Depending on the direction you are coming from, you may need to walk or drive through a street with a confusion of names to get to the Vernacular Art-space Laboratory (VAL) in Iwaya, a community along the coast of mainland Lagos. Once known by one name, the street is on the verge of getting subsumed by another.

As we walk to VAL, its founder, Aderemi Adegbite, provides me with a bit of local history. He tells me that the new name, Iyaomolere, is sponsored by a church that he points out along our journey. I ask him what he would do if he was a member of the old family that once had its name attached to the street. He says he isn’t interested in things like that, but if it bothered him enough, he would have to depend on the media to fight the change.

This humility helps mask his popularity in the area. From one corner to the next, people call out to him and greet him. He could be the local politician, but he is not: he is its resident artist. And as anyone familiar with the city would tell you, that is not an easy position to occupy in any part of Lagos. It is an especially tricky position to occupy in a low-income area like Iwaya. But Adegbite appears to be at ease with his community—and with the rather irregular route leading to VAL.

You walk down the double-named untarred road and end up at a canal flowing with a viscous black liquid. Ordinarily it would take a few steps to get to the other side, but that’s only when it is dry. On the day I am visiting, we depend on a canoe manned by a young man—a boy, really—who expertly paddles until he gets us across. His vessel either sways gently or shakes perilously, depending on the comfort level of the passengers. The usual passengers who need to embark on this journey several times a day are skilled at staying still in the canoe, but it is an uneasy task for a newcomer.

Once you get to the other side, after handing the canoe captain a small payment, you walk past several huts. Doing this requires becoming a funambulist, as you try to balance on a succession of wood planks, rocks, and tires sticking out from the ground to avoid stepping on the marshy, muddy ground. The huts look temporary, but as Adegbite says, none of them were constructed months ago. Families have lived here for years.

Keep walking and you go past a neighborhood bar and an overhead tank where water can be fetched via a tap. A woman stands under the tap, waiting for the pail on her head to fill. Moments later you arrive on an expanse of land, a clearing of sorts, just before the vast body of water over which the popular Third Mainland Bridge stands. Adegbite says this expanse used to be a sugarcane farm.

Crossing over the expanse are power lines, which some time ago the government insisted the community living in the area stop building underneath. Some sort of agreement was reached, but the community hasn’t complied with it for years. A few buildings remain under the lines. Such is the neglect of this area, that the flouting of an agreement with the government has yet to be addressed. But it is easy to see why. How often will inspecting teams from the government be motivated enough to take the trip over the rough terrain necessary to reach the community?

Adegbite doesn’t believe that it is difficult to access the community, however. After all, he says, when the Lagos state government wanted to demolish the “unwholesome structures on the waterfront,” its officers arrived via the lagoon.1 Nonetheless, the narratives surrounding the power lines fed an exhibition Adegbite staged about a decade ago.

As we continue walking, we see that a group of boys separated into teams has gathered to play football in the expanse of land not far from the area just under the power lines. This is recreation for the many kids in the community, which points to a different kind of recreation for the adults, some of whom sit under the shade provided by a few trees.

This place hardly seems like somewhere that might become the location for an art hub. Yet it is precisely here, in this community, that Adegbite bought the first few materials that would eventually lead to the building that today is the Vernacular Art-space Laboratory.

Aerial view of Vernacular Art-space Laboratory workstation. Photo courtesy VAL Lagos.

VAL WorkStation. Photo by author.

Around VAL WorkStation. Photo by author.

Aerial view of Vernacular Art-space Laboratory workstation. Photo courtesy VAL Lagos.

A few meters from the makeshift football field under the power lines stands a building unlike a lot of the buildings Adegbite and I have just walked past. It is more solid and looks like it can withstand heavy rainfall. This is the Vernacular Art-space Laboratory, a cavernous space with a zinc roof. As we approach, one side of the building has several grotesque heads are drawn in black. This work, by a graffiti artist named Nature, was part of “Postscripts,” a 2021 group exhibition commissioned by VAL. The number “20” is visible as a tribute to the events of October 20, 2020, the night the END SARS protests ended in violence—violence that is still denied by the government, even after some of its victims have shown their injuries.2

It was neither politics nor violence that led to the construction of the building, but it was close to a protest. Adegbite’s artistic practice was being met with resistance from people who didn’t like the idea of street photography. “People were just resistant to their photographs being made without being able to explain why,” he says. “And louts generally want you to pay them for photographs, even when it had no connection to them. They just want to make money off you.” Seeking respite, he came to this area in his own community to make images. It was during this time that he began to nurse the idea of creating a space.

“The idea came at the point in which I was transitioning from being a documentary photographer to a conceptual photographer,” he says. “All I needed was a studio; I didn’t need to be on the streets because I could bring in all of those ideas from there to one spot.”

As he tells it, what at first was meant to be a tiny space for one photographer’s dreams away from the bustle of the city, grew. This was mostly because of the one question Adegbite couldn’t initially answer: If his artist friends come to say hi and want to do some work, how would they all fit into such a small space? It became important to dream bigger. And thus, the idea for the Vernacular Art-space Laboratory was born. The first move was to acquire some land. He paid a family which claimed to be the owners of the land, and as he tells it, later paid them some more for reasons that prove hard to explain.

Eventually, he discovered that the land belonged to the government through the University of Lagos, which has its main campus not too far away from the area. Luckily, the school wasn’t too interested in developing the land. He could stay.

Today, the building stands on an area with grass barely rising above your ankles, overlooking its own portion of the Lagos waterfront. When it was first built, the area was overrun with heavy vegetation that needed to be cleared. To get things going, Adegbite organized a crowdfunding campaign, twice. The first time, he got $700 dollars, and then $800 dollars—sums that were impossible to build anything with.

“It barely got us to the level of the foundation,” he says.

Sometime later, the University of Lagos came to cut down some trees because they claimed people were smoking illegal substances under them. Unhappy about the situation and fearing he would lose the land, Adegbite gave up. “If the concept was to use the space for exhibition and to come up with ideas that will be presented to the community, why are we stressing ourselves to build a space? The space by itself won’t bring any ideas.”

Thus, a new idea was birthed. Adegbite and his friends would use non-spaces and alternative spaces rather a physical space. He describes the former as spaces that have yet to be used for art, while the latter involves utilizing plausible corners of the community for art. The pivot was impressive, but it was hardly the original idea of having a space for him and other artists to develop work, which hadn’t left Adegbite’s head. They might be able to get there at some point in the future, but for now, there were more urgent matters to attend to.

Untitled, performance by Abraham Oghobase at Iwaya Community Art Festival, ICAF Lagos 2017. Photo courtesy of VAL Lagos.

The Iwaya Community Art Festival (ICAF) was launched in 2016. Adegbite says he funded it entirely by himself and managed to get his friends from around the world to contribute their work. Without a space of their own, Adegbite and his team put photos wherever would be willing to host them. This sometimes meant being recriminated while putting things up; other times it meant working at night only for the works to be pulled down soon thereafter. Nonetheless, the festival held.

By the next year, greater ambition had crept into ICAF. It now featured more artists and was better structured. Some artists still balked at the idea of going to Lagos. But Adegbite thinks they had no reason to be scared: “Lagos is the safest place that I know in the whole world,” he says, laughing. “It’s just the terrible image that it has gotten over the years.”

This time, the festival received five artists from outside of the country for a residency. They were embedded with people in the community. Some people from the community gave a room to the incoming artists; others vacated their homes for them.

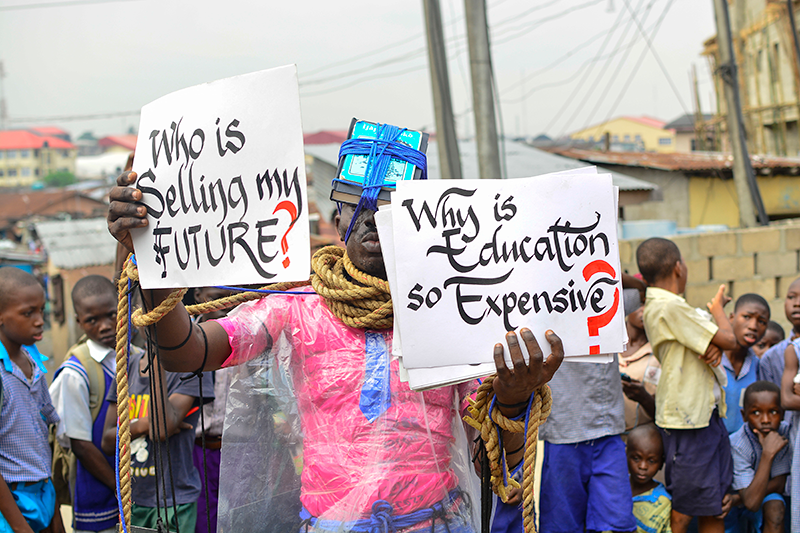

Funding came largely from Adegbite himself. He wanted to bring art to the people. But how well did the community take the art he brought? “Sometimes, they resisted it,” he says, noting that residents of the area aren’t typically well educated. “But they are not resisting what we are doing because they don’t like it. They are resisting it because they believe they should be getting something.”

What Adegbite is referring to is a common but understandable issue in certain low-income areas in Lagos, in which communities believe that they are being used by someone else to make money, and therefore coerce these people to pay the community before the project is concluded. It is unfair practice, but it is almost one of the unwritten laws of Lagos. A more charitable explanation is that this behavior is an overreaction to government’s negligence. While members of wealthy communities can do things themselves that the government has refused to do, those in poorer communities can’t. Instead, they rely on the belief that to get something tangible, they must take financial compensation from those viewed as creating value from the community.

Adegbite expresses his displeasure and frustration lucidly, but I get the sense that he can negotiate better than others. After all, he was born and raised in the area. Still, he is unhappy with the situation.

By the end of 2017, Adegbite had filed for and received official registration documents for VAL from the government, which allowed them to undertake projects. In the early weeks of the following year, Adegbite came across a call for proposals from the Prince Claus Fund targeted towards supporting “cultural expression for and with young people.” He proposed a project called Communal Re-Imagination, in which the lab would work with young people in his community for a year. The proposal got selected, and the lab received just over €20,000.3

The proposal mentioned that VAL would build a space for artists to show their work. So Adegbite went back to the space he previously abandoned and started building it again. Even though the grant was only for one year, he thought: “Why not build a space that these young artists can use and use and use even after the year?”

The building was erected in three months, although with considerably less ambition than the initial architectural design had specified, mostly due to budgetary limitations. By the end of the year, dozens of artists— dancers, visual artists, actors—graduated from VAL’s Communal Reimagination program. One of them, Olufela Omokeko, is still connected with the space.

Akudaaya performance by Yusuf Durodola. Photo by VAL Workstation.

For Keko, as Adegbite calls him, joining the program and becoming an artist was a kind of salvation. Working as an administration officer by day and studying to be a chartered accountant on the side, Omokeko stumbled a few times on one of the notoriously tricky national accounting (ICAN) exams and began to panic. “I was thinking, how will I survive?” he says. “This is the only path I know. What else can I do? How do I get back my life?”

The answers came to him on Facebook, where he found a call for applications to the Communal Re-Imagination program. He threw himself into it. “I resigned from my job and said, let me do this for one year and get back to the exams later.”

Through the project fund, Adegbite provided housing for Keko and fed him (and others) for the duration of the program. That year changed Keko’s life. He says that he emerged from the program with clarity: he took the ICAN exams again and passed them. But he hasn’t gone back to his former life. Instead, he chose to continue as an artist. Inspired by his experiences, his late mother, and his environment, he began as a performance artist, and has since taken up installation art.

Temporarily afflicted with accommodation issues after leaving VAL’s provisions, Keko was living with a friend somewhere else at the time of our exchange, but he was considering returning to Iwaya. “I was born and brought up here,” he told me. “There is a lot I can show to the world from this community.” He suggests that to produce the kind of work he makes, he needs to be sincere about his experience, which implies a proximity to his sources of inspiration.

Aganrandi, performance by Yusuf Durodola at Iwaya Community Art Festival, ICAF Lagos 2017. Photo courtesy of Aderemi Adegbite.

Keko is currently the space manager of the Vernacular Art Laboratory Foundation. The building was finally completed in 2019. Since then, it has held talks and exhibitions, but there have been challenges. A big one came the year it was finished, when the space was ransacked by hoodlums who destroyed many of the books that made up VAL’s library. In one interview with a journalist, Adegbite described what he saw: “[We] were disturbed by the number of books that were missing on the bookshelves. We searched every corner of the Workstation and saw some book covers in the dustbin bag… The contents of the books were taken away and the covers were dumped in the dustbin.”4

ICAF didn’t take place that year, a consequence of a personal revolt by Adegbite. Since the community was accusing him of making money from the festival and, presumably, not giving them what they believed was due to them, he wanted to demonstrate that it was possible for him to survive without it. A year later, he decided to bring it back, but then Covid-19 happened.

For poor communities like Iwaya, government-imposed lockdown added pressure on lean finances. Adegbite says he distributed some resources to people in the community. Fortunately, in an unexpected show of support, the Prince Claus Fund sent a message informing VAL that it would be receiving a sum of €5,000 of “relief funds,” which spurred the team to begin to dream of art once again.

In early 2021, “Postscripts” was staged at the lab. This time, the community was heavily invested in the outcome. People poured into the space to check out the event. Adegbite says this was probably because the pandemic had severely limited opportunities for outdoor recreation. “The place was filled,” he says. “I think people were tired of just sitting at home.”

The exhibition involved artists from neighboring communities, but rather than bring these artists into Iwaya, Adegbite took the exhibition there, to places like Bariga, another low-income area on the Lagos mainland. The exhibition’s breakout artist—the “star,” as Adegbite says—was Keko, whose work featured a bunch of peppers encased in nets hooked to boards suspended on VAL’s wall and ceiling.5

But there are still financial gaps. Moments before Adegbite told me of the publicity Keko gained after the exhibition, Keko mentioned that he didn’t have enough funds for a project he was preparing for the lab. I tell Adegbite what Keko said, and he responds with three words: “He will manage,” adding that without that exhibition from 2021, Keko would have had nothing to build on.

In that same exhibition from two years ago, Adegbite himself created a photography project, displaying passport photos of himself to show how he has been represented several times in the past by photographers. As he spoke, he seemed satisfied. “That was the biggest exhibition we have ever had here,” he says. “People came out! They were everywhere.”

In 2021, VAL also received a grant from the British Council for its second Communal Re-Imagination program.6 This time, the VAL team noted a surprise: one of the applications to the program was sent in by someone from a more affluent area around Iwaya. This was a bit surprising: it isn’t often the case that, in Lagos, people from very different social and wealth classes mix on the turf of the less privileged party. But Adegbite won’t be drawn into all that politics.

“The most important thing for me is that the structure we built is still standing,” he says as we walk back towards to the canoe that brought us into the community. “It is our highest achievement. Keko uses this space. Others, too, have used it and will use it for their work. So, I’ll always be grateful to the Prince Claus Fund. It gave us this building that took us from a non-space idea to a physical space.”

Several weeks after we walked down and up that twice-named street in Iwaya, Adegbite tells me via email that VAL has started a new project called the VAL Satellite Lab. The plan is to set up art labs in the four secondary schools located in his community, and the process has already started with one of the schools. “We hope the other schools give us space,” he says in the message.

Anyone who has visited the community would hope for the same outcome.

“Demolition starts at Makoko slum,” Vanguard, 16 July, 2023. See ➝.

Fisayo Soyombo, “PORTRAITS OF BLOOD (II): Names, Photos, Videos… How Lekki #EndSARS Protesters Were Massacred,” Foundation of Investigative Journalism, October 20, 2021. See ➝.

VAL had previously received a grant for €2,000 from the Dutch embassy, in 2017, to support the visit and participation of a Dutch artist in an ICAF artist-in-residence program.

Gregory Austin Nwakunor, “The agony of culture activist, Aderemi,” The Guardian, March 3, 2019. See ➝.

As part of the grant requirements, it collaborated with Site Gallery in the UK.

Interdependence is a collaboration between e-flux Architecture and OtherNetwork, a project by ifa (Institut für Auslandsbeziehungen) together with cookies.