Sumayya Vally: It is such an honor to be in conversation with you both. I am speaking with you from Jeddah this morning, but I have a base in London and Johannesburg. Ra, you asked me if I am still in Joburg, and that left me with a sharp pang of homesickness, which it always does when someone asks. I am still partly in Joburg (I am wherever my work is), but Joburg is always in me. When I read Zen Marie’s essay “The Not-so-Quiet Violence of Bricks and Mortar” about Keleketla! and the work you do,1 I was reminded of Wally Serote’s poem “City Johannesburg” (1971), in which Serote laments leaving his homeplace for heartless Johannesburg. The line “I leave behind me, my love/My cosmic houses and people, my dongas and my ever whirling dust” really speaks of a longing for homeland. I could taste Joburg when I read this essay about your work, and it left me longing for my homeland. I was reminded of this “magic” time in Joburg, where everything was possible. We Joburgers were taking space-making into our own hands with an energy of activism and frustration, but also with memory, hope, nuance, and a deep reckoning with concerns around land. Having been around for over ten years, Keleketla! is an ancestor in that realm. We will get back to where it began in a moment, but let’s start with where you are now…

Rangoato Hlasane: We are currently located in Troyeville, which is on the east side of the city, close to Maboneng, and just next to the Jeppe police station. We are there as part of our placemaking and worldmaking practice, but also as part of our ethical exile from the Drill Hall.2 With respect to the issues that Zen writes about in that article, we left the Drill Hall in 2015 because it was not ethical for us to take care of both the building and the people who use it. At that time, we were the heart, the engine of that building; bringing life back to the building with programs such as our After School Programme (2008–2014), Skaftien (2011–present), and more. We felt that it was irresponsible of us to offer what we were and take care of the children from the inner city within such a neglected site.

We also acted as the building’s landlord for many years, which led us to be seen by some members of the community as gatekeepers. Our gatekeeping was always grounded in ethical principles, but was still seen by some as prohibitive to what they wanted to do with the site. But we always remained grounded. Thanks to our After School Programme, we had a pact with the children of the inner city. But issues of occupational health and safety were really the ethical grounds for us to have left the Drill Hall and go to where we are now, in Troyeville. Now that we have left, you can think of us as orbiting, expanding ourselves and continuing the placemaking tradition and history of Keleketla!

Thath’i Cover Okestra rehearsals, Drill Hall, Johannesburg (2015–2019). Photo © Kutlwano Moagi and Tjorven Bruyneel.

Malose Malahlela: We are time traveling in a sense that when we moved out, we were in limbo for close to a full year before we moved into this building by the Jeppe police station, the King Kong Jozi building. The King Kong Jozi building is on an industrial site, which required us to rethink the type of programming Keleketla! was doing, such as the After School Programme and the day-to-day library. These projects were rooted within the inner city, in the sense that kids connected us to the local schools, their parents, their teachers, their uncles, and so forth. Working with kids comes with a level of responsibility about how they’re catered to and cared for. We ended up hosting parent and teacher meetings at the site. Some children’s parents also offered to help us clean and maintain the site, some of whom we ended up employing to clean for us on a regular basis.

It was an emotional process to leave the Drill Hall in 2015, but it was also an organizational process. A number of our board members like Joseph Gaylard and Dorothee Kreutzfeldt were based there. When we moved to this new building, we effectively cut off a lot of our day-to-day engagement with the community. This site allowed us to reflect on the organization that we want to be and how we are going to move forward. At the Drill Hall, we were so easily accessible in so many ways that we became stretched. Caring for the community, for the kids, for our own practices, and for the building itself on top of everything brought us close to burnout.

Moving to our new space allowed us to retrace our steps. Ra and I originally met as students, and before founding Keleketla! were also in another collective. We have a vision of where we want to see Keleketla! going, but in order to really get there, we felt we had to carve out space for ourselves, become more boutique in a way, much smaller than we had been previously. We had to reshuffle our board and reflect on structural relationships, how we relate to and operate within the context of other institutions; your Swiss, your French, your British Council, etc. We had to think of how we play with power. We like to practice our own voice, our autonomy, our own ways of thinking, our own ideology.

When people enter into Keleketla’s world, they have to sacrifice a bit of who they are. But so do we. That’s the only way we can collaborate. We don’t collaborate for money; we collaborate based on a sense of what is worthwhile for us and where we want Keleketla! to go. What we want is to secure and sustain the Drill Hall, as well as the building where we are now. The only way to do this is to fight the City of Johannesburg. That takes infrastructure, and programming, but also understanding where are we in the larger scope of things.

SV: You’re touching on so many deeply resonant things. On the point of collaboration, we often have romantic notions attached to collaboration—especially in South Africa. Where we come from there is a legacy of having the power of a cause to rally around. We know from some of the older generation that there is also a bitterness attached to how forces played out, and only few are perceived as having benefited after a time of collective struggle, but still. There’s also something really interesting that you said about your model having to shift when you moved. There is an important intuition there that’s about collaboration with place. This is something consistent in Keleketla! through your operations at Drill Hall and where you are now: your work is an integral response, an action, and a catalyst. You actively work to dismantle, untangle, reform, and reconfigure something that’s already there.

This is something I also identify with, because if I think of my own practice in Johannesburg, it’s very much tied to what I mentioned before as this really magic time in Joburg, when there were so many things happening and when you could feel it was on the cusp of change. On the one hand, I was born into the “death” of Apartheid and our country’s democracy. As a child, I grew up during the era of Ubuntu in the Rainbow Nation; it was a time of incredible optimism. But then in my tertiary years, I graduate exactly on the cusp of the Fallist generation, a generation which I am a part of too. That was a time in which many expressed a desire and urgency to burn the existing structures and curriculum, reform them and call for real and radical change like rethinking curricula. There are so many overlapping forces from these moments in my life that that I can feel in Keleketla!

On the theme of collaboration and being made by a place, there’s something I think about sometimes. There are always all these ingredients—social forces, political forces, economic forces—but sometimes, and somehow, they all come together and make a form of practice, or an institutional structure. That’s something I find your organization really encapsulates. I don’t want to sound nostalgic, but it’s something that’s important to hold onto. I’m so glad to hear that you are moved and you’re feeling situated and rooted where you are. I’m feeling very old, but if I think about where Joburg is now, having visited last month, things are shifting. Can you take me back to what was happening, this magic time when you started in 2008?

Keleketla! Library, Radio, Stevenson Gallery Basement, Johannesburg, 2012.

RH: As Malose mentioned, we started as students, actually in 2003. At that time we were living in Joubert Park, three blocks away from the Drill Hall, in a student accommodation then known as the Mariston Hotel. A lot of us were students at the Technikon Witwatersrand (now University of Johannesburg) and other colleges around the city. Living in this building was incredible. It’s fifty-floors high with nineteen rooms on each floor, which held an average of about two students in each room. It was filled with lots of students from across Southern Africa, the majority of whom came to Joburg for its educational opportunities. We had that common purpose, but there were all these other kinds of other things that came up like moral difficulty and conscience. We formed a collective which we called innacitycommunity. It was rooted in hip-hop but quickly moved on to other things.

It quickly became a weekly session in each other’s rooms. My room, Malose’s room, just moving from room to room. Later, starting around 2006, we started moving out of our rooms and going into the ground floor sections of the building like the pool. The building has an interesting history. It used to be a five-star hotel, but evolved and became known for drug dealing and other “bad” things. Circa 2000 it started being converted into student accommodation. So as the building was ridding itself of its reputation, we were building this student-based collective.

Our weekly sessions went well beyond making and sharing music. In retrospect, out of both necessity and audacity, we basically created a parallel or alternate curriculum from the alienating syllabi and curricula we were given in our university studies. The collective became a parallel school for all of us. Outside of hip-hop, people brought things they were learning, like digital design, graphic design, how to fix computers, silk screen printing, flyer making, t-shirt printing, shooting and editing videos, etc. Basically, we taught each other how to make ourselves visible.

As we started moving towards not just graduating but also leaving this accommodation, reaching out into broader Johannesburg, we started bringing together and linking with other collectives. It’s through this process that we came to know about the Drill Hall, which was just a few blocks away. The magic for us was self-making when we were still students, thinking about how to take our alienating curriculum and make it relevant for us. Then, when we went to the Drill Hall in 2008 to start a library, that’s when everything came together.

MM: In the early 2000s the Drill Hall had a fire and was largely abandoned. In 2004, the Johannesburg Development Agency (JDA) renovated the site for R10 million. In 2007, as we were preparing to leave the Mariston Hotel, the Joubert Park Project (JPP), who was in charge of the Drill Hall site, was looking for tenants. So we made a proposal, and were accepted. But even before that, we hosted one of our hip-hop shows there with the Cascoland project, who was hosted at the site by the JPP. It was after this intervention that we submitted a proposal to the JPP to move into the Drill Hall. We formally occupied the site, taking over certain roles and responsibilities which the JPP couldn’t do on a day-to-day basis.

If we didn’t form this collective as students, we would have gotten lost when we moved out into the larger city and into what Johannesburg presented. Johannesburg is, like they say, the city of lights. But it’s easy to get drowned by these lights; to get all confused. This is always the case with youthful minds when they get to Johannesburg. It’s a very fast city. But we knew ourselves. We knew we wanted to gather all these youthful minds in the inner city, who were primarily people who moved from the north of South Africa to the city in the early 2000s. As students, we already imagined creating a library, a space dedicated to record collecting, to magazines and publishing, and putting on all these types of programs.

RH: When we started the library, the children of the neighborhood immediately began appreciating it. But they quickly started saying: “Mm, we want more than books. We want music, we want dance, we want theater, we want…” The children gave us a mandate! As the two-core engine of the student collective that began transforming and evolving into a library and a community space, Malose and I took that mandate. But we were honest in saying that we don’t have everything that these children are asking for. We had, however, throughout the previous years, linked with so many other people and collectives who all together might. We called them to come, told them what the children were asking, and offered them space at the Drill Hall in exchange.

Many of the rooms in the Drill Hall had been untouched since it burned down in the early 2000s and was renovated. They were dusty. We start cleaning these rooms and making them available to different collectives as studios for visual artists, music, etc. People moved their so-called bedroom studios to the Drill Hall. At the same time, they started responding to the mandate the children had given us. They opened themselves and the site to put on one-day shows or workshops in things like poster-making, theater-making, radio-making, music, and live choirs. That was really magical, understanding the place you are in and opening it up to broader Johannesburg. We found ourselves through this. We named it Keleketla! Library. “Keleketla” is a term from the Sepedi language, which is said in response to the way stories begin, “E ri le eng nonwane?” which in the Western world can be translated as “once upon a time.” Keleketla! is an active participation to the call of the storyteller, like:

E ri le eng nonwane?

Keleketla!

We met with Sumayya on this Zoom to speak…

Keleketla!

Sumayya has read some things, but now we are in this moment to understand each other further.

Keleketla!

…

We named ourselves Keleketla! in the sense that we want to be a library that conflates and colludes Western notions of the book as the supreme document and all these other multi-modal knowledge making practices not only in Southern Africa, but across the African continent and other parts of the world. Naming ourselves as a response to storytellers was a beautiful way of positioning ourselves as a responsive library; a library that listens and participates. It has never been a library that just takes content from the world; it itself produces and shares.

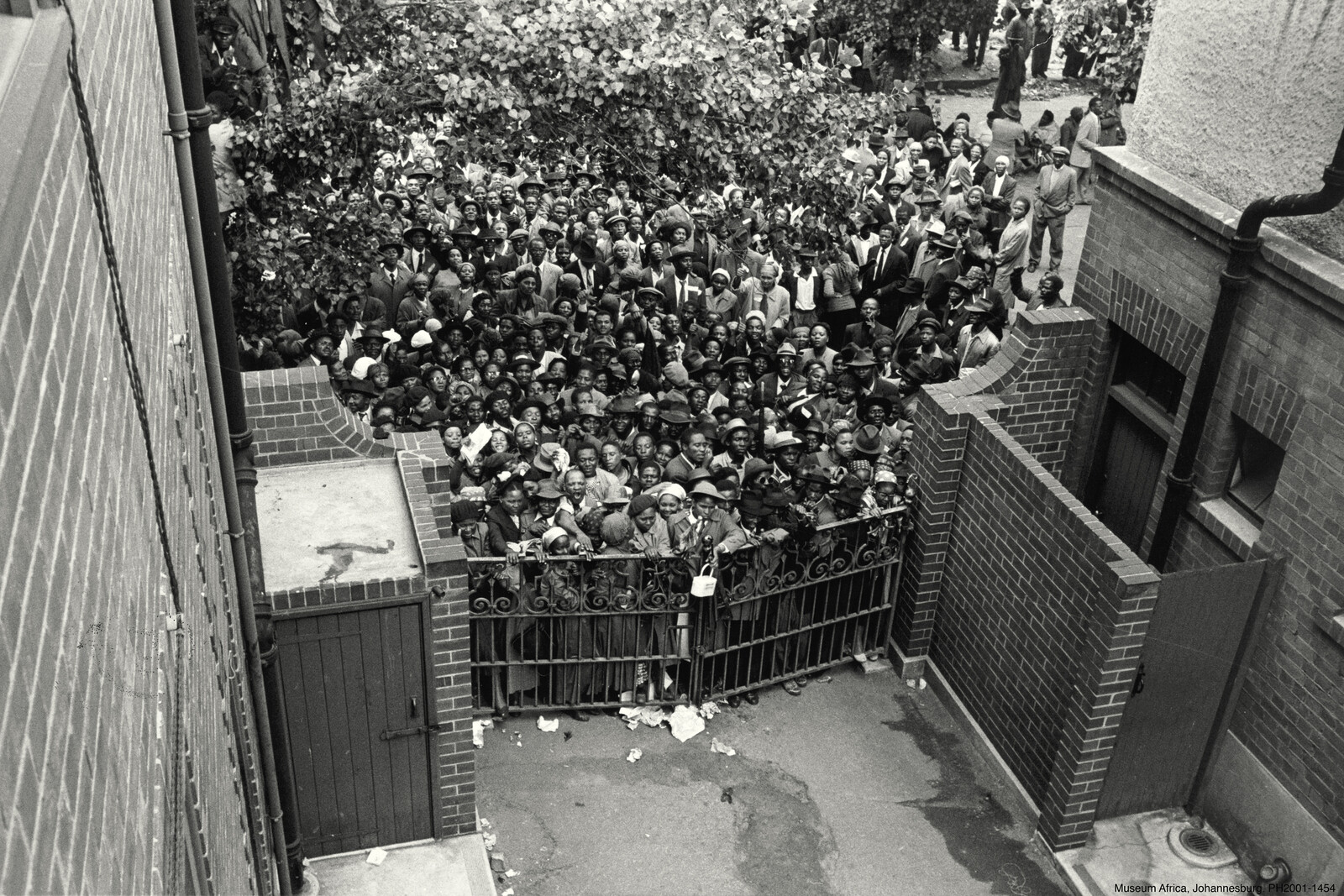

Photos of the Drill Hall in 1956 during the Treason Trial. Source: Museum Africa Archives.

Photos of the Drill Hall in 1956 during the Treason Trial. Source: Museum Africa Archives.

Photos of the Drill Hall in 1956 during the Treason Trial. Source: Museum Africa Archives.

Photos of the Drill Hall in 1956 during the Treason Trial. Source: Museum Africa Archives.

Photos of the Drill Hall in 1956 during the Treason Trial. Source: Museum Africa Archives.

MM: And then, right as were getting started, the JPP was awarded a National Lottery funding for the site that they applied to four years previously. At that time the JPP effectively left the Drill Hall and left us in charge of implementing the plan. The funding took effect from 2010, but we had already been implementing day-to-day programming since 2008. So within that period, in light of what had been happening, we worked with all the facilitators and users of the Drill Hall, to redraft their proposal, to make it more involved and more integrated with the community. We found some parts of their proposal to be problematic, such as their suggestion to bus learners into and out of the Drill Hall. But we also recognized and adapted the strong and relevant aspects of the JPP’s original proposal, which ended up becoming our 100 Metres Radius Project (2010-2012) and 56 Years to the Treason Trial (2010-2014).3

The history of the site itself, of the 1956 Treason Trial, became fertile ground to expand our programming with the After School Programme. Some of the publications that we printed about the heritage of the Drill Hall and the history of South Africa were meant to become integrated in local school curricula, which doesn’t speak much about the 1956 Treason Trial. The Rivonia Trial is more famous than the Treason Trial. The Treason Trial is when Mandela was brought to the Drill Hall with 155 other powerful contributors to the Freedom Charter from across South Africa—Govan Mbeki, Albertina Sisulu, all of them. But the Rivonia Trial is more famous. That trial led to the accused being imprisoned in Robben Island. But there were also fewer people at the Rivonia Trial than at the Treason Trial. We suspect that’s one of the reasons the city doesn’t grasp the significant heritage and history of the Drill Hall.

After it burned down and before it was renovated, the Drill Hall could have been demolished. Johannesburg’s City Council proposed doing just that in 2006. But the site doesn’t belong to the City of Johannesburg; it belongs to the national Department of Public Works. The city effectively leases the site from the national government. The fact that the city doesn’t own the site has led to a number of difficulties when addressing its past, its present, and its future. They can’t spend more money on it outside of that original 10 million that was dedicated to the 2004 renovation. Over the years, we have worked to contest the lease issue of the Drill Hall site, creating moments within different spheres of government to resolve the issue. As people who grew up with the inner city themselves,4 we understand the need to connect with the powers up there and bring them down—and vice versa.

Sumayya, when you were remembering Johannesburg at the time, Braamfontein was not what Braamfontein is. Newtown was beautiful for artists to reign and create so many things, but when the mall was introduced, when development started, most artists had to leave. They moved into the inner city. That’s how artists ended up at the Drill Hall.I remember the Lister building in 2011, which had a gallery on the top floor. That’s how we saw gentrification coming into the city; they mostly occupied the top floors because the ground floors were still dangerous. [laughs] We saw all these changes happen because we were there, we were in the inner city. Johannesburg was changing, but most places became unfavorable for most artists. The inner city became this hub, this very vibrant, this very tense Pan-African space full of artists, kids, and schools. I remember when we were working at the Drill Hall, our library, the city library was under renovation for so long! But of course, our library was not just for reading.

Keleketla! Library, Public Hearing, as part of the Centre for the Less Good Idea, Drill Hall, Johannesburg, April 18, 2018. Photo: Zivanai Matangi.

SV: When you described being in the student housing that you moved from room to room, I am again brought back to this idea of how you work with place, how place itself becomes a collaborator. There’s also something interesting about the history of the places that you find yourself in. It’s almost as if you’re collaborating directly with the fabric of history. There’s something really pertinent in your intuition that people remember the Rivonia Trial more than the 1956 Treason Trial because there were fewer people involved. That speaks to how we remember. Even if the subject matter is black, or of color, or indigenous, or coming from a different place, the forms that our memory are trapped within are still white supremacist and capitalist. That means it privileges the few, it privileges the written word, and so on.

I’m also really interested in how you think about the broader, the more invisible, the less touched, and how you work with Keleketla! as an active site of archive, which comes through in the production of sound, radio, and different forms of written media like magazines. There’s something in the systems that you work with that are in and of themselves a curriculum, or a pedagogy. There are the contents that you’re working with, but then there’s all the ways of being that you’re tapping into that are resonant with indigenous forms of knowledge; they’re aural and oral, they are performed, they relate to atmosphere, and so on. They also are hybrid in that they relate very much to Johannesburg, to what youth are doing in the city. There’s something about the project of the archive in a context like South Africa and the site itself, how you physically reconfigure history through being in there.

Your projects, for example Skaftien, and Stokvel, and even the word Keleketla! that you described so beautifully, are embedded in language. They are different ways to understand systems, and different ways to understand things. The two terms “Skaftien” and “Stokvel” are really interesting in how they hold power, knowledge, and structural logics. There’s knowledge locked in our language and in our ways of seeing the world that can then be translated into institutional logics or design forms; they can become something that manifests these practices. What is a “Skaftien”? What is a “Stokvel”?

RH: Stokvel, as many of us understand it here in Southern Africa as well as elsewhere including Jamaica, is a situation where people understand what needs to be done to resolve financial, economic, and socio-economic issues. The way it’s done, originally, is that a group of people come together and pool money over a period of time, whether it’s months or weeks, and give to a member for them to use. At play in Stoklvel are principles of trust, of communality, of understanding concrete economics on a very local level. However, in the month or the week in which one member receives the pooled money, that member creates something like an event in their home where people are welcomed; music is be played, issues are talked about, members of the scheme catch up with one another, food is shared, etc.

When we revisited this term in 2008, we were thinking about how to apply this practice to our space as artists, as cultural workers, where we protect ourselves and give ourselves? That’s the thing about being Black: you actually give yourself more than anything.5 We give ourselves to each other. So we first devised a Stokvel program that evolves first around visual art: curating a group of exhibitions where the work shown was donated to building up the media-making facilities of Keleketla! Then, Stokvel 2 invited people who still operated their studios in their own homes into the Drill Hall for a day to take part in the Allied Media Conference, where people in Detroit shared with us something similar that relates to them in the African-American context: a potluck, which also involves people coming together in placemaking practices.6

Stokvel then evolved into Skaftien when an artist, Kevin Clancy, came to do a residency at the Drill Hall. When hosting a residency program, we thought about concepts of hospitality, visitations, offerings. Building on the Stokvel model, Kevin introduced the idea of a group of people coming together to share a meal, which the public can pay a small fee to join. During this meal, guests are presented with cultural and music performances, as well as listen to proposals by community-based projects, who for lack of a better way pitch their ideas. Then, the people who paid to enter get to vote for a project to receive the funds collected from the gathering. Skaftien asks what do each of us come with? What do you bring to the table, to this environment? Are we just about taking, or are we about giving back?

Stokvel and Skaftien are rooted in the idea that we have to bring something to the table. Barter, which we have been working with since the beginning, always has to be a give and take. Outside of their traditional definitions, these two terms are rooted in what we’ve now come to understand as a way to keep our governments, our municipalities, our regional offices accountable. Instead of just doing photo opportunities or parading expensive cars around when it’s time to campaign for votes, what do they actually bring to the place?

MM: Skaftien is always about questioning how to situate and make these projects meaningful within our community. That’s why when we were invited to contribute to documenta 15, we conducted Skaftien #4 and #5 and brought some of our budget from Kassel back to Johannesburg. But we did these Skaftiens differently: as much as the previous Skaftiens were to support existing projects that are normally not taken by big funders in South Africa, we reframed and redirected these recent Skaftiens to try and secure the land, the program of the Drill Hall. Skaftien #4 took place earlier this year at the Drill Hall, for which we did the whole JOC (Joint Operations Committee) process; we paid for ambulances and all other types of things to make the event more “secure.”7 We even donated bins. Every time we do projects at the Drill Hall, we try to leave something behind. During the previous Skaftien, for example, which we did during Public Hearing in April 2018, we installed emergency plumbing.8

For Skaftien #5, however, we invited various Members of the Mayoral Committee (MMC) from Johannesburg to Kassel. We invited the mayor but her schedule was too complex. We invited the MMC of Economic Development (Nkululeko Mbndu) and the executive director of his office (Sabelo Chalufu). We also invited the MMC of Community Development (Ronald Harris) and his executive director (Vincent Campbell). The purpose of this Skaftien is to play soft power. Flying these political figures to Germany is meant to dislocate them from their office mandates, from their political tractions and restrictions and all these other things. We want to put them in a different context and whisper our intentions of what we want to achieve. By transporting them to Kassel was to maneuver differently. As a “third party” that’s not within government, we wanted to inspire a new mandate within these two mayoral committee offices towards the Drill Hall. One is to go to the Department of Public Works and deal with the land transfer (Community Development). Another is to secure partnerships and donors for the site’s rehabilitation, as well as its governance and continued programming (Economic Development).

Part of doing Skaftien #4 at the Drill Hall was already to strengthen relationships with these city offices. These office bearers were all very new in their offices. Today, actually, three of them are no longer in office due to a political change in the City of Johannesburg. They were in office for only ten months. The City of Johannesburg had a new mayor in what was a coalition government, but all that has changed. There is a now new mayor in place, and the city is no longer led by a coalition government.

Our negotiation with the City of Johannesburg has changed over time, with different mayors. All we can do is update new office-bearers on this long-term project on the importance of the Drill Hall and what we want to do with it. We are proposing for Keleketla! to work with the City of Johannesburg to do all that. Skaftien informs all these conversations across different departments, social spheres, and hierarchies.

SV: It’s an honor to know you. There is so much resonance between the way that you do things and my own ambitions and desires for Joburg and the world. Thank you for the work you do in our homeland, for “my cosmic houses and people, my dongas and my ever whirling dust.”

Zen Marie, “The Not-so-Quiet Violence of Bricks and Mortar,“ Planned Violence: Post/Colonial Urban Infrastructure, Literature and Culture (Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan, 2018).

The Drill Hall was the site of the 1956 Treason Trial, a trial in Johannesburg in which 156 people, including Lillian Ngoyi and Nelson Mandela, were arrested in a raid and accused of treason in South Africa in 1956.

Here we refer to our collective years of living and working in the inner city i.e. from 1999 to present to make a distinction from being born and raised in the inner city.

See Tendayi Sithole, ➝.

One of the studios, Slang Audio Records, stayed on at the Drill Hall after Stokvel 2 and continued to serve the music-making community.

The Joint Operations Committee (JOC) was established by the City of Johannesburg to ensure that all events held in Joburg are safe and that the event organisers comply with all by-laws and City regulations.

See Public Hearing, ➝.

Interdependence is a collaboration between e-flux Architecture and OtherNetwork, a project by ifa (Institut für Auslandsbeziehungen) together with cookies.