If you want to evolve something, first you need a space so people can get together and exchange whatsoever they’re going to exchange.

— Ahmet Sisman in conversation with Tony Cokes.1

People don’t have to cooperate to work together. There is an assumption that to work collaboratively, collectively or together there is trust, but actually a lot of stuff gets done without that and it’s not a necessary part of collaborating. There are always a lot of tensions, competing desires, as well as reasons why people want to come together to do something.

—Sonia Boyce in conversation with Mikhail Karkis and Tessa Jackson.2

The ecology of the artworld in South Africa today relies on support from public and private institutions. Yet there is a deficiency of state and municipal funding for maintaining public art institutions as well as supporting exhibition programming, acquisitions, and publishing. This has led to privately-funded institutions and commercial galleries doing the work that public institutions should be carrying out. There is also an additional reliance on international (largely European) cultural institutions such as Goethe-Institut, Pro Helvetia, and The British Council to provide space, funding, and resources, often through the processes of online applications and open calls for proposals. The distribution of support from these organizations can reflect biases, be they aesthetic or political. And even when artists are supported by commercial galleries, their artistic output can be mediated by commercial interests and determined by international art trends.

Independent creative and cultural spaces are critical to creating grounds from which thoughts, ideas, concepts, and materials can be explored and cultivated. In South Africa, the question of space and ownership has been a point of contention since the 1913 Land Act and apartheid legacies that would later ensue. Land and resources were largely excluded from ownership by black South Africans. The absence of arts and cultural infrastructure for black artists during apartheid can be attributed to policies of separate development that created large economic disparities between black and white South Africans. Such asymmetries historically led creative acts of making and curating to be dominated by white practitioners, while non-profit organizations catered specifically to black artists was mainly led and dominated by liberal research organizations or religious institutions such as The Institute of Race Relations and the Evangelical Lutheran Church Art and Craft Centre Rorke’s Drift.

The self-determination and self-reliance espoused by the Black Consciousness Movement in the 1970s can be encapsulated in the isiXhosa expression “vuka uzenzele,” which roughly translates into “wake up and do it for yourself.” This principle of agency and control is embodied in the DIY approach in art that supports self-reliance and self-initiative. Instead of relying on institutions and professionals, individuals can do things on their own or do it with others. Two examples of artist-led organizations which espoused the sentiment of self-reliance and self-initiative are Federated Union of Black Artists (FUBA) and the Thupelo Workshops, both of which were located in Johannesburg.3 These initiatives were established in response to the gaps left by (white) institutional initiatives, which would often only support one or two annual exhibitions of black artists’ work—work most often produced in their homes or in underfunded studio spaces. As the late David Koloane stated:

At the time, FUBA was the only gallery trying to cater for black artists. The Institute of Race Relations used to have annual exhibitions for black artists but they were mostly group exhibitions where you’d find twenty-one artists in one show. If you sold anything there you’d jump for joy because the Institute of Race Relations was the only place people could go.4

Where FUBA was established to support black artists with representation, legal services, and spaces for education within the arts, the Thupelo Workshops sought to create space for local and international artists to work, exchange, engage, and learn from each other. Initiated in 1985 by Koloane and Bill Ainslie, they provided space for artists to create new forms of expression within a shared collaborative process with other artists. The Thupelo Workshops, together with the establishment of the Bag Factory Artist Studios in Fordsburg in 1991, cultivated a collaborative spirit of making and experimentation, often collectively working around resource limitations.

It is in light of these historical initiatives, as well as a number of other contemporary institutions such as FLAT Gallery, Atlantic House, joining room, Floating Reverie, sober and lonely, Keleketla! Library, Chimurenga, and Danger Gevaar Ingozi Studio that Covalence Studios was born as an attempt to provide support to experimental, research-oriented, and otherwise “outlying” practices. Its conceptualization began with an invitation to Bhavisha Panchia from the Goethe-Institut in London to participate in a three-day gathering to discuss, analyze, and map the obstacles, opportunities, and implications for decentralized artworld automation.5 Panchia invited her colleague Bettina Malcomess as a potential co-conspirator to explore how decentralized autonomous organizations (DAOs) could benefit artistic work and arts organizations.

The question of space and experimentation immediately came up for Panchia and Malcomess, bemoaning the crumbling infrastructure of art spaces and initiatives in South Africa. After the initial participatory gathering in London, the question of where and how experimental spaces for (digital) arts operate and function became the starting point for Panchia to explore the possibilities of collectively-driven spaces to support artists’ work. The artist studio was explored as a working model to think about the ways in which more experimental ideas and projects could be realized on a regular basis, through community coordination and cooperation.

The prospect to develop a prototype of an organization dedicated to more experimental, participatory practices was inviting as a potential addition to the creative arts landscape in Johannesburg. To develop a prototype is to test out a system, find its strengths and weaknesses, adapt it where necessary, and establish a preliminary model. Covalence Studios was a paper-prototype and an opportunity to (re)imagine how an organization could operate to support more loose, experimental, peer-to-peer projects and engagements. The model of the project turned to the artist studio, specifically the shared studio as a space that could engender exchange and the sharing of resources—both material and immaterial.

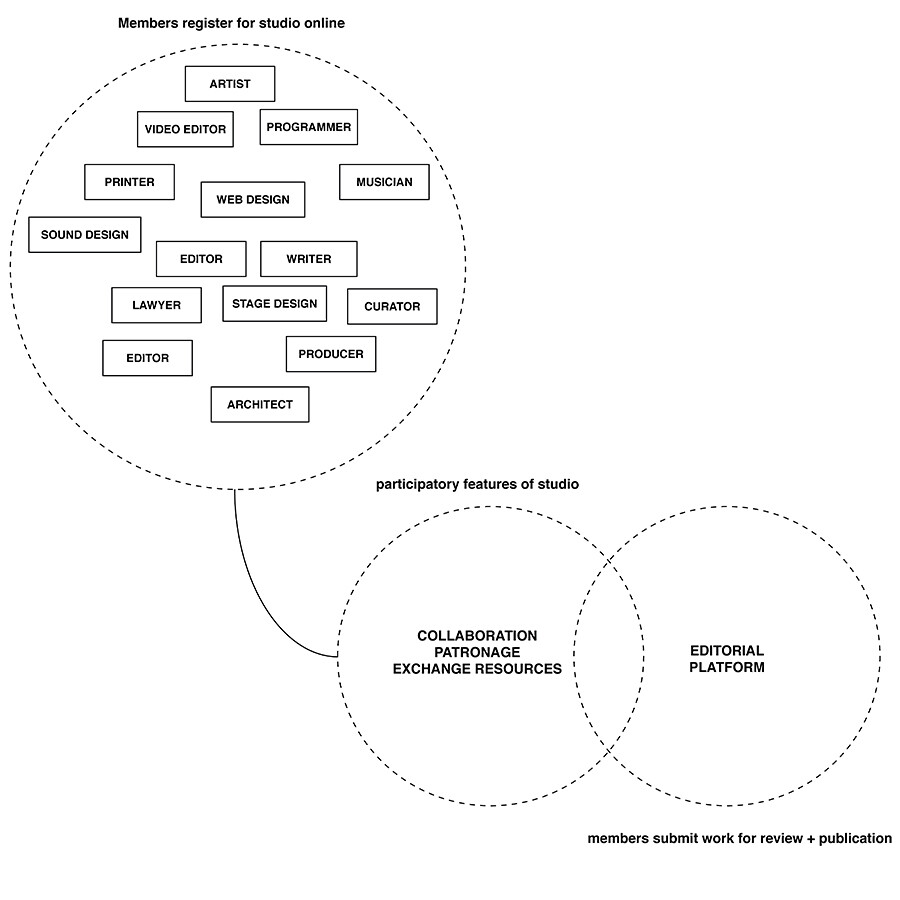

A diagram depicting the final model that Panchia, Whitaker and Cordeiro designed to reflect the studio’s structure and working relationship between participants in the studio. Image: Covalence Studios.

Having set up the initial concept, Panchia invited Carly Whitaker and Chad Cordeiro to help further research and formulate possible trajectories for the studio, with their respective artistic backgrounds and pursuits in mind. Considering how artists can work together with the digital medium to cultivate an artistic practice is at the heart of Whitaker’s research.6 Cordeiro began with an interest in expanding modes of collaborative, collective, and resource sharing practices beyond the studio setting.[Cordeiro works as an artist and printmaker with a history of collaborative and collective practice. The print medium—particularly in the context of South Africa—is historically rooted in self organization between artists, writers, curators, etc. Cordeiro co-founded Danger Gevaar Ingozi (DGI) Studio in 2016 with Nathaniel Sheppard and Sbongiseni Khulu with the aim to foster alternative forms of collective and collaborative practice, as well as to experiment with alternative economic structures between the print studio and the artist. DGI is an open studio and workshop for experimental collaborative practice with a focus on print-based media.] What brought us together was a keen interest in developing an equitable collaborative space and exploring different technologies as a conceptual framework for the studio.

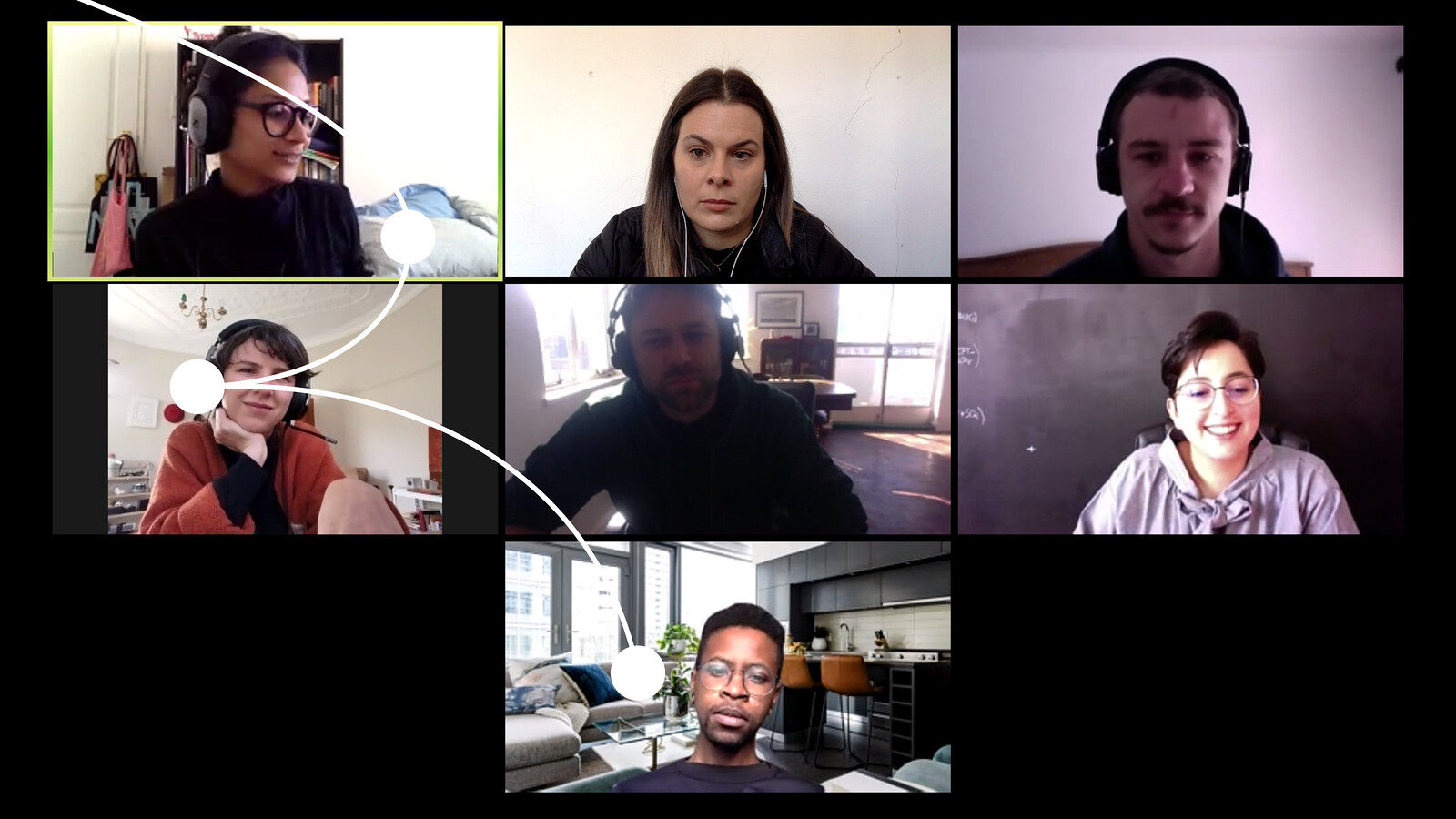

As part of developing the prototype and potential system, we convened a series of workshops and discussions with artists and creative practitioners who we identified as either having experience working with different technologies or having an established collaborative practice. We met with other artists based in Johannesburg such as Brooklyn J. Phakathi, Nathan Gates, Thulile Gamedze, Simon Gush, Naadira Patel, and Ilze Mari Wessels to explore the viability of such a studio platform.

Covalence Studios was envisaged as an online space that could cultivate and incentivize sharing and exchanging skills and resources amongst its members. It sought to create a platform that would evolve more integrated networks by providing creative practitioners with a central space where they can seek out connections for individual and collective projects. Imagined as an intermediary facilitating organization (online), Covalence Studios aimed to provide a remote or temporary setting for artists to initiate working together, and share skills or resources that they may have available and are willing to share with others. In this way, the platform was aimed at creating a space for artists to find the resources they may otherwise struggle to find. This could range from finding someone with installation experience, technical equipment, or skills such as editing, printing, or curating, which could be negotiated for and exchanged on the platform.

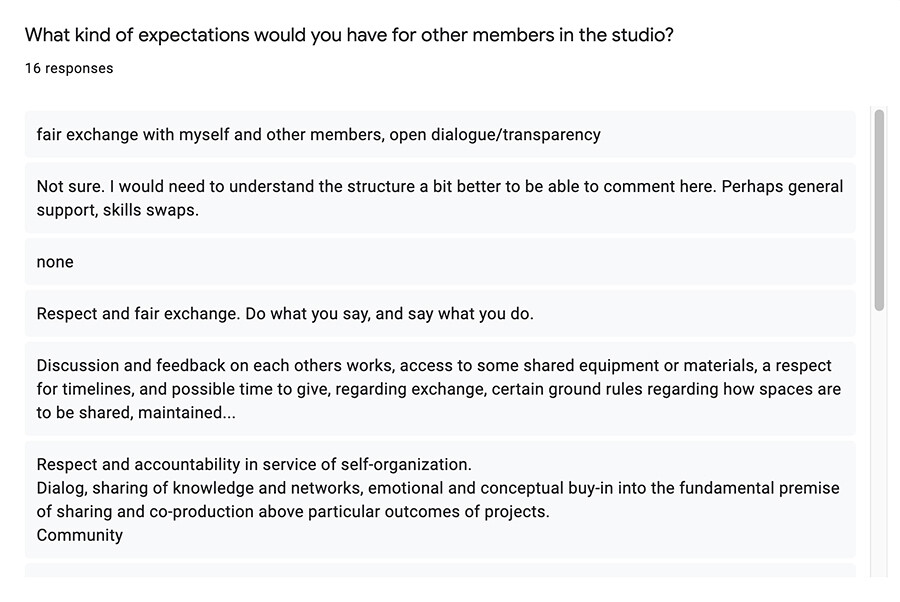

A screenshot of a question from the survey that was sent to several artists in Johannesburg. Image: Covalence Studios.

Covalence Studios was inspired by the nature of covalent bonds—bonds that occur when two atoms share electrons with each other. The valency of an element is a measure of its “combining capacity” and can be defined as the number of electrons that must be lost or gained by an atom to obtain a stable electron configuration. The studio was developed on the premise of a “combining capacity” amongst artists and creative practitioners who wish to extend, expand, and push their work into other domains. In short, the studio was imagined as a space for artists to test their toolkit out in different terrains and access a wide range of resources or skills within the city.

The studio was also oriented to tease out different modes of relationality and share equity amongst its members. We asked ourselves how a more equitable distribution of resources could differently shape the ways in which we work creatively? We began to think of how we as members of a shared studio space could (co)operate and produce work within an online context, seeking out questions such as: How can we think of trust and collaboration between artists and institutions, and between artists and other artists? What does it mean to work together creatively and intellectually within a society, so individuated and fragmented? Does working together mean you always need to cooperate? How can we begin to think of taking responsibility for the studio space together, its resources, for ourselves and for each other? How would systems of resource sharing, collective practice or even fair compensation for work/production look during and after a pandemic lock-down?

As a prototype of an organization in development and potential system, Covalence Studios was an exploratory undertaking attending to specific geopolitical conditions. In spite of the studio not being “built” online, its intention was to open up more equitable practices for artistic practice, and also attempt to create an environment that supports artists’ research enquiries. The studio was an attempt to extend the potential of the shared artist studio as a space for individual and collective thought and expression, exchange, collaboration, and innovation, and support interdisciplinary, experimental works and projects.

Both as a prototype and in its (unrealized) ideal state as a functioning system, Covalence Studios is a proposition to work across existing networks to support more lateral ways of sustaining creative practices. It is a vision for collective exchange and sharing of resources to allow for creative practice to be developed. This cross-pollination of skills and networks is intended to make available missed connections across the networks we currently occupy. Space for creative practitioners to organize themselves and their exchanges will always be needed.

The quote is taken from Ahmet Sisman in conversation with Tony Cokes from Mixing Plant, a project by Urbane Künste Ruhr for Ruhrtriennale in Essen, Germany, in 2019. The quote was featured in a poster and T-Shirt project by Karmaklubb in collaboration with Tony Cokes made in September 2019.

Sonia Boyce in conversation with Mikhail Karkis and Tessa Jackson discussing For you, only you. Institute of International Visual Arts, Scat–Sonia Boyce: Sound and Collaboration (London: Iniva, 2013), 15.

FUBA (Federated Union of Black Artists) was an art school and gallery co-founded by Sipho Sepamla and David Koloane in 1977. Due to financial difficulties, FUBA closed in 2000 after its art collection had been sold to an international buyer to cover outstanding debts.

David Koloane, “Our major issue was the labeling of black artists’ work,” by Gabi Ngcobo, Chad Cordeiro, Nathaniel Sheppard, Michelle Monareng and Matshelane Xhakaza, A Labour of Love (Frankfurt: Kerber, 2015), 52.

In February 2020, cultural practitioners and representatives of non-profit arts and technology organizations from Johannesburg, Hong Kong, Berlin, and Minsk gathered to participate in the Artworld DAO Think Tank – A 52hr Gathering, organized by Penny Rafferty and Ruth Carlow.

Whitaker started Floating Reverie, a digital residency program in 2014 with the intention of creating a space for artists to create and develop a practice in and through the digital medium, both online and offline. The residency program used digital space as a residency, studio space which becomes a site of repeated production and iteration of ideas and artistic practice. In 2020 Whitaker started an online art space, Blue Ocean which presents and displays digital born artwork. These multiple roles as one artist-curator-researcher-academic are not unique to her or her context, but speak more to the current sense of urgency to be able to play multiple roles and develop multiple skills.

Interdependence is a collaboration between e-flux Architecture and OtherNetwork, a project by ifa (Institut für Auslandsbeziehungen) together with cookies.