any questions, and there were no comments about my proposal. Anxious and despondent about what was going on outside, everyone seemed numb and afraid to talk about connecting to others through public space.

However, my impressions changed the following day. Aida Calendar, director of the NGO Akcija Sarajevo, organized a diving workshop for children at a nearby bathhouse. Local hero Lorens Listo, multiple winner of Mostar’s annual diving competition, gave lessons to a group of children from both sides of the city. Naturally, the children were thrilled. Listo taught them diving techniques and also about the tradition’s significance for the city. Despite their different perspectives and backgrounds, the shared, playful experience of learning to dive and discussing history inspired togetherness. The active monument was not the physical structure I designed, but the diving workshops. They give a new generation a face.

Nevertheless, it isn’t only Mostar that demands a new space to commemorate the Bosnian War of the 1990s. “Srebrenica is Dutch History” is a campaign that draws attention to the genocide that took place in Srebrenica twenty-five years ago, where more than 8,000 Bosniak men and boys were murdered while they were supposed to be protected by Dutchbat, a Dutch battalion under the command of the UN, by nationalist Bosnian Serb soldiers and a paramilitary unit from Serbia. The failure to protect these civilians marks a dark chapter in Dutch history and will forever connect Bosnia-Herzegovina and the Netherlands.

However, this shared history lacks the attention it deserves. The genocide is hardly covered in Dutch history education, there is still no national monument to commemorate this event, and the government does not provide structural funding for the annual Srebrenica commemoration in The Hague. To anchor long-term awareness and reflection on this history in various public domains of Dutch society, we developed an online photo series, a short campaign film, an educational website with articles and documentaries, and a temporary monument that stood for three weeks starting on July 11, 2020, the twenty-fifth anniversary of the Srebrenica massacre.

The temporary monument comprised twenty-five large portraits and the stories of twenty-five-year-old Bosnian-Dutch men and women on Het Plein, a public square adjacent to the Dutch Parliament. The twenty-five young people from different religious backgrounds formed a circle and shared their stories of the war they did not experience. In so doing, they not only kept alive the memory of the 8,372 murdered Muslim men and boys, but formed a protective circle around their next of kin, other survivors from throughout Bosnia-Herzegovina, Dutchbat soldiers, and beyond.

“Jadranko Prlić, Bruno Stojić, Slobodan Praljak, Milivoj Petković, Valentin Ćorić and Berislav Pušić were all found guilty of crimes against humanity and other crimes against Bosniaks while they were senior political and military officials of the Herzeg-Bosnia statelet during wartime.” Erna Mačkić, “Bosnian Croat Disrupts Hague Verdict by ‘Taking Poison,’” Balkan Transitional Justice, November 29, 2017, ➝.

“Case Information Sheet: The Prosecutor v. Jadranko Prlić, Bruno Stojić, Slobodan Praljak, Milivoj Petković, Valentin Ćorić & Berislav Pušić,” International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia, November 29, 2017, ➝.

Milan Kundera, The Book of Laughter and Forgetting (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1980), 159.

Gordana Knezević, “The Cultured Destroyers of Culture,” RadioFreeEurope RadioLiberty, November 28, 2017, ➝.

Krešimir Šego et al., Mostar ’92 Urbicid (Mostar: Hrvatsko vijeće općine, 1992), 27.

Monument is a collaboration between e-flux Architecture and Het Nieuwe Instituut.