According to the worldview of my ancestors, wai (water) is everything. To us, the Indigenous peoples of Aotearoa New Zealand, known collectively as Māori, we live daily with this knowledge through our language, stories, songs, laws, and histories. For example, in greeting someone new, we ask “Ko wai koe?” which queries “Who are you?” but more literally translates as “Who are your waters?” The answer will depend on which tribal nation that person belongs to. For me, through my paternal grandfather’s genealogy (Raukawa), one of my waters is the Waikato river. All tribal nations here have these geographical identity markers linked to water (and also to mountains). The link between land, water, and humans is a common linguistic feature. For instance, iwi means both tribal nation and human bone; hapū means both subtribal political group and to be pregnant; whānau means both extended family and to give birth; whenua means land and afterbirth. Wai means water, but also memory and “who.” These relational understandings of water influence a Māori way of knowing the world.

The Māori legal system is predominantly values, not rules, based.1 It encapsulates a certain way of life that depends on the relationships between all things, including between people and gods, different groups of people, and people and everything in the surrounding world. Key legal values include the importance of genealogy and intergenerational family relationships that link humans to sky, earth, mountains, and rivers; the respect of the life force of the lands and waters; and societal balance and hospitality.2 One key concept, utu (reciprocity), plays a regulatory role because everything given or taken requires a return of some kind in order to ensure similar acts of continued generosity and to maintain harmony and balance. Kaitiakitangai (guardianship) is another example of a term that “more than managing relations between environmental resources and humans… also involves managing relationships between people in the past, present and future.”3

But, when the British arrived to New Zealand in the late 1700s and asserted sovereignty over the country in 1840, the imposed colonial law and order permitted little national recognition for, and application of, the Māori legal system. In contrast, the inherited British legal system is predominately rules driven, with no underlying worldview establishing people and lands as familial relations.4 This colonial system of law draws lines and creates different rules for how river and lake banks and beds, navigable flowing waters, and rough unnavigable rivers can be owned and managed.5 Usual common law rules assume, for example, that beds of water can be owned, but not the water above it, and that an adjoining land owner to a river owns the riverbed to the river’s middle flow.6 Such conflict between the two legal systems remains highly contentious, yet significant progress towards co-existence and recognition have recently been made.

A word on comparison

The relationship between the Māori, the New Zealand Government, and society at large is somewhat different to that of other Indigenous peoples, such as the American Indians. This is partly because those who identify as being of Māori descent constitute about fifteen percent of New Zealand’s nearly five-million-person total population. Contemporary law simply defines Māori as “a person of the Māori race of New Zealand; and includes a descendant of any such person.”7 This population make-up, and simple legal definition, is clearly different than the United States where, for example, American Indian and Alaskan Native peoples account for under two percent of the total country population.8 In New Zealand, Māori are visibly present throughout the country, integrated into all parts of society, and share a long history of intermarriage with Europeans and others.

The inclusive descent definition for who is Māori works because few legislative rights hinge on being classified as Māori. The British colonizers in New Zealand did not do as they did in North America where they drew arbitrary survey lines on the land in the pursuit of creating reservations in which its Indigenous peoples would be forced to reside. Instead, in New Zealand, the general colonial starting point was that all land was Māori land, and such land was available for the British to take (steal) for their own purposes. The flagship moment in establishing these early relations was the signing of a single bilingual treaty, the Treaty of Waitangi. This is the document that the British Crown and many Māori chiefs signed in 1840 stating that, according to the English version, Māori ceded sovereignty to the British Crown but retained full exclusive and undisturbed possession of their lands, estates, forests, fisheries, and other properties.9 The Māori language version has some significant translational differences from the English version. According to the Māori version, Māori retained their sovereignty over their lands and treasures but otherwise gave governance rights to the British Crown to manage the influx of Europeans.

Less than twenty years after the treaty was signed, the New Zealand government had “acquired” about sixty percent of New Zealand’s land mass (contrary to the Treaty’s guarantees). Law quickly enabled the confiscation and acquisition of most of the remaining lands.10 Less than six percent of the country is now held in Māori freehold land titles, and much of this is in remote areas uninhabited by Māori. This colonial experience is obviously different from that of the American Indians, which involved reserves and the consequent discourse of sovereign nations, identity, and reserved rights.11

Also unlike in the United States, New Zealand is a constitutional monarchy with a parliamentary system of government. It has a unicameral legislature where Parliament is supreme and has no formal limits to its law-making power.12 Furthermore, Māori, as parties to the Treaty of Waitangi, have no general constitutional rights to rely on in the courts. This is in part because New Zealand does not have a formal constitution that recognizes Māori rights as the first peoples of the country and their rights as distinct from those of other citizen’s.13 However, in New Zealand, some legislation does now reference the Treaty and provides certain legislative rights of consideration for Māori, including the main statute that regulates rights to water: the Resource Management Act 1991.

The Resource Management Act 1991

Passed in 1991, the Resource Management Act is silent on who owns water but vests day-to-day control in local governments. Accordingly, district and regional councils prepare plans that contain rules for the sustainable management of the environment and stipulate when and where proposed activities should require “resource consents” that permit use. Specifically, regional councils assert rules and guidelines for the take, use, damming, and diversion of freshwater; they control the use of land within their regions for the purpose maintaining and enhancing the quality and quantity of water in water bodies; and set maximum and minimum water levels and flows. Local governments are also responsible for the infrastructure required to build and maintain domestic water supply, such as pipes and wastewater systems, and stormwater management area controls.

The Resource Management Act marked a new era in environmental management because it provided some recognition of the Māori legal system. It lists several matters of national importance, including a direction to all decision-makers in formulating plan rules and issuing resource consents to recognize the Māori relationship with water. Other stated matters of national importance include preserving the natural character of lakes and rivers from inappropriate development, protecting outstanding natural landscapes and significant habitats of indigenous fauna, and maintaining public access to lakes and rivers.14 These decision-makers must also have particular regard to kaitiakitanga, which is defined in section 2 of the Act to mean “the exercise of guardianship by the tangata whenua (Māori) of an area in accordance with tikanga Māori (Māori law) in relation to natural and physical resources; and includes the ethic of stewardship,”15 and “take into account the principles of the Treaty of Waitangi (Te Tiriti o Waitangi).”16

Despite the seeming inclusivity of the law, it has done little to significantly protect Māori interests. Since its enactment, when Māori object to the issuing of resource consents to take, discharge, or dam water, they almost always lose in the courts.17 Rather than resource consents, what are called Treaty claim settlement reconciliation statutes have been the catalysts for more effective recognition and provision of Māori relationships with water and the environment.

Treaty of Waitangi claim settlement statutes

Since the mid-1980s, New Zealand has seriously committed to reconciling with Māori. More than thirty “settlement statutes” have since been enacted throughout the country between Māori federations and the national government that provide financial, commercial, and cultural redress for government actions or inactions that breached the principles of the Treaty of Waitangi.18 Many of these settlement statutes recognize the specific importance of water to Māori identity, health, and wellbeing. Some have been particularly revolutionary in developing cultural redress options which give Māori joint environmental management responsibilities with regional governments for lakes and rivers. But none have gone far enough in disrupting the inherently colonial notion of either “no one owns water” or “water is the assumed property of the Government.”

All of the claim settlement statutes begin with extensive government apologies to Māori for historical actions that breached the Treaty of Waitangi. These apologies include acknowledgements of the importance of land and water to Māori and are often recorded in Māori and English languages. The acknowledgements are sometimes recorded using Māori cultural features such as proverbs, songs, poetry, and creation stories for the lands and waters of Aotearoa New Zealand. While New Zealand has yet to recognize Māori ownership of water, it is becoming mainstay to recognize Māori ownership of lake beds, co-governance of lakes and rivers, and the recognition that significant water bodies are related ancestors.19

Co-governance in practice

Lake Taupō (1992)

New Zealand’s largest lake by surface area, Lake Taupō is the treasured lake of Ngāti Tuwharetoa. In 1992, the national government vested the ownership of the lakebed in the Tūwharetoa Māori Trust Board. This meant that the Board attained the right to license and charge fees of commercial users of the lake and those wanting to erect new jetties or structures. The rights of non-commercial users remained unchanged, including free public access. In 2018, the Tūwharetoa Māori Trust Board entered into a co-management arrangement with the Waikato Regional Council to share responsibilities for the Taupō waters, including making joint decisions on whether to issue resource consents, including for water withdrawal and/or discharge. This lake is surrounded by pastoral farming, forestry, and residential homes, and is an internationally renowned trout fishery destination. The lake’s water quality is of concern, with increasing amounts of nitrogen leaching into it from the surrounding lands. This co-management announcement was welcomed by the Trust Board as a milestone and as a further step toward realizing Māori self-determination over generational treasures. The Council likewise applauded the co-management arrangement: “We have seen the value of the inter-generational vision that Ngāti Tūwharetoa brings to the council’s decision making including their extensive experience and knowledge of freshwater resources, which are some of our region’s most significant [treasures].”20

Te Arawa Lakes (2006)

In 2006, the first settlement statute that focused entirely on water, the Te Arawa Lakes Settlement Act, was enacted. This Act recognizes the significant relationship between the North Island federation, Te Arawa, and fourteen lakes that lie within the Te Arawa traditional geographical boundaries. These lakes are situated in and around the Rotorua city that is a major international tourist destination. The Act recognizes that the lakes are of spiritual, cultural, economic, and traditional importance to Te Arawa. Past government actions that threatened these relationships are acknowledged, including the impact of introducing exotic fish species into the lakes that then depleted native species, as well as the practice of prosecuting Te Awara members for fishing without licenses. Part of the government apology as recorded in English reads:

The Crown profoundly regrets that past Crown actions in relation to the lakes have had a negative impact on Te Arawa’s [sovereignty] over the lakes and their use of lake resources, and have caused significant grievance within Te Arawa. Accordingly, with this apology, the Crown seeks to atone for these wrongs and begin the process of healing. The Crown looks forward to building a relationship of mutual trust and co-operation with Te Arawa in respect of the lakes.21

Waikato River (2010)

In 2010, New Zealand enacted significant legislation that implemented a cooperative management regime for the country’s longest river, one of my family’s waters, the Waikato River. The Waikato-Tainui Raupatu Claims (Waikato River) Settlement Act 2010 and the Ngati Tuwharetoa, Raukawa, and Te Arawa River Iwi Waikato River Act 2010 are premised on a vision that seeks to restore the health and wellbeing of the Waikato River through providing for cooperative management of the River with those multiple tribal federations that link to it genealogically.22 This vision is embedded in the understanding that the Waikato River is an ancestor. For example, the Waikato River Settlement Act reads:

The Waikato River is our tupuna (ancestor) which has mana (spiritual authority and power) and in turn represents the mana and mauri (life force) of Waikato-Tainui…. Our relationship with the Waikato River, and our respect for it, gives rise to our responsibilities to protect te mana o te Awa and to exercise our mana whakahaere in accordance with long established tikanga to ensure the wellbeing of the river. Our relationship with the river and our respect for it lies at the heart of our spiritual and physical wellbeing, and our tribal identity and culture.23

Waipa River (2012)

The Waipa River, a significant contributor to the Waikato River, lies at the heart of spiritual and physical wellbeing for the tribal federation of Maniapoto. The Nga Wai o Maniapoto (Waipa River) Act 2012 recognizes:

Waipa she is the life blood of the people. Waipa she is the life blood of the land, verily she is! Indeed she is the unfailing spring of the earth! She is the water that anoints the thymos of man to bind to the tribe the waters of life that issues forth from the lineage of the atua [god]. She is the water that blesses the umbilical cord to ensure the health of the descendants of Maniapoto. ‘Tis the water that permanently renders the knot of the navel cord secure and fast.24

This Act provides a long list of guiding principles to enable the tribal federation’s vision for the Waipa River. Section 4(13) states: “A guiding principle is kaitiakitanga (guardianship), which is integral to the mana (authority) of Maniapoto.” This guiding principle requires, for example, “recognition and respect for the kawa (rules), tikanga (law), and kaitiakitanga of the marae (traditional home), whānau (family), hapū (sub-federation), and iwi (federation) of the Waipa River.”

Whanganui River (2017)

In 2017, New Zealand gave legal status to the country’s third-longest river and all its tributaries, streams, lakes, and wetlands. Te Awa Tupua (the face of the Whanganui River) became a legal entity with “all the rights, powers, duties and liabilities of a legal person.”25 Māori law is explicitly acknowledged in the Te Awa Tupua (Whanganui River Claims Settlement) Act 2017:

The Crown acknowledges that to Whanganui Iwi the enduring concept of Te Awa Tupua—the inseparability of the people and the River—underpins the responsibilities of the [tribes] of Whanganui in relation to the care, protection, management, and use of the Whanganui River in accordance with the … [law] maintained by the descendants of Ruatipua, Paerangi, and Haunui-a-Paparangi.26

A formal Te Pou Tupua (guardian) has been created to “provide the human face of Te Awa Tupua.”27 Two people fulfill this guardian role: one appointed by the Crown, the other by the Whanganui iwi. The primary functions of the guardian is to promote and protect the health and wellbeing of Te Awa Tupua and speak on its behalf. The guardians work with strategy groups to make recommendations for improving the wellbeing of the river. However, the Resource Management Act continues to vest power with the local authorities to make final decisions to permit or prohibit various activities concerning the river (including the taking of water for domestic or commercial purposes). The difference is that this local decision-making must now be made in a consistent manner with the Māori understanding of this river. One ongoing controversy is the existence of the Tongariro Power Scheme (a 360 MW hydroelectric scheme) that takes water from the head of the Whanganui River. Māori argue the river would be in better shape if the power station was not taking its headwaters.28 It is yet unknown how the implementation of the 2017 Act might affect the station’s operations in the future.

Justice

Despite the government denial of Māori ownership of flowing water, the governance of these lakes and rivers is being rebuilt to create new respectful relationships between the national and local governments and the specific tribal federations. These recent settlements are still predicated on the continuing colonial assumption that flowing water cannot be owned. In particular, the legal personhood approach has been deployed effectively to neutralize the contested ownership issue, the solution being that no one owns the water because it owns itself; it is its own person.

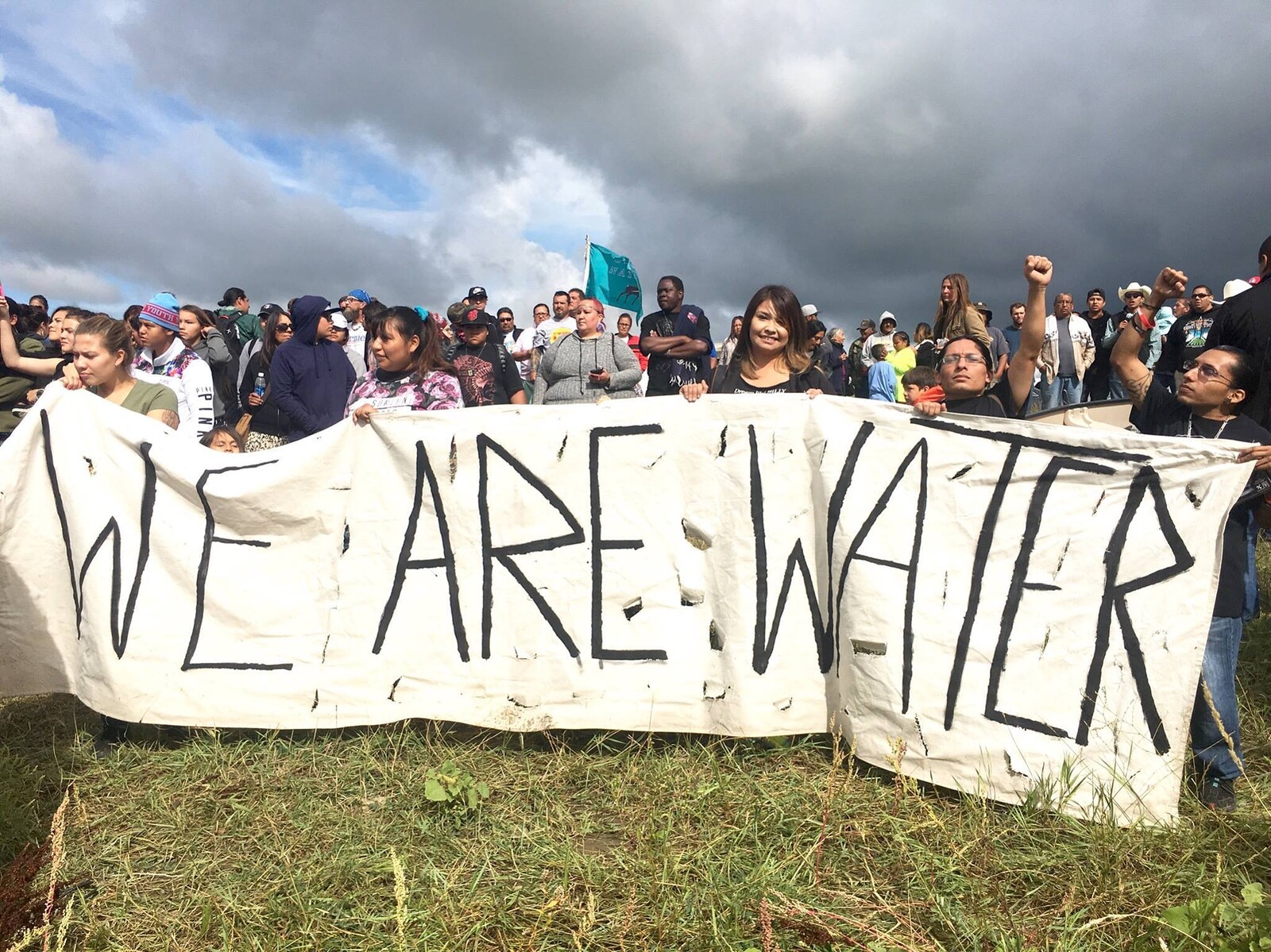

However, the denial of water ownership remains a contested political issue for Māori throughout the country. Māori have consistently disputed the colonial assumptions that water cannot be owned. In 2012, Māori from across the country presented a convincing case to the Waitangi Tribunal (a permanent commission of inquiry tasked with hearing Māori claims of past and present Government breaches of the Treaty of Waitangi). The Māori claimants’ case, sourced in the Treaty of Waitangi, argued that in 1840 Māori had full, undisturbed, and exclusive possession of all water. They claimed that the closest English cultural equivalent to express this Māori customary authority is “ownership.” And the Tribunal agreed: “Māori have little choice but to claim English-style property rights today as the only realistic way to protect their customary rights and relationships with their [treasures].”29 The claimants introduced a twelve point “indicia of ownership” framework for establishing customary proof of ownership:

1. The water resource has been relied upon as a source of food;

2. The water resource has been relied upon as a source of textiles or other materials;

3. The water resource has been relied upon for travel or trade;

4. The water resource has been used in the rituals central to the spiritual life of the hapū (sub-tribe);

5. The water resource has a mauri (life force);

6. The water resource is celebrated or referred to in waiata (songs);

7. The water resource is celebrated or referred to in whakatauki (proverbs);

8. The people have identified taniwha (water spirit/monster) as residing in the water resource;

9. The people have exercised kaitiakitanga (guardianship) over the water resource;

10. The people have exercised mana (authority) or rangatiratanga (sovereignty) over the water resource;

11. Whakapapa (genealogy) identifies a cosmological connection with the water resource; and

12. There is a continuing recognised claim to land or territory in which the resource is situated, and title has been maintained to “some, if not all, of the land on (or below) which the water resource sits.”30

Despite this case, the Government has remained resolute that no one owns water.

While many countries are seeking to commence reconciliation with Indigenous peoples, the recognition of Indigenous laws, rights, interests, values, and practices is often superficial.31 New governance arrangements in New Zealand begin to unsettle this broad global trend. Those Māori tribal federations who have negotiated cultural redress have more than a representative seat at the management table. These legal and policy developments signal that the law can be used creatively to find redress in the quest for reconciliation (even when water ownership itself is avoided). Existing public access to and use of lakes and rivers have commonly been preserved along with the existing functions and powers of local authorities.

In doing so, they provide a more significant avenue for Māori to advance their interests and connection to water than that offered through the Resource Management Act. These settlements reassert Māori law as the legal foundation upon which to know, care for, and use natural resources. These settlement statutes are providing national recognition of and provision for Māori law in New Zealand’s modern state.32 This recognition of Māori law inherently recognizes the Māori worldview, including the personification of lands and waters. Many of these water bodies are now recognized in law as having familial relationships with Māori federations.33 They enable a revival of Māori ways of valuing, caring for, and using water to co-exist alongside colonial national practices.

Eddie Durie, “Will the Settlers Settle? Cultural Conciliation and Law,” Otago Law Review 8 (1996): 449–465.

Joe Williams, “Lex Aotearoa: An Heroic Attempt to Map the Māori Dimension in Modern New Zealand Law,” Waikato Law Review 21 (2013): 1–34.

Jessica Hutchings et al., “Enhancing Māori Agribusiness Through Kaitiakitanga Tools” Our Land and Water National Science Challenge, July 2017, ➝.

Jacinta Ruru, Paul Scott, and Duncan Webb, The New Zealand Legal System: Structures and Processes (LexisNexis, 2016).

Nicola Wheen, “A Natural Flow – A History of Water Law in New Zealand,” Otago Law Review 9, no. 1 (1997): 71–110.

See Baden Vertongen, “Customary title to waterways – Paki v Attorney-General (No 2),” Māori Law Review (September 2014): 1–8.

Māori Land Act 1993, No. 4 (NZ).

US Department of Health and Human Services, “Profile: American Indian/Alaska Native,” 2018, ➝. See also Carolyn A. Liebler, “Counting America’s First Peoples,” Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 677, no. 1 (2018): 180-190.

To view a copy of the Treaty of Waitangi, see Treaty of Waitangi Act 1975. For discussion, see Claudia Orange, The Treaty of Waitangi (Bridget Williams Books, 2011).

See repealed statutes such as New Zealand Settlements Act 1863, No. 8 (NZ) and Suppression of Rebellion Act 1863, No. 7 (NZ). See also the work of Richard Boast including The Native Land Court 1862-1887: A Historical Study, Cases and Commentary (Thomson Reuters, 2013); Robert J. Miller and Jacinta Ruru “An Indigenous Lens into Contemporary Law: The Doctrine of Discovery in the United States and New Zealand,” West Virginia Law Review 111 (2009).

See Nell Jessup Newton, ed., Cohen’s Handbook of Federal Indian Law (LexisNexis, 2017).

For general comparative work on the United States and New Zealand, see David Hackett Fischer, Fairness and Freedom: A History of Two Open Societies: New Zealand and the United States (Oxford University Press, 2012).

To better understand New Zealand’s constitutional system, see Matthew S.R. Palmer, “Constitutional Realism about Constitutional Protection: Indigenous Rights under a Judicialized and a Politicized Constitution” Dalhousie Law Journal 29 (2006): 1.

Resource Management Act 1991, No. 69 (NZ), section 6.

Ibid., section 7.

Ibid., section 8.

Jacinta Ruru, “Indigenous Restitution in Settling Water Claims: The Developing Cultural and Commercial Redress Opportunities in Aotearoa, New Zealand,” Pacific Rim Law & Policy Journal 22 (2013): 311–352. See also Jacinta Ruru, “Undefined and Unresolved: Exploring Indigenous Rights in New Zealand’s Freshwater Legal Regime,” Journal of Water Law 20 (2010): 236–242.

Michael Reilly et al., eds., Te Kōparapara: An Introduction to the Māori World (Auckland University Press, 2018). See also Nicola Wheen and Janine Haywood, eds., Treaty of Waitangi Settlements (Bridget Williams Books, 2012).

For further discussion about the use of the term “ownership” in this context, see section entitled “Justice.”

“New era in Lake Taupo Management,” Rotorua Daily Post, May 22, 2018, ➝.

Te Arawa Lakes Settlement Act 2006, section 9. Note “Crown” means New Zealand’s national Government.

Jacinta Ruru, “The flow of laws: the trans-jurisdictional laws of the longest river in Aotearoa, New Zealand” in Trans-jurisdictional Water Law and Governance, eds. Janice Gray, Cameron Holley, and Rosemary Rayfuse (Routledge, 2016), 175–191; Linda Te Aho, “Ngā Whakatunga WaiMāori: Freshwater Settlements” Treaty of Waitangi Settlements; Linda Te Aho, “Indigenous Challenges to Enhance Freshwater Governance and Management In New Zealand - The Waikato River Settlement,” Journal of Water Law 20 (2010): 285–292.

Waikato-Tainui Raupatu Claims (Waikato River) Settlement Act 2010, section 8(3).

The Nga Wai o Maniapoto (Waipa River) Act 2012, preamble(16)(f).

Te Awa Tupua (Whanganui River Claims Settlement) Act 2017, section 14(1).

Ibid., section 69(2).

Ibid., section 18(2). Linda Te Aho, “Legislation – Te Awa Tupua (Whanganui River Claims Settlement) Bill – the endless quest for justice,” Māori Law Review (May 2016).

“Hydroelectric dam affecting Whanganui River – locals,” Radio New Zealand, April 21, 2017.

Waitangi Tribunal, “The Stage 1 Report on the National Freshwater and Geothermal Resources Claim” (WAI 2358, 2012), 32.

Ibid.

Sue Jackson and Lisa Palmer, “Modernising Water: Articulating Custom in Water Governance in Australia and East Timor,” The International Indigenous Policy Journal 3, no. 3 (2012).

Carwyn Jones, New Treaty New Tradition. Reconciling New Zealand and Māori Law (UBC Press, 2016).

The Waikato River, for example, is recognized as a tribal ancestor, and the Whanganui River is recognized as having legal personhood.

Liquid Utility is a collaboration between e-flux Architecture and the Temple Hoyne Buell Center for the Study of American Architecture at Columbia University as part of their project “Power: Infrastructure in America.”